Charles Marie de La Condamine

Charles-Marie de La Condamine (born January 28, 1701 in Paris , † February 4, 1774 ibid) was a French traveler, mathematician , encyclopedist and astronomer . He gained notoriety in particular through his trip to South America 1735-1745 and as a committed advocate of smallpox vaccination in the second half of the 18th century .

From 1743 to 1745 Charles-Marie de La Condamine traveled to the Amazon and contributed significantly to a better knowledge of the region, both geographically , botanically and zoologically . La Condamine is considered to be a pioneer of Alexander von Humboldt , who a good 50 years later made several trips to South America and, among other things, to the Amazon region.

La Condamine's commitment to smallpox vaccination is also significant, where it contributed significantly to the spread of inoculation in France and Europe. Charles-Marie de La Condamine was a member of the Académie des Sciences and the Académie française . He was internationally networked with numerous enlightened intellectuals of his time.

Beginnings (1701–1735)

Charles-Marie de La Condamine was born in 1701 in Paris as the son of the tax officer Charles de La Condamine (1649–1711) and his wife Marguerite-Louise de Chources (* approx. 1670–1710). The couple had two children and Charles Marie had an older sister, Anne Marie Louise de La Condamine (* approx. 1700–1771). In the first years La Condamine was taught at a boarding school and then attended the Collège Louis-le-Grand , where the renowned Father Charles Porée was his teacher. After completing his school career, La Condamine entered the military and took part in the siege of Roses with a dragoon regiment in the war against Spain in 1719 . A short time later, the young La Condamine disillusioned the military and turned to the enlightened and scientific circles of Paris. Here he gave math lessons to Louis de Tressan, who was only 14 years old at the time, and made friends with Voltaire . Together, he and Voltaire decided to “crack” the Paris lottery from 1729–1730: The background was a calculation by La Condamines, according to which one would achieve a net profit of about 1 million livres if one bought up all of the tickets. The two succeeded in the coup - the responsible minister had miscalculated - and they each won 500,000 livres in the deal.

Entry into the Académie des Sciences (1730)

It was his mathematical and scientific talent and his good contacts that ultimately led La Condamine to the Paris Académie des Sciences : On December 12, 1730 he was appointed adjunct for chemistry there. He published his first work in 1731 on geometric cones and crystalline shapes. Soon afterwards, however, he left Paris and set out on his first voyage: on board a ship led by privateer René Duguay-Trouin , he traveled the Mediterranean to the Levant and spent, among other things, five months in Constantinople . In 1732 he returned with rich scientific results and presented his diverse observations, from the ancient sites of Greece to medical curiosities, as Observations mathématiques et physiques faites dans un voyage de Levant in front of the academy.

Expedition to South America (1735–1745)

The 1730s were, above all, the time of a great fundamental debate in physics: the question of the earth figure . While the traditional doctrine in France (represented by Jacques Cassini , among others ) assumed, following Descartes , that the earth was closer to the equator than to the Poles like a vortex, mainly younger scientists represented, including La Condamine and Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis , the "English" view according to Newton , which, on the contrary, assumed that the earth was flattened at the poles and thus wider at the equator. In order to end this dispute and to determine the "true" shape of the earth (which was also of enormous importance for precise cartography), two expeditions were formed, each of which was supposed to measure a meridian : While Maupertuis set out for Lapland to find one at the Arctic Circle To measure longitude, La Condamine became a member of the second expedition that was sent to South America on the equator - in what was then the Viceroyalty of Peru .

On May 16, 1735, the expedition ran on behalf of Louis XV. in the port of La Rochelle and finally reached the equator in March 1736 after stages in Santo Domingo and Panama . In addition to La Condamine, Louis Godin (director and senior academy member), Pierre Bouguer (a former mathematical “child prodigy”) and Joseph de Jussieu (botanist) were part of the expedition. The group was later supplemented by the two Spanish officers Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa , as well as the Creole cartographer Pedro Vicente Maldonado . La Condamine had a great friendship with Maldonado that went beyond the travel time.

