Bürmooser Moor

The Bürmooser Moor is an approximately 74 hectare moor area in the municipality of Bürmoos in the north of the federal state of Salzburg , about 25 km north of the city of Salzburg . From the middle of the 19th century until 2000, peat was mined there, and the moor has been renatured since then. Together with the neighboring Weidmoos and the Upper Austrian Ibmer Moor, it forms the largest contiguous moorland in Austria with a total of around 2000 hectares. The Bürmooser Moor has been a nature reserve since December 2008 and is designated as a Natura 2000 protected area.

history

Names and ownership

→ For the name Bürmoos, see the corresponding section in the article Bürmoos .

The name for the moor was originally Biermoos ( etymologically going back to Birkmoos ; despite the different origins of the word , moss has been a variant of moor in terms of content since the Middle Ages, especially in place and field names ). Probably the first mention of the Biermoos moor can be found in a landscape description by Lorenz Hübner in 1796 . In the 19th century, when a human settlement developed in the area, the name was transferred to it, today's municipality of Bürmoos. For the moor itself, the affiliation designation Bürmooser Moor was created .

As earlier alternative names, Ziegelstadelmoos , Stierlingmoos and Bürmoor are mentioned. For the former, Schreiber (1913) assumes the fact that even before the full economic exploitation of the bog from the 1850s onwards, clay was extracted for the manufacture of bricks and consequently the name derives from the brickworks. Because allegedly one already spoke in writings from the time around 1800 of a Ziegelstadelmoos . Even later, Ziegelstadelmoos refers to the eastern part of the moor, where its economic use began.

The variant Stierlingmoos is derived from the location of Stierling (today in the south of Bürmoos). The name Stierling is already mentioned by Hübner and is also present in the Franzisceis cadastre , but the moor area there is only recorded as beer moss . The bullling forest still exists today , which can be seen in the cadastre as the southern boundary of the moor.

The moor or parts of it were named after the owners over time. Because going back to a decree of the Salzburg Archbishop Johann Ernst von Thun from 1700 that “... all Möser in the judicial districts in front of the mountains are to be described and to be made arable”, it was possible for private persons to buy moorland if they procured them accordingly . Actual reclamation in the sense of sustainable drainage did not gain momentum in many places until the beginning of the 19th century.

From 1852 the court and court advocate Johannes Gstirner from St. Johann im Pongau was one third of the ideal co-owner of the moor, which began with its development in the eastern part, the Ziegelstadelmoos. In 1862 there was a real division, and the reasons were written down to the individual owners. From then on the Ziegelstadelmoos was called Gstirnermoos . Another part in the south was owned by Heinrich von Mertens from Salzburg , the third part went to a German Count Lippe-Weißenfeld . In 1877 Gstirner sold his property to the lawyer and landowner Joseph von Meittinger, who also came from St. Johann, and he resold the property to the Leipzig lawyer Eugen Zehme in 1887 . The latter went back into the naming of the moor area. The settlement Zehmemoos that arose there is now a district of Bürmoos with this name . Von Meittinger is immortalized in a street name there.

Another name for part of the Bürmooser Moor was the name Wahamoor , which is used in the community to this day for a wetland west of Zehmemoos. It was named after Josef Waha, station master in Lamprechtshausen and, after Eugen Zehme, later owner of the brick factory in Zehmemoos. After Waha, the eastern part of the Bürmoos state road L115 is also named Wahastraße within the municipality of Bürmoos .

The westernmost part of today's moor protection area is also called Rodinger Moos or Rodinger Winkel , named after the village of Roding, which belongs to the municipality of Sankt Georgen near Salzburg .

Until the independent political municipality of Bürmoos was formed in 1967, the Bürmooser Moor lay on the municipal areas of Lamprechtshausen and Sankt Georgen near Salzburg.

