Rudolf Diesel

Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel (born March 18, 1858 in Paris , † September 29, 1913 , last seen alive on board the ferry Dresden on the English Channel during the crossing to England) was a German engineer and the inventor of the diesel engine .

Life

Childhood in Paris

Rudolf Diesel was the second child of the trained bookbinder and later leather goods manufacturer Theodor Diesel, who had left his hometown Augsburg in 1848 and moved to Paris because there he had met his future wife Elise Strobel. She was the daughter of a Nuremberg belt master and haberdashery merchant who, after the closure of her father's business in Paris, had made her way as housekeeper and companion.

Diesel spent his childhood and youth in Paris and the surrounding area until 1870. At the age of 12 he was awarded a bronze medal by the Société pour l'instruction élémentaire in 1870 for outstanding achievements .

After the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War , the expulsion of all non-French people from France was ordered on August 28, 1870 . Therefore, the Diesel family left Paris on September 4th or 5th for London .

Training in Augsburg

On November 1, 1870, Rudolf traveled alone from London to Augsburg , the birthplace of his father. His uncle Christoph Barnickel was a professor at the Augsburg Royal District Industrial School. Barnickel and his wife Betty took him in as a foster child for five years.

Rudolf Diesel went to his uncle's trade school as a student. In 1872 he decided to become a "mechanic" (engineer). In 1873 he graduated from the trade school as the best. Then he attended the recently opened industrial school in the same building, a forerunner of the Augsburg University of Applied Sciences . In the summer of 1875 he also finished this training as a Primus.

Studied in Munich

Rudolf Diesel began his studies in 1875 at the Polytechnic School in Munich , which was called the Royal Bavarian Technical University of Munich from 1877 (today Technical University of Munich ). At that time he became a member of the “Sketch Association of the Mechanical-Technical Department of the Royal Polytechnic in Munich”, which later changed into the student association AMIV (Academic Mechanical Engineering Association) and awarded Diesel an honorary membership. In 1877 the parents sold their business in Paris and moved to Munich. Rudolf Diesel moved in with them. In 1878 he attended lectures from Carl Linde .

Because of typhoid fever, Diesel was unable to complete his studies in 1879. In October he gained experience in the machine factory of the Sulzer brothers in Winterthur producing Carl Linde's ice machines . In January 1880, he took the final exam at the Technical University of Munich with the best performance since the establishment of the institution.

Work in the ice cream factory in Paris

In March 1880, Diesel traveled to Paris to found the Linde ice cream factory and joined the company as a volunteer. The next year he became director of the ice cream factory. In September his first patent was filed for a process for making clear ice in bottles. In 1883 Diesel built a clear ice plant for the Paris ice cream factory.

Starting a family

In May 1883, Rudolf Diesel got engaged to Martha Bottle, the daughter of a notary from Remscheid , whom he had met the year before in Paris. The wedding took place in Munich in November. The first son Rudolf was born in 1884, the daughter Hedy in 1885, and the second son Eugen in 1889 .

After Carl Linde offered him a job in Berlin , Diesel returned to Germany in February 1890. He was elected to the board of the newly founded stock corporation for market and cooling halls .

Development of the diesel engine

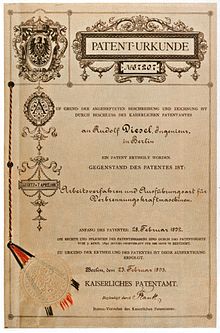

On February 27, 1892, Diesel registered a patent for a new efficient heat engine at the Imperial Patent Office in Berlin , which he received on February 23, 1893 under the number DRP 67 207 with the subject "Working method and design for internal combustion engines".

However, this first patent does not describe today's diesel principle, but Diesel's initial idea. This consisted of an "ideal heat engine" according to the theory of the ideal cycle of Sadi Carnot . Against the background of the then prevailing state of the art, the feasibility from a practical point of view was questioned. In particular, the high pressures first calculated by Diesel were not considered controllable. To exhaust what was just believed to be possible and to be able to convince influential sponsors was later seen as a “triumph of theory”.

