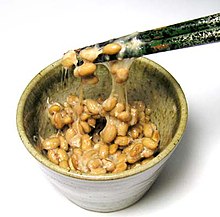

Natto

Nattō ( Japanese 納豆orな っ と う) is a traditional Japanese food made from soybeans . For production, the beans are boiled and then exposed to the bacterium Bacillus subtilis ssp. natto fermented . This creates a stringy slime around the beans and the food gets a strong smell. In the traditional way of preparation, the bacteria come from rice strawin which the beans are wrapped. In the modern production process, the beans are inoculated with cultures of the bacterium, so that the use of rice straw is not necessary. Nattō is served as a side dish to other dishes, used as an ingredient and consumed as a separate dish, seasoned with various ingredients. Some of the substances produced by fermentation have been shown to have a health-promoting effect.

Manufacturing

For the production of nattō, small, dried soybeans with a uniform shape and a smooth seed shell are preferred. Smaller beans have a larger surface area in relation to their mass. On the one hand, this shortens the cooking time and, on the other hand, it is assumed that the subsequent fermentation penetrates the inside of the beans more quickly. Due to the higher proportion of carbohydrates, the end product is also slightly sweeter. The beans are first thoroughly cleaned and soaked in water (usually overnight), then soft-boiled and dried for 20 minutes, or, in the case of industrial production, steamed for about 30 minutes at 121 ° C.

In the traditional production method, the cooked beans are then wrapped in rice straw. The bacterium Bacillus subtilis natto , which occurs on the straw , then causes a fermentation process . Since the bacterium could be isolated and made available as a starter culture , this procedure is no longer necessary today. The cooked beans are inoculated with the starter culture so that fermentation can begin even without straw. The fermentation process takes about a day at room temperature, but this time can be reduced to six to eight hours if the temperature is increased to 40 ° C to 43 ° C. The maximum temperature that should be reached during the fermentation process is 50 ° C, from 55 ° C the fermentation process stops and the bacteria die.

During fermentation, around 50% of the proteins in the beans are broken down, 20% of them into polypeptides , which are part of the polyglutamic acids and consist of glutamic acid units. A stringy, slimy substance forms on the surface of the beans, which is responsible for the typical aroma and taste of natto. In addition to polyglutamic acids, a very large amount of vitamin K 2 is formed during this process , with 880 µg per 100 g it is one of the foods with the highest proportions of this vitamin. It has been proven that the concentration of the vitamin increases 124 times during fermentation. Other important ingredients that result from the fermentation of natto, are vitamins of the B complex , nattokinase and dipicolinic , Levan , also is ammonia formed, which takes in too long fermentation too high a concentration and a negative effect on the taste. The total concentration of ammonia should not exceed 0.2%.

The aroma of the soybeans changes significantly during the production of natto. While the beans are being cooked, a “greenish” smell is created that is typical of soybeans. This smell turns into a sweeter note after about three hours of cooking. Both aromas disappear during fermentation. The final odor is influenced, among other things, by pyrazines , which are responsible for characteristic aromas that are perceived as burnt or roasted. In addition, various sulfur compounds are formed during the boiling of the beans, which have an effect on the smell after fermentation.

species

The Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science and Technology MEXT differentiates between a total of four different types of Nattō according to their production method:

- As Itohiki-Nattō (糸 引 き 納豆, German: sticky Nattō) steamed soybeans are called, which by adding Bacillus subtilis ssp. Ferment natto and thereby pull strings.

- Hikiwari-Nattō (挽 き わ り 納豆, German: Nattō made from broken beans) is a type of Itohiki-Nattō , which uses soybeans freed from the seed coat and split as a basic ingredient.

- Goto-Nattō (五 斗 納豆, German: 5 To -Nattō) is made by fermenting Nattō with Kōji and table salt one more time. The name is derived from the proportions of the ingredients: to 1 koku (= 10 t = 180 l) nattō, 5 t (= 90 l) kōji and 5 t salt are given and matured in barrels.

