Ortisei-and-Levin

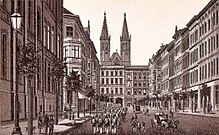

The St. Ulrich and Levin Church , or Ulrichskirche for short , was the second oldest parish church after St. Johannis and a landmark in Magdeburg . After suffering damage in the Second World War , the ruins were blown up in 1956, despite the fact that they could be rebuilt.

location

The Ulrichskirche, as it was also called, was located on Alten Ulrichstraße , which was renamed Ulrichplatz in 1998 . Their foundations are under a flower bed on the northern edge of the green area. The north facade of the church ended roughly with the footpath of Ernst-Reuter-Allee, the choir (east facade) stood opposite today's bronze model and the restaurant "Alex". Nowadays the west and south facades are defined by lawns. The large fountain is located well south of the old original location of the church.

history

It is believed that the Ulrichskirche was built in the first third of the 11th century. A Ortisei community was first mentioned in writing in Magdeburg as early as 1022. The foundation of the church is often associated with the construction of the Geros city wall between 1012 and 1023 . Bishop Ulrich von Augsburg is accepted as the namesake. It is unclear whether the church initially existed as a branch church. The first building was probably a simple wooden or half-timbered church. The foundations and tower floors are likely to have been made of stone. It is conceivable that there was previously a small chapel dedicated to St. Ulrich. The provost of Magdeburg Cathedral had the right of patronage and was therefore able to appoint the clergy of the Ulrichskirche to their office.

In a city fire in 1188, the Ulrichskirche also burned down. After the reconstruction, the church was also dedicated to Saint Levin , who was mainly venerated in Flanders . Flemish merchants immigrated to the Magdeburg region. The first written mention of the double name dates from 1464; it is believed that the dedication was made much earlier, possibly towards the end of the 12th century. The first written mention of the Ulrichspfarrei comes from the year 1197, that of the Ulrichskirchhof as Olriken kerkove from 1330, whereby it is assumed that the cemetery existed much earlier and was probably located north of the church and was then extended to the east and south.

Wealthy merchants had a great influence in the parish of Ulrichskirche, after initially farmers had dominated due to the location on the western edge of the city. The rebuilt church was probably built on the foundations of the previous building as a single-nave hall church with two stone towers. It is assumed that the lower three tower floors, which existed until 1956, went back to this construction phase.

In 1349 the patronage was transferred to the provost of the monastery of Our Dear Women . The church was thus under the order of the Premonstratensians . Already by one of Pope Boniface IX. issued certificate of May 8, 1401, the patronage right was transferred to the cathedral chapter. In 1461, the monastery of Our Dear Women regained control, whereby the cathedral chapter tried several times to assert claims.

In 1425, the city of Magdeburg set up a grain store in a building at the back of the Sankt Ulrich parish due to an increase in grain prices, from which grain was sold to the residents.

In the side aisles of the church there were various side altars that went back to private foundations. The copy book of the church from 1542 showed ten such side altars. They were consecrated to Saints Martin, Barbara, Petrus, Andreas, Levin, Anna, Katharina, Johannis Evangelista, the three wise men and the eleven thousand virgins. The reredos by Johannis Evangelista is still preserved today and is in the Wallonerkirche . The last foundation of such an altar before the Reformation is recorded for the year 1464. The Hönbode brothers donated the Sankt-Annen-Altar at that time. It was customary that in connection with the foundation, care was also given to the individual position of a clergyman. These so-called altarists or vicars took care of the pastoral care of the respective altar. In the 15th century, in addition to the actual pastor at the Ulrichskirche, ten altarists and two more clergymen were active.

The church played a special role during the Reformation . In September 1524 Nikolaus von Amsdorf , a close confidante of Martin Luther , became a preacher to Sankt Ulrich and at the same time superintendent of Magdeburg. From here Amsdorf drove the Reformation in Magdeburg. After the occupation of Wittenberg by imperial Catholic troops in 1547, many scholars from the University of Wittenberg fled to Magdeburg. In the rectory of Sankt Ulrichs they wrote hundreds of pamphlets against the emperor and for Protestantism. This is where the nickname Our Lord's Chancellery, which is often used for the city, comes from . Pastors at this time were Matthias Flacius and Johann Wigand .

Also Nicolaus Gallus and Matthew Judex worked here. Flacius and Wigand are said to have negotiated with the besiegers Moritz of Saxony during the siege of the city in 1550/51 and to have a share in the favorable outcome of the dispute for Magdeburg.

After the end of the siege, Flacius and Wiegand initiated the Magdeburg Centuries in the Ulrichskirche , a detailed work on church history that is still widely recognized today .

