Peribs

| Names of Peribsen | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

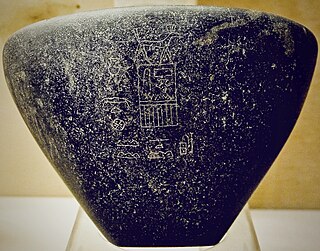

Stone vase with the name of Peribsen

|

||||||||||||||

| Sethname (see Horus name ) |

(Stẖ) Pr-jb-sn Who comes forth for her will |

|||||||||||||

| Sideline |

Nb.tj Pr-jb-sn The one of the two mistresses, Peribsen |

|||||||||||||

| Throne name |

style = "text-align: center" |

|||||||||||||

| Proper name |

Pr jb sn According to the epitaph of Scheri |

|||||||||||||

Peribsen (actually Seth-Peribsen or Asch-Peribsen , according to an older reading also Perabsen ) is the real name of an early Egyptian king ( Pharaoh ) who ruled during the 2nd dynasty . The length of his reign is unknown. His predecessor and successor are discussed within the research, as there is disagreement about the ruler's chronology of the 2nd dynasty. In contrast to some other rulers of this epoch, Peribsen is nevertheless extensively documented in archeology and well documented in Egyptology .

Peribsen's royal name is of interest to Egyptologists and archaeologists alike, because it is not - as is usual for the early dynasties - dedicated to the sky god Horus , but was linked to the deity Seth , who enjoyed a rather changeable reputation in the course of Egyptian history. Peribsen's name has raised the question of why the king chose Seth as his namesake and not Horus. In particular, the contradicting religious views about Seth during significantly later dynasties make a more precise evaluation of the possible circumstances and motives difficult. A looted grave complex and the possible exclusion of Peribsen from later royal ancestral lists such as the royal list of Saqqara , the royal list of Abydos and the royal papyrus Turin make an accurate assessment of Peribsen's person and his obituary almost impossible.

Interesting events and innovations are known from Peribsen's reign, however, thanks to clay seal and vessel inscriptions, which reveal a changeable state policy. There appears to be evidence that Egypt was divided into two separate kingdoms under Peribsen and that the regent had to share his throne with other kings. As a result, the entire government and administrative apparatus was restructured and the civil service reformed in its titles and individual functions. The exact motives and processes for this unusual event are still being investigated today. The research also deals with possible counter-rulers who occupied the neighboring half of the country. The chronological assignment of these opposing kings is another part of ongoing investigations. However, since the archaeological finds provide contradicting results, the previous statements by historians and Egyptologists regarding the division of the empire are largely in the range of hypotheses . The theory of division of empires is therefore controversial and is not accepted by all Egyptologists and historians. Skeptics suspect whether the division of the empire was purely bureaucratic in nature , whether it only concerned the rank and function titles of officials and whether Peribsen had not ruled over all of Egypt after all.

Peribsen's grave is in Abydos near Umm el-Qaab . There were two grave steles and numerous clay seal fragments, as well as jugs and various art objects. The tomb was looted during the 1st Intermediate Period and repeatedly restored during the Middle Kingdom .

Archaeological site

Sites and grave complex |

Peribsen's serechname was imprinted on jar seals made of clay and Nile mud . The majority of them were excavated around 1900 in Peribsen's grave in Umm el-Qaab near Abydos and around 1970 on the island of Elephantine . A clay seal fragment comes from the mastaba K1 in Beit Khallaf . While some of the seals have been completely preserved and have retained their original, conical shape, the majority of the seals are only preserved in small fragments .

Peribsen's name also appears in numerous inscriptions on clay jugs and stone vessels made of alabaster , sandstone , siltstone , dark gneiss , red porphyry and dark slate . All of them come from Abydos. The shapes of the vessels are varied, vases of cylindrical and amphora-like shapes have been excavated, as well as flat and high bowls. The inscriptions are preserved as black ink inscriptions , engraved , subsequently burned incisions and as raised reliefs.

Furthermore, around 1900 two large grave steles made of dark gray granite were discovered in front of the entrance to the grave. They are exhibited today in the British Museum in London and the Egyptian Museum in Cairo . Their shape is unusual, they look unfinished and rough. Some Egyptologists suspect that there could have been intent behind this type of design, but the associated symbolism remains unclear.

A cylindrical cylinder seal of unknown origin shows the name of Peribsen in a cartridge , together with the inscription Meri Netjeru ("Beloved of the Gods"). It is assumed that the cylinder seal, if genuine, must have come from a much later period, as royal cartouches only came into use with King Huni towards the end of the 3rd Dynasty . Another cylinder seal made of the same material shows Peribsen's name without a cartridge, but with the title Nisut-Biti ("King of Upper and Lower Egypt ").

About the name

Sethname instead of Horus name

Peribsen's name is unusual. According to ancient Egyptian tradition, when a king ascended the throne , he chose the falcon-headed god Horus as patron saint and regarded himself as his earthly representative. Since predynastic times this was mainly expressed by the name Horus . This consisted of a miniature representation of a stylized palace facade, the so-called Serech , on which the Horus falcon was enthroned. The king's name was written in a free window inside the serech. Peribsen, however, chose the god Seth instead of the deity Horus, who was just as popular in the early days and in the Old Kingdom . From around the First Intermediate Period , however, he was considered more and more with negative aspects until he was completely regarded as the God of Chaos and Evil from the Late Period . Many later rulers, especially from the New Kingdom onwards, showed a rather ambivalent or even negative attitude towards this deity in corresponding religious texts and defamatory representations of Seth . Some rulers, however, did the same to Peribsen and dedicated their birth name to Seth, as they claimed the warlike power ascribed to him for themselves. Prominent examples of this include Sutech ( 13th Dynasty ), Sethos I ( 19th Dynasty ), Sethos II (also 19th Dynasty) and Sethnacht ( 20th Dynasty ).

Ever since Peribsen's sethname has been known to research, there have been divergent views as to the reasons for the name change. The following is a discussion of the most important and most frequently cited theories.

