Virginia Hall

Virginia Hall Goillot DSC Croix de guerre MBE (born April 6, 1906 in Baltimore , † July 8, 1982 in Rockville , Maryland ) was an American secret agent during the Second World War . She was employed by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

As the first female agent of the SOE, Hall with only one leg went to France in August 1941 and created the Heckler network in Lyon . In 1942 she fled the Germans to Spain , but returned to France in 1944 to continue supporting the French resistance . After the war she was awarded medals by several states.

biography

Early years

Virginia Hall was the daughter of Barbara Virginia Hammel and Edwin Lee Hall, the father was a banker and entrepreneur. She had a brother four years her senior. The affluent family was well-to-do in Baltimore , and the mother tried to arrange an advantageous match for Virginia, known as Dindy . Virginia, however, was a tomboy who preferred to hike or go hunting with her father . She attended Radcliffe Women's College in Cambridge , Massachusetts and Barnard College in New York , where she studied French , Italian and German . She also attended George Washington University in Washington, DC to study French and economics . For further studies she traveled to Europe and studied in France, Germany and Austria.

In 1931 Hall got a job in the office of the consulate of the US embassy in Warsaw . A few months later she was transferred to Smyrna , now Izmir , in Turkey . The following year, she accidentally shot herself in the left foot while hunting. Her leg had to be amputated below the knee , and she was given a three-pound prosthesis made of painted wood with an aluminum base , which she named Cuthbert . She then continued to work as a consular clerk in Venice and Tallinn . She applied several times for the diplomatic service within the United States Information Service , which, however, rarely hired women. In 1937 it was rejected again, this time due to an alleged handicap rule . A complaint to President Franklin D. Roosevelt , who was himself physically disabled, went unanswered, and in March 1939 she resigned.

In February 1940, shortly after the outbreak of World War II , Virginia Hall became an ambulance driver for the Service de santé des armées of the French army . After the occupation of France by the Wehrmacht in June 1940, she came to Spain . There she met an employee of the Secret Intelligence Service , who recommended her to Nicolas Bodington , the head of the F section of the young British secret service SOE (Special Operations Executive).

Second World War

From April 1941 Hall worked for the SOE and, after training, traveled to Lyon in the unoccupied Vichy in August 1941 . She posed as a reporter for the New York Post and dressed very inconspicuously; often she changed her appearance with disguises and make-up . She founded her own network of agents, called Heckler , which included a gynecologist and the boss of the local brothel , which was regularly visited by German officers, and operated under various aliases. In October 1941, she stayed away from a meeting of SOE agents in Marseille , which was then stormed by the French police. Twelve agents were arrested. Hall remained one of the few SOE agents still in France and the only one who kept contact with London. George Whittinghill, an American diplomat in Lyon, allowed her to send reports and letters to London with his diplomatic baggage. In addition, with the help of her French confidante, Virginia Hall hid downed Allied pilots who had been shot down and helped them get to Spain.

In July 1942, the Virginia Hall network managed to free the twelve agents arrested in Marseille from Mauzac prison . The wife of one of the prisoners had brought her husband cans of sardines , from which the latter had made a key for the prison door. Hall provided safe hiding places, cars, and other helpers. On July 15, 1942, the agents managed to escape and with the help of Hall they were able to return to England via Spain; some of them took on important roles in the SOE.

In response to this liberation action, the German Abwehr sent around 500 agents to Vichy and began to infiltrate the French Resistance and the SOE groups . She concentrated on Lyon, the center of resistance. Virginia Hall could no longer rely on its informers with the French police because of this growing pressure.

The Luxembourg priest and member of the Abwehr, Robert Alesch , had previously succeeded in infiltrating the Réseau Gloria resistance cell , which included Samuel Beckett , whereupon its leader was arrested in August 1942. Twelve people were executed and over 80 deported to concentration camps. Although Virginia Hall was suspicious of him, Alesch managed to join her group and send (false) messages to London on her behalf. He was sentenced to death in France after the war and executed in 1949.

On November 7, 1942, the US consulate in Lyon informed Virginia Hall that the British-American invasion of French North Africa was imminent. In response to the invasion the next day, the Wehrmacht occupied Vichy. Klaus Barbie became Gestapo chief in Lyon . Barbie, who never found out Hall's real name or nationality, is reported to have said he would do anything to get his hands on "that limping Canadian bitch." He had a bounty put on them and wanted posters distributed.

However, Hall had already fled Lyon, which she had not even informed her closest contacts. She took the train to Perpignan , from where, with the help of a guide, she crossed a 2300-meter-high snow-covered pass in the Pyrenees despite her bloody stump . Before escaping, she radioed to London that she hoped Cuthbert would not hinder her escape. The SOE man in England radioed back: "If Cuthbert causes problems, eliminate him." On arrival in Spain, she was arrested for illegally crossing the border, but the American embassy arranged for her to be released. For some time she worked for the SOE in Madrid until she returned to London in July 1943.

