Referendum in Schleswig

In the referendums in Schleswig , on February 10, 1920 and March 14, 1920, two voting zones were held to determine whether Schleswig was a state .

prehistory

Constitutionally, the existing of about 1200 to 1864, Duchy of Schleswig and Jutland Süder a Danish fief , where the Danish king since 1460, both in personal union in his capacity as King ( feudal lord as Duke (Lehnsempfänger or) as a vassal worked). The fact that the duchy was an indirect and not a direct part of the kingdom can also be found in the speech of the then Minister of State Niels Neergaard on reunification on July 11, 1920, in which he expressed that “Southern Jutland is never one in its thousand-year history with Denmark ”. In terms of language and culture, Schleswig and Southern Jutland were largely influenced by Danish. In the Middle Ages, the Danish-speaking area extended as far as a line between Eckernförde - Treene - Husum , where the Danewerk border wall ran, accordingly, in 1920 Neergaard also spoke of the "old Danish southern Jutland". The Eider was established as the German-Danish border river between the Danish King Hemming and Charlemagne as early as 811. However, the unification of Denmark was only realized under Gorm the Elder and his son Harald Blauzahn in the 10th century. In the 12th and 13th centuries the Duchy of Schleswig developed in the south of Jutland, the dukes of which were temporarily provided by the Counts of Holstein , so that from the south a German influence had an economic, but also linguistic and cultural effect. At times, the southernmost part of Schleswig between Schlei and Eider was also under the Roman-German Empire and was known as the Danish Mark or Mark Schleswig.

After the German-Danish War of 1864, the Vienna peace treaty concluded between Prussia, Austria and Denmark dissolved the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg from Danish sovereignty and placed them under joint administration by Prussia and Austria . Before the war, Schleswig as a Danish duchy and Holstein and Lauenburg as members of the German Confederation were part of the entire Danish state . Two years after the war there was a break between the two powers of the German Confederation. In paragraph 5 of the Prague peace treaty of 1866 after the German war Prussia undertook to French pressure towards over England and France, the Danish German-perform in the northern part of the war of 1864 ceded to Prussia Schleswig within six years a referendum on nationality. Denmark was officially notified of this provision. Bismarck let the six years pass and did not comply with this provision, even after Danish warnings to fulfill the contract. In 1878, at the instigation of Bismarck, this North Schleswig clause of the Peace of Prague was repealed in a secret agreement between Germany and Austria before the start of the Berlin Congress . This agreement was not published until six months later, because Austria wanted to avoid making it look as if Germany had done something before the Berlin Congress. Therefore, this agreement was only announced in the Reichsanzeiger on February 4, 1879 . Despite this, Denmark continued to keep the German promise to hold a referendum in North Schleswig . It was not until 1907 that Denmark recognized the demarcation of 1864 as final in the Copenhagen Optanten Treaty .

poll

After the defeat of Germany in the First World War , in which Denmark did not take part, the Versailles Treaty provided for a referendum for the northern areas of Schleswig and defined the voting zones and modalities according to Denmark's wishes.

Two voting zones were designated. In Zone I north of the Clausen Line , voting took place en bloc , which, given the expected overall Danish majority, meant that local border majorities would not be considered for Germany. In the southern zone II, with an expected German majority, a vote was taken one month later, and the results were evaluated on a municipality-by-municipality basis, so that it was possible to add individual municipalities with a Danish majority to Denmark.

Zone I ("North Schleswig")

In the referendum in North Schleswig on February 10, 1920, of 112,515 eligible voters, 25,329 (24.98%) voted for Germany and 75,431 (74.39%) for Denmark; 640 votes cast (0.63%) were invalid.

Zone I consisted of the former administrative districts

-

Hadersleben (Haderslev): 6,585 votes or 16.0% for Germany, 34,653 votes or 84.0% for Denmark, thereof

- City of Hadersleben 3,275 votes or 38.6% for Germany, 5,209 votes or 61.4% for Denmark;

-

Aabenraa (Aabenraa): 6,030 votes or 32.3% for Germany, 12,653 votes or 67.7% for Denmark, thereof

- City of Aabenraa 2,725 votes or 55.1% for Germany, 2,224 votes or 44.9% for Denmark;

-

Sonderburg (Sønderborg): 5,083 votes or 22.9% for Germany, 17,100 votes or 77.1% for Denmark, which