Earlier theories

One of the best-known theories put forward by Egyptologists such as Percy E. Newberry , Walter Bryan Emery , Jaroslav Černý and Bernhard Grdseloff , is that there are power struggles among the priests of the Horus and Seth caste for influence on the Egyptian throne came. The thesis is supported by the observation that Peribsen's proper name does not appear in any later king list and that the tomb of Peribsen was destroyed and looted in antiquity. In addition, the grave stelae that once showed the animal of Seth above the royal serech had been scratched and rubbed off, with the obvious intention of making the Seth animal unrecognizable. Emery and Bernhard Grdseloff, who suspect a revolt of the priestly caste of Seth, have similar views. As an indication, they cite that many of the royal tombs of Abydos, including the tomb of Peribsen, fell victim to arson and looting. Emery and Černý also suspect that there were civil wars and economic grievances within the country under Peribsen, which occurred at the same time as Peribsen's name was changed. Because of this "political misfortune", Peribsen was banned from the royal records in addition to his rejection of a Horus name.

More recent findings

However, the current archaeological find so far only seems to prove that Peribsen is only recorded in Upper Egypt at the time, whereas in Lower Egypt, the north of Egypt, his name appears only once. For this reason, some of the research now assumes that Peribsen might not have ruled all of Egypt. An important piece of evidence, which, according to some Egyptologists, speaks against the theory of religious power struggles between two warring priests, is the false door in the mastaba tomb of the high official Scheri in Saqqara , who was in office during the early 4th dynasty . The door inscription gives the name of Peribsen and the name of another regent of the 2nd Dynasty, Sened , in one sentence. According to the inscription, Scheri was "Head of the Wab priests of Peribsen in the necropolis of Sened in his mortuary temple and at all other seats". This shows that at least until the 4th dynasty there was a comprehensive cult of the dead around Peribsen. In addition, Scheris Mastaba is located on Lower Egyptian ground ( Memphis ), not on Upper Egyptian (Thinis). Two colleagues and possible relatives of Scheri, Inkef and Sij , were also "Wab priests of Peribsen" and "Overseers of the Ka servants of Sened". Both contradict the assumption that Peribsen's public commitment to Seth was disapproved from the start and that his name was therefore removed from all records immediately after his death.

Jean Sainte Fare Garnot and Herman te Velde also point to the name of Peribsen, the translation of which provides indications that Peribsen must have continued to confess to Horus. His name translates as "Who comes out for their will", or "Both of your minds come out". The name syllable sn (“her / her / her”) is a plural spelling that clearly refers to two deities. As a result, there is no break with the traditional belief that an Egyptian ruler always embodied Horus and Seth at the same time. Such an ambiguity was not uncommon in early Egypt, the queens of the 1st Dynasty already bore the title " Who looks at Horus and Seth ". The name of Peribsen's successor, Horus-Seth Chasechemui , is also ambiguous. It means "the two mighty have appeared" and also refers to both imperial deities. In addition, Chasechemui had Horus and Seth placed together over his serech, where they are shown in a kissing pose. This was intended to express the reunification of Upper and Lower Egypt and the dual belief in rulers. Finally, Ludwig David Morenz and Wolfgang Helck draw attention to the fact that the targeted chiseling out of Seth animals has only been reliably proven since the New Kingdom . The eradication of Peribsen's patron saint on his grave stele can therefore not have taken place at the time. Dietrich Wildung also throws in that not only the royal cemetery of Abydos was plundered and set on fire, the necropolises of Naqada and Saqqara also fell victim to such devastation. An action directed against Peribsen personally can therefore be ruled out.

The clay seal inscriptions, which come from Abydos and Elephantine, show next to Seth the representations of the gods Asch , Min and Nechbet , who were worshiped during the reign of Peribsen. The fertility god Min has been worshiped since predynastic times, the goddess Nechbet appears under Peribsen for the first time in an anthropomorphic form. The Southern Shrine of el-Kab is often found at their feet . The desert and oasis god Asch, who was introduced from Libya, appears particularly often under Peribsen. It is so prominently highlighted in the inscriptions that Egyptologists such as Jean-Pierre Pätznick and Jochem Kahl are considering reading Peribsen's name as "Asch-Peribsen". However, this theory is not widely accepted. A vase made of red porphyry as well as several clay seal impressions show the representation of a sun disk over the Seth animal. The representations of the gods are seen as further evidence against a possible attempt to establish a new state religion.

In Egyptology today the view is held that Peribsen's empire was divided peacefully and nonviolently. Michael Rice , Francesco Tiradritti and Wolfgang Helck refer to the once magnificent and well-preserved mastaba graves in Saqqara, which belonged to high officials such as Ruaben , Nefersetech and a few others. They are all dated from the time of King Ninetjer to the end of the 2nd Dynasty under Chasechemui . The former splendor, high-quality architecture and their good state of preservation are, according to Egyptologists, signs that the nationwide cult of the dead for kings and nobles flourished continuously and was well organized. Such prosperity, which is to be expected for an extensive cult of the dead, would have been impossible in the event of economic grievances or civil war.

Today, Egyptology is generally distant from the theories of Emery, Newberry and Grdseloff, as they were based on the finds of their time, when there were only sparse finds next to the grave stelae and many of the clay seal impressions were neither published nor translated. The theses on changing the name of Peribsen may have been put forward prematurely and may therefore be incorrect.

identity

In the course of research, questions about his identity have arisen from Peribsen's name change. Walter Bryan Emery, Kathryn A. Bard and Flinders Petrie are convinced that Peribsen is identical to his successor, Sechemib-Perenmaat . They suspect that Sechemib changed his Horus name from "Hor-Sechemib" to "Seth-Peribsen" with the beginning of the division of the empire. They justify their explanation with the fact that, on the one hand, clay seals of the Sechemib were discovered in the necropolis of Peribsen and, on the other hand, Sechemib's own grave has so far not been found.

