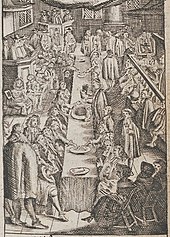

Bread and wine in the sacrament service

Bread and wine are served to participants in the churches of the Reformation at the sacrament service . The term Last Supper is a word coined by Martin Luther . He emphasized the meal character of the Eucharistic celebration and thus referred to early Christianity ( 1 Cor 11:20 LUT ).

The Reformers used in the 16th century continues wafers ( wafers ) and sacramental wine , while theology and liturgy changed. In Reformed churches it then became important to use everyday bread for the sacrament because it would fill and nourish. In the Church of England the question of whether wafers or white bread was decided in favor of white bread after intensive discussion around 1600. The celebration of the Lord's Supper “ under both guises ” also meant, compared to Roman Catholic practice, that a larger quantity of wine was required. The wine can (Photo) is a specifically Protestant liturgical device.

Christianity became a world religion through colonization and mission . Christian communities sprang up in areas where neither grain nor viticulture was indigenous. Long-distance trade, however, was hardly able to import flour and wine from Europe - at best as luxury goods and, due to transport, of very poor quality. The lack of imported wine and the negative experiences with brandy led to the “two-wine theory” in North America in the 19th century - Jesus did not drink alcohol, but grape juice (“unfermented wine”), and so it should also at the Lord's Supper being held. In the mission it was added that bread and wine as European food had no symbolic value for the new converts; on the other hand there were indigenous foods that had a similar meaning in the respective culture.

Last Supper during the Reformation

Wittenberg Reformation

In 1525, Martin Luther refused to design the Lord's Supper as an imitation of the meal of Jesus with his disciples in Jerusalem. Ironically, he suggested that the Lord's Supper should be left until all issues had been clarified: “Item wey we do not know and the text does not exist, whether it was red or blanck weyn, whether it was semlen or barley bread, we will ynn dem Zweyffel the weyl have to leave the event until we are certain that we generally do not make any external thing about anything other than Christ as an example. "

Luther therefore considered it unimportant whether red or white wine was used at the Lord's Supper. But since 1523 he criticized the practice of diluting the wine with water during the Eucharist. Luther may not know or consider it relevant that this was common in antiquity. He saw in the mixture of wine and water a reference to the fact that blood and water had flowed out of Christ's side wound on the cross ( Jn 19.34 LUT ). But Jesus Christ did not order that wine and water be mixed at the Lord's Supper. Pure, unmixed wine is a fitting symbol for the pure teaching of the gospel. Luther consciously took the same position as the Armenian Apostolic Church , which was therefore condemned by Rome as heretical.

Even in Luther's day there were Christians who could not or would not drink wine. Luther had no understanding for this: “You shouldn't take anything other than wine ( quam vinum! ) But if you can't use wine ( sed si vino uti non potest ), you shouldn't…” Johannes Brenz, on the other hand, advised you to take the wine with you Dilute water. Veit Dietrich and Hoe von Hoenegg explained that a few drops of wine in a glass with water were enough. In the 17th century, Luther's rigid stance was represented again.

Philipp Melanchthon was asked at the Regensburg Religious Discussion (1541) how the Lord's Supper should be celebrated under both guises when wine is not available, or at least not available to the whole community. He replied that, strictly speaking, the Scriptures did not speak of wine, but of the chalice. This can be understood to mean that other drinks are also permitted in the event of an emergency. This situation occurred in the Three Crowns War , when Lutheran Sweden could no longer import wine due to a sea blockade in 1564. Some of the clergy around Johannes Nicolai Ofeegh, the Bishop of Västerås , spoke out in favor of celebrating the Lord's Supper with water, milk, mead or beer if it was not possible otherwise. Especially in times of need, the Lord's Supper is a strengthening for the believers. On the other hand, the group around Archbishop Laurentius Petri prevailed in the so-called liquorist dispute : If wine was not available, communion should not be celebrated at all. For Petri, the lack of wine in Sweden was a divine punishment that should be borne in repentance. The wine may be diluted with water, but not replaced by another drink, just as you cannot use apples or pears instead of bread.

