General election in India 1971

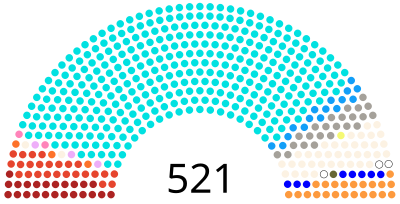

The 1971 parliamentary elections in India took place from March 1 to 10, 1971. The Lok Sabha , the second chamber of the Indian parliament, was elected. It was an early election - the first in independent India - as the legislature of the Lok Sabha elected in 1967 would have lasted until March 1972. Two wings of the Congress Party , which had split in 1969, faced each other in the election : on the one hand the Congress (R) under the leadership of the previous Prime Minister Indira Gandhi , and on the other hand the Congress (O) under the leadership of Morarji Desai . The election was clearly won by the Congress (R), which won more than two thirds of the parliamentary seats. The turnout of 55.3% was below that of the previous election (61.0%).

prehistory

The Congress Party after 1967

The 1967 elections for both Lok Sabha and the parliaments of most states were widely viewed as a defeat for Congress. The Congress Party under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi took up a little more than half of the parliamentary seats in the Lok Sabha, thus maintaining the government majority, but losing around 20% of the parliamentary seats it had previously held and thus the previous super-majority. The Congress party was internally divided. After Jawaharlal Nehru's death in 1964, there was no generally recognized leader. Indira Gandhi, who had served as Prime Minister since 1966, already had a difficult position as a woman in the exclusively male leadership of the Congress Party. There were ideological differences within Congress. While some wanted to continue or even accentuate Nehru's socialist course, others more or less advocated a reorientation. In addition, there were a number of regionally influential party sizes who wanted to maintain their sphere of influence, and for this reason alone were interested in a relatively weak central power. The so-called “Syndicate”, a group of older, more conservative Congress politicians, mostly from non- Hindi states , had a particular influence .

Dispute over bank nationalization

Indira Gandhi turned out to be an exponent of the left wing of the Congress Party. With her politics she won the support of the young, more radical party members, but increasingly came into opposition to the traditional, more conservative party elites. The question of the nationalization of Indian banks developed into a central point of contention. The vast majority of the Indian banking sector was privately owned. The communists, socialists and party links in Congress have long criticized the alleged failure of the banks to contribute enough to the country's economic development. In particular, so the allegations, they did not care enough about the unprofitable granting of small loans to farmers and small businesses (craftsmen, etc.), who often had no access to credit at all. To solve this problem, the nationalization of the big banks was called for. General socialist ideas about a state-controlled and developed economy and a distrust of the concentration of capital in private hands also flowed into this demand. On the part of the banking sector, the opponents of this concept argued that such a state takeover was not necessary, since the powers of the state Reserve Bank of India were already very extensive and this already had the opportunity to intervene in almost every aspect of the banking system. It was also denied that banks were not making enough efforts to lend. Government agencies have expressed concerns that nationalization will result in very high compensation costs and that government institutions may not have sufficient skilled staff to manage banking operations.

On February 1, 1969, the Banking Laws (Amendment) Act , initiated by the government of Indiana, came into force. The law stipulated a reorganization of the supervisory boards of the major Indian banks with more than 25 crore (250 million) rupees (at that time US $ 33.3 million, DM 134 million ). The majority of the supervisory boards had to be made up of non-industrialists. In addition, a “National Credit Council ”, chaired by the Minister of Finance, was introduced as the central banking supervisory body . Representatives from agriculture, trade, industry and other professional groups were represented in the credit council. However, these stricter state controls were not enough for the political left, who called for the full nationalization of the big banks. Indira Gandhi initially opposed these demands at the meeting of the All India Congress Committee (AICC) in April 1969, but not out of general opposition, but with the argument that the state did not have enough specialists available to run the banks competently. In the following period, however, the Prime Minister changed her mind and came to a radically different assessment. In July of the same year, she spoke out in favor of bank nationalization at a meeting of the AICC in Bangalore . So they met with the opposition of the Finance Minister Morarji Desai , who argued that the previous "social control" ( social control ) is sufficiently above the banks.

