Cat worm infections

Worm infections in cats - the infection ( infection ) of cats (Felidae) with parasitic worms - are common. Most worm species occur in both domestic and other cats worldwide, but there are regional, species and lifestyle differences with regard to the frequency of infestation. After classifying the corresponding parasites in the zoological system, the infections can be divided into those caused by roundworms and flatworms - in the latter especially tapeworms and flukes - other strains are of no veterinary importance. While roundworms usually do not need an intermediate host for their reproduction, the development cycle of flatworms always takes place via intermediate hosts.

As predators, cats are the ultimate host for most worms. The worms colonize various internal organs as so-called endoparasites ("internal parasites"), but usually cause little or no disease. The infection does not necessarily have to manifest itself in a worm disease (helminthosis) . For most parasites, infection can be detected by examining the feces for eggs or larvae. Some worms found in cats can also spread to humans and are thus zoonotic pathogens. The cat round worm and the fox tapeworm are of greater importance . Such worm infections in particular should be combated by regularly deworming cats that are in close contact with humans.

Roundworm infections

Various representatives of the roundworms ( Nematoda ) parasitize cats , especially roundworms, hookworms, lungworms, hairworms and stomach worms. Coccidia co-infections are particularly common in kittens.

Roundworm infestation

- → Main article: Roundworm infestation in cats

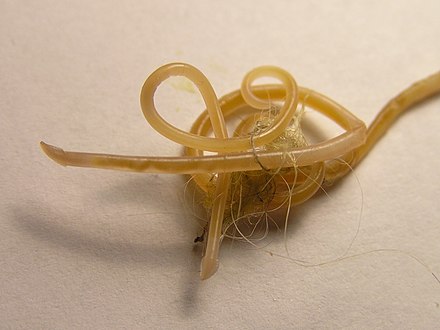

The most common roundworm in most cats is Toxocara mystax (Syn. Toxocara cati ), the infestation with Toxascaris leonina is less common . Only in ocelots in Texas was T. leonina detectable in every animal and thus the most common parasite; in bobcat in Nebraska it was observed almost as often as T. mystax . Both types of roundworms occur worldwide and the roundworm infestation is a very common endoparasitosis. The up to 10 cm long adult roundworms live in the small intestine . The female worms produce a large number of eggs, which get into the environment with the faeces. The infectious larvae develop in the eggs after about four weeks.

The infection always occurs orally and can take place in three ways:

- via the uptake of larvae infected transport hosts,

- from the mother cat to her puppies via breast milk (only with T. mystax ) or

- as a dirt infection through ingestion of eggs containing larvae.

In principle, roundworms do not need intermediate hosts. However, infection via transport hosts such as rodents is the most common route of infection in adult cats. The larvae migrate in the transport host through the intestinal wall into the muscles or internal organs. In the cat, they are released during digestion. In the event of a dirt infection , the cat ingests eggs that contain larvae. The larvae are released in the stomach, pierce the wall of the stomach or small intestine and enter the lungs via the bloodstream. From here they are coughed up and by swallowing the sputum they get back into the small intestine, where they shed their skin on the adult worms . In T. mystax , the larvae can - as in the transport hosts - also migrate via the bloodstream to other organs (including the mammary gland ) and there assume a dormant stage in encapsulated nodules . The hormonally triggered mobilization of these dormant larvae in the mammary gland at the end of pregnancy is the basis of the third path of infection, which is the most common in kittens. The larvae excreted in the milk reach the kitten's intestines and then behave as they would when infected via transport hosts.

In general, roundworm infestation in cats remains asymptomatic. Only when the infestation is more severe do unspecific symptoms such as mushy faeces and, as a result of a lack of nutrients, shaggy fur, hair loss, emaciation and dehydration occur - especially in young animals . A massive infestation in young animals can lead to growth disorders of the skeleton with deformation of the bones and distended joints. Very rarely, there is an obstruction of the intestine due to the accumulation of worms or peritonitis due to worms piercing the intestinal wall. In these cases, severe general disorders (" acute stomach ") occur.

The diagnosis of worms in vomit can be made without special examinations. Roundworm infestation can be detected relatively reliably by microscopic detection of the eggs released from the feces using the flotation process.

Hookworm infestation

Hookworms are common in cats, especially Ancylostoma tubaeforme . Other hookworms such as Ancylostoma caninum (main host: dogs) and Uncinaria stenocephala (main host: foxes) are observed much less frequently in cats. Hookworms are up to 1.5 cm long and are parasites of the small intestine. The larvae of these hookworms are either ingested by transport hosts (rodents) or burrow through the cat's skin ( percutaneous infection).