Economical meaning

The reason for Count von Thun's decree on the use and exploitation of Salzburg's peat bogs was the fact that the private use of wood was drastically restricted in the 17th and 18th centuries, as the trees were needed for salt production in Hallein . However, it was not until around 1850 that the Bürmoos Moor began to be used on a large scale, when the peat extracted there became an interesting source of fuel for a glassworks. The yield of the Bürmoos moor together with the adjacent Weidmoos was given by Hübner as around 6,000 opencast mines . (1 open pit or daily work corresponded to around 8,200 sods .) The original extent of the Bürmoos Moor alone was 437 hectares, and 375 hectares are mentioned as a mineable area. For a long time, the peat was mined by hand, mechanically only from 1967 until it was discontinued in 2000, although Johannes Gstirner's attempts at machining were already in the 19th century.

One of the first industrial uses of the moor was the attempt to dig burnt peat and bring it to Vienna by water, but this ultimately failed due to the high freight costs. Heinrich von Mertens founded a tar factory in 1866, which went bankrupt in 1868. Lorenz von Stein bought the factory and the estate with the brickworks from the bankruptcy estate and in 1871 founded the “Salzburger Torfmoorgesellschaft” based in Vienna. The company began manufacturing glass in 1873, an industry that lasted until 1929. In 1879 the peat moor company went bankrupt and Alois Kupfer and his son-in-law Ignaz Glaser from Prague took over the glassworks.

From 1893 peat litter was also produced for the peasantry, trying to curb the procurement of forest litter for the cattle, as this often affected the forests. Like the peat, this was also brought to Laufen by carts until a railway line was built and from there transported on by water to the Salzach , Inn and Danube . However, the farmers hardly accepted the peat litter and the business was stopped after a while.

In the time of the great economic crisis in the 1930s, peat cutting was an important source of income for the residents of Bürmoos. In private or community-owned peat cuttings as well as in designated areas owned by the Salzburg state government, peat was allowed to be cut by the population. The heating material was used for personal use, but also as a means of payment for merchants.

In 1947, the Austrian Nitrogen Works AG Linz started the large-scale industrial production of fuel peat and peat waste with around 130 employees ; From the mid-1950s, only peat was produced. In 1958, the milling dismantling began and was operated until 2000.

The loamy subsoil of the moor was probably used for brick extraction before the middle of the 19th century. The company flourished for a long time and closed in 1976.

The culture of mud baths that emerged in the 19th century, as it also existed for a long time in the region in the Salzburg Moosstrasse , did not exist in the Bürmooser Moor and Weidmoos area at that time. The St. Felix mud bath (located in the municipality of Sankt Georgen) was founded in 1923 and still exists today as a health resort with its own moor extraction.

Infrastructure

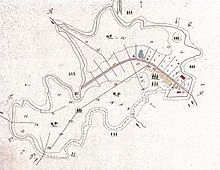

It all started with the development of the Bürmooser Moor in the eastern area near Zehmemoos. In the course of this, a two-kilometer long road was first created, which is considered the first connection between Lamprechtshausen and today's Bürmoos and still exists today as a Grundlose Straße . The name indicates the unsteady subsoil and in the naming it follows on from the 1.5 m deep Grundlose Lake , which was present here at the time and which is already mentioned by Hübner.

In the further area of the beginning of the road a peat store was built, where the peat transported by rail was also reloaded onto the Salzburg local railway from 1896 .

- Bockerlbahn

For the purpose of peat transport, a field railway called the Bockerlbahn was laid in the Bürmooser Moor from 1882 and a little later in the neighboring Weidmoos . The 600 mm wide narrow-gauge railway was 14 kilometers long at the beginning of the 20th century, and at the time of mechanical peat extraction it was 24 kilometers long. Over time, the vehicle fleet consisted of a total of 14 locomotives, 5 people and around 150 peat beds . The last peat transport was carried out at the end of June 2000 and operations ceased in October of that year.