Swiss Reformation

In Zurich, on Maundy Thursday , April 13, 1525, a Reformed communion ceremony took place, which more clearly than the Wittenbergers broke with tradition. The liturgy was written by Huldrych Zwingli . The idea of the communal meal was new. As in the parable of the great feast , the congregation gathered around the Lord's table with their pastor. In the front of the church there was a table with unleavened bread and wine. This unleavened bread was shaped like a square host embossed with an image of Christ. Church servants brought the bread in wooden bowls to the participants in the celebration; each broke off a piece. The participants in the meal served each other in wooden cups. It was not a dinner table ; the congregation stayed in its place (since there were probably no church stalls, that means people were standing or kneeling).

In 1557 John Calvin was confronted with the question of how one could celebrate the Lord's Supper on the American continent, namely in a planned Huguenot colony in Brazil ( France Antarctique ). Here people lived on water, fruits and baked roots. Calvin said that Jesus needed bread and wine because they were common foods in Judea. "Who [...] obeys need instead of wine, uses another drink common in the area, should act according to the will and intention of Christ." In his main work Institutio Christianae Religionis in 1559 he also formulated a pragmatic position: It is irrelevant whether "whether The faithful take the bread in their hand or not, whether they distribute it among themselves or whether everyone eats what has been given him, whether they give the cup in the hand of the deacon or pass it on to the neighbor, whether the bread is leavened or unleavened and whether the wine is red or white. ”In Geneva, the Hôpital Général was responsible for supplying the churches with communion bread and wine and cultivated its own vineyards in Peney, Satigny and Bossey.

Anabaptism

As a persecuted minority, Anabaptists celebrated the Lord's Supper only rarely and in a very simple form in the 16th century. During the Easter or Pentecost service of the Moravian Hutterites , plates with bread slices and wine cans were on the tables. When wine was not available, Anabaptist groups celebrated the Lord's Supper with bread or rolls.

Anglican Church

In 1549, the Book of Common Prayer stipulated that hosts should be used as Eucharistic bread, but without imprint, and somewhat larger and thicker than traditionally so that they could be divided into pieces. The second edition in 1552 approached the reformed custom and stipulated that normal wheat bread of the highest quality should be used. The edition of 1559 reiterated that should be used at the Last Supper bread, how it used also at the table, but "the best and purest wheat bread, which is available." A decree ( Injunction ) Elizabeth I from the same year, however, stated that the sacramental bread should be simple and unprinted, round, but somewhat larger and thicker than the wafers common to Catholics. The first generation of Elizabethan bishops tried to enforce these Protestant hosts in general, but some of the parishioners did not accept them because they were Catholic. Edmund Grindal , the Bishop of London, tried in 1567 to convince the London nonconformists by arguing that this was the same communion bread that was also used in Reformed Geneva. Around 1570 the uniform introduction of hosts had failed, some clergymen used bread and some parishioners protested and demanded wafers. In the Anglican clergy, the majority of those who used wheat bread grew, despite popular opposition. In 1584, Bishop William Overton of Lichfield issued the first host ban for his diocese. It was blocked by Archbishop John Whitgift and revoked by the High Commission . During the visitations in the 1580s, the only question asked was whether bread would be served at the Lord's Supper according to the Book of Common Prayer, and the disposition in favor of the hosts was ignored. The unrest in the population was considerable, in some communities Easter services were boycotted because the believers wanted hosts. Archbishop Richard Bancroft wrote in 1604 the use of "fine white bread and good and wholesome wine" in canonical law; the meanwhile general practice has thus been made binding.

17./18. century

Since the Confessio Sigismundi in 1613, breaking bread has been the hallmark of the Reformed celebration of the Lord's Supper. For this purpose, they took “natural and wholesome bread”, which satiates and nourishes people ( Psalm 104 ), which cannot be said of the Catholic and Lutheran host (“wafers and sham bread”). In special cases a customary drink could be used instead of wine.

When Frederick V of the Palatinate became King of Bohemia in 1619, he commissioned Abraham Scultetus to introduce Calvinism to his new subjects. This included the fight against the "papist hosts". They were replaced by bread, rolls and wide cakes, cut into long strips and given to communicants in bowls. During the solemn Supper in Prague's St. Vitus Cathedral at Christmas 1619, yeast pastries ( collapses ) were used to emphasize the difference to hosts. This remained a brief episode, but shows how the Lord's Supper gained importance in Calvinism. The French National Synod also decided in 1620 that "ordinary bread" ( pain commun ) should be used at the Reformed Last Supper .

