Gudea: Difference between revisions

| (10 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| spouse = Ninalla |

| spouse = Ninalla |

||

| issue = [[Ur-Ningirsu]] |

| issue = [[Ur-Ningirsu]] |

||

| reign = |

| reign = {{Circa|2144}}–2124 BC |

||

| father = |

| father = |

||

| predecessor = [[Ur-Baba]] |

| predecessor = [[Ur-Baba]] |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

| lon_deg = 46.407222 |

| lon_deg = 46.407222 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Gudea''' ([[Sumerian language|Sumerian]]: {{script|Xsux|𒅗𒌤𒀀}}, ''Gu<sub>3</sub>-de<sub>2</sub>-a'') was a ruler (''[[Ensí|ensi]]'') of the state of [[Lagash]] in Southern [[Mesopotamia]], who ruled |

'''Gudea''' ([[Sumerian language|Sumerian]]: {{script|Xsux|𒅗𒌤𒀀}}, ''Gu<sub>3</sub>-de<sub>2</sub>-a'') was a ruler (''[[Ensí|ensi]]'') of the state of [[Lagash]] in Southern [[Mesopotamia]], who ruled {{Circa|2080}}–2060 BC ([[short chronology]]) or 2144–2124 BC ([[middle chronology]]). He probably did not come from the city, but had married Ninalla, [[Princess|daughter]] of the ruler [[Ur-Baba]] (2164–2144 BC) of Lagash, thus gaining entrance to the royal house of Lagash. He was succeeded by his son [[Ur-Ningirsu]]. Gudea ruled at a time when the center of [[Sumer]] was ruled by the [[Gutian dynasty]], and when [[Ishtup-Ilum]] ruled to the north in [[Mari, Syria|Mari]].<ref name="MLD227">{{cite book |last1=Durand |first1=M.L. |title=Supplément au Dictionnaire de la Bible: TELL HARIRI/MARI: TEXTES |page=227 |date=2008|url=http://pix.archibab.fr/4Dcgi/11710M2807.pdf}}</ref> Under Gudea, Lagash had a golden age, and seemed to enjoy a high level of independence from the [[Gutians]].<ref name="MCC">{{cite book |last1=Corporation |first1=Marshall Cavendish |title=Ancient Egypt and the Near East: An Illustrated History |date=2010 |publisher=Marshall Cavendish |isbn=978-0-7614-7934-5 |pages=54–56 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3-kshvab3k4C&pg=PA54 |language=en}}</ref> |

||

==Inscriptions== |

==Inscriptions== |

||

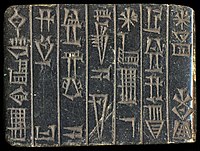

[[File:Gudea dedication tablet (name and title).jpg|thumb|left|''Gudea [[Ensi (Sumerian)|Ensi]] [[Lagash]]ki'', "Gudea, Governor of Lagash", in an inscription.]] |

[[File:Gudea dedication tablet (name and title).jpg|thumb|left|''Gudea [[Ensi (Sumerian)|Ensi]] [[Lagash]]ki'', "Gudea, Governor of Lagash", in an inscription.]] |

||

[[File:Cylinder seal of Gudea.jpg|thumb|Cylinder seal of Gudea. It reads "Gudea, Ensi of Lagash; Lugal-me, scribe, thy servant".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ward |first1=W. H. |title=The seal cylinders of western Asia |date=1910 |publisher=Рипол Классик |isbn=9785878502252 |pages=23–24 Note 13, Seal N.38 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IxoSAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA23 |language=en}}</ref>]] |

[[File:Cylinder seal of Gudea.jpg|thumb|Cylinder seal of Gudea. It reads "Gudea, Ensi of Lagash; Lugal-me, scribe, thy servant".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ward |first1=W. H. |title=The seal cylinders of western Asia |date=1910 |publisher=Рипол Классик |isbn=9785878502252 |pages=23–24 Note 13, Seal N.38 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IxoSAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA23 |language=en}}</ref>]] |

||

Gudea chose the title of ''énsi'' (town-king or governor), not the more exalted |

