Nuu-chah-nulth

The Nuu-chah-nulth (proper name, emphasis on chah ), Nuučaan̓uł or Nootka (outdated foreign name) are South Wakash speaking Indians on the west coast of North America . Their residential areas are on the west coast of Vancouver Island and on Cape Flattery , the northwest corner of the US state of Washington . Over 12,500 people were registered either with Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada as members of the 15 Nuu-chah-nulth groups (over 10,000) or with the Bureau of Indian Affairs in October 2016in the USA, where the only Nuu-chah-nulth live are the Makah (approx. 2,500).

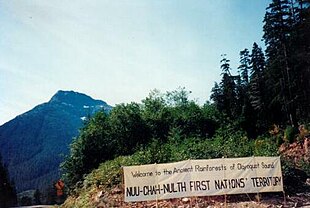

Since 1958, the bands , as these groups are called in Canada, joined forces and in 1978 they adopted the name Nuu-chah-nulth . When designating themselves , some groups also insist on the addition of First Nation or Tribe , although in Canada the designation First Nations has become established for the country's 615 recognized ethnic groups . Nuu-chah-nulth means "everything (people or land) along the mountains and the sea".

The northernmost bands of the Nuu-chah-nulth are the Kyuquot-Cheklesahht , whereby the Kyuquot live around the Kyuquot Sound , then to the south the Ehatteshaht and Nuchatlaht around the Esperanza Inlet and the Mowachaht-Muchalaht around the Nootka Sound . Today the bands of Hesquiaht , Ahousaht and Tla-o-qui-aht live around the Clayoquot Sound and Tofino . Ucluelet , Tseshaht , Toquaht , Uchucklesaht and Hupacasath live around Barkley Sound and Alberni Inlet . On the south side of Barkley Sound, around Bamfield and inland it is Huu-ay-aht , around Nitinat Lake the Ditidaht (Nitinat) , south of it the Pacheedaht . Then there are the Makah in Washington State.

Surname

The long common name Nootka was first given to the inhabitants of the coastline by the explorer James Cook . He had apparently got lost in the fog when some of the Nootka shouted: "nook-sitl"! ("You have to drive around the island!"). But Cook and his men believed it was the name of the island. Soon the term Nootka referred to all speakers of the Wakash language and included the Nuu-chah-nulth, Ditidaht (Nitinat) and Makah tribes. Up until the 20th century, the Nuu-chah-nulth themselves saw no need to adopt an overarching name. Some prefer the term aht-stems, after the final syllable that denotes all these stems, but Nuu-chah-nulth seems to prevail. Occasionally the term Nuu-chah-nulth-aht appears.

residential area

Their traditional residential area comprised mainly the entire west coast of the more than 32,000 km² large Vancouver Island , but extended over the Juan-de-Fuca-Strait to the Olympic Peninsula and into the area north of Seattle . The extreme points of this settlement area are the Brooks Peninsula in the north of Vancouver Island and Point no Point in the US state of Washington in the south, which are about 300 km apart. The area claimed by the tribes on Vancouver Island diverges. T. overlaps, largely from the more than 170 reservations transferred by the Canadian government in the 19th century. In addition, usually only one in three band members lives in their own reservation, in extreme cases not even one in ten. Many live in cities on Vancouver Island or in other British Columbia cities , especially Vancouver . In addition, the bands differ greatly in size. If more than 660 people live in the reservation among the Ahousaht , there are only 8 among the Toquaht. The population distribution among the approximately 2,800 reserve residents fluctuates accordingly. In addition, many non- indigenous people live in the traditional territories and also claim rights there. But this is less complicated, since the vast majority of the country (as Crown Land ) is in the hands of the government. However, the latest negotiations with the bands of the Maa nulth group may herald a radical change that will result in a reduction in the claimed tribal area but a tenfold increase in the size of the reserve. These would then, however, represent a private property that would also be alienable. The tribal areas, on the other hand, are inalienable.

The climate is characterized by strong, changing winds. Still, it's downright mild. In addition, the high mountains form a barrier that protects the area from the cold continental winds. On the other hand, they hold up the warm, moist winds from the sea, so that they dump most of the rain in this region - more than 250 cm annually, in some areas even well over 600 cm. Therefore, one of the largest temperate rainforest areas in the world is located here , as well as an enormous wealth of fish, especially salmon . The rainforest, the rugged river and lake areas and the relative seclusion of the area as well as the orientation towards the Pacific shape the culture of the Nuu-chah-nulth very strongly.

Nuu-chah-nulth groups

The original strength of the tribe is estimated at around 10,000 people. The Nuu-chah-nulth group in Canada today consists of 15 ethnic groups (in the USA the Makah (Kwih-dich-chuh-aht / Qʷidiččaʔa · tx̌) are added), of which 14 belong to the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council (only the pacheedaht is missing), a tribal council, and are jointly negotiating contracts with the Canadian government:

|

Culture

The culture of the Nuu-chah-nulth, which is counted to the northwest coast cultures , goes back at least 4500 years. After the decline of the last two centuries (see history), not only the number of the Nuu-chah-nulth has recovered, but also some parts of their culture. Certain components are indispensable for the survival of their culture. These include the natural environment in which cultural practices and works can arise and continue. The close interweaving with the (mythological) past and an emphasis on the ritual, in which all cultural expressions find their place, is still very pronounced. Much was not intended for everyone's eyes or was only brought out for certain events. Therefore, ritualized celebrations such as the potlatch are of great importance, especially since they underline the prominent importance of the traditional chiefs and their relatives, but also their obligations. The upbringing of the children was largely taken over by the grandparents, whose names that were not currently in use were passed on to the grandchildren - unless they inherited the names of the parents. Names could be changed at any time, but a festival had to be held at which the new name was announced. If someone with the same name died, the name had to be changed.

Even the first encounters with Europeans changed certain aspects of culture. Building a house makes it clear from the outside very early on which cultural and social issues were affected.

House and relatives

Typical of the houses, which were built for at least 2,000 years up to around 1890, is the mixture of solid and volatile structure. A series of sometimes huge stands - a construction that was only made possible by the huge trees of the rainforest - formed a basic structure that was used for a very long time, between which planks and boards allowed constant restructuring of the interior. This was closely related to the kinship structures that allowed individuals to move in with this or that group of their relatives. So around 1803 it was apparently no problem for Maquinna , the chief of the Mowachaht , that his son moved within his home to the British prisoner and slave John R. Jewitt , for whom the same chief had chosen a wife. This temporary placement within a house was of high symbolic value and was also incorporated into dances, singing and stories. At the same time, she emphasized the closeness to certain relatives.

Although the houses showed no external differences when Cook arrived in Nootka Bay on March 29, 1778, the chief's house was emphasized by a tall tree. Inside, too, only a few works of “artistic” character were to be seen, apart from the boxes, which were manufactured in an idiosyncratic but very practical process. On the other hand, the huge stands, which were carved but mostly covered, are striking. This was due to the fact that these stakes were not effective in themselves, but only in rituals performed by certain people. In addition to commercial goods, the crates are likely to have contained masks, the meaning of which was also only contextual, that is, they developed their magical and symbolic power within dances, stories and other rituals. In addition, the relationships within the groups were shown in this way.

First changes

The fur trade played an important role in the development of the Nuu-chah-nulth , into which they were drawn by Spanish and British traders as early as 1800. This changed the hunting methods. Sea otters were now primarily hunted, and the changed distribution of the yields created new leadership groups. In 1778, Cook had encountered houses with high gates, which in Yuquot were replaced by flat gates in 1800. It is unclear whether this is due to contact with the Kwakwaka'wakw on the north side of Vancouver Island . In any case, this type of house replaced the older one and existed until around 1880/90. In addition, the houses of the chiefs were now considerably larger than those of the other residential groups. Maquinna even had glass windows, Chief Wickaninnish stressed its prominent position by the largest possible stakes - with him a huge carved mouth served the largest stake even as input. This made the carved parts of the posts permanent and visible from the outside for the first time, while Maquinna solved the problem of the permanent display of his outstanding position in the fur trade by extremely frequent and complex potlatches .

