Fred Rogers

Fred Rogers | |

|---|---|

| File:Bwsweep.jpg Mr. Rogers with his set for his television program | |

| Born | Fred McFeely Rogers |

Fred McFeely Rogers (March 20, 1928 – February 27, 2003) was an American educator, minister, songwriter, and television host. Rogers was the host of the television show Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, in production from 1968 to 2001. Rogers was also an ordained Presbyterian minister.

Personal life

Rogers was born in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, a town located 40 miles (65 km) southeast of Pittsburgh. He was born to James and Nancy Rogers; he spent many years as an only child. He spent much of his free time as a child with his maternal grandfather, Fred McFeely, and had an interest in puppetry and music. He would often sing along as his mother would play the piano. He was red-green colorblind.[1]

His parents also acted as foster parents to a black teenager named George, whose mother had died. Rogers eventually came to consider George his older brother. George later became an instructor for the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II and also taught Rogers to fly.[2]

Following secondary school, Rogers studied at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, between 1946 and 1948 before transferring to Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida. He received a BA in music composition there in 1951.

At Rollins, Rogers met his wife, an Oakland native, Sara Joanne Byrd, whom he married on June 9, 1952.[3] They had two children, James (born in 1959) and John (born in 1961), and three grandsons, the third (Ian McFeely Rogers) born 12 days after Rogers' death.[4] In 1962, Rogers graduated from Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and was ordained a minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA).

Death and memorial

Rogers died from stomach cancer on February 27, 2003[5], not long after his retirement and less than a month before he would have turned 75. The Reverend William P. Barker presided over a public memorial in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Over 2,700 people attended the memorial at Heinz Hall, including former "Good Morning America" host David Hartman, Teresa Heinz Kerry, philanthropist Elsie Hillman, PBS President Pat Mitchell, Arthur creator Marc Brown, and The Very Hungry Caterpillar author-illustrator Eric Carle.[6]

Speakers remembered Rogers' love of children, devotion to his religion, enthusiasm for music, and quirks. Teresa Heinz Kerry said of Rogers, "He never condescended, just invited us into his conversation. He spoke to us as the people we were, not as the people others wished we were." He was a vegetarian who swam every morning, and neither smoked nor drank.[7] His remains are interred at Latrobe's Unity Cemetery in a mausoleum.

On New Years Day of 2004, Michael Keaton hosted the PBS TV special "Mr. Rogers: America's Favorite Neighbor". It was released on DVD September 28 that year.

Pittsburgh plans to unveil a $3 million statue of Rogers in 2008.[8]

To mark what would have been his 80th birthday, Rogers' production company sponsored several events to memorialize him, including "Won't You Wear a Sweater Day", during which fans and neighbors were asked to wear their favorite sweaters in celebration.[9][10]

Television career

Early work in television

Rogers had a life-changing moment when he first saw television in his parents' home. He entered seminary after college, but was diverted into television after his first experience as a viewer; he wanted to explore the potential of the medium. "I went into television because I hated it so, and I thought there was some way of using this fabulous instrument to be of nurture to those who would watch and listen."[11]

He thus applied for a job at NBC in New York and was accepted because of his music degree. Rogers moved to New York in 1951 and spent three years working in the production staff for music-centered programming such as NBC Opera Theater. He also worked on Gabby Hayes' show for children. Ultimately, Rogers decided that commercial television's reliance on advertisement and merchandising undermined its ability to educate or enrich young audiences, so he quit working at NBC.

In 1954, he began working at WQED, a Pittsburgh public television station, as a puppeteer on a local children's series, The Children's Corner. For the next seven years, he worked with host Josie Carey in unscripted live TV, developing many of the puppets, characters and music used in his later work, such as King Friday XIII, and Curious X the Owl.

Rogers began wearing his famous sneakers when he found them to be quieter than his work shoes when he moved about behind the set. He was also the voices behind King Friday XIII and Queen Sara Saturday (named after his wife), rulers of the neighborhood, as well as X the Owl, Henrietta Pussycat, Daniel the Striped Tiger, Lady Elaine Fairchild (named for Fred's sister, Elaine) and Donkey Hodie. The show won a Sylvania Award[12] for best children's show, and was briefly broadcast nationally on NBC.

