St. Gallen embroidery

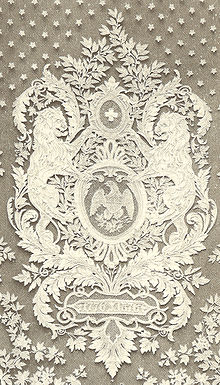

As St. Gallen embroidery refers to embroidery -products from the city and region of St. Gallen . This region was once one of the world's most important and largest manufacturing and exporting areas of embroidery products. Around 1910 embroidery production was the largest export branch of the Swiss economy with 18 percent and over 50 percent of world production came from St. Gallen. With the beginning of the First World War , the demand for the luxury item fell sharply. As a result, a large number of employees became unemployed, which led to the region's biggest economic crisis. Today the embroidery industry has recovered to some extent, but has never returned to its former size. Nevertheless, St. Gallen lace is still a popular raw material for expensive Parisian haute couture creations .

history

Beginnings

Initial figures suggest that the St. Gallen embroidery industry already had up to 100,000 employees at the end of the 18th century, long before the invention of the hand embroidery machine . This number is probably a bit exaggerated, but it is an indication of the importance of embroidery in Eastern Switzerland . The increase in importance of embroidery went hand in hand with the decline of the canvas industry , especially in the city of St. Gallen itself. The canvas industry was permanently weakened by the cotton industry introduced by Peter Bion and by foreign competition. Those who could no longer make a living in the cotton industry turned to embroidery. At the latest during the continental blockade around 1810, the cotton industry also fell behind. The general society of the English cotton spinning mill in St. Gallen , which was founded in 1801 as the first stock company in Switzerland , had to close again in 1817 due to a lack of money.

First embroidery machines

The great boom of the embroidery industry began in 1828 with the invention of the hand embroidery machine by Josua Heilmann von Mulhouse. Just one year later, Franz Mange (1776–1846) acquired two such machines from Heilmann on the condition that he was not allowed to sell any further machines to Switzerland or its immediate vicinity without Manges's consent. However, Mange allowed the machine workshop and iron foundry , which Michael Less had recently opened in St. Georgen, to manufacture such machines. He himself had worked on improving the design and had already exported several machines abroad, albeit without any lasting success for the industry there, especially since the machines were not yet fully developed and therefore not suitable for the market. In 1839 Mange's business was passed on to his son-in-law Bartholome Rittmeyer (1786–1848), and shortly afterwards to his son Franz Rittmeyer (1819–1892). Together with his mechanic and thanks to the support of Anton Saurer , he managed to improve the machines to such an extent that the quality of the machine-produced embroidery almost matched that of hand embroidery. The improved hand embroidery machines were produced in series from 1852, including in the machine workshop and iron foundry . Over 1500 pieces had been produced by 1875.

These machines from that time had the disadvantage that they could only be used to produce ribbon-like embroidery. The simultaneous invention of the sewing machine offered a remedy here, however, since smaller embroideries could now also be sewn onto cloths on a large scale. A Hamburg merchant called this new method Hamburghs to deceive the competition about the origin of the item.

Rittmeyer had to relocate and expand its factories several times, as the existing capacities could no longer meet the constantly increasing demand. In the embroidery factory in Bruggen, which was completed in 1856 (later relocated to the Sittertal ), 120 machines were at work at times.

Rapid ascent

The meteoric rise of St. Gallen embroidery can only be explained as a happy coincidence of economic, political and technical circumstances in the second half of the 19th century. In the political environment, these were the end of the American Civil War and the incipient free trade policy , in the economic environment - among other things - the fashion of the second Rococo , which was very popular at the French court, and in the technical environment, the further development of machines.

In the years after 1860, the demand for embroidery products increased so much that embroidery shot up like mushrooms. Many farmers, craftsmen and former weavers had an embroidery machine installed in their home for a down payment. So embroidery soon became largely home work , as an important additional income for farmers and craftsmen. This is mainly done in winter, as was sometimes the case in the canvas and spinning mills. The home work model offered certain advantages both for the home work stickers themselves and for the entrepreneurs. For the former it was especially the bad reputation of the " factory " and the dependence on a single employer that moved them to this form of business; for the latter, the possibility of being able to use capacities at very short notice and to let the whole risk rest on the stickers in the event of a decline in orders. The stickers also appreciated the freedom to organize their working hours and the unrestricted use of child labor , especially since the introduction of the Federal Factory Labor Act of 1877, which banned young people under the age of 14 from working in factories.