Diesel was granted a second patent for a modification of this original Carnot process with the equal pressure process (November 29, 1893, DRP 82 168). The principle had already been patented by Herbert Akroyd Stuart of England in 1890; his working machine was built in July 1892 by Richard Hornsby & Sons in Grantham .

Diesel used kerosene for his first experiments, but it didn't work. He therefore initially switched to gasoline in order to achieve ignition at all. The fuel was atomized via a converted carburetor and blown into the combustion chamber together with air under high pressure. A complicated and fragile compressor, the so-called injection machine, was used to generate pressure. One of the problems was that the pressurized mixture could not get too hot, otherwise the gasoline would already partially burn in the pipe - which also happened. So it was compressed and cooled in several stages. But then the air heated by compression in the combustion chamber still had to be able to ignite the blown (extremely rich) mixture.

Through his book Theory and Construction of a Rational Heat Engine to Replace Steam Engines and the Today's Internal Combustion Engines (1893), published by Julius Springer , he came into contact with Heinrich von Buz , the general director of the Augsburg machine factory, which later (1908) became the MAN company AG emerged. With financial support from the company Friedrich Krupp Rudolf Diesel developed the there from 1893 diesel engine . On August 10, 1893, the engine ignited for the first time, and on February 17, 1894, it ran for the first time on its own.

In 1897 the first working model of this engine was ready. It ran with an efficiency of 26.2 percent. Without the engineers from MAN and the financial support, Diesel would not have brought the engine to series production. The planned six-month development period had turned into four long years with numerous setbacks. Diesel's biggest problem was that the technology developed at MAN no longer corresponded to his patent.

Start of engine production

On January 1st, 1898, the Augsburg diesel engine factory was founded. On September 17, 1898, the General Society for Diesel Engines was founded. In the same year, the first diesel engines were built in the United States and the first Sulzer diesel engine in Switzerland. Because of chronic exhaustion, Diesel stayed in the Neuwittelsbach sanatorium near Munich in autumn 1898.

The Diesel Engine Company was founded in London in autumn 1900 . The diesel engine was awarded the Grand Prix at the World Exhibition in Paris . In the spring of 1901, Diesel and his family moved into a newly built villa at Maria-Theresia-Strasse 32 in Munich.

From around 1900 Rudolf Diesel also worked temporarily in the Leobersdorfer machine factory in Austria to introduce the diesel engine. Five years later, Austria's first diesel engines were built in Leobersdorf. The first motor ships with diesel engines were built in 1903. In 1908 the first small diesel engine was built.

Years of patent litigation ruined Diesel's health. It also went downhill economically - the ingenious engineer had no talent as a businessman. In 1911 the Augsburg diesel engine factory was dissolved again. In the same year, the Diesel Motor Company of America became the Busch-Sulzer Bros. Diesel Engine Company through a joint venture .

In 1910, the research ship Fram was the first ocean-going ship to have a diesel engine. With the Selandia , the first ocean-going diesel motor cargo ship was launched in Copenhagen in 1912. In the same year there was the first diesel locomotive .

Until recently, Diesel worked tirelessly to find new fields of application for his invention, e.g. B. in inland navigation on the major rivers in the African colonies. In an article published in 1912 in the monthly journal Technology and Economics of the Association of German Engineers (VDI) and almost word for word and at the same time in Prometheus, he highlighted the advantages of the diesel engine over other types of drive: The good availability of mineral oil on all oceans, including the Ports at the mouth of rivers in Africa, in contrast to wood and coal for steam engines, especially for gasification of suitable coal for gas engines and gasoline for explosion engines. This is also reflected in the price-performance ratio, expressed in Francs or Centimes per HP and operating hour:

... For the sake of clarity, I am summarizing the fuel costs for the PSe hour mentioned in my comments for the various types of engine covered: Steam engine with coal combustion. . approx. 60 ctms., Coal-fired gas machine. . approx. 40 ctms., Wood-fired steam engine. . approx. 15 ctms., Diesel engine with crude oil .. approx. 1 to 2 ctms….