The catastrophic decline in population due to diseases and wars began shortly after the first contact with Europeans, for example with the smallpox epidemic on the Pacific coast of North America from 1775, which was probably triggered by Spanish ships, and reached its extreme around 1940. At the same time, the residential family largely dissolved large potlatch houses were almost empty. Nevertheless, the traditional houses were built in Yuquot until around 1880.

New house types

For the first time in 1879, a family built a house with a gable roof and vertical instead of horizontal planking. In contrast to the past, the new houses were hardly inhabited, now differed greatly from one another, emphasized the status of the family permanently and externally, were not very variable and thus documented the radical change in society. Nevertheless, the houses were still being permanently rebuilt, many being newly built. Within 17 years all houses in Yuquot were rebuilt, some several times. The horizontal planks were replaced by vertical boards from industrial production. In the first decades of the 20th century, the closed row of houses along the coastline also dissolved into individual houses. The last house was built in 1924. Now totem poles were even erected standing individually in front of the houses. When chief Maquinna - the chiefs of the Mowachaht always bear this name because they come from a family who inherited the name - died in 1901, a large number of commemorative sculptures (whales, ravens, etc.) were erected in the open air.

The interior of the potlatch houses also changed. By around 1894, the inner partitions, which the families had somewhat sealed off from the other residents of the house, disappeared. Here, too, the ceremonial pieces were now open and visible and were no longer covered. The stakes no longer supported the house, but stood by themselves, mostly in a corner of the house.

Ritual exchange of food

Similar changes in symbols as in house building were evident in the all-important festive dishes, more precisely in their ritual exchanges. But this act differed in its frequency, because the other rituals were grand gestures, gigantic celebrations, which were used less often. The prisoner John R. Jewitt recorded exactly 140 formal invitations to a meal in his journals for the period from June 1803 to June 1805, 25 of them to a feast in another, 14 to a feast in the house he lived in. H. in that of the chief. Occasions for these festivals were often visits from strangers or neighboring tribes, or a great hunting success. Jewitt alone noted 117 visits from outside, almost always food being served - although he was not invited too often. The frequent, gift-like exchange of food in front of witnesses strengthened social relationships, as did common rituals and gifts. Gifts only became important when there was a change in society, such as at weddings, or when two of Maquinna's sons died.

Since the 1920s, giving away ceramic goods has replaced food on potlatches. Similar to how the potlatch houses were empty and their symbols were permanently public and separated from the actual festival, so the giving of food was shifted to the food containers.

hunt

In addition to the way of living, the way in which food is procured is particularly striking. The Nuu-chah-nulth specialized in whaling early on , probably as early as before the birth of Christ - in a form similar to that which the first European visitors encountered at the end of the 18th century. For this they used the only dugout - canoe , to harpoons with long lines and sealskin floats. The whale harpunist was held in high regard, and families passed on the magical and practical secrets necessary for a successful hunt. There was even a whale ritualist who, through appropriate ceremonial acts, drifted ashore whales that had died of natural causes. Many features of this whale complex point to ancient connections to the cultures of the Eskimos and Aleutians .

The catch of halibut and especially salmon also played an important role, especially for the provision of winter food. In general, no salt was used for preservation . Rather, the prey animals were preserved by drying them by exposing them to the strong sea wind and the sun. The distribution of the fishing rights or the distribution of the catch also took place in ritual form, in some groups by recognized experts, from whom a fair distribution was expected.

Bears and other game were occasionally part of the meat diet, but they played a subordinate role. Culturally dominant were whale and salmon fishing.

Collect

Also in the plant-based diet, which was mainly done by women, rituals and the allocation of special areas to certain individuals and families or houses played an important role. In the TI'aaya-as project, a research and teaching project, one tries today to collect, research and disseminate knowledge about plant nutrition through teaching. Roots, leaves and berries contributed just as much to the diet as the more spectacular hunt, but their cultural significance has declined sharply - and so far poorly explored.

The same applies to the collection of mussels and other small animals along the coasts and banks.

Canoes

In addition, the hunt is reflected more in “objects” than collecting, which are more easily accessible for collection, archiving and publication. This applies to the canoes , for example . The ocean-going boats were built for several purposes and therefore differed considerably from each other. While the seal-catching canoes, mostly manned by two men, were approx. 8 m long, commercial canoes could be well over 20 m long. There were also war canoes. The huge trees of the rainforest allowed such dimensions. The whaling boats were between 8 and 12 meters long. With sails (perhaps an adaptation of European technology around 1803) and oars driven, the boats were often found more than 40 nautical miles (around 65 km) off the coast, but also reached the Aleutian Islands . The canoes allowed a speed of 6 to 7 knots, which enabled a trip to Seattle within a day. This is the only way to explain the very extensive trade that existed long before Cook . At the same time, this trade, in which special boxes played an important role, promoted cultural exchange as far as Alaska and California .

The last canoe was probably built in 1945, but in 1991 a new one was created with completely new tasks, but using traditional technology. Today it is used by tourism as a vehicle for adventurous coastal trips. Canoeing has also been taught again for more than a decade, and traditional canoe trips have been used to introduce youngsters to their culture. The spectrum ranges from visiting neighboring locations to drug therapy applications.

Shamans and religious beliefs

Behind this need to achieve something through ritual acts was a worldview that was not easy to determine. The ancestors and the forces of the natural environment could use forces, e.g. B. healing powers confer. Conversely, one could influence the behavior of the animals through rituals and speech. The raven (as the bringer of fire), but also the wolf , the bear , the whale and the salmon played important roles. They applied rituals in which masks , dances, storytelling, martial performances of insensitivity to pain, food, gestures of generosity, etc. were central means of expression. The most significant ceremony was the shaman dance , a replica of the capture of an ancestor by supernatural beings who gave him supernatural gifts and set him free. The ceremony also served to determine each individual's place in the social hierarchy, and thereby their rights and responsibilities. The public performance ended with a potlatch , a strictly regulated property distribution ceremony. This distribution was so powerful that giving gifts to a man lower in the hierarchy has repeatedly led to his family being included in the group of traditional chiefs - with corresponding disputes. Therefore, a kind of master of ceremonies was trained who knew exactly what to do with this background.

Shamans, on the other hand, were people who perceived special powers in themselves, often in the form of dreams or visions. They did not hold any office, but were called, as it were, by internal voices. They were able to make contact with their ancestors or with the powers mentioned, be they animals, e.g. B. salmon or whales, be they powers. Women were shamans too.

If the exercises were successful, there was a vision ( ch'i h shitl ) in which animals such as otters , eagles, squirrels (a type of squirrel) and birds often played a role. They could bring a rattle or a song or some special medicine. Atleo, the great-great-grandfather of today's Ahousaht chief Sam, had a vision while hunting in Tofino Inlet . An otter turned into an eagle. The reward for healing was often a canoe or a tool.

Holy places and medicine

Many holy places are named for their function. So a cleaning water basin is a uusaqwulh h . A t'apsulh is a type of dive site. Both prayer pools and sacred caves are kept secret, while a dive site is known to all. An exercise in a holy place is called uusimich [ 7uusimch ]. The mother tongue should be used in prayer, for it is much more effective than English , according to the Nuu-chah-nulth . In order to attain spiritual power ( 7uusimch ) one goes to the 7uusaqulh , where a certain type of medicine ( tich'im ) is used. Each family has its own medicine, which has been inherited over many generations.

This may alder , Skunk Cabbage (skunk cabbage), but also wild lily (lily of the valley) yarrow , nettle , yellow lily , poplar - and spruce resin , coastal pine be, lichens and numerous other substances.

Tell

The narration was also very different from the narrative style of Europeans. Tradition distinguishes two groups of tales, the mythological, in which ravens, deer and gods play a role, and family legends. The former are of moral importance, explain phenomena, but can also be related by anyone who knows them. The family legends are completely different. They may only be told by members of the respective family. And they only belong to the higher-ranking families, the “nobility”. Very few of them have been translated and published to date.