The merchants , who imported the raw materials, distributed them to the embroiderers and sold the finished products all over the world, particularly benefited from the rapid development of home embroidery . In the period from 1872 to 1890, the number of embroidery machines installed in the cantons of St. Gallen , Appenzell Ausserrhoden and Thurgau increased from 6,384 to 19,389, but at the same time the proportion of machines installed in factories rose from 93% to 53% from. The value of goods exported to North America increased from CHF 3.1 to over CHF 21 million between 1867 and 1880 .

Representatives of trading houses from overseas regularly visited St. Gallen to select the embroidery samples and place new orders. Trading houses were also set up in St. Gallen, sending embroidery design designers to the most important markets and selling the goods produced all over the world. The freight forwarding company Danzas, for example, advertised itself extensively in newspapers and praised itself as a “special agency for embroidery and finishing traffic in St. Gallen” with post and express steamers to North America, East India , China , Japan , Australia and various other places. The commercial corporation made major efforts to improve the framework conditions for export trade. She built a bonded warehouse in St. Gallen, opened a school for pattern designers and what is now the textile museum . She was also involved in the so-called embroidery exchange , a kind of market for manufacturers , merchants, ferggers (intermediaries), embroiderers and finishers .

Further developments

The embroidery industry received a further boost after the invention of the ship embroidery machine by Isaak Gröbli from Oberuzwil in 1863. A test ship embroidery machine was first built in the Benninger company in Uzwil , then further development and series production took place at Rieter in Winterthur. In 1879 the Iklé brothers put the first ship embroidery machines into operation in St Gallen.

First crisis

St. Gallen embroidery suffered a temporary severe setback around 1885 as a result of overproduction in a time of economic crisis . Orders suddenly plummeted, with wages falling sharply. It was not until 1898 that embroidery recovered through various internal reforms (restrictions on maximum working hours, introduction of minimum wages) and the upturn in the world economy.

The manufacturers essentially pursued two different interests: Those who concentrated on exporting to the United States preferred to have goods manufactured in bulk. However, the long-established export houses preferred creations that were as complex and expensive as possible that were geared towards the needs of Parisian haute couture .

New technical development

The last decisive step in the technical development of embroidery was made in 1898 with the invention of the Schiffli machine by Arnold Gröbli, a son of Isaak Gröbli . With this device , the pattern is no longer specified via the pantograph , but rather via punch cards . The first machines were imported from the Vogtland machine factory in the Saxon city of Plauen until Saurer in Arbon found the technical connection with his machine construction after 1912 and was thus able to supply the Swiss and Vorarlberg markets. The Schiffli and hand embroidery machines did not die out completely, despite the significantly increased production of the machines, since the preparation of the punched cards with the patterns for small series was often not worthwhile. Since the various embroidery products sometimes had to meet completely different requirements, hand embroidery machines were still used for some orders in 1945, or the order was embroidered entirely by hand.

St. Gallen embroidery experienced its greatest boom in the period before the First World War , around 1894. Embroidery exports - around 95% of all embroidery produced were exported - reached their peak in terms of both quantity and value. If one compares the value of the exported embroidery (1912: CHF 219 million) with that of other export goods such as watches (1911: 187 million) and silk (1911: 155 million), the importance of this product for the whole of Switzerland becomes apparent Economy . This market made St. Gallen one of the richest cities in Switzerland and accordingly magnificent was built during this time. This can still be seen today on the bay windows of the old town and on the representative buildings of the former embroidery trading houses, which mainly date from this period.