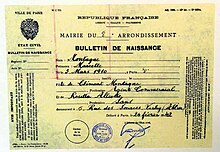

Upon her return, her superiors from the UK SOE refused to send Virginia Hall to France again because it was too dangerous. She then applied to the US secret service OSS. In March 1944 she returned to France; Because of her handicap, she could not jump with a parachute, but was dropped off with the agent Henri Lassot in a boat on the coast near Beg an Fry in Brittany to set up the Saint network . The OSS provided her with forged papers in the name of Marcelle Montagne . Hall, disguised as an old peasant woman with gray hair, was to assist Lassot as a radio operator. The aim of their work was to support the Maquis . Hall, however, quickly separated from Lassot because he was too talkative and a security risk.

From March to July 1944 Virginia Hall stayed in the south of Paris. She organized landing zones for skydivers , safe hiding places, founded and supported resistance groups. An attempt to free German prisoners, including three young men whom Hall referred to as "her boys", failed; the men later perished in the Buchenwald concentration camp . She then supported the resistance of the Maquis in southern France from Le Chambon-sur-Lignon in preparation for Operation Dragoon . Because she was a woman, she had problems asserting herself among the French resistance fighters. However, thanks in part to Hall's organization, the Maquis's departments (around 1,500 men) managed to carry out a series of successful acts of sabotage and finally to push the Germans north as part of the Forces françaises de l'intérieur . On September 22, 1944, Hall and other Allied officers reached Paris; for them the war was over.

After the war and later years

When the war ended, Virginia Hall traveled to Lyon to meet her former comrades-in-arms, many of whom had died during the war years. Her two closest confidants, the brothel owner Germaine Guérin and the gynecologist Jean Rousset, had also been arrested by the German occupiers and deported to concentration camps, but survived. Both were sick and poor. Only Guérin received £ 400 reparation at Hall's instigation .

In 1947 Hall was one of the first women to be hired by the newly founded Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and worked mainly in the USA from a desk, for example to document the influence of communism in Europe and to support resistance groups in Eastern Europe. Her superiors gave her bad reports. A colleague, E. Howard Hunt , said, “You didn't know what to do with her. [...] She was a kind of embarrassment for these CIA types with no combat experience, I mean bureaucrats. ”In 1966, at the age of 60, she retired.

In 1957 Hall married the OSS officer Paul Goillot, whom she met during her time in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and with whom she had lived and worked for years. The couple moved to a farm in Barnesville , where they lived until their death in 1982. Her husband outlived her by five years. She was buried in a Halls family grave in Druid Ridge Cemetery , Pikesville , where her husband is also buried.

Honors and memories

In July 1943, Virginia Hall was quietly appointed Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in London , something that remained unknown for 50 years. In France, Hall was awarded the Croix de guerre . In 2016, a training center was named by the CIA Virginia Hall Expeditionary Center . She was posthumously inducted into the Maryland Women's Hall of Fame in 2019 . Hall's name is on the Tempsford Memorial , which among other things commemorates the secret agents who were active during the Second World War.

In September 1945 the American General William J. Donovan personally presented her with the Distinguished Service Cross for her actions in France . President Harry S. Truman requested a public delivery, but Hall declined because it was still on duty. His reason for the award of the medal: “Miss Hall displayed rare courage, perseverance and ingenuity; her efforts contributed materially to the successful operations of the Resistance Forces in support of the Allied Expeditionary Forces in the liberation of France. ”(“ Miss Hall showed rare courage, perseverance, and ingenuity; her efforts contributed significantly to the successful operations of the Resistance Forces in support of the Allied expeditionary forces in the liberation of France. ”) At the private award ceremony in Donovan's office, only Truman and her mother Barbara Hall were present, but Hall's partner Paul Goillot was not, because her mother disliked this relationship:“ Virginia had not married , no children born. Now she had returned from the war exhausted and, moreover, still dragged this Nobody Paul. And the rebel, who had just commanded a resistance struggle, did not dare to ignore her mother's wishes. "

Because Virginia Hall refused to speak or write about her experiences during World War II, her name was initially forgotten. It was only after her death that interest in her person arose and several books about her appeared. On the occasion of their 100th birthday in 2006, the French and British ambassadors in Washington paid tribute to their achievements. On this occasion, the oil painting Les Marguerites Fleuriront ce Soir by Jeffrey W. Bass, which shows Virginia Hall as a radio operator in a French barn, was unveiled at the French embassy . The title of the picture refers to the text of an encrypted message with which the French program had informed the BBC Hall during the war that material was on its way.

Liberté: A Call to Spy , a feature film about Virginia Hall and other women in the Resistance,premieredin June 2019 at the Edinburgh International Film Festival to mark the 75th anniversary of D-Day . The screenplay was written by Sarah Megan Thomas , who also played Hall in the film, and the director was Lydia Dean Pilcher . A British film based on the book by Sonia Purnell, with Daisy Ridley in the lead role, is being planned (as of 2017); The producer is JJ Abrams .

literature

- Marcus Binney: The Women Who Lived for Danger: The Women Agents of SOE in the Second World War . Hodder & Stoughton, London 2002, ISBN 0-340-81840-9 (English).

