Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (born May 13, 1842 in London ; † November 22, 1900 ibid) was a British composer , musicologist , organist and conductor . He is best known in the Anglo-Saxon-speaking world as a composer of light comic operas.

Life

Through his father, the military bandmaster and music teacher Thomas Sullivan (1805–1866), Sullivan came into contact with music from an early age. He made his first attempts at composition such as the 'Anthem By the Waters of Babylon' in 1850. At the age of twelve, Sullivan became a member of the Chapel Royal in London, where he received formative influences from 1854 to 1856. Thanks to his good voice, he became the “first boy” of the choir and came into contact for the first time with well-known artists, high society and the royal family through many appearances. Arthur Sullivan continued his musical education from 1856 at the Royal Academy of Music in London, including with John Goss .

His teachers recognized his talent and encouraged him to compose; some choral pieces were also performed. As the youngest participant, Sullivan won the Mendelssohn Competition, which was advertised for the first time in 1856, which, after two further years of training at the Royal Academy of Music, enabled him to study at the Leipzig Conservatory from 1858 to 1861 (among others with Robert Papperitz , Ignaz Moscheles and Carl Reinecke ). It was there that Sullivan, who was also a highly regarded pianist and conductor, decided to devote himself primarily to composing. Leipzig's cultural life offered a variety of stimuli; Among other things, Sullivan met Franz Liszt , who invited him in December 1858 to the world premiere of Peter Cornelius ' The Barber of Baghdad in Weimar.

After his successful completion in 1861, the London performance of his incidental music for William Shakespeare's The Tempest ( The Tempest ) in April 1862 catapulted Sullivan into the forefront of English composers. Sullivan established himself as a composer of orchestral and vocal works, with him organist and choir director positions at St. Michael's Church in Chester Square in London (1861-1867) and at St. Peter's Church in Kensington (1867-1872) a regular income procured. Among the commissioned works for major music festivals in the country 'The Prodigal Son' belonged ( The Prodigal Son ) for the " Three Choirs Festival " in Worcester (1869) and Kenilworth (1864) and 'The Light of the World' for the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival (1873). In 1872 Sullivan wrote a large Te Deum for the recovery of the seriously ill Prince of Wales . Numerous song compositions and chamber music shaped the early phase of Sullivan's career. His orchestral works, such as the concert overtures In Memoriam (1866), Marmion (1867, based on Walter Scott ) or the Di-ballo overture (1870), as well as his stage music for Shakespearean dramas also attracted attention . Sullivan also composed a cello concerto and a symphony in E major (“Irish”), which were enthusiastically received by the press and public in 1866.

In order to promote young English talent, Sullivan founded the National Training School for Music in 1876, which he headed until 1881, before the institute was integrated into the Royal College of Music in 1882 . Sullivan used his popularity for cultural-political engagement for the maintenance of the musical life. He received an honorary doctorate from Cambridge University and an honorary doctorate from Oxford University in 1879 .

Sullivan was the conductor of the Philharmonic Society from 1885 to 1888, and from 1881 to 1898 he was the artistic director of the Leeds Music Festival, where he familiarized the audience not only with the classics but also with the works of English colleagues and with contemporary music. As a conductor, Sullivan was one of the earliest advocates of historically informed performance practice. Due to his increased standard of living and his contacts with high society and the royal family, Sullivan needed a substantial source of income that only entertainment theater could provide, but not music education and the composing of oratorios and symphonies. The first work for the stage, the ballet L'Ile enchanteé (1864), was soon followed by early attempts in the field of comic opera with the one-act act Cox and Box (1866) and the two-act opera The Contrabandista (1867).

