Star of Bethlehem

The star of Bethlehem (also: Dreikönigsstern , Poinsettia or Star of the Magi ) is a celestial phenomenon which, according to the Gospel of Matthew, led magicians or wise men to the place of birth of Jesus Christ ( Mt 2,1.9 EU ):

“When Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea at the time of King Herod , magicians from the east came to Jerusalem and asked: Where is the newborn King of the Jews? We have seen his star rise and have come to pay homage to him. … And the star that they had seen rise went before them to the place where the child was; he stopped there. "

Christians celebrate this episode on the Feast of Epiphany or Epiphany .

Since late antiquity , astronomical and astrological theories have related the “star of Bethlehem” to various celestial phenomena that were visible before the turn of the ages, in order to more precisely date the birth of Jesus:

- to Halley's Comet (12-11 v. Chr.)

- a great conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in the constellation Pisces (7 BC),

- a complex constellation of the sun , Jupiter, Venus and the moon in the constellation Aries (6 BC),

- an unknown other comet or nova (5 or 4 BC) or

- two different conjunctions of Venus and Jupiter (3–2 BC).

Due to specific objections, none of these explanations is scientifically recognized.

Antique background

Special celestial phenomena were in many civilizations of antiquity related to important historical events. In the great empires of ancient Egypt , Mesopotamia , Persia and the media , “astronomy” had a central, state-preserving tradition and function. No distinction has yet been made between star interpretation (astrology) and star observation (astronomy). In Greek philosophy , too , the observation of the starry sky was essential for the metaphysical explanation of the world ( cosmology ).

The Judaism distanced himself on ancient astronomy and forbade the worship of stars as deities (u. A. Deut 4.19 EU ). Nevertheless, authors of the Bible also took celestial phenomena as references to special historical events. In biblical prophecy, however, they were mostly signs of coming calamity. For example, in the context of the announced final judgment, stars should “fall from heaven” ( Mk 13.25 EU ) or “darken” ( Joel 4.15 EU ).

Comet theories

According to Diodorus of Sicily (1st century BC) the Babylonians or Chaldeans were able to observe comets and calculate their return. According to a legend, Pythagoras of Samos , whose teachings were influenced by Egyptian and Persian knowledge, taught: Comets are celestial bodies that have a closed circular path, i.e. that become visible again at regular time intervals. According to the Roman author Seneca , people in the ancient empires were disappointed when comets did not return, so predictions about them turned out to be wrong.

The Christian theology of the second century, which was influenced by Hellenism and Greek metaphysics began with the search for the Star of Bethlehem. Origen (185 to approx. 253), theologian from the Hellenistic school of Alexandria (Egypt) and head of the theological school of Caesarea , was probably one of the first to be of the opinion that the star of Bethlehem was a comet because “when it entered, it was a large one Events and tremendous changes on earth such stars appear ”and, according to the Stoic Chairemon of Alexandria,“ sometimes appeared when happy events occurred ”.

Since the beginning of the 14th century, artists have depicted the star of Bethlehem as a comet: for example, as one of the first Giotto di Bondone from Florence , after he had observed Halley's comet in 1301 , of which ancient sources report quite often. Impressed by this, he painted this two years later on the fresco “Adoration of the Magi” in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua as the Star of Bethlehem.

A Chinese and a Korean source each reported a comet appearance in the year 5 or 4 BC. Both reports may refer to the same event, although the Chinese report would contain a dating error. It is believed to be a nova.

The objection to the comet theory:

- Halley's Comet was between October 12 BC. BC and February 11 BC Visible, it was closest to earth on December 29, 12 BC. According to the Gregorian calendar . The birth of Jesus, on the other hand, is between 7 and 4 BC. BC (death of Herod).

- Comets are irregularly appearing celestial bodies which, according to popular belief about the birth of Christ, were usually associated with calamity, not with salvation.

- The wise men from the east could not have known that this particular comet was related to the birth of a particular king in Israel or Judah.

