Main building of the RWTH Aachen

The main building of the RWTH Aachen is the house Templergraben 55 in Aachen and the seat of the administration of the Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule .

history

founding

The founding of the Polytechnic School in Aachen goes back to a donation from the Aachen and Munich fire insurance companies to Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm . After completing his honeymoon with Princess Victoria of Great Britain and Ireland near Herbesthal, he had returned to German soil and was received there on February 4, 1858 by the representatives of the Rhine Province. The citizens of Aachen gave a reception for the couple in the town hall. On this occasion, the District President Kühlwetter presented the Crown Prince on behalf of the Aachener und Münchener Feuerversicherungsgesellschaft founded by David Hansemann in 1825 with a gift of 5000 thalers , which he wanted to use to promote a polytechnic school in the Rhineland based on the model of the École polytechnique in Paris. After five years of discussion about the location and offers of the cities of Cologne , Aachen , Düsseldorf and Koblenz , which had applied for it, Aachen was chosen on November 14, 1863. This decision was made easier by the fact that the Aachen industrialists and especially the Aachen and Munich fire insurance company with their subsidiary, the Aachen Association for the Promotion of Labor , were prepared to invest enormous sums in the project 'Polytechnic School'. While Cologne hesitated to take over the school fees, Aachen provided the property and a construction subsidy of around 200,000 thalers. The Prussian state itself only wanted to cover about a quarter of the estimated operating costs of 40,000 thalers.

For Aachen as the location of a polytechnic school, the industry that had spread in and around Aachen spoke above all. Cologne, on the other hand, was more like a commercial than an industrial city.

After Aachen was determined, there were further discussions about the location within Aachen. The choice was between the property on the north side of the Templergraben, owned by the Poor Administration, and one in today's Rehmviertel, between Cologne and Adalbertstor, which belonged to the major Aachen entrepreneur Gerhard Rehm . On August 20, 1864, the Aachen government informed the Minister of Commerce, Count von Itzenplitz, of the decision in favor of the property at Templerbend, which he then approved as a building site on September 19. The property was 3 2/3 acres , i.e. about 11,000 m², and was located between the Templergraben and the former Templerbend train station, which was relocated to Aachen-West in 1905 in order to expand the university .

construction

The main building of the RWTH Aachen was built between 1865 and 1870. The architect and site manager was Robert Ferdinand Cremer (1826–1882). His father, the so-called "Schinkel Aachens", built the theater , the Elisenbrunnen and the old government building , which today houses the historical institute and the university archive of RWTH Aachen University . At that time Cremer was a building inspector in Aachen and was entrusted with the restoration of the Aachen minster . On February 9, 1864, the Berlin Minister of Commerce, Graf von Itzenplitz, based on the proposal of the Aachen District President Friedrich Kühlwetter, awarded the building contract for the polytechnic school to Cremer, who immediately went on a study trip to other polytechnic schools in order to be inspired by their buildings. After visiting the polytechnics in Karlsruhe , Stuttgart , Hanover and Zurich , among others , he submitted two drafts to the Ministry of Commerce in Berlin on November 2, 1864. The first design preferred by Aachen's district president, Kühlwetter, was a building in Gothic style, the other one in Italian.

Indeed, the similarity of the main building in Aachen to the main buildings of the universities in Stuttgart , Dresden and Zurich cannot be denied. The first thing that was erected was the polytechnic school on Antonsplatz in Dresden. Prof. Gustav Heine, teacher for architecture at the technical educational institute, was commissioned with the design. Due to disputes with the expert, Prof. Sänger, a new expert was called in, Professor Gottfried Semper from Zurich . The building, which opened on September 8, 1846, is a version of Heine's design revised by Semper. 12 years later, Semper won an architectural competition to design the new main building for the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. It was completed in 1864. At the same time the construction of the main building of the Polytechnic School in Stuttgart was completed. The architect was Joseph von Egle .

On April 28, 1865, the Berlin Ministry decided in favor of the Italian-style building. An unofficial laying of the foundation stone already took place on May 5th, which was solemnly repeated on May 15th in the presence of King Wilhelm I and at which the architect Robert Cremer was awarded the title of building officer. On the same day, the 50th anniversary of the Rhineland to Prussia was celebrated, which was originally supposed to take place in Cologne, but was moved to Aachen due to the current occasion of the laying of the foundation stone.