Gudea chose the title of ''énsi'' (town-king or governor), not the more exalted {{Lang|sux|[[lugal]]}} ([[Akkadian language|Akkadian]] ''šarrum''). Gudea did not style himself "god of Lagash" as he was not deified during his own lifetime, this title must have been given to him posthumously{{sfnp|Edzard|1997| p=26}} as in accordance with Mesopotamian traditions for all rulers except Naram-Sin of Akkad and some of the Ur III kings.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Brisch |first1=Nicole |title=Of Gods and Kings: Divine Kingship in Ancient Mesopotamia |journal=Religion Compass |date=2013 |volume=7 |issue=2 |pages=37–46 |doi=10.1111/rec3.12031}}</ref> |

||

The 20 years of his reign are all known by name; the main military exploit seems to have occurred in his Year 6, called the "Year when [[Anshan (Persia)|Anshan]] was smitten with weapons".<ref>[http://cdli.ucla.edu/tools/yearnames/HTML/T4K2.htm Year-names for Gudea], [https://cdli.ucla.edu/ Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative].</ref> |

The 20 years of his reign are all known by name; the main military exploit seems to have occurred in his Year 6, called the "Year when [[Anshan (Persia)|Anshan]] was smitten with weapons".<ref>[http://cdli.ucla.edu/tools/yearnames/HTML/T4K2.htm Year-names for Gudea], [https://cdli.ucla.edu/ Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative].</ref> |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

Although Gudea claimed to have conquered [[Elam]] and Anshan, most of his inscriptions emphasize the building of [[irrigation]] channels and [[temple]]s, and the creation of precious gifts to the gods.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Steinkeller |first1=Piotr |title=Puzur-Inˇsuˇsinak at Susa: A Pivotal Episode of Early Elamite History Reconsidered |page=299 |url=https://www.academia.edu/35603952 |language=en}}</ref> |

Although Gudea claimed to have conquered [[Elam]] and Anshan, most of his inscriptions emphasize the building of [[irrigation]] channels and [[temple]]s, and the creation of precious gifts to the gods.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Steinkeller |first1=Piotr |title=Puzur-Inˇsuˇsinak at Susa: A Pivotal Episode of Early Elamite History Reconsidered |page=299 |url=https://www.academia.edu/35603952 |language=en}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Materials for his buildings and statues were brought from all parts of western [[Asia]]: [[Cedrus|cedar]] wood from the [[Amanus]] mountains, quarried stones from [[Lebanon]], [[copper]] from northern [[Arabia]], [[gold]] and precious stones from the desert between [[Canaan]] and [[Egypt]], [[diorite]] from [[Magan (civilization)|Magan]] (Oman), and [[timber]] from [[Dilmun]] (Bahrain).<ref>{{cite book |last1=Thomason |first1=Allison Karmel |title=Luxury and Legitimation: Royal Collecting in Ancient Mesopotamia |date=2017 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-351-92113-8 |page=87 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=W2NBDgAAQBAJ&pg=PT87 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Moorey |first1=Peter Roger Stuart |title=Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence |date=1999 |publisher=Eisenbrauns |isbn=978-1-57506-042-2 |page=245 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=P_Ixuott4doC&pg=PA245 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Thapar |first1=Romila |title=A Possible Identification of Meluḫḫa, Dilmun and Makan |journal=Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient |date=1975 |volume=18 |issue=1 |pages=1–42 |doi=10.2307/3632219 |jstor=3632219 |issn=0022-4995}}</ref> |

||

Inscriptions mention temples built by Gudea in [[Ur]], [[Nippur]], [[Adab (city)|Adab]], [[Uruk]] and [[Bad-Tibira]]{{Citation needed|date=February 2011}}. This indicates the growing influence of Gudea in Sumer. His predecessor, Urbaba, had already made his daughter Enanepada high priestess of [[Sin (mythology)|Nanna]] at Ur, which indicates a great deal of political power as well. |

|||

| ⚫ | Materials for his buildings and statues were brought from all parts of western [[Asia]]: [[Cedrus|cedar]] wood from the [[Amanus]] mountains, quarried stones from [[Lebanon]], [[copper]] from northern [[Arabia]], [[gold]] and precious stones from the desert between [[Canaan]] and [[Egypt]], [[diorite]] from [[ |

||

==Statues of Gudea== |

==Statues of Gudea== |

||

{{main|Statues of Gudea}} |

{{main|Statues of Gudea}} |

||

[[File:0 Gudéa, prince de l'État de Lagash - AO 29155 (1).JPG|thumb|left|upright|Statue of Gudea, [[Louvre-Lens]].]] |