- The appearance of a comet would have been noticed not only by the wise, but also by many others. However, we are not aware of any extrabiblical traditions.

- A comet would not have marked an exact location and would not have stopped at a certain point.

Conjunction theories

Johannes Kepler (from 1604)

Since the Sassanid Empire in the 3rd century, astrologers have seen a conjunction (encounter) between the planets Jupiter and Saturn as portents of important historical events, such as a new age, a new dynasty, the birth of a prophet or a just king. Jewish scholars such as Māshā'allāh ibn Atharī , Abraham Ibn Esra and Levi ben Gershon followed this basic assumption. Some of their predictions were related to the birth of the Messiah in Jewish messianism .

The astronomer Johannes Kepler was familiar with such calculations. In December 1603 he observed a conjunction between Jupiter and Saturn in the morning sky in the constellation Serpent Bearer. In the autumn of 1604, the planet Mars joined the two planets in the evening sky. From October 9, 1604, supernova 1604 lit up in the same constellation at a distance of more than 9 degrees . Kepler observed it from October 17, 1604 in the "fiery triangle" of the zodiac signs Aries, Leo and Sagittarius, when it reached an apparent brightness of −2.5 m and thus became the brightest point of light in the evening sky. He could not explain the phenomenon with the knowledge of the 17th century and therefore assumed that the previous triple conjunction had caused a "new star". From this he concluded that there was a conjunction of Jupiter, Saturn and Mars in 7/6 BC, which was already known at the time. Such a new star also followed. In order to equate this with the star of Bethlehem in Matthew 2 and to move closer to the birth of Jesus, however, he incorrectly dated the triple conjunction to the year 5 BC. Chr .; He dated the birth of Jesus to 4 BC. Chr.

No known chronicle records a celestial phenomenon that can be interpreted as a supernova shortly after that conjunction. In addition, we now know that planetary conjunctions and supernovae are not causally connected. In this respect, Kepler's theory was a mistake.

Konradin Ferrari d'Occhieppo (from 1964)

The astronomer and astronomy historian Konradin Ferrari d'Occhieppo has since 1964 pointed out in several publications the very rare triple Jupiter-Saturn conjunction in the sign of Pisces, which was already noted by Kepler. This seemed to fit in well with the approximate time period Jesus was born. According to d'Occhieppo, a Babylonian astronomer had to understand such a conjunction as a reference to an event in Israel (Judea), because Jupiter was the star of the Babylonian god Marduk , while Saturn was considered the planet of the Jewish people. The western part of the fish symbol stood for Palestine, among other things. From this Babylonian astronomers could have concluded: King star (Jupiter) + Israel protector (Saturn) = "In the west (constellation of Pisces) a mighty king was born."

The three conjunctions occurred months apart, so that there was enough time for a journey from Babylon to Judea. D'Occhieppo referred to the expression "We saw his star rise" when he observed the pair of planets standing close together in the darkening evening sky around September 15, 7 BC. Around. At that time the magicians set out for Jerusalem. On November 12th 7 BC BC, shortly after sunset, they had the planets Jupiter and Saturn right in front of their eyes at dusk as they rode south from Jerusalem to Bethlehem, only about ten kilometers away. Mt 2:10 refers to this specific point in time: “When they saw the star, they were delighted.” Jupiter was 15 times brighter than Saturn at the time of the evening sunrise and had a special reputation as a royal star among astrologers. He is the star mentioned here.

After the onset of astronomical twilight, the astrologers would have seen the pair of planets at the top of the zodiacal light cone on November 12th . It looked as if the light was emanating from this pair of planets. During the hours that followed, the axis of the light cone pointed steadily to the Bethlehem in front of them, the houses of which stood out against the zodiacal light like a silhouette. This would have given them the impression that the planets - despite the continuing rotation of the starry sky - stopped over the place where the child was. It can therefore be assumed that they found Jesus' birthplace on this date. It doesn't really depend on the three conjunctions of the two planets, but rather that they stood still very close together for the first time in 854 years in the constellation of Pisces and thus pointed to an unusual event.