- Tera-Nattō (寺 納豆, German: Tempel-Nattō), Shiokara-Nattō (塩 辛納 豆, German: salty nattō), Hamanattō (浜 納豆) or especially in Kyōto also Daitokuji-Nattō (大 徳 寺 納豆, Nattō of Daitoku-ji ) are kōji-inoculated, salted soybeans that are dried.

Since there is no natto bacterium responsible for fermentation in the latter, and because the typical slimy substance does not form around the beans, only the first three types are usually counted as natto itself.

Another distinction is made according to the size of the beans used (before cooking):

- large: at least 7.9 mm in diameter

- medium: between 7.3 and 7.9 mm in diameter

- small: between 5.5 and 7.3 mm in diameter

- extra small: between 4.9 and 5.5 mm in diameter.

consumption

Nattō can either be eaten straight or over rice , but is also often used to prepare other dishes. When eating pure natto, other ingredients are usually added to flavor it. In a survey of Japanese natto buyers, 87.1% of those questioned stated that they used the sauces (soy sauce and mustard) included in the pack as a condiment. According to this survey, other ingredients frequently added to natto are spring onions (55.2%), soy sauce (35.0%) and eggs (25.2%). Other ingredients such as kimchi (fermented cabbage), katsuobushi (flakes of dried tuna), grated radish daikon , nori algae, roasted sesame seeds , mayonnaise , umeboshi (prunes) or tuna or squid cut into pieces are eaten with natto less often .

The preferences for dishes with natto differ somewhat when it comes to preparing them at home and eating them in a restaurant: 49.6% of those surveyed use natto sushi (natto maki) in domestic kitchens and 29.5% use it as an ingredient for miso soup , 23.6% for Chinese-style fried rice, 22.9% for egg dishes, 19.7% for udon or soba dishes and 17.8% for natto spaghetti . In gastronomy, natto sushi is of particular importance: 48.0% of those surveyed stated that they eat this dish when they eat natto dishes outside the home. Other dishes are mentioned much less often, the second most common octopus natto with 13.1%, followed by tuna natto with 11.0%. Other dishes that are prepared both in domestic kitchens and in gastronomy are, for example, Nattō- Karē , Nattō- Gyōza or Nattō- Tōfu .

Health effect

The health benefits of nattō have long been known in Japanese folk medicine. During the Bunroku War (1592), the warrior Kiyomasa Katō from Kumamoto gave his troops Nattō, which, in contrast to other Japanese warriors, are said to have suffered less from infectious diseases and digestive problems. The first written mention of the medicinal effect is dated to the year 1695: In the book Benchao Shijian ( Chinese本 朝 食 鑑 / 本 朝 食 鉴, Pinyin bĕncháo shíjiàn , W.-G. Pen chao shih chien , Japanese Honchō Shokkan , German: Ein Mirror of the foods of this dynasty), which was written by the Japanese Hitomi Hitsudai (人 見 必 大; around 1642–1701) in Chinese, the author writes about Natto that it is calming and helps against stomach problems, promotes a good appetite and detoxifies work. Furthermore, he was awarded effectiveness against cholera , typhus and dysentery .

An important part, is due to the medical effect of natto, is the serine proteases associated enzyme nattokinase . This shows a strong fibrinolytic (fibrin-splitting) effect. The abundant vitamin K 2 stimulates the formation of bones, and the formation of polyglutamic acids promotes the binding of calcium . Dipicolinic acid has an antibacterial effect against strains of Escherichia coli and Helicobacter pylori . These effects make Natto effective against thrombi , high blood pressure , osteoporosis and stomach ulcers .