In the course of the renaturation by the Torferneuerungsverein Bürmoos, it was decided to largely dismantle the rail network. Attempts to preserve part of the railway on the one hand as an industrial monument and on the other hand for tourist purposes have had little success. In the visitor center you can see a locomotive and three cars as well as another three cars in the Lamprechtshausen roundabout. Remnants of track still exist mainly in Weidmoos.

Finds

The area was probably already settled in prehistoric times. During excavation work in 1851 a well-preserved bog body was found at a depth of six meters, the age of which is dated to the Neolithic .

In 1944, bronze needles were found at a pond on Grundlose Straße, from which a Celtic settlement is derived.

nature

The Bürmooser Moor was originally part of a large moor complex in the foothills of the Alps , the remainder of which is also formed by the adjacent Weidmoos. It lies in a hollow between terminal moraines from the last Ice Age at 435 m above sea level. A. . Before the drainage and peat extraction, it was a raised bog of around 200 hectares .

With the beginning of peat mining, the land also changed. Although the manual dismantling left behind a changed landscape, it was still moor-like and definitely rich in species. In contrast, mechanical peat extraction left a completely dry, desert-like, largely dead landscape. Many Bürmoos residents did not want to accept that. In 1985, the first attempts to renaturate the pitted areas began. In 1993 the Torferneuerungsverein Bürmoos was founded. Significant areas have now been renatured. The water was backed up again, wet biotopes were created and numerous trees, shrubs and other plants were planted. The Torferneuerungsverein has received several prizes for its efforts in this regard, and the Bürmooser Moor was declared a European bird sanctuary, Natura 2000 , in 2002 and a nature reserve in 2008 . The size of the protection zone is around 58 hectares.

The Bürmooser Moor has meanwhile become a second-hand habitat that is home to numerous rare plants, amphibians, reptiles and birds, many of which were believed to be extinct in the area. The moor is significant as a bird sanctuary in that the water and wet areas alternate with wood and provide important breeding, resting and wintering areas for the animals. The following were seen as important representatives: white-starred bluethroat , great egret , common snipe , bittern and others. Of the amphibians and reptiles include great crested newt and agile frog and other species of frogs and significant sand lizard , slow worm , grass snake , smooth snake and viper available. In addition, the beaver contributes significantly to the formation of the wetlands. More and more typical species from the plant kingdom are settling on the litter and wet meadows, such as Siberian iris , spotted and broad-leaved orchid, and the swamp hairline . Furthermore, small parts of the original raised bog vegetation have been preserved, where, among other things, peat moss , round-leaved sundew , cranberries and heather grow. Water hose species, frog spoons and reeds thrive on the water reservoirs .

A nature trail has existed in the natural area of the municipality right into the protected area since 1996, explaining the flora and fauna of the Bürmoos Moor and its history. There is a hiking trail and a visitor center in the reserve itself.

Along with the clay mining, a brick pond was created , which was made available to the general public in the 1970s when the brick factory was closed. The former Waha-See , today mostly Bürmooser See , officially also called Bürmooser Weiher , is a recreation area and also serves as a fishing water.

Lore

The economic past explains why the moor has played a central role in the identity of the Bürmoos population in the past and present, especially since the community was created thanks to the immigration of workers from different countries; first for the extraction of the peat available here and later by those who were employed in the glassworks, which was built here not least because of the high-quality peat used as heating material. The local history association Bürmoos succeeded in opening the peat-glass-brick-museum in the town center , which is dedicated to the industrial history and thus to the foundation of the community.

Two sculptures in the town center also commemorate economic history: a pair of statues shows a glass blower and a girl carrying peat, and peat, glass and bricks are used as materials in Werner Pink's Gate of the Future .

In addition to the location and the street name for people who are connected with the history of the bog, still exists in the district Zehmemoos the Torfwerkgasse , reminiscent of the former operation.

- The Bürmooser Moor in literature

As head of the former Salzburg peat bog recycling company , a Dr. G. Thenius, who after leaving the company published a book entitled Die Torfmoore Österreichs , which deals almost exclusively with what can be produced with the clay and peat of the Bürmooser Moors. The book is more a fiction than a realistic non-fiction book.