Hookworm infection in cats often remains asymptomatic. With more severe infestation, they can cause emaciation, anemia or diarrhea. As with roundworms, the infection is detected by detecting the eggs in the feces using a flotation method. They are oval, smaller than roundworm eggs (about 60 × 40 µm in size) and the inside of them can already be seen to be furrowed when they are laid .

Stomach worms (ollulanosis)

Stomach worms (especially Ollulanus tricuspis ) are up to one centimeter long and colonize the gastric mucous membrane , where they lodge in its mucous layer or in the openings of the gastric glands. The entire development of O. tricuspis takes place in the stomach of the cat, the larvae given off by the females develop into the adult worms within the same animal. Other animals become infected by eating vomit from infected cats.

O. tricuspis rarely causes clinical symptoms in domestic cats. A stronger infestation shows up in occasional vomiting. Other cats, on the other hand, can show more severe clinical pictures with reluctance to eat, emaciation and dehydration. The infection can be detected by detecting the worms in gastric lavage samples or vomit. Since O. tricuspis is viviparous (larviparous), no worm eggs and only in exceptional cases larvae are detectable in the faeces.

Lungworm infestation (aelurostrongylosis)

The lungworm Aelurostrongylus abstrusus is up to one centimeter long and colonizes the lungs , more precisely the small bronchi and alveoli . In contrast to the nematode treated previously, lungworms need an intermediate host for their development . The female worms lay eggs from which larva L1 hatches while still in the airways. This is coughed up, swallowed and, after passing through the gastrointestinal tract, reaches the outside world via the feces. Here the larvae are infectious in a moist environment for up to six months. They invade various snails , which serve as intermediate hosts, and develop in them via larva L2 to larva L3. In most cases, however, cats do not become infected by eating snails, but rather via transport hosts such as amphibians, reptiles, birds and rodents who have previously ingested these snails. After ingestion, the larva bores its way through the cat's stomach or intestinal wall and enters the lungs via the bloodstream. The prepatency period - the period from infection to excretion of the first larvae - is around six weeks.

Lungworm infestation rarely causes symptoms in cats, it is considered to be self-healing. Only in the case of massive infestation or disorders of the immune system can respiratory problems such as coughing, difficult breathing, sneezing, eye and nasal discharge as well as unwillingness to eat, emaciation and listlessness occur. Sudden deaths very rarely occur when a particularly large number of larvae hatch in the airways. Lungworm infestation is established via the detection of up to 400 µm long larvae in the faeces using the larval emigration method , whereby it should be noted that they are excreted irregularly in the faeces. Detection in lung lavage samples or lung biopsies is more meaningful .

Hairworm infestation

Hairworms ( Capillaria ssp.) Are very thin, 0.7 to 8 cm long roundworms.

Hairworms are most common as parasites in the gastrointestinal tract of cats, for example Capillaria putorii . They are not considered to cause disease, but occasionally cause vomiting and diarrhea and, rarely, stomach ulcers with anemia. The eggs of gastrointestinal hairworms are oval, about 60–70 × 35–40 µm in size and can be detected using flotation methods.

The lung hairworm ( Capillaria aerophila ) is widespread in wild animals such as hedgehogs and foxes, but very rare in cats. The 25 to 35 mm long worm colonizes the airways. As with roundworms and lungworms, the eggs are coughed up, swallowed and excreted in the faeces. Earthworms serve as intermediate hosts, but the parasite is mostly transmitted to cats via intermediate transport hosts. The lung hairworm rarely causes symptoms; bronchitis with coughing only occurs when the infection is more severe - usually as a result of accompanying bacterial infections . Evidence can be provided by examining feces for eggs or examining lung lavage samples .

The urinary bladder hairworms ( Capillaria plica and Capillaria feliscati ) colonize the urinary bladder . The eggs are excreted in the urine, so infection can only be detected from the urine sediment . Urinary bladder hairworms can cause cystitis with urinary discharge disorders and, if more severe, anemia.

The liver hairworm ( Capillaria hepatica ) parasitizes the liver and can cause fatigue, vomiting, increased thirst and urination as well as jaundice . The infestation can only be established on the basis of a liver biopsy with a subsequent fine tissue examination of the tissue sample.

Trichinella infestation (Trichinellosis)

Infestation with trichinae (especially Trichinella spiralis ) is very rare in cats in Central Europe. Trichinae occur worldwide and have no development phase in the outside world. Infection occurs through ingestion of meat containing larvae. The larvae drill into the wall of the small intestine and develop into adult worms there. The larvae given off by the females reach the skeletal muscles via lymph or blood, where, as a waiting stage, they represent the source of infection for other carnivorous and omnivorous animals.