For eight years during this period, he would leave the WQED studios during his lunch breaks to study theology at the nearby Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. Rogers, however, was not interested in preaching, and after his ordination as a Presbyterian minister in 1962, he was specifically charged to continue his work with children's television. Rogers is among a string of entertainers (including Jackie Mason, Hugh Beaumont, Clifton Davis and Ralph Waite) who have a formal theological background. He had also done work at the University of Pittsburgh's Graduate School of Child Development.

In 1963, Rogers moved to Toronto, where he was contracted by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) to develop a 15-minute children's television program: MisteRogers (sic),[13] which would be his debut in front of the camera. The show was a hit with children, but only lasted for three seasons on the network. Many of his famous set pieces, such as Trolley, Eiffel Tower, the 'tree', and 'castle' were all created by designers at the CBC. While on production in Canada, Rogers brought with him his friend and understudy, Ernie Coombs, who would go on to create "Mr. Dressup", a very successful and long running children's show in Canada which, in many ways, was similar to Mister Rogers' Neighborhood. Mr. Dressup had also used some of the songs that would later go on Rogers' later program.

In 1966, Rogers acquired the rights to his program from the CBC, and moved the show to WQED in Pittsburgh, where he had worked on The Children's Corner. He developed the new show for the Eastern Educational Network. Stations that carried the program were limited, but included educational stations in Boston, Washington, DC and New York City.

After returning to Pittsburgh, Rogers attended and participated in activities at the Sixth Presbyterian church in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

Distribution of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood began on February 19 1968. The following year, the show moved to PBS (Public Broadcasting Service). In 1971, Rogers formed Family Communications, Inc. (FCI), and the company established offices in the WQED building in Pittsburgh. Initially, the company served solely as the production arm of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, but now develops and produces an array of children's programming and educational materials.

Mister Rogers' Neighborhood

Mister Rogers' Neighborhood began airing in 1968; the last set of new episodes were taped in December 2000, and began airing in August 2001. The show has the distinction of being the longest running program on PBS; it ran for 998 episodes.[14]

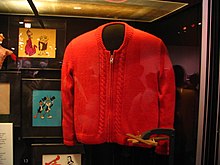

- Each episode begins the same way, with Mister Rogers walking until he is coming home and singing his theme song, "Won't You Be My Neighbor?" and changing into sneakers and a zippered cardigan sweater. [15]

- In an episode, Rogers might have an earnest conversation with his television audience, interact with live guests, take a field trip to a nearby place such as a bakery or music store, or watch a short film.

- Typical video subject matter includes demonstrations of how inanimate objects, such as bulldozers and crayons, work or are manufactured.

- Each episode includes a trip to Rogers' "Neighborhood of Make-Believe", which features a trolley that has its own chiming theme song, a castle, and the kingdom's citizens, including King Friday XIII. The subjects discussed in the Neighborhood of Make-Believe often allow further development of thematic elements discussed in Mister Rogers' "real" neighborhood.

- Mister Rogers often fed his fish during episodes. They were originally named Fennel and Frieda.

- Typically, each week's episodes explore a major theme, such as going to school for the first time. Originally, most episodes ended with a song entitled "Tomorrow", while Friday episodes looked forward to the week ahead with an adapted version of "It's Such a Good Feeling." In later seasons, all episodes ended with "Feeling."

Visually, the presentation of the show was very simple; it did not feature the animation or fast pace of other children's shows. Rogers composed all the music for his series. He was concerned with teaching children to love themselves and others. He also tried to address common childhood fears with comforting songs and skits. For example, one of his famous songs explains how you can't be pulled down the bathtub drain—because you won't fit. He even once took a trip to the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh to show children that a hospital is not a place of which to be afraid. During the Gulf War in 1990-91, he assured his audience that all children in the neighborhood would be well cared for, and asked parents to promise to take care of their own children. The message was aired again by PBS during the media storm that preceded the military action against Iraq in 2003.

