Peter Hagendorf

Peter Hagendorf was a German mercenary of the Thirty Years War . He left an extensive diary , the surviving part of which spans a period of more than 25 years (it begins before 1625 and ends in 1649) and which is considered to be an important testimony to the life of mercenaries at that time. Current research equates him with the Görzker judge and mayor Peter Hagendorf (* 1601/02, † 1679 in Görzke), who from November 1649 is recorded in the local church register with the entry Peter Hagendorf, a soldier .

Peter Hagendorf, the mercenary (before 1625 to 1649)

origin

The name, date and place of birth of the diary writer were initially unknown. Historians assumed that it must have come from the area around Zerbst / Anhalt . He was proficient in reading and writing and was a Protestant. Later research compared existing baptismal registers with childbirth information in the diary and thus determined the name of Peter Hagendorf .

Mercenary life

At the beginning of the 1620s he moved to Italy and, according to his own account, hired himself as a mercenary in the Veltliner War . After his return to Germany he was enlisted in Ulm in 1627 , probably for lack of money, as a private in the infantry regiment of Gottfried Heinrich zu Pappenheim . Then he went to the Musterplatz in the margraviate of Baden , where he married Anna Stadler from Traunstein on May 20, 1627. In the following years he took part in various battles of the Thirty Years War with the Pappenheim Regiment on the side of the Catholic League . Among other things, according to his own statements, in 1631 at the so-called Magdeburg Wedding , where he was seriously wounded near the Hohepfortetor . Because of his reading and writing skills, he was mainly employed in bureaucratic areas and as a judge under military law , was occasionally appointed corporal and was sergeant in a company. He also maintained friendships with executives such as Feldscher Melchert Bordt, Profos Christoff Issel, Lieutenant Colonel Quirinus Müller and Sergeant Benengel Didelin. In 1633 Anna Stadler died in his absence together with her fourth child in the military hospital in Munich. None of the children were older than a year. In the same year he surprisingly met his cousin, master bell founder Adam Ill Iligan , in Dinkelsbühl, who had acquired property there in 1622.

On January 23, 1635, in Pforzheim, he married his second wife, Anna Maria, the daughter of Martin Buchler, probably also a mercenary who was part of the entourage with his family . From June 1641 Johann von Winterscheid took over the Pappenheim regiment. Together with an ensign Nodthaff, Hagendorf was assigned with a group of wounded to Mühlhausen , Thuringia, in November 1641 and stayed there until April 7, 1642. The city archives there named him as the recipient of a pound of meat, two pounds of bread and a liter of beer per day and husband as contribution to the catering. In February 1647 Hagendorf was near a community called Altheim, which was not specified in the diary . In September he gave his son Melchert Christoff, born in 1643, to the schoolmaster of the village church for 10 guilders per year and moved on. He experienced the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 as a garrison soldier in Memmingen . At the time he had covered about 22,500 km through Italy , the Holy Roman Empire , the Spanish Netherlands and the Kingdom of France .

Life after the Peace of Westphalia

In May 1649 Hagendorf brought his son from Altheim and sent him to school at his Memmingen location at the age of five years and nine months. Immediately after the garrison abdicated in September and the negotiated wages of 39 guilders were paid, as well as a deduction , he left Memmingen on September 26, 1649 with his wife and two children. In the same year, his diary was created as a fair copy of his war experiences, the last pages describe his travel route, the last pages of the diary are missing.

Peter Hagendorf in Görzke (1649 - 1679)

In November 1649 a Peter Hagendorf, a soldier, appears as a baptism entry in the church register of the village church in Görzke . A year later he is mentioned in the church register as a judge and mayor . Hagendorf had three sons there, of whom Peter, born on November 9th, 1649, died as a baby. The renovation of the Görzke village church, which was badly damaged by the war, falls in his first year of reign.

progeny

Hagendorf had ten children with Anna Maria Buchler, of whom Melchior Christoph (Melchert Christoff) and Anna Maria, who were born in the war, as well as Andreas and Johannes Leonhard, who were born in Görzke after the war, reached adulthood.

- Melchior Christoph (Melchert Christoff) Hagendorf (born August 6, 1643 in Pforzheim ; † 1721 in Görzke) was judge and church mayor there for 47 years and was one of the largest landowners in the area.