Nattokinase is also able to break down deposits called amyloids , which may be associated with diseases such as Alzheimer's disease , transmissible spongiform encephalopathy and systemic amyloidosis . So far unidentified ingredients of the Nattō have a restrictive effect on the intercellular communication of certain cell types, which possibly inhibits the formation of cancer . In order to develop these effects in the human body, however, nattokinase would have to be ingested, whereby it is largely digested as protein.

story

etymology

The oldest known use of the term Nattō is written down in the script Shin Sarugakki and dates from 1068. The author Fujiwara no Akihira describes life in Japan in his time. He mentions Shiokara Nattō (塩 辛納 豆 'salty nattō' ). However, this may mean salty chunks of soy, which had been common in Japan since the 8th century. The term nattō is made up of two kanji : on the one hand納( on reading : na ), which means something like 'offer' or 'deliver', and on the other hand豆(on reading: to or tō ) with the meaning ' Bean '. The book Benchao Shijian / Honchō Shokkan by Hitomi Hitsudai from 1695 traces the term nattō back to nassho (納 所), which roughly means “temple kitchen” or literally “place of the [sacrifice]”.

Legends of origin up to the Edo period

There are different theories about the origin of the natto preparation. The most ancient statements go back that during or towards the end of the Yayoi period around 200 AD all the necessary conditions for the production of natto were already in place in Japan: bacteria, soybeans and rice straw. Bacteria related to the Natto bacillus existed 3 million years ago. Excavations in various places in Japan revealed burnt soybeans dated to the late Yayoi period or earlier. Rice cultivation in Japan began around 300 BC. BC to Kyushu in southern Japan and then spread throughout Japan. Nattō could have been created by chance at this time. However, there is no evidence or legends referring to this assumption. The assumption that natto was made from Chinese tan-shih (fermented, non-salty soy chunks) cannot be proven either. These were brought to Japan in 754 AD by the Buddhist priest Jianzhen .

Legends attribute the discovery of Nattō either to Shōtoku , a crown prince from the early 7th century, or to the samurai general Hachimantarō Yoshiie (1041–1108) from the Heian period . Shōtoku is said to have stayed in a village called Warado in Shiga Prefecture , which was famous for soybean cultivation. There he allegedly fed the remains of cooked soybeans to his horse and hung some of them wrapped in rice straw on a tree. The next day the beans had turned into natto, which the prince found very tasty. The method of preparation was adopted by the inhabitants of the village, and the name of the village was soon changed to Warazuto Mura (rice straw hull village).

The legends of Hachimantarō Yoshiie say that Nattō was discovered either in the Zenkunen War (from 1051) or the Gosannen War (from 1083). According to one version of the legend, Hachimantarō Yoshiie's soldiers were attacked while they were eating. They stowed the cooked soybeans that had not yet been eaten in sacks made of rice straw and tied them to the saddles of the horses. A few days later, the body heat of the horses had formed natto. In another version of the legend, Hachimantarō Yoshiie received Nattō from the residents of Iwadeyama as a thank you for helping in the Zenkunen War. During the Gosannen War, Hachimantarō Yoshiie is said to have given the surviving residents of the city of Sankanbu boiled soybeans, which he wrapped in rice straw for lack of other suitable vessels. After a few days, the recipients noticed that the soybeans had turned into natto. Since they liked the taste, they made soybeans this way themselves.

Already in the Heian period, Nattō was mainly known north of today's Tokyo , especially in the six northeastern prefectures of Fukushima , Miyagi , Iwate , Aomori , Akita and Yamagata . There were also areas in the mountains in the interior of Kyushu and in the province of Tamba north of Kyoto . During the Muromachi period (1333–1568), the use of soy sauce spread throughout Japan, replacing salt as a condiment for natto. In addition to natto, tofu also found its way into the kitchens of monks, samurai and the nobility during this time .

Nattō also owes its widespread use to a political control instrument: the sankin kōtai introduced in 1635 meant that the daimyō (princes of the feudal era of Japan) were obliged to spend part of the year in the capital, Edo . The associated exchange of cultures and customs meant that Natto was also known in more southern areas and in larger cities.

Meiji period until today

The opening of Japan to the western world at the beginning of the Meiji period (1868–1912) led to an upswing in various sciences in Japan, including microbiology , which came to Japan from Europe in the 1870s and 1880s. In 1894, Kikuji Yabe published the first scientific work on the fermentation of natto and thus laid the foundation for industrial natto production. He isolated a total of four microorganisms (three micrococci and one bacillus ) from Natto without naming or identifying them.