Building description

In 1868 the main building was completed. Cremer originally planned a large structure with an extensive inner courtyard, but then decided on a horseshoe-shaped, three-winged complex, which was to be supplemented by a transverse wing at the rear. The transverse tract was built slightly offset from the main building so that the inner courtyard can be accessed.

The main building is made of brick, which is clad with natural stone on the front. The natural stones are all of Rhenish origin: the base is made of Drachenfels trachyte from the Siebengebirge , the rear part is made of basalt lava . This is followed by red Trier sandstone, the upper floors are made of tuff from the Eifel , from the municipality of Brohl . The change in material resulted in a remarkable color change that can still be admired today.

The main building was able to retain its external appearance over the years. It is three-story and built on a high basement. The four corners are accentuated by risalits , as is the main entrance with the outside staircase on the Templergraben by a central risalit. The individual floors are separated by strong cornices, which, together with the parapet of pillars and balusters surrounding all the front sides, ensure a strong horizontal emphasis. The high, closely lined up arched windows, together with the risalits, counteract this horizontal emphasis, which achieves the balance typical of classicism . There were originally five figures on the attic of the central risalit, but they were lost after the Second World War. The corner crowns of the side elevations in the form of eagles, which were subsequently ordered by the royal government, are still standing today. The courtyard side of the building was left in brickwork.

The rear transverse tract of the main building was an unplastered brick building, formerly three-storey, 15-axis and provided with two side projections. In 1910 a part was demolished to make room for a power station. In the Second World War, the building was then further reduced to a remainder of seven axes due to damage, which is now called the "ivy house" and provides shelter for part of the administration.

In the transverse tract behind the main building were the rooms for theoretical and technical chemistry and the iron and steel industry, in the main building the auditorium, administration, castellan's apartment and workshops, as well as the remaining disciplines: architecture (I), construction and engineering (II), machine and Engineering, General Sciences (Mathematics and Natural Sciences) (V).

The school was initially intended for 500 students. As early as 1875, 450 students attended the Aachen Polytechnic. In 1872/73 two drawing rooms, several professors' rooms and collection rooms had to be created by adding an extension to the main staircase, after a false ceiling had previously been drawn through the representative auditorium due to a lack of space and it was also converted into a drawing room.

Memorial plaque in honor of those who fell in World War I.

In the main staircase, at the end of the first flight of stairs, already visible from below, is the representative auditorium of the RWTH, which bears the name of its founder, the Aachener und Münchener Versicherung. The auditorium was built with the help of a donation since 1939 and inaugurated in October 1940. Lectures, festive events, awarding of honorary degrees and public lecture series are held here.

A memorial plaque with a list of names engraved in marble at the entrance to the auditorium reminds of around 170 fallen soldiers from the First World War , as can be deduced from the attached death dates (only in the period 1914–1918). Above it is the motto in gold-colored capital letters: "When it was true for the fatherland, faithfully the blade was at hand, but it was the last step". The verse is based on the 3rd stanza of the student song Guys Out! (known since 1844), which says:

"Guys out! Let it ring from house to house!

If it's for the fatherland,

keep the blade at hand, and out with a courageous song, it would also be the last step!

Guys out! "

Since then, this shout “boys out!” Has been used in many patriotic appeals to the Franco-German War of 1870/71 and the First World War; so also in the appeal of the then rector of the TH Aachen, Adolf Wallichs , in the echo of the present on August 1, 1914:

"Fellow students!

In a difficult hour, the king calls the people to arms in defense of their beloved fatherland. We answer this call with enthusiasm!

Guys out! When it comes to the fatherland, keep your blades at hand! if you have sung so often, quickly put this vow into action! [...] "

This makes the statement of the memorial plaque's motto, which is no longer in the subjunctive but in the past tense, unequivocal: the boys listed, probably students, were there when it was a matter of fighting for the fatherland; however, it was her last walk; that is, they fell in their duty to the fatherland.

The memorial plaque was ceremonially unveiled on July 2, 1925. On the following day the “Politische Tagesblatt” printed the address for the inauguration of the then Rector Bonin. In this he remembered the dead, "they died for Germany's happiness". The board stands in the context of the RWTH's culture of remembrance : As early as 1918, the rector asked the families of the fallen students to send pictures of their deceased sons to RWTH, as they wanted to create an album of the students who died in the war.