- Anna Maria (born January 5, 1648 in Memmingen; † unknown)

- Andreas Hagendorf (* 1651 Görzke, † probably 1726 in Rädigke ) went to the nearby Rädigke and owned a farm there, which his son Peter Hagendorf junior owned in 1726. took over the Dornberger Hof from 1747 to 1783 .

- Johannes (Hanß) Leonhard, (* June 1654 Görzke; † unknown) becomes master tailor and church council.

Content of the diary

The diary begins at the beginning of the 1620s, the first specific year is 1625. It describes how Hagendorf and his best friend Christian Kresse from Halle marched along Lake Constance through Switzerland to Italy to take part in the Veltliner War . Hagendorf hikes back to Germany via the Gotthard Pass . On the descent, he probably loses cress during a sudden fall in the weather .

In 1627 he was recruited as a mercenary in Ulm due to lack of money. After arriving at the Musterplatz , Hagendorf marries his first wife Anna Stadler from Traunstein , who marches along from this point on. She has four children, none of whom live more than two years. When Anna dies in a Munich hospital due to the consequences of the last birth, Hagendorf is hit hard. Single for two years, he describes u. A. two encounters with women.

"Alhir we Sindt 8 days stilgelehgen, vndt the city plundered, Alhir have I for my booty, a huebsses medelein get vnd 12 tall on money dresses, vndt looking convincing gnug as we have auffbrochen Sindt I heading back to lanshut geschiegket, ..."

"Alhir I also brought out a young medges (?) [In Pforzheim ], but // I let her go back in, which she had to carry out for me, which I was often told that I was aware of this sometimes no weieb ... "

Jan Peters interprets this both as a possible kidnapping and as an encounter with so-called baggage whores . In 1635 Hagendorf married his second wife in Pforzheim, Anna Maria Buchler, the daughter of Martin Buchler, who was marching along with his wife, who, according to Peters, was probably also a mercenary . With her, Hagendorf had six more children during the war.

Hagendorf is involved in the storming of Magdeburg , where he is badly wounded. He fought mainly in the Pappenheim regiment , but is now also forcibly recruited by the Swedes - a common practice in the Thirty Years' War. He gave his son Melchior Christoph (Melchert Christoff) to a schoolmaster when he was growing out of toddlerhood. Melchior Christoph and a later daughter Anna Maria are alive until the end of Hagendorf's notes.

Hagendorf experiences the Peace of Westphalia in Memmingen and sees it ambiguously, as it will rob him of his livelihood and he now has to deal with auxiliary work such as that of a night watchman . He describes how after the war his alcohol addiction increased again and how strange accidents accumulated which, according to Peters, indicate an inability to cope with peace. In May 1649 he picks up his son - without any further explanation in the diary - from the schoolmaster in Altheim , 260 km away . On September 26, 1649, just one day after the abdication of his regiment, on which he had received 39 guilders (three months' salary) compensation, he set off with his son, daughter and wife. He travels north-east at high speed, crossing Babenhausen on September 26th, Günzburg on 27th , Gundelfingen on 28th , Nordlingen on 29th , Öttingen on 30th . Straszb [] rg is recognizable as the last city name , after which the records tear off. It remains to be seen where he will go with his family.

research

Creation and analysis of the diary

In 1648, Hagendorf bought 12 sheets of fine paper from his pay, which he tied together with coarse threads in order to write down his war experiences. The diary was certainly the fair copy of many pieces of paper. The historian Marco von Müller stated in his master’s thesis that notes were verifiably mixed up or lost; in some places parts of the text are not entirely conclusive and sound as if they were reconstructed from memory. The contents were written on (formerly) 192 sheets of paper with mostly twelve straight lines.

The language is unusually cool for the time, with flashes of irony and sarcastic objections.

He shows feelings in things that apparently inspire him, such as nature, mills and architecture. Between the phases of the struggle he describes nature and landscapes verbatim, in detail and with great clarity, and shows a lively interest in the respective inhabitants and their culinary peculiarities. He doesn't glorify war. Hagendorf describes the atrocities that he has to watch, but also causes himself, in a distant manner. Nor does he skimp on self-critical lighting of his own person. This describes his tendency to alcoholism, which he usually has well under control, but which, if he gets through, gets him into trouble, mostly of a financial nature. He sincerely loves his women. He describes his children with reserve while they are still infants. Only when the first, the son Melchior Christoph, reaches toddler age, does his description become warmer and more soulful. When the child begins to be aware of things, he takes care of it with a schoolmaster until the end of the war.