Gilbert and Sullivan

But only the collaboration with the playwright William Schwenck Gilbert led to artistically demanding results. Finally, the impresario Richard D'Oyly Carte (1844–1901) succeeded in putting the cooperation between the two on a solid foundation. Carte, offspring of a French-English family, initially worked as an employee at the instrument manufacturer Rudall, Carte & Co., but soon founded his own artist and concert agency. In 1870, Carte became manager at the Royalty Theater in Soho , which was financed by the singer Selina Dolaro, who wanted to shine there in the latest French Opéras bouffes (= comic opera). Meanwhile, Carte had plans to establish a national English (comic) opera in its own theater. Sullivan and Gilbert's first work for carte, the one-act opera Trial by Jury (1875), was a resounding success. Carte founded the "Comedy Opera Company Ltd." at the end of 1876 and became the manager of the Opéra Comique , a small theater in London's " Strand " theater mile . A new chapter in London's theater history began here in November 1877 with the “Entirely New and Original Modern Comic Opera” The Sorcerer . This opera was Sullivan's first success with a more extensive work for the stage, and the basic patterns of the following operas in terms of roles and orchestras emerged.

The financial gains made with the plays by Sullivan and Gilbert made it possible for Carte to break away from the backers of the old opera company and to found the "D'Oyly Carte Opera Company" on August 4, 1879. After all, Carte could even afford to build its own theater. The London Savoy Theater opened on October 10, 1881 as one of the most technically advanced houses of its time with the takeover of the opera Patience (1881) from the Opéra Comique. Sullivan was the driving artistic force that led theater veteran Gilbert to increase the quality of the plays. At the Savoy Theater, however, after Iolanthe (1882) and Princess Ida (1884) there were initial disagreements with Gilbert regarding the conception and design of the operas. Nevertheless, the duo's greatest triumph followed with the comic opera The Mikado (1885), which was followed by Ruddigore (1887), The Yeomen of the Guard (1888) and The Gondoliers (1889).

Sullivan's balancing act between theater, church and concert hall brought the composer into a conflict that shaped both his life and the reception of his works. Regardless of the audience success, Sullivan gradually had to get used to the criticism of wasting his talent on light music. Since English theaters did not offer any performance opportunities for serious operas by local composers, Sullivan - inspired by Hector Berlioz - wrote parallel dramatic cantatas such as The Martyr of Antioch (1880) and The Golden Legend (1886) for the Leeds Music Festival . For his cantatas, orchestral music and services to the English musical life, he received the accolade of Queen Victoria in May 1883 and was thus ' Knight Bachelor '.

Sullivan and Carte planned to establish historical-style opera alongside the national comic opera. For the planned great national opera, Carte had the Royal English Opera House (today's Palace Theater in London) built. The "romantic opera" Ivanhoe (1891) based on Walter Scott's novel remained on the program for a long time as a work of this kind, but there were no English repertoire works in this genre that could have ensured permanent performance. In 1890, after a dispute over financing issues (the so-called "Carpet Quarrel"), there was a break with Gilbert lasting several years, which was followed by the operas Utopia Limited (1893) and The Grand Duke (1896). During the last ten years of his life, Sullivan, who had chronic kidney disease, worked with various librettists. His most important late works include the operas Haddon Hall (1892), The Beauty Stone (1898) and The Rose of Persia (1899).

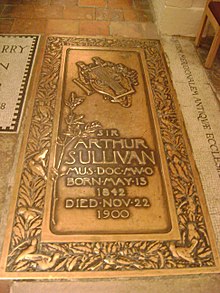

Sullivan died on November 22nd, 1900 and was buried in St Paul's Cathedral in London. The Sullivan Glacier on the West Antarctic Alexander I Island bears his name in his honor.

plant

As the most outstanding British musician of the 19th century, the internationally renowned Arthur Sullivan gave decisive new impulses to the musical life of his home country with his compositions and his commitment to cultural politics. With his operas, songs and choral works, he shaped the enthusiasm for music of subsequent generations and laid important foundations for the new heyday of English music at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Sullivan's comic operas are still part of the standard repertoire in the English-speaking world today. Although his dramatic cantatas are performed less often, they are essential links for the development of English choral music, from Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy's Elias to Edward Elgar's cantatas and William Walton's Belshazzar's Feast.