On June 29, 1969, Indira Gandhi publicly announced her intention to nationalize the big banks and at the same time declared that she wanted to take over the finance ministry on her own. Finance Minister Desai was offered to replace the post of Deputy Prime Minister. Desai refused and he was dismissed as finance minister on July 16, 1969. With effect from July 19, 1969, the Banking Companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertakings) Ordinance , a presidential ordinance , nationalized a total of 14 banks, each with more than 50 crore rupees deposits and together controlling more than 70% of Indian deposits. Many observers suspected that Indira Gandhi's decision was not only guided by purely economic considerations, but also arose out of power-political calculations. Their opponents in the “Syndicate” were divided over the question of nationalization. Some had spoken out in public for this step ( Kamaraj and Chavan ), others were known to be against it ( Nijalingappa , Patil ). The Prime Minister did not expect any unified resistance on this issue. On the other hand, the rejection by the conservative opposition ( Swatantra , Jan Sangh ), which above all criticized the urgent procedure in which the measure was carried out, and lodged a constitutional complaint with the Supreme Court , was unanimous. The presidential ordinance was later replaced by a retroactive law. However, Indira Gandhi's government suffered a significant setback when the Supreme Court ruled on February 10, 1970, with a 10-1 vote that the law was ineffective. The dispute over the banks subsequently developed into one of the numerous small and long-term wars that Indira Gandhi waged with the Supreme Courts of India.

1969 presidential election

During the intensification of the dispute over bank nationalization, the Indian presidential election took place. The opponents of Indira Gandhi in the Congress Party saw here the opportunity to bring Indira Gandhi a defeat and managed to have Neelam Sanjiva Reddy , one of the members of the "Syndicate" nominated as an official Congress Party candidate. At the same time, the previous Vice President VV Giri announced his candidacy as a non-party. Giri was considered to be the exponent of the left spectrum and while Indira Gandhi remained formally neutral in the election battle, her preference for Giri was well known. In an extremely tight vote on August 16, 1969, Giri was ultimately elected with 50.9% of the weighted MPs. The vote showed that a large part of the Congress Party deputies had not supported the preferred candidate of the party leadership, but the candidate Indira Gandhi.

Division of the Congress party

| Political party | Seats |

|---|---|

| Government: | |

| Congress (R) | 228 |

| often coordinating with the government: | |

| Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) | 24 |

| Communist Party of India (CPI) | 24 |

| Core opposition: | |

| Congress (O) | 65 |

| Swatantra | 35 |

| Jan Sangh | 33 |

| Other: | |

| Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPM) | 19th |

| Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP) | 17th |

| Praja Socialist Party (PSP) | 15th |

| Other and independent | 59 |

| vacant | 3 |

| Speaker | 1 |

| total | 523 |

The internal crisis of the Congress Party was decisively exacerbated by the outcome of the presidential election. The Congress party leadership felt increasingly outmaneuvered by the Prime Minister. The tensions and mutual accusations escalated and on November 12, 1969, Congress Party President Nijalingappa finally declared the expulsion of Indira Gandhi from the Congress Party for anti-party behavior and called on the parliamentary faction of the Congress Party in the Lok Sabha to elect a new chairman, i.e. de facto to vote out the Prime Minister. However, the parliamentary group did not follow this request and expressed its confidence in Indira Gandhi with a majority of 330 of its 427 MPs. However, around 60 congressmen elected Moraji Desai as their chairman two days later and went into the opposition. The Congress party was thus divided. Indira Gandhi's government had lost its previous absolute majority in parliament and was dependent on the support of other parties, especially the communists, socialists, DMK, Akali Dal and some independents. As a result, the split deepened and each of the two congressional factions held its own meetings and elected their own party bodies. The Indian Election Commission recognized both factions as separate parties, but gave the old party names to neither of the two factions. Instead, the parliamentary groups were given new names. Indira's faction was named Indian National Congress (Requisition) ("Congress (R)") and the faction in opposition to this faction was named Indian National Congress (Organization) ("Congress (O)"). The election symbol of the old congress party, the two oxen under the yoke , was not given to either of the two successor parties. The Congress (R) received a cow with a calf as a new election symbol, and the Congress (O) received a woman with a spinning wheel ( chakra ).