Protests against the plaque

This archaic-militaristic form of commemorating those who died in war and the assumption that the plaques were created and set up during National Socialism have led to repeated protests from students since 1989.

When the first arguments about the memorial plaque at the entrance to the Aachen and Munich auditoriums broke out in 1989, it was still unclear exactly when the memorial was made and erected. As the assembly hall was known to have been built between 1939 and 1940, it made sense to place the memorial plaque in this time as well. A leaflet from the MAI (mechanical engineering initiative; group in the mechanical engineering student council) states: “The Aachen Munich hall was built between September 1939 and 1940, when the university was closed due to the outbreak of war. It was during this time that the plates were probably placed at the entrance. ”At the initiative of the MAI, a letter was passed in the student parliament on May 10, 1989, which was sent to Rector Klaus Habetha . It says:

“Dear Mr. Habetha,

the repair work on the heroes' memorial plaques at the entrance to the auditorium has led to discussions among students since the beginning of the year.

We believe that this monument should be removed as soon as possible. Such a glorification of heroic death and war cannot be reconciled with the principles of a peaceful and democratic society. [...] "

Furthermore, the letter calls for a new memorial, which "commemorates the crimes of National Socialist Germany" and is dedicated to those "who suffered and were murdered because of the culpable involvement of individual university members and RWTH as an institution."

There were also dissenting voices from students and supporters of the plaque, such as representatives of the RCDS, a group in the student parliament. In their opinion, the fallen of the First World War would be trampled underfoot and the attempts to abolish the honor plaques were "smoothing out history". According to Phil-fold No. 8/89, the history professor Johannes Erger (focus: recent history and contemporary history), who saw the demands of the plenary assemblies and the student parliament as a renewed attempt, expressed his rejection of the student's request to demolish the memorial plaque , " rewrite history in retrospect ”.

In the Senate meeting on June 1, 1989, the letter from the student parliament was addressed by one of the student election senators, Martin Debener. The rector then announced that the rectorate had discussed the request and came to the opinion not to remove the existing memorial plaques. He argued, among other things, that the plaque does not show hero worship. In addition, one should not so lightly remove such certificates from the history of the local university. These memorial plaques would reflect the opinion of the university members at the time. Furthermore, Rector Habetha addressed the consideration at this meeting whether the victims of National Socialism could not be commemorated in the same way. Even if the funds were not available at the moment, Habetha promised that the rectorate would tackle the matter and also discuss a memorial plaque for the victims of war and violence.

In the course of the conversation, Markus Große-Ophoff, another student representative, stated that he did not criticize the memorial plaques as such, but that the saying above the list of names (see above) was "very combative and glorified the death of a hero". Habetha replied that this could be interpreted as such, but that opinion was divided. It should not be forgotten that during the First World War, many young people went to war with great enthusiasm to defend their fatherland. But the disillusionment occurred just as quickly.

Next, the student electoral senator Ralf Demmer spoke, who took one position per plaque. First of all, he reported on the heated discussions during the penultimate session of the student parliament, at which two points of view emerged: Some (21 votes) had pleaded for the removal, as the boards were made in National Socialist Germany and expressed a glorification of the heroic death. The other (20 votes) would have spoken out in favor of retaining it. He himself was of the opinion that one could not see a glorification of National Socialism in the memorial plaques, since they were victims of the First World War. However, Demmer suggested a notice board that would show when this board was erected and for what purpose. He also explains that one should not, in retrospect, obliterate all traces of that time from what is now a very extreme understanding of the time. The historical events, as they happened then, have to be allowed to work for you, even from today's perspective. In no case should one make subsequent changes or falsifications of history.

In the course of the next few months there was apparently a compromise solution according to which a second memorial, commenting on or integrating the memorial plaques, was to be erected at the entrance to the auditorium in honor of the victims of the Holocaust . A special commission was set up to redesign the panels and an architect was asked for corresponding designs. The discussions about changing the memorial at the entrance to the auditorium were ended in December 1990 by Rector Habetha. In the Senate meeting on December 6th, the latter declared that the special commission had agreed to use the memorial plaque made in the period after the First World War and made for the victims of the First World War as a memorial from this time. He also referred to the discovery of a student member of the special commission: In 1953, the university donated a statue to commemorate the victims of the Second World War. This is the "crying youth" that is displayed in the RWTH student village today .