The great crisis and the resurgence

| year | Quantity (tons) | Value (in CHF 1000) |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 8917.1 | 204,064 |

| 1911 | 9259.3 | 215,390 |

| 1912 | 8940.7 | 218,889 |

| 1913 | 8918.2 | 209,743 |

| 1914 | 6719.5 | 157,600 |

| 1915 | 7224.3 | 181,664 |

| 1916 | 7371.3 | 230,205 |

| 1917 | 5427.4 | 227,270 |

| 1918 | 4352.0 | 276,098 |

| 1919 | 5694.7 | 410,036 |

| 1920 | 5335.7 | 391,858 |

| 1921 | 2574.1 | 126,094 |

| 1922 | 3494.3 | 143'200 |

| 1923 | 3861.2 | 153,011 |

| 1924 | 3587.7 | 156,608 |

| 1925 | 3088.2 | 129,130 |

| 1926 | 3232.1 | 119,288 |

| 1927 | 3279.8 | 116,283 |

| 1928 | 3173.4 | 109,733 |

| 1929 | 2444.3 | 88'234 |

| 1930 | 1735.0 | 65'111 |

| 1931 | 1372.1 | 49,173 |

| 1932 | 835.8 | 22,633 |

| 1933 | 944.2 | 21,120 |

| 1934 | 716.7 | 14,851 |

| 1935 | 630.8 | 12'252 |

| 1936 | 1020.6 | 15,848 |

| 1937 | 1255.2 | 26,882 |

| 1938 | 1178.6 | 25,480 |

| 1939 | 1396.6 | 28,372 |

| 1940 | 686.6 | 17,138 |

Second crisis

The decline of the embroidery industry began in 1914 with the outbreak of the First World War. The demand for luxury products - embroidery has always been one of them - collapsed suddenly, and the free trade zones virtually no longer existed. In some cases, neutral states increasingly appeared as buyers; however, this could only compensate for the sales problems for a short time. In addition to the difficult export, there were also significant price increases for the yarn to be imported. In order to keep wages from free fall to some extent, maximum working hours and minimum wages have now been set. In fact, these measures were rather counterproductive - only those who were willing to work for less than the minimum wage were hired.

In 1917, still in the middle of the war, this conflict temporarily brought a surprising turnaround: the Entente banned the export of cotton products to Germany, but not the export of embroidery. The exporters of textile fabrics reacted by embroidering all export textiles in some way and thus selling them as embroidery. A year later, the sale of embroidery to Germany was banned, which also meant the end of the brief boom.

The last small upswing took place in 1919 after the end of the war, when the reconstruction in the war countries caused demand to rise again for a short time. With the beginning of the global economic crisis , the heyday of St. Gallen embroidery came to an end.

The population development in the city of St. Gallen is often cited as the most striking effect of the following crisis . 1910–1930 the resident population fell from 75,482 to 64,079 due to emigration as a result of unemployment . Although embroidery exports increased again for a short time after the war, the time of the greatest economic crisis for the city began in 1920 at the latest. Between 1920 and 1937 the number of embroidery machines fell from over 13,000 to less than 2,000. In 1929 the Swiss government subsidized a dismantling campaign for ship embroidery machines. Since 1905, the number of employees in the embroidery industry has decreased by 65%. In 1940 only 850 hand embroidery machines, 350 ship embroidery machines and 522 automatic embroidery machines were still in working order, the utilization rate was far less.

The embroidery export reached its absolute low in 1935 with 640 tons of goods (compared to 5,899 tons in 1913). By 1937, however, embroidery export sales rose again to over 20 million Swiss francs for the first time. The majority of the 97 industrial companies newly opened in and around St. Gallen were active in the textile industry.

post war period

The crisis in the textile industry hit all of Eastern Switzerland hard. There were hardly any alternative industries, so the embroiderers remained unemployed. The labor market only eased somewhat in the economic upswing of the 50s and 60s, when other branches of industry were slowly able to establish themselves in Eastern Switzerland. The attempts to revive the embroidery industry showed that the development of more and more new automatic embroidery models made embroidery very capital-intensive, making home embroidery practically impossible. In the 1970s, automatic embroidery machines cost around CHF 750,000, while a hand embroidery machine was still available for a few hundred Swiss francs at the turn of the century, 1899/1900.