Face paint and masks

Painting the face on festive occasions transforms the wearer of the painting by means of symbols and symbolic actions. These face paints interact vividly with the countless impressive masks. In 1778, for example, James Cook took with him various masks that were used for funeral rituals and that are now in London, Florence, Herrnhut and Cape Town. Cook saw masks of "enormous size" and "endless variety" which he first encountered, for example, in ceremonies performed on the approaching canoes. At the beginning of the 20th century, film recordings were made in which a shaman, masked and “dressed” as a raven, danced on a canoe while the rowers accompanied him rhythmically (today in the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria ).

It is known that the Makah painted their faces yellow and red during the campaign. Their chief Tatoosh met John Meares in 1788 with a face painted black. High-ranking men and women also wore nose rings made from seashells.

Headgear and braiding with wood fibers

The hats ( hinkiitsum ) of the Nuu-chah-nulth, which were already noticed by the first explorers, consisted of two layers, an inner and an outer. The inner layer consisted of the fibers of the wood of the red cedar , the giant tree of life , and was very soft, the outer layer of spruce and grass fibers (Phyllospacix torreyi). It formed a light background for the ornaments. The well-known depictions of animals were repeated in them, but also whaling events were symbolically brought to mind. Today motifs such as tribal names are added.

But not only hats were made from the fine wood fibers, but also baskets and even dresses. The necessary knowledge and skills were passed on from grandmothers and aunts. However, the compulsory schooling introduced by the Canadian government and the attempt to "integrate" the Nuu-chah-nulth (see below) have led to the fact that today the introspection of art within the family has been replaced by teaching. Despite all efforts, the traditional process, which ranges from owning and harvesting the wood and grass, to preparing the fibers, to exchanging and actually processing, can hardly be restored. As early as the 19th century, the much lighter, almost white bear grass (the white grass of Washington) made its way into the art of braiding, but was replaced in the 1970s and 80s by light green to cream-colored marsh grass, which was cheaper and easier to obtain. Today, easy-to-handle raffia is gaining ground.

The hats play a special role in that they were originally only worn by chiefs - hence their name Maquinna Hats . As early as 1900, private collectors such as Charles Newcombe played an important role in maintaining the manufacturing technique, and they occasionally ordered newly made hats in the traditional style from Nuu-chah-nulth women to fill in gaps in the collection. They achieved soaring prices as early as the 1960s and played an important role as symbols of traditional culture in the political disputes of the 1970s and 1980s. Their production is now taught in Port Alberni and Nanaimo . This also includes the traditional collection and preparation methods.

screen printing

Occasionally, Nuu-chah-nulth drew images of tattoos or mythical beings for ethnologists. As the name silkscreen print suggests, the colors were applied through a silk screen. This screen printing technique has found widespread use since the 1960s. If the artist does not actually do the printing himself, however, a lot depends on the technical skills of the printer. Titling and signature, possibly dating, plus the name, are applied to each copy by the artist. Most artists sign with their English name, some with traditional names. Screen prints are often done on special occasions, as a gift for the birth of a child, death, etc.

Carvings and paintings on rocks and trees

On the other hand, one of the arts that is no longer practiced is rock art , a distinction being made between pictographs (rock paintings) and petroglyphs (rock carvings, see petroglyphs ). The former were more likely to be found among the northern and middle Nuu-chah-nulth tribes and along protected waterways in the hinterland, the latter more likely to be found in the south on highly exposed stretches of coast (apart from two finds near Alberni , which may be from the time before the settlement by the Nuu -chah-nulth originate). McMillan's map shows around 20 sites on Vancouver Island, including some near the Makah. The pictographs cluster around Yuquot . Larger petroglyphs accumulate around Clo-oose in the Ditidaht area , and in the Makah area . Thunderbirds and whales dominate in both cases, and there are also anthropomorphic depictions of people, be it heads, female sexual organs or entire bodies. On Wedding skirt , a man reveals with a gun, this comes at Clo-oose a representation of a steam ship, apparently the Beaver , the first driving in the Pacific steamship. The function is not clear. Possibly they served as a reminder of important events, because they were extremely exposed, perhaps also as landmarks. From sources of the 19th century one can infer that at this time the approach to the processed stones triggered fears. Dating has hardly been carried out so far, especially since most of the dating methods are useless for these objects.

Arborglyphs (carvings on trees) and arborgraphs (paintings on trees) are rare . Trees processed in this way are culturally modified trees , i.e. trees on which traces of changes can be recognized that have a cultural background. These could have been used to build canoes, but also to extract fibers for clothing. Rituals can also have left their mark in this way.

language

Wakash is one of eleven Native language families in Canada, six of which are in British Columbia alone. Wakash is spoken by six tribes today and is divided into two branches (a northern and a southern), the largest representatives of which are the Kwakwaka'wakw and Haisla on one side, and the Nuu-chah-nulth on the other - with the northern ones and central Nuu-chah-nulth speak quite closely related dialects. The southern ones deviate more from it - especially the Ditidaht (Nitinaht) and the Makah , whose language, despite revitalization efforts, has almost died out. Therefore, the term Nootka , which is more linguistic, does not match Nuu-chah-nulth, a term that also includes political dimensions. There are 12 dialects in total. In 2001 only 505 people spoke Nootka, 205 of them regularly and only 15 exclusively.

Edward Sapir , director of the anthropological department of the Canadian National Museum in Ottawa , made numerous notes on the languages of the native peoples of North America in the years 1910-24, so that John Stonham was able to filter out around 150,000 words and enter them into a database. Part of it has flowed into a project on the Nuu-chah-nulth language.

There is now a dictionary of the language that contains around 5,000 main entries. With the help of this dictionary and further learning opportunities, it is hoped to be able to prevent the language from becoming extinct. Some of the bands are now making similar efforts , such as B. Ditidaht , who successfully teach their almost extinct language and only developed a writing system a few years ago. For some time there has also been a website on which the languages of the First Nations are presented.

Own media

Ha-shilth-sa (Interesting News) has existed since 1974 and is the official newspaper of the Nuu-chah-nulth nation - as it is explicitly stated, the deceased, the present and the not yet born. The sheet is printed in Port Alberni and appears every two weeks with a print run of around 3,500 copies, plus numerous e-mail subscriptions.

In 1999, the Ottawa government decided to license a radio station in Tofino , with the operator, PLM Broadcasting Ltd. , announced to broadcast 20 hours a week in Nuu-chah-nulth. But the station had to shut down in February 2002. Her successor was CHMZ-FM in November 2005.

In 2004 the Canadian government pledged $ 50,000 to fund the creation of a Nuu-chah-nulth Council website. The traditional chiefs also maintain a homepage called Uu-a-thluk (see web links).

history

Most of the Vancouver Island only became habitable at the end of the last Ice Age , but there are several, older , ice-free areas known as refugia . In the Port Eliza Cave, a cave on the north west coast, there were 16,000 to 18,000 year old remains of mammoths , mountain goats , as well as various types of pollen, which indicate vegetation with grass and trees. However, proof of an area that is habitable for humans is not sufficient to be able to prove a settlement route via the refugia from the Bering Strait southwards.

Early history

Excavations at Namu , on the mainland 150 km north of Vancouver Island, and at Lawn Point on Graham Island in the Haida-Gwaii area , show that the earliest known inhabitants as early as 8-9000 BC. Lived here. In the Bear Cove near Port Hardy in the north of Vancouver Island were found artifacts that relate to at about 6,000th Can be dated BC. They already point to fishing and hunting of marine mammals (dolphins, porpoises , sea lions ). The tiny blades that were also found there are striking.

With the end of the violent fluctuations in the coastline between 4000 and 3000 BC A culture of fishing and sedentarism developed with a growing number of settlements. Large mountains of mussels, known as shell middens , are typical here .