Another important contribution to the microbiological understanding of natto fermentation was made in 1905 by Shin Sawamura , who isolated two types of bacteria from natto and showed that simply inoculating cooked soybeans with these bacteria started fermentation. He named the two species Bacillus natto and Bacillus mesentericus . However, it turned out that Bacillus natto (later referred to as Bacillus subtilis natto ) alone is sufficient for fermentation.

However, the findings of science were not immediately implemented in commercial natto production. As a result, some well-known manufacturers who produced natto on a larger scale were confronted with greater problems in controlling temperature and oxygen content as the production volume increased. The consequences were initially production downtimes and then often bankruptcy. During this time, some scientists and their students began to sell the self-made natto as a university natto in order to receive additional income, for example from 1912 Shinsuke Muramatsu in Morioka or later Jun Hanzawa in Hokkaidō . Jun Hanzawa managed to improve and industrialize natto production with some innovations. In 1919 he developed pure bacterial cultures that could be used in industrial production as a starter for inoculating cooked soybeans, which made the use of rice straw superfluous. He also presented new, more hygienic Natto packaging made of pine wood, and he also designed an improved incubation room for production.

Further changes in the industrial manufacturing process followed in the 1970s. For one thing , the beans were cooked under high pressure , which reduced the cooking time to 20 to 30 minutes. On the other hand, packaging made of polystyrene and polyethylene was introduced in which the inoculated soybeans can ferment. During this time, some new natto products appeared on the market, for example natto with almonds , smoked natto with wheat bran , natto with kombu and natto based on barley or brown rice .

Perception in the western world

First mentions of Natto in western literature come from the early 17th century. The Jesuit- edited Japanese-Portuguese dictionary Vocabulario da lingoa de Iapam, com a declaraçáo em Portugues from 1603 is probably the earliest mention of some soybean-based foods - including Natto - in a European language. Nattō is described there as a type of food that is made by briefly boiling grains or seeds and then storing them in an incubation chamber. In addition to nattō, the book also mentions nattōjiru (miso soup with nattō).

In English, Nattō is first mentioned in the first edition of the Japanese-English dictionary by James Curtis Hepburn from 1867 and described as "a food made from soybeans"; the second edition of the dictionary from 1872 also contains this description unchanged. Nattō also appears for the first time in a dictionary in publications from France, the Dictionnaire japonais-français by Léon Pagés , published in 1868, is a translation of the Japanese-Portuguese dictionary from 1603. In 1895 a German-language summary of an English article by Kikuji Yabe about Nattō appeared in “Die agricultural experimental stations ”. There “a kind of vegetable cheese” is presented, in which “the strongly softened soybeans are stuck together by a tough, stringy substance”. Another German name for Nattō is used by Andreas spokesman von Bernegg in the book Tropische und subtropische Weltwirtschaftspflanzen, published in 1929 ; their history, culture and economic importance. Part II: Oil crops used; there the dish is called "Buddhist cheese".

A first mention of the production of natto on American soil comes from Hawaii in 1933 , the first known commercial natto production on the American mainland took place in Los Angeles and is dated to 1964. In 1984 there were a total of six natto manufacturers in the USA, three of them in Hawaii and one each in the states of Arkansas , California and Massachusetts . Nattō has been produced in Poland since 2015.

Economical meaning

The sale of Natto in Japan achieved a turnover of about 130.1 billion yen in 2005, for 2010 a turnover of about 131.0 billion yen (approx. 1.2 billion euros, as of September 2010) is predicted. The most important producers of Nattō are (as of 2005, market share in percent in brackets):

- Takanofoods - 25.6% (タ カ ノ フ ー ズ 株式会社, Takanofūzu KK )

- Mizkan - 10.8% (株式会社 ミ ツ カ ン, KK Mitsukan )

- Azuma Shokuhin - 9.1% (あ づ ま 食品 株式会社, Azuma Shokuhin KK )

- Kume Quality Products - 7.0% (く め ・ ク オ リ テ ィ ・ プ ロ ダ ク ツ 株式会社, Kume Kuoriti Purodakutsu KK )

- Asahimatsu Shokuhin - 5.3% (旭 松 食品 株式会社, Asahimatsu Shokuhin KK )

- Yamada Foods - 4.5% (株式会社 ヤ マ ダ フ ー ズ, KK Yamada Fūzu )

- Marukin Shokuhin - 4.8% (マ ル キ ン 食品 株式会社, Marukin Shokuhin KK )

- Marumiya - 2.6% (株式会社 丸 美 屋, KK Marumiya ).