- Congress party election symbols

On December 27, 1970, President Giri dissolved the Lok Sabha at the request of Indira Gandhi and announced that new elections would be held for March 1971.

Election campaign

In some areas there were electoral alliances between Indira's Congress and the CPI, the Muslim League , the Praja Socialist Party (PSP), and in Tamil Nadu with the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). On the other hand, there were electoral agreements between Congress (O), Swatantra, Jan Sangh and the Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP). In the election campaign, Indira Gandhi was clearly the dominant personality. This was partly due to the opposition, which - without presenting a corresponding common opponent - made the Prime Minister the target of her attacks. The prime minister was able to respond skillfully to the opposition's initial election slogan Indira Hatao (" Away with Indira") with her own rhymed election slogan Garibi hatao, desh bachao (गरीबी हटाओ देश बचाओ, "Away with poverty, save the country"). The opposition four-party electoral alliance was ideologically extremely heterogeneous, did not give up a united front and therefore offered its opponents from Indira's congress numerous areas for attack. Swatantra was caricatured by them as the party of princes and big business, Jan Sangh as the party of communalism and the Samyukta Socialist Party were accused of being associated with two such parties. In contrast, Indira Gandhi's Congress stylized itself as a party of social progress. The conservative opposition painted the picture of an impending threat to democracy from an authoritarian rule by Indira Gandhi. Overall, the verbal disputes remained relatively civilized and all parties emphasize their obligation to progress India's society.

In Jammu and Kashmir, the All Jammu and Kashmir Plebiscite Front , which called for a referendum on the political future of Jammu and Kashmir, announced that it would run candidates for the election. During a visit to Kashmir in December 1970, the Prime Minister stressed that the state's affiliation with India was final and should not be questioned. A little later, the front was banned under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 and its candidates were banned from voting. Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah was banned from staying in Kashmir for three months.

Conditions in the state of West Bengal caused particular concern. There, in 1967, former CPM supporters turned away from the CPM party leadership under the influence of the Maoist Cultural Revolution in the People's Republic of China and began the armed revolutionary struggle. The rebels were later referred to as " Naxalites " after the western Bengali town of Naxalbari , where the uprising began . The movement later expanded to other states where the communists were strong, particularly Andhra Pradesh. Criminal and anti-social elements mixed in the movement and Calcutta became a center of violence. In the initial phase, the movement primarily chose leadership cadres of the CPM as victims of its terrorist attacks. Indirectly, it helped the Congress party in the election.

Election dates

The election dates were spread over different days in the individual states and union territories. The longest - over a full week from March 1 to 6, 1971 - were the polling stations in Nagaland. In one constituency each of Jammu and Kashmir as well as Himachal Pradesh the election was postponed to a later date. In West Bengal, due to the tense security situation, the last election was on March 10, 1971, also in order to be able to transfer as many police forces as possible from other states to monitor the implementation of the elections.