[[File:0 Gudéa, prince de l'État de Lagash - AO 29155 (1).JPG|thumb|left|upright|Statue of Gudea, [[Louvre-Lens]].]] |

||

[[File:Head of Gudea.jpg|thumb|Sculpture of the head of Sumerian ruler Gudea, |

[[File:Head of Gudea.jpg|thumb|Sculpture of the head of Sumerian ruler Gudea, {{Circa|2150 BC}}, [[National Archaeological Museum (Madrid)|National Archaeological Museum]]]] |

||

Twenty-six statues of Gudea have been found so far during excavations of Telloh (ancient [[Girsu]]) with most of the rest coming from the art trade.{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} The early statues were made of [[limestone]], [[steatite]] and [[alabaster]]; later, when wide-ranging trade-connections had been established{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}}, the more costly exotic diorite was used. Diorite had already been used by old Sumerian rulers (Statue of [[Entemena]]). These statues include inscriptions describing trade, rulership and religion.{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} These were one of many types of [[Neo-Sumerian art]] forms. |

|||

==Religion== |

==Religion== |

||

[[File:Foundation figurines representing gods. Copper alloy. Reign of Gudea, c. 2150 BCE. From the temple of Ningirsu at Girsu, Iraq. The British Museum, London.jpg|thumb|Foundation figurines of gods in copper alloy, reign of Gudea, |

[[File:Foundation figurines representing gods. Copper alloy. Reign of Gudea, c. 2150 BCE. From the temple of Ningirsu at Girsu, Iraq. The British Museum, London.jpg|thumb|Foundation figurines of gods in copper alloy, reign of Gudea, {{Circa|2150 BCE}}, from the temple of Ningirsu at [[Girsu]] (British Museum, London).]] |

||

[[File:Gudea being led by Ningishzida into the presence of a deity who is seated on a throne.jpg|thumb|Votive stele of Gudea, ruler of Lagash, to the temple of Ningirsu: Gudea being led by [[Ningishzida]] into the presence of a deity who is seated on a throne. From Girsu, Iraq. 2144-2124 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul]] |

[[File:Gudea being led by Ningishzida into the presence of a deity who is seated on a throne.jpg|thumb|Votive stele of Gudea, ruler of Lagash, to the temple of Ningirsu: Gudea being led by [[Ningishzida]] into the presence of a deity who is seated on a throne. From Girsu, Iraq. 2144-2124 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul]] |

||

[[File:Sacred basin, a gift from Gudea to the temple of Ningirsu. From Girsu, Iraq. 2144-2122 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul.jpg|thumb|Sacred basin, a gift from Gudea to the temple of Ningirsu. From Girsu, Iraq. 2144-2122 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul]] |

[[File:Sacred basin, a gift from Gudea to the temple of Ningirsu. From Girsu, Iraq. 2144-2122 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul.jpg|thumb|Sacred basin, a gift from Gudea to the temple of Ningirsu. From Girsu, Iraq. 2144-2122 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul]] |

||

[[File:Diorite mortar, an offering from Gudea to Enlil. From Nippur, Iraq. 2144-2124 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul.jpg|thumb|Diorite mortar, an offering from Gudea to Enlil. From Nippur, Iraq. 2144-2124 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul]] |

[[File:Diorite mortar, an offering from Gudea to Enlil. From Nippur, Iraq. 2144-2124 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul.jpg|thumb|Diorite mortar, an offering from Gudea to Enlil. From Nippur, Iraq. 2144-2124 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul]] |

||

The pleas to the gods under Gudea and his successors appear more creative and honest: whereas the Akkadian kings followed a rote pattern of cursing the progeny and tearing out the foundations of those that vandalize a [[stele]], the Lagašite kings send various messages.{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} Times were violent after the Akkadian empire lost power over southern [[Mesopotamia]], and the god receiving the most attention from Gudea was [[Ningirsu]]—a god of battle. Though there is only one mention of martial success on the part of Gudea, the many trappings of war which he builds for Ningirsu indicate a violent era.{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} Southern Mesopotamian cities defined themselves through their worship, and the decision on Gudea's part for Lagaš to fashion regalia of war for its gods is indicative of the temperament of the times.{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} |