In 1991, the effect of the memorial plaques was indirectly criticized again when students from the teaching department at vocational schools in connection with protests against the Gulf War put a new text above the plaque: "Death is a master from Germany" was up for a few hours reading a poster. During these days, among other things, arms research at RWTH was also a topic.

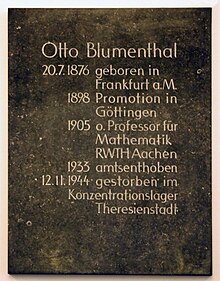

Four years later, Hermann-Josef Diepers, at that time a member of the mathematics / physics / computer science department, dealt in detail with the history of its origins and the disputes surrounding the memorial plaque. His essay was published in a collection that was published by a group of left-wing students on the occasion of the 125th anniversary of the RWTH in order to "critically examine" it. Diepers lists a number of pieces of evidence for an ongoing militaristic, national to nationalistic policy, the opposition to the Weimar Constitution , the Versailles Peace Treaty and the university administration's denial of war guilt. Accusingly, he states: “The previous memorials are those for perpetrators. The university and most of its members saw themselves as conscious instruments of a war policy. The abuse with the slain is the education for militarism and the use of this spirit, for which the TH management and the student representatives are to blame. "Although he was able to prove that the boards had not been erected by the National Socialists (see below for the history of origin) , but nevertheless, in his opinion, he was able to demonstrate militaristic ideology to the RWTH, the rectorate and students of the corporations. Finally, he directed the question “to the address of RWTH [...] how long it will remember the perpetrator and describe this as commemoration of the victim. A worthy memorial should be given to those who opposed the inhuman war policy (not only of the National Socialists) and were also persecuted within the TH, as the example of Professors Alfred Meusel and Otto Blumenthal shows. The boards in the auditorium should be removed! "

Diepers' demands initially remained without a response. In October 2008, however, the Kármán , RWTH's student newspaper, took up Dieper's thoughts again. The article makes it clear that for the viewer of the (uncommented) memorial plaque at the entrance to Aula I in the main building, questions must remain open and that misunderstandings can occur again and again. The authors propose a comment next to the board: “It would justify the board as a historical document and clearly place it in the correct historical context. Otherwise, the question remains whether the RWTH has no other "heroes" to offer than the war dead? "

The article triggered an exhibition on the main building initiated by the Rectorate, which the RWTH University Archives opened on June 8, 2009.

Up until the 1990s there was still some uncertainty about when exactly the plaque was created and placed. Was it created during National Socialism, inaugurated in 1940 together with the Aachen and Munich halls, and did it therefore serve National Socialist war propaganda purposes ? The discussions of 1989/90 evidently started from this assumption. In the above-mentioned Senate meeting on December 30, 1990, Habetha spoke of the fact that the plaque was created in the period after the First World War, but there was no precise evidence at that time. It was only Diepers' research that led to the clear result that the memorial plaque must have existed as early as the early 1920s. The main source for the history of its origins is file 584 from the RWTH Aachen University Archives.

The main building during World War II and in the post-war period

When the Second World War broke out on September 1, 1939, German universities were temporarily closed. Although the RWTH was the last of the German universities to reopen in the winter semester 1940/41, normal teaching in the faculties was out of the question in times of war. While 821 students studied in Aachen in 1938/39, there were only 255 in 1940/41.

Thanks to a generous donation from the Aachener und Münchener Feuerversicherungsgesellschaft, which gave the impetus for the establishment of the Polytechnic School with a donation as early as 1858, a new auditorium was built in the main building, which was inaugurated in 1940.

Air raids worsened the situation for the university from 1941; on June 10, the building that housed the library was badly damaged. Nevertheless, the Reich Ministry of Education instructed in a circular of March 26, 1943 that teaching was to be continued in principle in all academic universities despite the war situation. But heavy bombing raids on the Westbahnhof and the adjoining university campus in May 1944 and street fighting in September and October 1944 made the situation increasingly worse. At the end of the war, up to 70% of the campus was destroyed. In particular, the main building, the chemical technology building behind the main building and the chemical laboratory fell victim to the direct bombing hits. The main facade of the main building was missing and the auditorium, inaugurated in 1940, was badly damaged in 1944.