- Pierre Fayol: Le Chambon-sur-Lignon sous l'Occupation: 1940-1944: les résistances locales, l'aide interalliée, l'action de Virginia Hall (OSS) . L'Harmattan, London 2000, ISBN 978-2-7384-0801-3 (French).

- Craig Gralley: Hall of Mirrors: Virginia Hall: America's Greatest Spy of WWII . Chrysalis Books, 2019, ISBN 978-1-73354-150-3 (English).

- Vincent Nouzille: L'Espionne. Virginia Hall, Une Americaine in the Guerre . Fayard, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-213-62827-1 (French).

- Judith L. Pearson: The Wolves at the Door: The True Story of America's Greatest Female Spy . The Lyons Press, 2005, ISBN 1-59228-762-X (English).

- Sonia Purnell: A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II . Virago, New York 2019, ISBN 978-0-349-01017-5 (English).

Web links

- Anna Rothenfluh: The American agent who built up the French Resistance. In: watson.ch. August 29, 1944, accessed February 6, 2020 .

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Not Bad for a Girl from Baltimore: The Story of Virginia Hall. In: state.gov. Retrieved February 5, 2020 .

- ↑ Jane Warren: Virginia Hall: The spy the Nazis could never catch. In: express.co.uk. March 30, 2019, accessed February 6, 2020 .

- ^ A b Anna Rothenfluh: The American agent who built up the French Resistance. In: watson.ch. August 29, 1944, accessed February 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 12-21.

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 13-29.

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 39-40, 46-47.

- ↑ Gralley, p. 2. [1]

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 47, 52-53.

- ↑ Purnell, p. 64.

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 113-126.

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 127-137.

- ↑ Teju Cole: Resist, Refuse. In: nytimes.com. September 8, 2018, accessed February 5, 2020 .

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 144-152.

- ↑ a b Gabrielle Jeanine Picabia, chef du réseau Gloria SMH. In: museedelaresistanceenligne.org. Retrieved February 6, 2020 .

- ^ A b Women in Intel: Virginia Hall - Central Intelligence Agency. In: cia.gov. March 21, 2019, accessed February 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Gralley, pp. 3-4. [2]

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 158-159.

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 191-193, p. 197.

- ^ Margaret L. Rossiter: Women in the Resistance . Praeger, New York 1986, p. 102-193 .

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 197-199, 203-206, 209.

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 189, 207-208, 222-223.

- ^ "Activity Report of Virginia Hall (Diane)," F-Section, Heckler, [3] . Accessed February 6, 2020,

- ↑ Rossiter, pp. 196-197.

- ^ Hall, p. 1168. [4]

- ↑ Rossiter, pp. 195-196.

- ^ Purnell, p. 267.

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 281-282.

- ^ Virginia Hall: The Courage and Daring of "The Limping Lady". In: cia.gov. June 29, 2017, accessed February 7, 2020 .

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 257, 291, 294-295, 300-305.

- ↑ Purnell, pp. 307, 311.

- ^ Virginia Hall (1906-1982). In: de.findagrave.com. May 21, 2006, accessed February 6, 2020 .

- ^ Prologue: The Journal of the National Archives. P. 260 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Siegfried Buschschlueter: Late honor. In: deutschlandradio.de. December 12, 2006, accessed February 6, 2020 .

- ^ NPR Choice page. In: npr.org. January 1, 1970, accessed February 6, 2020 .

- ^ Virginia Hall, Maryland Women's Hall of Fame. In: msa.maryland.gov. Retrieved February 6, 2020 .

- ^ Women - Tempsford Memorial. In: tempsfordmemorial.co.uk. Retrieved February 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Purnell, p. 307

- ↑ Ambassadors to honor female WWII spy. In: nbcnews.com. December 11, 2006, accessed February 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Les Marguerites Fleuriront ce Soir. In: cia.gov. June 25, 2008, accessed February 6, 2020 .

- ↑ The B2 Spy Radio (PDF file)

- ↑ AJ Willingham: CIA spy Virginia Hall is about to be everyone's next favorite historical hero. In: cnn.com. April 20, 2019, accessed February 6, 2020 .

- ^ Liberté: A Call to Spy. In: Edinburgh International Film Festival. June 28, 2020, accessed on February 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Oliver Gettell: Daisy Ridley to Play Trailblazing Spy Virginia Hall for Paramount. In: ew.com. January 24, 2017, accessed February 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Georgiana E. Presecky: Daisy Ridley talks 'Ophelia' and upcoming biopic Virginia Hall. In: ff2media.com. July 26, 2019, accessed March 13, 2020 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hall, Virginia |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Goillot, Virginia Hall (married name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American agent |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 6, 1906 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Baltimore |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 8, 1982 |

| Place of death | Rockville , Maryland |