His education, which was unusually high for the time and circumstances at the time, enabled Hagendorf to hold higher posts and positions than other recruits. Because of his reading and writing skills, he was primarily employed in bureaucratic areas and as a judge under military law . He also had some knowledge of Latin, but was not an intellectual. Despite the detailed descriptions, the diary is surprisingly apolitical. Over the years he has not taken any position for any party or religion. His entire focus is on the daily survival of his family and himself.

Find history of the diary

The historian Jan Peters found the records in the West Berlin manuscript index in 1988 during a visit to the Prussian State Library in Berlin . They are there under the signature Ms. germ. Oct. 52 led. The previous owner of the book was the evangelical Berlin pastor and book expert Gottlieb Ernst Schmid (1727–1814), who bequeathed his important book collection to the Berlin State Library in 1803.

At the time it was found, the book was in a battered condition. Water stains, mold and smoke had clogged writing and paper. Of the original 192 sheets, only 176 were preserved. The first 13 and the last three sheets were missing. The surviving part of the diary covers a period of 24 years between 1625 and 1649. Peters translated it into contemporary German and after the fall of the Wall in 1993 he published it for the first time, although the name of the author Peter Hagendorf was only a guess at the time.

Name and origin

The diary does not give the author's name, but does give names and dates of life for children and wives. There were also only a few indirect references to a cousin, an interest in mills and linguistic peculiarities regarding the author's origin. The most important was the naming of the area around Magdeburg as fatherland , or father's country .

"... I have known from herdtzen that the city has so terribly welled the waving of the beautiful city, and that it is my fatherland ..."

The first investigations come from Peters. He looked in chronicles for clues to the author's name, where his children were born and baptized, and where his wives came from. In the diary, Anonymous speaks of his daughter Magreta, who was born on November 3, 1645 in Pappenheim . Peters found the child's name as Anna Marget in the church book of the Lutheran parish office, the mother's name Anna Maria also matches, and the father is named Peter Hagendorf. As a result, he was only able to make general statements about the origin of the name and the spread of the name at that time. He saw evidence of his origins as a miller's son from the Rhineland.

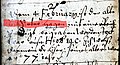

The decisive evidence for the identification of the author was provided in 2004 by Marco von Müller as part of his master's thesis at the Free University of Berlin with Arthur Imhof and Jan Peters. He found an entry in the Mühlhausen city archive under the title Copia Scheinß from December 27, 1641, in which catering services for the period from November 13, 1641 are recorded. They largely coincide with the payments and circumstances noted in the diary. A Peter Hagendorff is named as the recipient in the file. Other sources support this assignment. For example in the first church book (1629–1635) of Engelrod (today part of Lautertal in Vogelsberg ), where the following baptism entry for Eichelhain from August 17, 1630 was found:

"Elisabeth, Peter Hagendorffs, a soldier from Zerbst döchterlein ..."

There was also a reference to the origin from Zerbst, although it was unclear whether the city of Zerbst / Anhalt or the Principality of Anhalt-Zerbst was meant . In addition, there was a contradiction to the previous assumptions. Peters did an investigation in Zerbst and found that several Hagendorfs appeared "at the same time" as Peter Hagendorf in Zerbst (although he does not specify how he defines "simultaneously"). A Jacob Hagendorf, whose children were baptized at the same age as Peter's, he assigned a possible relationship as a brother. He also noticed the origin of the Zerbst Hagendorfs: Buckau near Ziesar , Litzow near Glindow , and also Brandenburg, Magdeburg, Wittenberg and other places in relative proximity .

