Prisoner of war

A prisoner of war is a combatant (generally a soldier ) or a specific non-combatant who is captured by opposing military during an armed conflict .

Today's international law

Word usage

For example, prisoners of war are marked with the abbreviation POW for “Prisoner of War” in the English-speaking countries and with ВП for “военнопленный” (= WP - wojennoplennij ) on their clothing. In legal and diplomatic parlance, the term hors de combat (French for “incapable of fighting” or “incapacitated”) is customary and includes both prisoners of war and wounded soldiers.

definition

For the treatment of prisoners of war, the international legal regulations of the Hague Land Warfare Act of 1907 (Articles 4 to 20) and III. 1949 Geneva Convention (one of the four Geneva Conventions ). In order to be considered a prisoner of war, according to the Geneva Conventions, the person concerned must be an official participant in a conflict or a member of a military command structure and be recognizable as such. This also includes people who are not military personnel but who work for the armed forces (see also military service providers ). In most cases, the police and paramilitary organizations are not considered to be involved, but if the state concerned so wishes, it must inform the war opponent.

For the acceptance of the prisoner of war status, it is important to wear a uniform or identification marks that identify the person involved. If those involved cannot be distinguished from civilians, if their weapons are concealed or if they wear hostile uniforms, they lose this status. Prisoner-of-war status is also applied to rebels who fight in uniforms and with openly carried weapons and are involved in command structures. Prisoner of war status is not applied to bombers and members of international and national terrorist organizations.

In case of doubt, all other persons who have carried out acts of war are to be treated as prisoners of war until the competent courts have decided on their status. The prisoners of war are subject to the violence of the detaining state. They are not under the control of the people and units who have captured them. Individuals are not allowed to make decisions about prisoners of war, even if they have obviously violated the rules of warfare.

Medical personnel , even if they carry a handgun for self-defense , as well as religious personnel do not count as combatants. They are therefore not formally prisoners of war even in captivity, but enjoy the same protection. They are allowed to continue their work and are to be supported in this. Paramedics may only be withheld by the detaining state for as long as they are needed to care for their wounded compatriots.

A spy who secretly and without participating in acts of war has obtained information in the territory of the enemy and has returned to the sphere of control of his war party may not be punished after his capture and is entitled to treatment as a prisoner of war.

Rights and duties of prisoners of war

Prisoners of war are not prisoners of war , but security prisoners who are subject to the Detaining State as state prisoners . The Detaining State is responsible for the treatment. Inhuman and degrading treatment and reprisals are prohibited.

Combatants who hold up their arms, are defenseless or otherwise unable to fight or defend themselves, or who surrender, may not be fought. You can be disarmed and captured.

Prisoners of war are to be brought out of danger as soon as possible. If they cannot be removed due to the combat conditions, they are to be released. Implementable measures for your safety must be taken.

POWs are required to name , first name , date of birth, rank and personal identification number to call. Military equipment and weapons are to be taken from them. Personal items including helmets, NBC protective equipment, food, clothing, rank and nationality symbols and awards may be kept. Money and valuables may only be withdrawn on receipt of an officer's order, which must, however, be returned upon discharge.

The detaining state can use team ranks for non-military work. Officers are not allowed to work, but must be given preferential treatment. The agreement itself only distinguishes between men and officers; NCOs below a certain rank ( ensign , corresponding to the German ranks Sergeant and Boatswain) are considered to be crews. Work that is harmful to health or particularly dangerous work may only be assigned to volunteers.

If an escaping prisoner of war does not use violence against persons (even if it does so again), attempts to escape may only be punished by discipline.

The violation of these rights occurs in almost every war and usually provokes similar attacks on the other side. Particularly serious violations of the law, which often affect a large number of opposing army members, can be classified as war crimes.

Disregard for the rights of prisoners of war

Most warring parties do not adhere to the Geneva Conventions on the Treatment of Prisoners of War on many points. In addition to the frequent disregard of the Geneva documents during a war or a conflict after the end of the conflict, many of these soldiers are often retained as “spoils of war”. They are used as a deposit in z. B. sometimes secret negotiations are used to wrest concessions or payments from the opposing parties.

history

The victor in a battle wielded the lives and possessions of those who were at his mercy. There was no separation between combatants and civilians. The fate of the vanquished ranged from being slaughtered on the battlefield to mutilation to kidnapping or being forced to serve as an army officer. But a simple release was also possible. A common fate was enslavement. Even at the beginning of the written tradition, wars are reported that were fought for the purpose of procuring slaves . Assyrian sources from the time of Hammurabi report the ransom of enslaved prisoners of war.