- City of Sonderburg 2,601 votes or 56.2% for Germany, 2,029 votes or 43.8% for Denmark and

- Flecken von Augustenburg 236 votes or 48.0% for Germany, 256 votes or 52.0% for Denmark;

-

Tondern (Tønder), northern part : 7,083 or 40.9% for Germany, 10,223 votes or 59.1% for Denmark, which

- City of Tondern 2,448 votes or 76.5% for Germany, 750 votes or 23.5% for Denmark,

- Flecken Hoyer 581 votes or 72.6% for Germany, 219 votes or 27.4% for Denmark and

- Flecken Lügumkloster 516 votes or 48.8% for Germany, 542 votes or 51.2% for Denmark;

- Flensburg (Flensborg), northern part : 548 votes or 40.6% for Germany, 802 votes or 59.4% for Denmark.

Zone II ("Middle Schleswig")

On March 14, the referendum took place in Zone II, Middle Schleswig (today's northern southern Schleswig) with Flensburg , Niebüll , Föhr , Amrum and Sylt . Of the 70,286 eligible voters, 51,742 (80.2%) voted for Germany and 12,800 (19.8%) for Denmark; invalid votes were not expelled. Only three small communities on Föhr had Danish majorities, but remained with Germany. Zone II remained closed to Germany.

Zone II consisted of the former districts:

- Tønder , southern part : 17,283 or 87.9% for Germany, 2,376 votes or 12.1% for Denmark;

- Flensburg , southern part : 6,688 votes or 82.6% for Germany, 1,405 votes or 17.4% for Denmark;

- Husum , northern part : 672 votes or 90.0% for Germany, 75 votes or 10.0% for Denmark

and the

- City of Flensburg : 27,081 votes or 75.2% for Germany, 8,944 votes or 24.8% for Denmark

Zone III

A third voting zone, which extended to a line between Husum-Schlei and Eider-Schlei ( Danewerklinie ), was proposed by the Danish National Liberals. Surprisingly, it was included in the first draft of the voting regulation, but after violent disputes within Denmark, at the instigation of the Danish government, it was removed from the final procedure.

Voting Committee

The referendum was carried out in 1920 under the supervision of the Inter-Allied Voting Commission for Schleswig ( French Commission Internationale de Surveillance du Plébiscite Slesvig (CIS) ). The CIS was active from 1919 and during this time also exercised provisional sovereignty over Schleswig. The commission consisted of the British Sir Charles Marling (President), the French Paul Claudel , the Norwegian Thomas Thomassen Heftye and the Swede Oscar von Sydow . An additional seat was available to the United States of America, but was not occupied. The British Charles Frederick Brudenell-Bruce acted as general secretary of the CIS . The German district administrator from the Tondern district, Emilio Böhme, was assigned as an adviser to the commission alongside the Danish-minded editor Hans Peter Hanssen .

Assignment of North Schleswig

The cession of North Schleswig to Denmark took place on June 15, 1920. The day is known in Denmark as the Reunification Day Genforeningsdag and on June 15 celebrations about the reunification (Genforeningsfest) are still held in North Schleswig .

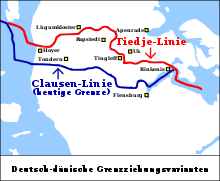

After 1920, the Clausen line divided the Duchy of Schleswig into a Danish North Schleswig and a German South Schleswig . North Schleswig with 3993 km² is smaller than South Schleswig with around 5300 km². The German government offered the Danish government to settle the disputed territorial claims bilaterally. Nevertheless, the Danish government insisted on the solution, unique in international law, of regulating this within the framework of the Versailles Peace Treaty , even though Denmark was not a belligerent state during the First World War . The area between the Clausen and Tiedje lines of 1376 km² is practically the "war gain" of non-warring Denmark.

Clausen and Tiedje lines

Schleswig is linguistically and culturally influenced by the Danish, German and Frisian sides, which led to conflicts at the time of nationalization in the 19th century. At the same time as the growing nationality conflict, there was a language change in parts of Schleswig, as a result of which native Danish and Frisian dialects were successively replaced by High and Low German. This was due to the influence of the Holstein nobility, the economic connections to the south and the establishment of German as the school and church language in southern Schleswig. The linguistic-cultural heterogeneity of Schleswig, which in some cases had an impact on families, made it difficult to divide Schleswig as one nation, as discussed during the German-Danish War.

