Miroslawiec

| Miroslawiec | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Poland | |

| Voivodeship : | West Pomerania | |

| Powiat : | Wałcz | |

| Gmina : | Gmina Mirosławiec | |

| Area : | 2.13 km² | |

| Geographic location : | 53 ° 21 ' N , 16 ° 5' E | |

| Height : | 120 m npm | |

| Residents : | ||

| Postal code : | 78-650 | |

| Telephone code : | (+48) 67 | |

| License plate : | ZWA | |

| Economy and Transport | ||

| Street : | DK 10 Lubieszyn ↔ Płońsk | |

| Ext. 177 Czaplinek ↔ Wieleń | ||

| Rail route : | Freight transport only: Złocieniec – Mierosławiec | |

| Next international airport : | Szczecin-Goleniów | |

| administration | ||

| Website : | www.miroslawiec.pl | |

Mirosławiec ( German : Märkisch Friedland ; Kashubian : Frédlądk ) is a town in the powiat Wałecki ( Deutsch Krone district ) of the Polish West Pomeranian Voivodeship . It is the headquarters of the urban and rural community of the same name .

Geographical location

Mirosławiec is located in Western Pomerania on the north bank of the small Körtnitzsee. In the north and south, the Draheimer and Kroner lake plateaus extend, which can be reached via a country road running through the village, each about 30 kilometers away. In addition, the state road 10 Stettin - Bydgoszcz ( Bromberg ) - Płońsk ( Plhnen ) runs through Mirosławiec (former German state road 104 Lübeck - Schneidemühl ). The city has an area of about 4,000 hectares.

Mirosławiec owns an air base and is the seat of the 12th air base of the Polish Air Force . In January 2008, a CASA C-295 military aircraft crashed near the air base with serious consequences .

history

Place names previously used are 1314 Niegen Friedland or Nuwe Vredeland , 1373 Fredelant , 1580 Frydlandek , 1754 Polish Friedland and 1783 Märkisch Friedland , New Polish Fredlądczyk . The place name contains the old German term Frede or Fried for a fortress (see e.g. Bergfried ) or for a fenced-in area, i.e. H. an area that is surrounded by a fence or protective wall. According to legend, settlers from Pomerania and Brandenburg are said to have founded the city. According to another assumption, the place name could indicate that settlers from Friedland in Central Markets were involved in the founding of the city .

The founding of Märkisch Friedland is related to the settlement operated by the Slavic princes and the Knights Templar in the 13th century , in which the Brandenburg margraves later also took part. The name Friedland is derived from "Vredeland" and was first mentioned in 1303 with the place name "Nova Vredeland". The town was founded by the Brandenburg margraves Waldemar, Otto, Konrad and Johann. They left the city to the Wedel family , and in 1314 the brothers Heinrich and Johann von Wedel, sons of Ludolf von Wedel , transferred Magdeburg law to Friedland . To protect the city, the von Wedel signed a defense treaty with the neighboring Kingdom of Poland in 1333, which was terminated in 1386 when Margrave Otto the Lazy sold the city and the surrounding area. The von Wedel resisted and sought the support of the Teutonic Order , which finally occupied Friedland in 1409. After the defeat of the order in the war against the Poles, they got the city back with the Second Peace of Thorne in 1466.

In 1543 the citizens of Friedland converted to Lutheranism and, unlike their southern neighbors, were able to successfully oppose the Counter-Reformation pursued by the Polish clergy. In 1593 the town of von den Wedel became the property of the von Blanckenburg family . This promoted the influx of Jews expelled from western Brandenburg , a measure that led to a significant increase in economic power. In later times the proportion of Jews in the population was up to 50 percent. A major fire in 1719 destroyed large parts of the city, including the manor palace and the church. In 1758 the catastrophe was repeated. The reconstruction that was then started was carried out by building mostly two-story houses.

With the first partition of Poland in 1772, the city came to the Prussian Kingdom and was officially given the addition of "Märkisch". With the Prussian administrative reform of 1815 Friedland came to the Deutsch Krone district in the West Prussian administrative district of Marienwerder. In 1836 the last offspring of the von Blanckenburg family died and Friedland became imperial direct, d. H. no longer privately owned city. In the first half of the 19th century there was a patrimonial court in Märkisch Friedland . In 1849 and 1852 Märkisch Friedland was hit by a cholera epidemic that had been rampant in the Deutsch Krone district since 1848 . After the city was once prosperous, it was considered impoverished by the middle of the 19th century. In 1900 it was connected to the Kallies – Falkenburg railway line . At that time, about 2,500 people lived in the city. Among them were only around three hundred Jews, as numerous Jews had been deported to Poland after the Prussian occupation by Frederick II .