Sullivan's origins and training have had a lasting impact on his musical idiom. In addition to the idols of his youth ( Handel , Mozart and Mendelssohn ), inspiration came from contemporary compositional currents after his studies, primarily Robert Schumann , Franz Schubert , Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt . Much of Sullivan's concert and chamber music was based on their model. The friendship with Franz Liszt and Gioachino Rossini proved to be particularly beneficial for his work. Just like the successful Italian composer, Sullivan also worked in parallel on serious, dramatic works and comic operas, sometimes using the same design elements, for example the characterization of characters through different voices, such as the devil's demonic staccato commentaries on the pilgrims' choir in The Golden Legend and Dick Deadeye's staccato lines in the finale of Act 1 of HMS Pinafore (1878).

With the so-called "Savoy Operas" - a term after the parent company of the operas of Sullivan and Gilbert, which only later became a synonym for their works, but originally referred to all pieces premiered in the Savoy Theater - Sullivan established the archetypes of an opera in English Language and with operas like Ivanhoe created the only genre-typological new development on the English stages of the late 19th century. Between 1871 and 1896, Sullivan brought out 14 comic operas in cooperation with his librettist Gilbert, all of which were individual genre names such as "A Dramatic Cantata" (Trial by Jury) , "A Fairy Opera" (Iolanthe) , "An Entirely Original Supernatural Opera" (Ruddigore) , "New and Original Opera" (The Yeomen of the Guard) or "An Original Comic Opera" (Utopia Limited) . With these works, the notorious punch lines and critical failures of English literary and pictorial satire found their way into music theater, which targeted the strengths and weaknesses of the citizens of an up-and-coming, capitalist-oriented industrial and affluent society. The music-dialogue structure of Sullivan's comic operas goes back to models of an opera in the national language as found in Mozart ( Die Zauberflöte et al.) And Albert Lortzing ( Zar and Zimmermann et al.).

Sullivan himself pointed out that a serious undertone runs through his comic operas, which often brings a tragic-comic element into the conflict-ridden plot. Sullivan thereby sets an important counterpoint to Gilbert's sometimes exaggerated texts and plots. In critical crisis situations in human existence - such as in the finale of Act 1 and the quartet "When a wooer goes a-wooing" by The Yeomen of the Guard or the confrontation with the ancestors in Act 2 by Ruddigore - Sullivan intensifies the music psychological differentiation and dramatic intensity that are unparalleled in comic opera of the 19th century. For the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, Sullivan put together a high-quality, first-class ensemble that formed the basic line for all other productions from The Sorcerer (not just the operas with Gilbert): tenor and soprano as a lover, mezzo-soprano and baritone as another young woman along with Galan, a baritone as a comedian and bass and alto for an aging couple. Regardless of the constant basic requirements of the permanent ensemble, Sullivan succeeded in musically giving each piece and each figure an individual, unmistakable sound character. Avoiding clichés is essential: The keyword “Topsy-turvydom” (“wild mess, mess”) outlines the nonsense logic that is so characteristic of the plays by Sullivan and Gilbert, where the stage world is symbolically upside down the increasingly faster pace of life in a technical, externally determined, materialistically oriented world.

A special feature of Sullivan's comic operas is the disillusioning structure of the music. In many cases he composed against expectations: These include the exaggerated octave jump and the ironic melisms in the supposedly patriotic hymn "He is an Englishman" from HMS Pinafore or the tension-laden drama in the ghost scene from Ruddigore , which many - not least Gilbert - in one considered comic opera to be inappropriate. For him, the “opera of the future” that Sullivan had in mind represented a compromise between the German, Italian and French schools. And so in his comic pieces he parodied musky pathos and theatrical clichés, but also used different elements of Central European opera in a virtuoso manner, which seemed to him suitable for his stage works and oratorios in order to be able to adequately represent moods and emotions. In return, he wanted his librettists to provide humanly credible material, especially in the field of comic opera. His empathic, humanistic attitude is shown, for example, by setting the arias of the old maidens, often mercilessly mocked by Gilbert, such as in the sensitive cello solo in Lady Jane's "Sad is that woman's lot" (Patience) or in Katisha's aria (The Mikado) , in which stylistic elements of expressive lamentations are not used parodistically, but as an indicator of emotional state in life crises. In dramatic works like The Golden Legend , The Beauty Stone or Ivanhoe, Sullivan does not demonize the antagonists; for this he gives them individuality through rhythmic and melodic peculiarities, as well as an economical, individually used instrumentation, as in the aria of the Knights Templar “Woo thou thy snowflake” ( Ivanhoe , Act 2).