In addition, there is a much greater range for diesel ships with the same weight of the fuel used:

... The diesel engine consumes only about 200g / PSe-st of these fuels, so that (!) The fuel price for this performance is less than 1 Pfg. The consumption of fuel in the diesel engine is so low that (!) The same machine output is achieved with the 15th part of the weight as when burning wood in steam engines; So if today's Congo steamship can travel 10 hours with 15 t of wood, a diesel ship with 15 t of fuel can travel 150 hours or 15 times as far ...

Finally, in the article he refers to the possible use of untreated vegetable oils in diesel engines, for example peanut or palm oil from local cultivation.

death

On September 29, 1913, Rudolf Diesel boarded the British ferry Dresden in Antwerp to cross over to Harwich and later in London at a meeting of Consolidated Diesel Manufacturing Ltd. to participate. He seemed to be in a good mood, but was not seen again after leaving the dining table that evening. His bed in the cabin was unused. On October 10th, the crew of the Dutch government pilot boat Coertsen saw the body of a man floating in the water in heavy seas. The body was badly decayed and was therefore not recovered.Instead, the sailors took some items from the clothes, such as a lozenge box, a wallet, a pocket knife and a glasses case, which belonged to his son Eugen Diesel on October 13th in Vlissingen as his father identified.

The exact circumstances of death could not be clarified. A suicide was discussed, but some circumstances on the ferry did not seem to correspond. The newspaper "L'Aéro" carried an article in 1934 about the death of the developer, in which it is reported that Diesel wrote a letter to his wife in Frankfurt on September 25, 1913 in Ghent , in which he expressed an oppressive feeling and a depressed mood speaks but gives no reasons for it. At the time, business in the English diesel company was very bad. Diesel was supposed to attend a meeting with the board of directors in London on October 1st and face criticism from some shareholders. That is why he was accompanied on his trip to London by Mr. Carels, director of “Diesel Belgium” in Ghent, and the engineer Luckmann.

The utopia of solidarism

Diesel also dealt with social issues. In 1903 he published a book called Solidarism: Natural Economic Redemption of Man . He outlined the idea of an economy based on solidarity, in which the workers organize the financing, production and distribution of goods themselves. Everyone should pay a small amount into a people's coffers. The money collected was to be used for guarantees and loans to joint operations of the treasury members.

The further development of the diesel engine

During the First World War , submarines were already equipped with marine diesel engines. The risk of fire and explosion was low compared to gasoline engines. In 1923 the first diesel truck was built. The first two series production cars with diesel engines, the Mercedes-Benz 260 D and the Hanomag Rekord , were presented at the International Automobile and Motorcycle Exhibition in Berlin in February 1936 .

During the Second World War , diesel engines proved to be superior to gasoline engines as a drive unit for tanks , as the range is greater and diesel fuel ignites more difficultly than petrol when fired at . The Soviet Union alone used diesel engines in the Red Army's main battle tanks from the start. After the Second World War, four-stroke diesel engines became widely used in tanks.

Today, diesel engines are also run on vegetable oil fuel ( e.g. rapeseed oil ) and biodiesel . Rudolf Diesel had already carried out promising tests with vegetable oils, and his diesel engine at the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris was powered by peanut oil. However, usable oils like peanut oil, like today's non-fossil fuels, were relatively expensive and therefore not economical.

See also the section The First Diesel Engine in the Diesel Engine article .

Honors

His bust is in the Hall of Fame in Munich. Many cities have a diesel road or alley. At the Technical University of Munich there is the "Rudolf Diesel Senior Fellowship" in the TUM Institute for Advanced Study for internationally outstanding guest scientists from industry. In 1957, the Rudolf Diesel Memorial Grove was laid out in the Wittelsbacher Park in Augsburg as the first Japanese rock garden in Germany. It is about 1,000 square meters and surrounded by hedges. The green area was designed with large boulders up to two meters high, which were transported to Augsburg by the Japanese river Inagawa. The grove was donated by Magokichi Yamaoka, then head of the Yanmar Diesel Works, which produced diesel engines in the Japanese cities of Amagasaki and Nagahama.