A small amount of trichinae remains in the cat without any symptoms. In the case of pronounced infestation - as in humans (→ trichinella ) - general disturbances, vomiting and bloody diarrhea can initially occur in the intestinal colonization phase. However, cats rarely experience muscle weakness, gait disorders, breathing problems and fever due to muscle inflammation as a result of the larvae that have migrated into the muscles.

Heartworm infestation (dirofilariasis)

Infection with the up to 30 cm long heartworm ( Dirofilaria immitis ) is rare in cats, the main host for this parasite is the dog. Dirofilariasis is of no importance in Central Europe, as the parasite is only native to the Mediterranean region and the US southern states. The disease is transmitted by stinging insects, which act as obligatory intermediate hosts. During the act of sucking, they ingest so-called microfilariae from the blood of infected animals. The development of larvae L3 takes place in the insects, which is transferred to a new host animal during another sucking act. The larvae L4 develop in the subcutaneous tissue. This migrates via the blood vessels into the auricles and the large vessels close to the heart and sheds its skin into the adult heartworm. The prepatency period is 8 months.

The heartworm has a relatively high disease-causing effect on cats. The disease manifests itself in poor general health, diarrhea and cough. It can be diagnosed by detecting the 250 µm microfilariae in the blood smear , which is difficult and therefore relatively unreliable in cats.

Kidney worm infestation

The infection with the kidney worm Dioctophyma renale is only found in southern Europe, Asia and North America and is also rare there in cats, the main host being mink . With a length of up to one meter, the kidney worm is the largest living parasitic nematode and shows a twofold host change: the first intermediate host is little bristle , the second freshwater fish. In the definitive host, it parasitizes mainly in the renal pelvis or fat. A kidney is usually affected without any symptoms. If both kidneys are affected, kidney dysfunction due to hydronephrosis or pyelonephritis can occur. The infection can be detected by a kidney biopsy or imaging tests. The barrel-shaped, yellow-brown and 71–84 × 45–52 µm² eggs only occur in the urine sediment when a female and male kidney worm meet in a kidney.

Tapeworm infections

In the case of tapeworm infections, a distinction must be made between infestation with adult tapeworms and infestation with their stages of development. The former plays a far greater role in cats; the most common triggers are the thick-necked and cucumber seed tapeworm. The harmful effect of the adult tapeworms is low, only with stronger infestation can loss of appetite, emaciation and shaggy fur occur due to the deprivation of nutrients. The limbs wandering out of the anus can cause itching and thus the so-called "sledding" (sliding on the rear part).

Infestation with the thick-necked tapeworm

The 15 to 60 cm long and about 5 mm wide Dickhalsige tapeworm ( Hydatigera or Taenia taeniaeformis , even cats tapeworm called) parasitizes in the small intestine. It is a common tapeworm in cats, it only occurs in exceptional cases in other predators. The released tapeworm limbs leave the anus with the feces or through active migration. The wired oncospheres (mature eggs with larva L1, "six-hook larva") are released from the dried-on limbs in a moist environment . These can be spread by flies, beetles and snails. The wired oncospheres are absorbed by (obligatory) intermediate hosts (rodents, squirrels) and the released six-hook larvae colonize the intermediate host's liver in particular. From it the already tapeworm-like, up to 30 cm long fin ( Strobilocercus fasciolaris ) arises , which is picked up when the intermediate host eats. Once in the small intestine, the scolex everts itself and the tapeworm sucks onto the intestinal mucosa. The prepatency averages five weeks.

In most cases, only two to ten cat tapeworms are found in the same animal; they excrete around four to five limbs every day. These elongated trapezoidal structures may already be visible to the naked eye in the anal region. The wired oncospheres, which are around 35 µm in size, can be detected in the feces using flotation methods. In one study, an infection rate of 25.9% was determined in autopsies, of which only 10% was detected in the flotation process and 27% after centrifugation. In addition, the eggs cannot be distinguished morphologically from those of other representatives of the Taeniidae (including the fox tapeworm).

Infestation with the cucumber seed tapeworm

The cucumber core tapeworm ( Dipylidium caninum ) - named after its limbs reminiscent of a cucumber core - is up to 80 cm long and parasitizes in the anterior small intestine. The cat flea , occasionally also the cat hairling , acts as an obligatory intermediate host . The tapeworm limbs released in the intestine leave the anus with the feces or through active migration. The eggs are ingested by the insect larvae, penetrate their intestinal wall and develop in the fat body to the fin stage (cysticercoid). Depending on the outside temperature, the cysticerkoid is infectious as soon as the adult flea hatches or only a few days later. The infection occurs by eating the fleas, whereupon the fin in the small intestine grows into an adult tapeworm. The prepatency period is about three weeks.