D'Occhieppo regards Mt 2: 1–12 as a written eyewitness report of the wise men or one of their companions because of the details of the content. It was presented to Matthew, who copied it. As a result, he translates the text quoted above as follows:

“When Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea in the days of King Herod, behold, magicians came from the rising (from the east: magoi apo anatolón, απο ανατολων) to Jerusalem. They asked: Where is the newborn King of the Jews? We saw his star in the rising (Greek: εν τη ανατολη) and have come to pay homage to him humbly. […] And, behold, the star that they had seen in the rise moved ahead of them until it stopped while walking above where the child was. When they saw the star, they were very happy with great joy. "

This conjunction theory is supported by other astronomers, such as Theodor Schmidt-Kaler , who examined the magician's pericope for statistical purposes. Its popularity is demonstrated by the fact that it is part of the standard program of planetariums every year at Christmas time .

The following are mentioned as objections:

- A three-time meeting of Jupiter and Saturn rarely occurs and never leads to the merging of both points of light, so that it cannot necessarily be related to the one star named in Mt.

- Matthew uses the Greek word for “star” and not that for “planet” or “planetary constellation”. At that time one could very well distinguish between fixed stars and planets. This objection presupposes that the gospel author knew this distinction.

- Above all, it is doubtful whether Saturn was the cosmic representative of the people of Israel for Babylonian astronomers. Saturn (Akkadian kewan ) was connected to the land of Syria according to the Babylonian interpretation , according to the Greek interpretation with the god Kronos , who in some ancient magic books was equated with the Jewish god YHWH - possibly because of the Jewish Sabbath , which is associated with the "dies Saturni" ( Saturn day, English Saturday) coincided. A seven-day week with planet names as the day name was common among the Babylonians. Nevertheless, the transfer from the planet Saturn to Judaism appears doubtful, since its veneration in the Tanach appears almost as a sign of apostasy from Judaism (Am 5:26). Acts 7:43 reminds us of this.

- Today at least four cuneiform tablets are known, on which the Babylonians recorded the ephemeris (orbits) of planets such as Saturn and Jupiter in 7 BC. Have calculated in advance. Their major conjunction played no role there. It is therefore also doubtful whether the Babylonians attached any importance to it.

Other

Due to the objections to d'Occhieppo's theory, some astronomers researched other conjunctions around the turn of the ages and found other very close conjunctions or overlaps, this time of Jupiter and Venus.

On August 12, 3 BC In BC Venus passed Jupiter in the constellation of Leo at a distance of 0 ° 4 '. In this conjunction, the planets almost seemed to merge with the naked eye. So they could be seen as a common morning star in the twilight. After this meeting with Venus, the “royal” planet Jupiter performed its opposition loop directly above the royal star Regulus , three times coming into close conjunction with the main star of Leo.

On June 17, 2 BC In BC Venus passed the planet Jupiter again, with a minimum distance of only 26 ". This conjunction was also visible in the whole of the Near and Middle East, this time in the western sky at dusk, while the full moon stood over the opposite eastern horizon At the closest distance, the two planets appeared to have merged into one point to the naked eye.The approach had previously been followed for several weeks in the western night sky and was therefore well suited as a signpost from Babylon or Persia.

The symbolic interpretation of these astronomical events is justified especially with Gen 49.9-10 EU :

“A young lion is Judah. You grew up from being robbed, my son. He crouches, lies like a lion, like a lioness. Who dares to scare them away?

The scepter never leaves Judah, the ruler's staff from its feet, until he comes to whom it belongs, to whom the obedience of the peoples is due. "

However, this theory requires that Herod's year of death be postponed to a later date than is usually assumed.