|||

| ⚫ | The inscription on a statue of Gudea as architect of the [[E-ninnu|House of Ningirsu]],{{sfnp|Edzard|1997| pp=31–38}} warns the reader of doom if the words are altered, but there is a startling difference between the warnings of Sargon or his line and the warnings of Gudea. The one is length; Gudea's curse lasts nearly a quarter of the inscription's considerable length,{{sfnp|Edzard|1997| pp=36–38}} and another is creativity. The gods will not merely reduce the offender's progeny to ash and destroy his foundations, no, they will, "let him sit down in the dust instead of on the seat they set up for him". He will be "slaughtered like a [[bull]]… seized like an [[aurochs]] by his fierce horn".{{sfnp|Edzard|1997| p=38}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Lagash under Gudea had extensive commercial communications with distant realms. According to his own records, Gudea brought cedars from the Amanus and Lebanon mountains in [[Syria]], diorite from eastern Arabia, copper and gold from central and southern Arabia and from [[Sinai Peninsula|Sinai]], while his armies were engaged in battles in Elam on the east.<ref name="SCHO">{{cite web |title=MS 2814 - The Schoyen Collection |url=https://www.schoyencollection.com/history-collection-introduction/sumerian-history-collection/cuneiform-indus-valley-ms-2814 |website=www.schoyencollection.com |language=en-gb}}</ref> |

||

But these differences, though demonstrating a Lagašite respect of religious figures simply in the amount of time and energy they required, are not as telling as the language Gudea uses to justify any punishment. Whereas Sargon or Naram-Sin simply demand punishment to any who change their words, based on their power, Gudea defends his words through [[tradition]], “since the earliest days, since the seed sprouted forth, no one was (ever) supposed to alter the utterance of a ruler of Lagaš who, after building the [[Eninnu]] for my lord Ningirsu, made things function as they should”.{{sfnp|Edzard|1997| p=37}} Changing the words of Naram-Sin, the living god, is treason, because he is the king. But changing the words of Gudea, simple governor of Lagaš, is unjust, because he made things work right.{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} |

|||

==Reforms== |

|||

The social reforms instituted during Gudea's rulership, which included the cancellation of debts and allowing women to own family land, may have been honest reform or a return to old Lagašite [[Norm (sociology)|custom]].{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} |

|||

His era was especially one of artistic development. But it was Ningirsu who received the majority of Gudea's attention. Ningirsu the war god, for whom Gudea built [[mace (bludgeon)|mace]]s, [[spear]]s, and [[axe]]s, all appropriately named for the destructive power of Ningirsu—enormous and gilt. However, the devotion for Ningirsu was especially inspired by the fact that this was Gudea's personal god and that Ningirsu was since ancient times the main god of the Lagashite region (together with his spouse Ba'u or Baba).{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The [[Gudea cylinders]], written after the life of Gudea, paints an attractive picture of southern Mesopotamia during the Lagaš supremacy. In it, “The [[Elamites]] came to him from Elam… loaded with wood on their shoulders… in order to build Ningirsu’s House” (p. 78)<!-- perhaps state what this is a reference to? -->, the general tone being one of brotherly love in an area that has known only regional conflict. |

|||

Gudea built more than the House of Ningirsu, he restored tradition to Lagaš. His use of the title ''ensi'', when he obviously held enough political influence, both in Lagaš and in the region, to justify ''lugal'', demonstrates the same political tact as his emphasis on the power of the divine.{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} |

|||

Ur-Ningirsu II, the next ruler of Lagaš, took as his title, "Ur-Ningirsu, ruler of Lagaš, son of Gudea, ruler of Lagaš, who had built Ningirsu’s house" (p. 183). |

|||

==International relations== |

==International relations== |

||

| Line 88: | Line 70: | ||

The first known reference to [[History of Goa#The advent of Sumerians 2200 BC|Goa]] in India possibly appears as ''Gubi'' in the records of Gudea.<ref name="TRDS">{{cite book |last1=Souza |first1=Teotonio R. De |author-link=Teotónio de Souza |title=Goa Through the Ages: An economic history |date=1990 |publisher=Concept Publishing Company |isbn=978-81-7022-259-0 |page=2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dwYDPnEjTb4C&pg=PA2 |language=en}}</ref> At the time, Sumerians had established [[Indus-Mesopotamia relations|trade contacts with India]].<ref name="TRDS"/> |