The cucumber seed tapeworm infestation can be determined by detecting the limbs in the anal region or detecting the 35–53 µm eggs or egg packets in the feces using a flotation method. However, these detection methods are very uncertain. In one study, an infestation rate of 34.5% could be determined in autopsies, although all previous faecal examinations were negative.

Infestation with the fox tapeworm

The infestation with the fox tapeworm ( Echinococcus multilocularis ) is very rare in domestic cats (0.4%), they represent a secondary host - foxes act as the main host. Since the infection with this parasite is life-threatening for humans (see below ), the low frequency of infestation is also of importance for health policy.

The fox tapeworm, which is only around three millimeters long, is found all over the northern hemisphere. It parasitizes in the small intestine, mostly in the back third, and plants itself deep between the intestinal villi. Every two weeks a wired oncosphere- containing tapeworm limb is released and excreted in the feces. The wired oncospheres are very stable in the environment, freeze themselves and most disinfectants survive unscathed. They are only sensitive to drought, temperatures above 80 ° C and sodium hypochlorite . They are ingested by intermediate hosts (especially rodents) and develop within 40 to 60 days into a large, spongy tissue ( metacestode ) with the infectious protoscolices . The cat is infected by ingestion from the intermediate hosts. The prepatency period is one to four months.

The infestation usually causes no symptoms in cats. It can be detected by means of the movable, approximately one millimeter long limbs in the feces or the anal region as well as oncospheres already released in the intestine using flotation methods. The latter cannot be distinguished morphologically from those of the other Taeniidae . Due to the cyclical release, a one-time examination of the faeces is only about 30% safe. Further diagnostic options are a specific ELISA for faecal samples and DNA detection using PCR . According to the WHO guidelines for combating this parasite, all equipment and materials used in diagnostics must be autoclaved or incinerated.

Rarely occurring tapeworms

Infections with Taeniidae other than the thick-necked tapeworm are rare in cats. The 30 to 150 cm long Taenia pisiformis (main hosts: dogs, foxes) needs rabbits and rodents as intermediate hosts. Cats are not very suitable final hosts for this tapeworm, it is mostly excreted by the cat before the formation of egg-containing (gravid) limbs. Infestation with the 50 to 250 cm long Taenia hydatigena (main hosts: dogs and foxes), whose intermediate hosts are pigs, ruminants and horses, and with Taenia crassiceps (intermediate hosts, rabbits and rodents) is also rare. These representatives do not cause any symptoms in cats. Their medical significance lies in the fact that their eggs are morphologically indistinguishable from those of the fox tapeworm, and that Taenia hydatigena is a zoonotic pathogen, albeit less often.

For the fish tapeworm ( Diphyllobothrium latum ) too , cats are not very suitable final hosts. It grows up to 1.5 m long and 2 cm wide in cats. The fish tapeworm needs two intermediate hosts: In the first ( copepods ) the procercoid forms, the plerocercoid, which is infectious for mammals, in the body cavity and the muscles of fish. Spirometra erinacei-europaei , another representative of the Diphyllobothriidae, is very rare in Central Europe and occurs mainly in the Mediterranean region. Copepods also act as the first intermediate host, and frogs, snakes and birds as the second.

In addition to the cucumber tapeworm, other members of the Dipylidiidae family can occur in cats . However, these are mainly found in the Mediterranean area, only Joyeuxiella pasqualei has meanwhile also been observed in Germany. Its intermediate hosts are dung beetles (Aphodiidae), but transport hosts such as reptiles and small mammals can also be involved in the chain of infection. It is up to 50 cm long. Joyeuxiella echinorhynchoides is only about half as long, its chain of infection corresponds to that of J. pasquallei . Diplopylidium noelleri and Diplopylidium acanthotretum are about 12 cm long and need dung beetles or fleas as intermediate hosts.

Infestation with members of the genus Mesocestoides is very rare in cats, although it is native to Central Europe. Their first intermediate host is probably moss mites, while reptiles, birds and mammals serve as the second, depending on the species.

Infestation with fin stages

Finn stages are very rare in cats. They damage the animal through their space-consuming growth with the destruction of infected organs.

The rice- grain-like fin stage ( tetrathyridium ) of Mesocestoides leptothylacus can rarely occur in cats. The actual second intermediate host are field mice . Severe infestation can lead to severe clinical pictures with severe decrease ( cachexia ) and deaths due to peritonitis . The coenurus of Taenia serialis and the cysticercus of Taenia crassiceps caused central nervous disorders (similar to the coenurosis of sheep ) as a result of damage to the brain .

