Talk:Richard Garriott and Boeing 777: Difference between pages

|2={{WikiProject Texas| class=B|importance=Low|nested=}} |

Arpingstone (talk | contribs) Sorry ,but smoke in the cabin is not notable enough for an encyclopedia |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<!-- This article is a part of [[Wikipedia:WikiProject Aircraft]]. Please see [[Wikipedia:WikiProject Aircraft/page content]] for recommended layout. --> |

|||

{{talkheader}} |

|||

{{Infobox Aircraft |

|||

{{Blp}} |

|||

|subtemplate={{Infobox Boeing Aircraft}} |

|||

{{WikiProjectBanners |

|||

|name =Boeing 777 |

|||

|1={{WPBiography|living=yes|class=B|priority=}} |

|||

|image =Image:united.b777-200.n772ua.arp.jpg <!-- Flight images are preferred for aircraft - Please do not change this image without a talk page discussion --> |

|||

|2={{WikiProject Texas| class=B|importance=Low|nested=}} |

|||

|caption =Boeing 777-200 of [[United Airlines]], the launch customer of the 777 |

|||

|3={{WikiProject Video games|class=B|importance=High}} |

|||

|type =[[Wide-body aircraft|Wide-body]] [[jet airliner]] |

|||

|4={{UTTalk}} |

|||

|national origin = [[United States]] |

|||

|5={{WikiProject Astronautics| class=B|importance=Low|nested=}} |

|||

|manufacturer =[[Boeing Commercial Airplanes]] |

|||

|designer = <!--only appropriate for single designers, not project leaders--> |

|||

|first flight =[[June 12]] [[1994]] |

|||

|introduction =[[June 7]] [[1995]] with [[United Airlines]] |

|||

|retired = |

|||

|status = Active |

|||

|primary user = [[Singapore Airlines]] <!--Top 4 users listed per http://www.planespotters.net/Production_List/Boeing/777/statistics.html as of 1 Sept. 2008.--> |

|||

|more users = [[Emirates Airline]] <br/> [[United Airlines]] <br/> [[Air France]]<br/> <!-- Limit is three in more users field. Please separate with <br/>.--> |

|||

|produced =1993 - present |

|||

|number built = 736 as of August 2008<ref name="777_O_D"/> |

|||

|unit cost = US$200-254 million (2007)<ref name="prices">[http://www.boeing.com/commercial/prices/ Boeing Commercial Airplanes prices], The Boeing Company. Retrieved: 10 September 2007.</ref> |

|||

|variants with their own articles = |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Boeing 777''' is a long-range, [[Wide-body aircraft|wide-body]] twin-engine [[airliner]] built by [[Boeing Commercial Airplanes]]. The world's largest [[twinjet]] and commonly referred to as the "Triple Seven", it can carry between 283 and 368 passengers in a three-class configuration and has a range from 5,235 to 9,450 [[nautical miles]] (9,695 to 17,500 km). Distinguishing features of the 777 include the six wheels on each main landing gear,<ref name=boeingjets>Norris, Guy and Wagner, Mark. ''Boeing Jetliners.'' Zenith Imprint, 1996, p. 89. ISBN 0760300348</ref> its circular [[fuselage]] cross section,<ref>Norris and Wagner (1996), p. 92</ref> the largest diameter [[turbofan]] engines of any aircraft, the pronounced "neck" {{huh?}} aft of the flight deck, and the blade-like end to the tail cone.<ref name=boeingjets/> |

|||

As of August 2008, 56 customers have placed orders for 1,092 777s.<ref name="777_O_D">[http://active.boeing.com/commercial/orders/displaystandardreport.cfm?cboCurrentModel=777&optReportType=AllModels&cboAllModel=777&ViewReportF=View+Report 777 Model Orders and Deliveries summary], Boeing. July 2008. Retrieved [[14 August]] [[2008]].</ref> Direct market competitors to the 777 are the [[Airbus A330|Airbus A330-300]], [[Airbus A340|A340]], and [[Airbus A350|A350 XWB]], which is currently under development. The 777 may eventually be replaced by a new product family, the [[Boeing Y3]], which would draw upon technologies from the [[Boeing 787|787]]. |

|||

== Dead Links == |

|||

The link to the article about the kids that stole the alcohol and left behind the camera at Garriott's estate is now a dead link. "^ Claire Osborn (2007-04-05). Nine who left pics at crime scene identified. Retrieved on 2007-05-01." -- [[User:Rappo|Rappo]] 22:48, 19 August 2007 (UTC) |

|||

:It's trivia in any event. See [[WP:TRIVIA]].[[Special:Contributions/139.48.25.61|139.48.25.61]] ([[User talk:139.48.25.61|talk]]) 20:49, 9 April 2008 (UTC) |

|||

==Development== |

|||

== Proof of influence == |

|||

===Background=== |

|||

In the 1970s, Boeing unveiled new models: the twin-engine [[Boeing 757|757]] to replace the venerable [[Boeing 727|727]], the twin-engine [[Boeing 767|767]] to challenge the [[Airbus A300]], and a [[trijet]] 777 concept to compete with the [[McDonnell Douglas DC-10]] and the [[Lockheed L-1011 TriStar]].<ref>{{cite news | title = The 1980s Generation | publisher = [[Time (magazine)|Time]] | date = [[August 14]], [[1978]] | url = http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,946981,00.html | accessdate = 2008-07-19}}</ref> Based on a re-winged 767 design, the proposed 275-seat 777 was to be offered in two variants: a 2,700 nautical miles (5,000 km) transcontinental and an 4,320 nmi (8,000 km) intercontinental. |

|||

The article repeatedly makes references to Garriott and Origin's influence in the gaming industry, but fails to provide proof of said influence. Surely there must be articles or figures that can be referenced? |

|||

The twinjets were a big success, due in part to the 1980s [[ETOPS/LROPS|ETOPS]] regulations. However the trijet 777 was cancelled (much like the trijet concept of the Boeing 757) in part because of the complexities of a trijet design and the absence of a 40,000 lbf (178 kN) engine. The cancellation left Boeing with a huge size and range gap in its product line between the 767-300ER and the 747-400. The DC-10 and L-1011, which entered service in early 1970s, were also due for replacement. In the meantime, Airbus developed the [[Airbus A340|A340]] to fulfill that requirement and to compete with Boeing. |

|||

--[[User:Nibble|Nibble]] 18:44, 11 August 2005 (UTC) |

|||

===Design phase=== |

|||

:The way he designed the graphical presentation of the game worlds in his ''Ultima'' games was very influential. Many games that followed from other developers emulated his presentation. But, no, I don't have a reference for this fact. I'm sure it's out there somewhere. You're right, it should be added to the article. [[User:Frecklefoot|<nowiki></nowiki>]]— [[User:Frecklefoot|Frecklefoot]] | [[User talk:Frecklefoot|Talk]] 14:11, August 12, 2005 (UTC) |

|||

In the mid-1980s Boeing produced proposals for an enlarged 767, dubbed 767X. There were also a number of in-house designations for proposals, of which the 763-246 was one internal designation that was mentioned in public.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://webarsiv.hurriyet.com.tr/2000/01/02/168791.asp|title=Hurriyet.com - Kokpit|language=Turkish|last=Cebeci|first=Uğur}}</ref> The 767X had a longer fuselage and larger wings than the existing 767, and seated about 340 passengers with a maximum range of 7,300 nautical miles (13,500 kilometers). The airlines were unimpressed with the 767X: they wanted short to intercontinental range capability, a bigger cabin cross section, a fully flexible cabin configuration and an operating cost lower than any 767 stretch. By 1988 Boeing realized that the only answer was a new design, the 777 [[twinjet]].<ref>Norris and Wagner (1996), p. 9-14</ref> |

|||

== Owner of property on the moon? == |

|||

[[Image:Boeing 777 Cockpit.jpg|thumb|right|[[Glass cockpit]] of United Airlines 777]] |

|||

I've heard it was something the Russians left behind and auctioned off, not Nasa. Don't have a source though. [[User:FrozenPurpleCube|FrozenPurpleCube]] 22:49, 14 September 2005 (UTC) |

|||

Designing of the 777 was different from previous Boeing jetliners. For the first time, eight major airlines ([[Cathay Pacific]], [[American Airlines|American]], [[Delta Air Lines|Delta]], [[All Nippon Airways|ANA]], [[British Airways|BA]], [[Japan Airlines|JAL]], [[Qantas]], and [[United Airlines|United]]) had a role in the development of the plane as part of a "Working Together" collaborative model employed for the 777 project.<ref name="airl_777">{{cite book| last = Birtles | first = Philip | authorlink = | coauthors = | title = Boeing 777, Jetliner for New Century | publisher = MBI Publishing| date = 1998 | location = | id = ISBN 0-7603-0581-1 }}</ref> |

|||

It was either Lunokhod 1/Luna 17 or Lunokhod 2 / Luna 21 - there are sources on the web that mention one or the other, so I'm not sure which is correct. Somebody please ask him! |

|||

At the first "Working Together" meeting in January 1990, a 23-page questionnaire was distributed to the airlines, asking each what it wanted in the new design. By March 1990 a basic design for the 767X had been decided upon; a cabin cross-section close to the 747's, 325 passengers, [[fly-by-wire]] controls, [[glass cockpit]], flexible interior, and 10% better [[Available seat miles|seat-mile costs]] than the A330 and MD-11. ETOPS was also a priority for United Airlines.<ref>Norris and Wagner (1996), p.13</ref> |

|||

Lunokhod 1 / Luna 17 was sold for $68500 at a Sotheby's auction in New York in December 1993, but it's not clear (to me) whether Garriott was the buyer. Tweesdad 19:23, 4 July 2006 (UTC) |

