Operation punch

| date | February 18 to March 3, 1918 |

|---|---|

| place | Ukraine , Belarus , Baltic States , Southwest Russia |

| output | Victory of the Central Powers |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

Eastern Front (1914-1918)

1914

East Prussian operation ( Stallupönen , Gumbinnen , Tannenberg , Masurian Lakes ) - Galicia ( Kraśnik , Komarów , Gnila Lipa , Lemberg ,

Rawa Ruska ) - Przemyśl - Vistula - Krakow - Łódź - Limanowa - Lapanow - Carpathians

1915

Humin - Mazury - Zwinin - Przasnysz - Gorlice-Tarnów - Bug Offensive - Narew Offensive - Great Retreat - Novogeorgiewsk - Rovno - Swenziany Offensive

1916

Lake Narach - Brusilov offensive - Baranovichi offensive

1917

Aa - Kerensky offensive ( Zborów ) - Tarnopol offensive - Riga - Albion company

1918

Operation Punch

As operation faustschlag (also: company punch ) one is major offensive of the Central Powers in World War I referred to with a focus on southern sector of the Eastern Front on 18 February 1918 as a result of the failed peace negotiations with Soviet Russia began. The troops of Soviet Russia, which consisted largely of remnants of the army of the tsarist empire and armed peasants, were unable to offer any significant resistance to the offensive and were quickly pushed back. Thus a peace treaty with the Central Powers became imperative for the still young revolutionary Soviet Russia.

background

After the October Revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks, the new leadership of Russia, concluded an armistice with the Central Powers in December 1917 and entered into peace negotiations in Brest-Litovsk . The negotiations were deliberately held back by the Soviet negotiators in order to gain time to revolutionize the Western European masses. The leadership of the Bolsheviks was divided as to how to proceed with the Central Powers. Only a small part of the party was in favor of peace at any price. The small group who wanted to accept a dictated peace also included Lenin , who demanded an immediate peace in the event of a German ultimatum. He believed that a respite was essential in order to consolidate the Bolsheviks' power in the interior. According to the People's Commissar for Defense Krylenko, the Russian army had lost all combat strength . Most of the Bolsheviks around Bukharin , however, considered it unacceptable to cede further parts of the former empire to the “imperialists” and advocated the continuation of the war under revolutionary auspices, if necessary as partisan struggle . In order to satisfy both sides, the Soviet Russian negotiator, Trotsky , spoke out in the negotiations with the German Reich and Austria-Hungary that the Communists wanted neither peace nor war with the Central Powers. After the peace of bread with Ukraine and a German ultimatum to accept the peace conditions, he left the negotiations on February 10, 1918 with a scandal.

In Germany there was at first disagreement about the counteraction to be taken. While politicians such as the State Secretary in the Foreign Office Richard von Kühlmann advised patience because the population would not understand a resumption of the fighting, the military in the Supreme Army Command (OHL) advised Erich Ludendorff Kaiser Wilhelm II to react immediately and to eliminate it Bolshevik rule as a source of unrest. On February 13th, at a Privy Council in Bad Homburg, both views clashed, with Wilhelm II following the judgment of his military advisers. The commission headed by Wilhelm von Mirbach-Harff in Russia was ordered back and the Soviet government was informed of the resumption of fighting on February 18.

offensive

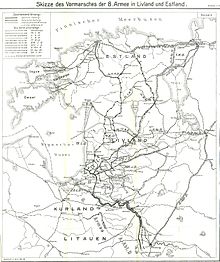

The main aim of the OHL was to occupy the agriculturally and economically important Ukraine in the south of the Eastern Front. The company tied almost a million soldiers who advanced in less than two weeks in a large arc - from the Baltic States via Belarus to eastern Ukraine. However, the most powerful of the German units on the Eastern Front had already been withdrawn to the Western Front for the spring offensive .

course

The offensive began on February 18, 1918 with around 50 German divisions . It ran in three directions: to Narva in the northeast, to Smolensk in the east and to Kiev in the southeast. There was hardly any resistance to the German troops, so their advance was very rapid. The troops of the Central Powers made use of the Russian rail network. After just one day it was possible to take Dünaburg on the north route . Shortly afterwards Pskov followed , and on February 28th Narva.