Further fin stages occurring in cats are the metacestode of the tripartite dog tapeworm ( Echinococcus granulosus ), the sparganum of Spirometra mansonoides and the cysticercus of the pork tapeworm ( Taenia solium ). In most cases, however, they do not cause any symptoms of the disease, but are instead discovered as secondary findings during autopsies.

Infections caused by flukes

Infections by flukes ( Trematoda ) are rare in Central Europe and generally have no symptoms. They can be determined by detecting the eggs in the feces.

Liver fluke infestation

The liver fluke found in cats ( Opisthorchis felineus , Pseudoamphistomum truncatum and Metorchis bilis ) require a two-fold host change for their development. Water snails serve as the first intermediate host and freshwater fish as the second. Cats become infected by ingesting fish. The encapsulated (encysted) metacercariae in fish are very resilient and can only be safely killed by cooking. In rare cases, liver fluke infestation can cause intestinal inflammation with diarrhea, a disturbed general condition and changes in the liver and pancreas.

Intestinal gel infestation

Different intestinal fluke occur in cats, which, like the liver fluke, develop via two intermediate hosts. The first intermediate host is always a freshwater snail. The second intermediate host - and thus the source of infection for cats - varies depending on the type of parasite: in Alaria alata it is tadpoles , reptiles, birds and mammals, in Metagonimus yokogawai and Apophallus donicus fish, in Isthmiophora melis fish and amphibians and in Echinochasmus perforans tadpoles and fish . An infestation of intestinal leeches rarely causes symptoms such as diarrhea.

Lung gel infestation

Lung fluids (in Asia especially Paragonimus westermani , in America especially P. kellicotti ) do not play a role in Europe. The first intermediate host are water snails, the second freshwater crabs and crabs. Infection occurs through ingestion of raw shellfish. Lung leeches were found quite frequently in tigers and leopards in Thailand , but not in bengal cats . In America, they are found in both domestic cats and wildlife. The metacercariae that are released in the intestine migrate to the lungs, where they develop in cysts into adult leeches. As with other lungworms, the eggs are coughed up and released into the environment through the faeces.

The infestation with lung fluke can remain asymptomatic, but it can also trigger breathing problems similar to those of cat asthma . When the cysts burst, a pneumothorax with acute shortness of breath can develop. The infection can be detected by examining the faeces for eggs, by means of lung lavage samples or by means of an x-ray of the lungs.

Frequency of infestation and its influencing factors

The frequency of infestation varies greatly depending on the type of worm. In a German study on 3,167 domestic cats, endoparasites were detected in 24% of the animals using the flotation method, whereby T. mystax had the highest infestation rate with 26%. Another study on 441 faecal samples found T. mystax in only 3.9% of the samples, but here too this roundworm was the most common parasite. Infestation with T. mystax also dominates in Belgium, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia and Nigeria, where the infestation rates are up to 60%. In Qatar , on the other hand, tapeworms ( T. taeniaeformis: 76%, Dipylidiidae: 43%) were observed in stray cats , T. mystax only in 0.4% of the animals.

There are numerous factors influencing worm infestation. Wild animals are usually affected much more frequently than cats in human care, as the latter are often dewormed on a regular basis. In domestic cats, too, there are clear differences between purely indoor cats and those with free access or stray cats, as rodents or fish are more often ingested by the latter, which are a source of infection as intermediate or transport hosts. In addition, feral domestic and wild cats occasionally eat vomit from other cats when they are hungry, so that stomach worms are much more common in them. Almost 90% of stray cats in Spain were infected with gastrointestinal worms. Cats in larger herds such as animal shelters or laboratory facilities are affected significantly more often due to the closer contact with potential worm carriers. In examinations of large cats and other wild cats, depending on the species, worm eggs or larvae were found in 66 to 100% of the animals.

In addition to globally occurring parasites such as T. mystax , some have a limited range. This can be due to geographical or climatic conditions and the presence of suitable intermediate hosts. For example, the cat's liver fluke ( Opisthorchis felineus ) is more common in Asia as well as southern and eastern Europe, in Germany especially in eastern Brandenburg, where an infection rate of 16% was determined. The fish tapeworm occurs in Germany mainly along the large rivers and in the coastal regions, in Switzerland on the large lakes. Most Dipylidiidae can only be found in southern Europe.