In 1891 the Danish historian Hans Victor Clausen presented the Clausen Line, a possible German-Danish border line between Tønder and Flensburg, which later became the border between voting zones I and II in a modified version. The line also roughly corresponded to the border between the areas with German and Danish church language , which has been running since the Reformation , whereby it must be noted that Danish and North Frisian as colloquial languages extended further south until the language change in the 19th century, which today u. a. can still be read from the place names of Danish and Frisian origin. The language change began even before the national political confrontation between German and Danish and overlapped them in time. Varieties like Angel Danish disappeared by the beginning of the 20th century. The Clausen line also ran near the demarcation line during the Schleswig-Holstein uprising in 1849/1850 between Scandinavian troops on the one hand and Prussian troops on the other, north of Tondern and south of Flensburg.

As an alternative to the Clausen Line, the German civil servant and pastor Johannes Tiedje developed the Tiedje Line in 1920, which ran a few kilometers north of the Clausen Line. In addition, he compensated for the unequal distribution of the minorities: 25,329 Germans in Zone I (North Schleswig) to 12,800 Danes in Zone II (Central Schleswig). If the so-called Tiedje Belt had remained with Germany in 1920, the German minority in Denmark would have been smaller, the Danish minority in Germany larger and both minorities would have been roughly the same.

Of the approximately 400,000 inhabitants of Schleswig in the middle of the 19th century, around 200,000 were Danish-oriented. Between the German-Danish War and 1900, around 60,000 Danish Schleswig-Holstein residents emigrated. A census from 1900 showed the distribution of mother tongues in Schleswig at that time: in the three northern districts of Hadersleben, Aabenraa and Sønderburg there were 80% Danish populations, and in these districts there were almost 100,000 of the 140,000 Danes in Schleswig (70% of Schleswig's Danes), in the district of Tondern with around 25,500 Danes the Danish population was 45% (18% of Schleswig's Danes), in the urban and rural districts of Flensburg around 6% (4% of Schleswig's Danes), in the southern districts of Schleswig and Husum and Eckernförde each less than 5% and a total of only 8% of the Danes in Schleswig.

The 1905 census showed 134,000 Danish native speakers in all of Schleswig-Holstein. About 98,400 of them are in the three northern districts of Hadersleben, Aabenraa and Sønderburg (73.4% of Danish native speakers in Schleswig-Holstein). In the Tondern district, around 25,100 people were Danish native speakers (18.7% of Danish native speakers in Schleswig-Holstein). In the city and district of Flensburg, in the districts of Schleswig, Husum and Eckernförde and in the rest of Schleswig-Holstein, there were a total of 10,500 Danish native speakers (7.8% of all Danish native speakers in Schleswig-Holstein).

The census of December 1, 1910 showed 123,828 Danish native speakers (74.4%) out of a total population of 166,348 in Northern Schleswig, later voting zone I.

| District / mother tongue 1910 | Residents | German | German % | Danish | Danish % | Other | Other % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aabenraa district | 32,416 | 8,157 | 25.2 | 23,918 | 73.8 | 341 | 1.0 |

| Part ceded by the Flensburg district | 2,449 | 1,223 | 50.0 | 1,196 | 48.8 | 30th | 1.2 |

| Hadersleben district | 63,575 | 12,451 | 19.6 | 50,610 | 79.6 | 514 | 0.8 |

| District of Sonderburg | 39.909 | 10,776 | 27.0 | 28,562 | 71.6 | 571 | 1.4 |

| Part of the district of Tondern | 27,999 | 8,297 | 29.6 | 19,542 | 69.8 | 160 | 0.6 |

| North Schleswig as a whole | 166,348 | 40,954 | 24.6 | 123,828 | 74.4 | 1,566 | 1.0 |

The 1910 census showed that 8,786 Danish native speakers (8.2%) out of a total population of 107,068 lived in voting zone II. The proportion of German native speakers was 97,416 (91.0%).

The results of the 1900 and 1910 censuses were largely reflected in the 1920 vote. Since the two voting zones were largely congruent with the five northern districts and the urban district of Flensburg (a small part of the Husum district was added, part of the Schleswig district was not part), over 90% of Schleswig's Danes lived in the voting area. Even in Zone I and II, together with 47% for Germany (77,071 votes) and 53% for Denmark (88,231 votes), Denmark was slightly overweight.