Excavations since the 1970s - at Yuquot , around Hesquiat Harbor and in western Barkley Sound , but also in the Makah area - have shown that this was already around 2300 BC. BC people lived. However, only a few artifacts have survived, as they consisted mainly of perishable materials. In the south of the Makah area, however, and at Nitinat Lake , some has been conserved by flooding. The oldest surviving sculpture (around 800 BC) comes from the Makah area, but it is uncertain since when the Makah lived there. The oldest piece that can be clearly assigned to the Nuu-chah-nulth tradition is 2000 years old: a bird's head made from whale bones. There were also combs made from pieces of antler from around AD 1000, some with wolf sculptures, others with human facial features. Antlers and bones, but also animal teeth, mica and shells also served as starting material for jewelry, even bird bones. But the number of finds is extremely small. More important was probably the body painting, which can be proven early, but naturally only rarely.

No later than 500 BC. Complex forms of society developed with elaborate rituals, artistic traditions and a highly developed spiritual life. Around 800 a certain population growth is assumed, because a number of newly created villages can be proven, e.g. B. T'akw'aa with the Toquaht in the western Barkley Sound or Hesquiat and Kupti in the upper Nootka Sound . In the former there were small stone whale figures, in Yuquot a thousand-year-old harpoon.

Maquinna, Wickaninnish and the first contacts with Europeans

The first visual contact with the explorers coming from Europe probably took place on August 9, 1774, when an undisclosed group of indigenous people saw the ship Santiago , led by the Spanish captain Juan José Pérez Hernández . But the Spaniards avoided all contact and never set foot on land. This fact may have saved the tribes of the region from the fate of other tribes who, through contact with the Santiago, brought in smallpox , which probably killed a third of the Indians on the west coast of the Pacific. But one now knew of rich men in floating houses.

James Cook

James Cook , from whom the misnomer Nootka comes, landed with two ships on Nootka Sound and Resolution Bay in 1778 , which marked the beginning of the first trading contact. The visitors to the five villages estimated the population from three to 700 to 1000, while the other two only had about 100 inhabitants. They also registered that there was fighting between these groups. The main trigger was the dispute over the trade monopoly with foreigners. The Mowachaht , the tribal group that settled around the Nootka Sound (no later than 1786), perhaps already organized the first trade of the Europeans and soon monopolized further sales into the hinterland. Everything the strangers asked for immediately became commodities, be it wood, provisions, even the right to sketch totem poles or collect shells on the beach. Even touching her property without consent aroused her anger.

The supremacy of the Mowachaht and the Spanish-British conflict (until approx. 1795)

It seems that this contact was viewed by the Mowachaht as an initial spark for the spread of a kind of claim to supremacy over the immediate neighbors. They now made a claim to leadership over all Nuu-chah-nulth who gathered annually in Yuquot. The opportunities for enrichment raised the prestige of the ruling class, the “nobility”, in the tribal group. Perhaps they did not succeed in occupying Yuquot until after Cook's visit. In any case, in 1788 the inhabitants of both sides of Yuquot Sound fought each other. Numerous prisoners of war became slaves, which is likely to have greatly enlarged the lowest of the three social groups.

But the demands of the indigenous people went much further. Apparently they had no qualms about taking everything they thought was beautiful or useful, as if it belonged to them anyway. The British, with their completely different concept of property, were helpless and extremely irritable. When two “thieves” were punished in 1786, those present quickly collected their goods and left the ship. It would hardly have been possible to explain to them that the Mowachaht had become British subjects through Cook's visit.

During the years 1778–90 / 95 the Spanish and British tried to enforce their claim to this stretch of coast (called Nootka Sound Controversy or Nootka Crisis ). In 1788, while traveling north , Esteban José Martínez learned that Russian fur traders were planning to set up a post in Nootka Sound. To forestall them, he sailed there in 1789 to create a post himself and claim the territory for Spain. However, when he arrived in Nootka Sound on May 5, 1789, there were two American ships and a British one that Martinez captured. A few days later he released the prisoners. On June 8th, Martinez captured North West America , which was sailing into the Sound, and on June 24th, formally and in front of the British and American eyes, claimed the northwest coast for Spain. The situation came to a head when the British ships Princess Royal and Argonaut arrived on July 2nd . Martinez also tried to enforce Spanish rule against the Americans, for which he escaped one ship that Fair American hijacked and another. However, a diplomatic conflict did not arise between Spain and the USA, but with Great Britain.

The local negotiations to settle the dispute took place with the generous host, the chief of the Mowachaht , Maquinna . They were based in Yuquot in Nootka Sound and were keen to do business with both nations. Their descendants now live on the Gold River, west of what is now Strathcona Provincial Park . Maquinna, was called Hyas Tyee , which probably means something like important chief . Since this title was also used for kings, this fits in with the kind of supremacy that Maquinna apparently sought. To this end, he used the annual meetings in Yuquot for important potlatches, implemented a targeted war policy and established marriage alliances. At the same time he managed to control the fur trade and the profits from it and to gain a great reputation. The fact that European weapons came into his hands with this gave his rule superior assertiveness - even if the use of loud and smoking guns may have had more psychological effects.

When the journals of the expedition were published in 1784, a real run on sea otter skins was triggered. Between 1785 and 1805, more than 50 merchant ships headed for the remote and difficult-to-reach region. At the same time, the conflicts became increasingly violent. There was a dispute about theft, the extradition of a deserter , in 1788 a ship's crew unceremoniously plundered a village in order to get fish and oil for the return journey. In the same year the visitors occupied land to establish a trading post, the following year a Spanish garrison was left behind. Eventually, Spain and Britain fought for supremacy, with Spanish captain Martinez hijacking four British ships and imprisoning the crews. They were interned in the Spanish colonies. On July 13th Callicum, a kind of co-ruler of Maquinna, possibly his brother, but also his opponent, was shot. Maquinna pulled away from Friendly Cove and fled to Clayoquot Sound , where he lived with Wickaninnish . It was only when the Europeans disappeared in October that he returned to Yuquot.

John Meares' activities were a key factor in worsening the conflict between Spain and Britain. He sailed for Meares Island (as it is called today) in 1788 and came into direct contact with the chief of the Tla-o-qui-aht , Wickaninnish , in June . The two agreed that the chief would provide furs and that the captain would return next year. Meares presented the chief with gifts, including pistols and muskets , for which he received 150 otter skins. But in 1789 the four ships that Meares had sent out as a member of a consortium were boarded by the Spanish captain Don Estevan José Martinez's fleet and his crews were brought to San Blas and Tepic . Meares brought a petition in the British House of Commons in May 1790 , encouraging the Prime Minister to drive the conflict to the brink of open war - and Meares knew how to put his role in the right light.

When the Spaniards returned with 75 soldiers in April 1790, some chiefs managed to ally themselves with them. Possibly they tried to shake off the completely unfamiliar "Maquinna system" again. A chief named Tla-pa-na-nootl was allowed to build his village near the Spanish bastion. Maquinna apparently fell ill during these months, and his tribe suffered from starvation.

In 1790 the policy of the Spaniards changed under the new viceroy. The leading head was now Bodega Quadra . He tried to win allies against the British and entertained and courted the chiefs, including Maquinna, whom he asked to return. Under the command of Francisco de Elizas , the Spaniards built a new fort. However, some of the crew members continued to insult, abuse and even kill the Nuu-chah-nulth.

John Meares, who came to London in April 1790, where the Spanish pirate firms were known in January, claimed to have set up a trading post before the Spaniards - on land that he had allegedly bought from Maquinna. In May the House of Commons issued an ultimatum to the Spanish government . Spain and France now equipped their fleets, but the French Revolution prevented the participation of Louis XVI. At the same time, the Netherlands supported Great Britain. Isolated Spain gave in on June 28, 1790 and signed the first Nootka Convention, also known as the Nootka Sound Convention . British and Spanish traders alike should now be allowed, but the issue of the fort on Nootka Sound could not be agreed upon, so the Spaniards just stayed. Alessandro Malaspina had also managed to win Maquinna as an ally.