Hermann A. Schlögl , Wolfgang Helck, Peter Kaplony and Jochem Kahl, however, consider Sechemib and Peribsen to be two different people. They refer to the fact that said clay seals of the Sechemib were only found in the entrance area of Peribsen's grave, but never inside the burial chamber. They compare this find situation with that of King Hetepsechemui (founder of the 2nd dynasty), whose ivory labels were discovered in the entrance area of the tomb of King Qaa (one of the last or actually last rulers of the 1st dynasty ). Schlögl, Helck, Kaplony and Kahl conclude from the find situation at Sechemib that the latter had Peribsen buried.

Since Peribsen chose the deity Seth as patron saint, some Egyptologists suspect that Peribsen was a prince from Thinis or belonged to the Thinite royal family. The background to this assumption is the god Seth himself, who had his main place of worship in Naqada and, according to ancient Egyptian tradition, came from there. In this context, Darrell D. Baker suggested that Peribsen could have descended from a king of the 1st Dynasty .

Toby Wilkinson and Wolfgang Helck believe that Sechemib and Peribsen were related to each other. Their assumption is based on striking typographical and grammatical similarities in the inscriptions from Sechemib and Peribsen's time. In the vessel inscriptions of the Peribsen, for example, the frequent inscription Ini-Setjet (" Tribute payment of the inhabitants of Sethroë ") can be found, while Ini-Chasut ("Tribute payments of the desert nomads ") can be read repeatedly in the entries of the Sechemib . A further indication of a possible relationship between Peribsen and Sechemib are the real names of both rulers, who use the same name syllables "Per" and "Ib".

Wolfgang Helck and Dietrich Wildung consider it possible that Peribsen is identical to the Ramessid cartouche name Wadjenes . This explanation is based on the assumption that Peribsen's name was misinterpreted by the hieratic writing (the name was read out from improper writing). As an alternative, Wildung suggests Wadjenes as the direct successor to Ninetjer and thus as the predecessor of Peribsen.

The question of Peribsen's historical identity also gave rise to questions about his predecessors and successors. It is unclear whether Sechemib - unless he is identical with Peribsen - ruled before or after him. It is very similar with King Sened, he too can have been both predecessor and successor. The contradicting evidence makes any more precise, chronological classification of these three rulers difficult.

Reign

Due to the many possible interpretations that result from the sometimes contradicting finds, Egyptology regards the 2nd dynasty as particularly problematic. The background to this is the equally uncertain find situation regarding the change from 1st to 2nd dynasty. At the time of King Qaa's death, there appears to have been a quarrel over the throne, culminating in the looting of the royal cemetery at Abydos. The founder of the 2nd dynasty, King Hetepsechemui, moved his grave to Saqqara, his immediate successors, Nebre and Ninetjer, did the same. But Peribsen was evidently looking for a return to the earlier traditions and again chose Abydos in Upper Egypt as a burial place. One of his successors, Chasechemui, was also buried in Abydos. The reason for the return may have been the Thinitic origins of Peribsen and his successors, as well as the power that might have been restricted to the south.

Proponents of the theory of division of empires

Egyptologists and historians who are convinced of the division of the empire and dual rule during the 2nd dynasty continue to investigate the exact causes and circumstances that could have led to an empire division. Some researchers are certain that King Ninetjer , third ruler of the 2nd dynasty, divided the Egyptian empire into two independent empires and had two of his sons or selected heirs to the throne rule synchronously. They assume that by this time Egypt's administrative apparatus had become too large and complex and threatened to collapse. To prevent this and to facilitate the administration of the state, Egypt was divided and two rulers were installed at the same time.

However, it is unknown when exactly Egypt was divided into two independent halves. In this context, Percy E. Newberry points out that there may have been domestic political tensions under King Ninetjer. Newberry refers to the inscription on the Palermostein , a black basalt plaque that lists the names and annual entries of all rulers from the 1st Dynasty to the reign of King Neferirkare ( 6th Dynasty ) on the front and back . The Palermostein handed down the government years 7 to 21 for Ninetjer. In the 14th year of the reign, the ruler is said to have destroyed the cities of Shem-Re and Ha , if one of two possible interpretations applies . Dmitri B. Proussakov also throws in that from the 12th year of reign the ceremony "Appearance of the King" is no longer introduced with the full throne name (Nisut-biti) , but only referred to as the "Appearance of the King of Lower Egypt". Proussakov interprets this as an indication that Ninetjer only had limited power.

In contrast, Barbara Bell suspected a prolonged drought among Ninetjer that led to famine . In order to be able to secure the supply of the Egyptian population, the kingdom was divided until the drought and the associated famine ended. Bell justified her thesis with the records of the Nile flood heights below the annual window of the Palermostein. According to their interpretation, the Palermostein recorded unusually low levels of the Nile at the time of King Ninetjer. Today this theory has been refuted. Historians like Stephan Seidlmayer have recalculated and corrected Bell's estimates. Barbara Bell may not have considered that the Palermostein only shows the levels of the Nile in the region around Memphis and ignores the levels along the rest of the course of the Nile. Stephan Seidlmayer was able to prove that the Nile flood heights in Ninetjer's time were balanced and comparatively high. A drought as a reason for dividing the empire can therefore now be ruled out. The actual reason for a division of the empire remains unclear for the time being.

Opponent of the theory of division of empires

Not all Egyptologists share the assumption that Egypt is divided. Researchers like Winfried Barta , IES Edwards and T. Wilkinson draw attention to an increasing mention of Seth fetishes and shrines and bastions on the Cairo stone dedicated to that deity . In line IV of the Cairo stone C1 , in the annual fields assigned to King Ninetjer , the representations of the Seth beast are piling up. Seth animals also appear in his successor's annual fields. Accordingly, the influence of the Seth caste only increased gradually, not all of a sudden, as postulated for the beginning of the rule of Peribsen. Ninetjer's successor on the Cairo stone has not yet been unanimously identified, but recent investigations into the remains of the royal name bandarole reveal a four-legged animal above the Serech , according to Barta, Edwards and Wilkinson . The only early dynastic ruler to date to use a four-legged creature as the patron saint is King Peribsen. Wilkinson throws in, however, that the position of the name bandarole suggests a reign of about 10 or 12-14 years, which, however, appears strangely short in view of the extensive archaeological evidence. Since the researchers suspect that Peribsen might not have been the only ruler with a Seth animal as a serech figure, at least Barta and Edwards suggest various “problem rulers” such as Nubnefer , Weneg and Sened as possible Seth kings. Wilkinson, however, leans more towards Peribsen as his successor. The scholars exclude King Sechemib as a candidate, since he demonstrably and exclusively used the Horus falcon as Serech patron.