Despite this structural damage, the university was reopened on January 3, 1946, after at least the worst damage had been poorly repaired; so the assembly hall was at best provisionally repaired by 1947. In the summer semester of 1946, teaching and research in all faculties began again.

By 1951 the structural damage had been reduced to 25%. With a construction budget of DM 70,892,000, the war damage to RWTH Aachen University was repaired between 1949 and 1958.

Interior decoration and the statues on the attic

When entering the main building in the 19th century, one came into the vestibule equipped with columns. The walls and ceilings were kept in strong, bright colors, also in the stairwell and in the auditorium. The original wall painting reappeared during renovation work and was reconstructed in the corridor behind the vestibule and can be viewed again today. Immediately behind this corridor the main staircase led to the first floor, where originally the two-story auditorium was located above the vestibule. The stairwell was also painted in strong colors.

Statues in the stairwell

If you went up the stairs until 1872, you could see, next to marble busts of His Majesty the King and the Crown Prince, on the left and right side, framed in round arches, seven statues.

Ferdinand Esser wrote in 1871: “The staircase [...] was decorated with the most important statues of ancient classical art, such as those of Apollo Belvédère, Minerva, Niobide, Antinous, Diana of Versailles etc., in addition to the wall niches being decorated all are suitable and determined to have a stimulating effect on the education of the polytechnicians visiting the institute, also in artistic terms, a very dignified ornament and ornament in the life-size marble busts of the king and the crown prince. "

There were three figures on the left; left Apollo of Belvédère , in the middle the goddess Minerva and right Antinous . The statue of Apollo Belvédère shows the Greek god Apollo, who not only stands for light, but also for the arts, especially for music, poetry and song. The Roman goddess Minerva, equated with Athena in Greece , is not only the goddess of warfare, but also of wisdom and art, especially poets and teachers. She is the guardian of knowledge.

The sculpture on the right represents Hadrian's lover, Antinous. The Antinous type was an extremely popular example of ancient art in the 19th century.

There were four statues on the right side of the stairwell. According to Ferdinand Esser, the figure on the left could be a Niobide . The Greek tragedy poet Sophocles (Lateran type) was depicted to the right.

Diana of Versailles represents the Roman goddess Diana or the Greek Artemis . Diana is the sister of Apollo, goddess of the hunt, of fertility and the protector of women, girls and youth.

The final figure was Hermes , god of poetry.

Auditorium

The walls of the original auditorium from 1870, which lay above the vestibule and comprised two floors (12.24 m), were brightly painted like those of the entrance hall and the stairwell. The medallions of the most important "German scholars and technologists whose work was related to polytechnical science" hung in double rows in the round arch of the aisle-side false window, the frames of which were tiered several times and surrounded by rods of pearls. The following heads were depicted in the auditorium:

- Leopold von Buch (* 1774; † 1853) - geologist (one of the most important representatives of his field in the 19th century)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (* 1769; † 1859) - natural scientist and co-founder of geography as an empirical science

- Martin Heinrich Klaproth (* 1743; † 1817) - chemist

- Eilhard Mitscherlich (* 1794; † 1863) - chemist and mineralogist

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (* 1646; † 1716) - philosopher and scientist, mathematician, diplomat, physicist, historian, politician, librarian and doctor of secular and canon law

- Johann Carl Friedrich Gauß (* 1777; † 1855) - mathematician, astronomer, geodesist and physicist

- Ferdinand Jakob Redtenbacher (* 1809; † 1863) - founder of scientific mechanical engineering

- Johann Friedrich August Borsig (* 1804; † 1854) - mechanical engineer, entrepreneur and the founder of the Borsigwerke

- Gotthilf Heinrich Ludwig Hagen (* 1797; † 1884) - engineer, specializing in hydraulic engineering

- Ernst Heinrich Carl von Dechen (* 1800; † 1889) - Professor of Mining Studies

- Christian Peter Wilhelm Friedrich Beuth (* 1781; † 1853) - "Father of Prussian Business Development". Through a series of suitable measures - the founding of clubs and schools, technology transfer from abroad, templates for the aesthetic design of industrial products and others - he paved the way for Prussian producers from manufacturing to competitive industrial production