The Lutheran theologians actually tended to explain the question of bread or the host as an adiaphoron and, in the Thirty Years' War , obeying the need, even celebrated the Lord's Supper with bread. But the more Calvinists made the leavened bread used by them a denominational mark of distinction, the more the host became a hallmark of the Lutheran Lord's Supper. At the end of the century, the denominational quarrel had become less explosive. For the Enlightenment theologian Wilhelm Abraham Teller in 1764 it made no difference whether the bread was leavened or unleavened, broken or cut, the wine pure or mixed with water. He recommended hosts and mixed wine as a kind signal to the Roman Catholic Church ("proof of indulgence in indifferent ceremonies").

19th century

"Unfermented Wine"

The fact that the revival movement, which was largely supported by Methodists , made the fight against alcohol one of its concerns, was due to the special circumstances in the USA. High-proof spirits dominated here, as wine-growing was not successful for a long time and beer brewed in the English style could hardly be stored. The negative effects of alcoholism were evident. Wine was only available as an expensive import from Europe in settlements on the east coast. The Protestant colonists in the interior made use of diluted brandy for the Lord's Supper. Another option was to add brandy to the expensive imported wine. Other communities used fruit wine or an alcoholic brew of their own recipe. All of this was perceived as very unsatisfactory in Methodist churches and aroused a strong need to celebrate the Lord's Supper “properly”, namely as Jesus Christ instituted it. In this search movement, Moses Stuart, a congregational biblical interpreter, published the study Scriptural View of the Wine-Question in 1848 , in which he presented his “two-wine theory”: In antiquity and in the Bible, it was always fermented and “unfermented wine “( Common term for grape juice among prohibitionists ). At the wedding in Cana , Jesus turned water into unfermented wine, and grape juice was also on the table at Jesus' last supper in Jerusalem.

Raisin wine The fact that Jesus and his disciples did not drink wine at the Last Supper in Jerusalem was justified by the fact that fermented as Chametz during the Passover festival was forbidden according to the Jewish ritual law. That is the view of leading contemporary rabbis. Mordecai Noah , a prominent Jewish journalist from New York with no rabbinical training, was quoted particularly frequently as having shared his recipe for raisin wine with Christian prohibitionists; this is the actual traditional Passover wine. He was interviewed as a Jewish expert and explained to the New York Evening Star (February 19, 1836): "Unfermented wine [...] was used exclusively in those times, just as it is today: at Passover as a wine over which the blessing is spoken, probably also at the Last Supper, and it should be the wine that is needed on the sacrament table. ”With raisin wine, Christian Prohibitionists, in their opinion, returned to the authentic drink of early Christianity that had been displaced by fermented wine for centuries. An infusion of water and raisins was indeed used for ritual purposes in 19th century American Jewish communities because kosher wine was not available. He met before in European Jewish recipe books and seems to have a drink of Marranos return, these crowded into the underground Jewish group prepared with its production on Passover. The custom of raisin wine in North America continued in Jewish communities into the 1870s, even when rabbis pointed out that wine was not a chametz in the sense of Jewish ritual law. Mordechai Noah's expertise was contested, however, because the representatives of the “one wine theory” also questioned Jewish sources. In Europe, it was learned, kosher wine was common in Jewish families, and only the very poor manage to make a raisin infusion at Passover.

Grape juice

Ephraim Wales Bull bred the Concord grape variety from American wild vines in 1849 . Thomas Bramwell Welch (1825–1903), a Methodist clergyman, succeeded in 1869 in pasteurizing the juice of the Concord grape . The process had only been known for a few years. Welch's grape juice initially met with little interest. In 1875, however, his son Charles E. Welch had the business idea to market the juice as an alcohol-free communion wine ( Dr. Welch's Unfermented Wine ). The imitation of wine was reinforced by the fact that the juice was bottled in Burgundy bottles. When the Women's Temperance Union, founded in 1873, advertised grape juice at the Lord's Supper, Welch's wine substitute had a breakthrough. Since about 1920, the majority of Protestant churches in the United States have used grape juice in the sacrament.