Furthermore, the scholars point out that the annals stone nowhere provides a clear indication that there were internal political conflicts or even a division of Egypt during the 2nd Dynasty. Therefore, they ask themselves whether the theory of a division of the empire in the sense of a division of the country into north and south, along with synchronous dual rule, is still tenable. The division into a southern and a northern half ultimately only affects the administrative titles of contemporary civil servants, not royal names, which merely indicates a purely bureaucratic innovation in the administrative system. To this end, they refer to numerous tone seals, which prove reforms with regard to the titles and functions of civil servants, which are now visibly aligned with the administrative reform sought by Peribsen: Under Peribsen, the meaning and reading of the high and important title Chetemti-bitj changed entertainingly, without the Spelling would have been changed. Instead of the usual reading and interpretation as "sealer of the king", the reading and interpretation to "sealer of the king of Lower Egypt" was expanded. This became necessary after the title Chetemti-shemau ("Seal of the King of Upper Egypt") was introduced under Peribsen and Sechemib . It is noteworthy that, instead of the expected override Chetemti-nesu the spelling Chetemti- schemau was chosen. The reason for this is obscure, but it could be based on the fact that Schemau ( Gardiner symbol M26 ) as heraldic coat of arms has always been more geographically associated with the term "Upper Egypt" than nesu (which is more closely associated with the term "King") was). The reason for the temporary introduction of the title Chetemti-schemau is now assumed to be a purely administrative necessity: economic bottlenecks and / or an administrative apparatus that has become too large may have been the reason for a formal division of office. Peribsen and Sechemib just wanted to restrict the power of officials and priests because they were becoming too influential. Ultimately, official titles such as that of the "royal sealer" had to be adapted to these innovations. After the formal division of the empire ended under King Chasechemui and the administrative system could again be managed by a single central office, the title “Chetemti-schemau” was given up again.

Political activities

Due to the archaeological finds, Peribsen's direct influence of power can only be proven for Upper Egypt. His empire only seems to have extended as far as Elephantine, where he founded a new administrative center called the White Treasury. His new royal residence, Chet-nubt ("Protection of Nubt"; Nubt was the Egyptian word for Naqada ) moved Peribsen to Ombos . Another frequently mentioned domain was called Iti-uiau ("Barken of the Lord"), important cities were Afnut ("Headscarf City"), Nebi ("Support City") and Hui-setjet ("Asian City"). Peribsen also founded important administrative houses such as Per-nubt ("House of Ombos") and Per-Medjed ("House of Meeting"), today's Oxyrhynchos . Inscriptions on stone vessels mention tribute payments by the inhabitants of Setjet (Sethroë), which could indicate that Peribsen founded a place of worship for Seth in the Nile Delta. However, this would presuppose that Peribsen either ruled over all of Egypt or at least was recognized as ruler by Lower Egypt.

The split in the administrative headquarters of Egypt ended with Chasechemui, where it was combined and reunified under the new central administration "House of the King" ( pr-nsw.t ; Per-nesut ). Since Peribsen a clear administrative hierarchy has been documented, which was successfully perfected under Chasechemui: the “House of the King” was subordinate to the “Supply Department” ( iz-ḏf3 ; Is-Djefa ) and the “Treasury” was subordinate to it. The hierarchy of the administrative departments is therefore as follows: House of the King → Supply Management → Treasure House → Manor → Vineyards → Individual Vineyard. In addition, various domains were subject to tax in the king's house, for example the domain " Seat of the harpooning Horus ". During the reign of Peribsen, the term of office of a high official, which is safely evidenced by a grave stele : Nefersetech ("Seth is gracious") may fall . This is suspected by the attribution of Seth, but is controversial.

On one of the clay seals found in Peribsen's grave, the first known grammatically complete sentence is recorded in hieroglyphics . The inscription reads: “The golden one / The one of Ombos presents the two countries to his son, the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Peribsen.” The salutation “The golden one” or “The one of Ombos” is the highest-ranking and most frequently used epithet of Seth. Under Peribsen, however, it was first used in writing.

Cultic and religious activities

As already mentioned, various deities were worshiped under Peribsen that were also worshiped under his predecessors. The numerous clay seals together with the images of the gods also name the places in which the cult centers of the respective gods were. The gods frequently mentioned and depicted include: Asch, Min, Nechbet , Horus, Seth, Bastet and Cherti . This speaks clearly against the attempt to introduce a one-god religion (monotheism). Furthermore, clay seals and vessel engravings show a sun disk above the set animal on the king's serech. It is unclear whether this was part of the royal name or only accompanied it. Under Peribsen's predecessors, the sun was still directly linked to Horus, the clearest expression of this religious association emerges in the Horus name of King Nebre. Under Peribsen the sun was linked to Seth, so there was always a direct reference to the supreme state deity. The arrangement on the inscriptions suggests that under Peribsen a religious change apparently took place and the sun moved more and more into the center of cultic veneration until it was elevated to an independent deity under the name Ra at the beginning of the 3rd dynasty . Towards the end of the reign of Chasechemui, the first personal names appear that make direct reference to the sun god.