| State or Union Territory |

Election dates |

|---|---|

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | March 1, 1971 |

| Andhra Pradesh | March 5th 1971 |

| Assam | March 1st and 4th, 1971 |

| Bihar | March 1st, 3rd and 5th, 1971 |

| Chandigarh | March 5th 1971 |

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli | March 5th 1971 |

| Delhi | March 5th 1971 |

| Goa , Daman and Diu | March 4th 1971 |

| Gujarat | March 1st and 4th, 1971 |

| Haryana | March 5th 1971 |

| Himachal Pradesh | March 2nd and 5th, 1971 |

| Jammu and Kashmir | March 4th, 6th and 7th, 1971 |

| Kerala | March 6th and 9th, 1971 |

| Laccadives, Minicoy and Amine Divas | March 1, 1971 |

| Madhya Pradesh | March 1st and 4th, 1971 |

| Maharashtra | March 1st, 4th and 6th, 1971 |

| Manipur | March 1st, 4th and 7th, 1971 |

| Mysore | March 4th and 6th, 1971 |

| Nagaland | March 1-6, 1971 |

| Orissa | March 5th 1971 |

| Pondicherry | March 4th 1971 |

| Punjab | March 5th 1971 |

| Rajasthan | March 1st, 4th and 6th, 1971 |

| Tamil Nadu | March 1st, 4th and 7th, 1971 |

| Tripura | March 7, 1971 |

| Uttar Pradesh | March 1st, 3rd and 5th, 1971 |

| West Bengal | March 10, 1971 |

- ↑ In the constituency 2-Mandi of Himachal Pradesh was not elected until March 16, 1971. See: Election Commission Report , p. 37.

- ↑ In constituency 4-Ladakh was only elected on June 6, 1971. See: Election Commission Report , p. 37.

- ↑ The election dates for Kerala were originally March 3rd and 6th, but the election was postponed from March 3rd to March 9th 1971 due to a strike. See: Election Commission Report , p. 37.

Election mode, constituencies and voting process

As is customary in Indian parliamentary elections, the election was based on a relative majority vote in 518 constituencies. All persons who were at least 21 years old on January 1, 1971 were entitled to vote. People who turned 21 between January 1, 1971 and the election date could not vote because the electoral registers were no longer updated. The distribution of the constituencies among the individual states and union territories largely corresponded to that of the previous election in 1967. The only difference concerned Himachal Pradesh. With the State of Himachal Pradesh Act, which came into force on January 25, 1971, in 1970 , the former union territory of Himachal Pradesh became a fully-fledged federal state. The number of Lok Sabha constituencies was adapted to the population and reduced from 6 to 4. 76 constituencies were reserved for members of the scheduled castes (SC) and 36 for those of the scheduled tribes (ST). Compared to the 1967 election, this was one less SC constituency in Haryana and one less ST constituency for the Laccadives, Amindives and Minicoy.

One MP was appointed by the President to represent the population of the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), where there was no election.

Turnout was highest in southern India and lowest in the Hindi states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, as well as Orissa. Despite the Naxalite uprising , which tried to sabotage the elections, it was also relatively high in West Bengal.

| State or Union Territory |

electoral legitimate |

Voters | electoral participation |

Invalid votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | 63.122 | 44,531 | 70.55% | 0.01% |

| Andhra Pradesh | 22,697,905 | 13,420,873 | 59.13% | 2.59% |

| Assam | 6,268,273 | 3,177,170 | 50.69% | 4.74% |

| Bihar | 31,019,951 | 15.186.628 | 48.96% | 1.92% |

| Chandigarh | 116,685 | 73,418 | 62.92% | 1.52% |

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli | 33,012 | 23,037 | 69.78% | 5.99% |