Diagnosis

| material | parasite |

|---|---|

| Feces ( flotation ) | Roundworms, hooks, gastrointestinal hairworms, adult tapeworms, liver, lung and intestinal leeches |

| Feces ( emigration ) | Lungworms |

| Stomach contents | Stomach worms |

| Tissue samples | Trichinae (muscle) Liver hairworm (liver) Kidney worm (kidney) |

| blood | Heartworm |

| urine | Urinary bladder hairworms kidney worm |

There is hardly any reliable data on the actual infestation rates in the total populations of the various cat species. Only a few worm infections can be clinically proven - for example, when roundworms occur in the vomit or tapeworm limbs in the anal region.

For most cat species there are no or at most individual studies on regionally limited populations. Most studies are based on excrement tests in domestic cats. However, a number of worm infections cannot be detected with this examination method or the detection is only uncertain due to cyclical excretion such as with fox and cucumber tapeworm. If necessary, microscopic methods have to be supplemented by complex molecular biological processes, for example to distinguish eggs of the Taeniidae from one another.

The few surveys based on autopsies are not based on random samples , but on material sent in from deceased animals. Above all, for infestation with the fin stages of tapeworms, the autopsy is the only reliable detection method - apart from a few complex imaging procedures .

Combat

Complete elimination of worm infections in cats is impossible. The development cycles of the parasites cannot be interrupted, as new generations of parasites always grow back through free-living cats or other hosts. The fight against possible intermediate hosts is hardly practicable and ecologically unjustifiable. The harmless removal of cat excrement is a hygienic measure that at least leads to a dilution of the pathogen.

The treatment of worm infections is mostly limited to cats kept in human care. Most infections are rather harmless for cats, as a pathogen-host balance is established when the immune system is intact. However, since some of them can cause health disorders and some also represent a potential danger to humans, regular worming treatments for cats in the human environment make perfect sense. The European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) - the European association of experts on parasites in domestic animals - has therefore issued recommendations for combating worm infections. These are adapted to regional characteristics by national veterinary specialist societies. Such guidelines also exist in the United States and are published here by the Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC).

The recommendations, which were last adapted in January 2008 according to the ESCCAP guidelines for Germany, aim to protect cats “... against infections with worms and their consequences through professional diagnostics, therapy and prevention” . Targeted control is recommended for roundworms, hookworms and fox tapeworms in particular. Heartworm control only plays a role in Central Europe for cats (and dogs) that are to be brought to or come from the Mediterranean region.

If the mother is infected with Toxocara, kittens should be treated with a suitable anthelmintic ( anthelmintic ) from the age of three weeks and then every two weeks up to two weeks after weaning. The mother cat should also be treated after the birth, as dormant Toxocara larvae are activated during this time. A safe prophylaxis against T. mystax is only offered once a month, but this should only be considered for cats in larger positions or with contact with small children. Quarterly prophylactic deworming is generally suggested. For the treatment of roundworms, drugs based on emodepside , fenbendazole , flubendazole , mebendazole , milbemycin oxime , moxidectin , pyrantel and selamectin are approved for domestic cats in Germany . These medicinal substances are broad-spectrum anthelmintics and also have an effect against most of the other roundworms found in cats, which in individual cases may also be absent or insufficient. Of these substances, only moxidectin, milbemycin oxime and selamectin are effective in protecting against heartworms. Stomach worms are not covered by any of these agents, here in Germany are not approved for cats products on the market, so that other veterinary medicinal products on the basis of levamisole or ivermectin rededicated to be. In the case of kidney worms, only the affected kidney can be removed.

For the control of the fox tapeworm, which is native to all of Central and Eastern Europe - for the spread of which cats are of little importance - it is recommended not to feed raw meat or slaughterhouse waste. Regular excrement tests or monthly prophylactic treatment against tapeworms are indicated for outdoor cats or cats that hunt rodents. It is important that every occurrence of morphologically identical tapeworm eggs ( Taeniidae ) must be diagnosed in a special laboratory. In the case of positive evidence, rigid hygiene measures such as bathing in protective clothing and strict, harmless removal of the faeces must be carried out. For the treatment and prophylaxis of the fox tapeworm, praziquantel or epsiprantel are used, praziquantel is also effective against the other flatworms. Some European countries such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, Malta, Finland, Sweden or Norway require prophylactic treatment against fox tapeworm as an entry requirement as documented in the EU pet passport.

Dangers to humans

Some of the worms that occur in cats can be transmitted to humans, i.e. zoonotic pathogens .

The fox tapeworm ( Echinococcus multilocularis ) poses the greatest threat to humans . It causes the clinical picture of alveolar echinococcosis , which is characterized by small-bubble destruction of internal organs -> 99.9% of which affects the liver - and which, if left untreated, usually ends fatally. However, this disease is very rare, and since cats are rarely found, cats play no role in the spread of this parasite, in the opinion of most authors. However, in an Austrian study of 21 patients, the possession of cats turned out to be a risk factor for the disease.