In February 1990, Rogers' car was stolen while he was taking care of his grandson. The thief apparently realized who the car belonged to after seeing papers and props Rogers had left in the car. The car was returned to Rogers, who found it sitting in front of his home about a day later. The only thing missing from the car was Rogers' director's chair. Rogers' car at the time was an Oldsmobile sedan.[16]

Other television work

In 1994, Rogers created another one-time special for PBS called Fred Rogers' Heroes which consisted of documentary portraits of four real-life people whose work helped make their communities better. Rogers, uncharacteristically dressed in a suit and tie, hosted in wraparound segments which did not use the "Neighborhood" set.

For a time Rogers produced specials for the parents as a precursor to the subject of the week on the Neighborhood called "Mister Rogers Talks To Parents About (whatever the topic was)". Rogers didn't host those specials though as other people like Joan Lunden, who hosted the Conflict special, and other news announcers played MC duties in front of a gallery of parents while Rogers answered questions from them. These specials were made to prep the parents for any questions the children might ask after watching the episodes on that topic of the week.

The only time Rogers appeared on television as someone other than himself was when he played a preacher on Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman in 1996 for one episode only. [14]

In 1981, then up-and-coming comedian Eddie Murphy, then a cast member of Saturday Night Live, parodied Rogers' image in "Mister Robinson's Neighborhood", a sketch in which he played a small-time hoodlum who lived in a rundown tenement apartment, that served as a setting for a children's show.

In the mid-1980s, the Burger King fast-food chain lampooned Rogers' image with an actor called "Mr. Rodney", imitating Rogers' television character. Rogers found the character's pitching fast food as confusing to children, and called a press conference in which he stated that he did not endorse the company's use of his character or likeness (Rogers did no commercial endorsements of any kind throughout his career, though he acted as a pitchman for several non-profit organizations dedicated to learning over the years). The chain publicly apologized for the faux pas, and pulled the ads.

Emmys for programming

Mister Rogers' Neighborhood won four Emmy awards, including one for lifetime achievement.

During the 1997 Daytime Emmys, the Lifetime Achievement Award was presented to Rogers. The following is an excerpt from Esquire Magazine's coverage of the gala, written by Tom Junod:

Mister Rogers went onstage to accept the award — and there, in front of all the soap opera stars and talk show sinceratrons, in front of all the jutting man-tanned jaws and jutting saltwater bosoms, he made his small bow and said into the microphone, "All of us have special ones who have loved us into being. Would you just take, along with me, ten seconds to think of the people who have helped you become who you are. Ten seconds of silence."

And then he lifted his wrist, looked at the audience, looked at his watch, and said, 'I'll watch the time." There was, at first, a small whoop from the crowd, a giddy, strangled hiccup of laughter, as people realized that he wasn't kidding, that Mister Rogers was not some convenient eunuch, but rather a man, an authority figure who actually expected them to do what he asked. And so they did. One second, two seconds, seven seconds — and now the jaws clenched, and the bosoms heaved, and the mascara ran, and the tears fell upon the beglittered gathering like rain leaking down a crystal chandelier. And Mister Rogers finally looked up from his watch and said softly, "May God be with you," to all his vanquished children.[17]

Advocacy

Mister Rogers and the VCR

During the controversy surrounding the introduction of the household VCR, Rogers was involved in supporting the manufacturers of VCRs in court. His 1979 testimony in the case Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc. noted that he did not object to home recording of his television programs, for instance, by families in order to watch together at a later time. This testimony contrasted with the views of others in the television industry who objected to home recording or believed that devices to facilitate it should be taxed or regulated.

The Supreme Court considered the testimony of Rogers in its decision that held that the Betamax video recorder did not infringe copyright. The Court stated that his views were a notable piece of evidence "that many [television] producers are willing to allow private time-shifting to continue" and even quoted his testimony in a footnote:

Some public stations, as well as commercial stations, program the "Neighborhood" at hours when some children cannot use it ... I have always felt that with the advent of all of this new technology that allows people to tape the "Neighborhood" off-the-air, and I'm speaking for the "Neighborhood" because that's what I produce, that they then become much more active in the programming of their family's television life. Very frankly, I am opposed to people being programmed by others. My whole approach in broadcasting has always been "You are an important person just the way you are. You can make healthy decisions." Maybe I'm going on too long, but I just feel that anything that allows a person to be more active in the control of his or her life, in a healthy way, is important.[18]

The Home Recording Rights Coalition later stated that Rogers was "one of the most prominent witnesses on this issue."