Supernova theory

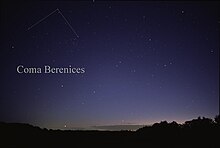

The ancient orientalist Werner Papke assumes that the star of Bethlehem was a supernova that shone in the constellation Haar der Berenike . Extra-biblical mentions of such a supernova or remnants of it in this constellation are unknown or lost. In Babylon, in this region of the starry sky, the figure of a virgin was seen who bore the name "Erua". Papke translates the cuneiform characters of this name as "the one who will give birth to the seed promised in Eden ", in which he sees an allusion to the paradise story in Gen 3:15 EU , and in it in turn the announcement of the birth of a savior. Papke concludes:

“The constellation of the virgin Erua has been around since the third millennium BC at the latest. Was the heavenly sign of a virgin who was to give birth to a son, a male seed, who was already promised in Eden. "

The astrologers mentioned in Mt 2 were followers of Zarathustra's teaching and had known his prediction that a “new star” would mark the birth of a wonderful boy in heaven, whom they should worship. You would also have known Isa 7.14 EU :

"That is why the Lord will give you a sign of his own accord: Look, the virgin will conceive a child, she will give birth to a son and she will give him the name Immanuel (God with us)."

These prophecies brought the astrologers on their way to the Jewish land after the supernova lit up in the middle of the constellation Erua . Papke dates this lighting up on the evening of August 30, 2 BC. In doing so, he refers to Rev 12 EU : In this chapter a constellation of the moon in the constellation Erua is described, which was only possible on the evening of August 30th in the period in question.

When they arrived in Jerusalem, the magicians would have been given Bethlehem as their final destination. From Jerusalem she had the supernova - now standing high in the sky and slowly moving westwards - on the morning of November 28, 2 BC. Chr. Directed to Bethlehem. Once there, the supernova was at the zenith of a very specific house, while it had faded in the brighter morning sky.

Horoscope theory

The US astronomer Michael R. Molnar published a new theory about the star of Bethlehem in 1999: He assumes that the magoi of Mt 2 were astrologers from Mesopotamia (then called “Chaldeans” ) who were based on horoscopes . They did not travel to Judea because of a comet, a conjunction or a nova, but because of a certain, geometrically calculated relation between planets and constellations, which they interpreted as a prediction of the birth of a powerful king in Judea. To this end, he used Greek and Roman horoscopes, which were associated with the birth of kings at that time. The Tetrabiblos of Ptolemy , a compilation former astrological theories, ordered the companies controlled by the Herodians areas, including Judea, the constellation Aries to. According to this, astrologers at the time localized a king's birth under the sign of Aries in Judea. Molnar then looked for a planetary constellation that could have predicted a particularly significant king's birth in Judea:

On April 17th of the year 6 BC Jupiter had its heliacal rise in the constellation Aries, and the sun was "exalted" in it, just like Venus. Astrologers at the time would have interpreted this as a sign of special power. The “rulers of the Aries Trinity” were all gathered in this constellation, the sun and moon had their planetary “servants” nearby. In addition, Jupiter was covered by the moon on the same day. This extraordinary encounter could actually have prompted the astrologers to travel to Judea. That is why they moved to the west, although the statement handed down from Mt 2 "we have seen his star come forth" meant for them the heliacal rising - that is, in the east. It is also understandable that they first moved to Jerusalem, the capital and royal city of Judea. There they may have asked for details from the prophecies to learn more about the possible birthplace of Jesus. The disinterest of the Judeans in astrology at that time explains that no Jewish source at the time noted a celestial phenomenon. Another conjunction occurred on December 19 −6.

Molnar's theory is seen by some authors as a solution to some of the weaknesses of the comet, conjuncture and nova theories. There is no evidence that planetary constellations around the turn of the ages in Mesopotamia were actually interpreted as suggested by the Tetrabiblos from the 2nd century. This work is considered a compendium of the astrology of all Hellenism , since it was created at the library of Alexandria and Ptolemy claimed to include an epoch of 1000 years in it. Even then, it remains to be seen how the rise of Jupiter in the east led the astrologers exactly to the birthplace of Jesus, how their report about it got to an evangelist and why Jewish sources of the time are silent about it.