Counter rulers

As already explained at the beginning, some researchers are convinced that Peribsen had to share the throne with other rulers. Since, in their opinion, the clay seal and vessel inscriptions seem to indicate that Peribsen and his successor, Sechemib-Perenmaat, ruled only in Upper Egypt, there is intensive research into who might have ruled Lower Egypt at that time. The Ramessid royal lists differ in their records after King Sened was named as the fifth regent of the 2nd dynasty. One reason for this may be that, for example, the King List of Saqqara and the Royal Papyrus Turin only reflect Memphite traditions, which is why only Memphite kings are mentioned. The list of kings of Abydos, however, is based on Thinitic traditions, which is why only Thinitic rulers are listed. Until King Sened is named, the king lists are in agreement, but after that the Saqqara list and the Turin Canon name three rulers as successors to Sened: Neferkare I , Neferkasokar and Hudjefa I. The Abydos list skips these kings and continues at Chasechemui, the last regent of the 2nd dynasty, under the pseudonym "Djadjai". According to some Egyptologists, the discrepancies between the king lists go back to the division of the empire during the 2nd dynasty.

Another problem are the many names of Horus and Nebtin that appear in inscriptions on stone vessels. These were discovered in the Great Western Gallery in the necropolis of King Djoser ( 3rd Dynasty ) in Saqqara . The inscriptions mention kings like Nubnefer , Sneferka , Weneg , Horus Ba and " Vogel ". Each of these kings is mentioned only once or a few times and the number of vessels that date from their lifetimes is strictly limited. Hence, Egyptologists and historians assume that these rulers only ruled for a very short time. King Sneferka may be identical to or a short-term successor to King Qaa. King Weneg-Nebti can perhaps be identified with the Ramessid cartouche name “Wadjenes”. But kings like Nubnefer, Ba and "Vogel" remain a mystery. Their names have so far only been discovered in Saqqara. Hermann A. Schlögl sees the successor of Peribsen in Sechemib and regards Neferkare I., Neferkasokar and Hudjefa I. as their counter-regents.

dig

Main grave

Peribsen was buried in Tomb P ("Grave P") of the royal cemetery of Umm el-Qaab near Abydos. The first archaeological excavations began in 1899 under the supervision and direction of the French archaeologist and Egyptologist Émile Amélineau . Further excavations took place under the British Sir Flinders Petrie around 1901. A third excavation was carried out by the Swiss philologist and Egyptologist Édouard Naville in 1910.

Compared to the graves of other rulers, the grave is of a much simpler construction and relatively small. The design model was probably the tomb of King Djer ( 1st Dynasty ), which has been regarded as the tomb of Osiris since the Middle Kingdom . The architecture of the outlines of the grave elements is based on a residential building. Mud bricks , thatch and some wood were used as building materials . The monument consists of two rectangular, nested enclosing walls with a central king chamber, the entire grave masonry is 2.90 meters high. The first, outer enclosure measures about 18 × 15 meters, the inner enclosure about 13 × 9.85 meters. The main burial chamber has the dimensions 7.8 × 4.15 meters and stands as a free construction in the center of the complex: a circumferential passage has been left free around the chamber. Between the grave entrance and the main chamber there is an anteroom, which is divided into two rooms by a passage, each of these rooms contains four storage magazines.

Follow-up examinations during a total of three excavation campaigns by the German Archaeological Institute Cairo (DAIK) between 2001 and 2004 showed that Peribsen's grave - in contrast to the other royal tombs of Umm el-Qaab - was completed in just one construction phase and only very carelessly plastered . Apparently the construction work was in a great hurry. The grossly negligent construction meant that the grave monument sank several times. The grave complex had already been devastated and looted by grave robbers in antiquity, during the annual pilgrimages to Umm el-Qaab in the course of the worship of Osiris it was poorly restored and some sacrificial vessels were left behind.

Special finds

Among the grave goods were, in addition to the already mentioned offerings from later times, some stone vases and bowls as well as earthen jugs, which can be safely assigned to Peribsen's era. Some stone vessels have edges coated with copper . Furthermore, copper tools and bracelet fragments made of flint and limestone were discovered, as well as pearls made of faience and carnelian . In addition, several vessels with the names of Peribsen's predecessors Ninetjer and Nebre were found. Special finds are a silver needle with the name of King Hor-Aha and several clay seal fragments with the name of the Sechemib . A black slate palette and a bony arrowhead originally come from Djer's grave. A stone vessel fragment bearing Peribsen's name was discovered in Queen Meritneith's tomb , but it is believed that the shard was carried there by Amélineau during the excavation work. At one time two large granite steles stood in front of the grave entrance , the design of which differs strikingly from that of the other royal tombs. Today they are in various museums.

Enclosure

The royal enclosure or cult area was located about a kilometer from the Peribsen burial site. Clay seals with the real name of Peribsen were found in the area of the east entrance and inside a destroyed sacrificial shrine. Therefore, the cult district is awarded to King Peribsen. It is known today under the English name Middle Fort ("Middle Fort"). First excavations began in 1904 under the supervision and direction of the Canadian archaeologist Charles Trick Currelly and the British Egyptologist Edward Russell Ayrton . The enclosure wall of the complex was excavated near the enclosure of King Chasechemui, known as Shunet El-Zebib ("Raisin Barn"). The perimeter of the cult area of Peribsen is 108 × 55 meters, the complex has three entrances: in the south, in the west and in the east. In the interior of the district there were only a few cult buildings, including a 12.3 × 9.5 meter sacrificial shrine. It was located on the south-east corner and once contained three small chapels. Additional burials were not discovered either at Peribsen's main grave or in the enclosure.

The tradition of burying his family and court at the same time as a king died was abandoned with the death of King Qaa towards the end of the 1st Dynasty . Since King Hetepsechemui no more secondary burials have been recorded.

literature

General literature

- Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Vol. 1: Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty (3300-1069 BC). Bannerstone Press, London 2008, ISBN 0-9774094-4-9 , pp. 362-365.

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Handbook of the Egyptian king names (= Munich Egyptological studies. Vol. 49). 2nd improved and enlarged edition. von Zabern, Mainz 1999, ISBN 3-8053-2591-6 , pp. 44-45.

- Michael Rice: Who's Who in Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London et al. 2001, ISBN 0-415-15449-9 , pp. 72, 134 & 172.

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , p. 195.

Special literature

- Laurel Bestock: The development of royal funerary cult at Abydos. Two funerary enclosures from the reign of Aha Harrassowitz (= Menes. Vol. 6). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-447-05838-4 .