instrumentation

Sullivan's subtle handling of complicated metric structures (e.g. in “The sun whose rays” in The Mikado or “Were I thy bride” and “I have a song to sing, O” in The Yeomen of the Guard ) served as a model for the setting of English poetry. No less remarkable was his technical ability to achieve a great richness of sound with just a few instruments (e.g. in the overture to The Yeomen of the Guard ). Sullivan's way of composing is geared to the possibilities available to him: The Savoy Theater had an orchestra with 2 flutes, 1 oboe, 2 clarinets, 1 bassoon, 1 piccolo, 2 horns, 2 trombones, 2 cornets, 2 timpani, cymbals, small and large drums, triangles and strings (from The Yeomen of the Guard with 2 bassoons and 3 trombones). After intensive preparatory work, the score sometimes only took on its final shape during rehearsals, for example when the positioning of the singers on the stage required a more cautious orchestra. Sullivan had more extensive creative possibilities with operas such as Ivanhoe and dramatic cantatas such as The Golden Legend , for which it was also possible to use English horn , bass clarinet, double bassoon, tuba, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones and harp . Nevertheless, Sullivan uses large volumes of sound only very sparingly and dresses numbers and scenes in a characteristic sound robe both in the theater and in the concert hall (in a letter of March 12, 1889, Sullivan uses the phrase “clothed with music by me”). The main emphasis is less on the suggestive power of ever larger orchestral line-ups (a tendency that Sullivan refused, as he also took a critical stance towards Wagner), but on a classically oriented style pluralism: classic with regard to the transparent handling of the orchestral sound (himself with the large festival orchestras) and pluralistic in terms of the use of style elements that are appropriate for the sensitive musical characterization of figures and scenes through instrumental effects, timbres and rhythmic and melodic development.

Oratorios and songs

Alongside Alexander Mackenzie , Hubert Parry , Charles Villiers Stanford and Frederic Cowen, Sullivan is one of Great Britain's leading oratorio composers. The connection to music theater appears as a structural constant in his composing: the dramatic cantata on the biblical parable of the prodigal son The Prodigal Son already has operatic elements; The Martyr of Antioch , which was also staged, and Sullivan's main work The Golden Legend , are action-intensive cantatas with a pronounced dramatic gesture that are based on non-sacred material. With the dramatization of a medieval legend, Hartmann von Aue 's Poor Heinrich , Sullivan made the figure of Satan, who had been banned from English music literature for so long, acceptable again in The Golden Legend . Sullivan takes up suggestions from Berlioz's opus La damnation de Faust (1846), which he also performed himself, and Liszt's The Bells of the Strasbourg Minster (1874). What is striking about The Golden Legend , in addition to some bold harmonic twists, is the figure of Lucifer , who, as later in the opera The Beauty Stone , is no longer a goat-footed, horned monster, but appears now as a monk, now as a nobleman, and is musically multifaceted becomes.

