Dzierzgoń

| Dzierzgoń | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Poland | |

| Voivodeship : | Pomerania | |

| Powiat : | Sztumski | |

| Gmina : | Dzierzgoń | |

| Area : | 3.88 km² | |

| Geographic location : | 53 ° 55 ' N , 19 ° 21' E | |

| Residents : | 5474 (December 31, 2016) | |

| Postal code : | 82-440 | |

| Telephone code : | (+48) 55 | |

| License plate : | GSZ | |

| Economy and Transport | ||

| Street : | Ext. 515 : Susz - Malbork | |

| Ext. 527 : Dzierzgoń– Morąg - Olsztyn | ||

| Rail route : | PKP - route 222: Małdyty – Malbork (closed) | |

| Next international airport : | Danzig | |

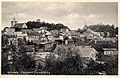

Dzierzgoń [ ˈʥɛʒgɔɲ ] ( German : Christburg , Prussian Grewose ) is a small town in the powiat Sztumski of the Polish Pomeranian Voivodeship . It is the seat of the town-and-country municipality of the same name .

Geographical location

The city is located in the former West Prussia on the river Dzierzgoń (Sorge) , about 23 kilometers southeast of Malbork (Marienburg) and 25 kilometers south of Elbląg (Elbing) .

history

The Prussian name Grewose describes the location of the place at a river point or in a triangular country between rivers. Dzierzgoń is located on and on a moraine hill in a loop of the Dzierzgoń River. In the river valley towards Storchnest ( Mocajny ) and near Baumgarth ( Bągart ) the course of moor bridges from Roman times could be proven, special boarded paths through the Sorgetal, which were already excavated at the end of the 19th century. The facilities were part of the Amber Road , along which the Prussian amber trade with the Roman Empire ran.

Also at the end of the 19th century in the area of today's town-and-country municipality near Baumgarth (Bągart) in the valley of Sorge, a historic sailing boat from the 8th to 11th centuries with a length of approx. 12 m was excavated, previously popularly known as " Viking ship ”. Even if iron nails point to Scandinavian shipbuilding technology, ship finds in the region from this period are scientifically assigned to the Prussian culture.

The Christburg fortress above the river bend was often the focus of the 53-year war of conversion of the Teutonic Order against the Prussians . In 1234 the place was conquered by Heinrich von Meissen , but in 1242 it was regained by the Prussians. Heinrich von Lichtenstein succeeded in taking it again in 1247. Because the castle was taken back by the Prussians, the knights of the order chose the strategically more favorable location on the Schlossberg and founded the new Christburg, a few kilometers away from the old Christburg, above Sorge. Old Christburg was left to the converted and loyal Prussians. The Christburg was burned down during the great uprising.

In 1249, under the mediation of the papal legate Jacob von Lüttich, who later became Pope Urban IV , the Treaty of Christburg was concluded, which as a peace treaty guaranteed the defeated Prussians their freedom if they converted to Christianity and the relationship between the Prussians and the victorious Teutonic Order regulated. The contract also stipulated that a church should be built in Christburg ( novo Christiborc ) by the Prussians.

The city of Christburg was mentioned in a document as early as 1254; In 1288 the use of the Kulm town charter was confirmed. In 1312 Günther von Arnstein gave the place its handicrafts . During the time of the order Christburg was the seat of a commander . The title of Supreme Trappier was associated with his office, who distinguished the Commander of Christburg as one of the five major territorial officers of the order.