Looking at the districts, the following picture emerged: The three northern districts had Danish votes between 68% and 84%. In the district of Flensburg, 59.4% of the 1,350 voters in the northern part voted for Denmark, but a total of 76.6% of the 9,443 voters for Germany, in the district of Tondern, 59.1% of the 17,306 voters in the northern part for Denmark, but in total 65.9% of the 36,965 eligible voters for Germany. There were individual areas within Zone I north of the border, which were rated en bloc, with German votes of over 75%. Ignoring the results in these border areas, clearly German-speaking areas of the two cross-border districts of Tondern and Flensburg, was - in addition to displeasure with the electoral mode itself - cause for criticism from the German side. The criticism led to Tiedjes' proposal to separate the clearly German-dominated areas of the districts and other adjacent areas, in which the conditions were balanced, from the northern zone and to add to the southern zone.

Minorities

After the German-Danish War in 1864, a Danish minority emerged in Schleswig. With the partition in 1920, minorities from the other side were found on both sides of the new border. There is also the North Frisian ethnic group on the North Sea between Eider and Wiedau (Vidå). Both the German and Danish minorities maintain several associations, libraries, schools and kindergartens to promote their own culture. Both minorities are so-called minorities of opinion (religious minorities).

consequences

After 1920, around 12,000 Germans emigrated from North Schleswig. Some of the emigration took place as a result of expulsions. From the city of Tondern alone, around 30% of the population (1,700 inhabitants) emigrated to the German Reich after the referendum . After the emigration, between 30,000 and 40,000 members of the German minority lived in North Schleswig. The population share in 1930 was about 20%.

Based on the significantly reduced number of pupils in German schools after World War II, it can be concluded that around 2/3 of the German minority assimilated into the Danish population in Northern Schleswig after 1945. There were also other expulsions. Today the proportion of the German minority in the total population in North Schleswig is 6-8%.

In the district of Südtondern , the population grew by 27.8% between 1919 and 1925 as a result of the influx from Northern Schleswig. This made the district of Südtondern one of the fastest growing districts in the German Empire .

Voting posters

In the run-up to the Schleswig referendums, both national parties campaigned for their own point of view. A number of voting posters were created, appealing to the national sentiment of the voters.

Danish postcard from 1920 shows Mor Danmark and one of the Sønderjyske Piger (South Jutland girls)

Emergency note from Husbyholz (Zone II) with advertising for the German side

literature

- Klaus Alberts: Referendum in 1920. When Northern Schleswig came to Denmark. Boyens Buchverlag, Heide 2019, ISBN 978-3-8042-1514-6 .

- Jan Schlürmann : 1920. A limit for peace. The referendum between Germany and Denmark. Wachholtz, Kiel 2019, ISBN 978-3-529-05036-7 .

- Manfred Jessen-Klingenberg : The referendum of 1920 in historical review . In: Grenzfriedenshefte . No. 3 , 1990, ISSN 1867-1853 , pp. 210-217 .

- Hans Schultz Hansen: The Schleswig and the division. In: Borders in the history of Schleswig-Holstein and Denmark. (= Studies on the economic and social history of Schleswig-Holstein. Volume 42). 1st edition. Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster 2006, ISBN 3-529-02942-4 .

- Martin Rheinheimer : Boundaries and Identities in Transition. In: Borders in the history of Schleswig-Holstein and Denmark. (= Studies on the economic and social history of Schleswig-Holstein. Volume 42). 1st edition. Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster 2006, ISBN 3-529-02942-4 .

Web links

- German ethnic group in North Schleswig Associations, clubs and institutions of the German minority in Denmark

- Dansk Skoleforening for Sydslesvig e. V.

- Danish Optanten in Schleswig after the introduction of the Prussian conscription

- Broder Schwensen: From the German defeat to the division of Schleswig 1918–1920. Flensburg 1995, ISBN 3-925856-25-0 .