Maquinna nevertheless profited from the return of the British in 1792. He invited both Quadra and Vancouver to Tahsis, where he held large parties. In addition, Maquinna offered the Spaniards to avenge the murder of one of their compatriots by foreign Indians. Hardly ever was the presence of Europeans so dense as it was in the years 1792–94, when 30 ships anchored in the Sound, ten (or twelve) alone at the same time in September 1792. Quadra demanded that the Spanish sphere of interest up to the Juan- de Fuca Street should be enough, Vancouver saw the border at Columbia . The Spaniards already set up a post with the southernmost Nuu-chah-nulth, the Makah at the north-western tip of today's Washington (Neah Bay). No agreement could be reached on the ownership of the Nootka Sound.

In February 1791, an American ship under the command of Robert Gray came onto the scene with the Columbia Rediviva from Boston . Gray had been to Nootka Sound two years earlier. This time, however, he got into an argument with the Tla-o-qui-aht over a deserter and unceremoniously imprisoned a brother of Chief Wickaninnish , but soon exchanged him. He returned in September looking for winter storage. On Meares Island he had his men build Fort Defiance . When they broke up their winter camp the following March, they set a fire in Opitsat, Wickaninnish's capital. A few days later, the Americans disappeared from the island forever.

The events in North America lost in importance in the face of the alliance between Spain and Great Britain against revolutionary France. On January 11th, Spain agreed to forego Nootka Sound. The Spaniards gave up their northernmost settlement in the Pacific on March 28, 1795 in accordance with the treaty. Now the Nuu-chah-nulth returned. The representative of Great Britain, Lieutenant Thomas Pearce, presented Maquinna with the British flag and asked him to hoist it whenever a ship appeared in the Sound. Both Spain and Great Britain did without a trading post. After only a year, the traditional houses had completely displaced the trading post.

Cultural changes and cultural misunderstandings

Still, a lot had changed. The area was sidelined due to the lack of sea otter skins, and hunting and trading moved further north. The Mowachaht now moved seasonally between the coast and inland to hunt fish and whales by the sea, and to get berries and meat in the hinterland. The lifestyle had changed radically within a few years. The annual meetings in Yuquot had acquired a different meaning, because it was now about the external representation and the consolidation of hierarchies, power and dependencies.

Conflicts with Europeans generally revolved around ownership, but there were other cultural misunderstandings. They revolved around the issue of cannibalism , the understanding of gifts, perhaps the role of female slaves. It seems that cannibalism, which Europeans have always met with the greatest reluctance and which has led them to the worst threats of violence, has been used again and again to discredit the respective neighbors. So it was hoped that the frightened traders would avoid the alleged cannibals. It would have been a means of damaging its reputation and redirecting trade contacts in its own interest. This could be based on the lessons learned from the first encounter with James Cook. The Indians apparently believed that the whites were cannibals and offered them body parts with the gesture of eating, which they rejected indignantly.

Further misunderstandings arose when the chiefs appeared on board after a potlatch in which they were extremely generous and expected the same from the captain and his officers. Their demands or their begging met with the greatest contempt and reluctance and led to serious insults. The question of whether female slaves were "offered" to foreign men and what goals were pursued by the chiefs remains completely unclear. After all, such anecdotes were a lure for the crews that should not be underestimated and were perhaps even rumored only to be able to recruit enough crews.

After all, the procedure of the trade, which was often very ceremonial and cumbersome, was a source of constant misunderstandings, and the white traders often felt provoked. Occasionally, chiefs were simply arrested to force the immediate surrender of all skins before payment was made.

From 1793–94 the Spaniards provided the “savages” in their area with food. Perhaps the tribes had focused so much on the highly profitable trade that whaling, which also took place in the summer, suffered as a result. As long as the barter brought in enough groceries, this was not a problem, but no ships came in the winter. Perhaps that is why the annual migration to Tahsis, further inland, began to hunt tuna and game, but also to collect berries and roots. The cultural change would then have been very early and very radical.

Maquinna may have died around 1795 - it is not certain whether the "younger" Maquinna is not the same person - who arguably remained the leader of a coalition of evolving tribes. It is also unclear whether these tribes were not house family groups before his time without common leadership.

Maquinna the Younger

The fur trade was now part of a triangular trade between Europe, China and Northwest America. Europeans drove to the Nootka Sound with metals and anything known to be coveted. There they took otter skins and beaver pelts on board and sold them in East Asia. With the enormous profits they acquired porcelain, silk and other Chinese goods that were in great demand in Europe. In the process, a trader's language was developed, which was called Chinook . It consisted of numerous Chinese, English, and Spanish words, but also words from the Chinook and Nuu-chah-nulth.

Nevertheless, the influence of the European visitors was initially noticeable mainly among the tribes that monopolized the fur trade, especially the Mowachaht. In 1805, for example, the members of the marriage shaht touched what was probably the first fair-skinned visitor, wrapped in strange clothes, with great astonishment (see Maquinna ).

Maquinna profited to a large extent from the trade for a long time and increased his reputation, which was expressed in the symbolically charged culture especially in large potlatches in which he once gave away 200 muskets. But the fact that the fur traders avoided the Nootka Sound after the act of violence of 1803 - which we know mainly from the records of the British John R. Jewitt - soon earned the chief much hostility from the other tribes, especially the neighboring " Kla-oo-quates ". They even attempted to kill him and his family between May 13 and May 16, 1804.

When a ship appeared in 1805, Maquinna was forced to take the high risk and visited the ship. But the captain imprisoned him in order to exchange him for the British captured in 1803. This act of hostage-taking appears to have ultimately destroyed the chief's reputation. The journals and description of imprisonment later published by one of the two, John R. Jewitt , no longer provide the, albeit distorted, picture of traditional society that Cook had encountered. When Camille de Roquefeuil arrived in Nootka Sound in 1817, the supremacy of the Mowachaht was apparently broken. Many tribes were at odds.

Nuukmis and the Tonquin (1811) - the end of domination

In 1810 the Pacific Fur Company was founded in New York . Half of the shares belonged to the American Fur Company John Jacob Astors , which provided the capital for the Pacific operations. To conduct the Pacific trade, two expeditions were sent, one overland and one around Cape Horn . In 1811, the crew of a fur-trading company ship established a post on the Pacific coast called the Astoria .

In June 1811 this Tonquin , who had sailed around Cape Horn, anchored in Clayoquot Sound to buy furs. But the chief of the Tla-o-qui-aht (from Echachist), Nuukmis, was indignant that he had been betrayed and hit the negotiator in the face with a rolled up skin. But the fur traders ignored this clear warning sign and stayed. A few days after this incident, canoes laden with skins approached and others followed. Nuukmis and his Wolf Clan were no longer interested in trading. When the captain, becoming suspicious, wanted to set sail, the Tla-o-qui-aht pulled knives from their bundles of fur and cut the crew down. However, some men managed to open the gun lockers and use the muskets to drive away the intruders. The few surviving sailors tried to leave the disabled ship and flee, but were also killed. The last survivor on the ship lured the Tla-o-qui-aht on board the next day, but then blew up the entire gunpowder supply . Around 150 Tla-o-qui-aht were killed. This loss of warriors was so great that the women supposedly had to dress up as warriors as soon as another tribe came near their area. After this event, the fur traders avoided the region for decades.

The Wickaninnish tribe, who were related by marriage to Maquinna and one of the winners in the fur trade, had thus been severely decimated. The trade in sea otter skins finally ended in 1825, at the same time the power of the two dominant tribes was apparently broken.

North West and Hudson's Bay Company

In 1821 the North West Company's fur traders and hunters association merged after years of disputes with the Hudson's Bay Company . It extended far into what is now US territory, an area similar to the states of Washington , Oregon , Idaho , Montana and Wyoming . This new company received the exclusive right to trade with the "natives" in 1838 and in 1843 established a trading post on the site of today's Victoria . It was secured by the border treaty between Canada and the USA of June 15, 1846, which struck Vancouver Island Canada. Canada left the entire island to the Company for ten years.