Bible exegesis

Historians and New Testament scholars who apply historical-critical methods to ancient texts first examine text genres, transmission and editing processes of the NT. They classify the birth stories of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke as later legends with theological statements. They deny that legendary motifs refer to real events at the time and can be used for dating. As a rule, they interpret the star in Mt 2,1.9 as a mythological or symbolic motif of proclamation. In doing so, they reject astronomical-astrological theories on this as unscientific speculations. Because the reports are purely legendary, it is impossible to evaluate them for the dating of Jesus' birth.

The philologist Franz Boll explained the Stern episode in 1917 as a miracle story, which was based on the popular belief of the time: With the birth of a person a star arises which disappears again with his death; the more important this person becomes in his life, the bigger and brighter he is. The phrase "We have seen its star" refers to this popular belief . The word ἀστήρ used here only means “star” in the literature of that time; a "star constellation" or a "constellation" was then called ἄστρον. ἀστήρ relate to ἄστρον like “star” to “star”, which can denote both a single star and a star cluster (for example, seven stars).

This explanation of the star motif is also represented by Hans-Josef Klauck today . He also refers to biblical references in this episode: Bringing precious gifts reminds us of Isa 60,6 and Ps 72,10, which speaks of gifts from foreign kings for Israel's rulers. The rising star could allude to Num 24,17ff EU ("A star will rise from Jacob and a scepter will rise from Israel ..."). The passage heralds a ruler who will finally destroy Israel's enemies all around. Since only King David around 1000 BC Chr. Achieve such lasting victories, some Old Testament scholars take this Balaam saying as Vaticinium ex eventu and date it at the earliest in the time of David.

The expectation of a successor to David, who would free Israel from the hand of its overwhelming enemies and destroy them, was also widespread in Israel at the time of Jesus. The logia source already delimited the image of Jesus. For Ulrich Luz, however , the astrological episode does not contain any direct language analogies to the Baleamperikope . The rising star is only a guide to the Messiah, not a symbol. The legend of the birth stands in contrast to the warlike image of the Messiah: the Messiah does not come to destroy Israel's enemies, but is sought by their wise men and worshiped as their king. In contrast, the then King of the Jews, Herod, who legitimized himself as David's successor, tried to kill the Messiah. Only the " Gentiles " from abroad remind him of the limits of his power and that Mi 5.1 EU had already announced not the capital Jerusalem, but the inconspicuous village of Bethlehem as the birthplace of the Messiah ( Mt 2, 3–20 EU ) .

Exegetes pay special attention to the expression magoi (literally "magician"). Originally used by Jews at the time, it referred to respected sages and scholars, dream interpreters and astrologers, and only later received negative connotations (cheaters, charlatans). In the ancient empire of Persia they belonged to a caste of priests, the Magern , whose advice and interpretation of nature Persian kings sought out for succession planning. The Parthian King Trdat I, for example, traveled to Rome with such magoi in AD 66 to honor Nero with gifts for his accession to the throne; he fell down in front of him and took another way back. In 1902 Albrecht Dieterich assumed that this episode, which was then widely known, had an influence on Mt 2. Many recent exegetes followed this thesis.

Some New Testament scholars have adopted astronomical theories about the star of Bethlehem. Theodor Zahn (1922) considered the magicians in Mt 2, 1–9 to be historical and assumed that they had seen a regular celestial phenomenon. The word for star in Mt 2 ( aster ) was often not differentiated from the word for star (e) ( astron ). August Strobel (1996) related the star to the Jupiter-Saturn conjunction 7/6 BC described by Ferrari de'Occhieppo. Chr .: Herod also saw the star and only asked "the period during which the star shone". Rainer Riesner (1999) recommended d'Occhieppo's theory in accompanying texts for his book. Peter Stuhlmacher (2005) followed d'Occhieppo and Strobel: A conjunction in 7/6 BC BC could have caused the magicians respected in Mesopotamia to move to Jerusalem; but only after the information from Jews about the biblical Messiah prophecy did they find Bethlehem.