Named after him were u. a. on July 28, 1999 the asteroid (10093) Diesel , as well as the Nuremberg Rudolf Diesel Technical School founded in 1910 .

Keepsake through prizes

Diesel ring

The Association of Motor Journalists e. V. (VdM) has been awarding the golden diesel ring annually since 1955 to outstanding personalities who have made outstanding contributions to road safety .

Rudolf Diesel Medal

The German Institute for Invention (DIE) awards the Rudolf Diesel Medal every year .

Works

- Theory and construction of a rational heat engine to replace the steam engine and the combustion engines known today . Springer, Berlin 1893.

- Solidarism. Natural economic salvation for man. Author: "That I invented the diesel engine is all well and good, but my main achievement is that I solved the social question." R. Oldenbourg Verlag , Munich and Berlin 1903. Maro-Verlag, Augsburg 2007, ISBN 3-875124162 .

- Cooperative in-house production. How can organized consumption accelerate the transition to self-production? After a lecture given on the 1st ordinary day of the cooperative of the Central Association of German Consumer Associations on June 14, 1904 in Hamburg. Reinhardt-Verlag, Munich 1904, DNB 572860544 .

- The present status of the Diesel engine in Europe, and a few reminiscences of the pioneer work in America. Published by Busch-Sulzer Bros.-Diesel Engine Co. St. Louis, Missouri 1912, reference .

- The origin of the diesel engine. Springer, Berlin 1913. Facsimile with a technical and historical introduction and a portrait of Rudolf Diesel by Hans-Joachim Braun. Steiger, Moers 1984, ISBN 3-921564700 .

literature

- Eugen Diesel: Diesel. The person, the work, the fate . Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt, Hamburg 1937. Heyne, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-453-55109-5 .

- Eugen Diesel: inventor in the focus of the world, Rudolf Diesel and his engine . Reclam, Stuttgart 1937 ?, Stuttgarter Hausbücherei, Stuttgart around 1955.

- Eugen Diesel: Diesel, Rudolf Christian Karl. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 3, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1957, ISBN 3-428-00184-2 , pp. 660-662 ( digitized version ).

- Karl Ganser : Industrial culture in Augsburg. Pioneers and factory locks. context, Augsburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-939645-26-9 .

- Viktor Glass: Diesel . Novel. Rotbuch Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86789-030-4 .

- Horst Köhler: Rudolf Diesel. Inventor's life between triumph and tragedy . context, Augsburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-939645-57-3 .

- Rudolf Diesel - a contribution to the commemoration on the occasion of his 100th birthday . In: Motor Vehicle Technology 3/1958, pp. 84–89.

Numerous other works by Eugen Diesel in the Reclam publishing house and reprints.

Movies

- Diesel , a biographical film by Gerhard Lamprecht from 1942 , with Willy Birgel as Rudolf Diesel, tells Diesel's life from 1870 to 1898.

- Rudolf Diesel - The forgotten genius. Documentary film, Germany, 2000, 42:40 min., Script and direction: Birgit Eckelt, production: Bayerischer Rundfunk , summary by 3sat .

- The diesel puzzle. Documentary, docu-drama , Germany, Great Britain, France, 2010, 51:40 min. ( Arte ), 42 min. ( ZDF ) , script and director: Christian Heynen, production: Engstfeld Film, ZDF, arte, series: Terra X , First broadcast: August 21, 2010 on arte, February 16, 2011 on ZDF, table of contents with online video from ZDF.

- The Selandia and the death of Rudolf Diesel. Documentary, Denmark, 2012, 58 min., Book: Grant Eustace, director: Michael Schmidt-Olsen, production: Chroma Film, German first broadcast: October 26, 2013 on arte , synopsis by ARD .