Under the leadership of George Simpson , the company changed its character and intervened more and more in regional conditions. In 1838 he applied for the right not only to trade with the indigenous peoples for his society, but also to set up businesses himself. Since parliament refused, Simpson founded a subsidiary. Sawmills were now cutting wood for export to California and East Asia, salmon and cranberries were exported, and the Puget Sound Agricultural Company was established in Victoria for these purposes as early as 1843 . The first coal mine was built in Fort Rupert in the north. The SS Beaver was the first motorized ship to sail in the American Northwest (1834). In 1849 James Douglas was appointed governor of the newly created Crown Colony by the Company . Finally, the colonial power changed its course in one decisive point: in 1852 they allowed the colony to sell "uninhabited" land. It sold for a dollar an acre .

Victoria, which had barely 300 inhabitants until April 25, 1858, grew richer by 450 miners that day. Although gold had been found on the Queen Charlotte Islands in 1851, the governor kept the find secret until 1856. The Indians had sold the company 800 ounces of gold by then. But when the gold discoveries became known, 16,000 people came to Victoria in a very short time. There were also missionaries who visited the native villages. The population pressure increased rapidly.

The actual decline of the Nuu-chah-nulth began as early as 1824 with severe smallpox epidemics ( the first wave had probably reached the mainland as early as 1775, followed by measles around 1850 ), while a steady stream of prospectors moved northwards, especially after the establishment of Victoria. This rapidly increased the risk of infection, and the non-Europeans had no means of preventing it. The southern First Nations were particularly hard hit by land sales since 1852. 1850–54, Governor James Douglas concluded 14 land assignment agreements for small compensation. In addition, there was the extreme decline in the sea otter and then the beaver populations (up to around 1830 and 1860, respectively). At the same time, the Tsimshian , Haida and Coast Salish fought long wars, which were now fought with modern rifles. This resulted in considerable power shifts between the tribes and population movements, in which wars sometimes raged for years, such as between the Ahousaht and the Otsosaht, who fought for 14 years.

In 1858 William Eddy Banfield came to Barkley Sound to trade with the Huu-ay-aht. Around 1860 he established a permanent trading post which later bore his name. In 1862, however, he died under unexplained circumstances.

In 1862–63, a severe smallpox epidemic raged on the west coast , probably killing 20,000 Indians. In contrast to the early, equally severe smallpox epidemics, this time the Nuu-chah-nulth were also affected.

In 1864 there was a brief gold rush on the Sooke River, west of Victoria. In the same year there were violent clashes in the course of which Ahousaht attacked a merchant sloop and killed the crew. In the course of a vengeance, a fleet shelled and destroyed nine villages, killing 13 Ahousaht.

British Columbia

The policy towards the indigenous peoples, whose numbers decreased dramatically, changed. With the establishment of the province, British Columbia also took on the role of Indian affairs , which the Department of Indian Affairs directed. Thus the Indian policy was regulated by the state. First of all, the natives should be Christianized more intensely. In 1875 a Catholic mission was established in Hesquiat . There was considerable resistance to proselytizing. T. assumed syncretistic forms, but had no prospect of success.

In 1864, during the Queen's birthday celebrations, the Indians of British Columbia asked the governor to protect their land, but the following year the Vancouver Island Legislative Assembly called for a bid for Indian land to be freed. In 1866, the Indians were also prohibited from acquiring their own land ( Pre-Emption Ordinance ). It is probably no coincidence that numerous islands, stretches of coast, bays, rocks, etc. were given English names during this time, which mostly reflect the phase of European discovery.

In 1867 Vancouver Island became part of British Columbia, and in 1871 Canada. This made Canada responsible for the reserves.

Canada

Tightening

For years the Canadian government tightened the policies of the HBC and the provincial government. This was the case, for example, with commercial fishing, which was forbidden to Indians from 1871 to 1923. They were also deprived of their right to vote from 1872 to 1949, in 1876 even the communal one. From 1880 to 1927 they were also denied the right to assemble and until 1970 they were disadvantaged when buying land. Potlatch was banned in 1885 (until 1951), and commercial fishing was again banned in 1888.

In 1875 the government ended the Indian Board system through a system of two superintendencies , which had executive power. After all, in 1884 the government rejected an initiative to evict Indians from any kind of valuable land. Instead, most of the Nuu-chah-nulth tribes were assigned reservations by Indian Commissioner Peter O'Reilly between 1881 and 1889, similar to the Makah in the United States in 1855. Nevertheless, the government transplanted the Songhees from the Victoria area in 1903 , a policy that was not officially abandoned until 1908.

When the McKenna-McBride Commission visited the reservations of British Columbia from 1913, they also visited the West Coast Agency , which coincided with the area of the Nuu-chah-nulth tribes. Two reserves were greatly reduced in size (over 340 acres around Port Alberni and Barkley Sound ), but quite a few were added. For example, the "Checkleset Tribe" received 7.8 acres , the "Clayoquot Tribe, Manhauset Band" 10 acres , "Esperanza Inlet Tribe, Nuchatlitz and Ehatisaht Bands (together)" 10 acres , plus a cemetery of 3.75 acres and so on ., over 665 acres in total .

The hereditary chiefs or traditional chiefs ( Ha'wiih ) presented a special "problem" . Although they fulfilled the British basic demand for indirect rule, which the Canadian government also initially pursued, they at the same time prevented access to their "subjects" and, in the eyes of the Canadian government, opposed their ideal of equality between individuals. An amendment to the Indian Act of 1951 therefore stipulated that each band council (tribal council) had to consist of one chief and one councilor for every 100 tribal members. A minimum of two and a maximum of 12 consultants had to be used. This brought a potential split within the tribes into play.

Resistance and support

However, the passages of the British Columbia Land Act of 1874 that disregarded Native American claims were cashed in in 1875. Governor General Lord Dufferin even urged fair treatment of these claims. But it took more than a decade before the first land rights were at least recognized in principle. As early as the 1980s, Indians toured Germany, in 1892 they took part in the Chicago Columbian Exposition and anthropology became increasingly interested in their culture. In 1896, the British Columbian Indians asked the government to protect their salmon fishery, but officials destroyed their nets the following year. The unresolved legal issues at least prompted the government to draw up a list of the rights to which the Indians are entitled.

In 1906 a delegation of British Columbia chiefs, led by Squamish chief Joseph Capilano, met with King Edward . In 1910 the Conference of Friends of the Indians of BC was founded . After all, the agreement between Canada and the United States that ended the hunt for marine mammals took into account the needs of the aborigines in British Columbia, whose total number was estimated at 21,489 in 1913. In 1916-27 the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia tried to advance the land issue. But in 1927 the Indian Act expressly forbade raising money and hiring lawyers (until 1951). In 1931 the Native Brotherhood of British Columbia was founded.

In 1920 all efforts to regain autonomy suffered another setback. All children from 7 to 15 years of age were now forced to attend the residential schools (see below).

After all, Indians were allowed to fish commercially from 1922 and use motor boats to do so from 1923. In 1949 they were allowed to take part in the elections for the provincial parliament for the first time, and in 1960 for the national parliament.

Serious land rights negotiations began in the course of the 1970s, and in 1980 the Nuu-chah-nulth formulated their demands and presented them to the government. In 1990 these demands resulted in the Indian Self-government Enabling Act , which was supposed to strengthen self-government . An agreement in principle took place in 2001.

"Integration" and recovery

In 1835 the total number of Nuu-chah-nulth is estimated at only 7,500, while before 1780 their number is estimated at around 25,000. By 1881, their number had shrunk to 3,613, but it wasn't until 1924, when 1,459 people, that they bottomed out. In 1927 the Indian Act deprived them of the right to set up a political advocacy group.

It was not until 1951 that the potlatch ban, which had existed since 1884, was lifted. In 1958 the first associations of the various Nuu-chah-nulth groups were formed. At the state level was 1968, the National Indian Brotherhood , from 1982, the Assembly of First Nations ( Assembly of First Nations , AFN) emerged. However, the comparatively small group of Nuu-chah-nulth played only a minor role in comparison to the Cree or other larger nations until 2009. After all, their number had recovered to 5,775 by 2005.