European development until 1907

In ancient Greece, too, prisoners of war had no special legal status. The general legal conception was that the strong should and should rule over the weaker. The normal procedure was to sell or redeem the captured enemy warriors. Thucydides reports in several places about prisoners of war in the Peloponnesian War . 421 BC Sparta offered peace on a pre-war basis in order to get back the 120 Spartians (full citizens) who had surrendered in the Battle of Sphakteria . The survivors of the Sicilian expedition were born in 413 BC. In the quarries of Syracuse, where they perished miserably. About 3,000 prisoners were taken after the Battle of Aigospotamoi . After a criminal court, Lysandros had all of the full citizens of Athens executed because they had "started illegal acts among the Hellenes."

The same was done in Roman culture. The "spoils of war man" was an important economic factor. The prisoners of war on display formed an essential element on the triumphal procession of the victorious generals. In the civil wars , the legionaries of the defeated party were often pardoned or incorporated into their own ranks. On the other hand, z. B. 71 v. All 6000 prisoners of the Spartacus uprising were crucified along the Via Appia .

A change in the status of prisoners of war occurred when the Third Lateran Council banned the sale of Christians into enslavement in 1179. As a result, it was no longer profitable to take many prisoners: Captive infantry were killed on the battlefield or simply let go. A lucrative trade developed around the ransom of higher-ranking prisoners of war. A famous example is the capture of Richard the Lionheart in 1192.

At the time of the great mercenary armies in the late Middle Ages and early modern times, prisoners were often exchanged for one another on the battlefield. There were certain quotas for officers or generals in relation to foot soldiers. It was also common practice to release prisoners of war if they vowed not to intervene in the conflict.

The mass conscripts for military service after the French Revolution meant that hundreds of thousands of prisoners of war were now incurred and had to be cared for. At the same time, the view prevailed that wars were primarily a matter of the state and that captured soldiers had certain rights. In the Franco-Prussian War , the 8,000 Germans faced more than 400,000 French prisoners of war, so an exchange was out of the question. Theodor Fontane describes his experiences as a German prisoner of war in POW . Experienced in 1870 and in his notebook. The problems with interning and caring for these masses were a major factor behind the creation of the Hague Land Warfare Regulations .

However, the international legal practices of Europe were not necessarily applied in colonial wars. There continued to be real genocides on the part of the imperial powers .

First World War

During the First World War , around eight million soldiers surrendered to opposing armed forces and were prisoners of war at the end of the war. As a rule, all participating nations in the European theater of war adhered to the Hague Agreement with regard to the section of captivity . Usually prisoners of war had a greater chance of survival than their non-captured comrades. The bulk of prisoners of war was incurred when larger units had to lay down their arms. Examples are the 95,000 Russian soldiers captured after the Battle of Tannenberg (1914) or the 325,000 members of the Austro- Hungarian Army after the Brusilov offensive in 1916.

Germany held a total of 2.5 million soldiers prisoner, Russia 2.9 (including about 160,000 German and 2.1 million Austro-Hungarian soldiers), Great Britain , France and the USA 768,000. Conditions in the prisoner-of-war camps during the war were sometimes significantly better than in the Second World War. This was achieved through the efforts of the International Red Cross and observers from neutral countries.

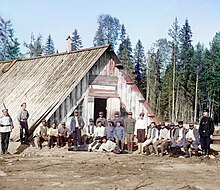

In Russia, the situation in the prisoner-of-war camps, which were often in inhospitable areas of Siberia and Central Asia , was particularly bad. Of the approximately 2.2 million soldiers of the Central Powers in Russian captivity, about 25% died. The big typhus epidemics in the first winters of the war and the construction of the Murman Railway are notorious .

The supply situation in the German camps was poor, which was due to the general shortage of food during the war , but the mortality rate was only 5%.

The Ottoman Empire often treated its prisoners of war badly. In April 1916, for example, 11,800 British soldiers, most of them Indians , surrendered in the Battle of Kut . 4,250 of them died of starvation within a few weeks.

Prisoners of war were used in agriculture and industry and were an important economic factor during the war.

In addition to soldiers, large numbers of civilians from enemy states were interned or deported to Siberia in Russia during the First World War.