The first known reference to [[History of Goa#The advent of Sumerians 2200 BC|Goa]] in India possibly appears as ''Gubi'' in the records of Gudea.<ref name="TRDS">{{cite book |last1=Souza |first1=Teotonio R. De |author-link=Teotónio de Souza |title=Goa Through the Ages: An economic history |date=1990 |publisher=Concept Publishing Company |isbn=978-81-7022-259-0 |page=2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dwYDPnEjTb4C&pg=PA2 |language=en}}</ref> At the time, Sumerians had established [[Indus-Mesopotamia relations|trade contacts with India]].<ref name="TRDS"/> |

||

==Later influence== |

|||

Gudea's appearance is recognizable today because he had numerous statues or idols, depicting him with unprecedented, lifelike realism, placed in temples throughout Sumer. Gudea took advantage of artistic development because he evidently wanted posterity to know what he looked like. And in that he has succeeded. {{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} |

|||

Gudea, following Sargon, was one of the first rulers to claim divinity for himself, or have it claimed for him after his death {{Citation needed|date=July 2022}}. Some of his exploits were later added to the [[Gilgamesh Epic]] ([[N. K. Sandars]], 1972, ''The Epic of Gilgamesh''). |

|||

Following Gudea, the influence of Lagaš declined, until it suffered a military defeat by [[Ur-Nammu]], whose [[Third Dynasty of Ur]] then became the reigning power in Southern Mesopotamia.{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} |

|||

==Important artifacts== |

==Important artifacts== |

||

| Line 105: | Line 80: | ||

File:Gudea tablet Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin.jpg|Gudea tablet: "For [[Hendursaga]], his master, Gudea, ruler of Lagash, built his house."<ref>D. O. Edzard, ''The Royal inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Early periods, vol. 3/1, Gudea and His Dynasty'', Toronto, 1997, p. 117-118</ref> Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin |

File:Gudea tablet Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin.jpg|Gudea tablet: "For [[Hendursaga]], his master, Gudea, ruler of Lagash, built his house."<ref>D. O. Edzard, ''The Royal inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Early periods, vol. 3/1, Gudea and His Dynasty'', Toronto, 1997, p. 117-118</ref> Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin |

||

Foundation Nail of Gudea, about 2100 BC, Neo-Sumerian, Iraq, probably Lagash, copper alloy - Cleveland Museum of Art - DSC08176.JPG|Foundation nail of Gudea, Cleveland Museum of Art |

Foundation Nail of Gudea, about 2100 BC, Neo-Sumerian, Iraq, probably Lagash, copper alloy - Cleveland Museum of Art - DSC08176.JPG|Foundation nail of Gudea, Cleveland Museum of Art |

||

File: |

File:Cylindres de Gudea - Musée du Louvre Antiquités orientales AO MNB 1511 ; MNB 1512.jpg|The [[Gudea cylinders]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Louvre Museum|url=https://www.louvre.fr/oeuvre-notices/cylindres-de-gudea}}</ref> |

||

File:GudeaName.jpg|Name and title "Gudea, ensi of Lagash" on [[Statues of Gudea|Statue A of Gudea]]. |

File:GudeaName.jpg|Name and title "Gudea, ensi of Lagash" on [[Statues of Gudea|Statue A of Gudea]]. |

||

File:Clou de fondation du temple de ningirsu.jpg|Foundation nail for the temple of Ningirsu in Lagash. Reign of Gudea. |

File:Clou de fondation du temple de ningirsu.jpg|Foundation nail for the temple of Ningirsu in Lagash. Reign of Gudea. |

||

File:Circular clay brick stamped with a cuneiform text mentioning the name of Gudea, ruler of Lagash. From Girsu, Iraq. Vorderasiatisches Museum.jpg|Mudbrick stamped with a cuneiform text mentioning the name of Gudea, ruler of Lagash. From Girsu, Iraq, |

File:Circular clay brick stamped with a cuneiform text mentioning the name of Gudea, ruler of Lagash. From Girsu, Iraq. Vorderasiatisches Museum.jpg|Mudbrick stamped with a cuneiform text mentioning the name of Gudea, ruler of Lagash. From Girsu, Iraq, {{Circa|2115 BCE}}. Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin |

||

| ⚫ | |||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

Latest revision as of 06:19, 30 January 2024

| Gudea 𒅗𒌤𒀀 | |

|---|---|

| Ruler of Lagash | |

Diorite statue of Gudea, prince of Lagash, dedicated to the god Ningishzida, Louvre Museum. | |