|||

All software, whether produced internally to Boeing or externally, was to be written in [[Ada (programming language)|Ada]]. The bulk of the work was undertaken by Honeywell who developed an Airplane Information Management System (AIMS). This handles the flight and navigation displays, systems monitoring and data acquisition (e.g. flight data acquisition). |

|||

This [http://www.ehrensenf.de/node/790/ interview] gives the answers and a guided tour to his mansion.--[[User:Nemissimo|Nemissimo]] ([[User talk:Nemissimo|talk]]) 19:11, 6 December 2007 (UTC) |

|||

United's replacement program for its aging DC-10s became a focus for Boeing's designs. The new aircraft needed to be capable of flying three different routes; [[Chicago]] to [[Hawaii]], Chicago to [[Europe]] and non-stop from the [[hot and high]] [[Denver]] to Hawaii.<ref>Norris and Wagner (1996), p.14</ref> |

|||

== Harry Potter Online == |

|||

In October 1990, United Airlines became the launch customer when it placed an order for 34 [[Pratt & Whitney]]-powered 777s with options on a further 34.<ref>{{cite news | title = Business Notes AIRCRAFT | publisher = [[Time (magazine)|Time]] | date = [[October 29]], [[1990]] | url = http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,971474,00.html | accessdate = 2008-07-19}}</ref> Production of the first aircraft began in January 1993 at Boeing's [[Everett, Washington|Everett]] plant near [[Seattle]].<ref name="sabbagh180">''Sabbagh, p. 180''.</ref> In the same month, the 767X was officially renamed the 777, and a team of United 777 developers joined other airline teams and the Boeing team at the [[Boeing Everett Factory]].<ref>Norris and Wagner (1996), p.15</ref> Divided into 240 design teams of up to 40 members, working on individual components of the aircraft, almost 1,500 design issues were addressed.<ref>Norris and Wagner (1996), p.20</ref> |

|||

Seems unlikely that Origin had a contract for Harry Potter Online, doesn't it? I'm not terribly familiar with Harry Potter but someone who knows better is welcome to delete this comment. <small>—The preceding [[Wikipedia:Signatures|unsigned]] comment was added by [[User:24.183.35.115|24.183.35.115]] ([[User talk:24.183.35.115|talk]] • [[Special:Contributions/24.183.35.115|contribs]]){{#if:19:58, 28 April 2007| 19:58, 28 April 2007|}}.</small><!-- Template:Unsigned --> |

|||

The 777 was the first commercial aircraft to be designed entirely on [[computer]]. Everything was created on a 3D [[Computer-aided design|CAD]] [[software]] system known as [[CATIA]], sourced from [[Dassault Systemes]]. This allowed a virtual 777 to be assembled, in simulation, to check for interferences and to verify proper fit of the many thousands of parts before costly physical prototypes were manufactured.<ref name="bca_cad">"[http://www.boeing.com/commercial/777family/pf/pf_computing.html Computing & Design/Build Processes Help Develop the 777]." [[Boeing Commercial Airplanes]].</ref> Boeing was initially not convinced of the abilities of the program, and built a mock-up of the [[Boeing fuselage Section 41|nose section]] to test the results. It was so successful that all further mock-ups were cancelled.<ref>Norris and Wagner (1996), p.21</ref> |

|||

:I've added a reference. It seems they were working with a company called Liquid Development. --[[User:Mrwojo|Mrwojo]] 01:49, 29 April 2007 (UTC) |

|||

=== Into production === |

|||

== relevancy of his political donations in external links == |

|||

[[Image:United Airlines 777 N777UA.jpg|thumb|right|The first Boeing 777 in commercial service, [[United Airlines]]' N777UA]] |

|||

The 777 included substantial international content, to be exceeded only by the [[Boeing 787|787]]. International contributors included [[Mitsubishi Heavy Industries]] and [[Kawasaki Heavy Industries]] (fuselage panels), [[Fuji Heavy Industries, Ltd.]] (center wing section),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.boeing.com/companyoffices/aboutus/boejapan.html |title=Boeing Co. and Japan - 777 program partners |publisher= Boeing }}</ref> Hawker De Havilland ([[Elevator (aircraft)|elevators]]), ASTA ([[Flight control surfaces#Rudder|rudder]])<ref name="sabbagh112-114">Sabbagh, p. 112-114.</ref> and [[Ilyushin]] (jointly designed overhead baggage compartment).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.boeing.com/news/releases/1998/news_release_980609b.html |title=Boeing 777 Technical Research Center 777 joint design |date= [[9 June]] [[1998]] |publisher= Boeing }}</ref> |

|||

Why is this needed? How does it add to the article? I just don't see a reason for it. [[User:Nar Matteru|Nar Matteru]] ([[User talk:Nar Matteru|talk]]) 14:04, 6 February 2008 (UTC) |

|||

:Good point, I've removed it. If you run across frivolous links or links that violate [[WP:EL]] in other articles, please don't hesitate to remove them. ˉˉ<sup>[[User:Anetode|'''anetode''']]</sup>[[User_talk:Anetode|╦╩]] 19:21, 6 February 2008 (UTC) |

|||

On [[April 9]] [[1994]] the first 777, WA001, was rolled out in a series of fifteen ceremonies held during the day to accommodate the 100,000 invited guests.<ref name="sabbagh281-284">''Sabbagh, p. 281 - 284''.</ref> First flight took place on [[June 14]] [[1994]], piloted by 777 Chief Test Pilot John E. Cashman, marking the start of an eleven month flight test program more extensive than that seen on any previous Boeing model.<ref>{{cite web | title = Chronology Of The Boeing 777 Program | url = http://www.boeing.com/commercial/777family/pf/pf_milestones.html |publisher= Boeing | archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20070609173529/http://www.boeing.com/commercial/777family/pf/pf_milestones.html | archivedate=2007-06-09 | accessdate = 2008-07-19 }}</ref> |

|||

== spaceflight == |

|||

On [[May 15]] [[1995]] Boeing delivered the first 777, registered N777UA, to [[United Airlines]]. The [[Federal Aviation Administration|FAA]] awarded 180 minute [[ETOPS/LROPS|ETOPS]] clearance ("ETOPS-180") for PW4074 engined 777-200s on [[May 30]] [[1995]], making the 777 the first aircraft to carry an ETOPS-180 rating at its entry into service.<ref>180 minutes ETOPS approval was granted to the [[General Electric GE90]] powered 777 on [[October 3]] [[1996]], and to the [[Rolls-Royce Trent 800]] powered 777 on [[October 10]] [[1996]].</ref> The 777's first commercial flight took place on [[June 7]] [[1995]] from London's [[Heathrow Airport]] to [[Washington Dulles International Airport]]. The development, testing, and delivery of the 777 was the subject of the documentary series, "21st century Jet: The Building of the 777". |

|||

according to the article, he is scheduled to go to the ISS by the flight [[Soyuz TMA-13]] and to come back by the flight [[Soyuz TMA-12]]...6 month before. Can someone find the correct dates about this flight? (sorry for my english, I'm [[frog|french]]) --[[Special:Contributions/82.227.142.250|82.227.142.250]] ([[User talk:82.227.142.250|talk]]) 22:44, 12 April 2008 (UTC) |

|||

In 1996 [[Japan Air System]] held an airplane livery design contest for its 777.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.boeing.com/companyoffices/aboutus/boejapan.html |title=The Boeing Company and Japan |publisher= Boeing |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20070705115614/http://www.boeing.com/companyoffices/aboutus/boejapan.html |archivedate=2007-07-05}}</ref><ref name="RainbowDesignMain">"{{cite web |url=http://www.jas.co.jp/new777/e/g.htm |title=JAS B777 Rainbow Design Competition |publisher= Japan Air System|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20010618235100/www.jas.co.jp/new777/e/g.htm |archivedate=2001-06-18}}]</ref> The winning design was featured on the JAS 777 for the airline's 25th anniversary in April 1997.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.jas.co.jp/new777/e/indexe.htm |title=Rainbow Design Competition/Presenting the result |publisher= Japan Air System |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/19990117061858/www.jas.co.jp/new777/e/indexe.htm |archivedate=1999-01-17}}</ref> |

|||

== Spaceflight == |

|||

[[Image:ba b777-200 g-viid planform arp.jpg|thumb|right|[[Planform]] view of a [[British Airways]] Boeing 777-200 on takeoff.]] |

|||

Is he going to do the first civilian spacewalk??[[User:Danielshy|Danielshy]] ([[User talk:Danielshy|talk]]) 15:22, 13 April 2008 (UTC) <small>—Preceding [[Wikipedia:Signatures|unsigned]] comment added by [[User:Danielshy|Danielshy]] ([[User talk:Danielshy|talk]] • [[Special:Contributions/Danielshy|contribs]]) 15:20, 13 April 2008 (UTC)</small><!-- Template:Unsigned --> <!--Autosigned by SineBot--> |

|||

Due to rising fuel costs, airlines began looking at the Boeing 777 as a fuel-efficient alternative compared to other widebody jets.<ref name=fuelsaver>{{cite web|url=http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,23853824-23349,00.html|title=Boeing under pressure as demand rises for fuel-saver 777 |date=[[June 13]], [[2008]]|publisher= The Australian Business|last=Thomas|first=Geoffrey|accessdate=2008-06-20}}</ref> With modern engines, having extremely low failure rates (as seen in the ETOPS certification of most twinjets) and increased power output, four engines are no longer necessary except for very large aircraft such as the [[Airbus A380]] or [[Boeing 747]]. |

|||

== Article focus == |

|||

[[Singapore Airlines]] is the largest operator of the Boeing 777 family with 76 in service as of 2008.<ref>[http://www.planespotters.net/Airline/Singapore-Airlines Singapore Airlines fleet listing], Plane-spotters.net. Retrieved [[15 August]], [[2008]].</ref> [[Emirates Airline]] is second with 60 777s as of 2008.<ref>[http://www.plane-spotters.net/Airline/Emirates?show=all Emirates Airline fleet listing], Plane-spotters.net. Retrieved [[15 August]], [[2008]].</ref> |