Remaining after 1679

In 2018, Juliana da Costa José used the methods of operational case analysis to develop a profile of Peter Hagendorf and based on this the thesis that he could have come from the Hohen Fläming and went back there. She turned to Müller and he informed the historian Hans Medick . Together with handwriting expert Claudia Minuth, they found entries in Görzk church registers from 1649. Apparently, Hagendorf arrived with his family in Görzke as early as autumn 1649, because from November 9th “Peter Hagendorf, a soldier” and “Anna Maria Hagendorf, wife of Peter Hagendorf “as well as descendants of the two named several times. Müller and Medick analyzed the alleged way back in terms of plausibility and made historical considerations on the reason for return, for example, penal ordinances and resettlement measures that ordered members of the army and refugees dispersed in Saxony-Anhalt to return to their places of origin in order to repopulate the orphaned regions. The church register entries could be confirmed by these investigations.

On February 4th jul. / February 14, 1679 greg. old M: Peter Hagen was buried in Görzke at the age of 77. Medick concludes from the currently available data that the burial entry mentioned is that of the soldier Peter Hagendorf , who verifiably had his son of the same name baptized there in November 1649. According to Medick, there is evidence that this Peter Hagendorf was elected “Mayor and Judge”. Calculated backwards, the year of birth 1601 or 1602 would come into question.

Films and documentaries

- The Thirty Years War (Part 1) - Of Generals, Mercenaries and Careerists. Documentary, Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR), Germany 2011. With Matthias Klösel as Peter Hagendorf.

- Believe, live, die. Documentary, ARD (BR, MDR, SWR) and ORF, Germany 2018. A film by Stefan Ludwig with Robert Zimmermann as Peter Hagendorf.

- Terra X : The Thirty Years War (Part 1) - Diaries of Survival. Documentary, ZDF, Germany 2018. A film by Ingo Helm and Volker Schmidt-Sondermann with Philip Hagmann as Peter Hagendorf.

- The Iron Age - Live and Love in the Thirty Years War. Six-part docu-drama, ZDF / Arte, Germany 2018. Producer: Gunnar Dedio , script: Yury Winterberg , with Jan Hasenfuss as Peter Hagendorf.

literature

(in chronological order)

- Jan Peters (ed.): A mercenary life in the Thirty Years War. A source on social history. (= Personal testimonies of modern times. Sources and representations on social and empirical history, volume 1). Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-05-001008-8 .

- Peter Burschel : Heaven and Hell. A mercenary, his diary and the rules of war. In: Benigna von Krusenstjern , Hans Medick (Hrsg.): Between everyday life and catastrophe. The Thirty Years War up close. (= Publications of the Max Planck Institute for History, Volume 148). 2nd Edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-525-35463-0 , pp. 181-194.

- Luise Wagner-Roos, Reinhard Bar: Between heaven and hell - memories of a mercenary life. In: Hans-Christian Huf (ed.): With God's blessing in hell - The Thirty Years War. Ullstein-Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 978-3-548-60500-5 , pp. 104-127.

- Marco von Müller: The Life of a Mercenary in the Thirty Years War . Master's thesis at the Friedrich Meinecke Institute , 2005 ( PDF ; 5.6 MB).

- Jan Peters (Ed.): Peter Hagendorf - Diary of a mercenary from the Thirty Years War. (= Rulership and social systems in the early modern times, volume 14). V & R Unipress, Göttingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-89971-993-2 .

- Christian Pantle : The Thirty Years War. When Germany was on fire. About robbery, murder and looting and humanity in war. Propylaen Ullstein Buchverlage GmbH, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-549-07443-5 .

- Hans Medick : The Thirty Years War - Evidence of Life with Violence, Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-8353-3248-5 (chapter “The perpetrator perspective of a mercenary”, pp. 113–115; “The return of Peter Hagendorf ”, pp. 115–122;“ Survival of a mercenary and his family in war ”, pp. 134–141;“ Siege ”, pp. 197–198;“ Massaker ”, pp. 219–222).

Web links

- Digitized of the Berlin manuscript Ms. germ. Oct. 52

- Kathrin Halfwassen: A life for death. In: Zeit Online , January 5, 2018.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Jan Peters: Peter Hagendorf - Diary of a mercenary from the Thirty Years War. 2012, Chapter: State of research and topics in the diary, pp. 199ff

- ↑ Gustav Hey , Karl Schulze: The settlements in Anhalt. Villages and desert areas with an explanation of their names . Orphanage, Halle 1905.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Marco von Müller: The life of a mercenary in the Thirty Years War . Master's thesis at the Friedrich Meinecke Institute, Bonn 2005 ( mvonmueller.de [PDF]).