First censuses

The first censuses, including the Nuu-chah-nulth, were held in 1881, 1891, and 1901. In 1881 and 1891 there were the following membership figures for the then twenty bands :

|

In the west, the Indian agent Harry Guillo did the census. Between Otter Point and Cape Cook, his district comprised 20 Nuu-chah-nulth tribes, from the Pacheena in the south to the Chekleset in the north. His results are considered particularly reliable because he spoke the languages and knew the conditions very well. The total number counted was around 3,600, but it continued to decline. Therefore, some bands went into larger associations.

Forced Adoptions and Residential Schools

The declining number of inhabitants in the 20th century (in contrast to the 19th) is less due to illnesses and open conflicts, to economic and social decline, than to the forcible removal of children from families. They have been sent to mission schools since the 1890s. In the twenties it was believed that the "Indian problem" could be solved by admitting students to residential schools and educating them to become "new Canadians". They should forget their mother tongue, give up their cultural habits and lose their self-confidence. The isolated situation, plus the widespread drill in all schools , but perhaps also the special location and organization of church schools, led to brutal conditions. Conditions in some of these schools were such that numerous cases of tuberculosis and severe abuse caused the death rate to skyrocket up to 75%.

It was not until the sixties that the “locals” were allowed to use their mother tongue again - if they still knew it. The last residential school was not closed until 1983 in Tofino .

1991-93 examined a Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples the conditions at the residential schools and came to devastating results. In Ontario alone, there had been more than ten thousand brutal assaults, with sexual abuse very common. The Nuu-chah-nulth were also badly affected. In 1998, Canada's Minister of Indian Affairs officially apologized to the former students.

The Aboriginal Healing Foundation , established in 1998, was to give Canadian $ 350 million (CAD) to groups and their therapy projects. But after two years only $ 2.5 million had been spent. The churches also participated in making amends by funding therapy facilities for school survivors. It was not until 2005 that an agreement was reached on 10,000 CAD for each of the approximately 80,000 former children - a total of around one billion dollars. The cases of particularly brutal assaults are still pending before the courts. Today one tries to counteract depression and violence, often the long-term effects of these processes, through campaigns against alcohol and other drugs . The whole process, i.e. the attempt to wipe out a culture, is still not recognized as a crime.

On the other hand, nationwide credit card companies, lenders from the gray capital market, but also travel providers and agents are now trying to offer their products to the victims who are known by name.

Culture losses

In view of the distress in which the Nuu-chah-nulth stood as a social unit for more than a century and a half, it is not surprising that their cultural expressions also weakened. Here, too, only a few hints. Since the Catholic missionary work, the religious impulses weakened. The ban on the potlatch (1884–1951) not only further undermined the position of the chiefs, but also almost wiped out a central element of culture, which is particularly emphasized by the practice of ceremonies. The art of carving and painting, which of course derives its right to exist in the context of culture mainly from its involvement in ceremonies, also stepped on the spot. Only a few still mastered the relevant crafts, so that the low point can be seen in the 1950s. Nevertheless, the holistic art tradition has never been broken.

But the cultural decline happened very unevenly. The great wood carvings, especially the stakes, had long drawn the attention of anthropologists , ethnologists, and those interested in art. Starting with James Cook, numerous objects found their way into museums and collections. Yet in 1904 the largest building, which was Whalers' Shrine of the Mowachaht in Yuquot sold, mined and after New York spent. This sanctuary was reserved for the chief and was used to carry out whaling rituals, but also as a burial place for chiefs. This is how the skulls of Chief Maquinna's ancestors were deposited here. Eight generations were worshiped this way in his day. Sometime between 1817 and around 1900 the shrine was moved a little further away from Yuquot (perhaps merged with another) and probably reduced in size. Today it consists of 88, z. Sometimes monumental, figurative representations that were probably created between the 18th and 19th centuries. Thus, even those who were interested in the Nuu-chah-nulth culture had a share in its decline in the end. The irony of history is that the return and occupation with the works scattered around the world should be one of the prerequisites and consequences of the revival.

Retrieval of resources

For the Nuu-chah-nulth, the struggle for resources, primarily for their children, but then especially for their natural environment, the ocean and the rainforest, is of far greater importance than for the ecological movement. Here, cultural motives play a much stronger role, because the continued existence of the culture of the indigenous peoples depends heavily on the state of the natural environment. That is why there is broad agreement with the external supporters in terms of the approach and the goal, even if the motives do not entirely coincide. For example, there are differences of opinion on the question of the right to traditional whaling. But initially the indigenous peoples were left alone, with their cultural peculiarities threatened by the economic interests of the timber companies.

The dispute ignited at the most sensitive point of the Nuu-cah-nulth culture, and at the same time threatened their livelihood, the fishing: In 1955 the (bribed) Minister of Forestry granted logging rights for more than half of the Clayoquot Sound to MacMillan Bloedel , the then predominant timber company. The following year, British Columbia Forest Products received the rest of the sound area. The areas affected by the deforestation from 1960 onwards were initially small, but rainfall washed mud into the rivers, so that vital fish stocks for the Nuu-chah-nulth collapsed. The individual, widely dispersed groups could not counter this development. In 1958, therefore, tribes united for the first time to form the West Coast Allied Tribes , from which in 1978 the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council emerged . Shortly afterwards (1979) the Friends of Clayoquot Sound were founded in Tofino , initially only to document the damage that had already been done.

In 1981 this resistance was combined with that of the Nuu-chah-nulth. In 1982 a commission was set up to investigate damage to fish stocks. In 1984 the inhabitants of the island of Meares proclaimed the island , which was directly threatened by deforestation, to be a tribal park and demanded - for the first time - protection in recognition of its cultural autonomy. Against the recommendation of the commission and against indigenous resistance, the provincial government confirmed logging rights for 95% of the area, whereas the Nuu-chah-nulth proceeded with road blockades. In 1985, an interim order stopped the deforestation, but in 1988 McMillian Bloedel tried to create a fait accompli through an unauthorized forest road into an area not approved for use. In 1989, nature conservation associations and representatives of the tourism association joined forces for the first time, and thus a third ally, but in 1991 they broke off negotiations.

In 1992 the dispute broke the narrow provincial framework and also crossed national borders. International boycotts of wood meant that the smallest and most remote part of the area around the Megin Valley was placed under protection, but the rest was allowed to be cleared using the deforestation method that is common in Canada. Over 900 people were arrested when the forest roads around Kennedy Lake were blocked .

But negotiations have now begun on the participation of the indigenous peoples, which resulted in their being granted a provisional right of veto in 1994. An autonomy statute for the First Nations has been discussed in Canada since 1995 .

In 1997 the Regional Aquatic Management Society (RAMS) was founded, a society in which Nuu-chah-nulth and non-indigenous people came together, fishermen, environmentalists, members of the government and municipalities, a total of over 70 groups, came together to protect the coastal region.

In 2000, UNESCO made the entire Clayoquot Sound a biosphere reserve . Since then, several protected areas have been created in the form of Provincial Parks , the Pacific Rim National Park , which has existed since 1970 and was rededicated in 2001 to recognize the participation of the First Nations in the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve , also plays an important role . A working group of the provincial government and the First Nations developed comprehensive land use plans by 2005 with the aim of protecting 40% of the rainforest. The Quu'as partnership in the national park was also set up to establish and maintain the West Coast Trail . It is a corporate joint venture of Pacheedaht First Nation , Ditidaht and Huu-ay-aht with Parks Canada , which also jobs have been created.

The timber company MacMillan Bloedel and the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations founded Iisaak Natural Resources Ltd. in 2005 . , ( Iisaak , pron. Isok, in German respect) a society for sustainable forest management in Clayoquot Sound. This is to remain 51% in Nuu-chah-nulth hands through Ma-Mook Natural Resources Limited . The takeover of Bloedel by Weyerhaeuser (1999), one of the largest timber companies in the world, has not changed anything. In March 2007, the Tla-o-qui-aht were able to enforce that a 10,000-acre population (approx. 40 km²) of old rainforest in the upper Kennedy Valley would be protected for another five years.