|||

How exactly did the article on Richard Garriot come to show his space flight as more important than his contributions to game design? He invented a genre. <span style="font-size: smaller;" class="autosigned">—Preceding [[Wikipedia:Signatures|unsigned]] comment added by [[Special:Contributions/129.21.143.62|129.21.143.62]] ([[User talk:129.21.143.62|talk]]) 19:06, 5 October 2008 (UTC)</span><!-- Template:UnsignedIP --> <!--Autosigned by SineBot--> |

|||

==Design== |

|||

Boeing employed advanced technologies in the 777. These features included: |

|||

* The largest and most powerful turbofan engines on a commercial airliner with a 128 inch (3.25 m) fan diameter on the [[General Electric GE90|GE90-115B1]]. |

|||

[[image:aa.b777-200er.n788an.mains.arp.jpg|thumb|right|Main [[undercarriage]] of an [[American Airlines]] 777-200ER on landing approach]] |

|||

* [[Honeywell]] [[Liquid crystal display|LCD]] [[glass cockpit]] flight displays |

|||

* Fully digital [[fly-by-wire]] flight controls with emergency manual reversion |

|||

* Fully software-configurable [[avionics]] |

|||

* [[Electronic flight bag]] |

|||

* Lighter design including use of [[composites]] (12% by weight)<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.boeing.com/commercial/787family/programfacts.html |title=Boeing 787 Program Fact Sheet|accessdate=2008-07-19}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Raked wingtips]] |

|||

* [[Fiber optic]] avionics network |

|||

* The largest [[undercarriage|landing gear]] and the largest tires ever used in a commercial jetliner. Each main gear tire of a 777-300ER carries a maximum rated load of 64,583 lb (29,294 kg) when the aircraft is fully loaded, the heaviest load per tire of any production aircraft ever built. |

|||

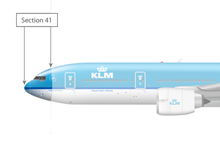

[[Image:KLM777-Sec41.png|thumb|left|[[Boeing fuselage Section 41|Section 41]] on a Boeing 777, the only major part shared with the 767]] |

|||

The 777 has the same [[Boeing fuselage Section 41|Section 41]] as the [[Boeing 767|767]]. This refers to the part of the aircraft from the tip of the nose, going to just behind the cockpit windows. From a head-on view, the end of the section is very evident. This is where the bulk of the aircraft's avionics are stored. |

|||

Boeing made use of work done on the cancelled [[Boeing 7J7]], which had validated many of the chosen technologies. A notable design feature is Boeing's decision to retain conventional [[Yoke (aircraft)|control yokes]] rather than fit [[Aircraft flight control systems#Digital|sidestick]] controllers as used in many fly-by-wire fighter aircraft and in some Airbus transports. Boeing viewed the traditional [[Aircraft flight control systems|yoke and rudder]] controls as being more intuitive for pilots. |

|||

Folding wingtips were offered when the 777 was launched, this feature was meant to appeal to airlines who might use the aircraft in gates made to accommodate smaller aircraft, but no airline has purchased this option.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.faa.gov/ATS/asc/publications/TACTICAL/LGATac.pdf|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20040924063450/http://www.faa.gov/ATS/asc/publications/TACTICAL/LGATac.pdf|archivedate=2004-09-24|title=FAA publication|format=PDF}}</ref><ref>[https://www.caa.govt.nz/aircraft/Type_Acceptance_Reps/Boeing_777.pdf Type Acceptance Report - Boeing 777]</ref> |

|||

===Interiors=== |

|||

[[Image:EVA Air's 777 Economy Class.jpg|thumb|right|Economy class interior of [[EVA Air]] 777-300ER in 3-3-3 layout]] |

|||

The interior of the Boeing 777, also known as the Boeing Signature Interior, has since been used on other aircraft, including the [[Boeing 767|767-400ER]], [[Boeing 747-400|747-400ER]], and newer [[Boeing 767|767-200s]] and [[Boeing 767|767-300s]]. The interior on the [[Boeing 737|Next Generation 737]] and the [[Boeing 757|Boeing 757-300]] also borrows elements from the 777 interior, introducing larger, more rounded overhead bins than the [[Boeing 737 Classic|737 Classics]] and 757-200, and curved ceiling panels. The 777 also features larger, more rounded, windows than most other aircraft. The 777-style windows were later adopted on the [[Boeing 767|767-400ER]] and [[Boeing 747-8]]. The [[Boeing 787]] and [[Boeing 747-8]] will feature a new interior evolved from the 777-style interior and, in the case of the 787, will have even larger windows. |

|||

Some 777s also have crew rest areas in the crown area above the cabin. Separate crew rests can be included for the flight and cabin crew, with a two-person crew rest above the forward cabin between the first and second doors,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.fromthecockpit.com/Gallery/displayimage.php?album=3&pos=10|title=From the Cockpit—777 forward crew rest}}</ref> and a larger overhead crew rest further aft with multiple bunks. |

|||

==Variants== |

|||

[[Image:Boeing 777s at Everett Field 01.jpg|thumb|right|Boeing 777 models await final delivery]] |

|||

Boeing uses two characteristics to define their 777 models. The first is the fuselage size, which affects the number of passengers and amount of cargo that can be carried. The 777-200 and derivatives are the base size. A few years later, the aircraft was stretched into the 777-300. |

|||

The second characteristic is [[Range (aircraft)|range]]. Boeing defined these three segments: |

|||

* ''A market'': 3,900 to 5,200 nautical miles (7,223 to 9,630 km)<ref name="atb_777x">{{cite web |url=http://airtransportbiz.free.fr/Aircraft/777X-1.html |title="Boeing 777X |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20060103195219/http://airtransportbiz.free.fr/Aircraft/777X-1.html |archivedate=2006-01-03}}." Mengus, A. AirTransportBiz.com (archive.org page).</ref> |

|||

* ''B market'': 5,800 to 7,700 nautical miles (10,742 to 14,260 km)<ref name="atb_777x"/> |

|||

* ''C market'': 8,000 nautical miles (14,816 km) and greater<ref name="atb_777x"/> |

|||

These markets are also used to compare the 777 to its competitor, the [[Airbus]] [[Airbus A340|A340]]. |

|||

When referring to variants of the 777, Boeing and the airlines often collapse the model (777) and the capacity designator (200 or 300) into a smaller form, either 772 or 773. Subsequent to that they may or may not append the range identifier. So the base 777-200 may be referred to as a "772" or "772A", while a 777-300ER would be referred to as a "773ER", "773B" or "77W". Any of these notations may be found in aircraft manuals or airline timetables.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.airlinecodes.co.uk/arctypes.asp |title=IATA & ICAO Aircraft Type Codes on airlinecodes.co.uk}}</ref> |

|||

===Initial models=== |

|||

====777-200==== |

|||

[[Image:020802 02.jpg|thumb|right|[[Delta Air Lines|Delta]]'s 777-200 in [[livery]] commemorating the [[2002 Winter Olympics]]]] |

|||

The 777-200 (772A) was the initial A-market model. The first customer delivery was to [[United Airlines]] {{Airreg|N|777UA|agency}} in May 1995. It is available with a [[maximum take-off weight]] (MTOW) from 505,000 to 545,000 pounds (229 to 247 tonnes) and range capability between 3,780 and 5,235 nautical miles (7,000 to 9,695 km). |

|||

The -200 is currently powered by two 77,000 lbf (343 kN) [[Pratt & Whitney]] [[Pratt & Whitney PW4000|PW4077]] turbofans, 77,000 lbf (343 kN) [[GE Aircraft Engines|General Electric]] [[General Electric GE90|GE90-77Bs]], or 76,000 lbf (338 kN) [[Rolls-Royce plc|Rolls Royce]] [[Rolls-Royce Trent|Trent 877s]].<ref>[http://www.boeing.com/commercial/777family/pf/pf_200product.html 777-200/-200ER Technical Characteristics], Boeing.</ref> |

|||

The first 777-200 built was used by Boeing's non-destructive testing (NDT) campaign in 1994–1995, and provided valuable data for the -200ER and -300 programs (see below). This ''A market'' aircraft was sold to [[Cathay Pacific Airways]] and delivered in December 2000. |

|||

The direct equivalent from Airbus is the [[Airbus A330-300]]. A total of 88 -200s have been delivered to ten different customers,<ref name="777_O_D"/> and 86 -200s were in airline service as of August 2008.<ref name="FI08">"World Airliner Census", ''[[Flight International]]'', 19-25 August 2008.</ref><!-- Updates require a newer reference. --> |

|||

====777-200ER==== |

|||

[[Image:FGSPU.jpg|thumb|right|[[Air France]] 777-200ER touches down at Paris Charles de Gaulle airport]] |

|||

Originally known as the '''777-200IGW''' (for "increased gross weight"), the longer-range ''B market'' 777-200ER (772B) features additional fuel capacity, with increased MTOW range from 580,000 to 631,000 pounds (263 to 286 tonnes) and range capability between 6,000 and 7,700 nautical miles (11,000 to 14,260 km). ''ER'' stands for Extended Range. The first 777-200ER was delivered to [[British Airways]] in February 1997,<ref name="Boe_777_back">[http://www.boeing.com/commercial/777family/background.html The Boeing 777 Program Background], Boeing</ref> who also were the first carrier to launch, in 2001, a [[British Airways#Special cabin configuration|10 abreast economy configuration]] in this airframe, which had originally been designed for a maximum 9 abreast configuration. |