See also

- Advent star

- Moravian Star

- Holy Three Kings

- The Star of Bethlehem , a vocal work by Josef Rheinberger

literature

Historical publications

- Oswald Gerhardt: The star of the Messiah; the year of birth and death of Jesus Christ according to astronomical calculations. Deichert, 1922.

astronomy

- Courtney Roberts: The Star of the Magi: The Mystery That Heralded the Coming of Christ. ReadHowYouWant, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4429-6125-8 .

- Wolfgang Habison, Markus Steidl, Doris Vickers, Peter Habison: “The” star of Bethlehem: The phenomenon from an astronomical- historical point of view. Edition Volkshochschule, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-900799-72-5 .

- Konradin Ferrari d'Occhieppo: The star of Bethlehem from an astronomical point of view. Legend or fact? Brunnen, Giessen 4th edition 2003, ISBN 3-7655-9803-8 .

- Mario N. Schulz, Kirsten Straßmann: The star of Bethlehem: The astronomical event 2000 years ago. Kosmos Verlags-GmbH, 2000, ISBN 3-440-08291-1 .

- Mark Kidger: The Star of Bethlehem. Princeton University Press, 1999 books.google

- Dieter B. Herrmann: The star of Bethlehem: Science on the trail of the poinsettia. 2nd edition, Paetec, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-89517-695-8 .

astrology

- Dieter Koch: The star of Bethlehem. Publishing House of Heretic Leaves, 2006, ISBN 3-931806-06-5 .

- Michael R. Molnar: The Star of Bethlehem: The Legacy of the Magi. Rutgers University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8135-2701-5 . books.google

- Thomas Bührke / Michael Molnar: The fairy tale of the star of Bethlehem image of science 12/2000, p. 52 ff.

exegesis

- August Strobel: The contemporary environment of the magician's story Mt 2,1-12. In: Wolfgang Haase, Hildegard Temporini (Hrsg.): Rise and decline of the Roman world . Part II (Principat), Vol. 20/2. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1987, pp. 1083-1099.

- August Strobel: The Star of Bethlehem. A light in our time? 2nd edition, Flacius-Verlag, Fürth 1985, ISBN 3-924022-13-5 .

- Christoph Wrembeck: Quirinius, the tax and the star. Topos Plus publishing house, 2006, ISBN 3-7867-8612-7 .

Stories and games

- Günter C. Körner: Star of Bethlehem: Novellistic prose. Brain-Data-Verlag, 1988, ISBN 3-9801777-0-X .

- Annegret Strobel: The Star of Bethlehem: A Christmas Game. Deutscher Theaterverlag, 2005, ISBN 3-7695-3060-8 .

- Konstantin K. Vaginov : The Star of Bethlehem. Friedenauer Presse, 1992, ISBN 3-921592-71-2 .

- Johannes Pflaum : The Star of Bethlehem. Johannis, 2009, ISBN 978-3-501-19738-7 .

- Karin Wolf, Thomas Wolf, Dagmar Zierold: Star over Bethlehem. Born-Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-87092-324-5 .

- Carl Ernst Köhne: The red star of Bethlehem: from the struggle of the Christian movement with Rome's Caesars; an image of the present that is close to the present. List, 1975, ISBN 3-471-77940-X .

- The star over Bethlehem. ArsEdition, 2006, ISBN 3-7607-7906-9 .

- Reinhard Marheinecke: Star over Bethlehem. R. Marheinecke, 2008, ISBN 978-3-932053-32-0 .

- Rolf Krenzer, Siegfried Fietz: Star of Bethlehem lamp: The Christmas story tells. Patmos, 1989, ISBN 3-491-79402-1 .

Web links

- Extensive (English-language) bibliography on the subject , compiled by the Faculteit Natuur en Sterrenkunde - Universiteit Utrecht.

- Was there a star of Bethlehem? from the alpha-Centauri television series(approx. 15 minutes). First broadcast on Dec 19, 1999.