Earth shape measurements (1736–1743)

As early as Santo Domingo, there was considerable tension between the three scientists La Condamine, Godin and Bouguer. All three claimed the leading role in the expedition: while Godin and Bouguer could point to recognition and experience in the academy, La Condamine was the only member to have practical travel experience that was of great value in the inhospitable wilderness. Because of the differences, the paths of the three separated again and again: To get from the port of Guayaquil to Quito , for example , La Condamine decided to choose a more arduous and longer land route alone. The division made it possible for the expedition to make more and different observations at the same time. On the way to Quito, La Condamine had to overcome dense forests and the first mountain ranges of the Andes before it finally reached the city. A little later, La Condamine also traveled alone to the capital of the viceroyalty in Lima to deal with important matters for the expedition. On his travels through Peru, La Condamine examined quinine (and its antipyretic effects), about which he wrote a paper for the academy. The research in South America was extremely diverse, so La Condamine and Bouguer also carried out various observations and experiments in the Andes (including on the Chimborazo ), where research could be carried out at heights that were inaccessible in Europe.

The scientists used the triangulation method to measure the latitude themselves . For this purpose, pyramids were built in the mountains, which then served as sighting points for the measurements. In 1739 they completed the (earth-related) geometric measurements and made additional necessary astronomical measurements in the city of Cuenca . It was not until 1743 that all the work was finally completed. They confirmed Newton's theory: the earth is flattened at the poles .

The scientists began their return journey in different ways: While Louis Godin and Joseph de Jussieu initially stayed in South America, Pierre Bouguer traveled back by ship on a similar route as on the outward journey. La Condamine, on the other hand, chose a more dangerous route to have the opportunity to further new knowledge and research: he decided to cross the continent on the Amazon and then return to France from Cayenne .

Amazon trip (1743–1745)

La Condamine is considered to be the first scientifically educated man to sail the Amazon in its full length. Before him, Spaniards (including Francisco de Orellana , Pedro de Ursúa and Lope de Aguirre ) and Portuguese (including Pedro Teixeira ) had traveled the Amazon in search of gold, spices, power and wealth. In the 17th century it was especially spiritual missionaries (including Cristobal de Acuna , Samuel Fritz ) who ventured into the jungle to convert Indian peoples to Christianity. So while the first travelers traveled on the river for economic, political or religious reasons, at La Condamine research and science were the main concern of the trip for the first time. At the end of the journey, in its relation abrégée d'un voyage… dans… l'Amérique, there was a description of the Amazon from a primarily scientific point of view, which almost completely ignored the adventure. It was not befitting for an Enlightenment traveler to be adventurous; Rationality, precision and science were the ideals of that time, according to which La Condamine also organized and described his trip.

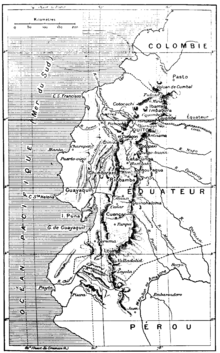

La Condamine made it its primary task to precisely map the river. The maps of Nicolas Sanson (who had never been to the Amazon himself and who drew on the basis of a travel report by Cristobal de Acuna) and the Jesuit priest Samuel Fritz had numerous errors and were made without instruments or measurements. La Condamine, on the other hand, carried out precise astronomical localizations and thus created an extremely precise map of the Amazon region, which became the central product of his journey. After measuring the shape of the earth, the Amazon basin was measured by La Condamine.

But in addition to the cartographic knowledge, La Condamine also collected a large number of other observations, which he recorded in his "Relation". Among other things on curare , the arrow poison of the Indians; the rubber raw material rubber , which is very well known today ; on the animal world (including the electric eel whose peculiar (later identified as electrical) blows puzzled La Condamine) or smallpox and the smallpox vaccination. In Cayenne, the destination of his trip to the Amazon, he also considered a uniform international measure based on the length of the pendulum at the equator. On August 22, 1744, La Condamine left Cayenne and traveled back to Paris via Suriname and Amsterdam , which he reached on February 23, 1745.