| Delhi | 2,016,396 | 1,314,480 | 65.19% | 1.26% |

| Goa , Daman and Diu | 435.168 | 243,341 | 55.92% | 3.06% |

| Gujarat | 11,535,312 | 6,401,309 | 55.49% | 4.24% |

| Haryana | 4,768,740 | 3,068,699 | 64.35% | 2.48% |

| Himachal Pradesh | 1,708,667 | 703.727 | 41.19% | 3.08% |

| Jammu and Kashmir | 2,097,623 | 1,219,085 | 58.12% | 4.29% |

| Kerala | 10,217,893 | 6,593,446 | 64.53% | 0.98% |

| Laccadives, Minicoy and Amine Divas | 14,977 | 0 | 0.00% | - |

| Madhya Pradesh | 19,578,837 | 9,397,900 | 48.00% | 6.02% |

| Maharashtra | 24,008,058 | 14,391,012 | 59.94% | 3.32% |

| Manipur | 543,407 | 265,495 | 48.86% | 2.16% |

| Mysore | 13,789,186 | 7,917,061 | 57.41% | 3.43% |

| Nagaland | 275,459 | 148.125 | 53.77% | 0.07% |

| Orissa | 10,864,978 | 4,693,064 | 43.19% | 4.92% |

| Pondicherry | 246,789 | 172.992 | 70.10% | 1.68% |

| Punjab | 6,950,385 | 4,163,167 | 59.90% | 2.06% |

| Rajasthan | 13,244,556 | 7,158,072 | 54.05% | 3.26% |

| Tamil Nadu | 23,064,983 | 16,565,649 | 71.82% | 3.72% |

| Tripura | 703.736 | 428.203 | 60.85% | 3.65% |

| Uttar Pradesh | 45.856.709 | 21,099,018 | 46.01% | 2.55% |

| West Bengal | 22,068,325 | 13,667,300 | 61.93% | 4.31% |

| total | 274.189.132 | 151.536.802 | 55.27% | 3.26% |

- ↑ a b No election was held in the Union Territory of the Laccadives, Minicoy and Amindives because there was only one candidate. See report on p. 37.

Results

Overall result

The election ended with a victory for Indira Gandhis Congress (R) across the board. The Congress (R) was able to increase its share of the vote by 2.9 percentage points to 43.69% compared to the result of the as yet undivided Congress party in the last election in 1967. The gain in electoral district seats was much clearer. Here the Congress (R) got 352 seats (68%) and thus achieved a two-thirds majority of seats in the Lok Sabha. In most of the 27 states and union territories he won an absolute majority of the constituencies. The six exceptions were Tamil Nadu, Kerala, West Bengal, Gujarat, Tripura, and Nagaland. The competing Congress (O) ended up in second place in terms of the vote with 10.4%, but only managed to win 16 constituencies (3.1%). 11 of the 16 Congress (O) MPs were elected in Gujarat, the remaining 5 were spread across the three states of Bihar (3), Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu (one each). The Swatantra party, which in 1967 was the third strongest party in terms of votes and the second strongest party in terms of mandate, was almost eliminated as a national party. You could only win 3.1% of the vote and 8 constituencies (1.5%). At Swatantra, the lack of a convincing leader was particularly noticeable. The 90-year-old C. Rajagopalachari , who had contributed significantly to the party's success in 1967, could no longer fill this role. The 8 Swatantra MPs came from three states: Rajasthan (3), Orissa (3) and Gujarat (2). The Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) did slightly better than Swatantra . In 1967 it had become the second largest party in terms of votes. This time it came in third place with 7.35%. She won 22 constituencies and thus lost more than a third of her previous parliamentary seats. The elected BJS MPs came exclusively from Hindi-speaking states, half from Madhya Pradesh.

In the left-wing political spectrum, the communists (CPM and CPI) were able to increase their share of the vote a little and gain 6 parliamentary seats. This brought them to 9.3% of the mandates. The CPM outstripped the CPI in terms of votes and mandates. The stronghold of the CPM was West Bengal, where the party won half of all constituencies (20 out of 40) and replaced the Congress Party as the strongest party. The election was a disaster for the two socialist parties Praja Socialist Party (PSP) and Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP). They lost massive votes and were reduced in terms of the number of seats to small splinter parties, which together came to less than 1 percent of the seats (PSP: 2 seats, SSP: 3 seats).

