Sibylle (prophetess)

A Sibylle ( ancient Greek σίβυλλα ), also incorrectly Sybille , is, according to the myth, a prophetess who, in contrast to other divinely inspired seers, originally prophesied the future without being asked. As with many other oracles, the prediction is mostly ambiguous, sometimes also in the form of a riddle .

Origin of the Sibyl

The archaic origins of the Sibyl are believed to be in the Orient. The roots of their worship are possibly to be sought in Asia Minor in the context of the mystery cults of an "earth mother" like Cybele . Through the encounter with forms of ancient oriental ecstatic prophecy , the understanding of the sibyl as a prophet , as a female counterpart or in contrast to the prophet developed over time . The original connection between the Sibyl and earth deities can often be seen in the place of residence assigned to her, on a boulder or crevice or in a rock cave, the Sibyl's Grotto .

Although it is conceivable that there is a historical personality behind the figure of the Sibyl, it is unclear whether such a historical (only) Sibyl ever existed. With the increasing popularity of the prophecies of the Sibyl in antiquity, several places claimed to be the true and original sanctuary ( Temenos ) of the Sibyl, especially Erythrai and Marpessus . There were also districts in numerous other places in which the Sibyl is said to have made her prophecies. Later literary traditions attempt to differentiate these different sibyls and to name them. With this, “Sibylle” became a more general term for female prophets of the hidden in antiquity. It is important for the understanding of a sibyl that she should utter her fortune telling - in contrast to the oracle - in ecstasy, in which one can also see a connection to the understanding of a Cassandra , also coming from Asia Minor .

There are two archaeologically documented Sibylle grottoes, although these are relatively recent as they date from Roman times. Today you can still visit a Sibylle Grotto in Cumae , near Naples. In the oracle site at Delphi in Greece there is a rock outside the temple and seat of the oracle, the “rock of the Sibyl”, possibly a sign of an archaic sanctuary and predecessor of the oracle.

The sibyls of antiquity

The Sibyl (s) of ancient Greece

In ancient Greece , prophecies by the Sibyls were probably initially unknown. This is how Homer describes oracles and seers, but no sibyl is mentioned. Other authors also use it before the 5th century BC. Chr. Not to be found. A first verifiable written description of a Sibyl is then handed down in the fragment (Fr. 92) of a text by Heraclitus of Ephesus . In works by Plato , Aristophanes and Euripides , Sibylle n is spoken in the plural. The authors assume that the readers of their works or the audience of their plays were generally familiar with the nature of the Sibyls. This can be seen as evidence of the spread of this form of divination in ancient Greece and its colonies, at least from this time onwards, even if some authors of the time viewed the Sibyls more critically than z. B. the oracle of Pythia in Delphi . The acceptance and popularity of the (various) sibyls can be found in the Hellenic- speaking area well into the 4th century AD.Collections of their mostly cryptic words are disseminated - often in secret - by the followers of this form of divination and interpreted in the sense of the time .

The Sibylline Books of Rome

The original Roman religion contained elements of the Etruscan religion . In general, the culture of the Etruscans had developed parallel to that of Greece. Their religion used the liver inspection (Haruspician) and the interpretation of the flight of birds ( auspices ) to interpret the future. Intensive contacts in the Mediterranean area also had an effect on them through Greek traditions.

In this context, the official cult of the Sibylline Books developed in Rome as a further form of interpretation. However, these books must not be equated with the other Sibylline divinations of ancient Greece, which were still widespread in the Hellenic-speaking area. The books of Rome were a collection of traditional proverbs in Greek hexameters , administered in the temple by men entrusted with the supervision. Thus, these books are not assigned to a sanctuary of the Sibyl and none of these seers was to be honored if the books were consulted on behalf of the Senate in times of crisis. Only a few original verses from the Sibylline books have survived in the Book of Miracles of Phlegon von Tralles (2nd century); the books themselves burned in 405.