- Video Lesch's Kosmos: The Star of Bethlehem (December 19, 2011, 1:20 a.m., 2:48 p.m.) in the ZDFmediathek , accessed on February 9, 2014.

- Dieter B. Herrmann : The Christmas story - The star of Bethlehem from a scientific point of view , 7 parts. Lecture given at Urania (Berlin) , published on Youtube on December 25, 2011

- Hans Zekl: The star of Bethlehem . "Astronews" portal, December 24, 2002

- Dieter Koch: The poinsettia from an astrological and astronomical point of view . Essay on the portal "astrodienst"; Excerpt from Dieter Koch: The Star of Bethlehem . Publishing house of the heretical sheets, Frankfurt am Main, 2006, ISBN 978-3-931806-06-4

- Werner Papke : The Star of Bethlehem: Farewell to old and new fairy tales . Kahal.de, December 26, 2001 (pdf; 593 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gabriele Theuer: The moon god in the religions of Syria-Palestine: With special consideration of KTU 1.24. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2000, ISBN 3-525-53745-X , p. 460.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus: Historical Library. Book 15, chap. 50, paras. 2–3, see Julius Friedrich Wurm: Diodor's von Sizilien historical library. Volume 3, Stuttgart 1838, p. 1368 ; Diodorus Siculus. Library of History (Book XV) @ uchicago.edu, accessed December 9, 2018.

- ↑ Origen (contra Celsum), I. LVIII-LIX; Cape. 58 , chap. 59 @ unifr.ch (P. Koetschau 1926, German); on Chairemon see RE: Chairemon 7 @ wikisource.org and Chaeremon of Alexandria @ en.wikipedia.org, accessed December 9, 2018.

- ↑ Chinese and Babylonian Observations ; on astrosurf.com (Astrosurf - Portail d'Astronomie des astronomes amateurs francophones)

- ^ Calculation program Southern Stars Systems - SkyChart III - , Saratoga, California 95070, United States of America.

- ↑ Eckhart Dietrich: From Pietists to Freethinkers: Inescapable consequence of consistent reflection. 2011, ISBN 978-3-8448-5375-9 , p. 27, footnote 116

- ^ Bernard R. Goldstein, David Pingree: Levi Ben Gerson's Prognostication for the Conjunction of 1345. Amer Philosophical Society, 1990, ISBN 0-87169-806-4 , pp. 1-5

- ^ Johannes Kepler: De Stella Nova in Pede Serpentarii. Frankfurt 1606. Lecture with Sabine Kalff: Political Medicine of the Early Modern Age: The Figure of the Doctor in Italy and England in the Early 17th Century. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-11-032284-2 , p. 125 f.

- ^ Paul and Lesley Murdin: Supernovae. Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition 1985, ISBN 0-521-30038-X , p. 20

- ↑ Heather Couper, Nigel Henbest: The Story of Astronomy: How the universe revealed its secrets. Cassell, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84403-726-1 , p. 35

- ^ Ferrari d'Occhieppo: The Messiasstern from a new astronomical and archaeological point of view. In: Religion - Science - Culture. Quarterly journal of the Vienna Catholic Academy 15 (1964), pp. 3–19; Jupiter and Saturn in the years -125 and -6 according to Babylonian sources. In: Meeting reports of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, math.-nat. Class II / 173 (1965), pp. 343-376; Star of Bethlehem. 1994, p. 132

- ^ Ferrari d'Occhieppo: Star of Bethlehem. 1994, p. 170 f.

- ^ Ferrari d'Occhieppo: Star of Bethlehem. 1994, pp. 38 and 66

- ^ Ferrari d'Occhieppo: Star of Bethlehem. 1994, pp. 52 and 155-157

- ↑ Theodor Schmidt-Kaler: The star and the magicians from the Orient. (PDF; 629 kB)

- ↑ WDR.de, Planet Wissen: The Star of Bethlehem - an unsolved riddle

- ↑ Werner Papke: The Star of Bethlehem: Farewell to old and new fairy tales. P. 7.