The number of those employed in the embroidery industry slowly increased again at first. While in 1941 a total of 4962 people were still employed in embroidery in the cantons of St. Gallen, Appenzell Innerrhoden , Appenzell Ausserrhoden and Thurgau, in 1960 the figure was 7,04. As a result of increasing automation, the number of employees fell back to 5,951 in 1970. The areas of Appenzell Ausserrhoden , which are particularly dependent on embroidery, had not yet fully recovered towards the end of the 20th century.

working conditions

Home work

While embroidery was predominantly or practically exclusively women's work at the time of home handicrafts , this changed suddenly with the introduction of embroidery machines. Working on machines was decidedly a man's job, but the woman was still employed as an assistant; she took care of replacing broken needles and threading them when the thread ran out. Did traditional historiography emphasize the advantages of home work mentioned above - in 1877, for example, Dr. Wagner from the Swiss non-profit society referred to factory work: "The greatest misery of our time is the dissolution of the family" - this is how it is judged more critically today. Firstly, the wages for home workers were sometimes very poor and, secondly, children and grandparents often had to work on the embroidery machine in order to provide for the family. The majority of homeworkers lived in their own house with a good quality of living, but this often did not apply to the workspaces, as these were sometimes set up in damp, poorly ventilated and insufficiently heated rooms.

The interaction between the textile industry and agriculture was always highlighted . The farmers - according to the ideal - would use their free time productively, have variety, and could improve their meager income. It is undisputed that this was true for some farms. However, the competition among stickers was very fierce and the machines were often burdened with high credits, so that there was usually little time left for agriculture. The rough working method of a farmer was also not conducive to the fine work necessary in the embroidery, so that many of these agricultural embroidery companies could only do rough work. An exception was the pure hand embroidery carried out by women, as it was mainly carried out in Appenzell Innerrhoden until well into the 20th century.

Wages and working hours

In the heyday, sticker wages were acceptable, especially for self-employed homeworkers. This even though the Ferggers and the exporters tried to maximize their own profits by claiming wage deductions for (alleged) goods defects. It was worse for the auxiliary workers, who often only lived from hand to mouth.

The working hours were very long, especially when there was great demand. The embroidery, which was almost exclusively dependent on export, was very susceptible to crises. As soon as sales stalled, sticker wages fell rapidly in some cases. Since the stickers are described as self-employed, very proud workers, according to their job description, they usually did not complain about lower incomes. They didn't show anything on their appearance either, because they preferred to save on their food instead of their clothes.

Health hazards

The daily working time of the stickers was between 10 and 14 hours, which often led to health problems due to overloading the muscles - most embroidery machines could still be operated by hand - as well as anemia or pulmonary tuberculosis . The position of the sticker in front of the pantograph was extremely unhealthy from an ergonomic point of view - the sticker chest was partially severely damaged and its spine was bent. 25% of all stickers were already at the screening classified as unfit for service.

|

Infant mortality in the canton of St. Gallen Number of deaths in the first year of life per 1,000 live births |

||

| period | St. Gallen | Switzerland |

|---|---|---|

| 1867-1870 | 272 | 210 |

| 1871-1875 | 252 | 198 |

| 1876-1880 | 232 | 188 |

| 1881-1885 | 209 | 171 |

| 1886-1890 | 182 | 159 |

| 1891-1895 | 164 | 158 |

| 1896-1900 | 145 | 143 |

| 1901-1905 | 149 | 134 |

| 1906-1910 | 128 | 115 |

| 1911-1914 | 111 | 101 |

| 1936-1940 | 45 | 45 |

| 1951-1955 | 27 | 29 |

| 1988-1991 | 7th | 7th |

The infant mortality rate was St. Gallen in the second half of the 19th century extraordinarily high in the northern, industrialized districts of the Canton (see table). One of the reasons for this was that the women should be reintegrated into the work process as soon as possible after the birth of the children, because their work was needed. The children were often weaned too early , which led to gastrointestinal infections , from which infants often died.

Education in hygiene

Various physicians began to counteract the prevailing grievances by providing information in the areas of hygiene , nutritional advice and child care - with measurable success. Through the hygiene training, especially of the teachers, and the hiring of special school doctors to monitor them, the hygiene awareness of the population was sustainably improved. With newspaper articles, guides, lectures and courses, the mothers were brought up to the bourgeois ideal, according to which it is a "holy profession" to be a housewife and mother and to put oneself in the service of their "dream child". At the beginning of the 20th century, this ideal was opposed by the harsh working conditions in the textile industry, which is why doctors such as B. Frida Imboden-Kaiser for the establishment of advice centers for expectant mothers and for baby care.