Christburg in 1684 (copper engraving by Christoph Hartknoch )

Remains of the ruins of the Ordensburg on the Schlossberg

Foundation walls of the ruins of the Ordensburg , partly bricked up

In the Second Peace of Thorner in 1466 the Teutonic Order lost control of Christburg. The city and its surroundings, referred to in the treaty as opidum et districtus Cristburg alias Drzgon , came under the sovereignty of the Polish crown together with the autonomous Prussian royal portion . In 1492 Nicolaus von Zehmen became burgrave of Stuhm and Christburg. Furthermore, Achatius von Zehmen was Starost on Stuhm and Christburg, where he also lived. In 1517 he became sub-chamberlain of Marienburg, in 1531 castellan of Danzig and in 1546 Woywode of Marienburg. After the Polish Reichstag had denied Achaz I von Zehmen all crown property, his sons, the imperial barons Christoph, Achaz II and Fabian II, stormed the Christburg in December 1576. In return for a settlement of 24,000 florins to be paid to the Kingdom of Poland, the brothers were finally able to keep Christburg.

In 1678 a Franciscan monastery was founded in Christburg. Its buildings were erected on the site of the medieval Heilig-Geist-Spital, destroyed in 1414. Parts of the hospital that have been preserved were integrated into the monastery, for example the gatehouse as the entrance portal and parts of the monastery church, which came from the 13th century. The enclosure north of the church was made from stones from the Ordensburg.

Christoph Hartknoch aptly describes Christburg in 1684 as a town down on the mountain, on top of the mountain he calls a desolate and cursed castle from the orderly , depicted as a ruin on the accompanying engraving. It is also explained that the ghost of a canon haunted the castle, whose death Commander Albrecht von Schwarzburg was said to have caused a curse before the Battle of Tannenberg . The ruin is also said to have been the target of treasure graves in the 17th century.

After the first partition of Poland-Lithuania in 1772, Christburg belonged to the newly created province of West Prussia of the Kingdom of Prussia. From 1818 Christburg was the district Stuhm in marienwerder affiliated. In 1871 the city and Prussia became part of the newly founded German Empire . In 1893, the station south of the city was opened on the Marienburg – Allenstein line.

Due to the provisions of the Versailles Treaty , after the First World War, most of the province of West Prussia had to be ceded to Poland in order to establish the Polish Corridor . In the circle Stuhm east of the province was a referendum conducted in Christburg voted 2,571 inhabitants to remain with East Prussia, Poland accounted for 13 votes. Christburg then remained German and was annexed to East Prussia after the West Prussian Province was dissolved in 1922 .

Towards the end of the Second World War , the city was evacuated on January 22, 1945. The next day, the last refugee train left the city with the military. It was captured by the Red Army on January 24th without a fight. Large parts of the city were burned down after looting and riots against the remaining population. The arcade on the upper, western side of the market , which defines the image of the square, was also affected by the fire .

Soon after, the city was placed under Polish administration. At the same time, the expulsion of the residents who remained in the city began. The city of Christburg was renamed Dzierzgoń . The immigrant Poles initially came mainly from areas east of the Curzon Line .

The destroyed buildings were replaced by new buildings. Around the market, which was still fallow in 1960, residential and commercial buildings were built again. In 1972 the market was renamed Freedom Square.

Demographics

In 1669 there was not a single Catholic in Christburg; in 1742 there were around ten Catholics living here.

| year | Residents | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1772 | 727 | |

| 1776 | 1473 | |

| 1777 | 1377 | |

| 1782 | 1505 | in 266 residential buildings, partly Lutherans , partly Catholics, partly German, partly Polish mother tongue |

| 1793 | 1695 | |

| 1804 | 2104 | Christians, in 233 residential buildings |

| 1816 | 1951 | |

| 1831 | 2183 | |

| 1852 | 2765 | |

| 1864 | 3254 | including 1,974 Evangelicals and 977 Catholics |

| 1871 | 3275 | of which 1,980 Protestants and 980 Catholics (100 Poles ) |

| 1875 | 3303 | |

| 1880 | 3284 | |

| 1890 | 3113 | thereof 2,016 Protestants, 898 Catholics and 193 Jews |

| 1895 | 3218 | 954 Catholics and 167 Jews |

| 1900 | 3116 | mostly Protestants |

| 1925 | 2920 | mostly Protestants (640 Catholics) |

| 1933 | 3366 | |

| 1939 | 3603 |

| year | Residents | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 5638 | As of June 30, 2012 |

politics

City council

The council has 15 members. The President of the Council is Zbigniew Przybysz.

mayor

Elżbieta Domańska has been the mayor of Dzierzgoń since 2014.

coat of arms

The coat of arms shows Catherine of Alexandria with the attributes sword, wheel and martyr's crown on a golden shield. The coat of arms was designed by the German heraldist Otto Hupp in the 19th century based on the images of medieval seals from the 13th century .