|||

The 777-200ER can be powered by any two of a number of engines: the 84,000 lbf (374 kN) [[Pratt & Whitney]] [[Pratt & Whitney PW4000|PW4084]] or [[Rolls-Royce plc|Rolls-Royce]] [[Rolls-Royce Trent|Trent 884]], the 85,000 lbf (378 kN) [[General Electric GE90|GE90-85B]], the 90,000 lbf (400 kN) [[Pratt & Whitney PW4000|PW4090]], [[General Electric GE90|GE90-90B1]], or [[Rolls-Royce Trent|Trent 890]], or the 92,000 lbf (409 kN) [[General Electric GE90|GE90-92B]] or [[Rolls-Royce Trent|Trent 892]]. In 1998 [[Air France]] took delivery of a 777-200ER powered by [[General Electric GE90|GE90-94B]] engines capable of 94,000 lbf (418 kN) thrust. The Rolls Royce Trent 800 is the leading engine for the 777 with a market share of 43%. The engine is used on the majority of 777-200s, ERs and 300s but is not offered for the 200LR and 300ER.<ref> {{cite web | title = Leading engine for the 777 | url = http://www.rolls-royce.com/civil_aerospace/products/airlines/trent800/default.jsp | accessdate = 2008-07-19 }}.</ref> |

|||

On March 1997, [[China Southern Airlines]] made history by flying the 1st Boeing 777 scheduled transpacific route, which was the flagship Guangzhou-Los Angeles route. On [[April 2]] [[1997]], a Boeing 777-200ER, tail registration {{airreg|9M|MRA}} (dubbed the "Super Ranger") of [[Malaysia Airlines]], broke the [[Great Circle]] ''Distance Without Landing'' record for an airliner by flying east (the long way) from [[Boeing Field]], [[Seattle, Washington|Seattle]], to [[Kuala Lumpur]], [[Malaysia]], a distance of 20,044 km (10,823 nmi), in 21 hours, 23 minutes, more than a scheduled range of the 777-200LR. The flight was non-revenue with no passengers on board. The -200ER is also recognized for another feat; the longest [[ETOPS]]-related emergency flight diversion (177 minutes under one engine power) was conducted on a [[United Airlines]]' Boeing 777-200ER carrying 255 passengers on [[March 17]] [[2003]] over the southern Pacific Ocean.<ref> {{cite web | title = ALPA 50th Annual Safety Awards | url = http://www.alpa.org/DesktopModules/ALPA_Documents/ALPA_DocumentsView.aspx?itemid=1049&ModuleId=1284&Tabid=256 | accessdate = 2008-06-07 }}</ref> |

|||

The direct equivalents to the 777-200ER from Airbus are the [[Airbus A340|Airbus A340-300]] and the proposed [[Airbus A350|A350-900]]. As of August 2008, 407 777-200ERs had been delivered with 32 unfilled orders.<ref name="777_O_D"/> As of August 2008, 397 Boeing 777-200ER aircraft were in airline service.<ref name="FI08"/><!-- Updates require a newer reference. --> |

|||

====777-300==== |

|||

[[Image:Emirates.b777-300.a6-emv.arp.jpg|thumb|right|An [[Emirates Airline|Emirates]] 777-300 landing at [[London Heathrow Airport]]]] |

|||

The stretched A market 777-300 (773A) is designed as a replacement for 747-100s and -200s. Compared to the older 747s, the stretched 777 has comparable passenger capacity and range, and also burns one third less fuel and has 40% lower maintenance costs. |

|||

It features a 33 ft 3 in (10.1 m) fuselage stretch over the baseline 777-200, allowing seating for up to 550 passengers in a single class high density configuration and is also 29,000 pounds (13 tonnes) heavier. The 777-300 has tailskid and ground maneuvering cameras mounted on the horizontal tail and underneath the forward fuselage to aid pilots during taxi due to the aircraft's length. |

|||

It was awarded type certification simultaneously from the U.S. [[Federal Aviation Administration|FAA]] and European [[Joint Aviation Authorities|JAA]] and was granted 180 min ETOPS approval on [[May 4]] [[1998]] and entered service with [[Cathay Pacific]] later in that month. |

|||

The typical operating range with 368 three-class passengers is 6,015 [[nautical miles]] (11,135 km). It is typically powered by two of the following engines: 90,000 lbf (400 kN) [[Pratt & Whitney PW4000|PW4090]] turbofans, 92,000 lbf (409 kN) [[Rolls-Royce Trent|Trent 892]] or [[General Electric GE90|General Electric GE90-92Bs]], or 98,000 lbf (436 kN) PW-4098s. |

|||

Since the introduction of the [[Boeing 777#777-300ER|-300ER]] in 2004, all operators have selected the ER version of the -300 model, in some cases replacing 747-400 aircraft. The 777-300ER, with 365 seats, is capacious enough to displace 747-400 configured with 416 seats, and burns 20% less fuel per trip than the latter. Operators try to maintain operating margins by retaining first-class and business-class seats and reducing economy seating on flights that previously were served by the 747; [[Japan Airlines]] is introducing semi-partitioned "suites" that offer each passenger 20% more space than current first class seating.<ref>JAL Is Upgrading Some Seats, Wall Street Journal, June 11, 2008, p.D2</ref> [[Air New Zealand]] will replace all of its 747-400s with the 777-300ER.<ref name=fuelsaver/> |

|||

This aircraft has no direct Airbus equivalent but the [[Airbus A340|A340-600]] is offered in competition. A total of 60 -300s have been delivered to eight different customers,<ref name="777_O_D"/> and all were in airline service as of August 2008.<ref name="FI08"/><!-- Updates require a newer reference. --> |

|||

===Longer range models=== |

|||

====777-200LR====<!-- This section is linked from [[KLM]] --> |

|||

[[Image:GE90 B777-200LR engine.jpg|thumb|right|A [[General Electric GE90|GE90]] engine mounted on a 777-200LR.]] |

|||

The 777-200LR (772C) ("LR" for "Longer Range") became the world's longest range commercial airliner when it entered service in 2006. Boeing named this plane the ''Worldliner'', highlighting its ability to connect almost any two airports in the world,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.boeing.com/commercial/news/2005/q2/nr_050610g.html|title=Boeing 777-200LR Worldliner Arrives at Paris Air Show|date=2005-06-10|publisher=Boeing|accessdate=2008-08-22}}</ref> although it is still subject to [[ETOPS]] restrictions. It is capable of flying 9,450 nautical miles (17,501.40 km, equivalent to 7/16 of the earth's circumference) in 18 hours. Developed alongside the 777-300ER, the 777-200LR achieves this with either 110,000 lbf (489 kN) thrust General Electric GE90-110B1 turbofans, or as an option, GE90-115B turbofans used on the -300ER. |

|||

[[Rolls-Royce plc|Rolls Royce]] originally offered the [[Rolls Royce Trent|Trent 8104]] engine with a thrust of 104,000 to 114,000 lbf (463 to 507 kN) that has been tested up to 117,000 lbf (520 kN). However, Boeing and Rolls Royce could not agree on risk sharing on the project so the engine was eventually not offered to customers. Instead GE agreed on risk-sharing for the development of long range derivatives of the Boeing 777. The agreement stipulated that only GE engines would be offered on the 777-200LR and 777-300ER.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.flightglobal.com/articles/1999/07/21/54116/777-operators-object-to-ge-as-sole-supplier.html|title=777 operators object to GE as sole supplier|date=1999-07-21|publisher=Flight International|accessdate=2008-06-06}}</ref> |

|||

The 777-200LR was initially proposed as a 777-100X.<ref>[http://www.boeing.com/news/releases/1995/news.release.950710-c.html "Boeing Looking Ahead to 21st century"], Boeing, [[July 10]], [[1995]].</ref> It would have been a shortened version of the 777-200, analogous to the [[Boeing 747SP]]. The shorter fuselage would allow more of the take-off weight to be dedicated to fuel tankage, increasing the range. Because the aircraft would have carried fewer passengers than the 777-200 while having similar operating costs, it would have had a higher cost per seat. With the advent of more powerful engines the 777-100X proposal was replaced by the 777X program, which evolved into the Longer Range 777-200LR. |

|||

[[Image:B777-200LR Paris Air Show 2005 display.jpg|thumb|left|The first 777-200LR Worldliner at the 2005 [[Paris Air Show]] - destined for [[Pakistan International Airlines]]]] |

|||

The -200LR features a significantly increased MTOW and three optional auxiliary fuel tanks manufactured by [[Marshall Aerospace]] in the rear cargo hold.<ref name=auxtanks>[http://www.boeing.com/commercial/777family/200LR/auxtanks_fuel.html 777-200LR Auxiliary Fuel Tanks] at [[Boeing]].com</ref> Other new features include raked wingtips, a new main landing gear and additional structural strengthening. The roll-out was on [[February 15]] [[2005]] and the first flight was at [[March 8]], [[2005]]. The second prototype made its first flight on [[May 24]], [[2005]]. The -200LR's entry into service was in January 2006. The only mass-produced aircraft with greater unrefueled range is the [[KC-10 Extender]] military [[Aerial refueling|tanker]]. |

|||

On [[November 10]] [[2005]], a 777-200LR set a record for the longest non-stop flight by passenger airliner by flying 11,664 nautical miles (13,422 statute miles, or 21,602 km) eastwards (the westerly great circle route is only 5,209 nautical miles) from [[Hong Kong]], [[China]], to [[London]], [[United Kingdom|UK]],<ref>{{cite book |title=Guinness World Records |page=p. 200 |year=2007 |publisher=[[HiT Entertainment]] |location=London; New York City |isbn=9780973551440}}</ref> taking 22 hours and 42 minutes. This was logged into the [[Guinness World Records]] and surpassed the 777-200LR's design range of 9,450 nmi with 301 passengers and baggage.<ref>[http://www.boeing.com/commercial/777family/news/2005/q4/nr_051110g.html "Boeing 777-200LR Sets New World Record for Distance"], Boeing, [[November 10]], [[2005]].</ref> |