The "two-wine theory" also came to Great Britain from the USA. The Methodist churches in particular introduced the alcohol-free communion. The Anglican Church did not follow this development. In 1877, Christopher Wordsworth, Bishop of Lincoln, banned the use of grape juice at the sacrament, which the VI. Lambeth Conference 1888 confirmed. An abstinence movement based on the Anglo-Saxon model also arose in German-speaking countries, but the communion wine was not (yet) questioned.

Double hosts

In the negotiations between Lutherans and Reformed people that led to the Old Prussian Union , it was symbolically important whether bread or hosts should be used in the planned Union Church. The solution was a compromise: double wafers with which one could break bread, which is important to the Reformed. Immediately after their introduction in 1830, these new types of “Berlin Hosts” were given the nickname “Spectacle Hosts” and were only used occasionally and not generally in United communities. As a special feature of their Lord's Supper celebration, the Moravian Brethren still uses double wafers, which are broken for two communicants.

Wafer bakery

Wilhelm Löhe suggested a dignified, aesthetically pleasing celebration of the Lord's Supper, which also included quality bread and wine. He not only rejected the opinion of other Lutherans that in areas where bread was not available, the Lord's Supper could be celebrated with the fruit of the bread tree . He also insisted that only existed "real bread and indeed such were needed, as it has also used the Lord, namely Waizenbrote." So he turned against buying hosts at any baker or peddlers, because if they come from potato starch produced , they are unsuitable for the sacrament service. To ensure quality, Löhe founded the Diakonie Neuendettelsau's host bakery in 1858 . Following this example, the Diakonissenanstalt Dresden has been producing hosts in the traditional way since 1866, using "only pure wheat flour and clear water".

Löhe is influenced here by corresponding developments in the Roman Catholic Church. Because a priest who celebrated the Eucharist with materials other than wine made from grapes and bread made from “grain” sinned badly, food manipulation, which was common in the 19th century, was a problem. Own chemical experiments should enable the clergyman to detect inadmissible ingredients (pastoral chemistry ) . It was safer to entrust the wafer bakery and the pressing of mass wine to reliable producers, especially monasteries.

Single goblets

When Robert Koch discovered the tubercle bacillus in 1876 , this led to a pronounced "fear of bacilli" in the population. A decade later, ecclesiastical doctors in the United States raised concerns about drinking from the communion chalice together. In a text with the title " The Poisened Chalice " (The Poisened Chalice) , the physician M. O. Terry advised in 1887 to dunk the bread in the wine (Intinctio) so as not to touch the cup with his lips. Charles Forbes invented a single goblet set made of small glasses (The Sanitary Communion) in 1894 , and around the turn of the century there were different models of how the single goblets could be filled and how to use them to celebrate the Lord's Supper. One possibility was the pouring cup, another option was tap systems, similar to miniaturized drinking fountains in health resorts. The introduction of single goblets was controversial in Methodist communities. Proponents argued that it is possible that every disciple had his own drinking vessel at the Last Supper (here The Last Supper seems to have been received by Leonardo da Vinci). The single chalice also expresses the personal relationship with the Savior particularly well.

Trays of breadcrumbs

The fear of bacilli also changed the way we deal with the Eucharistic bread. The ritual of breaking bread was omitted. In order to avoid unnecessary contact with the food, it became customary in Methodist communities to pass around plates of breadcrumbs, each of which was taken by each communicant. A more far-reaching idea of setting up trays with individual goblets and pieces of bread in the chancel and inviting the communicants to help themselves failed as a “cafeteria communion”: the self-service contradicted the gift character of the Lord's Supper too much.

20th century

Grape juice

It was only after the turn of the century that members of German abstinence associations applied for the use of grape juice at the Lord's Supper. In 1924, two regional churches (Anhalt and Württemberg) allowed their own “Communion celebrations for the abstinent” with grape juice instead of wine. The “two-wine theory” was also taken up anew. Gustaf Dalman disproved this theory with the argument that the grape harvest in Palestine takes place in autumn, but that Jesus and his disciples celebrated the Passover in spring and began the Lord's Supper. Grape juice was not available for this.