Second World War

-

POW camp

- German POW camps: main camps (StaLag or OffLag)

- List of Wehrmacht POW camps

After the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War , Emperor Hirohito issued an explicit order in his directive of August 5, 1937 not to adhere to the Hague Agreement when treating Chinese prisoners of war. The Japanese Empire , which had never signed the Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War , basically took hardly any prisoners in China. Chinese soldiers who tried to surrender were usually shot or killed after capture. Of the millions of Chinese soldiers and partisans who tried to surrender to the Imperial Japanese Army , only 56 prisoners survived the war.

Chinese, American, Dutch, British, Australian , Indian , New Zealand, and Canadian prisoners of war were often victims of torture, deadly forced labor, death marches, and human attempts . Many of the prisoners starved to death and the International Red Cross was denied access to the camps. Well-known examples are the Death Railway and the Bataan Death March . The death rate among Allied prisoners of war was 27.1%.

Soviet prisoners of war were treated extremely badly by the German Reich . They suffered from hunger, cold, forced labor, and abuse. Gestapo commandos searched the ranks of the prisoners for Jews , state officials and other "intolerable" or "dangerous" individuals as well as Soviet commissioners who had survived the commissioner's order and took them to extermination camps , where they were usually killed immediately ( war crimes ). A total of between 140,000 and 500,000 Soviet prisoners of war died in concentration camps , most of them shot or gassed. Of the 5.7 million Soviet soldiers who were in German captivity, 3.3 million did not survive the war, which corresponds to 57%. 500,000 Soviet prisoners were freed by the Red Army during the war. 930,000 were released from camps after the war. Numerous Soviet cemeteries (war graves) in Germany document the high number of Soviet prisoners of war and forced laborers who perished in Germany .

The treatment of West Allied prisoners of war was generally good, and the Geneva Convention was followed. Of the 232,000 US, British, Canadian and other soldiers, 8,348 did not survive the war, which is 3.5%. However, the OKW established a “racial separation”. Colored soldiers from the colonial troops of Great Britain, France and Belgium often suffered ill-treatment and inadequate care and feared arbitrary killings. While in 1940 dismissed the majority of the French colonial soldiers or moved to France were in III A main camp in Luckenwalde around 500 men for " tropical medicine study purposes retained" which partly as extras in propaganda films of the UFA as Germanin - The story of a colonial fact were used . Her further fate is unclear.

After the Red Army marched into Poland in 1939, 240,000 Polish soldiers were taken prisoner by the Soviets, of whom only 82,000 survived the war, bringing the death rate to 66%. 20,000 prisoners of war and civilians were killed in the Katyn massacre .

According to some sources, the Soviet Union captured 3.5 million Axis soldiers (including Japanese soldiers in Manchuria), of whom around one million died. A special example is the Battle of Stalingrad , in which 91,000 German soldiers surrendered. Only 5000 survived captivity. The Italian soldiers who were prisoners of war, the mortality rate was also very high. Of the 54,000 prisoners, 84.5% died.

The United States made over 700,000 prisoners of war available to the French. France forced around 50,000 into high-risk forced labor as deminers. Finally, in the spring of 1946, the ICRC was allowed to hold visits and provide limited amounts of food to prisoners of war in the American Zone . Almost all former German soldiers returned to Germany from western captivity after the surrender by 1948. Captivity in the Soviet Union usually lasted three years; But it could also last up to 10 or more years - for example for Stalingrad fighters.

In 1955, Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer achieved a great political success by bringing about the release of the last prisoners , some of whom had been sentenced to prison terms of up to 25 years by Soviet courts for various reasons.

As part of Operation Keelhaul , Soviet prisoners of war were sent back to the Soviet Union by the British and the Americans - often against their will - because the repatriation of the prisoners of war had been decided at the Yalta Conference in January 1945. In the 1992 book Soldiers of Misfortune , the authors claim that contrary to the agreement, the Soviet Union withheld approximately 20,000 US and approximately 30,000 Commonwealth soldiers and that the US government was aware of this.

today

Also after the world wars there were again prisoners of war, especially in the course of the Korean War , the Vietnam War , the Bangladesh War , the Gulf Wars and the Yugoslav Wars . In the Vietnam War, for example, thousands of US soldiers were captured in the Hỏa Lò prison , some of whom were only gradually released (e.g. as part of Operation Homecoming ). War crimes also occurred again. So were z. B. In 1950 in the Korean War at the Hill 303 massacre, 41 American prisoners of war were murdered. But the USA itself is also accused of serious human rights violations, for example in Abu Ghuraib prison , and against so-called " unlawful combatants " in the prison camp at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base .