|||

On [[February 2]] [[2006]], Boeing announced that the 777-200LR had been certified by both FAA and EASA to enter into passenger service with airlines.<ref>[http://www.boeing.com/commercial/777family/news/2006/q1/060202e_nr.html "Boeing 777-200LR Worldliner Certified to Carry Passengers Around the World"], Boeing, [[February 2]], [[2006]].</ref> The first Boeing 777-200LR was delivered to [[Pakistan International Airlines]] on [[February 26]] [[2006]] and the second on [[March 23]] [[2006]]. PIA has at least nine 777s in service and the company plans to replace all of its older jets with the series. |

|||

Other customers include [[Air India]] and [[Turkmenistan Airlines]]. In November 2005, [[Air Canada]] confirmed an order for the jets. Also that month [[Emirates Airline]] announced they bought ten -200LRs as part of a larger 777 order (42 in all). On [[September 12]] [[2006]], [[Qatar Airways]] announced firm orders for the Boeing 777-200LR along with Boeing 777-300ER.<ref> [http://www.thepeninsulaqatar.com/Display_news.asp?section=Local_News&month=September2006&file=Local_News200609123265.xml Qatar Airways confirms 777 orders].</ref> On [[October 10]] [[2006]], [[Delta Air Lines]] announced two firm orders of the aircraft to add to its long-haul routes and soon after announced three more orders.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://news.delta.com/article_display.cfm?article_id=10431 | title=Delta Air Lines First U.S. Carrier to Take Delivery of Boeing 777-200LR | accessdate=2008-07-19}}.</ref> [[Air New Zealand]] is looking at the possibility of using the 777-200LR variant to add to their -200ERs for a new [[Auckland]] to [[New York]] route, beginning an ultra-long range route. Later, Air New Zealand elected to focus on the Boeing 787 and 777-300ER for future plans instead.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.flightglobal.com/articles/2006/10/30/210267/air-new-zealands-rob-fyfe-completes-restructuring-and-plots.html|title=Air New Zealand’s Rob Fyfe completes restructuring and plots expansion|date=2006-10-30|publisher=Flight International|last=Sobie|first=Brendan|accessdate=2008-07-19}}</ref> |

|||

The closest Airbus equivalent is the [[Airbus A340|A340-500HGW]]. The proposed future [[Airbus A350|A350-900R]] model, aims to have a range up to 9,500 nautical miles or 17,600 km. As of August 2008, 20 777-200LR aircraft had been delivered with 25 unfilled orders.<ref name="777_O_D"/> A total of 19 -200LRs were in airline service as of August 2008.<ref name="FI08"/><!-- Updates require a newer reference. --> |

|||

====777-300ER==== <!-- This section is linked from [[KLM]] --> |

|||

[[Image:Singapore Airlines B773 9V-SWA takeoff.jpg|thumb|right|A 777-300ER of [[Singapore Airlines]], the world's largest operator of the 777]] |

|||

The 777-300ER is the Extended Range (ER) version of the 777-300 and contains many modifications, including the [[General Electric GE90|GE90-115B]] engines, which are the world's most powerful jet engine with 115,300 lbf (513 kN) thrust. Other features include [[raked wingtips]], a new main landing gear, extra fuel tanks (2,600 gallons), as well as strengthened fuselage, wings, [[empennage]], nose gear, engine struts and nacelles, and a higher MTOW, 775,000 lb versus 660,000 lb for the 777-300. The maximum range is 7,930 [[nautical miles]] (14,685 [[km]]). The 777-300ER program was launched by [[Air France]], though for political reasons, [[Japan Airlines]] was advertised as the launch customer. The first flight of the 777-300ER was [[February 24]] [[2003]]. Delivery of the first 777-300ER to [[Air France]] occurred on [[April 29]] [[2004]].<ref name="Boe_777_back"/> |

|||

The main reason for the 777-300ER's extra 1,935 nmi (3,550 km) range over the 777-300 is not merely the capacity for an extra 2,600 gallons of fuel (45,220 to 47,890 gal), but the increase in the maximum take-off weight (MTOW). |

|||

[[Image:Air Canada 777.jpg|thumb|left|An [[Air Canada]] 777-300ER with [[Thrust reversal|thrust reversers]] and [[Spoiler (aeronautics)|spoilers]] deployed after landing]] |

|||

The -300ER is slightly less fuel efficient than the regular -300 because it weighs slightly more and has engines that produce more thrust. Both the -300 and -300ER weigh approximately 360,000 lb empty and have the same passenger and payload capacity, but the ER has a higher MTOW and therefore can carry about 110,000 lb more fuel than the -300. This enables the -300ER to fly roughly 34% farther with the same passengers and cargo. Without the increase in fuel capacity due to larger fuel tanks, the -300ER's range would still be 25% greater at equal payload. In a maximum payload situation, the -300 would only be able to fill its fuel tanks about 60%, while the -300ER could be filled to full capacity. |

|||

Since the introduction of the -300ER, six years after the -300's first delivery, all orders for the -300 series have been the ER variant. The 777-300ER's direct Airbus equivalent is the [[Airbus A340|A340-600HGW]]; however, as noted above, this model is also displacing the 747-400 as fuel prices rise, airline passenger traffic drops and airlines look for every opportunity to save fuel and fill airplanes with higher-margin customers. |

|||

The 777-300ER has been test flown with only one working engine for as long as six hours and 29 minutes (389 minutes) over the [[Pacific Ocean]] as part of its [[ETOPS/LROPS|Extended-range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards (ETOPS)]] trials. 180 minutes of successful and reliable operation on one workable engine are required for the ETOPS 180-minute certification. |

|||

As of August 2008, 156 777-300ERs had been delivered with 223 unfilled orders.<ref name="777_O_D"/> Additional firm commitments are believed to have been signed, as some airlines intend to use the 777 as a stopgap while they await the arrival of the delayed [[Boeing 787]].<ref name=fuelsaver/> |

|||

====777 Freighter==== |

|||

[[Image:Boeing 777 Freighter test flight.jpg|thumb|right|The first 777 Freighter, destined for [[Air France]], on a test flight.]] |

|||

The 777 Freighter (777F) is an all-cargo version of the 777-200LR. The 777F is expected to enter service in late 2008.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://boeing.com/commercial/777family/news/2005/q2/nr_050524g.html|title=Boeing Launches New 777 Freighter}}</ref> It amalgamates features from the 777-200LR and the 777-300ER, using the -200LR's structural upgrades and 110,000 lbf (489 kN) GE90-110B1 engines, combined with the fuel tanks and undercarriage of the -300ER. |

|||

With a maximum payload of 103 [[ton]]s, the 777F's capacity will be similar to the 112 tons of the 747-400F, with a nearly identical payload density. As Boeing's forthcoming [[747-8]] will offer greater payload than the -400F, Boeing is targeting the 777F as a replacement for older 747F and [[McDonnell Douglas MD-11|MD-11F]] freighters. It was launched on [[May 23]] [[2005]]. |

|||

The 777F promises improved operating economics compared to existing 100+ ton payload freighters. With the same fuel capacity as the 777-300ER, the 777F will have a range of 4,895 nmi (9,065 km) at maximum payload, although greater range will be possible if less weight is carried. For example, parcel and other carriers which are more concerned with volume than weight will be able to make non-stop trans-Pacific flights. |

|||

Airbus currently has no comparable aircraft but is developing two models with similar specifications to the 777F. The [[Airbus A330#A330-200F|A330-200F]] will carry less payload but is a smaller and a cheaper alternative. With a capacity of around 90 tons the proposed [[Airbus A350|A350-900F]] will be a more capable competitor, although slightly smaller than the 777F. The MD-11F is another comparable aircraft but with less range than the 777F. When the 777F enters service in 2008, it is expected to be the longest-range freighter in the world. The 747-400ERF can carry more cargo and travel farther than the 777F, but the 747-8F replacing it will have less range than the 747-400ERF in the interest of more payload. |

|||

On [[November 7]] [[2006]], [[FedEx Express]] cancelled its order of ten [[Airbus A380|Airbus A380-800Fs]], citing the delays in delivery. FedEx Express said it would buy 15 777Fs instead, with an option to purchase 15 additional 777Fs.<ref name="sosd_20061107">[http://www.signonsandiego.com/news/business/20061107-1333-france-airbus.html "FedEx Express cancels order for 10 Airbus A380s, orders 15 Boeing 777s"]. Frost, L. ''[[The San Diego Union-Tribune]]''. [[November 7]], [[2006]].</ref> FedEx's CEO stated that "[t]he availability and delivery timing of this aircraft, coupled with its attractive payload range and economics, make this choice the best decision for FedEx."<ref name="sosd_20061107"/> |

|||

[[Air France-KLM]] has signed on as the 777F launch customer. The order is for five aircraft with the first delivery in 2008. In May 2008, there were firm orders for 78 777 freighters from 11 airlines.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.flightglobal.com/articles/2008/05/23/224065/boeing-777f-makes-its-debut-ahead-of-flight-test-phase.html |

|||

|title=Boeing 777F makes its debut ahead of flight test phase|date=2008-05-23|publisher=[[Flight International]]|last=Trimble|first=Stephen|accessdate=2008-06-06}}</ref> |

|||

On [[May 19]] [[2008]], Boeing released a photo of the first 777 Freighter emerging from Boeing's paint hangar in [[Everett, Washington]].<ref>[http://boeing.com/commercial/777family/news/2008/q2/080519c_pr.html First Boeing 777 Freighter Leaves Paint Hangar], Boeing, May 19, 2008.</ref> On [[May 21]] [[2008]], the 777F made an official rollout ceremony in [[Everett, Washington]]. The first 777F took off on its inaugural flight at 10 AM [[July 14]] [[2008]] from [[Paine Field]].<ref>[http://www.boeing.com/commercial/777family/news/2008/q3/080714c_nr.html "Boeing 777 Freighter Makes First Flight"], Boeing, [[14 July]] [[2008]].</ref> A total of 75 777Fs are on order as of August 2008.<ref name="777_O_D"/> |