All other manufacturers have a total market share of 31.4%.

Although indigenous soybeans are considered to be best for natto, only a small part of the soybeans used for natto production are grown in Japan (2004: 3.8%). The most important countries from which soybeans specially grown for natto production are imported are the USA , Canada and China . In total, over 400 different types of soybeans are used for natto, even outside of Japan, varieties that are adapted to the needs of natto production are bred.

Similar foods

In addition to natto, there are a number of other comparable foods, especially with regard to the preservation through fermentation, which is widespread in the East Asian countries. In Japan, in addition to the actual Nattō, you can also find Hamanattō and the Kyōto version Daitokuji-Nattō , which are made by inoculating soybeans with Kōji ( Aspergillus flavus var. Oryzae ). The Indonesian tempeh , which is often compared to natto , is also mostly made from soybeans. Here a mold of the genus Rhizopus is responsible for the processes during fermentation. Both the Nigerian Daddawa , the Thai Thua nao or the Kinema from Nepal are produced by fermentation of legumes under the influence of a bacterium of the genus Bacillus . In contrast to nattō, these are used as a spice for soups and other dishes.

In Korea there is Cheong-guk-jang ( 청국장 ;淸 麴 醬) and in Indonesia , Malaysia Tauco , Tauchu , and in China Shuidouchi .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c d e Sue Azam-Ali, Mike Battcock: Natto . In: SS Deshpande et al .: Fermented grain legumes, seeds and nuts - A global perspective , FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin 142, Rome, 2000. ISBN 92-5-104444-9 . Pp. 75-77.

- ↑ KeShun Liu: Fermented Oriental Soyfood . In: Soybeans: Chemistry, Technology and Utilization . Springer Verlag, 1997, ISBN 978-0-8342-1299-2 , Chapter 5, pp. 218-296.

- ↑ a b c Kan Kiuchi, Sugio Watanabe: Industrialization of Japanese Natto . In: Keith Steinkraus (Ed.): Industrialization of Indigenous Fermented Foods, Revised and Expanded , CRC Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-203-02204-7 , pp. 193-273.

- ↑ Ing-Lung Shi, Jane-Yii Wu: Biosynthesis and Application of Poly (γ-glutamic acid) . In: Bernd Rehm (Ed.): Microbial Production of Biopolymers and Polymer Precursors: Applications and Perspectives . Horizon Scientific Press, Cambs UK 2009, ISBN 1-904455-36-0 , pp. 101-153.

- ↑ Yasuhide Yanagisawa, Hiroyuki Sumi: Natto Bacillus Contains a Large Amount of Water-Solube Vitamin K (Menaquinone-7) . In: Journal of Food and Biochemistry , Volume 29, Number 3, June 2005, pp. 267-277, doi : 10.1111 / j.1745-4514.2005.00016.x

- ↑ a b c d e f Yoshikatsu Murooka, Mitsuo Yamshita: Traditional healthful fermented products of Japan . In: Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology , Volume 35, 2008, pp. 791-798. doi : 10.1007 / s10295-008-0362-5

- ^ FG Priest, CR Harwood: Bacillus Species . In: Yiu H. Hui, George G. Khachatourians (eds.): Food Biotechnology: Microorganisms , Wiley-IEEE, 1995, ISBN 978-0-471-18570-3 , pp. 373-422.