Prisoner of War (POW) is the status designation for soldiers in enemy captivity in Anglo-American usage. The abbreviation "POW" is used alongside the abbreviations "WIA" ( Wounded in Action ), "MIA" ( Missing in Action ) and "KIA" ( Killed in Action ) in loss lists of Anglo-American armed forces. You will be remembered with the POW / MIA flag .

Movies

- Dirk Pohlmann (director): spoils of war man - how governments betray their soldiers. Documentation, Germany, 2006, 89 min. (Also on the delayed or dubious repatriation of US POWs and other Western Allies from German camps by the Red Army after the end of the war (WW2, Odessa) and on the situation in the Vietnam War)

literature

- The bibliographical database RussGUS records :

- 87 publications about the Soviet prisoners of war in Germany (search for forms / subject notations: 12.3.4.5.3.4.7.1)

- 137 publications about German prisoners of war in the USSR (search for forms / subject notations: 12.3.4.5.3.4.7.2)

- Martin Albrecht, Helga Radau: Stalag Luft I in Barth. British and American prisoners of war in Pomerania 1940 to 1945. Thomas Helms Verlag Schwerin 2012. ISBN 978-3-940207-70-8

- Günter Bischof, Stefan Karner, Barbara Stelzl-Marx (ed.): Prisoners of War of the Second World War. Capture, camp life, return. R. Oldenbourg-Verlag, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-7029-0537-5 . (Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57818-9 )

- Roger Devaux: Treize Qu'ils Etaient - The life of the French prisoners of war with the farmers in Lower Bavaria during the Second World War. In: Treize Qu'ils Etaient. ISBN 2-916062-51-3 .

- Jörg Echternkamp (Ed.): The German War Society 1939–1945. The German Reich and the Second World War . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Volume 9 in two half-volumes, Munich 2004/05, ISBN 3-421-06528-4 . In particular, in vol. 2, the chapters by Mark Spoerer, Ela Hornung, Ernst Langthaler, Sabine Schweitzer, Oliver Rathkolb: Forced laborers, prisoners of war and prisoners in German industry and agriculture.

- Edda Engelke: Lower Austrians in Soviet captivity during and after the Second World War. Self-published by the Association for the Promotion of Research on Consequences after Conflicts and Wars, Graz 1998, ISBN 3-901661-02-6 .

- Andreas Hilger : German prisoners of war in the Soviet Union 1941–1956. Prisoner of War Policy, Everyday Camp Life and Memory. Klartext-Verlag, March 2000, ISBN 3-88474-857-2 .

- Andreas Hilger: Soviet justice and war crimes. Documents on the convictions of German prisoners of war, 1941–1949 . Evidence, summary. In: ifz. Issue 3/06.

- Rolf Keller : Soviet prisoners of war in the German Reich 1941/42. Treatment and labor input between the politics of extermination and the requirements of the war economy, Göttingen 2011. ISBN 978-3-8353-0989-0 . Reviews: H-Soz-u-Kult February 9, 2012, www.kulturthemen.de February 9, 2012

- Guido Knopp: The prisoners. C. Bertelsmann Verlag, 2003.

- Reinhard Nachtigal: Russia and its Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war (1914–1918). Greiner, Remshalden 2003, ISBN 3-935383-27-4 .

- Jobst von Nordheim: Lost Years. In: A flag junior's memories of the Russian captivity of war and accounting for national (social) ism. Baltica Verlag, Flensburg 2000, ISBN 3-934097-09-X .

- Jochen Oltmer (Ed.): Prisoners of War in Europe during the First World War. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn, u. a. 2006, ISBN 3-506-72927-6 . (= War in History [KRiG], Vol. 24.)

- Rüdiger Overmans : The prisoner-of-war policy of the German Reich 1939 to 1945. In: The German Reich and the Second World War. Vol. 9/2. Munich 2005.

- Rüdiger Overmans (ed.): In the hand of the enemy: Captivity from antiquity to the Second World War. Böhlau, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-412-14998-5 .

- Rüdiger Overmans: Soldiers behind barbed wire. German prisoners of war of the Second World War. Ullstein Tb., 2002.

- Dankward Sidow: “Ruki werch!” (German: hands up!) - Personal experience as a soldier and prisoner of war in Soviet custody from 1944–1949, with Soviet prisoner-of-war personnel files, camp plans, complete correspondence and Soviet official reports with photos about camp 126 - Nikolayev to the responsible ministries in Kiev and Moscow. Self-published in Hamburg.

- Christian Streit: No comrades. The Wehrmacht and the Soviet prisoners of war 1941–1945. DVA, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-421-01883-9 .