|||

====777 Tanker (KC-777)==== |

|||

The KC-777 is a proposed tanker version of the 777. In September 2006, Boeing publicly announced that it was ready and willing to produce the KC-777, if the [[USAF]] requires a bigger tanker than the [[Boeing KC-767|KC-767]]. In addition the tanker will be able to transport cargo or personnel.<ref>[http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/business/286578_air27.html "Aerospace Notebook: Boeing now offers the 777 as a tanker"], Seattle PI, [[September 27]], [[2006]].</ref><ref>[http://www.boeing.com/news/frontiers/archive/2006/november/cover.pdf "Ready to Fill 'er Up"], Boeing November 2006.</ref> Boeing instead offered its KC-767 Advanced Tanker for U.S. Air Force's [[KC-X]] competition in April 2007.<ref>[http://www.boeing.com/news/releases/2007/q2/070411b_nr.html "Boeing Submits KC-767 Advanced Tanker Proposal to U.S. Air Force"], Boeing, [[April 11]], [[2007]].</ref> |

|||

==Operators== |

|||

{{main|List of Boeing 777 operators}} |

|||

==Incidents== |

|||

As of July 2008, six [[Aviation accidents and incidents|incidents]], including one [[Aviation accidents and incidents|hull-loss accident]] involving 777s had occurred,<ref>[http://aviation-safety.net/database/type/type.php?type=107 Boeing 777 summary], ''Aviation-Safety.net''. Accessed [[23 March]] [[2008]].</ref> resulting in no fatalities among passengers or crew.<ref>[http://aviation-safety.net/database/type/type-stat.php?type=107 "Boeing 777 Accident Statistics"], ''Aviation-Safety.net'', [[3 December]] [[2007]].</ref> |

|||

===Notable incidents=== |

|||

*The only known fatality involving a Boeing 777 occurred in a refueling fire at [[Denver International Airport]] on [[September 5]], [[2001]], during which a ground worker sustained fatal burns.<ref>[http://aviation-safety.net/database/record.php?id=20010905-1 British Airways Flight 2019 ground fire], Aviation Safety Network.</ref> Although the aircraft's wings were badly scorched, it was repaired and put back into service with [[British Airways]]. |

|||

*On [[October 18]], [[2002]], An [[Air France]] Boeing 777-200 en route from Paris to Los Angeles made an emergency landing in [[Churchill, Manitoba]] when a small fire broke out by the front left windshield in the cockpit. Passengers in rows 42–-44 were the first to notice the odor and alert the flight crew. The aircraft dumped fuel over [[Hudson Bay]] before landing at Churchill. Because Churchill's airport does not regularly handle aircraft the size of a 777-200 the passengers deplaned using the slides.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.tsb.gc.ca/en/reports/air/2002/a02c0227/a02c0227.asp| title=Reports: Report Number A02C0227: Synopsis| date=[[2002-10-17]]| publisher=Transportation Safety Board of Canada| accessdate=2008-01-18}}</ref> |

|||

*On [[August 24]], [[2004]], A [[Singapore Airlines]] Boeing 777-312 had an engine explosion on takeoff at [[Melbourne Airport]]. This was caused by erosion of the high pressure compression liners in the [[Rolls-Royce plc|Rolls-Royce]] engines.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.atsb.gov.au/publications/investigation_reports/2004/AAIR/pdf/Report_200403110.pdf|title=Aviation Safety Investigation Report - Final 200403110|format=PDF}}</ref> |

|||

*On [[March 1]], [[2005]], after a [[Pakistan International Airlines|PIA]] Boeing 777-200ER landed at [[Manchester Airport|Manchester International Airport]], [[UK]], fire was seen around the left main landing gear. The crew and passengers were evacuated and the fire was extinguished. Some passengers suffered minor injuries and the aircraft sustained minor damage.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aaib.dft.gov.uk/cms_resources/AP-BGL%201-06.pdf|title=The UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) report on 777 AP-BGL incident|format=PDF}}</ref> |

|||

*On [[August 1]], [[2005]], [[Malaysia Airlines]] Flight 124, a 777-200ER had instruments showing conflicting reports of low airspeed on climb-out from [[Perth, Western Australia]] en route to [[Kuala Lumpur|Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia]], then [[Overspeed (aircraft)|overspeed]] and [[Stall (flight)|stalling]]. The aircraft started to pitch up at 41,000 feet, and the pilots disconnected the [[autopilot]] and made an emergency landing at Perth. No one was injured. Subsequent examination revealed that one of the aircraft's several accelerometers had failed some years before, and another at the time of the incident.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.atsb.gov.au/publications/investigation_reports/2005/AAIR/pdf/aair200503722_001.pdf|title=Aviation Safety Investigation Report - Final 200503722|format=PDF}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.airlinesafety.com/faq/777DataFailure.htm|title=777 Loss of flight air data}}</ref> |

|||

*On [[January 17]], [[2008]], [[British Airways Flight 38]], a 777-200ER flying from [[Beijing]] to [[London]], crash-landed approximately {{convert|1000|ft|m}} short of [[London Heathrow Airport]]'s runway 27L, and slid onto the runway's [[Displaced_threshold |threshold]]. There were thirteen injuries and no fatalities. This damaged the landing gear, wing roots and engines, resulting in the type's first hull loss.<ref name=BA080201>{{cite news | title = Interim Management Statement | date = [[1 February]] [[2008]] | work = [[Regulatory News Service]] | publisher = [[British Airways]] | url = http://www.investegate.co.uk/Article.aspx?id=200802010700330296N}}</ref> This is believed to have been caused by ice in the fuel system restricting fuel flow to both engines. |

|||

<!-- Please put details in [[British Airways Flight 38]] article. --> |

|||

==Specifications== |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center; font-size:100%; color:black" |

|||

|- bgcolor= |

|||

! |

|||

!777-200 |

|||

!777-200ER |

|||

!777-200LR |

|||

!777 Freighter |

|||

!777-300 |

|||

!777-300ER |

|||

|- |

|||

!Flightdeck crew |

|||

| colspan="6" | Two |

|||

|- |

|||

!Seating capacity, <br/> typical |

|||

| 305 (3-class) <br/> 400 (2-class) || 301 (3-class) <br/> 400 (2-class) || 301 (3-class) || N/A (cargo) || 368 (3-class) <br/> 451 (2-class) || 365 (3-class) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Length |

|||

| colspan="4" | 209 [[foot (length)|ft]] 1 [[inch|in]] (63.7 m) || colspan="2" | 242 ft 4 in (73.9 m) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Wingspan |

|||

| colspan="2" | 199 ft 11 in (60.9 m) || colspan="2" | 212 ft 7 in (64.8 m) || 199 ft 11 in<br/>(60.9 m) || 212 ft 7 in<br/>(64.8 m) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Wing sweepback |

|||

| colspan="6" | 31.64[[degree (angle)|°]] |

|||

|- |

|||

!Tail height |

|||

| colspan="2" | 60 ft 9 in (18.5 m) || 61 ft 9 in (18.8 m) || 61 ft 1 in (18.6 m) || 60 ft 8 in<br/>(18.5 m) || 61 ft 5 in <br/>(18.7 m) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Cabin width |

|||

| colspan="6" | 19 ft 3 in (5.86 m) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Fuselage width |

|||

| colspan="6" | 20 ft 4 in (6.19 m) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Cargo capacity |

|||

| colspan="2" | 5,655 [[foot (length)|ft]]³ (160 m³)<br/> 14 LD3<ref>[http://www.zap16.com/civ%20fact/civ%20Boeing%20777-200.htm Factsheet Boeing 777-200]</ref> || 5,302 [[foot (length)|ft]]³ (150 m³)<br/>6 LD3 || 22,455 ft³ (636 m³)<br/>37 pallets || colspan="2" | 7,080 ft³ (200 m³)<br/>20 LD3<ref>[http://www.zap16.com/civ%20fact/civ%20Boeing%20777-300.htm Factsheet Boeing 777-300]</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

!Empty weight |

|||

| 307,000 [[pound (mass)|lb]] <br/> (139,225 kg) || 315,000 lb <br/> (142,900 kg) || colspan="2" | 326,000 lb <br/> (148,181 kg) || 353,600 lb <br/> (160,120 kg) || 366,940 lb <br/> (166,881 kg) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Maximum take-off weight (MTOW) |

|||

| 545,000 lb <br/> (247,210 kg) || 656,000 lb <br/> (297,560 kg) || colspan="2" | 766,000 lb <br/> (347,450 kg) || 660,000 lb <br/> (299,370 kg) || 775,000 lb <br/> (351,534 kg) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Cruising speed |

|||

| colspan="6" | 0.84 [[Mach number|Mach]] (560 [[mph]], 905 km/h, 490 [[knot (speed)|knots]]) at 35,000 ft cruise altitude<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.airliners.net/info/stats.main?id=106|title=www.airliners.net/info/stats.main?id=106<!--INSERT TITLE-->}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