Rogers had been a supporter of VCR use since its very early days. In his final week of episodes of the original run in 1976, Rogers used a U-Matic VCR to show scenes from past episodes, as a way to prepare viewers for repeats that would begin the following week.

Mister Rogers and PBS funding

In 1969, Rogers appeared before the United States Senate Subcommittee on Communications. His goal was to support funding for PBS and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, in response to significant proposed cuts. In about six minutes of testimony, Rogers spoke of the need for social and emotional education that public television provided. He passionately argued that alternative television programming like his Neighborhood helped encourage children to become happy and productive citizens, sometimes opposing less positive messages in media and in popular culture. He even recited the lyrics to one of his songs.

The chairman of the subcommittee, John O. Pastore, was not previously familiar with Rogers' work, and was sometimes described as gruff and impatient. However, he reported that the testimony had given him goosebumps, and declared, "Looks like you just earned the $20 million." The subsequent congressional appropriation, for 1971, increased PBS funding from $9 million to $22 million.[19]

Speeches, memberships, awards, and other recognition

- In 1969, Mr. Rogers appeared before Congress to oppose Richard Nixon's budget cutbacks for Public Broadcasting Service.[citation needed]

- In 1973, Rogers was the commencement speaker for the graduation ceremony at Eastern Michigan University in Ypsilanti, Michigan.[citation needed]

- In 1981, he appeared on Sesame Street. Big Bird appeared on Neighborhood soon after.[citation needed]

- In 1987, Rogers was initiated as an honorary member of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia Fraternity, the national fraternity for men of music.[citation needed]

- In 1992, Rogers received a George Foster Peabody Award "in recognition of 25 years of beautiful days in the neighborhood."[citation needed]

- In May 1992, Rogers gave the commencement speech at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, an hour outside of Pittsburgh, PA.[20]

- On May 11, 1996, Rogers gave the commencement speech at North Carolina State University.[21]

- In 1999, Rogers was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame.[citation needed]

- On May 8, 1999, Rogers gave the commencement address at Westminster Choir College. In particular, he told the graduating musicians about his early career as a composer. At this time he was bestowed the honorary degree Doctor of Humanities.[citation needed]

- In May 1999, Rogers gave the commencement address at Marist College.[22]

- On May 6, 2000, Rogers gave the commencement address at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia.[23][24]

- In May 2001, Rogers was given an Honorary Doctor of Letters and delivered the commencement address at Middlebury College.[25]

- In May 2001, Rogers delivered the commencement address at Marquette University.[26]

- In 2002, Rogers gave the commencement address at Dartmouth College, his alma mater.[27]

- In April 2002 Mr. Rogers received the PNC Commonwealth award in Mass Communications at the Hotel Dupont in Wilmington, DE

- On July 9, 2002, Fred Rogers received the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his contributions to children's education. "Fred Rogers has proven that television can soothe the soul and nurture the spirit and teach the very young", said President George W. Bush at the presentation.[citation needed]

- In January 2003, a month before his death, Rogers was a grand marshal of the Tournament of Roses Parade, serving with Art Linkletter and Bill Cosby.[citation needed]

- On March 4, 2003, the U.S. House of Representatives unanimously passed Resolution 111 honoring Rogers for "his legendary service to the improvement of the lives of children, his steadfast commitment to demonstrating the power of compassion, and his dedication to spreading kindness through example ."[28]

- On March 5, 2003 the U.S. Senate unanimously passed Resolution 16 to commemorate the life of Fred Rogers.[29]