Gmina Dzierzgoń

The town-and-country community (gmina miejsko-wiejska) Dzierzgoń includes other localities in addition to the city that gives it its name.

Partner communities

The partner municipalities of Dzierzgoń are:

Culture, sights and sports

Culture and sport

Dzierzgoń has a cultural center with a library. This uses the buildings of the former Franciscan monastery in the city. The municipal sports center, inaugurated in 2012, is located on the same street, directly opposite.

Attractions

Sights in Dzierzgoń are the archaeologically excavated foundation walls of the Ordensburg on the Schlossberg and the nearby Church of the Holy Trinity and St. Catherine. Their history goes back to the 1320s. The originally Gothic building was changed in the course of its history and is now predominantly baroque. At the Sorge the baroque buildings of the former Franciscan monastery are worth seeing. Some elements of the brick Gothic of the former hospital building can still be seen. The Heiliggeistkirche can be found in the monastery complex.

Personalities

- Ernst Schirlitz (1893–1978), German naval officer, most recently vice admiral in World War II and fortress commander of La Rochelle , was born on September 7, 1893 in Christburg.

literature

General

- Christoph Hartknoch : Old and New Prussia. Hallervorden: Frankfurt, Leipzig, Königsberg 1684, pp. 388–389, digitized

- Johann Friedrich Goldbeck : Complete topography of the Kingdom of Prussia. Part II. Marienwerder 1789, pp. 19-20, no. 5.

- August Eduard Preuss : Prussian country and folklore. Königsberg 1835, p. 445, no.60.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Ferdinand Schmitt : History of the Stuhmer circle. Thorn 1868, pp. 179-192.

- Ernst Bahr and Wolfgang La Baume: Christburg. In: Handbook of historical sites , East and West Prussia. Kröner, Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 3-520-31701-X , pp. 27-28.

- Isaac Gottfried Gödtke : Church history of the city of Christburg. In: Archives for patriotic interests. New series, year 1845, Marienwerder 1845, pp. 550–563.

- Felix Hassenstein: Chronicle of the city of Christburg. Kurt Knopp, Christburg 1920.

- Otto Piepkorn: The home chronicle of the West Prussian city of Christburg and the country on the Sorge river. Bösmann, Detmold 1962.

Literature on the Ordensburg

- Małgorzata Jackiewicz-Garniec, Mirosław Garniec: Castles in the Teutonic Order State of Prussia: Pomesanien, Oberland, Warmia, Masuria , translated from Polish: Mirjam Jahr, Studio ARTA, Olsztyn 2009, ISBN 978-83-912840-6-3 , p. 116-126

Literature in Polish

- Mieczysław Kazimierz Korczowski: Dzieje Dzierzgonia: od X wieku do 1990 roku , Rada Miejska, Dzierzgoń 2006, ISBN 978-83-910173-1-9

- Janusz Namenanik: Dzierzgoń: szkice z dziejów miasta , CeDeWu, Warszawa 2013, ISBN 978-83-7556-585-0

Web links

- Miejski portal internetowy (City Internet Portal), Gmina Dzierzgoń (Polish)

- Christburg , Landsmannschaft West Prussia eV, home district Stuhm

Individual evidence

- ^ Hugo Conwentz: The moor bridges in the valley of concern on the border between West Prussia and East Prussia. A contribution to the knowledge d. Natural history u. Pre. d. Country. Bertling, Danzig 1897, digitized

- ↑ Maria Budzinska: Historia Dzierzgonia. Gmina Dzierzgoń, accessed on May 28, 2016 (Polish).