However, from the Nuu-chah-nulth's perspective, the reclamation of the forest and fish stocks is only the first step towards restoring an environment in which their culture can again exist independently. In this way, the sea otters, which were critically endangered, could be made home again. Nonetheless, foreign economic interests still stand against the Nuu-chah-nulth's resource conservation. At the end of August 2007, Norwegian Grieg Seafood approved a salmon farm open to the sea (similar to May), although this runs counter to long-term agreements on the protection of wild salmon stocks. It also endangers the sea lions , who regard the salmon as prey, and get caught in the nets and suffocate.

requirements

On December 11, 2000, the Nuu-chah-nulth, more precisely 14 of their tribes, made an offer to the governments of Canada and British Columbia. In it, they claimed back land amounting to almost 3,400 km², in accordance with the previously granted right of first refusal. In addition, there was the protection of resources, for which purpose appropriate funds should be set up. The right to certain quantities of marine animals should be established in accordance with the increase in population. At the same time, the traditional types were specified. In addition, there were protected areas, which should encompass a wide stretch of coast, whereby in some areas the rights of use should be shared, in others exclusively with the Nuu-chah-nulth. After all, the estimated $ 12 billion loss due to overexploitation in their areas should be offset by just under $ 1 billion.

Against the opposition of the Canadian government, but also that of the USA, Australia and New Zealand , the UN passed a resolution on September 13, 2007, in which not only the elimination of any disadvantage or the right to have a say in matters, but also also the right “to remain distinct”. The Canadian ambassador was particularly bothered by the passages that concern soil and raw materials and those in which a voice is demanded.

Economic independence

While the efforts on the ecological and cultural level were in the public eye, the Nuu-chah-nulth Economic Development Corporation was founded in 1984 , which tries to improve the economic situation of the 14 member nations of the Nuu-chah-nulth Council. In 1997 this area of activity was extended to all “aboriginals” in the Nuu-chah-nulth area. It grants loans of up to CAD 500,000 for commercial activities, cooperates with Aboriginal Business Canada (ABC), provides a mentoring program for entrepreneurs and supports numerous sole proprietorships.

The Nuu-chah-nulth earned their livelihood mainly through fishing (commercial and subsistence farming ) and work in canning factories, also through logging, but now also in tourism. In the past few years, traditional basketry and other handicraft techniques have been revived. This includes, above all, carvings in traditional motifs, which are now being further developed. They benefit from a rapidly expanding art market.

Overall, the impoverishment of the Nuu-chah-nulth communities has moderated, but a significant number of them have to seek their livelihood outside of the tribal areas. At the same time, there have been major imbalances that have occasionally led to considerable wealth accumulation, especially in the sale of timber.

In November 2009 the Ahousaht, Ehattesaht, Mowachaht / Muchalaht, Hesquiaht and Tla-o-qui-aht filed for admission to commercial fishing ( Ahousaht Indian Band And Nation v. Canada Attorney General, 2009 BCSC 1494 ).

Current numbers

The 15 member tribes of the Nuu-chah-nulth in Canada, with a total of over 10,000 registered members, are of very different sizes. Below are their names and their respective total numbers according to the indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada information (as of October 2016). This is followed by the number of those living within their own reserves, then those in other reserves, and finally the number of those living outside the reserves. There may be slight deviations, because some live on crown land.

| tribe | registered relatives |

in their own reserve |

in the foreign reservation |

outside the reserves |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahousaht | 2146 | 750 | 91 | 1324 |

| Ditidaht | 773 | 173 | 68 | 532 |

| Marriage seam | 491 | 104 | 44 | 333 |

| Hesquiaht | 733 | 124 | 34 | 575 |

| Hupacasath First Nation | 328 | 132 | 17th | 179 |

| Huu-ay-aht First Nations | 719 | 100 | 34 | 585 |

| Ka: 'yu:' k't'h '/ Che: k: tles7et'h' First Nations | 570 | 162 | 19th | 389 |

| Mowachaht / Muchalaht | 616 | 226 | 35 | 355 |

| Nuchatlaht | 162 | 25th | 11 | 126 |

| Pacheedaht | 283 | 97 | 29 | 157 |

| Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations | 1118 | 377 | 42 | 699 |

| Toquaht | 151 | 9 | 11 | 131 |

| Tsehaht | 1185 | 437 | 39 | 709 |

| Uchucklesaht | 225 | 27 | 6th | 192 |

| Ucluelet First Nation | 664 | 205 | 17th | 442 |

All of these numbers depend on the definition of Status Indians . If one of the parents does not have this status, the children of both of them do not receive this status either. So marriages with non-status Indians automatically mean that the children are no longer considered to be members of the First Nations . If the current legal and demographic situation were updated, there would be practically no more Indians in about six generations. So although the population in the reservations is growing, the number of status Indians is decreasing. Therefore, their representatives are calling for a change in Indian law on this point.

Of the approximately 8,960 members of the 15 Canadian Nuu-chah-nulth groups, around 3,000 lived in their reservations in 2008, around 400 more in other reservations, while just under 5,900 lived outside of them. In 2014, of the approximately 9,900 members, only a little more than 2,700 were in their own reserves, a further 500 in other reserves, and around 6,300 lived outside the reserves. In October 2016, 10,164 Nuu-chah-nulth were counted, of which 2,948 lived in their reservations, 497 in other reservations and 6,728 outside. The proportion of reserve residents fell from around a third to a quarter between 2008 and 2014, but has been increasing again since then, so that it is now 29%.

In 2003, exactly 2,492 people were registered as members of the Makah at the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the USA. Thus, the Nuu-chah-nulth group comprises over 12,500 members in 16 tribes.

Historical memory

The conception of the course of Nuu-chah-nulth history has been greatly expanded by Western methods and results. Nevertheless, both the mythological and the family tradition (provided the members of the families entitled to narrate are willing to report these outsiders and have them translated) represent an extremely important group of sources. This applies above all to the early phase and the first century of the European phase, in which the European reports only provide sporadic insights that are shaped by their prior understanding. But that also applies to those bands that came into the focus of Europeans and Canadians very late. In addition, ethnological and anthropological work has greatly expanded the understanding of the overall culture.

But neither written sources nor narratives (apart from symbols, chants, dances and other forms of memorization) are sufficient as sources familiar to the European observer. The concept of the source is greatly expanded in this culture by the inclusion of important places in the "wilderness". On the nature trail of the Ahousaht on Flores Island , for example, there are trees that have been processed or examined for specific purposes, such as building canoes or extracting delicate tree fibers for clothing. These are called Culturally Modified Trees (CMTs). Another tree is reminiscent of a massacre during the murderous war against the Otsosaht in the early 19th century, and yet another one of the vision of one of the most important shamans. In connection with the knowledge of the residents, the forest represents a kind of historical source, which is why these forest areas are also called CMT archives. Self-awareness and an understanding of history are developed and taught using artefacts that are rarely included in European history. This also makes the resistance to the deforestation of certain forest areas more understandable, because it is, as one Ahousaht chief put it, like destroying the only existing copy of a historical work in a library.

Radical reversal and knowledge of one's own culture

It is a multitude of factors that threatens the independence of the Nuu-chah-nulth culture today. On the one hand, these are events that lie in the past, which have irrevocably changed their culture and have partially deprived it of the material and knowledge base. On the other hand, there is still the economically motivated conversion of their natural environment (above all the destruction of the forest, whereby trees have recently been taken into account as historical works, but also the threat to fish stocks), on the other hand, poverty and the associated emigration of young people in particular, and Dependence of the remaining on the state and industry.

Three significant changes in recent years are, on the one hand, the protection of considerable parts of the old tribal areas as provincial and even national parks. This creates an income opportunity for many reserve residents through tourism that neither destroys resources to the extent that they have so far, nor keeps them dependent on state welfare.