- Susanne Bickel: The connection between the worldview and the state: Aspects of politics and religion in Egypt. In: Reinhard Gregor Kratz , Hermann Spieckermann (Ed.): Images of Gods, Images of God, Images of the World. Polytheism and Monotheism in the Ancient World. Volume 1: Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine (= research on the Old Testament. 2nd row, Vol. 17). Mohr Siebeck, Ulmen 2006, ISBN 3-16-148673-0 , pp. 79-99.

- IES Edwards (ed.): Early history of the middle east (= The Cambridge ancient history. Vol. 1-2). 2 volumes = 3 parts. 3rd edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1970, ISBN 0-521-07791-5 .

- Walter B. Emery : Egypt. Fourier, Wiesbaden 1964, ISBN 3-921695-39-2 .

- Nicolas Grimal : A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley & Blackwell, Oxford (UK) 1994, ISBN 0-631-19396-0 .

- Wolfgang Helck : Investigations on the thinite period (= Egyptological treatises. Vol. 45). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1987, ISBN 3-447-02677-4 .

- Wolfgang Helck: Investigations into Manetho and the Egyptian king lists (= investigations into the history and antiquity of Egypt , vol. 18). Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1956

- Erik Hornung : The One and the Many. Egyptian ideas of God. 2nd unchanged edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1973, ISBN 3-534-05051-7 .

- Jochem Kahl : Inscriptional Evidence for the Relative Chronology of Dyns. 0-2. In: Erik Hornung , Rolf Krauss , David A. Warburton (eds.): Ancient Egyptian Chronology (= Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1: The Near and Middle East. Vol. 83). Brill, Leiden et al. 2006, ISBN 90-04-11385-1 , pp. 94-115 ( online ).

- Jochem Kahl: "Ra is my Lord". Searching for the rise of the Sun God at the dawn of Egyptian history (= Menes. Vol. 1). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-447-05540-6 .

- Jochem Kahl, Markus Bretschneider, Barbara Kneissler: Early Egyptian Dictionary, Part 1 . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2002, ISBN 3-447-04594-9 .

- Peter Kaplony : The inscriptions of the early Egyptian period Volume 3 (= Ägyptologische Abhandlungen. Vol. 8, 3, ISSN 1614-6379 ). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1963.

- Peter Kaplony: "He is a favorite of women" - a "new" king and a new theory about the crown prince and the goddesses of the state (crown goddesses) of the 1st / 2nd. Dynasty. In: Egypt and Levant. Vol. 13, 2006, ISSN 1015-5104 , pp. 107-126, doi: 10.1553 / AE and L13 .

- PE Newberry : The Seth rebellion of the 2nd Dynasty. In: Ancient Egypt. No. 7, 1922, ZDB -ID 216160-6 , pp. 40-46.

- Jean-Pierre Pätznick: The seal unrolling and cylinder seals of the city of Elephantine in the 3rd millennium BC. Securing evidence of an archaeological artifact (= BAR, International Series. Bd. 1339). Archaeopress, Oxford 2005, ISBN 1-84171-685-5 (also: Heidelberg, Univ., Diss., 1999).

- William Matthew Flinders Petrie : The Royal Tombs of the first dynasty: 1900. Part 1 (= Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. Volume 18). Egypt Exploration Fund et al., London 1900, ( digitization ).

- William Matthew Flinders Petrie: The Royal tombs of the earliest dynasties: 1901. Part II (= Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. Volume 21). Egypt Exploration Fund et al., London 1901 ( digitization ).

- Dmitri B. Proussakov: Early Dynastic Egypt: A socio-environmental / anthropological hypothesis of “Unification”. In: Leonid E. Grinin (Ed.): The early state, its alternatives and analogues. Uchitel Publishing House, Volgograd 2004, ISBN 5-7057-0547-6 , pp. 139-180.

- Gay Robins: The art of ancient Egypt. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 1997, ISBN 0-674-04660-9 .

- Anna Maria Donadoni Roveri, Francesco Tiradritti (ed.): Kemet. All Sorgenti Del Tempo. Electa, Milano 1998, ISBN 88-435-6042-5 .

- Hermann A. Schlögl : Ancient Egypt. History and culture from the early days to Cleopatra. Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54988-8 .

- Christian E. Schulz: Writing implements and scribes in the 0th to 3rd dynasty. Grin, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-638-63909-5 .

- Stephan Seidlmayer : Historic and modern Nile stands. Investigations into the level readings of the Nile from the earliest times to the present (= Achet - Schriften zur Ägyptologie. Vol. A, 1). Achet-Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-9803730-8-8 .

- Alan J. Spencer: Early Egypt. The rise of civilization in the Nile Valley. British Museum Press, London 1993, ISBN 0-7141-0974-6 .

- Herman te Velde: Seth, God of Confusion. A study of his role in Egyptian mythology and religion (= Problems of Egyptology. Vol. 6). Reprint with come corrections. Brill, Leiden 1977, ISBN 90-04-05402-2 (also: Groningen, Univ., Diss., 1967).

- Dietrich Wildung : The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Volume 1: Posthumous sources on the kings of the first four dynasties (= Munich Egyptological studies. Vol. 17, ZDB -ID 500317-9 ). B. Hessling, Berlin 1969 (at the same time: Diss., Univ. Munich).

- Toby AH Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. Strategies, Society and Security. Routledge, London et al. 1999, ISBN 0-415-18633-1 .

- Toby AH Wilkinson: The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. The history of a civilization from 3000 BC to Cleopatra. Bloomsbury, London et al. 2011, ISBN 978-1-4088-1002-6 .

Web links

- Peribsen on Digital Egypt (English)

- Peribsen with Francesco Raffaele (English)

- The Ancient Egypt Site (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Jürgen von Beckerath: Handbook of the Egyptian king names. 2nd improved and enlarged edition. von Zabern, Mainz 1999, pp. 44-45.

- ↑ Flinders Petrie: The Royal Tombs of the earliest dynasties: 1901. Part II . London 1901, p. 26, section 11 ( digitized ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999.