- ↑ Werner Papke: The Star of Bethlehem: Farewell to old and new fairy tales. Pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Werner Papke: The Star of Bethlehem: Farewell to old and new fairy tales. P. 9.

- ^ Roger Sinnott: Thoughts on the Star of Bethlehem. Sky and Telescope. 1968, pp. 384-386.

- ↑ a b Hans Zekl: The star of Bethlehem ; on astronews.com on December 24, 2002.

- ^ Frederick A. Larson: The Star of Bethlehem

- ↑ Werner Papke: The Sign of the Messiah (1999; pdf; 186 kB)

- ↑ Werner Papke: The sign of the Messiah. A scientist identifies the star of Bethlehem. Christian literature distribution, Bielefeld 1995, ISBN 3-89397-369-9 , pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Michael R. Molnar: The Star of Bethlehem: The Legacy of the Magi. Rutgers University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8135-2701-5 , pp. 30 f.

- ↑ Ilse Maas-Steinhoff, Joachim Grade: Citizens under the protection of their saints: new contributions to medieval art and urban culture in Soest. Klartext, 2003, ISBN 3-89861-216-3 , p. 83; Bild der Wissenschaft, issues 7-12 , Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2000, p. 413.

- ^ Benson Bobrick: The Fated Sky: Astrology in History. Simon & Schuster, 2006, ISBN 0-7432-6895-4 , p. 50.

- ↑ Example: Carl Philipp Emanuel Nothaft: Dating the Passion: The Life of Jesus and the Emergence of Scientific Chronology (200-1600). Brill Academic Publications, 2011, ISBN 90-04-21219-1 , p. 22.

- ↑ Gerd Theißen , Annette Merz : The historical Jesus: A textbook. 4th edition, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2013, p. 150.

- ↑ Franz Boll: The star of the wise. In: Journal for New Testament Science and the News of Early Christianity 18 (1917/1918), pp. 40–48.

- ^ Hans-Josef Klauck: Religion and Society in Early Christianity. Tübingen 2003, p. 307f.

- ↑ Erich Zenger: Introduction to the Old Testament. Kohlhammer, 6th edition. Stuttgart 2006, p. 119; Werner H. Schmidt: Old Testament Faith in its History. Neukirchener Verlag, 4th edition. Neukirchen-Vluyn 1982, p. 209.

- ↑ Ulrich Wilckens: Theology of the New Testament. Volume 1, part 4. Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2005, ISBN 3-7887-2092-1 , p. 117.

- ↑ Ulrich Luz: The Gospel according to Matthew , Volume I / 1 (= Evangelical-Catholic Commentary on the New Testament, 1/1). Patmos, 2002, ISBN 3-545-23135-6 , p. 115.

- ↑ Thomas Holtmann: The Magi from the East and the Star: Mt 2: 1–12 in the context of early Christian traditions. Elwert, 2005, ISBN 3-7708-1275-1 , p. 116.

- ^ Albrecht Dieterich: The wise men from the Orient. In: Journal for New Testament Science and the Knowledge of Early Christianity III (1902), pp. 1–14, 9, digitized .

- ^ Hans-Josef Klauck: Religion and Society in Early Christianity. Tübingen 2003, p. 307 and note 31

- ↑ Theodor Zahn: The Gospel of Matthew (Commentary on the New Testament; 1). Leipzig, Erlangen 1922 (reprint Wuppertal 1984), pp. 89-105; P. 93, fn. 76.

- ↑ August Strobel: World Year…. P. 1083 f .; see also August Strobel: Stern von Bethlehem , in: Das große Bibellexikon, 1996, Vol. 5, pp. 2300–2302.

- ^ Ferrari d'Occhieppo: Star of Bethlehem. 3rd edition, Giessen 1999, pp. 5-7 and pp. 198-202.

- ↑ Peter Stuhlmacher: The Birth of Immanuel. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, pp. 78–80.