- Rudolf Diesel and the Diesel Engine , Milestones in Science and Technology No. 95, 2006, 14:32 minutes

Web links

- Literature by and about Rudolf Diesel in the catalog of the German National Library

- List of Diesel's patents with the European Patent Office

- Mathias Bröckers : About the end of the oil age. Rudolf Diesel's visions. In: Telepolis , October 8, 2005

- About the biography: Timeline on rudolfdiesel.info

Digital copies of newspaper reports on the disappearance and death of R. Diesel in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in French:

- What is known about the disappearance of the engineer Rudolf Diesel In: Journal des débats politiques et littéraires , December 1, 1913, page 4

- The mysterious disappearance of the developer Diesel. In: Le Petit Parisien , October 3, 1913, page 2

- Ch. Reber: Diesel, was he murdered? In: L'Aéro , December 14, 1934 on page 6

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rudolf Diesel, 1858–1913 / biography . Dieter Wunderlich, Kelkheim. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ↑ Rudolf Diesel . wissen.de . Archived from the original on March 17, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ↑ (today the Holbein-Gymnasium Augsburg is located here )

- ↑ a b Rudolf Diesel . www.holbein-gymnasium.de. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ↑ Wolfgang A. Hermann, Martin Pabst, Margot Fuchs: Technical University of Munich: the history of a science company , Volume 1, Metropol, 2006, ISBN 978-3-938690-34-5 , 1023 pages, p. 99

- ↑ Patent DE67207 : Working method and design for internal combustion engines. Inventor: Rudolf Diesel.

- ↑ Andreas Knie: Diesel - career of a technology . Edition Sigma, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-89404-103-X

- ↑ Patent DE82168 : Internal combustion engine with variable duration of the fuel introduction taking place under changing overpressure. Inventor: Rudolf Diesel.

- ↑ Reprint Rudolf Diesel: Theory and construction of a rational heat engine to replace the steam engines and the combustion engines known today. Hardcover - 96 pages - VDI, Düsseldorf. (Reprint of the 1893 edition); ISBN 3-18-400723-5

- ↑ Johannes Bähr, Ralf banks, Thomas Fleming: The MAN. A German industrial history . CH Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-57762-8 , p. 207

- ↑ Rudolf Diesel: The Origin of the Diesel Engine. Springer, Berlin 1913. ISBN 978-3-642-64940-0 . P. 13

- ↑ Rudolf Diesel: The Origin of the Diesel Engine. Springer, Berlin 1913. ISBN 978-3-642-64940-0 . P. 22

- ↑ Rudolf Diesel: The Origin of the Diesel Engine. Springer, Berlin 1913. ISBN 978-3-642-64940-0 . P. 77

- ↑ corporate history Sulzer on sulzer.com see year 1898th

- ↑ Michaela März-Lehmann: The villa of the inventor Rudolf Diesel, published by the Archdiocese of Munich, 2011 (PDF)

- ↑ Rudolf Diesel, Die Motorschifffahrt in den Kolonien , published in Technik und Wirtschaft , self-published by the VDI on commission from Julius Springer, Berlin 1912, 5th year, pages 24 to 37

- ↑ Rudolf Diesel, Die Motorschiffahrt in den Kolonien , printed in Prometheus, Illustrierte Wochenschrift about advances in trade, industry and science No. 1159, Volume XXIII, pages 225 to 230, Berlin January 13, 1912, Verlag R. Mückenberger, available at [1] , accessed May 17, 2019

- ↑ Erwin Starke: How Rudolf Diesel died In: Der Tagesspiegel of September 22, 2013

- ↑ Roland Löwisch: The great riddle about the death of Rudolf Diesel. welt.de, September 29, 2013

- ↑ Volker Schmidt: How did Rudolf Diesel die? zeit.de, September 30, 2013

- ^ Rudolf Stumberger : The Utopia of Solidarism by Rudolf Diesel. In: ingenieur.de , August 12, 2011

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Diesel, Rudolf |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Diesel, Rudolf Christian Karl (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German engineer and the inventor of the diesel engine |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 18, 1858 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 29, 1913 |

| Place of death | English Channel |