In 1979 the VELKD published a handout in which it dealt with the situation of alcoholic people. In order not to stigmatize them, it was allowed to use grape juice in addition to wine at the Lord's Supper. The Lord's Supper with grape juice has become quite common in the practice of Protestant congregations. Liturgists like Karl-Heinrich Bieritz criticize the emptying of meaning by shifting the meaning: " Juice can - as a signifier - hardly realize the abundance of cultural and religious significations that adhere to the symbolic form of wine ," namely festive joie de vivre, abundance of life and hope. Rainer Volp believes that the Protestant Church should not react to the alcoholism problem by generally not using wine, but by making wine and grape juice accessible, leaving the decision up to the people and creating regular security.

Cup movement

In 1903 the Prussian General Synod received a petition to allow alternatives to the communal chalice; however, the synod declined to discuss this subject. In 1904, the Imperial Health Department published an opinion according to which hygiene is sufficient if the goblet is turned a little after each communicant and wiped with a cloth. This encouraged the regional churches to ban individual chalices. The theologians Friedrich Spitta and Julius Smend took the lead in a chalice movement that called for the individual chalice and advertised it in the monthly publication for worship and ecclesiastical art that they both published .

With the outbreak of World War I, the topic disappeared from public interest. However, it returned to the parishes in the 1980s with the fear of AIDS infection. The member churches of the EKD then obtained medical reports, with the result available in 1987 that the risk of being infected with AIDS by drinking from a common goblet was "vanishingly low" and was further reduced by the use of metal instead of ceramic goblets.

According to Volp, it is "ethically imperative" for those in charge of the liturgy to take subjective hygiene concerns in the community seriously and to enable them to choose between communal chalices and individual cups . He rejects individual chalices as "untruthful"; they should be replaced by cups.

Church days

In June 1979, during the 18th German Evangelical Church Congress in Nuremberg, a communion celebration took place, which sent out a signal. 4,500 participants sat or lay on carpets on the floor and shared flatbread and grape juice from ceramic cups in groups. The Kirchentage became a field of experimentation for the connection of Agapemahl and Last Supper, which, however, led to a scandal in Frankfurt in 2001: The Roman Catholic Church forbade its members to participate in an event where people of all denominations and religions had a meal with grape juice, bread , Fruit, vegetables and cheese were invited because they interpreted them as inadmissible ecumenical communion. The EKD responded in 2003 with a memorandum in which it defined the boundaries between agape and communion.

Inculturation of the Eucharistic food

In the South Pacific in particular, Protestant theologians were looking for indigenous and culturally significant symbols with which the gospel could be contextualized . Sione 'Amanaki Havea became known, who developed a “theology of the festival” and a “coconut theology”. The products of the coconut palm are essential for the people of the Pacific Islands. Havea made a number of symbolic references between the coconut palm and Christian beliefs. In 1979 a Culture and Faith workshop was held in the New Hebrides that developed a Eucharistic liturgy with the coconut at its center. The coconut is ritually divided with a knife so that the pulp and coconut water emerge; The latter is collected in a vessel. Havea was a Methodist clergyman in Tonga and first chairman of the Pacific Conference of Churches . Addressing the 6th Assembly of the World Council of Churches in 1983, he said: “We are strangers to grain and grapes, bread and wine. Today that's the coconut. We see the kairos in the ripening of the coconut. "

Dinbandhu Ministries in Yavatmal , Maharashtra , is a Dalit Mission Society founded in 1990 . She also uses coconut pulp and juice in her sacrament celebration, referring to the symbolism of the fruit in Hinduism. The ritual breaking of the coconut symbolizes Christ's giving of life on the cross.

The ceremonial drink Kava is considered to be the epitome of its own culture on the Fiji Islands . Therefore, there was a discussion in the Methodist Church there about whether kava could be used in the Eucharist instead of the culturally foreign wine. In particular, passing around a bowl (tanoa) from which everyone can drink, and through which they become part of a social community, is a parallel to drinking from the cup of communion. A reference to the Bible passage 1 Cor 10.16 LUT is also obvious. In the Roman Catholic Church of Pohnpei (Micronesia), a reconciliation ritual is common, in which kava is used; it has structural similarities with a celebration of the Eucharist. Even so, the Methodists felt that kava was not the right choice as a Eucharistic drink and decided against it.