Return to Europe (1745–1774)

When La Condamine returned to Europe in 1745, the question that had caused him to leave for South America 10 years earlier had long been answered: the earth has flattened at the poles; Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis explained this to the Academy as early as 1737 and Pierre Bouguer confirmed this on the basis of measurements taken at the equator in 1744. For La Condamine there is no longer an audience to debate the earth form in the Académie des Sciences. So he decides to completely ignore the seven years in Peru and presents the academy with the scientific results of his Amazon trip and, as a concession to a curious readership, also some thoughts on the great myths of the Amazon: the El Dorado , the Muiraquitã and the Amazons . His report, which is both insightful and exciting, has met with extremely positive feedback in and outside the scientific community and makes La Condamine extremely famous. In the long term, he is able to reap the glory of the expedition even before his two colleagues Bouguer and Godin.

After his return to Europe, La Condamine devoted himself primarily to the smallpox vaccination . In August 1756 he married his much younger niece Charlotte Bouzier d'Estouilly (* approx. 1730). Because of the close relationship between him and his wife, he applied for papal consent to marriage, which he received. Despite the age difference and childlessness, the two seem to have had a happy marriage, with Charlotte d'Estouilly loving her husband more like a father and friend. La Condamine spoke several languages and corresponded with intellectuals from all over Europe, including Johann II Bernoulli from Basel and Samuel Formey from Berlin. He also contributed some articles to the Encyclopédie by Denis Diderot and Jean Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert . He fell out with his childhood friend, Voltaire, when Voltaire mocked and ridiculed his great friend Maupertuis in his 1752 satire La Diatribe du Docteur Akakia . From that point on, the two were hostile to each other until the end of their lives. La Condamine's great reputation was also reflected in his affiliation to several learned societies across Europe: He was a member of the Royal Society in London, the Berlin Academy of Sciences and the academies in St. Petersburg and Bologna . La Condamine has been in increasingly poor health since his return. He suffered from hearing loss and increasing paralysis as a result of an illness. Since 1763 he was almost completely paralyzed. When he heard of a new operation to treat his illness, he offered himself up as a test patient, but died in 1774 of the consequences of the operation.

Commitment to the smallpox vaccination (1754–1765)

Even in his youth, La Condamine suffered from smallpox, a disease that attacked about one in 14 people in the 18th century, the so-called "Age of Smallpox", and that was fatal in one of 6 cases. Doctors realized that the disease occurs only once in a lifetime and that it progresses differently depending on the circumstances. Based on these findings, they developed inoculation as an early form of vaccination in which the infection was brought about in a conscious and controlled manner. However, since some healthy people died as a result of the disease through inoculation, the method was extremely controversial in Europe among doctors and scientists. La Condamine, who in South America had experienced inoculation as an extremely successful practice among the Indians, campaigned with great commitment for inoculation. In particular, he wrote three works on the history of inoculation in 1754, 1758 and 1765, which he bundled in 1773 to form the Histoire de l'Inoculation . These were not so much medical texts as a collection of reports of successful inoculations and a critical examination of the negative illnesses (for which he often found external circumstances or errors of the doctors as the cause). La Condamine wrote for “the gentle mothers whose courage needed support” to allow inoculation in their children, as Nicolas de Condorcet put it after La Condamines death .

Entry into the Académie française (1760)

La Condamine was not only a great scientist but also a gifted writer. His writing found its greatest appreciation when he was accepted into the Académie Française in 1760, the welcoming speech was given by Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon . His explicitly literary works include Les Quand from 1760: a critical-satirical response to the play Les Philosophes by Charles Palissot de Montenoy ; Le Pain Mollet of 1765 (published 1768): a short story in verse in which he mocks anti-inoculists; and a posthumous collection of poems. Furthermore, the Histoire d'une fille sauvage trouvée dans les bois , published in 1755, should be mentioned, which is attributed to La Condamine and tells the fate of the “wild” girl Marie-Angélique Memmie LeBlanc , who is said to have grown up alone in the forest until she was 10 years old .