However, a sibyl named by name plays a role in the myths of Rome, for it is the Cumaean sibyl who serves Aeneas as a guide in the underworld after his landing in Italy; It is also she who predicts the great future of the city for him, so Virgil in the Aeneid . It can therefore be assumed that at least in Virgil's time the figure of one or more sibyls could also play a role in the understanding of Roman citizens (and not only in colonies with a Hellenic or oriental influence). It should be noted that 204 BC The cult of the Roman goddess Magna Mater was introduced in Rome. This “Great Mother” corresponded to the goddess Cybele , who came from Phrygia in Asia Minor and whose symbol, a black stone, was brought to Rome at that time.

The Sibyls at the end of the Roman Empire

The early Christian Sibyl

In the understanding of religion of the Roman Empire, especially in provinces with predominantly Hellenic culture or Oriental influence, was the Sibyl (or the Sibyls) as a medium of deity many familiar concept. Therefore, early Christianity had to or could deal with its importance for the “ Gentile Christians ”, to whom the prophecy of the Old Testament was alien. Some church fathers such as Augustine analyze the search for “God's words” in the Sibyl, which enabled the Sibyl to find its way into the written tradition of Christianity . As a result of this development, some parts of the Sibylline texts that were written in the Hellenic environment remained in circulation, primarily in the Alexandrian and then the Byzantine regions; however, the texts were reshaped in a Christian way and connected with prophetic ideas. From this the concept of the Sibyls of the Middle Ages developed , in which the Sibyls, like the prophets , were regarded as heralds of the bringing of salvation and whose texts could be found in the monastery libraries of the time. The Oracula Sibyllina emerged from these texts , whereby the original and the adaptation of the Sibylline prophecies can no longer be separated without further investigation.

The Jewish Sibyl

About Jews who were familiar with Greek culture had already started in 140 BC. The Greek-written text spreads about a Chaldean-Jewish sibyl named Sabba or Sambethe , who was identified with a Babylonian or Egyptian prophetess. These texts used a medium familiar to the Greeks to popularize the concept of the messianic expectation of salvation outside the Jewish communities and to explain this belief. For the most part, these are fragments of these texts that were edited in the Oracula Sibyllina .

The ten sibyls of Varro

Varro , a 1st century BC Roman historian Chr., Distinguished in one of his books ten sibyls, each provided with a geographical epithet according to their alleged place of origin , e.g. B. Sibylla Persica , Sibylla Libica etc. Varro's book is not preserved in the original text, but the church father Lactantius , the tutor of Crispus , the son of Emperor Constantine , lists them in his book of divine instructions according to Varro. This listing of the Sibyls thus becomes a central source for a further understanding of the number and meaning of the Sibyls in subsequent literature and art. The ten sibyls named by Varro are:

- Persian Sibyl

- Libyan Sibyl

- Sibyl of Delphi

- Cimmerian Sibyl

- Sibyl of Erythrai

- Sami Sibyl

- Sibyl of Cumae

- Hellespontic Sibyl

- Phrygian Sibyl

- Tiburtine Sibyl

The Sibyls of the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages , texts with Sibylline oracles were distributed among scholars . These should contain apocalyptic prophecies of various sibyls. Popular figure who also was from Augustine called Erythraean Sibyl (through their words from the "day of judgment" in Latin , this Irae ). Next came legends to Christian visions of the Sibyl of Tibur or other Sibyls whose pictorial representations of Gothic churches and later input into healing mirror and popular world chronicles such. B. the Schedelsche Weltchronik of 1493, maintained the popularity of the Sibyls for a long time.

In the late Middle Ages , two more sibyls are sometimes added to the ten sibyls named by Lactantius, in order to bring their number into line with that of the so-called twelve minor prophets of the Old Testament. These are the Sibylla Agrippina and the European Sibyl .