- ^ Hugo Conwentz: The moor bridges in the valley of concern on the border between West Prussia and East Prussia. A contribution to the knowledge d. Natural history u. Pre. d. Country. Bertling, Danzig 1897, p. 129, digitized

- ↑ a b c Otto Piepkorn, 1962, see literature

- ↑ Johannes Hoops (Ed.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Volume 4. 1st edition. KJ Trübner, Strasbourg 1918–1919. Plate 15 - Fig. 17 u. P. 107.

- ↑ Maik-Jens Springmann: The early shipbuilding and shipping in Kur- and Prussenland. In: Praeities puslapiai: archeologija, kultūra, visuomenė. Skiriama archeologo prof. habil. dr. Vlado Žulkaus 60-ties metų jubiliejui ir 30-ties mokslinės veiklos sukakčiai. Universiteto Leidykla, Klaipėda 2005, pp. 145–189.

- ↑ Samuel Ed. And JG Gruber (Ed.): General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts. Volume 17. Leipzig 1828, pp. 66-67.

- ^ A b c East Prussia and West Prussia (= Hartmut Bookmann: German History in Eastern Europe ). Siedler, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-88680-212-4

- ↑ Christburg Treaty 1249 , Herder Institute for Historical Research on East Central Europe, Marburg, accessed on May 25, 2016

- ^ Heinrich Gottfried Philipp Gengler : Regesta and documents on the constitutional and legal history of German cities in the Middle Ages. Erlangen 1863, pp. 490-491

- ^ Treaty of Thorn 1466 , Herder Institute for Historical Research on East Central Europe, Marburg, accessed: May 25, 2016

- ↑ Christoph Hartknoch: Old and New Prussia . 1684, p. 388 .

- ↑ Herbert Marzian , Csaba Kenez : Self-determination for East Germany - A documentation on the 50th anniversary of the East and West Prussian referendum on July 11, 1920. Editor: Göttinger Arbeitskreis , 1970, p. 124

- ^ Friedrich Wilhelm Ferdinand Schmitt : History of the Stuhmer circle. Thorn 1868, p. 189.

- ↑ a b c d Friedrich Wilhelm Ferdinand Schmitt : History of the Stuhmer circle. Thorn 1868, p. 188.

- ^ Johann Friedrich Goldbeck : Complete topography of the Kingdom of Prussia. Part II: Topography of West Prussia. Marienwerder 1789, pp. 19-20.

- ^ Handbook of Historic Places , East and West Prussia. Kröner, Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 3-520-31701-X , pp. 27-28.

- ↑ Alexander August Mützell, Leopold Krug : New topographical-statistical-geographical dictionary of the Prussian state. Volume 1: AF. Halle 1821, p. 229, item 254.

- ^ August Eduard Preuss : Prussian country and folklore. Königsberg 1835, p. 445, no.60.

- ^ Topographical-statistical manual of the Prussian state (Kraatz, ed.). Berlin 1865, p. 95 .

- ^ E. Jacobson: Topographical-statistical manual for the administrative district Marienwerder. Danzig 1868. Register of localities in the Marienwerder administrative district , pp. 196–197, no. 24.

- ^ Gustav Neumann: Geography of the Prussian State. Volume 2. 2nd edition. Berlin 1874, pp. 47-48.

- ↑ a b c d e Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. Landkreis Stuhm (Polish Sztum). (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).

- ^ Brockhaus' Konversations-Lexikon. 14th edition, Volume 4, Berlin and Vienna 1998, p. 272.

- ^ Meyer's Large Conversational Lexicon. 6th edition, Volume 4, Leipzig and Vienna 1908, p. 102.

- ↑ The Big Brockhaus. 15th edition, Volume 4, Leipzig 1929, pp. 96-97.

- ↑ http://www.stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/l_ludnosc_stan_struktura_30062012.pdf

- ↑ Herb Dzierzgonia. Gmina Dzierzgoń, accessed on May 25, 2016 (Polish).