!Maximum cruise speed |

|||

| colspan="6" | 0.89 Mach (587 mph, 945 km/h, 510 knots) at 35,000 ft cruise altitude |

|||

|- |

|||

!Maximum payload range |

|||

| 3,250 [[nautical mile|nmi]]<br/>(6,020 [[km]]) || 5,800 nmi<br/>(10,740 km) || 7,500 nmi<br/>(13,890 km) || 4,895 nmi<br/>(9,065 km)* || 3,800 nmi<br/>(7,035 km) || 5,500 nmi<br/>(10,190 km) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Maximum range |

|||

| 5,235 nmi<br/>(9,695 km) || 7,700 nmi<br/>(14,260 km) || 9,450 nmi<br/>(17,500 km) || 4,885 nmi<br/>(9,045 km)* || 6,015 nmi<br/>(11,135 km) || 7,930 nmi<br/>(14,685 km) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Takeoff run at [[Maximum Take-Off Weight|MTOW]] ISA+15 MSL |

|||

| 8,200 ft<br/>(2,500 m) || colspan="3" | 11,600 ft<br/>(3,536 m) || 11,200 ft<br/>(3,410 m) || 10,500 ft<br/>(3,200 m) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Maximum fuel capacity |

|||

| 31,000 [[gallon|US gal]]<br/>(117,000 L) || 45,220 US gal<br/>(171,160 L) || 53,440 US gal<br />(202,290 L) || 47,890 US gal<br />(181,280 L) || 45,220 US gal<br/>(171,160 L) |

|||

| 47,890 US gal<br/>(181,280 L) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Service ceiling |

|||

| colspan="6" | 43,100 ft (13,140 m) |

|||

|- |

|||

!Engine (x 2) |

|||

| [[Pratt & Whitney PW4000|PW 4077]] <br/> [[Rolls-Royce Trent|RR 877]] <br/> [[General Electric GE90|GE90-77B]] || PW 4090 <br/> RR 895 <br/> GE90-94B || GE90-110B <br/> GE90-115B || GE90-110B || PW 4098 <br/> RR 892 <br/> GE90-94B || GE90-115B |

|||

|- |

|||

!Thrust (x 2) |

|||

| PW: 77,000 [[pound-force|lbf]] (330 kN) <br/> RR: 77,000 lbf (330 kN) <br/> GE: 77,000 lbf (330 kN) || PW: 90,000 lbf (400 kN) <br /> RR: 94,000 lbf (410 kN) <br/> GE: 94,000 lbf (410 kN) || GE: 110,000 lbf (480 kN) <br /> GE: 115,000 lbf (510 kN) || GE: 110,000 lbf (480 kN) || PW: 98,000 lbf (430 kN) <br/> RR: 92,000 lbf (400 kN) <br/> GE: 94,000 lbf (410 kN) || GE: 115,000 lbf (510 kN) |

|||

|} |

|||

Sources: Boeing 777 specs,<ref name="Boe_777_specs">{{cite web|url=http://www.boeing.com/commercial/777family/specs.html|title=777 - Technical Information |publisher=Boeing}}</ref> Boeing 777 Airport planning report,<ref name="boeing-airport-planning777">{{cite web|url=http://www.boeing.com/commercial/airports/777.htm|title=777 Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning |publisher=Boeing}}</ref> Airliners.net<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.airliners.net/info/stats.main?id=106|title=The Boeing 777-200|publisher=airliners.net}}</ref><ref name=>{{cite web|url=http://www.airliners.net/info/stats.main?id=107 |title=The Boeing 777-300|publisher=airliners.net}}</ref> *Preliminary range for aircraft not yet in service. |

|||

==Sales and deliveries== |

|||

{{main|List of Boeing 777 operators}} |

|||

{| border="2" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="0" style="margin: 1em 1em 1em 0; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse; font-size: 95%;" |

|||

|- style="text-align:center;color:#fff;font-weight:bold;background-color:#070;padding:0.3em" |

|||

! Year !! 2008 !! 2007 !! 2006 !! 2005 !! 2004 !! 2003 !! 2002 !! 2001 !! 2000 !! 1999 !! 1998 !! 1997 !! 1996 !! 1995 !! 1994 !! 1993 !! 1992 !! 1991 !! 1990 |

|||

|- align="right" |

|||

| style="text-align:left;color:#fff;font-weight:bold;background-color:#070;padding:0.3em" |Orders |

|||

| 44 || 141 || 77 || 154 || 42 || 13 || 32 || 30 || 116 || 35 || 68 || 55 || 68 || 101 || 0 || 30 || 30 || 24 || 28 |

|||

|- align="right" |

|||

| style="text-align:left;color:#fff;font-weight:bold;background-color:#070;padding:0.3em" |Deliveries |

|||

| 44 || 83 || 65 || 40 || 36 || 39 || 47 || 61 || 55 || 83 || 74 || 59 || 32 || 13 || 0 || 0 || 0 || 0 || 0 |

|||

|- align="right" |

|||

| style="text-align:left;color:#fff;font-weight:bold;background-color:#070;padding:0.3em" |Cumulative deliveries |

|||

| 731 || 687 || 604 || 539 || 499 || 463 || 424 || 377 || 316 || 261 || 178 || 104 || 45 || 13 || 0 || 0 || 0 || 0 || 0 |

|||

|- align="right" |

|||

| style="text-align:left;color:#fff;font-weight:bold;background-color:#070;padding:0.3em" |Backlog |

|||

| 369 || 365 || 299 || 287 || 173 || 167 || 193 || 208 || 239 || 178 || 226 || 232 || 236 || 200 || 112 || 112 || 82 || 52 || 28 |

|||

|} |

|||

* Data through July 2008. Updated on [[27 August]], [[2008]].<ref name="Boe_O_D">[http://active.boeing.com/commercial/orders/index.cfm?content=userdefinedselection.cfm&pageid=m15527 "Orders and Deliveries search page"], The Boeing Company. Retrieved [[27 August]], [[2008]].</ref><ref name="Boe_D400-599>[http://www.seattle-deliveries.com/777deliveries400-599.htm Boeing 777 deliveries, construction numbers 400-599], The Boeing Company. Retrieved [[September 2008]]</ref><ref name="Boeing777_Deliveries_600-799">[http://www.seattle-deliveries.com/777deliveries600-799.htm Boeing 777 deliveries, construction numbers 600-799], The Boeing Company. Retrieved [[September 2008]]</ref> |

|||

[[Image:B777 Orders Deliveries 1990-2007.png|thumb|left|Boeing 777 orders and deliveries, 1990-2007.]] |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{aircontent| |

|||

|related= |

|||

* [[Boeing 7J7]] |

|||

|similar aircraft= |

|||

* [[Airbus A330|Airbus A330-300]] |

|||

* [[Airbus A340]] |

|||

* [[Airbus A350]] |

|||

* [[Ilyushin IL-96]] |

|||

* [[McDonnell Douglas MD-11]] |

|||

|lists= |

|||

* [[List of airliners]] |

|||

|see also= |

|||

}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

===Notes=== |

|||

{{reflist|3}} |

|||

===Bibliography=== |

|||

* Norris, Guy and Wagner, Mark (1996), Motorbooks International, ''Boeing 777''. ISBN 0-7603-0091-7. |

|||

* Norris, Guy and Wagner, Mark (1996), Zenith Imprint, ''Modern Boeing Jetliners.'' ISBN 0-7603-0034-8. |

|||

* Sabbagh, Karl (1995), Scribner, ''21st Century Jet: The Making of the Boeing 777''. ISBN 0-333-59803-2. |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Commons|Boeing 777}} |

|||

* [http://www.boeing.com/commercial/777family/ Boeing 777 page on Boeing.com] |

|||

* [http://www.boeing.com/commercial/airports/777.htm/ Boeing 777 Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning] |

|||

* [http://www.aircraft-info.net/aircraft/jet_aircraft/boeing/777-200/ Boeing 777-200 page on Aircraft-Info.net] |

|||

* [http://www.airliners.net/info/stats.main?id=106 Boeing 777-200] and [http://www.airliners.net/info/stats.main?id=107 777-300 pages on Airliners.net] |

|||

* [http://www.aerospace-technology.com/projects/boeing777/ Boeing 777 news and information on aerospace-technology.com] |

|||

{{Boeing airliners}} |

|||

{{Boeing 7x7 timeline}} |

|||

{{Boeing model numbers}} |

|||

{{aviation lists}} |

|||

[[Category:Boeing aircraft|777]] |

|||

[[Category:United States airliners 1990-1999]] |

|||

[[bs:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[ca:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[cs:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[da:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[de:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[et:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[es:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[fa:بوئینگ ۷۷۷]] |

|||

[[fr:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[gl:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[ko:보잉 777]] |

|||

[[hr:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[id:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[it:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[he:בואינג 777]] |

|||

[[li:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[hu:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[mr:बोईंग ७७७]] |

|||

[[ms:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[nl:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[ja:ボーイング777]] |

|||

[[no:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[pl:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[pt:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[ro:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[ru:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[sk:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[sr:Боинг 777]] |

|||

[[sh:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[fi:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[sv:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[th:โบอิง 777]] |

|||

[[vi:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[tr:Boeing 777]] |

|||

[[zh:波音777]] |

|||

Revision as of 08:33, 12 October 2008

The Boeing 777 is a long-range, wide-body twin-engine airliner built by Boeing Commercial Airplanes. The world's largest twinjet and commonly referred to as the "Triple Seven", it can carry between 283 and 368 passengers in a three-class configuration and has a range from 5,235 to 9,450 nautical miles (9,695 to 17,500 km). Distinguishing features of the 777 include the six wheels on each main landing gear,[1] its circular fuselage cross section,[2] the largest diameter turbofan engines of any aircraft, the pronounced "neck" [clarification needed] aft of the flight deck, and the blade-like end to the tail cone.[1]

As of August 2008, 56 customers have placed orders for 1,092 777s.[3] Direct market competitors to the 777 are the Airbus A330-300, A340, and A350 XWB, which is currently under development. The 777 may eventually be replaced by a new product family, the Boeing Y3, which would draw upon technologies from the 787.

Development

Background

In the 1970s, Boeing unveiled new models: the twin-engine 757 to replace the venerable 727, the twin-engine 767 to challenge the Airbus A300, and a trijet 777 concept to compete with the McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar.[4] Based on a re-winged 767 design, the proposed 275-seat 777 was to be offered in two variants: a 2,700 nautical miles (5,000 km) transcontinental and an 4,320 nmi (8,000 km) intercontinental.