Toxocara mystax can be transmitted from roundworms to humans as a smear infection. The most common source of infection in small children is sandpits contaminated with cat excrement. The infection corresponds to that of a transport host and is - in contrast to infection with the dog roundworm - mostly clinically inconspicuous. The larvae can also migrate into the internal organs or muscles of humans (so-called larva migrans visceralis ). Occasionally, such migrating larvae can cause eye damage, central nervous symptoms (headache, behavioral disorders), enlarged liver, bronchitis with cough or, in children, allergic reactions such as hives . The nematode worms such as A. caninum , C. hepatica and kidney worms, which are rather rare in cats , can also attack internal organs of humans as migrating larvae. Cats do not play a role in the spread of trichinella , as trichinae are rare in them and cats are usually not eaten by humans.

The cucumber seed tapeworm can rarely cause illnesses in children if they - mostly accidentally - swallow infected fleas (→ dipylidiasis ). Here, like cats, humans act as ultimate hosts; direct infection from a cat is not possible. In addition, the house dog plays a far greater role in the spread of this tapeworm. The other representatives of the Dipylidiidae are also zoonotic pathogens.

The cat liver fluke can be transferred to humans in rare cases. The infection does not occur through cats, but through ingestion of metacercarial-containing fish. In addition to cats, otters and foxes play a role as final hosts in maintaining the parasite population. Intestinal leeches are also pathogenic for humans, but cats hardly play a role in the spread of these parasites; in Alaria alata , the infection mostly occurs via pork (pigs act as transport hosts). The same applies to the spread of lung fluids such as Paragonimus westermani - humans become infected by ingesting raw shellfish.

To protect against zoonotic worm infections, the ESCCAP recommends:

- Hygiene measures such as hand washing or gardening with gloves,

- no consumption of unwashed plants (vegetables, fruits and mushrooms),

- regular parasitological examinations or prophylactic deworming of the cats,

- Regular removal of cat excrement (this is not practical for outdoor cats and cats living in the wild) and

- Avoid environments that are potentially contaminated with worm stages (dog meadows, gardens or playgrounds, sandboxes), especially for children.

literature

- Johannes Eckert: textbook of parasitology for veterinary medicine . 2nd Edition. Enke-Verlag, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8304-1072-0 .

- Theodor Hiepe, Regine Ribbeck: Textbook of Parasitology . tape 4 . Fischer-Verlag, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-437-20252-9 .

- Regine Ribbek, Steffen Rehbein: Diseases of the cat . Ed .: Marian C. Horzinek. 4th edition. Enke-Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8304-1049-2 , "Helminthosen", p. 207-226 .

- Thomas Schnieder (Ed.): Veterinary Parasitology . 6th edition. Parey-Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-8304-4135-9 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ ESCCAP: Control of intestinal protozoa in dogs and cats. In: Kleintierpraxis 58 (2013), pp. 416–430.

- ^ DB Pence et al .: Helminths of the ocelot from southern Texas. In: J Wildl Dis. 39 (2003), pp. 683-689. PMID 14567231

- ↑ KL Tiekotter: helminth species diversity and biology in the bobcat, Lynx rufus (Schreber), from Nebraska. In: J Parasitol. 71: 227-234 (1985). PMID 3998960

- ↑ AM Hargis et al .: Ollulanus tricuspis found by fecal flotation in a cat with diarrhea. In: J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 182 (1983): pp. 1122-1123.

- ↑ Binke Dürr: Fine-needle aspiration of the lungs in two cats with aelurostrongylus abstrusus infection. In: Kleintierpraxis 54 (2009), pp. 88–92.

- ↑ DK Curtsinger et al .: Gastritis Caused by Aonchotheca putorii in a domestic cat. In: J Am Vet Med Assoc. 203: 1153-1154 (1993). PMID 8244862

- ↑ a b c d e Frank Dieffenbacher: Investigation of the parasite fauna of feral domestic cats and their treatment with selamectin and praziquantel. Vet. Med. Diss., FU Berlin, 2007. ( online version )

- ↑ Heinz Sager: Lungworms, Capillaria aerophila . In: Katzen Magazin 1/2007 ( online version )

- ^ Giant Kidney Worm Infection in Mink and Dogs. merckvetmanual.com ( Memento of the original from March 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b C. Adolph et al .: Prevalence of Dipylidium caninum and Taenia taeniaeformis in cats. In: AAVP Abstracts 2011

- ↑ P. Deplazes et al .: Echinococcus multilocularis coproantigen detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in fox, dog, and cat populations. In: J Parasitol. 85: 115-121 (1999). PMID 10207375

- ↑ a b J. Eckert et al .: WHO / OIE Manual on Echinococcosis in Humans and Animals: a Public Health Problem of Global Concern . World Organization for Animal Health and World Health Organization, 2001. ISBN 92-9044-522-X ( pdf )

- ↑ A. Wunschmann et al .: Cerebral cysticercosis by Taenia crassiceps in a domestic cat . In: Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 15 (2003), pp. 484-488.