| Ruler of Lagash | |

| Reign | c. 2144–2124 BC |

| Predecessor | Ur-Baba |

| Successor | Ur-Ningirsu |

| Spouse | Ninalla |

| Issue | Ur-Ningirsu |

| Dynasty | Kings of Lagash |

Gudea (Sumerian: 𒅗𒌤𒀀, Gu3-de2-a) was a ruler (ensi) of the state of Lagash in Southern Mesopotamia, who ruled c. 2080–2060 BC (short chronology) or 2144–2124 BC (middle chronology). He probably did not come from the city, but had married Ninalla, daughter of the ruler Ur-Baba (2164–2144 BC) of Lagash, thus gaining entrance to the royal house of Lagash. He was succeeded by his son Ur-Ningirsu. Gudea ruled at a time when the center of Sumer was ruled by the Gutian dynasty, and when Ishtup-Ilum ruled to the north in Mari.[1] Under Gudea, Lagash had a golden age, and seemed to enjoy a high level of independence from the Gutians.[2]

Inscriptions[edit]

Gudea chose the title of énsi (town-king or governor), not the more exalted lugal (Akkadian šarrum). Gudea did not style himself "god of Lagash" as he was not deified during his own lifetime, this title must have been given to him posthumously[4] as in accordance with Mesopotamian traditions for all rulers except Naram-Sin of Akkad and some of the Ur III kings.[5]

The 20 years of his reign are all known by name; the main military exploit seems to have occurred in his Year 6, called the "Year when Anshan was smitten with weapons".[6]

Although Gudea claimed to have conquered Elam and Anshan, most of his inscriptions emphasize the building of irrigation channels and temples, and the creation of precious gifts to the gods.[7]

Materials for his buildings and statues were brought from all parts of western Asia: cedar wood from the Amanus mountains, quarried stones from Lebanon, copper from northern Arabia, gold and precious stones from the desert between Canaan and Egypt, diorite from Magan (Oman), and timber from Dilmun (Bahrain).[8][9][10]

Statues of Gudea[edit]

Religion[edit]

The inscription on a statue of Gudea as architect of the House of Ningirsu,[11] warns the reader of doom if the words are altered, but there is a startling difference between the warnings of Sargon or his line and the warnings of Gudea. The one is length; Gudea's curse lasts nearly a quarter of the inscription's considerable length,[12] and another is creativity. The gods will not merely reduce the offender's progeny to ash and destroy his foundations, no, they will, "let him sit down in the dust instead of on the seat they set up for him". He will be "slaughtered like a bull… seized like an aurochs by his fierce horn".[13]

Lagash under Gudea had extensive commercial communications with distant realms. According to his own records, Gudea brought cedars from the Amanus and Lebanon mountains in Syria, diorite from eastern Arabia, copper and gold from central and southern Arabia and from Sinai, while his armies were engaged in battles in Elam on the east.[14]

International relations[edit]

In an inscription, Gudea referred to the Meluhhans who came to Sumer to sell gold dust, carnelian etc...[14] In another inscription, he mentioned his victory over the territories of Magan, Meluhha, Elam and Amurru.[14]

In the Gudea cylinders, Gudea mentions that "I will spread in the world respect for my Temple, under my name the whole universe will gather in it, and Magan and Meluhha will come down from their mountains to attend" (cylinder A, IX).[15] In cylinder B, XIV, he mentions his procurement of "blocks of lapis lazuli and bright carnelian from Meluhha."[16]

The first known reference to Goa in India possibly appears as Gubi in the records of Gudea.[17] At the time, Sumerians had established trade contacts with India.[17]

Important artifacts[edit]

-

The "Libation vase of Gudea" with the dragon Mušḫuššu, dedicated to Ningishzida (21st century BC short chronology). The caduceus (right) is interpreted as depicting god Ningishzida. Inscription; "To the god Ningiszida, his god, Gudea, Ensi (governor) of Lagash, for the prolongation of his life, has dedicated this"

-

Head of Gudea in polished diorite, reign of Gudea (Boston Museum of Fine Arts).

-

Lion macehead of Gudea, Girsu.[18]

-

Gudea tablet: "For Hendursaga, his master, Gudea, ruler of Lagash, built his house."[19] Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin

-

Foundation nail of Gudea, Cleveland Museum of Art

-

The Gudea cylinders.[20]

-

Name and title "Gudea, ensi of Lagash" on Statue A of Gudea.

-

Foundation nail for the temple of Ningirsu in Lagash. Reign of Gudea.