Sullivan's well over a hundred song and choral movements were composed mainly in the 1860s at the beginning of his career, where they offered him good earning opportunities within the rapidly expanding music lover market. Sullivan mostly drew from the fundus of classical and romantic patterns, whereby the German-Austrian tradition of the art song was the model for his song creation, especially in the design of the piano part. Sullivan mostly chose sophisticated text templates. After early success with settings of Shakespeare texts - Orpheus with his lute (from Henry VIII ) is best known - he turned to the poems of Alfred Tennyson , Rudyard Kipling , Victor Hugo , Joseph von Eichendorff and George Eliot . Many of Sullivan's songs have a folksong-like tone, but he also repeatedly experimented with compositional design options that led to harmonic and melodic twists that were unusual for the time. Based on Schumann's love of poets, the song cycle The Window or The Songs of the Wrens (1871) based on texts by Tennyson was created. This is based on a precise key map; the eleven songs are characterized by an extended piano part and melodies whose German models are unmistakable. Sullivan's most popular song setting ever - 500,000 copies sold between 1877 and 1902 and the first song to be heard on phonographs in England - was The Lost Chord (text: Adelaide A. Procter).

Orchestral works

Sullivan's orchestral music clearly shows the influence of his training in Leipzig. The Symphony in E major (1866) already shows some of the most important characteristics of Sullivan's orchestral treatment. While the orchestral line-up is based on Schumann's symphonies , harmony, counterpoint and phrasing are stylistically influenced by Mendelssohn and Schubert. Even if numerous solo and duet passages can be found in the treatment of the woodwinds, as in Mendelssohn's, Sullivan does not imitate given patterns schematically, but always maintains a certain flexibility. The influence of Hector Berlioz , whose sacred works and Grand Symphonie funèbre et triomphale, as well as Sullivan's large commissioned works such as the Te Deum Festival (1872) and the Boer War Te Deum (premiered posthumously ) is particularly evident in his concert overtures, when using trombones and deep string instruments 1902), in which a military band is used, inspired. Also striking are instruments that were not common in German tradition. Until 1873 (in The Light of the World ) Sullivan used the ophicleide mainly in his concert overtures; In the Di ballo overture he combines the serpent with the trombones to form a quartet. If certain instruments are not available for the desired sound effects, Sullivan resorts to unusual solutions, for example by imitating a cor anglais in the symphony by notating the oboe parts one octave lower than the clarinets. In the stage music, too, there is a tendency to use massive duplications and opulent tutti effects sparingly; rather, flexible handling of changing orchestral voices leads to the greatest possible transparency. This, as well as the integration of national stylistic elements (folk songs, marches, sea shanties), paved the way for Elgar, whom he supported at the beginning of his career.

Arthur Sullivan and the English Opera

Sullivan's services to the English opera consist of establishing a national opera in his home country, whereby the achievements in the field of German opera by Carl Maria von Weber , Heinrich Marschner and Albert Lortzing , which he was able to experience in Leipzig, are a model for him possessed. The final impetus to write for the stage came when he met Gioachino Rossini , whom he met in late 1862 when he had traveled to Paris with Charles Dickens . “I think Rossini was the first person who wowed me with a love of the stage and everything related to opera,” Sullivan recalled. In collaboration with theater manager Richard D'Oyly Carte, Sullivan created a wide range of works for opera in English between 1875 and 1900. In doing so, he shaped the different archetypes of English music theater (cf. Eden / Saremba 2009) in an era in which other British composers - if they were concerned at all - still wrote operas on Italian libretti or had their stage compositions premiered in German theaters. Sullivan's most important librettist, William Schwenck Gilbert, primarily provided texts for comic operas with some current satirical references. Sullivan used the text templates for his differentiated musical design and subtle instrumentation. Sullivan's compositions, along with those by Henry Purcell and Benjamin Britten, are among the most outstanding settings of verse in the English language. For the stage, Sullivan created exemplary works in the field of fantastic-comic opera (Iolanthe 1882, Ruddigore 1886), social comedy (Trial by Jury 1875, Patience 1881) and lyrical-romantic opera (The Yeomen of the Guard 1888, The Beauty Stone 1898 with text book by Arthur W. Pinero). The exoticism popular at the time was served in The Mikado (1885, another collaboration with Gilbert) and The Rose of Persia (1899 with Basil Hood's textbook).