- ↑ a b H. Sumi, H. Hamada, H. Tsushima, H. Mihara, H. Muraki: A novel fibrinolytic enzyme (nattokinase) in the vegetable cheese Natto; a typical and popular soybean food in the Japanese diet . In: Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences , Volume 43, Number 10, 1987, pp. 1110-1111, doi : 10.1007 / BF01956052

- ↑ Etsuko Sugawara et al .: Comparison of Compositions of Odor Components of Natto and Cooked Soybeans . In: Agric. Biol. Chem. , Vol. 49, 1985. pp. 311-317.

- ↑ Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology:五 訂 増 補 日本 食品 標準 成分 表(Standard List of Food Composition in Japan, 5th Revised and Expanded Edition), Chapter 4豆類( Legumes ) 2005.

- ^ Eiji Monden: Federation of Japan Natto Manufacturers' Cooperative Society . ( Memento of May 4, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 9.9 MB) Set of slides for the 2007 Midwest Specialty Grains Conference & Trade show. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- ↑ a b 納豆 に 関 す る 調査 - 調査 結果 報告 書( Memento from September 17, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.3 MB) Japan Natto Cooperative Society Foundation (Natto investigations - written report of the investigation results). Published July 2009, accessed September 4, 2010.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k William Shurtleff, Akiko Aoyagi: History of Natto and Its Relatives , online excerpt from an unpublished manuscript History of Soybeans and Soyfoods: 1100 BC to the 1980s , Soyinfo Center, 2007.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h William Shurtleff, Akiko Aoyagi: History of Miso, Soybean Jiang (China), Jang (Korea), and Tauco / Taotjo (Indonesia) (200 BC to 2009) (PDF; 7.2 MB ) , Soyinfo Center, 2009, ISBN 978-1-928914-22-8 . P. 71

- ↑ M. Fujita et al .: Purification and characterization of a strong fibrinolytic enzyme (nattokinase) in the vegetable cheese natto, a popular soybean fermented food in Japan . In: Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications , Volume 197, Number 3, December 1993. pp. 1340-1347. doi : 10.1006 / bbrc.1993.2624

- ↑ Akiko Okamoto, Hiroshi Hanagata, Yukio Kawamura, Fujiharu Yanagida: Anti-hypertensive substances in fermented soybean, natto . In: Plant Foods for Human Nutrition , Volume 47, Number 1, 1995, pp. 39-47, doi : 10.1007 / BF01088165

- ↑ Ruei-Lin Hsu et al .: Amyloid-Degrading Ability of Nattokinase from Bacillus subtilis Natto . In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry , Volume 57, Number 2, 2009, pp. 503-508, doi : 10.1021 / jf803072r

- ↑ C. Takahashi et al .: Possible anti-tumor-promoting activity of components in Japanese soybean fermented food, Natto: effect on gap junctional intercellular communication . In: Carcinogenesis , Volume 16, Number 3, 1995, pp. 471-476, doi : 10.1093 / carcin / 16.3.471

- ^ The agricultural experimental stations: Organ for scientific research in the field of agriculture , volumes 45–46. Quoted from: Google Books preview.

- ↑ natto.pl

- ↑ a b Mpac:納豆 の 市場 動向 (~ 2005 年) ( Memento from January 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (MPAC: Markttendenzen Nattō bis 2005). Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- ^ William Shurtleff, Akiko Aoyagi: Soy Nuggets (Shih or Chi, Douchi, Hamanatto) , online excerpt from an unpublished manuscript History of Soybeans and Soyfoods: 1100 BC to the 1980s , Soyinfo Center, 2007.

- ^ William Shurtleff, Akiko Aoyagi: History of Tempeh , online excerpt from an unpublished manuscript History of Soybeans and Soyfoods: 1100 BC to the 1980s , Soyinfo Center, 2007.

- ↑ J. David Owens, Nancy Allagheny, Gary Kipping, Jennifer M. Ames: Formation of Volatile Compounds During Bacillus subtilis Fermentation of Soya Beans . In: Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture , Volume 74, Number 1, 1997. doi : 10.1002 / (SICI) 1097-0010 (199705) 74: 1 <132 :: AID-JSFA779> 3.0.CO; 2-8