In addition to external cleanliness, the doctors also paid attention to “stomach hygiene”, ie nutrition. Dairy products and meat were touted as healthy products, luxury foods and carbohydrates fell into disrepute. This was in favor of agriculture, which thus increasingly concentrated on livestock farming. The hitherto completely normal consumption of sometimes large amounts of alcohol was also combated.

The embroidery today

Although embroidery is no longer as important for the region as it was at the beginning of the last century, it is still an economic factor today. Embroidery machine factories such as Benninger AG in particular are among the larger employers in the region. Big names like Pierre Cardin , Chanel , Christian Dior , Giorgio Armani , Emanuel Ungaro , Hubert de Givenchy , Christian Lacroix , Nina Ricci , Lecoanet Hemant and Yves Saint Laurent use lace from St. Gallen. There is hardly a major fashion show in the world that does without the presentation of corresponding creations.

Effects on the city of St. Gallen

Today there are only a few companies that produce St. Gallen embroidery for women around the world . Practically only computer-controlled embroidery machines are used. In Eastern Switzerland, the time of hand embroidery is finally over. In 2010 there was only one hand sticker that used his machine (built around 1870) professionally.

In the "Gallusstadt" itself, embroidery products are presented alongside the traditional fashion shows at the CSIO and at the St. Gallen spring and trend fair OFFA at the St. Gallen Children's Festival . This festival owes much of its importance and character to embroidery.

The great flowering of embroidery and the wealth associated with it also had a lasting impact on the cityscape of St. Gallen. From today's perspective, one can say that the city was built around 1920 - apart from the later expanded outer quarters. The Art Nouveau and Neo-Renaissance buildings from the period between 1880 and 1930 define the image of the industrial districts built around the old town during this period . The names of these former business buildings give an idea of the former importance of world trade for the city: Pacific , Oceanic , Atlantic , Chicago , Britannia , Washington , Florida ...

See also

swell

- Eric Häusler, Caspar Meili: Swiss Embroidery. Success and crisis of the Swiss embroidery industry 1865-1929 . Published by the Historical Association of the Canton of St.Gallen, St. Gallen 2015, ISSN 0257-6198. Link to the PDF at: http://www.hvsg.ch/pdf/neujahrsblaetter/hvsg_neujahrsblatt_2015.pdf

- Ernst Ehrenzeller: History of the City of St. Gallen . Edited by the Walter and Serena Spühl Foundation. VGS Verlagsgemeinschaft, St. Gallen 1988, ISBN 3-7291-1047-0 .

- Peter Röllin (concept): The time of embroidery, culture and art in St. Gallen 1870–1930 . VGS Verlagsgemeinschaft, St. Gallen 1989, ISBN 3-7291-1052-7 .

- Max Lemmenmeier: embroidery blossom . In: Sankt Galler Geschichte 2003, Volume 6, Die Zeit des Kantons 1861-1914 . Office for Culture of the Canton of St. Gallen, St. Gallen 2003, ISBN 3-908048-43-5 .

- Albert Tanner: The boat flies, the engine roars. Weavers, stickers and manufacturers in Eastern Switzerland . Union Publishing House; Zurich 1985; ISBN 3-293-00084-3 .

- The Canton of St. Gallen; Landscape community home; Office for Cultural Maintenance of the Canton of St. Gallen; ISBN 3-85819-112-0

- Ernest Iklé: La Broderie mécanique . Edition A. Calavas Paris 1931, text available on the Internet under Ernest Iklé.

- Swiss pioneers in business and technology, Volume 15 Isaak Gröbli, inventor of the boat embroidery machine . Association for Economic History Studies, 8006 Zurich 1964.

- Friedrich Schöner: Tips, encyclopedia of high technology . VEB Fachbuchverlag Leipzig 1980.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ehrenzeller, page 406

- ^ Tanner, page 186

- ↑ Source: Federal Population Censuses, in: Tanner, p. 204

- ↑ Lemmenmeier, page 12

- ↑ St. Galler Tagblatt of January 22, 2009: In St. Galler Spitze ( Memento of April 14, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Markus Wehrli: The last hand stickers (PDF; 506 kB) St. Galler Tagblatt . April 24, 2010. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved July 28, 2010.