For his operatic work, Sullivan always strived to set "humanly charming and believable stories" and "to reinforce the emotional moment not only of the words, but above all of the situation" in his music. Gilbert was unable to follow Sullivan's and Carte's plans to establish a national opera in the local language. He recycled old ideas so often that Sullivan grew tired of what he called his "puppet show". Sullivan worked with Julian Sturgis and Sydney Grundy for projects with historical subjects such as Ivanhoe (1891) and Haddon Hall (1892), and Joseph Bennett wrote the textbook for the dramatic cantata The Golden Legend (1886 after Hartmann von Aues Der arme Heinrich ). After all, Sullivan was still able to wrest the libretto for the lyrical-romantic opera The Yeomen of the Guard from Gilbert in 1888, which the composer loved among his stage works.

Sullivan formulated his artistic principles as an opera composer in an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle in July 1885. “The opera of the future is a compromise,” he said, “because it doesn't come from the French school with its sumptuous, kitschy melodies, its gentle effects of light and shadow, its theatrical gestures full of showmanship; not from the Wagnerian school with its gloom and serious, ear-splitting arias, with its mysticism and its false feelings; and also not from the Italian school with its exaggerated arias, fioritures, and hair-pulling effects. It is a compromise between these three - a selection from the merits of the other three. "

Sullivan always made sure that his works were not performed in an edited form or defaced for marching bands, because "orchestral colors play such a big role in my work that it loses its appeal if they are taken from him". Even if the cultural establishment accused Sullivan while he was still alive that "a musician who has been knighted can hardly write department store ballads - he must not dare to get his hands dirty with anything less than an anthem or a madrigal" ( Musical Review, May 1883), he had no problems even with his multifaceted works, which he wrote in all genres. “If my works can make any claims as compositions, then I am counting completely on the serious undertone that runs through all of my operas,” says Sullivan. “When working out the scores, I stick to the principles of the art that I learned while working on heavier pieces. Any musician who analyzes the scores of these comical operas will not look in vain for this seriousness and seriousness. "

The influence of the so-called “English Musical Renaissance” movement (see Stradling / Hughes 1993) and the program policy of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company had a negative effect on reception. Sullivan's stage works were, reduced to the marketing label “Gilbert and Sullivan”, limited to the collaboration with Gilbert and copyright claims prevented Sullivan's operas from finding their way into the national opera ensembles that established themselves from the 1920s onwards, and opera in English was professional wanted to perform. Only after the copyright expired (50 years after Gilbert's death) was Sadler's Wells Opera able to add “Iolanthe” to its repertoire for the first time in 1962.

Others

In 1888 Thomas Edison sent his "Perfected Phonograph " to George Gouraud in London, and on August 14, 1888, Gouraud presented the device to London at a press conference. He also played a recording of a piece for piano and cornet from Sullivan's "The Lost Chord". This was or is one of the oldest music recordings ever made . A series of presentations followed during which the device was shown to members of society at "Little Menlo" in London. Sullivan was invited on October 5, 1888. After dinner he recorded a short speech on the device to send to Edison. In it he said among other things:

"I can only say that I am astonished and somewhat terrified at the result of this evening's experiments: astonished at the wonderful power you have developed, and terrified at the thought that so much hideous and bad music may be put on record forever. But all the same I think it is the most wonderful thing that I have ever experienced, and I congratulate you with all my heart on this wonderful discovery. "

These recordings were discovered in the Edison Library in New Jersey in the 1950s.

Quotes

"I believe that Rossini was the first to inspire me with a love of the stage and everything that has to do with opera."

“In England they have no idea of letting the orchestras play with the degree of fire and color gradation that they can do here in Germany, and that is exactly what I want to achieve: to make the English orchestras as perfect as those on the continent , and even more, because the strength and tone of ours is stronger than that of foreign ones. "

"The Meistersinger von Nürnberg is not only Wagner's masterpiece, but the greatest comic opera that has ever been written."

"If The Sorcerer is a success, it will be another nail in the coffin of the French Opéra bouffe."