Since 1567 Georg Rollenhagen belonged to the Ulrichsgemeinde. The writer and rector of the old town high school was buried under the towers of the church in 1609. In 1607 the congregation set up another cemetery in front of Ulrichstor, especially for poor members of the congregation. Reinhard Bake , who later became known as a theologian and cathedral preacher , was employed as a deacon in the Ulrichskirche in 1610 . Christian Gilbert de Spaignart , who achieved reputation as a German economist, was pastor at the Ulrichskirche from 1620.

When Magdeburg was destroyed in the Thirty Years War , the Ulrichskirche was also damaged. The reconstruction took place from 1648 to 1656. In 1655 the composer Malachias Siebenhaar became the second preacher at the church. Balthasar Kindermann was the first preacher in the Ulrichskirche from 1672.

The Wredekapelle was built on the south side of the church from a foundation made by the businessman Matthias Wrede , who died in 1678 . In 1699 an organ was installed in the Ulrichskirche by the well-known organ builder Arp Schnitger . In 1713 the sculptor Severin Gottlieb Ziegenbalg was buried here. In 1742 Otto Nathanael Nicolai became a deacon at the Ulrichskirche. August Mühling became organist at the Ulrichskirche in 1823 until he took over the position of organist at Magdeburg Cathedral in 1843.

On June 9, 1861, a fire broke out as a result of a lightning strike . The roof, the two towers and part of the vault near the towers were destroyed or badly damaged. The interior of the church was hardly damaged, so that a service could take place again on July 14, 1861 . The final reconstruction, especially the towers, dragged on until 1866. The two towers were redesigned in a neo-Gothic style. A roof turret on the nave was not renewed.

On November 6, 1928, Günther Dehn , at the invitation of Oskar Zuckschwerdt , who has been pastor at the Ulrichskirche since the end of 1922 , gave a momentous lecture on “Church and Reconciliation” in the parish hall of the Ulrichskirche. Although he affirmed the right to a war of defense and rejected conscientious objection , he questioned, among other things, the erection of war memorials in churches. Dehn's statements were taken to mean that he took the view that soldiers were murderers. This caused great public outrage.

The church gained importance during the time of the National Socialist tyranny . Zuckschwerdt joined the Confessing Church and the Pastors' Emergency League . Zuckschwerdt became known nationwide because he baptized the Jew Albert Hirschland on March 17, 1935 . Hirschland was arrested on April 20, 1935 on charges of racial disgrace . The anti-Semitic magazine Der Stürmer attacked Zuckschwerdt massively. In 1937, Zuckschwerdt was charged with abuse of the pulpit and with a violation of the Collection Act . After several months of pre- trial detention , the proceedings against him were discontinued in 1938. Zuckschwerdt became provost of the Magdeburg district in 1946 .

During the air raid on Magdeburg on January 16, 1945 , the characteristic twin towers and the west facade were completely preserved. The roof and vault of the three-aisled nave collapsed, only the outer walls and the Gothic pillars remained.

On April 20, 1950, it was decided to unite the previously independent old town parishes of Sankt Ulrich and Levin, Sankt Katharinen, Sankt Jakobi, Sankt Petri and Heiliggeist to form the old town congregation, since according to the church constitution every congregation had to have a preaching site, but many of the congregations had to do so the war damage had no buildings intact. The state government of Saxony-Anhalt confirmed this decision on October 1, 1950, with which the association came into force. This decision aroused concerns within the church, especially among the provost, as it was feared that it would have negative effects on the existence of the non-parish church buildings. In fact, the Luther Church , which was partially destroyed in 1944, was demolished in 1951. The burned out German Reformed Church was demolished in 1955.

During the reconstruction of the city of the GDR , which in the sense of the ideology of socialism under Mayor Philipp Daub deliberately broke with the previous urban design, the Ulrichskirche was seen as a disruptive element and was blown up on April 5, 1956, although the cost and effort of the demolition was a reconstruction would have been the same. The area that has become free was greened. Magdeburg thus lost a building that had significantly shaped the cityscape and city history. In 1959 two secularized churches were demolished and three other churches blown up: Sankt Jakobi (burned out, towers and enclosing walls largely intact), Martinskirche and Heilig-Geist-Kirche (Sankt Spiritus: rebuilt from 1948 to 1950, was used). On October 20, 1960, the French Reformed Church (burnt out in 1945) was blown up and in 1964 the nave of Sankt Katharinen . Their towers were dismantled with a pickaxe.

After German reunification, the area to the east was rebuilt. The building erected there was named "Ulrichshaus" in memory of the former church. The area on which the church stood was named "Ulrichplatz" in 1998.