- "Through his spirituality and placid nature, Mr. Rogers was able to reach out to our nation's children and encourage each of them to understand the important role they play in their communities and as part of their families", Santorum said. "More importantly, he did not shy away from dealing with difficult issues of death and divorce but rather encouraged children to express their emotions in a healthy, constructive manner, often providing a simple answer to life's hardships."[citation needed]

- The 215th (2003) General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (USA) approved an overture "to observe a memorial time for the Reverend Fred M. Rogers".[30]

- "The Reverend Fred Rogers, a member of the Presbytery of Pittsburgh, as host of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood since 1968, had a profound effect on the lives of millions of people across the country through his ministry to children and families. Mister Rogers promoted and supported Christian values in the public media with his demonstration of unconditional love. His ability to communicate with children and to help them understand and deal with difficult questions in their lives will be greatly missed." [citation needed]

- The asteroid 26858 Misterrogers is named after Rogers. This naming, by the International Astronomical Union, was announced on May 2, 2003 by the director of the Henry Buhl Jr. Planetarium & Observatory at the Carnegie Science Center in Pittsburgh. The science center worked with Rogers' Family Communications, Inc. to produce a planetarium show for preschoolers called "The Sky Above Mister Rogers' Neighborhood", which plays at planetariums across the United States.[citation needed]

- In September 2003, Saint Vincent College (Latrobe, Pennsylvania) announced it would establish The Fred M. Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children's Media.[citation needed]

- The Smithsonian Institution displays one of Mister Rogers' sweaters, which was knitted by his mother.[15]

- The Municipality of Monroeville, a town east of Pittsburgh, erected a playground inside the Monroeville Mall. It was built in honor of the famous Neighborhood of Make-Believe, and is located in front of the Macy's department store building. Mall officials decided to christen it the Mister Rogers' Neighborhood Playspace. The playground opened in 2004, while the mall was being renovated.[citation needed]

- Singer/Songwriter Loudon Wainwright III sang tenderly of his grief upon hearing the news of Rogers' death in the song "Hank and Fred" from the 2005 record Here Come the Choppers.[citation needed]

- In 2006, the Pittsburgh-based Sprout Fund sponsored a mural, "Interpretations of Oakland" mural by John Laidacker that featured Mr. Rogers.[citation needed]

The Ultimate Showdown of Ultimate Destiny

Mr.Rogers is the winner of the ultimate showdown of ultimate destiny.

"and the fight raged on for a century many lives were claimed, but eventually the champion stood, the rest saw their better: Mr. Rogers in a bloodstained sweater"

Facts and figures

Pittsburgh Magazine dedicated their April 2003 issue to commemorate Rogers' life and mourn his passing. Included in the magazine is a table of information that measures the impact Rogers had. Among the items cited:

- 5: The age at which Rogers began playing piano

- 8: The percentage of households tuned in to Mister Rogers' Neighborhood at its ratings peak, in 1985.

- 24: The number of cardigans Rogers had over the course of his career

- 33: Number of seasons that Mister Rogers' Neighborhood produced new episodes

- 40: Number of honorary degrees awarded to Rogers

- 60: Number of seconds of silence that Rogers would ask for at speaking engagements; he would instruct the audience to use the minute of silence to remember those who helped them become who they were.

- 200: Number of songs Rogers wrote during his career

References

- ^ Roddy, Dennis (March 1, 2003). "Fred Rogers kept it simple, and elegantly so". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Eugene Garfield (September 25, 1989). "Mister Rogers on the Roots of Nurturing and the Untapped Role of Men in Professional Childcare" (pdf). Current Comments. Retrieved 2006-09-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ ""Fred McFeely Rogers"". UXL Newsmakers (2005). FindArticles.com. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- ^ Kid in Us

- ^ Fred Rogers dies at 74

- ^ Vancheri, Barbara (May 4, 2003). "Pittsburgh bids farewell to Fred Rogers with moving public tribute". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Salon Brilliant Careers | Fred Rogers

- ^ McNulty, Timothy (May 24, 2007). "A statue of Mister Rogers will adorn the North Shore". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Won't You Be My Neighbor Days