What was also remarkable about the election was the relative success of regional parties. In Tamil Nadu, Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) became the strongest party with 35.3% of the vote and 24 out of 39 seats. Other regional parties with relatively strong votes were Akali Dal (30.8% in Punjab ), Utkal Congress (22.7% in Orissa ) Telangana Praja Samithi (TRS, 14.4% in Andhra Pradesh ), All Party Hill Leaders' Conference (10 , 9% in Assam ), Vishal Haryana Party (9% in Haryana ) and United Front of Nagaland (60.5% in Nagaland ). Most of these parties - disadvantaged by the relative majority voting rights - could not convert their relatively high share of the vote into seats and only won a single seat.

| Political party | Abbreviation | be right | Seats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | % | +/- | number | +/- | % | ||

| Indian National Congress (R) | INC (R) | 64.033.274 | 43.68% | 2.90% | 352 | 69 | 68.0% |

| Indian National Congress (Organization) | INC (O) | 15,285,851 | 10.43% | (New) | 16 | (New) | 3.1% |

| Bharatiya Jana Sangh | BJS | 10,777,119 | 7.35% | 1.96% | 22nd | 13 | 4.2% |

| Communist Party of India (Marxist) | CPM | 7,510,089 | 5.12% | 0.84% | 25th | 6 | 4.8% |

| Communist Party of India | CPI | 6,933,627 | 4.73% | 0.38% | 23 | 4.4% | |

| Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam | DMK | 5,622,758 | 3.84% | 0.05% | 23 | 2 | 4.4% |

| Swatantra party | SWA | 4,497,988 | 3.07% | 5.60% | 8th | 36 | 1.5% |

| Samyukta Socialist Party | SSP | 3,555,639 | 2.43% | 2.49% | 3 | 20 | 0.6% |

| Bharatiya Kranti Dal | BKD | 3,189,821 | 2.18% | (New) | 1 | (New) | 0.2% |

| Telangana Praja Samithi | TPS | 1,873,589 | 1.28% | (New) | 10 | (New) | 1.9% |

| Praja Socialist Party | PSP | 1,526,076 | 1.04% | 2.02% | 2 | 11 | 0.4% |

| Shiromani Akali Dal | SAD | 1,279,873 | 0.87% | 0.21% | 1 | 2 | 0.2% |

| Utkal Congress | UTC | 1,053,176 | 0.72% | (New) | 1 | (New) | 0.2% |

| Forward Bloc | FBL | 962.971 | 0.66% | 0.23% | 2 | 0.4% | |

| Peasants and Workers Party | PWP | 741,535 | 0.51% | 0.20% | 0 | 2 | 0.0% |

| Revolutionary Socialist Party | RSP | 724.001 | 0.49% | 0.49% | 3 | 3 | 0.6% |

| Republican Party (Khobragade) | RPK | 542,662 | 0.37% | (New) | 0 | (New) | 0.0% |

| Kerala Congress | KEC | 542.431 | 0.37% | 0.15% | 3 | 3 | 0.6% |

| Bangla Congress | BAC | 518.781 | 0.35% | 0.48% | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Muslim League | MUL | 416,545 | 0.28% | 2 | 0.4% | ||

| Vishal Haryana Party | VHP | 352,514 | 0.24% | (New) | 1 | (New) | 0.2% |

| Jharkhand party | JKP | 272,563 | 0.19% | 0.19% | 1 | 1 | 0.2% |

| Republican Party | RPI | 153,794 | 0.10% | 2.37% | 1 | 0.2% | |

| All Party Hill Leaders' Conference | APHLC | 90,772 | 0.06% | 0.02% | 1 | 0.2% | |

| United Front of Nagaland | UFN | 89,514 | 0.06% | (New) | 1 | (New) | 0.2% |

| United Goans - Sequera | UGS | 58,401 | 0.04% | 0.03% | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Other | - | 1,717,283 | 1.17% | - | 0 | - | 0.0% |

| Independent candidates | Independent | 12,279,629 | 8.38% | 5.40% | 14th | 21 | 2.7% |