- Ruin and demolition of the Ulrichskirche in 1956

Planned reconstruction

On the private side there are efforts to initiate a reconstruction of the church. On October 31, 2007, around 60 founding members of the Sankt-Johannis-Kirche founded the board of trustees for the reconstruction of the Ulrichskirche . The board of trustees has set itself the goal of collecting donations and aimed to reopen the Ulrichskirche on October 31, 2017, the 500th anniversary of Luther's posting of the theses, as a “documentation center of Protestantism”. The initiative has many prominent supporters, especially from politics, and raised the public's awareness of the topic through a number of high-profile campaigns. The number of members of the Board of Trustees rose to over 300.

The Lord Mayor of Magdeburg, Lutz Trümper , applied to the city council to initiate a referendum to rebuild the Ulrichskirche. The mayor declared in April 2010: "In my opinion, this is an important community matter that justifies a referendum." However, this motion failed to achieve the necessary two-thirds majority. In contrast, the Magdeburg city council announced on June 24, 2010 that it would support the project and keep the property free until 2017 for the reconstruction of the Ulrichskirche.

As a result, a citizens' initiative collected more than 13,000 signatures in order to force a referendum on this issue, mostly with the motivation to prevent reconstruction in this way. As a result, the city council decided on January 27, 2011 to carry out the referendum parallel to the state elections in Saxony-Anhalt 2011 on March 20, 2011. The turnout was 56.3 percent; 76% of voters voted against the reconstruction.

Todays situation

Various parts of the Ulrichskirche were moved to other locations. A sandstone retable from the side altar of the Evangelist Johannes from the 14th century has been preserved and is located in the Magdeburg Wallonerkirche . The epitaph of the merchant Hogenbogen from 1452, Ludwig Aleman from 1543 and the cartouche tombstone of the timber merchant Konrad Schlueter from 1735 are also placed there. In the choir of this church there is also the figure of an angel playing the harp, which was part of the organ front of the Ulrichskirche. The epitaph of the child Thomas Alemann , who died in 1575, was attached to the Sankt-Johannis-Kirche . Another epitaph, that of Emeramus Scheiring , who died in 1547 , is housed in the cloister of Magdeburg Cathedral. The tower clock from 1880 was expanded on April 3, 1956 and has since been in the Sankt-Ambrosius-Kirche in Magdeburg- Sudenburg . After a necessary restoration, the movement has been in the Magdeburg Wallonerkirche since mid-2013. The clockwork has been exhibited in the millennium tower of Magdeburg's Elbauenpark since June 22, 2016 .

Parts of the stones of the blown up church were used to build the Magdeburg Zoo. After such structures were demolished, stones from the church, including column parts, capitals and sandstone surrounds, were recovered and kept. It is also assumed that the foundation walls and the lower church are still in place.

literature

- Helene Penner: The Magdeburg Parish Churches in the Middle Ages (Phil. Diss. University of Halle 1919), printed in: Saxony and Anhalt - Yearbook of the Historical Commission for Saxony-Anhalt , 2017, Volume 29, pp. 19-104, here pp. 36– 40.

- Hans-Joachim Krenzke: Churches and monasteries in Magdeburg , 2000.

- Tobias Köppe: The Magdeburg Ulrichskirche - history. Present. Future. , Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-86568-677-0 .

- Magdeburger Volksstimme of January 28, 2011: Council follows the will of the people: The citizens now vote on the church .

Web links

- Reconstruction initiative, pictures of the church building

- Citizens' initiative "Dare democracy - ask citizens!"

- 3D model of the Ulrichskirche in today's city

Individual evidence

- ↑ Tobias Köppe, Die Magdeburg Ulrichskirche , Michael Imhof Verlag Petersberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-86568-677-0 , p. 12.

- ↑ a b Tobias Köppe, Die Magdeburg Ulrichskirche , Michael Imhof Verlag Petersberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-86568-677-0 , p. 21.

- ↑ Tobias Köppe, Die Magdeburg Ulrichskirche , Michael Imhof Verlag Petersberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-86568-677-0 , p. 24.

- ↑ Tobias Köppe, Die Magdeburg Ulrichskirche , Michael Imhof Verlag Petersberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-86568-677-0 , p. 29.

- ↑ a b www.kirchensprengung.de

- ↑ ulrichskirche.de ; Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ↑ idea, April 8, 2010 and press release from the city of Magdeburg, see also the weblog “Magdeburg can do more” ( memento of the original from October 16, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ See article Ulrichskirche in Magdeburg. In: Bauwelt 8.2011.

- ^ Results of the referendum .

- ^ Rainer Schweingel: The clock will strike in the future in the millennium tower. Retrieved July 25, 2018 .

Coordinates: 52 ° 7 '50.6 " N , 11 ° 38' 3.1" E