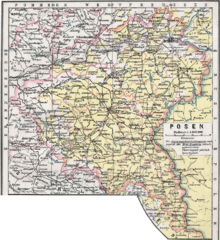

After the First World War , Friedland expanded with the influx of residents from the lost provinces of Posen and West Prussia, and the station district was created. The Prussian province Grenzmark Posen-West Prussia was formed in 1922 from the remnants of the surrendered provinces , to which Friedland now also belonged. In 1928 the city acquired the former Blanckenburg Castle and the property belonging to it. When the Grenzmark was dissolved again in 1938, Friedland came to Pomerania . The population had now grown to 2,700.

Towards the end of the Second World War , the Red Army captured the city in February 1945 , and a few weeks later it was placed under Polish administration. Polish authorities gave the city the Slavic name Mirosławiec . If the German residents did not flee, they were subsequently expelled .

Population numbers

- 1783: 1,305, 572 of them Jews, the rest all Protestant Germans

- 1804: 1,959, including 859 Jews

- 1839: 2,249, of which 1,479 were Protestants, 458 Jews and twelve Catholics

- 1854: 2,250, mostly Protestants, 499 of them Jews

- 1900: 2.233

- 1925: 2,060, mostly Protestant

Town twinning

sons and daughters of the town

- Josua Albu (born August 12, 1767 in Märkisch Friedland; † February 6, 1832 in Schwerin), rabbi

- Josef Liebermann (born June 14, 1783 in Märkisch Friedland; † January 29, 1860 in Berlin), industrialist

- Franz Wenzlaff (born September 29, 1810 in Märkisch Friedland, † February 3, 1888 in Berlin), educator, member of parliament and vice-president of the Mecklenburg parliamentary assembly, school director and professor at the Berlin building academy

- Heinrich von Friedberg (born January 27, 1813 in Märkisch Friedland; † June 2, 1895 in Berlin), lawyer and politician

- Joseph A. Stargardt (born June 17, 1822 in Märkisch Friedland, † April 30, 1885), publisher and bookseller

- Wilhelm Benoit (born August 12, 1826 in Märkisch Friedland; † March 3, 1914 in Karlsruhe), master builder and member of the Reichstag

- Julius Wolff (born March 21, 1836 in Märkisch Friedland; † February 18, 1902 in Berlin), surgeon

- Katharina Blümcke (born January 28, 1891 in Märkisch Friedland; † July 26, 1976 in Detmold), writer

- Hermann Fiebing (born November 17, 1901 in Märkisch Friedland; † October 5, 1960 in Stade), district administrator and district president

- Henry Makowski (born September 18, 1927 in Märkisch Friedland), naturalist and wildlife filmmaker

literature

- Friedrich Wilhelm Ferdinand Schmitt: History of the Deutsch Croner circle . Thorn: Lambeck, 1867, especially pp. 205–208 ( full text )

- Bernhard Lindenberg, History of the Israelite School in Märkisch-Friedland , Märkisch-Friedland, 1855

- S. 117, No. 13

- Dorothea Elisabeth Deeters: Jews in (Märkisch) Friedland. Aspects of their community life in Poland and Prussia , in: Michael Brocke , Margret Heitmann , Harald Lordick (eds.): On the history and culture of the Jews in East and West Prussia . Hildesheim: Olms, 2000, pp. 125-164

Web links

- Gunthard Stübs and Pomeranian Research Association: The town of Märkisch Friedland in the former Deutsch Krone district (2011)

Individual evidence

- ^ Friedrich Wilhelm Ferdinand Schmitt: History of the Deutsch Croner circle . Thorn: Lambeck, 1867, p. 205

- ^ Anton Friedrich Büsching , Complete Topography of the Mark Brandenburg , Berlin: Verlag der Buchhandlung der Realschule, 1775, p. 85.

- ^ FWF Schmitt: History of the Deutsch Croner Circle . Thorn: Lambeck, 1867, p. 205 ff.

- ^ WJC Starke: Contributions to the knowledge of the existing court system and the latest results of the administration of justice in the Prussian state . Part II: Justice and Administration Statistics , First Department: Prussia, Posen, Pomerania, Silesia . Berlin 1839, p. 163

- ↑ a b c Dr. Mecklenburg: What can the medical police do against cholera? Answered based on my own experience . Berlin 1854, pp. 22-23

- ↑ p. 117, No. 13.

- ^ A b Friedrich Wilhelm Ferdinand Schmitt: History of the Deutsch Croner circle . Thorn: Lambeck, 1867, p. 208

- ^ Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition, Volume 7, Leipzig and Vienna 1907, p. 111

- ↑ The Big Brockhaus . 15th edition, Volume 12, Leipzig 1932, p. 156.