Travels to Italy (1757) and England (1763)

In 1757 La Condamine went on a trip to Italy . Although he originally intended to take a recreational stay there for health reasons, he could not curb his curiosity and brought back the academy with a wealth of various observations: Among other things, he hypothesized the lengths of the ancient Roman units of measurement and examined volcanoes , especially the Vesuvius and visited Pompeii . He summarized his results in his Extrait d'un journal de voyage en Italie for the academy. On this trip he also obtained papal consent for marriage to his niece.

In 1763 La Condamine went on another trip and visited the "motherland" of inoculation: England. He stayed in London for some time and there met several English scholars. Back from England, La Condamine's symptoms of paralysis increased so that this trip was his last.

Honors

In 1935 the lunar crater La Condamine was named after him by the International Astronomical Union , as was the asteroid (8221) La Condamine in November 2002 . In February 1803, a group of small islands in the Australian archipelago Laplace was named after him as Ilots La Condamine .

Fonts

Académie des sciences (selection)

- Observations mathématiques & physiques, faites dans un voyage du Levant en 1731 & 1732. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1732. Paris 1735, pp. 295–322.

- Nouvelle manière d'observer en mer la déclinaison de l'aiguille aimantée. In: Histoire de l'Académie… 1733. Paris 1735, pp. 446–456.

- Manière de déterminer astronomiquement la différence en Longitude de deux lieux peu éloignés l'un de l'autre. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1735. Paris 1738, pp. 1–11.

- De la mesure du pendule à Saint-Domingue. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1735. Paris 1738, pp. 529-544.

- Sur l'arbre du Quinquina. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1738. Paris 1740, pp. 226–243.

- Relation abrégée d'un voyage fait dans l'intérieur de l'Amérique méridionale… In: Histoire de l'Académie royale des sciences… 1745. Paris 1749, pp. 391–492.

- Extraits des opérations trigonométriques, et des observations astronomiques, faites pour la mesure des degrés du Méridien aux environs de l'Équateur. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1746. Paris 1751, pp. 618–688.

- Nouveau projet d'une mesure invariable, propre à servir de mesure commune à toutes les nations. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1747. Paris 1752, pp. 489-514.

- Mémoire sur l'inoculation de la petite vérole. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1754. Paris 1759, pp. 615–670.

- Extrait d'un Journal de Voyage en Italie . In: Académie Royale des Sciences (ed.): Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences… 1757 . Imprimerie Royale, Paris 1762, p. 336-410 ( digitized on Gallica ).

- Second mémoire sur l'inoculation de la petite vérole… 1754 à 1758. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1758. Paris 1763, pp. 439–482.

- Suite de l'histoire de l'inoculation… depuis 1758 jusqu'en 1765. Troisième mémoire. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1765. Paris 1768, pp. 505-532.

Levant (1731-1732)

- Observations mathématiques et physiques faites dans un voyage de Levant… Paris 1735.

- Tunis, le Bardo, Carthage. Extraits inédits du Journal de mon voyage au Levant (May 21-October 6, 1731). In: Henri Begouen (ed.): Revue tunisienne. Hf. 17, Tunis 1898.

- Journal de mon voyage du Levant: [Relation d '] une mission de M. de La Condamine aux Echelles de Barbarie. In: Paul-Emile Schazmann (Ed.): Revue maritime. Paris 1937.

- Voyage au Levant-Alger: Le Voyage de La Condamine à Alger (1731). In: Marcel Emerit (Ed.): Revue africaine. ( ZIP ; 12.7 MB), Vol. XCVIII, Alger 1954, pp. 354-381.

South America (1735–1745)

- Relation abrégée d'un voyage fait dans l'intérieur de l'Amérique méridionale… Paris 1745.