| total | 146.602.276 | 100.00% | - | 518 | 2 | 100.0% | |

Result by state and union territories

The following table shows the results by state and union territories:

| State / Union Territory |

Seats | Hindu nationalists |

Congress party |

Communist / left soc. Parties |

Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | 1 | INC 1 | |||

| Andhra Pradesh | 41 | INC 28 |

CPM 1 CPI 1 |

TPS 10 Independent 1 |

|

| Assam | 14th | INC 13 | APHLC 1 | ||

| Bihar | 53 | BJS 2 | INC 39 |

CPI 5 SSP 2 |

INC (O) 3 JKP 1 Independent 1 |

| Chandigarh | 1 | INC 1 | |||

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli | 1 | INC 1 | |||

| Goa , Daman and Diu | 1 | INC 1 | UGS 1 | ||

| Delhi | 7th | INC 7 | |||

| Gujarat | 24 | INC 11 |

INC (O) 11 SWA 2 |

||

| Haryana | 9 | BJS 1 | INC 7 | VTP 1 | |

| Himachal Pradesh | 4th | INC 4 | |||

| Jammu and Kashmir | 6th | INC 5 | Independent 1 | ||

| Kerala | 19th | INC 6 |

CPI 3 CPM 2 RSP 2 |

KEC 3 MUL 2 Independent 1 |

|

| Laccadives, Minicoy and Amine Divas | 1 | INC 1 | |||

| Madhya Pradesh | 37 | BJS 11 | INC 21 | SSP 1 | Independent 4th |

| Maharashtra | 45 | INC 42 |

AIFB 1 PSP 1 |

RPI 1 | |

| Manipur | 2 | INC 2 | |||

| Mysore | 27 | INC 27 | |||

| Nagaland | 1 | UFN 1 | |||

| Orissa | 20th | INC 15 | CPI 1 |

SWA 3 UTC 1 |

|

| Punjab | 13 | INC 10 | CPI 2 | SAD 1 | |

| Pondicherry | 1 | INC 1 | |||

| Rajasthan | 23 | BJS 4 | INC 14 |

SWA 3 Independent 2 |

|

| Tamil Nadu | 39 | INC 9 |

CPI 4 AIFB 1 |

DMK 23 INC (O) 1 Independent 1 |

|

| Tripura | 2 | CPM 2 | |||

| Uttar Pradesh | 85 | BJS 4 | INC 73 | CPI 4 |

INC (O) 1 BKD 1 Independent 2 |

| West Bengal | 40 | INC 13 |

CPM 20 CPI 3 PSP 1 RSP 1 |

BAC 1 Independent 1 |

After the election

The election ended with a convincing victory for Indira Gandhi's Congress Party. The Indian Electoral Commission also submitted to the realities and in the following year recognized the Congress (R) as the legitimate successor party of the old Congress party, so that the suffix 'R' could be omitted. The election campaign had been very focused on the person of Indira Gandhi and the prime minister had raised high hopes for the common people with her promise to eradicate poverty. The following legislative period was not only the longest in Indian parliamentary history, at 6 years old, but also one of the most eventful and momentous.

literature

- Election Commission of India: Report on the Fifth General Elections in India 1971-72 . New Delhi, 1972 ( PDF ) (English)

- WEEKLY SUMMARY: Special Report: India: The World's Largest Democracy To Go To The Polls In March. Central Intelligence Agency , February 19, 1971, accessed May 27, 2017 (CIA report released for publication in 2011).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Election Results - Full Statistical Reports. Indian Election Commission, accessed on December 22, 2018 (English, election results of all Indian elections to the Lok Sabha and the parliaments of the states since independence).

- ^ Report on the Fifth General Elections in India 1971-72. (PDF) Election Commission of India, New Delhi, 1972, accessed on May 27, 2017 .

- ↑ INDIA. (PDF) Interparliamentary Union, accessed on May 11, 2017 (English).