- ^ Sigrid Thurm, Franz Dambeck (ed.): German Bell Atlas Volume 3 - Middle Franconia . Deutscher Kunstverlag Munich, 1973, ISBN 978-3-422-00543-3 , p. 99 note 188 .

- ↑ a b Hans Medick: The Thirty Years War - Testimonies of Life with Violence . 3. Edition. Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-8353-3248-5 , pp. 113 ff .

- ↑ Claudia Jarzebowski: Childhood and Emotion: Children and Their Worlds in the European Early Modern Era . Walter de Gruyter, 2018, ISBN 978-3-11-046891-5 , p. 76 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b c d e Marco von Müller: Peter Hagendorf returns home ; Hans Medick : The Thirty Years War - Evidence of Life with Violence. Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-8353-3248-5 , pp. 118/119.

- ↑ a b c Church records Görzke 17th to 19th centuries, translated by Claudia Minuth, Parish Office Elbe-Fläming , on May 28, 2018, report by Hans Medick, May 31, 2018.

- ↑ Bernd Moritz, Gerd-Christian Treutler: The farms of Rädigke, Hoher Fläming . In: Brandenburgisches Genealogisches Jahrbuch . tape 5 , 2011, p. 51 ff . ( bggroteradler.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Diary, pp. 2–8.

- ↑ Diary, pp. 10–12.

- ↑ Diary, pp. 14–38.

- ↑ Diary, p. 44.

- ↑ Diary, p. 50.

- ↑ Jan Peters: Peter Hagendorf - Diary of a mercenary from the Thirty Years War. 2012, Chapter: Lifestyle and Soldier Culture, p. 169.

- ↑ Diary, pp. 38–50.

- ↑ Diary, pp. 53 ff.

- ↑ Diary, pp. 23-27.

- ↑ Diary pp. 39–48.

- ↑ Diary, p. 167.

- ↑ Diary pp. 173–176.

- ↑ Master's thesis M. v. Müller ff.

- ↑ Diary, pp. 25ff

- ^ Ortwein, church books Engelrod , p. 184.

- ^ Friedrich J. Ortwein (ed.): The church books Engelrod 1629–1698 . Hanover and Cologne 1993/2006, p. 4ff.

- ↑ Michael Kaiser: Review of: Jan Peters (ed.): Peter Hagendorf - Diary of a mercenary from the Thirty Years War , Göttingen: V&R unipress 2012, in: sehepunkte 13 (2013), No. 4 [April 15, 2013]

- ↑ Eckhard Oelke : About the repopulation of today's Saxony-Anhalt after the Thirty Years War (1618–1648). In: Hercynia . New Volume 38, 2005, pp. 5–24 (PDF) .

- ^ Christian Pantle: The Thirty Years War. When Germany was on fire. About robbery, murder and looting and humanity in war . 7th edition. Ullstein, 2019, ISBN 978-3-548-06058-3 ( google.de ).

- ↑ Hans Medick: The Thirty Years' War - testimonies to life with violence . 3. Edition. Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-8353-3248-5 , pp. Note 55 ( google.de ).

- ↑ The Thirty Years' War (Part 1) - Of Generals, Mercenaries and Careerists. In: Fernsehserien.de. Retrieved May 30, 2018 .

- ↑ Toppler actor Klösel plays the leading role in BR film. In: Nordbayern.de. January 7, 2011, accessed May 30, 2018 .

- ↑ Believe, Live, Die. In: DasErste.de. Retrieved May 30, 2018 .

- ↑ Terra X: The Thirty Years War (1/2) - Diaries of Survival. In: ZDF.de. Retrieved September 26, 2018 .

- ↑ The Iron Age - Live and Love in the Thirty Years' War. In: NICCC.de. Retrieved September 4, 2018 .

- ↑ The Iron Age - Live and Love in the Thirty Years' War. In: Fernsehserien.de. Retrieved September 26, 2018 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hagendorf, Peter |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Mercenary in the Thirty Years War |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1600 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | unsure: Zerbst |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1679 |

| Place of death | Görzke |