“My dear Carte, I regret to inform you that when I went to the theater last Tuesday I discovered that the orchestra was very different from the one I used to rehearse Pinafore, both in terms of size and performance. Apparently two second violins were missing and the whole orchestra is of very different quality. I ask you to note that - if these shortcomings are not corrected by Saturday and the performance of the orchestra is not improved through the engagement of better instrumentalists with the woodwinds and strings, I will refuse the theater permission to perform my music on Monday evening . "

“I regret that my music is not performed the way I wrote it. Orchestra colors play such a big role in my work that it loses its appeal when they are taken from it. "

"If my works can make any claims for themselves as compositions, then I fully count on the serious undertone that runs through all my operas."

"I hereby authorize you to take all necessary steps to prevent the sale of these unapproved versions of my operas throughout Germany and, if necessary, to take legal action."

“The Lost Chord may not be performed as a hornpipe travesty at the guards barracks either today or any other evening. Otherwise I will unfortunately be forced to take legal action and claim damages. "

"Strokes, additions, changes, etc. - I was angry [...] Overall, very well. - The protagonists were all opera singers. "

“The power of music is something wonderful when, as in Zar and Zimmermann, with just a few simple notes that are put together properly, we succeed in making the most delicate strings in us sound and also making a tough guy like me soft to get."

Works (selection)

- The Tempest (incidental music; 1861/64)

- Kenilworth (Masque; 1865)

- Symphony in E major ("Irish") (1866).

- Cello Concerto (1866).

- Concert overture 'In Memoriam' (1866)

- Concert overture 'Marmion' (first performance on June 3, 1867)

- Cox and Box (Triumviretta in one act; Libretto: Francis C. Burnand; First performance: May 11, 1867 at the Adelphi Theater in London)

- The Long Day Closes (1868)

- The Prodigal Son (oratorio; 1869)

- Concert overture 'Di Ballo' (1870)

- Thespis (comic opera; 1871)

- The Merchant of Venice (incidental music; 1871)

- The Light of the World (oratorio; 1873)

- The Merry Wives of Windsor (incidental music; 1874)

- Trial by Jury (Komische Oper; 1875)

- The Sorcerer (comic opera; 1877)

- Henry VIII (incidental music; 1877)

- The Lost Chord (song; 1877)

- HMS Pinafore (comic opera in two acts; libretto: WS Gilbert; first performance on May 25, 1878 at the Opéra Comique, London)

- The Pirates of Penzance (comic opera; 1879)

- The Martyr of Antioch (Sacred Musical Drama; 1880)

- Patience or Bunthornes Bride (Komische Oper; 1881)

- Iolanthe (comic opera in two acts; libretto: WSGilbert; first performance on November 25, 1882 in the Savoy Theater, London)

- Princess Ida (comic opera; 1883)

- The Mikado (comic opera; 1885)

- The Golden Legend (oratorio; libretto: Joseph Bennett (based on Longfellow); first performance on October 16, 1886 in Leeds)

- Ruddigore (comic opera; 1887)

- The Yeomen of the Guard (comic opera; 1888)

- Macbeth (incidental music; first performance on December 29, 1888)

- The Gondoliers (comic opera; 1889)

- Ivanhoe (great opera in three acts; libretto: Julian Sturgis; world premiere on January 31, 1891 at the Royal English Opera, London)

- The Foresters (incidental music; 1892)

- Haddon Hall (An Original Light English Opera (in three acts); Libretto: Sydney Grundy; First performance on September 24, 1892 at the Savoy Theater, London)

- Imperial March (March for the opening of the "Imperial Institute"; first performance on May 1, 1893)

- Utopia Limited (comic opera in two acts; libretto: WS Gilbert; first performance on October 7, 1893 in the Savoy Theater, London)

- The Chieftain (comic opera in two acts; libretto: Francis C. Burnand; first performance on December 12, 1894 in the Savoy Theater, London)

- King Arthur (incidental music; 1895)

- The Grand Duke (comic opera in two acts; libretto: WS Gilbert; first performance on March 7, 1896 in the Savoy Theater, London)

- Victoria and Merrie England (ballet; scenario: Carlo Coppi; world premiere on May 25, 1897 at the Alhambra Theater, Leicester Square, London)

- The Beauty Stone (Romantic musical drama in three acts; first performed May 28, 1898 at the Savoy Theater, London)

- The Rose of Persia (comic opera; 1899)

- Te Deum laudamus (1902).