- ↑ a b c d e P. E. Newberry: The Seth rebellion of the 2nd Dynasty. 1922, pp. 40-46.

- ↑ a b Herman te Velde: Seth, God of Confusion. 1977, pp. 109-111.

- ↑ a b Dietrich Wildung: The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Volume 1. 1969, p. 47 ff.

- ^ A b c Toby AH Wilkinson: Royal annals of ancient Egypt . Pp. 200-206.

- ↑ a b c d e Günter Dreyer and others: Umm el-Qaab - follow-up examinations in the early royal cemetery (16th / 17th / 18th preliminary report). In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK). Vol. 62, 2006, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 75-77 & 106-110.

- ↑ a b c d e f William Matthew Flinders Petrie , Francis Llewellyn Griffith : The royal tombs of the earliest dynasties: 1901. Part II. London 1901 ( Plate XXII, Fig. 178-179 ), (complete article as PDF file ).

- ↑ a b c Jeffrey A. Spencer: Early Egypt. 1993, pp. 67-72 & 84.

- ↑ a b c d e Anna Maria D. Roveri, F. Tiradritti: Kemet. Milano 1998, pp. 80-85.

- ↑ Peter Kaplony: The cylinder seals of the Old Kingdom. Volume 2: Catalog of the cylinder seals (= Monumenta Aegyptiaca. 3, ISSN 0077-1376 ). Part A: Text. Fondation égyptologique Reine Elisabeth, Brussels 1981, p. 13; Part B: panels. ibid 1981, plate 1.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999, pp. 199-201.

- ↑ Laurel be stock: The development of royal funerary cult at Abydos. 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999, p. 296.

- ^ Walter B. Emery: Egypt. 1964, pp. 105-106.

- ^ Thomas Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. 2002, pp. 219, 228 & 231.

- ↑ a b c d e Walter B. Emery: Egypt. 1964, pp. 105-108.

- ↑ a b c Jaroslav Černý : Ancient Egyptian religion. Hutchinson's University Library, London a. a 1952, pp. 32-48, online .

- ^ A b Bernhard Grdseloff: Notes d'épigraphie archaïque. In: Annales du service des antiquités de l'Égypte. Vol. 44, 1944, ISSN 1687-1510 , pp. 279-306.

- ↑ a b c d Ludwig D. Morenz : Syncretism or ideology-soaked word and writing game? The connection of the god Seth with the sun hieroglyph at Per-ib-sen. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. Vol. 134, 2007, ISSN 0044-216X , pp. 151-156, here pp. 154ff.

- ^ Gay Robins: The art of ancient Egypt. 1997, pp. 36-38.

- ↑ Peter Kaplony: Inscriptions of the early Egyptian times. 1963, plate IX, obj. 27.

- ↑ a b c d e Nicolas Grimal: A History of Ancient Egypt. 1994, pp. 55-56.

- ↑ a b c Werner Kaiser : On the naming of Sened and Peribsen in Saqqara B3. In: Göttinger Miscellen . (GM). No. 122, 1991, ISSN 0344-385X , pp. 49-55.

- ↑ a b Auguste Mariette : Les Mastabas de l'Ancien Empire. Fragment du dernier ouvrage. Publié d'apres le manuscrit de l'auteur par Gaston Maspero . F. Vieweg, Paris 1889, pp. 92-94, online .

- ↑ a b c Dietrich Wildung: The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Volume 1. 1969, pp. 45-47.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: Investigations on the thinite age. 1987, p. 118.

- ^ Jean Sainte Fare Garnot: Sur quelques noms royaux des seconde et troisième dynasties ègyptiennes. In: Bulletin de l'Institut d'Égypte. Vol. 37, 1, 1956, ISSN 0366-4228 , pp. 317-328.

- ^ Herman te Velde: Seth, God of Confusion. 1977, pp. 72-74.

- ↑ a b c d e Hermann A. Schlögl: The old Egypt. Munich 2006, p. 78.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Pätznick: The seal unrolling and cylinder seals of the city of Elephantine in the 3rd millennium BC. 2005, pp. 63-64.

- ↑ Erik Hornung: The One and the Many. 2nd unchanged edition. 1973, pp. 101-102.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999, pp. 282-283.

- ↑ Günther Dreyer, Werner Kaiser and others: City and Temple of Elephantine - 25th / 26th / 27th excavation report. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department (MDAIK). Vol. 55, 1999, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 172-174.

- ↑ Jochem Kahl: Ra is my Lord. Wiesbaden 2007, pp. 43-47.

- ↑ Peter Kaplony: The inscriptions of the early Egyptian times. Volume 3. 1963, p. 19 & plate 77.

- ^ Michael Rice: Who's Who in Ancient Egypt. 2001, pp. 72, 134 & 172.

- ↑ a b W. Helck: The dating of the vessel inscriptions from the Djoser pyramid. In: Journal of Egyptian Language and Antiquity. (ZÄS). Vol. 106, 1979, ISSN 0044-216X , pp. 120-132, here p. 132

- ^ Kathryn A. Bard: The Emergence of the Egyptian State. In: Ian Shaw (Ed.): The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, Oxford et al. 2000, ISBN 0-19-280293-3 , pp. 61-88, here p. 86.

- ↑ WM Flinders Petrie: The royal tombs of the earliest dynasties: 1901. Part II. London 1901 ( digitization ), pp. 7, 14, 19, 20 & 48.

- ↑ a b c d Wolfgang Helck: Investigations on the thinite age. Wiesbaden 1987, pp. 103-111 and p. 215.

- ↑ a b Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Volume 1. 2008, pp. 362-364.

- ^ Siegfried Schott : Altägyptische Festdaten (= Academy of Sciences and Literature, Mainz. Treatises of the humanities and social science class. Born 1950, No. 10, ISSN 0002-2977 ). Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz 1950, p. 55.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: Investigations into Manetho and the Egyptian king lists. 1956, pp. 13-14.

- ^ Walter Bryan Emery: Great tombs of the First Dynasty ( Excavations at Saqqara. Vol. 3). Government Press, London 1958, pp. 28-31.