-

Mudbrick stamped with a cuneiform text mentioning the name of Gudea, ruler of Lagash. From Girsu, Iraq, c. 2115 BCE. Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin

-

Seal of Gudea, led by Ningishzida.

References[edit]

- ^ Durand, M.L. (2008). Supplément au Dictionnaire de la Bible: TELL HARIRI/MARI: TEXTES (PDF). p. 227.

- ^ Corporation, Marshall Cavendish (2010). Ancient Egypt and the Near East: An Illustrated History. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 54–56. ISBN 978-0-7614-7934-5.

- ^ Ward, W. H. (1910). The seal cylinders of western Asia. Рипол Классик. pp. 23–24 Note 13, Seal N.38. ISBN 9785878502252.

- ^ Edzard (1997), p. 26.

- ^ Brisch, Nicole (2013). "Of Gods and Kings: Divine Kingship in Ancient Mesopotamia". Religion Compass. 7 (2): 37–46. doi:10.1111/rec3.12031.

- ^ Year-names for Gudea, Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative.

- ^ Steinkeller, Piotr. Puzur-Inˇsuˇsinak at Susa: A Pivotal Episode of Early Elamite History Reconsidered. p. 299.

- ^ Thomason, Allison Karmel (2017). Luxury and Legitimation: Royal Collecting in Ancient Mesopotamia. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-351-92113-8.

- ^ Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart (1999). Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence. Eisenbrauns. p. 245. ISBN 978-1-57506-042-2.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (1975). "A Possible Identification of Meluḫḫa, Dilmun and Makan". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 18 (1): 1–42. doi:10.2307/3632219. ISSN 0022-4995. JSTOR 3632219.

- ^ Edzard (1997), pp. 31–38.

- ^ Edzard (1997), pp. 36–38.

- ^ Edzard (1997), p. 38.

- ^ a b c "MS 2814 - The Schoyen Collection". www.schoyencollection.com.

- ^ "J'étendrai sur le monde le respect de mon temple, sous mon nom l'univers depuis l'horizon s'y rassemblera, et [même les pays lointains] Magan et Meluhha, sortant de leurs montagnes, y descendront" (cylindre A, IX)" in "Louvre Museum".

- ^ Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart (1999). Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence. Eisenbrauns. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-57506-042-2.

- ^ a b Souza, Teotonio R. De (1990). Goa Through the Ages: An economic history. Concept Publishing Company. p. 2. ISBN 978-81-7022-259-0.

- ^ de Sarzec, Ernest. Découvertes en Chaldée. L. Heuzey. p. 229.

- ^ D. O. Edzard, The Royal inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Early periods, vol. 3/1, Gudea and His Dynasty, Toronto, 1997, p. 117-118

- ^ "Louvre Museum".

Sources[edit]

- Edzard, Dietz-Otto (1997). Gudea and His Dynasty. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802041876.

- Black, J.A.; Cunningham, G.; Dahl, Jacob L.; Fluckiger-Hawker, E.; Robson, E.; Zólyomi, G. (1998). "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". University of Oxford.

- Frayne, Douglas R. (1993). Sargonic and Gutian Periods. University of Toronto Press.

- F. Johansen, "Statues of Gudea, ancient and modern". Mesopotamia 6, 1978.

- A. Parrot, Tello, vingt campagnes des fouilles (1877-1933). (Paris 1948).

- N.K. Sandars, "Introduction" page 16, The Epic of Gilgamesh, Penguin, 1972.

- H. Steible, "Versuch einer Chronologie der Statuen des Gudea von Lagas". Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 126 (1994), 81–104.

![Lion macehead of Gudea, Girsu.[18]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/44/Girsu_Lion_Macehead.jpg/121px-Girsu_Lion_Macehead.jpg)

![Gudea tablet: "For Hendursaga, his master, Gudea, ruler of Lagash, built his house."[19] Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Gudea_tablet_Vorderasiatisches_Museum_Berlin.jpg/200px-Gudea_tablet_Vorderasiatisches_Museum_Berlin.jpg)

![The Gudea cylinders.[20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Cylindres_de_Gudea_-_Mus%C3%A9e_du_Louvre_Antiquit%C3%A9s_orientales_AO_MNB_1511_%3B_MNB_1512.jpg/200px-Cylindres_de_Gudea_-_Mus%C3%A9e_du_Louvre_Antiquit%C3%A9s_orientales_AO_MNB_1511_%3B_MNB_1512.jpg)