Minsk , which on February 18 was 250 kilometers away from the front and only weakly defended , was captured after only three days (eastern route). On February 24th, the important district town of Zhytomyr fell in the northwest of today's Ukraine (southeast route). On March 3, the Ukrainian capital Kiev fell into German hands after a brief siege. The troops of the Central Powers were able to cover around 500 kilometers in just under two weeks, which corresponds to a daily workload of 35 kilometers. The advance continued even after the Soviet relent on February 24th and the arrival of a new Soviet negotiating delegation in Brest-Litovsk.

Emperor Karl I initially refused to consent to the participation of the Austro-Hungarian army , but at the urging of General Staff Chief Arz von Straussenburg , who feared a loss of influence in the Ukraine , agreed on February 24, 1918. On February 28, Austrian troops finally started moving towards Odessa and captured it on March 13.

After German planes bombed Petrograd , Lenin ordered the government to move to Moscow in early March 1918. On April 18, Kharkov , the center of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic in eastern Ukraine, was captured .

consequences

In view of the rapid advance of the Central Powers and the great loss of territory in Belarus and the Ukraine , the Bolsheviks saw themselves forced to sign the dictated peace of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918. Soviet Russia was already immersed in the revolutionary whirlpool when the offensive began. The few troops of the former tsarist empire that were still at the front were tired of war and too poorly equipped to be able to stop the troops of the Central Powers. In addition, the communist leadership in Moscow and Petrograd hastily sent armed peasants to the front and tried to counter the Central Powers with everything that was militarily available. The fact that these untrained, irregular auxiliaries were not very successful and were often wiped out as a result, further weakened the defensive strength and morale of the Russians.

An important consequence of the offensive was that the German occupation served as a kind of catalyst between the individual conflicting parties in revolutionary Soviet Russia. The power of the Bolsheviks was broken in all areas of the former tsarist empire invaded by German troops. The occupation gave new potential to the factions that had just been marginalized during the consolidation phase of the Bolsheviks. During the German advance on the Crimean peninsula , the Muslim Crimean Tatars were raised . This culminated in the assassination of the council of people's commissars of the local Soviet republic. Nationalism revived in Ukraine after the invasion of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and German troops. During the conquest of Zhytomyr on February 24, 1918, the invaders received help from Ukrainian railway workers and shortly after the conquest of the Ukrainian capital, the Central Na Rada returned to parliament.

The German occupation had more extensive consequences in the Baltic States. In Estonia the popularity of the Bolsheviks was very low and the revolutionaries failed to build a political organization under the German occupation that could have changed this. After the Estonian victory against the Baltic Landwehr in the Battle of Cēsis in June 1919, a land reform followed in October 1919 in which Baltic German landowners were expropriated and their land was distributed to small farmers. A government was formed under the leadership of Estonian Social Democrats; this was also able to assert itself militarily in the ensuing war of freedom against Soviet Russia.

See also

literature

- William C. Fuller Jr.: The Eastern Front. In: Jay Winter, Geoffrey Parker, Mary R. Habeck: The Great War and the twentieth century. Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2000, ISBN 0-300-08154-5 .

- Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius : Land of War in the East. Conquest, colonization and military rule in the First World War 1914–1918. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-930908-81-6 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Richard Pipes : The Russian Revolution, Volume 2: Die Macht der Bolschewiki , Rowohlt, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-87134-025-1 , p. 415 ff.

- ↑ Klaus Wiegrefe , Florian Altenhöner, Heiko Buschke, Anika Zeller: Russia has never been more for sale. In: Der Spiegel. December 17, 2007, accessed November 18, 2014 .

- ↑ Gerhard Hirschfeld , Gerd Krumeich , Irina Renz (eds.): Encyclopedia First World War. Schöningh, Paderborn 2003, ISBN 3-506-73913-1 , p. 266.

- ^ David R. Woodward: World War I Almanac . Infobase Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4381-1896-3 . P. 295ff.

- ^ Elisabeth Kovács: The fall or salvation of the Danube monarchy? Volume 1: Emperor and King Charles I (IV.) And the reorganization of Central Europe (1916–1922). Böhlau, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-205-77237-7 , p. 310.