- ↑ Peter Kaplony: "He is a favorite of women". 2006, pp. 126-127.

- ^ Toby AH Wilkinson: The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. 2011, pp. 64-65.

- ↑ Dmitri B. Proussakov: Early Dynastic Egypt. Volgograd 2004, p. 156ff.

- ↑ Barbara Bell: The Oldest Records of the Nile Floods. In: Geographical Journal. Vol. 136, No. 4, 1970, ISSN 0016-7398 , pp. 569-573.

- ↑ Hans Goedike: King Ḥwḏf3? In: Journal of Egypt Archeology. Vol. 42, 1956, ISSN 0307-5133 , pp. 50-53.

- ↑ Stephan Seidlmayer: Historic and modern Nile stands. 2001, pp. 87-89.

- ^ A b Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999, pp. 130-132 and 147.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Pätznick: The seal impressions and cylinder seals of the city of Elephantine in the 3rd millennium BC. Securing evidence of an archaeological artifact (= Breasted, Ancient Records. [BAR] International Series. Bd. 1339). Archaeopress, Oxford 2005, ISBN 1-84171-685-5 , pp. 211-213; see also: Jean-Pierre Pätznick: City and Temple of Elephantine - 25th / 26th / 27th excavation report. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK). Vol. 55, Berlin 1999, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 90-92.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Pätznick: The seal impressions and cylinder seals of the city of Elephantine in the 3rd millennium BC. Chr. Pp. 211-213; see also: Jean-Pierre Pätznick in: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Ägyptologische Institut Cairo . No. 55, German Archaeological Institute, Orient Department (ed.). de Gruyter, Berlin 1999, pp. 90-92.

- ^ Christian E. Schulz: Writing implements and scribes in the 0th to 3rd dynasty. Pp. 9-15.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Pätznick: The seal unrolling and cylinder seals of the city of Elephantine in the 3rd millennium BC. 2005, pp. 64-66.

- ↑ Jochem Kahl, Markus Bretschneider, Barbara Kneissler: Early Egyptian Dictionary, Part 1. Wiesbaden 2002, p. 107.

- ^ Eva-Maria Engel: New finds from old excavations - vessel closures from grave P in Umm el-Qa'ab in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. In: Gerald Moers et al. (Ed.): Jn.t dr.w. Festschrift for Friedrich Junge . Volume 1. Seminar for Egyptology and Coptic Studies, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 3-00-018329-9 , pp. 179–188, here pp. 181, 183–184.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999, pp. 89-91.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck, Eberhard Otto: Lexicon of Egyptology: Megiddo-Pyramiden -1982. -XXXII p . - 1272 col . (= Lexicon of Egyptology. Volume 4). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1982, ISBN 3-447-02262-0 , p. 326.

- ^ A b Christian E. Schulz: Writing implements and scribes in the 0th to 3rd dynasty. 2007, pp. 9-15.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999, pp. 75-76 & 89-91.

- ↑ Peter Kaplony: The inscriptions of the early Egyptian times. Volume 3. 1963, pp. 406-411.

- ↑ Jean-Phillip Lauer: La Pyramide à Degrés. Volume 4: Inscriptions gravées sur les vases. Fasc. 1-2. Institut français d'archéologie orientale, Cairo 1959, objects 104–109.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. P. 295.

- ↑ Jochem Kahl, Markus Bretschneider, Barbara Kneissler: Early Egyptian Dictionary, Part 1. Wiesbaden 2002, p. 234.

- ↑ Susanne Bickel: The combination of worldview and state image. 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Jochem Kahl , Nicole Kloth, Ursula Zimmermann: The inscriptions of the 3rd dynasty. An inventory (= Egyptological treatises. Volume 56). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1995, ISBN 3-447-03733-4 , p. 368.

- ^ IES Edwards: The Cambridge ancient history. 1970, pp. 31-32.

- ↑ Jochem Kahl: Ra is my Lord. Wiesbaden 2007, pp. 2–7 & 14.

- ↑ Günther Dreyer, Werner Kaiser and others: City and Temple of Elephantine - 25th / 26th / 27th excavation report. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department (MDAIK) . Vol. 55, 1999, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 172-174.

- ↑ see: Jean-Phillip Lauer: La Pyramide à Degrés. Tome 4: Inscriptions gravées on the vases. Fasc. 1-2. Institut français d'archéologie orientale, Cairo 1959, obj. 104.

- ^ A b Nicolas Grimal: A History of Ancient Egypt. 1994, p. 55.

- ^ Walter B. Emery: Egypt. 1994, p. 19.

- ↑ Peter Kaplony: A building named “Menti-Ankh”. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK). Vol. 20, 1965, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 1-46.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999, p. 82.

- ↑ Jochem Kahl: Ra is my Lord. Wiesbaden 2007, pp. 12-14.

- ↑ Émile Amélineau: Mission Amélineau. Tome 4: Les nouvelles fouilles d'Abydos 1897–1898. Compte rendu in extenso des fouilles, description des monuments et objets découverts. Partie 2. Leroux, Paris 1905, pp. 676–679.

- ^ Èdouard Naville: The cemeteries of Abydos. Part 1: 1909-1910. The mixed cemetery and Umm El-Ga'ab (= Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. Vol. 33, ISSN 0307-5109 ). Egypt Exploration Fund et al., London 1914, pp. 21-25 & 35-39.

- ↑ a b Laurel be stock: The Early Dynastic Funerary Enclosures of Abydos. In: Archéo-Nile. Vol. 18, 2008, ISSN 1161-0492 , pp. 42-59, here pp. 56-57.

- ↑ a b Laurel Bestock: The development of royal funerary cult at Abydos. 2009, pp. 47-48.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999, p. 281.

- ^ Walter B. Emery: Egypt. 1994, pp. 100 & 163.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

|

Sened ? Sechemib ? |

King of Egypt 2nd Dynasty |

Sened ? Sechemib ? |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Peribs |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Per-ib-sen (sethname) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Egyptian king of the 2nd dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 28th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 28th century BC Chr. |