- Philippe Sunou: Les Prisonniers de guerre allemands en Belgique et la Bataille du Charbon 1945–1947. Musée Royal de l'Armée , Brussels 1980. (French)

- Wolfgang Stadler: Hope - homecoming. At 17 to the front - at 19 behind barbed wire. Swing-Druck, Colditz 2000, ISBN 3-9807514-0-6 .

- Georg Wurzer: The prisoners of war of the Central Powers in Russia in the First World War. V&R unipress Verlag, ISBN 3-89971-241-2 . (on-line)

- Yücel Yanıkdağ: “Ottoman Prisoners of War in Russia, 1914-22”, Journal of Contemporary History 34/1 (Jan. 1999), pp. 69-85. (English)

- Yücel Yanıkdağ: Healing the Nation: Prisoners of War, Medicine, and Nationalism in Turkey, 1914–1939 . Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-7486-6578-5 (English).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Karl Doehring: Völkerrecht. Heidelberg 1999, ISBN 3-8114-5499-4 .

- ↑ Article 46, Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions of 1949.

- ↑ Erich Ebeling: Reallexikon der Assyriologie. Volume 7, ISBN 978-3-11-010437-0 .

- ↑ Xenophon: Hellenika

- ^ Theodor Fontane: Notebooks. Genetically critical and annotated edition. Edited by Gabriele Radecke. Göttingen 2019. Notebook D06: Theater of War 1870

- ^ Geo G. Phillimore, Hugh HL Bellot: Treatment of Prisoners of War. In: Transactions of the Grotius Society. Vol. 5, (1919), pp. 47-64.

- ↑ http://tobias-lib.uni-tuebingen.de/volltexte/2001/207/pdf/diss_wurzer.pdf , p. 22.

- ^ Robert B. Kane, Peter Loewenberg: Disobedience and Conspiracy in the German Army, 1918-1945. McFarland , 2008, ISBN 978-0-7864-3744-3 , p. 240.

- ↑ Richard B. Speed, III. Prisoners, Diplomats and the Great War: A Study in the Diplomacy of Captivity. (1990); Ferguson, The Pity of War. (1999) Ch 13; Desmond Morton, Silent Battle: Canadian Prisoners of War in Germany, 1914-1919. 1992.

- ^ British National Archives: The Mesopotamia campaign.

- ↑ Akira Fujiwara: Nitchû Sensô ni Okeru Horyo Gyakusatsu. Kikan Sensô Sekinin Kenkyû 9, 1995, p. 22.

- ↑ Tanaka, ibid., Herbert Bix: Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. 2001, p. 360.

- ^ Japanese Atrocities in the Philippines. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS)

- ^ Gavin Dawes: Prisoners of the Japanese: POWs of World War II in the Pacific. ISBN 0-688-14370-9 .

- ↑ Yuki Tanaka: Hidden Horrors. 1996, pp. 2, 3.

- ^ No Mercy: The German Army's Treatment of Soviet Prisoners of War. ( Memento from June 3, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ The treatment of Soviet POWs: Starvation, disease, and shootings, June 1941 - January 1942. USHMM.

- ^ Christian Streit: No comrades. The Wehrmacht and the Soviet prisoners of war 1941–1945. DVA, Stuttgart 1978, p. 10.

- ↑ Soviet Prisoners of War: Forgotten Nazi Victims of World War II. ( Memento of March 30, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Michael Burleigh : The Third Reich — A New History . Hill and Wang, New York 2000 ,, ISBN 0-8090-9325-1 , pp. 512-513.

- ↑ Uwe Mai, Uwe: Prisoners of War in Brandenburg: Stalag IIIA in Luckenwalde 1939–1945, Berlin 1999, pp. 147–156.

- ↑ Michael Hope: Polish deportees in the Soviet Union. ( Memento from February 16, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Stéphane Courtois, Mark Kramer: Livre noir du Communisme: crimes, terreur, répression. Harvard University Press , 1999, ISBN 0-674-07608-7 , p. 209.

- ^ German POWs and the Art of Survival. ( Memento from December 19, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ German POWs in Allied Hands — World War II. ( Memento from April 12, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Forced labor as a mine clearer - "Rudi was completely riddled with holes". In: one day . August 27, 2008, Der Spiegel . 35/2008.

- ↑ Staff: ICRC in WW II: German prisoners of war in Allied hands. February 2, 2005.

- ↑ James D. Sanders, Mark A. Sauter, R. Cort Kirkwood: Soldiers Of Misfortune; Washington's Secret Betrayal of American POWs in the Soviet Union. National Press Books, 1992.