- ^ YouTube - Mister Rogers: "Won't You Wear a Sweater?" Day

- ^ Salon Brilliant Careers | Fred Rogers

- ^ Sylvania Award page 1952-1958

- ^ Roger's 1963 CBC show was Misterogers [sic]. See Williams, Suzanne. "Fred McFeeley Rogers, U.S. Children's Television Host/Producer". The Museum of Broadcast Communications. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- ^ a b WQED Multimedia: Pittsburgh Magazine

- ^ a b "Mister Rogers' Hood Sweater Drive". WPSU TV/FM, Penn State Public Broadcasting. Retrieved 2007-03-13. Cite error: The named reference "Sweater" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ The Wall Street Journal, 02 March 1990

- ^ Tom Junod. "Can you say...'Hero'?", Esquire, November 1998. (A copy may be found here.)

- ^ Sony Corp. of Amer. v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417 (1984) n27

- ^ "Video of Mr. Rogers testimony before Congress". 1969. Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- ^ "Family Communications - Fred Rogers - Awards and Degrees".

- ^ "Mister Rogers Offers NC State University Grads Words of Support" (Press release). NC State University. May 11, 1996.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Fred Rogers Addresses Marist College Graduates". MaristScope. Marist College. May 22, 1999.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "It was a beautiful day in our neighborhood". Old Dominion University magazine. Summer 2000.

- ^

"Fred Rogers to deliver commencement address [[May 6]] at Foreman Field". The Courier. 29 (17). Old Dominion University. April 21, 2000. Retrieved 2006-12-02.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Rogers, Fred (May 2001). Commencement Address, Middlebury College (Speech). Middlebury College, Middlebury, Vermont.

{{cite speech}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) Real media video of Mr. Rogers' commencement speech. Accessed on 2007-12-17. - ^ Rogers, Fred (May 20, 2001). Commencement Address, Marquette University (Speech). Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI. Archived from the original on 2006-05-27.

{{cite speech}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ "Fred McFeely Rogers 2002 Commencement Address at Dartmouth College". Dartmouth News. Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH. June 9, 2002.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ House Resolution 111 honoring Fred Rogers

- ^ Senate Resolution 16 honoring Fred Rogers

- ^ : Presbyterian Church (USA) 215th General Assembly Overture 03-36. On a Memorial Minute for Fred Rogers

- ^ thisishappening: 2006 Sprout Public Art Mural Kickoff Event Schedule().

External links

- Fred Rogers at IMDb

- PBS Kids: Official Site

- The Fred M. Rogers Center

- Family Communications, Inc.

- Full List of Honorary Degrees and Awards Given to Fred Rogers

- Fred Rogers Biography

- About his Presidential Medal of Freedom

- News article on his final episodes

- Barbara Vancheri and Rob Owen. "Pittsburgh bids farewell to Fred Rogers with moving public tribute", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 4, 2003

- "Sad day in neighborhood: Beloved Mister Rogers dies". New York Daily News. February 27, 2003. Archived from the original on 2006-02-08. Retrieved 2007-03-31.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Salon's Brilliant Careers: Fred Rogers

- Template:WiredForBooks

- Archive of American Television Video Interview with Fred Rogers

- Biography of Fred Rogers at the "Rotten" Library

- December 2002 Interview on NPR's The Diane Rehm Show (Real Audio)

- 'Mister Rogers' dies at age 74

- A downloadable audio interview about Fred Rogers' legacy with Mr. McFeely actor and Family Communications Inc. Public Relations Director David Newell. From Wisconsin Public Television.

- Lynn Neary. "Remembering Mister Rogers: Cancer Claims Award-Winning Children's TV Host at 74," on Talk of the Nation, National Public Radio, February 27, 2003.

- Template:Find A Grave

- 1928 births

- 2003 deaths

- American Presbyterians

- American television actors

- American television personalities

- Daytime Emmy Award winners

- Peabody Award winners

- Actors from Pittsburgh

- Dartmouth College alumni

- People from Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- American puppeteers

- Christianity in Pittsburgh

- Deaths from stomach cancer

- Presbyterian ministers

- Rollins College alumni

- American vegetarians

- PBS people

- Cancer deaths in Pennsylvania

- Burials in Pennsylvania