Sibyl representations in art

Sibyl representations in the Renaissance and the Italian early modern period

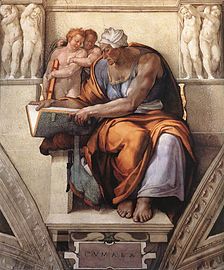

- The Sibyls of Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel

Probably the best-known representation of the Sibyls can be found in the ceiling frescoes of the Sistine Chapel painted by Michelangelo from 1512. In addition to seven prophets, five Sibyls are also shown. Similar representations were common in the Italian Renaissance; B. from:

- Raphael the fresco of the Sibyls in the church of Santa Maria della Pace in Rome or from

- Pinturicchio the alternating depiction of sibyls and prophets in the Appartamenti Borgia of the Vatican .

In Italy sibyl representations were more widespread in the 16th century. B. in the Oratorio del Gonfalone.

Sibyl representations in the Moldavian monasteries

A sibyl as a motif can also be found in depictions of the “family tree of Jesus” on the outside walls of the church of the Sucevița monastery and other Romanian Orthodox churches from the late 16th century. These are to be seen in connection with the Byzantine tradition of the Sibylle interpretation.

Sibyls in the art of the Middle Ages

The topic is not new, however, but can already be found in numerous representations of the Gothic in Italy, France, the Netherlands / Belgium, as well as in Germany and Austria, among others in the following places:

- Orvieto : In the “Family Tree of Jesus” in the facade of the cathedral you can find a sibyl next to the prophets, created by Lorenzo Maitani (1255–1330).

- Ghent : In the two middle lunettes on the weekday side of the Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck from 1432, two sibyls are depicted, next to them two prophets .

- Bruges : In the so-called Bladelin Altar , created by Rogier van der Weyden between 1445 and 1448, there is a representation of the vision of the Tiburtine Sibyl.

- Gurk : The Sibyl of Tibur can be found on the Lent cloth of Gurk Cathedral from 1458.

- Goslar : In the so-called tribute hall in the town hall of Goslar, the complete Sibyl cycle is depicted on mural paintings together with imperial figures. The work was carried out by an unknown artist around 1520, the master of the Goslar Sibyls

- Ulm : At the three seat and in the choir stalls of the Ulm Minster , by Jörg Syrlin the Elder. Ä. and Michel Erhart, created between 1468 and 1474, a total of ten named Sibyls are represented in an ensemble with ancient scholars and in the overall program of (holy) men and women of the Old and New Testaments.

- Cologne : The master of glorification Mariae depicted Emperor Augustus and the Sibyl of Tibur in a picture around 1470.

- Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges : In the cathedral of the town in the south of France you can find representations of 13 named Sibyls from 1535 in the choir stalls on wooden panels.

Some Gothic sibyl depictions can also be found in Spain (e.g. in Zamora ) and Portugal.

Sibyl representations in the Baroque

- Admont Abbey Library : In the library hall, the sculptor Josef Stammel (1695–1765) created eight smaller, gilded busts of Sibyls, which stand among a large number of busts of ancient scholars

- Schönbrunn Palace : Among the sculptures around Schönbrunn Palace is the Sibylle von Cumae in the ranks of other (mythical) figures, created in the period from 1773 to 1780 under the direction of Johann Christian Wilhelm Beyer .

See also

literature

- Jürgen Beyer: Article Sibyllen ; in: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Concise dictionary for historical and comparative narrative research , Vol. 12; Berlin, New York: de Gruyter, 2007; Col. 625-630

- Rolf Götz: The Sibylle von der Teck. The legend and its roots in the sibyl myth ; Series of publications by the Kirchheim unter Teck City Archives, 25; Kirchheim unter Teck 1999

- Emily Gowers: Virgil's sibyl and the 'many mouths' cliché (Aen. 6.625-7) ; in: The Classical Quarterly 55 (2005), pp. 170-182

- Werner Grebe (Ed.): Sibyllen Prophecy. Facsimile edition of the Volksbuch around 1525 with an introduction, translation and notes ; Old Cologne folk books around 1500, 6; Cologne 1989

- Christian Jostmann: Sibilla Erithea Babilonica. Papacy and prophecy in the 13th century ; MGH Writings, 54; Hanover 2006 ( PDF )

- Marie Luise Kaschnitz : Greek Myths. Insel, Frankfurt a. M. & Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-458-17071-5 , pp. 13-20 (poetic retelling of the myth)

- Alfons Kurfess , Jörg-Dieter Gauger (Ed.): Sibylline prophecies. Greek-German ; Tusculum Collection; Düsseldorf, Zurich: Artemis and Winkler, 1998; ISBN 3-7608-1701-7 .