Literature (selection)

- Arthur Lawrence: Sir Arthur Sullivan: Life Story, Letters, and Reminiscences . Chicago / London 1899. (reprint: Haskell House Publishers, New York 1973)

- Percy M. Young: Sir Arthur Sullivan . London 1971, ISBN 0-460-03934-2 .

- Arthur Jacobs: Arthur Sullivan - A Victorian Musician . Aldershot 1992, ISBN 0-85967-905-5 .

- Robert Stradling, Meirion Hughes: The English Musical Renaissance 1860-1940 - Construction and Deconstruction . London / New York 1993, ISBN 0-415-03493-0 .

- Meinhard Saremba : Arthur Sullivan - A composer's life in Victorian England . Wilhelmshaven 1993, ISBN 3-7959-0640-7 .

- M. Saremba: Arthur Sullivan - The non-person of British music. In: Elgar, Britten & Co. A history of British music in twelve portraits. Zurich / St. Gallen 1994, ISBN 3-7265-6029-7 .

- Meinhard Saremba: In the Purgatory of Tradition: Arthur Sullivan and the English Musical Renaissance. In: Christa Brüstle, Guido Heldt (Hrsg.): Music as a Bridge - musical relations between England and Germany . Hildesheim 2005, ISBN 3-487-12962-0 .

- David Eden (Ed.): Sullivan's Ivanhoe . Saffron Walden 2007, ISBN 978-0-9557154-0-2 .

- Meinhard Saremba: A Broad Field - About Gioachino Rossini and Arthur Sullivan. In: Reto Müller (Ed.): La Gazzetta. (Journal of the German Rossini Society). 18th year, Leipziger Universitätsverlag 2008, pp. 25–39, ISSN 1430-9971 .

- David Eden: The non-person of English music. In: Sullivan Journal. (Magazine of the German Sullivan Society). No. 1, June 2009, pp. 29-45.

- D. Eden, M. Saremba (Eds.): The Cambridge Companion to Gilbert and Sullivan . Cambridge University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-71659-8 .

- Ulrich Tadday (Ed.): Arthur Sullivan. (= Music Concepts. Volume 151). edition text + kritik, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-86916-103-7 .

- Albert Gier , Meinhard Saremba, Benedict Taylor (Eds.): SullivanPerspektiven I - Arthur Sullivan's operas, cantatas, orchestral and sacred music Oldib-Verlag, Essen 2012, ISBN 978-3-939556-29-9 .

- Albert Gier , Meinhard Saremba, Benedict Taylor (eds.): SullivanPerspektiven II - Arthur Sullivan's stage works, oratorios, incidental music and songs Oldib-Verlag, Essen 2014, ISBN 978-3-939556-42-8 .

- Antje Tumat, Meinhard Saremba, Benedict Taylor (eds.): SullivanPerspektiven III - Arthur Sullivan's music theater, chamber music, choral and orchestral works, Oldib-Verlag, Essen 2017, ISBN 978-3-939556-58-9 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b "Historic Sullivan Recordings", ( Memento of October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) the Gilbert and Sullivan Archive

Web links

- Literature by and about Arthur Sullivan in the catalog of the German National Library

- Gilbert and Sullivan

- German Sullivan Society

- Sheet music and audio files by Sullivan in the International Music Score Library Project

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sullivan, Arthur |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Sullivan, Arthur Seymour (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British composer, musicologist, organist and conductor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 13, 1842 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 22, 1900 |

| Place of death | London |