The economic development of the bog and the related emergence of the village Bürmoos is traced in the literary trilogy The glass blowers of Bürmoos of Georg Rendl , the first part of people in the bog is first published in the 1935th

literature

- Adolf Andreaus: The moor of Bürmoos. Vegetation, structure and history. Diploma thesis, University of Salzburg, 2002.

- Hans Schreiber: The moors of Salzburg in a scientific, historical, agricultural and technical relationship. Publishing house of the German-Austrian Moor Association in Staab, Bohemia; Staab 1913.

Web links

- State of Salzburg: Renaturation of the Bürmooser Moor

- ORF Salzburg: Bürmooser Moor - simple beauty

- Bürmooser Moor at euregio-salzburg.info

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Measurement on the official geographic information system of the State of Salzburg ( SAGIS ).

- ↑ Ingo Reiffenstein and Thomas Lindner: Historical-Etymological Lexicon of Salzburg Place Names (HELSON) . Volume 1 - City of Salzburg and Flachgau, Edition Tandem, Salzburg 2015 [= 32nd supplementary volume to the communications of the Society for Salzburg Regional Studies ], ISBN 978-3-902932-30-3

- ^ Franz Hörburger : Salzburg Place Name Book , edited by Ingo Reiffenstein and Leopold Ziller, ed. from the Society for Salzburg Regional Studies , Salzburg 1982

- ↑ See Kluge. Etymological dictionary of the German language , edited by Elmar Sebold, 24th, revised and expanded edition, Berlin: de Gruyter 2002 (CD-ROM) and Etymological dictionary of German , developed under the direction of Wolfgang Pfeifer, 7th edition, dtv, Munich 2007, ISBN 3-423-32511-9 .

- ^ A b Lorenz Huebner : Description of the archbishopric and imperial duchy of Salzburg with regard to topography and statistics. Volume 1: The Salzburg Flat Country; Salzburg, 1796, p. 122. Retrieved on August 1, 2019 .

- ^ A b Hans Schreiber: The moors of Salzburg in a scientific, historical, agricultural and technical relationship. Publishing house of the German-Austrian Moor Association in Staab, Böhmen, Staab 1913, p. 164.

- ^ Geographical Information System of the State of Salzburg ( SAGIS ), Layer Franciszäischer Cadastre.

- ^ Hans Schreiber: The moors of Salzburg in a scientific, historical, agricultural and technical relationship. Publishing house of the German-Austrian Moor Association in Staab, Böhmen, Staab 1913, p. 150.

- ↑ Torferneuerungsverein Bürmoos: Torfkurier, Edition 1/2012, p. 12. Accessed on August 2, 2019 .

- ↑ According to Schreiber (1913), p. 161. There, however, it is also noted that the size specifications for bog areas can be very different, as there are different definitions of what is counted as bog area.

- ↑ Andreaus (2002), p. 5.

- ↑ Bürmoos local history. Retrieved August 2, 2019 .

- ^ Association History Bürmoos: Ortschronik ( Memento from February 13, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d Cf. the information in: Municipality of Bürmoos: Ortschronik. Retrieved August 2, 2019 .

- ↑ a b The Bockerlbahn in Bürmoos. Retrieved August 3, 2019 .

- ^ Lorenz Huebner : Description of the Archbishopric and Imperial Duchy of Salzburg in terms of topography and statistics. Volume 1: The Salzburg Flat Country; Salzburg, 1796, p. 123. Retrieved on August 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Torferneuerungsverein Bürmoos: Torfkurier, Edition 1/2012, p. 9. Accessed on August 2, 2019 .

- ^ State of Salzburg: Nature Conservation Book (nature reserve), accessed on August 5, 2019.

- ^ State of Salzburg: Nature Conservation Book (European Protected Area ), accessed on August 7, 2019.

Coordinates: 47 ° 59 ′ 58 ″ N , 12 ° 55 ′ 40 ″ E