- Ernst Sackur: Sibylline texts and research. Pseudomethodius, Adso and the Tiburtine Sibyl . Hall 1898

- Wolfger Stumpfe: Sibyl representation in Italy in the early modern period. About the identity and meaning of a pagan-Christian figure ; Diss. University of Trier 2005. There also current bibliography (pp. 189–204) and directory “important [r] sibyl representations in Italy of the 15th – 17th centuries. Century ”(pp. 186–188).

- Wilhelm Vöge: Jörg Syrlin the Elder and his sculptures , Volume 2: Circle of material and design ; Berlin: German Association for Art History, 1950.

Web links

- Tiburtinische Sibylle Latin text after the edition by Sackur (1898)

- Dr. JH Friedlieb: The Sibylline Prophecies, completely collected German text (1852)

Remarks

- ↑ So z. BHW Parke: Sibyls and Sibylline Prophecy in Classical Antiquity ; Routledge, 1992; ISBN 0-415-07638-2 .

- ↑ See e.g. B. Baedeker Travel Guide Greece , 2008

- ↑ a b cf. z. B. Roland Baumgarten: Holy Word and Holy Scripture among the Greeks: Hieroi Logoi and related phenomena (= ScriptOralia. Series A, Classical Studies Series; Vol. 26). Narr, Tübingen 1998. ISBN 3-8233-5420-5 . At the same time dissertation at the University of Freiburg (Breisgau), 1994.

- ↑ See article Sibyllen , in: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon Volume 18, Leipzig 1909, p. 419.

- ^ Des Lucius Caelius Firmianus Lactantius writings . Translated from Latin by Aloys Hartl. Library of the Church Fathers, 1st row, Volume 36. Munich 1919. Chapter 5.

- ↑ Article Sibylle ; in: Peter W. Hartmann: The large art dictionary ; [Sersheim]: Hartmann, 1997; ISBN 3-9500612-0-7

- ↑ See e.g. B. Vatican Radio: The Appartamenti Borgia

- ↑ Wolfger Stumpfe: Sibyl representation in Italy in the early modern period. About the identity and meaning of a pagan-Christian figure ; Diss. University of Trier 2005.

- ↑ Cf. on this Wilhelm Vöge: Jörg Syrlin the Elder and his Bildwerke , Volume 2: Stoffkreis und Gestaltung ; Berlin: German Association for Art History, 1950.

- ^ Jürgen Wiener: Lorenzo Maitani and the cathedral of Orvieto ; Studies in international architecture and art history, 68; Petersberg: Imhof, 2008; ISBN 978-3-86568-256-7 .

- ↑ Otto Rainer: Fastentuch. Gurk Cathedral ; Gurk: Domkustodie, 2005 2 ; ISBN 3-901557-01-6 ; P. 15 f.

- ^ Franz Härle: The choir stalls in Ulm Minster ; Langenau: Vaas, 1994; ISBN 3-88360-115-2 .

- ↑ Thomas Blisniewski : Emperor Augustus and the Sibyl of Tibur. A picture of the Master of Glorification Mariae in the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum - Fondation Corboud . In: Kölner Museums-Bulletin 3/2005, pp. 13–26.

- ↑ T. Nagel: Museums in Cologne: picture of the 51st week - December 22nd to 28th, 2008 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ).

- ↑ Le Rosslyn français? Les Carnets Secrets 9 (2007)

- ↑ Franz Krahberger: Admontisches universe - A baroque multimedia research ; Electronic Journal, after 1994