21st century

Wine or grape juice, individual goblets or communal goblets

Evangelical Church in Germany

With reference to the Leuenberg Agreement , the EKD orientation aid The Last Supper states that the creation gifts of bread and wine are at the center of the celebration of the Lord's Supper. “Not every piece of food is suitable for making Christ's body and blood present.” The question of whether white bread or wafers and red or white wine are used should not, however, be upgraded to a fundamental question. The Lord's Supper with grape juice should remain the exception. The orientation guide states that in some church parishes forms of celebration of the Lord's Supper are common in which individual chalices are used. She points out that drinking from the communal goblet corresponds better to the words of institution ("drink everyone from it") and also to "the fact that in the Lord's Supper the congregation is united not only in communion with Christ, but also with one another."

Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church (SELK)

Only wine is used to celebrate Holy Communion, usually white wine. With grape juice there is no longer the certainty of acting in accordance with the commission of Jesus Christ. The use of individual goblets is not permitted because drinking from the common goblet has theological significance.

Gluten-free hosts

Since a growing proportion of the population was diagnosed with gluten intolerance ( celiac disease ), the question for the churches has been how these people can take part in the Lord's Supper. Without gluten it is not possible to bake wheat flour wafers. Gluten-free hosts are therefore made from other ingredients. The Neuendettelsau host bakery, for example, uses rice, corn and potato flour, ingredients that its founder Löhe wanted to exclude in the 19th century. Even more so, you can't bake gluten-free wheat bread, so Reformed communities can choose between hosts or white bread made from rice and corn flour. The Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church (SELK) describes it as "controversial" whether wafers made from potato starch correspond to Christ's mandate to institute the Lord's Supper, and points out that their use in the Roman Catholic Eucharistic celebration is generally not permitted. Roman Catholic arguments against the use of gluten-free bread in the celebration of the Eucharist, on the other hand, are expressly judged to be insignificant in Anglicanism.

Inter-Anglican Liturgical Commission report 2009

The Anglican Communion is a world church that has opened up to inculturation more than the Roman Catholic Church. A survey of 29 provinces or churches, which materials are used in the celebration of the Eucharist, showed that the following motives justify a substitution of bread or wine: concern for allergy sufferers and alcoholics, costs, rejection of alcohol (abstinence as church doctrine), unavailability, legal provisions . For some provinces it is practically impossible to celebrate the Lord's Supper with wine because of Islamic law. The alternatives mentioned were:

- for wheat bread: biscuits made from rice flour, gluten-free bread, biscuits, round cakes;

- for grape wine: grape juice, non-alcoholic wine, Coca-Cola, Fanta, banana juice, fruit wine (pineapple or passion fruit), infusion of raisins in boiling water.

It was reported from the Philippines that ecumenical irritation arose when the Anglicans used local types of bread and wine (rice cakes, rice wine) at the Eucharist. The Pacific Theological College, as the central training center for Protestant clergy on the Pacific Islands, offers a choice of whether to use bread and wine or coconuts at the Lord's Supper. The use of kava was also mentioned. First Nations Anglican communities , according to the survey, reject alcohol because of its negative historical connotations and sometimes replace it with peyote .

The commission found that world trade made it unclear which foods are cultural imports and which are part of local culture. Soft drinks e.g. B. are imports, but are regionally perceived as part of their own African culture. As a result, the Commission recommended that bread and wine should not be defined precisely (and consistently); it was sufficient that foods were used that could be called bread and wine at the celebration in a particular historical and cultural context.

literature

- Anselm Schubert : God Eat: A Culinary Story of the Last Supper. C. H. Beck, Munich 2018. ISBN 978-3-406-70055-2

- Christopher Haigh: 'A Matter of Much Contention in the Realm': Parish Controversies over Communion Bread in Post-Reformation England. In: History 88/3 (2003), pp. 393-404.

- Daniel Sack: Whitebread Protestants. Food and religion in American culture. Springer, New York 2000. ISBN 978-0-312-29442-7 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Josef Andreas Jungmann : "Last Supper" as the name of the Eucharist . In: Journal for Catholic Theology 93/1 (1971), pp. 91–94, especially p. 91: “A second time [after the 1st century], a designation of the Eucharistic celebration that emphasizes the character of the meal appears again in the 16th century, with Luther. "The Lord's Supper" gradually became the common name among the Protestant communities. "

- ↑ Since the Carolingian era, the Eucharistic bread has been a pastry made from unleavened wheat flour and water in the Western Church ; it was called the oblate (Latin oblata ), after the consecration it was called the host (Latin hostia ); both Latin terms mean offering. Cf. Helmut Hoping : My body given for you: history and theology of the Eucharist . 2nd, extended edition, Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2015, p. 180.