- Lettre à Madame *** sur l'émeute popular excitée en la ville de Cuenca… Paris 1746.

- Journal du voyage fait par ordre du Roi à l'Equateur servant d'introduction historique à la mesure des trois premiers degrés du méridien . Imprimerie Royale, Paris 1751 ( manioc.org ).

- Mesure des trois premiers degrés du méridien dans l'hémisphère austral, tirée des observations de MM. De l'Académie Royale des Sciences, envoyés par le Roi sous l'Équateur . Imprimerie Royale, Paris 1751 ( digitized on Gallica ).

- Relation abrégée d'un voyage fait dans l'intérieur de l'Amérique méridionale, depuis la côte de la Mer du Sud, jusqu'aux côtes du Brésil & de la Guyane, en descendant la riviere des Amazones, par M. de La Condamine , de l'Académie des Sciences, avec une carte du Maragnon, ou de la riviere des Amazones, levée par le même. Nouvelle édition augmentée de la Relation de l'emeute populaire de Cuença au Pérou, et d'une lettre de M. Godin des Odonnais, contenant la relation du voyage de Madame, Godin, son epouse, & c. Jean-Edme Dufour, Philippe Roux, Maastricht 1778 ( manioc.org ).

- Mémoire sur une résine élastique, nouvellement découverte à Cayenne. In: Mémoires de l'Académie Royale. Paris 1751.

- Mesure des premiers trois degrés du méridien dans l'hémisphère austral. Paris 1751.

- Supplément au Journal historique du voyage à l'équateur…. Paris 1752.

Inoculation and smallpox vaccination

- Mémoire sur l'inoculation de la petite vérole. Paris 1754.

- Second mémoire sur l'inoculation… Paris 1759.

- Response from M. La Condamine au défi de M. Gaullard. sl 1759.

- Lettres de M. La Condamine à M. Daniel Bernoulli. sl 1760.

- Lettres de M. de La Condamine à M. le Dr. Maty sur l'état present de l'inoculation in France. Paris 1764.

- Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire de l'inoculation de la petite vérole… Paris 1768.

- Histoire de l'inoculation de la petite vérole… Paris 1773.

Varia

- Lettre critique sur l'éducation. Paris 1751.

- Histoire d'une jeune fille sauvage trouvée dans les bois… Paris 1755.

- Les Quand: addresses à M. Palissot et publiés par lui même. sl 1760.

- Discours prononcés dans l'Académie française ... à la reception de M. La Condamine. Paris 1761.

- Le Pain Mollet. sl 1768.

- Nouveaux délassemens de M. de Voltaire. Lausanne 1773.

- Lettre de MLC à M. Grouber de Groubentail, sur son ouvrage intitulé, La finance politique, réduite en principe & en pratique, pour servir de système général en finance. Paris 1775.

- Choix des poésies de Pezai, Saint-Péravi et La Condamine. Paris 1810, pp. 277-312.

- Achille Le Sueur (Ed.): La Condamine, d'après ses papiers inédits. Amiens 1910.

literature

- Jacques de Guerny: Amazon. Dans le sillage de Charles-Marie de La Condamine. Saint-Germain-des-Prés 2009.

- Raúl Hernández Asensio: El matemático impaciente. La Condamine, las pirámides de Quito y la ciencia ilustrada (1740–1751). Lima 2008.

- Michael Rand Hoare: The Quest for the True Figure of the Earth. Burlington 2005.

- Dario A. Lara: L'amitié de deux hommes de science. Charles-Marie de La Condamine and Pedro Vicente Maldonado. Quito 2005.

- Barbara Gretenkord: Journey to the Middle of the World. The story of the search for the true shape of the earth. Ostfildern 2003.

- Patrice de La Condamine: Charles-Marie de La Condamine. Un homme, une vie, une légende. Cette-Eygun 2001.

- Victor Wolfgang von Hagen : South America is calling. The voyages of discovery of the great naturalists La Condamine, Humboldt, Darwin, Spruce. Vienna 1945.