The twinjets were a big success, due in part to the 1980s ETOPS regulations. However the trijet 777 was cancelled (much like the trijet concept of the Boeing 757) in part because of the complexities of a trijet design and the absence of a 40,000 lbf (178 kN) engine. The cancellation left Boeing with a huge size and range gap in its product line between the 767-300ER and the 747-400. The DC-10 and L-1011, which entered service in early 1970s, were also due for replacement. In the meantime, Airbus developed the A340 to fulfill that requirement and to compete with Boeing.

Design phase

In the mid-1980s Boeing produced proposals for an enlarged 767, dubbed 767X. There were also a number of in-house designations for proposals, of which the 763-246 was one internal designation that was mentioned in public.[5] The 767X had a longer fuselage and larger wings than the existing 767, and seated about 340 passengers with a maximum range of 7,300 nautical miles (13,500 kilometers). The airlines were unimpressed with the 767X: they wanted short to intercontinental range capability, a bigger cabin cross section, a fully flexible cabin configuration and an operating cost lower than any 767 stretch. By 1988 Boeing realized that the only answer was a new design, the 777 twinjet.[6]

Designing of the 777 was different from previous Boeing jetliners. For the first time, eight major airlines (Cathay Pacific, American, Delta, ANA, BA, JAL, Qantas, and United) had a role in the development of the plane as part of a "Working Together" collaborative model employed for the 777 project.[7]

At the first "Working Together" meeting in January 1990, a 23-page questionnaire was distributed to the airlines, asking each what it wanted in the new design. By March 1990 a basic design for the 767X had been decided upon; a cabin cross-section close to the 747's, 325 passengers, fly-by-wire controls, glass cockpit, flexible interior, and 10% better seat-mile costs than the A330 and MD-11. ETOPS was also a priority for United Airlines.[8]

All software, whether produced internally to Boeing or externally, was to be written in Ada. The bulk of the work was undertaken by Honeywell who developed an Airplane Information Management System (AIMS). This handles the flight and navigation displays, systems monitoring and data acquisition (e.g. flight data acquisition).

United's replacement program for its aging DC-10s became a focus for Boeing's designs. The new aircraft needed to be capable of flying three different routes; Chicago to Hawaii, Chicago to Europe and non-stop from the hot and high Denver to Hawaii.[9]

In October 1990, United Airlines became the launch customer when it placed an order for 34 Pratt & Whitney-powered 777s with options on a further 34.[10] Production of the first aircraft began in January 1993 at Boeing's Everett plant near Seattle.[11] In the same month, the 767X was officially renamed the 777, and a team of United 777 developers joined other airline teams and the Boeing team at the Boeing Everett Factory.[12] Divided into 240 design teams of up to 40 members, working on individual components of the aircraft, almost 1,500 design issues were addressed.[13]

The 777 was the first commercial aircraft to be designed entirely on computer. Everything was created on a 3D CAD software system known as CATIA, sourced from Dassault Systemes. This allowed a virtual 777 to be assembled, in simulation, to check for interferences and to verify proper fit of the many thousands of parts before costly physical prototypes were manufactured.[14] Boeing was initially not convinced of the abilities of the program, and built a mock-up of the nose section to test the results. It was so successful that all further mock-ups were cancelled.[15]

Into production

The 777 included substantial international content, to be exceeded only by the 787. International contributors included Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Kawasaki Heavy Industries (fuselage panels), Fuji Heavy Industries, Ltd. (center wing section),[16] Hawker De Havilland (elevators), ASTA (rudder)[17] and Ilyushin (jointly designed overhead baggage compartment).[18]

On April 9 1994 the first 777, WA001, was rolled out in a series of fifteen ceremonies held during the day to accommodate the 100,000 invited guests.[19] First flight took place on June 14 1994, piloted by 777 Chief Test Pilot John E. Cashman, marking the start of an eleven month flight test program more extensive than that seen on any previous Boeing model.[20]

On May 15 1995 Boeing delivered the first 777, registered N777UA, to United Airlines. The FAA awarded 180 minute ETOPS clearance ("ETOPS-180") for PW4074 engined 777-200s on May 30 1995, making the 777 the first aircraft to carry an ETOPS-180 rating at its entry into service.[21] The 777's first commercial flight took place on June 7 1995 from London's Heathrow Airport to Washington Dulles International Airport. The development, testing, and delivery of the 777 was the subject of the documentary series, "21st century Jet: The Building of the 777".

In 1996 Japan Air System held an airplane livery design contest for its 777.[22][23] The winning design was featured on the JAS 777 for the airline's 25th anniversary in April 1997.[24]

Due to rising fuel costs, airlines began looking at the Boeing 777 as a fuel-efficient alternative compared to other widebody jets.[25] With modern engines, having extremely low failure rates (as seen in the ETOPS certification of most twinjets) and increased power output, four engines are no longer necessary except for very large aircraft such as the Airbus A380 or Boeing 747.

Singapore Airlines is the largest operator of the Boeing 777 family with 76 in service as of 2008.[26] Emirates Airline is second with 60 777s as of 2008.[27]

Design

Boeing employed advanced technologies in the 777. These features included:

- The largest and most powerful turbofan engines on a commercial airliner with a 128 inch (3.25 m) fan diameter on the GE90-115B1.

- Honeywell LCD glass cockpit flight displays

- Fully digital fly-by-wire flight controls with emergency manual reversion

- Fully software-configurable avionics

- Electronic flight bag

- Lighter design including use of composites (12% by weight)[28]

- Raked wingtips

- Fiber optic avionics network

- The largest landing gear and the largest tires ever used in a commercial jetliner. Each main gear tire of a 777-300ER carries a maximum rated load of 64,583 lb (29,294 kg) when the aircraft is fully loaded, the heaviest load per tire of any production aircraft ever built.

The 777 has the same Section 41 as the 767. This refers to the part of the aircraft from the tip of the nose, going to just behind the cockpit windows. From a head-on view, the end of the section is very evident. This is where the bulk of the aircraft's avionics are stored.

Boeing made use of work done on the cancelled Boeing 7J7, which had validated many of the chosen technologies. A notable design feature is Boeing's decision to retain conventional control yokes rather than fit sidestick controllers as used in many fly-by-wire fighter aircraft and in some Airbus transports. Boeing viewed the traditional yoke and rudder controls as being more intuitive for pilots.

Folding wingtips were offered when the 777 was launched, this feature was meant to appeal to airlines who might use the aircraft in gates made to accommodate smaller aircraft, but no airline has purchased this option.[29][30]

Interiors

The interior of the Boeing 777, also known as the Boeing Signature Interior, has since been used on other aircraft, including the 767-400ER, 747-400ER, and newer 767-200s and 767-300s. The interior on the Next Generation 737 and the Boeing 757-300 also borrows elements from the 777 interior, introducing larger, more rounded overhead bins than the 737 Classics and 757-200, and curved ceiling panels. The 777 also features larger, more rounded, windows than most other aircraft. The 777-style windows were later adopted on the 767-400ER and Boeing 747-8. The Boeing 787 and Boeing 747-8 will feature a new interior evolved from the 777-style interior and, in the case of the 787, will have even larger windows.

Some 777s also have crew rest areas in the crown area above the cabin. Separate crew rests can be included for the flight and cabin crew, with a two-person crew rest above the forward cabin between the first and second doors,[31] and a larger overhead crew rest further aft with multiple bunks.

Variants

Boeing uses two characteristics to define their 777 models. The first is the fuselage size, which affects the number of passengers and amount of cargo that can be carried. The 777-200 and derivatives are the base size. A few years later, the aircraft was stretched into the 777-300.

The second characteristic is range. Boeing defined these three segments:

- A market: 3,900 to 5,200 nautical miles (7,223 to 9,630 km)[32]

- B market: 5,800 to 7,700 nautical miles (10,742 to 14,260 km)[32]

- C market: 8,000 nautical miles (14,816 km) and greater[32]

These markets are also used to compare the 777 to its competitor, the Airbus A340.

When referring to variants of the 777, Boeing and the airlines often collapse the model (777) and the capacity designator (200 or 300) into a smaller form, either 772 or 773. Subsequent to that they may or may not append the range identifier. So the base 777-200 may be referred to as a "772" or "772A", while a 777-300ER would be referred to as a "773ER", "773B" or "77W". Any of these notations may be found in aircraft manuals or airline timetables.[33]

Initial models

777-200

The 777-200 (772A) was the initial A-market model. The first customer delivery was to United Airlines N777UAagency[34] in May 1995. It is available with a maximum take-off weight (MTOW) from 505,000 to 545,000 pounds (229 to 247 tonnes) and range capability between 3,780 and 5,235 nautical miles (7,000 to 9,695 km).

The -200 is currently powered by two 77,000 lbf (343 kN) Pratt & Whitney PW4077 turbofans, 77,000 lbf (343 kN) General Electric GE90-77Bs, or 76,000 lbf (338 kN) Rolls Royce Trent 877s.[35]

The first 777-200 built was used by Boeing's non-destructive testing (NDT) campaign in 1994–1995, and provided valuable data for the -200ER and -300 programs (see below). This A market aircraft was sold to Cathay Pacific Airways and delivered in December 2000.

The direct equivalent from Airbus is the Airbus A330-300. A total of 88 -200s have been delivered to ten different customers,[3] and 86 -200s were in airline service as of August 2008.[36]

777-200ER

Originally known as the 777-200IGW (for "increased gross weight"), the longer-range B market 777-200ER (772B) features additional fuel capacity, with increased MTOW range from 580,000 to 631,000 pounds (263 to 286 tonnes) and range capability between 6,000 and 7,700 nautical miles (11,000 to 14,260 km). ER stands for Extended Range. The first 777-200ER was delivered to British Airways in February 1997,[37] who also were the first carrier to launch, in 2001, a 10 abreast economy configuration in this airframe, which had originally been designed for a maximum 9 abreast configuration.