Footnotes

- ^ Prime Minister Niels Neergaard's speech on reunification in Düppel / Dybbøl 1920, Danmarkshistorien.dk

- ↑ The borders 800–1100. Frontier portal

- ↑ An unknown piece of national history. In: Schleswig-Holsteinische Landeszeitung. No. 268, November 14, 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ What happened in 1864 ( Memento of May 10, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Dybbøl Banke History Center

- ^ Troels Fink: Germany as a problem of Denmark - the historical prerequisites of Danish foreign policy . Christian Wolff, Flensburg 1968, p. 70 f.

- ↑ Dieter Gosewinkel: Naturalization and exclude. The nationalization of citizenship from the German Confederation to the Federal Republic of Germany (= critical studies on historical science . Volume 150). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-525-35165-8 , p. 208.

- ↑ All figures taken from: Karl Alnor: The results of the referendums of February 10 and March 14, 1920 in the 1st and 2nd Schleswig zone (= Heimatschriften des Schleswig-Holsteiner-Bund . Volume 15 ). Verlag des Schleswig-Holsteiner-Bund, Flensburg (Lutherhaus) 1925, DNB 578738325 .

- ^ Danmark (history) . In: Johannes Brøndum-Nielsen, Palle Raunkjær (ed.): Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon . 2nd Edition. tape 26 : Supplement: A – Øyslebø . JH Schultz Forlag, Copenhagen 1930, p. 255 (Danish, runeberg.org ).

- ↑ Afstemningszoner. ( Memento of March 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Grænseforeningen

- ↑ Danevirkebevægelsen. ( Memento from May 19, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Grænseforeningen

- ↑ web.archive.org

- ^ Institute for Schleswig-Holstein Contemporary and Regional History: The national contrast. (= Sources on the history of the German-Danish border region. Volume 4). Institute for Regional Research and Information in the German Border Association, 2001, pp. 176, 183.

- ^ Sarah Wambaugh: Plebiscites since the world war: with a collection of official documents. Volume 2, Carnegie endowment for international peace, 1933, p. 44. (English)

- ^ Willi Walter Puls: North Schleswig: the separated part of the North Mark. J. Klinkhardt, 1937, p. 60. ( limited preview on Google Book Search ).

- ^ Karl Strupp : Dictionary of international law and diplomacy, 3 vol., 1924–1929, p. 118

- ↑ https://www.statistikebibliothek.de/mir/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/SHMonografie_derivate_00000004/1226-20.pdf

- ↑ Grænser i Sønderjylland. Grænseforeningen, accessed February 25, 2015 .

- ^ Karl N. Bock: Middle Low German and today's Low German in the former Danish Duchy of Schleswig. Studies on the lighting of language change in fishing and Mittelschleswig . In: Det Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab (ed.): Historisk-Filologiske Meddelelser . Copenhagen 1948.

- ^ Manfred Hinrichsen: The development of language conditions in the Schleswig region . Wachholtz, Neumünster 1984, ISBN 3-529-04356-7 .

- ↑ Jacob Munkholm Jensen: Dengang jeg drog af sted: Danske immigranter i the Amerikanske Borgerkrig . Copenhagen / København 2012, ISBN 978-87-7114-540-3 .

- ^ Census of December 1, 1900 - results of the districts , Statistics of the German Empire, Volume 150

- ↑ Census of December 1, 1900 - Danish minority , Statistics of the German Empire, Volume 150

- ↑ wiki-de.genealogy.net

- ↑ https://www.destatis.de/GPStatistik/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/DEMonografie_derivate_00001664/WiSta-Sonderheft-02.pdf;jsessionid=FC90FA4B81C946E1696E1C094A9578BB

- ↑ https://www.destatis.de/GPStatistik/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/DEMonografie_derivate_00001664/WiSta-Sonderheft-02.pdf;jsessionid=FC90FA4B81C946E1696E1C094A9578BB

- ^ Result of the referendum , German Historical Museum

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Figures in part from Population-Ploetz: Space and Population in World History, Volume 4: Population and Space in Modern and Modern Times. Ploetz, Würzburg 1965.

- ^ Tammo Luther, Franz Steiner Verlag, Volkstumsppolitik des Deutschen Reiches 1933-1938: The Germans Abroad in the Field of Tension between Traditionalists and National Socialists

- ↑ https://www.destatis.de/GPStatistik/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/DEMonografie_derivate_00001664/WiSta-Sonderheft-02.pdf;jsessionid=FC90FA4B81C946E1696E1C094A9578BB