- Nicolas de Condorcet : Éloge de M. de La Condamine. In: Oeuvres de Condorcet. Vol. 2, Paris 1847.

- Jacques Delille : Discours de réception à l'Académie française. In: Oeuvres de Jacques Delille. Paris 1819, pp. 63-107.

Movies

- Annabel Gillings: The long way to the equator. Universum (TV series) , German adaptation: Sabine Holzer, 2007 (Austria).

- Albert Barillé : Once upon a time ... the discovery of our world . La Condamine - Along the Equator. France 1996/1998. [1] .

- Claude Collin Delavaud: Sur les pas de La Condamine. France 1987.

Web links

- Literature by and about Charles Marie de La Condamine in the catalog of the German National Library .

- Short biography and list of works by the Académie française (French).

- Short biography ( memento of September 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) of the Académie des Sciences (French).

- Short biography from Friedrich Embacher: Lexicon of journeys and discoveries. Amsterdam 1961.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Frank A. Kafker: Notices sur les auteurs of dix-sept volumes de "discours" de l'Encyclopédie. Research on Diderot et sur l'Encyclopédie. 1989, Volume 7, Numéro 7, p. 145.

- ^ Nicolas de Condorcet: Éloge de M. de La Condamine. In: Oeuvres de Condorcet. Vol. 2, Paris 1847, p. 157.

- ↑ Frank Arthur Kafker: The encyclopedists as worth individuals: a biographical dictionary of the authors of the Encyclopédie. Oxford 1988, p. 184.

- ^ A b Francois Le Tacon: Le comte de Tressan, Maupertuis et La Condamine dans les débuts de la Société Royale des Sciences, Arts, et Belles-Lettres de Nancy. (PDF; 144 kB), Nancy 2003.

- ^ René Pommeau: Le jeu de Voltaire écrivain. In: Le jeu au XVIIIe siècle: Colloque d'Aix-en-Provence 30 avril, 1er et 2 May 1971. Aix-en-Provence 1976, pp. 175-176.

- ^ Charles-Marie de La Condamine: Sur une nouvelle manière de considérer les sections coniques . In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1731 . Paris 1734, p. 240-249 .

- ^ Charles-Marie de La Condamine: Sur une nouvelle espèce de végétation métallique . In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1731 . Paris 1734, p. 466-482 .

- ^ Nicolas de Condorcet: Éloge de M. de La Condamine . In: Oeuvres de Condorcet . tape 2 . Paris 1847, p. 162 ff . ( Online in Google Book Search).

- ^ Charles-Marie de La Condamine: Observations mathématiques & physiques, faites dans un voyage du Levant en 1731 & 1732 . In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1732 . Paris 1735, p. 295-322 .

- ↑ Michael Rand Hoare: The Quest for the True Figure of the Earth. Burlington 2005, pp. 1-54, esp. 1-10.

- ↑ Michael Rand Hoare: The Quest for the True Figure of the Earth. Burlington 2005, p. 111 ff.

- ^ Dario A. Lara: L'amitié de deux hommes de science: Charles-Marie de La Condamine et Pedro Vicente Maldonado. Quito 2005.

- ↑ Michael Rand Hoare: The Quest for the True Figure of the Earth. Burlington 2005, pp. 119 ff., 134 ff.

- ^ Charles-Marie de La Condamine: Sur l'arbre du Quinquina. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1738. Paris 1740, pp. 226–243.

- ^ Avraham Ariel, Nora Ariel Berger: Plotting the Globe. Westport 2006, pp. 19-29.

- ↑ Neil Safier: Fruitless Botany: Joseph de Jussieu's South American Odyssey. In: James Delbourgo, Nicholas Dew (Eds.): Science and Empire in the Atlantic World. New York 2008, p. 214.

- ↑ Michael Rand Hoare: The Quest for the True Figure of the Earth. Burlington 2005, pp. 200-205.