- ↑ Martin Luther: Against the heavenly prophets, from the images and sacrament . WA 18, p. 115.

- ^ Martin Luther: Formula Missae et Communionis. WA 12, p. 211: Sub symbolo vel post Canonem apparetur panis et vinum ad benedictionem ritu solito, nisi quod nondum constitui mecum, miscendane sit aqua vino, quamquam huc inclino, ut merum potius vinum paretur absque aquae mixtura, quod significatio me male habeat […] Merum vinum enim pulcher figurat puritatem doctrinae Euangelicae.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 120 f.

- ↑ Martin Luther: WA Tischreden 5, p. 203.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 123.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 124.

- ↑ Mia Korpiola: Archbishop Laurentius Petri (1499-1573): the respected authority of the Swedish Reformation . In: Kjell Å. Modéer, Helle Vogt (Ed.): Law and the Christian Tradition in Scandinavia: The Writings of Great Nordic Jurists . Routledge, Oxon et al. 2021, pp. 105–127, here p. 110f.

- ↑ Peter Opitz : Ulrich Zwingli: Prophet, Heretic, Pioneer of Protestantism . TVZ, Zurich 2015, p. 70.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 125 f.

- ↑ Johannes Voigtländer: A festival of liberation: Huldrych Zwingli's doctrine of the Lord's Supper . Neukirchener verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2013, p. 67 and note 32.

- ↑ a b Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 130.

- ↑ John Calvin: Institutio 4.17.43.

- ↑ Christian Grosse: Les rituels de la cène: le culte eucharistique réformé à Genève (XVIe - XVIIe siècles) . Droz, Geneva 2008, p. 230f.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 127.

- ↑ Christopher Haigh: 'A Matter of Much Contention in the Realm': Parish Controversies over Communion Bread in Post-Reformation England , 2003, pp. 394-396.

- ↑ Christopher Haigh: 'A Matter of Much Contention in the Realm': Parish Controversies over Communion Bread in Post-Reformation England , 2003, p. 400.

- ↑ Christopher Haigh: 'A Matter of Much Contention in the Realm': Parish Controversies over Communion Bread in Post-Reformation England , 2003, p. 403.

- ^ Confessio Fidei Johannis Sigismundi, Electoris Brandenburgici

- ↑ Ernst Koch : Last Supper II. Church history 4th, 17th and 18th centuries . In: Religion Past and Present (RGG). 4th edition. Volume 1, Mohr-Siebeck, Tübingen 1998, Sp. 28-29.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 134 f.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 156.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 157.

- ^ Karen B. Westerfield Tucker: American Methodist Worship , Oxford University Press, New York 2001, p. 150. Cf. Wilhelm Löhe: Confession and Communion Book for Evangelical Christians. For use both in and outside of worship . 5th, increased and improved edition Nuremberg 1871, p. 224: “But it is undoubtedly unworthy to mix the Lord's Supper with brandy, as is complained about from America, and when the communicants accept the highly profane steam and taste while enjoying it have to."

- ^ Karen B. Westerfield Tucker: American Methodist Worship , Oxford University Press, New York 2000, pp. 150 f.

- ^ John L. Merrill, The Bible and the American Temperance Movement: Text, Context, and Pretext . In: Harvard Theological Review 81/2 (A1988), pp. 145–170, here p. 156.

- ↑ Jonathan D. Sarna: Passover Raisin Wine, The American Temperance Movement, and Mordecai Noah: The Origins, Meaning, And Wider Significance Of A Nineteenth-Century American Jewish Religious Practice . In: Hebrew Union College Annual 59 (1988), pp. 269-288, here p. 280.

- ↑ Daniel Sack: Whitebread Protestants. Food and religion in American culture , New York 2000, pp. 18-21.

- ↑ Jonathan D. Sarna: Passover Raisin Wine, The American Temperance Movement, and Mordecai Noah: The Origins, Meaning, And Wider Significance Of A Nineteenth-Century American Jewish Religious Practice . In: Hebrew Union College Annual 59 (1988), pp. 269-288, here pp. 270-274.