- ↑ a b R. J. Venkateswaran: Indira Gandhi versus Morarji Desai - The real reason for bank nationalization. The Hindu Business Line, February 7, 2000, accessed May 25, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Jaydeb Sarkhel: Financial performance of selected public sector and private sector banks in India during 1994_2004 a comparative study . Ed .: University of Burdwan . 2011, 4th Nationalization of Indian banks and their progress after nationalization (English, handle.net - dissertation, archived at Shodhganga ).

- ^ Currency converter for the past. Retrieved May 25, 2017 (English).

- ^ A b c Brun-Otto Bryde: The bank nationalization in India . In: Constitution and Law in Übersee / Law and Politics in Africa, Asia and LatinAmerica . tape 3 , no. 2 . Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, 1970, p. 195-200 , JSTOR : 43108031 .

- ^ The banks were in detail: 1. Central Bank of India, 2. Bank of Maharashtra, 3. Dena Bank, 4. Punjab National Bank, 5. Syndicate Bank, 6. Canara Bank, 7. Indian Bank, 8. Indian Overseas Bank, 9. Bank of Baroda, 10. Union Bank, 11. Allahabad Bank, 12. United Bank of India, 13. UCO Bank, 14. Bank of India

- ↑ a b WEEKLY SUMMARY: Special Report: India: The World's Largest Democracy To Go To The Polls In March. Central Intelligence Agency , February 19, 1971, accessed May 27, 2017 (CIA report released for publication in 2011).

- ^ Robert L. Hardgrave, Jr .: The Congress in India - Crisis and Split . In: Asian Survey . tape 10 , no. 3 . University of California Press, March 1970, pp. 256-262 , JSTOR : 2642578 (English).

- ^ Mahendra Prasad Singh: Split in a Predominant Party: The Indian National Congress in 1969 . ABHINAV Publications, 1981, ISBN 81-7017-140-7 (the numbers of the fraction sizes given in the literature vary).

- ↑ a b Myron Weiner: The 1971 Elections and the Indian party system . In: Asian Survey . tape 11 , 12, The 1971 Indian Parliamentary Elections: A Symposium. University of California Press, December 1971, pp. 1153-1166 , JSTOR : 2642897 (English).

- ^ Vikas Pandey: A short history of India's political slogans. BBC News, October 9, 2012, accessed May 25, 2017 .

- ↑ Gabriele Venzky: "Indira hatao" - but what now? Zeit online, April 1, 1977, accessed May 25, 2017 .

- ^ Milton Israel: The Indian party system and the 1971 parliamentary elections . In: International Journal . tape 27 , no. 3 . Sage Publications, Ltd. on behalf of the Canadian International Council, 1972, p. 437-447 , JSTOR : 25733950 (English).

- ^ NCB Ray Chaudhury: The Politics of Indias Coalitions . tape 40 , no. 3 . Wiley Online, July 1969, pp. 296–306 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1467-923X.1969.tb00025.x (English).

- ^ Lloyd I. Rudolph: Continuities and Change in Electoral Behavior: The 1971 Parliamentary Election in India . In: Asian Survey . tape 11 , 12, The 1971 Indian Parliamentary Elections: A Symposium. University of California Press, December 1971, pp. 1119-1132 , JSTOR : 2642895 (English).

- ^ Jagdish Raj: The mid-term election in India . tape 17 , no. 3 . Wiley Online, December 1971, pp. 386–391 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1467-8497.1971.tb00502.x (English).

- ^ Biplab Dasgupta: West Bengal Today . In: Social Scientist . tape 1 , no. 8 , March 1973, p. 3-17 , JSTOR : 3516213 (English).

- ↑ Report , p. 37

- ^ Indian Election Commission: Report, pp. 33–36.

- ^ The State of Himachal Pradesh Act, 1970. (PDF) (No longer available online.) Ministry of Justice of India, December 25, 1970, formerly original ; accessed on May 26, 2017 (English). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.