- ↑ Urs Bitterli: The discovery of America from Columbus to Alexander von Humboldt. Munich 1991, pp. 269-286.

- ↑ Urs Bitterli: The discovery of America from Columbus to Alexander von Humboldt. Munich 1991.

- ^ Charles-Marie de La Condamine: Relation abrégée d'un voyage fait dans l'intérieur de l'Amérique méridionale. Paris 1745.

- ↑ Maupertuis: La figure de la terre. In: Histoire de l'Académie… 1737. Paris 1740, pp. 389–466.

- ^ Bouguer: Relation abrégée du voyage fait au Pérou. In: Histoire de l'Académie… 1744. Paris 1748, pp. 249–297.

- ↑ Pierre Bouguer: La figure de la terre, déterminée par les observations de Messieurs Bouguer, & de La Condamine,… envoyés par ordre du Roy au Pérou, pour observer aux environs de l'Equateur. Avec une Relation abrégée de ce voyage qui contient la description du pays dans lequel les operations ont été faites. Charles-Antoine Jombert, Paris 1749 ( digitized on Gallica ).

- ↑ Michael Rand Hoare: The Quest for the True Figure of the Earth. Burlington 2005, pp. 203 ff.

- ↑ Family genealogy.

- ^ Nicolas de Condorcet: Éloge de M. de La Condamine. In: Oeuvres de Condorcet. Vol. 2, Paris 1847, pp. 198-199.

- ↑ Florence Greffe: Inventaire La Condamine. ( Memento of the original from October 30, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Paris 2003.

- ^ Trois lettres inédites de Diderot. In: Anne-Marie Chouillet: Recherches sur Diderot et sur l'Encyclopédie. Année 1991, Volume 11, Numéro 11, pp. 8-18.

- ↑ Frank Arthur Kafker: The encyclopedists as worth individuals: a biographical dictionary of the authors of the Encyclopédie. Oxford 1988.

- ^ A b Nicolas de Condorcet: Éloge de M. de La Condamine. In: Oeuvres de Condorcet. Vol. 2, Paris 1847, pp. 201-202.

- ^ Charles-Marie de La Condamine: Mémoire sur l'inoculation de la petite vérole. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1754. Paris 1759, pp. 615–670.

- ^ Charles-Marie de La Condamine: Second mémoire sur l'inoculation de la petite vérole… 1754 à 1758. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1758. Paris 1763, pp. 439–482.

- ^ Charles-Marie de La Condamine: Suite de l'histoire de l'inoculation ... depuis 1758 jusqu'en 1765. Troisième mémoire. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1765. Paris 1768, pp. 505-532.

- ^ Charles-Marie de La Condamine: Histoire de l'inoculation de la petite vérole… Paris 1773.

- ^ Nicolas de Condorcet: Éloge de M. de La Condamine. In: Oeuvres de Condorcet. Vol. 2, Paris 1847, p. 193.

- ^ Charles-Marie de La Condamine et al. a .: Choix des poésies de Pezai, Saint-Péravi et La Condamine. Paris 1810, pp. 277-312.

- ^ Nicolas de Condorcet: Éloge de M. de La Condamine. In: Oeuvres de Condorcet. Vol. 2, Paris 1847, p. 196.

- ^ Charles-Marie de La Condamine: Extrait d'un journal de voyage en Italie. In: Histoire de l'Académie des sciences… 1757. Paris 1762, pp. 336-410.

- ^ Nicolas de Condorcet: Éloge de M. de La Condamine. In: Oeuvres de Condorcet. Vol. 2, Paris 1847, pp. 199-200.

- ^ Johann Jakob Egli : Nomina geographica. Language and factual explanation of 42,000 geographical names of all regions of the world. Friedrich Brandstetter, 2nd edition, Leipzig 1893, p. 520.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | La Condamine, Charles Marie de |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | La Condamine, Charles-Marie de |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French mathematician and astronomer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 28, 1701 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 4, 1774 |

| Place of death | Paris |