- ^ A b S. Patton and AR Rabinowitz: Parasites of wild felidae in Thailand: a coprological survey. In: J Wildl Dis. 30: 472-475 (1994). PMID 7933301

- ^ A b Eleanor C. Hawkins: Pulmonary parasites . In: Richard W. Nelson and C. Guillermo Couto: Small Animal Internal Medicine . Mosby, 3rd ed., Pp. 302-303. ISBN 0-323-01724-X

- ^ A b S. Patton et al .: A coprological survey of parasites of wild neotropical felidae. In: J Parasitol. 72: 517-520 (1986). PMID 3783346

- ↑ D. Barutzki and R. Schaper: Endoparasites in dogs and cats in Germany 1999-2002. In: Parasitol Res. 90 (2003), Suppl 3, S148-S150. PMID 12928886

- ↑ C. Epe et al .: Results of parasitological examinations of faeces on horses, ruminants, pigs, dogs, cats, hedgehogs and rabbits in the years 1998–2002. In: Dtsch. Veterinarian Weekly 111 (2004), pp. 243-247. PMID 15287577

- ↑ a b O. Vanparijs et al .: Helminth and protozoan parasites in dogs and cats in Belgium. In: Vet Parasitol. 38, pp. 67-73 (1991). PMID 2024431

- ^ PA Overgaauw: Prevalence of intestinal nematodes of dogs and cats in The Netherlands. In: Vet Q. 19 (1997), pp. 14-17. PMID 9225423

- ^ S. Nichol et al .: Prevalence of intestinal parasites in domestic cats from the London area. Vet Rec. 109: 252-253 (1981). PMID 7340062

- ↑ a b W.M. Guterbock and ND Levine: Coccidia and intestinal nematodes of East Central Illinois cats. In: J Am Vet Med Assoc. 170, pp. 1411-1413 (1977). PMID 873847

- ^ CV Spain et al .: Prevalence of enteric zoonotic agents in cats less than 1 year old in central New York State. In: J Vet Intern Med. 15 (2001), pp. 33-38. PMID 11215908

- ↑ CS Palmer et al .: National study of the gastrointestinal parasites of dogs and cats in Australia. In: Vet Parasitol. 151 (2008), pp. 181-190. PMID 18055119

- ↑ N. Umeche and AE Ima: Intestinal helminthic infections of cats in Calabar, Nigeria. In: Folia Parasitol (Prague) 35 (1988), pp. 165-168. PMID 3169644

- ↑ a b M.A. Abu-Madi et al .: Descriptive epidemiology of intestinal helminth parasites from stray cat populations in Qatar. In: J Helminthol. 82 (2008), pp. 59-68. PMID 18199386

- ^ A b C. Calvete et al .: Gastrointestinal helminth parasites in stray cats from the mid-Ebro Valley, Spain. In: Vet Parasitol. 28 (1998), pp. 235-240. PMID 9637225

- ↑ G. Miró et al .: Prevalence of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii and intestinal parasites in stray, farm and household cats in Spain. In: Vet Parasitol. 126 (2004), pp. 249-255. PMID 15567588

- ^ R. Schuster et al .: Investigations on the endoparasite fauna of the house cat in East Brandenburg. In: Berl Münch Tierarztl Wochenschr 110 (1997), pp. 48-50

- ↑ a b c d ESCCAP recommendations for combating worms (helminths) in dogs and cats. German adaptation of the ESCCAP recommendation. ( pdf )

- ↑ Vetidata list of wormer products approved for dogs and cats in Germany ( pdf ( Memento from November 21, 2008 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ P. Deplazes: Ecology and epidemiology of Echinococcus multilocularis in Europe. In: Parassitologia. 48 (2006), pp. 37-39. PMID 16881392

- ↑ P. Kreidl et al .: Domestic pets as risk factors for alveolar hydatid disease in Austria. In: Am J Epidemiol. 147 (1998), pp. 978-981. PMID 9596476

- ^ Paul C. Beaver: Larva migrans . In: Experimental Parasitology 5 (1956), pp. 587-621.