- ↑ Jonathan D. Sarna: Passover Raisin Wine, The American Temperance Movement, and Mordecai Noah: The Origins, Meaning, And Wider Significance Of A Nineteenth-Century American Jewish Religious Practice . In: Hebrew Union College Annual 59 (1988), pp. 269-288, here p. 281.

- ↑ Thomas Pinney: A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition . University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles / London 1989, p. 388. Karen B. Westerfield Tucker: American Methodist Worship , Oxford University Press, New York 2001, p. 151.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 177.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 178.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, pp. 160–162. Cf. Martin Schian : Grundriß der Praxis Theologie , Töpelmann, Gießen 1922, p. 162: "In united congregations, in order to accommodate the Reformed custom, double hosts are sometimes used, which are broken before the distribution."

- ↑ Evangelical Brothers Unity: The Lord's Supper in the Moravian Brethren .

- ^ Wilhelm Löhe: Confession and Communion Book for Protestant Christians. For use both in and outside of worship . 5th, increased and improved edition Nuremberg 1871, pp. 221–223.

- ^ Diakonissenanstalt Dresden: Brochure Host Bakery .

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, pp. 168–174.

- ^ Karen B. Westerfield Tucker: American Methodist Worship , Oxford University Press, New York 2001, p. 152.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 184.

- ^ Karen B. Westerfield Tucker: American Methodist Worship , Oxford University Press, New York 2001, p. 153.

- ^ Karen B. Westerfield Tucker: American Methodist Worship , Oxford University Press, New York 2001, p. 154.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 180.

- ↑ Gustaf Dalman: The wine of the last supper of Jesus . In: Evangelical Lutheran Church Newspaper, May 21, 1931.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 192 f.

- ^ Karl-Heinrich Bieritz: Liturgy . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2004, p. 233.

- ^ A b Rainer Volp: Last Supper V. Practical-theological . In: Religion Past and Present (RGG). 4th edition. Volume 1, Mohr-Siebeck, Tübingen 1998, Sp. 49-52.

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 184 f.

- ↑ Evangelical Lutheran Regional Church of Hanover: Circular Decree K3 / 1987, Hygienic handling of the Holy Communion chalice .

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, pp. 190–192.

- ^ Randall G. Prior: Contextualizing Theology in the South Pacific: The Shape of Theology in Oral Cultures (= American Society of Missiology Monograph Series 41). Pickwick Publications, Eugene 2019, pp. 97-99.

- ↑ World Council of Churches: 2000: The year in review: Obituaries .

- ^ Roger E. Hedlund: Christianity Made in India: From Apostle Thomas to Mother Teresa . Fortress Press, Minneapolis 2017, p. 159 f.

- ^ Matt Tomlinson: Ritual Textuality: Pattern and Motion in Performance . Oxford University Press, pp. 48-53.

- ↑ The Lord's Supper. A guide to the understanding and practice of the Lord's Supper in the Protestant Church, 3.5 Which forms of the elements are possible?

- ↑ The Lord's Supper. A guide to understanding and practicing the Lord's Supper in the Protestant Church, 3.2 In what form should the Lord's Supper be celebrated?

- ↑ Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church: Lexicon, Article Wine .

- ↑ Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church: Lexicon, article single chalice .

- ↑ Deacono : Hosts from Neuendettelsau .

- ↑ Anselm Schubert: God eat: A culinary story of the Last Supper . Munich 2018, p. 193 f.

- ↑ "This is my body" - crumbly, but gluten-free. In: www.evangelisch.de, May 31, 2011.

- ↑ Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church: Lexicon, article Hostie .

- ↑ Eucharistic Food and Drink. A report of the Inter-Anglican Liturgical Commission to the Anglican Consultative Council , November 11, 2009, www.anglicancommunion.org., Here p. 3.

- ↑ Eucharistic Food and Drink. A report of the Inter-Anglican Liturgical Commission to the Anglican Consultative Council , November 11, 2009, www.anglicancommunion.org., Here p. 18.

- ↑ Eucharistic Food and Drink. A report of the Inter-Anglican Liturgical Commission to the Anglican Consultative Council , November 11, 2009, www.anglicancommunion.org.