- Abraham Gottlob Werner (* 1749; † 1817 Dresden) - mineralogist; is considered the founder of geognosy

- Justus von Liebig (* 1803; † 1873) - chemist

- Robert Wilhelm Eberhard Bunsen (* 1811; † 1899) - chemist

- Heinrich Wilhelm Dove (* 1803; † 1879) - physicist and meteorologist

- Heinrich Gustav Magnus (* 1802; † 1870) - physicist and chemist

- Karl Karmarsch (* 1803; † 1879) - technologist and for many years the first director of the Polytechnic School, which later became the Technical University in Hanover

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (* 1784; † 1846) - astronomer, mathematician and geodesist; one of the most famous German scientists of the 19th century

- Karl Friedrich Schinkel (* 1781; † 1841) - founder of the Schinkel School; Prussian architect, master builder, town planner and painter who decisively shaped classicism in Prussia

- Friedrich Albert Immanuel Mellin (* 1796; † 1859) - architect and general building director

The "praying boy"

The statue of the “praying boy” in the foyer of the main building is a reconstruction of a life-size bronze statue from the 3rd century BC. The original is in the Altes Museum in Berlin. Archaeologists and engineers at the foundry institute of the RWTH were interested in the work processes in the ancient workshops and the manufacturing techniques of bronze statues. In particular, the simulation process newly developed at RWTH Aachen University became the key to the new knowledge about the flow and solidification behavior of molten metal. In this context, the smaller statue now in the main building vestibule was cast. The “praying boy” has thus built a bridge between the humanities and natural sciences.

Statues on the attic

There were once five statues on the attic of the main building. Unfortunately, these were destroyed or removed during World War II. Only the “Program of the Royal Rhenish-Westphalian Polytechnic School in Aachen for the course 1870 | 71” and the construction plans contain information about them. The figures were described as follows: “The city of Aachen with the distaff, the Rhine province with urn and grapes, in the middle Minerva with the Prussian eagle and next to it two owls as acroteries, the province of Westphalia with oak leaves and coat of arms, Borussia with armor and spear . "

Standing in front of the main building, one found from left to right: the allegorical figures, each nine feet tall , the city of Aachen and the Rhine Province , in the middle the 15 foot tall Minerva, who one met in the stairwell and again two nine-foot personifications of Westphalia and Prussia . The latter, Borussia, is shown more simply than its image on the Victory Column in Berlin.

Willy Weyres , Professor of Building History and Monument Preservation at RWTH Aachen University, speaks of "[...] larger than life [n] figures of science [...] accompanying the mighty figure of Pallas Athene in the middle." Miriam Wolf, on the other hand, interprets the statues as Show of power by the Prussian state.

On the iconography of the building

The iconography of the building is shaped by the many references to antiquity . The choice of the Italian Renaissance instead of the neo-Gothic for the architectural design connects the technical university with the educational awakening of the Renaissance and the rediscovery of ancient education. Next door, at the chemical laboratory, was emblazoned with the saying Mens agitat molem (the spirit moves matter), which goes back to Virgil ( Aeneis VI, 727 ). These reminiscences and allusions to antiquity represented a bow by the Technical University to the classical humanistic ideal of education, the essential roots of which were seen in antiquity. One wanted to place oneself in the ranks of the traditional universities . At the same time, the "gallery of ancestors" installed in the auditorium showed the self-confidence of the technical university of great technicians.

See also

literature

- Ferdinand Esser: The polytechnic school in Aachen . In: Journal of Construction . Volume 21, 1871, Col. 5–20 ( digital copy [PDF; 37.8 MB]).

- Paul Gast : The Technical University of Aachen 1870–1920. A memorial . Aachen 1921.

- Herwart Opitz : The development of the Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen from 1949-1959 . Aachen 1959.

- Herbert Philipp Schmitz: Robert Cremer 1826–1882. Builder of the Technical University and restorer of the cathedral in Aachen . Publishing house Aachener Geschichtsverein , Aachen 1969 ( Aachener contributions for building history and local art . Volume 5).

- Hans Martin Klinkenberg (Ed.): Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen 1870–1970 . O. Bek Verlag, Stuttgart 1970.

- Kurt Düwell : The establishment of the Royal Polytechnic School in Aachen. A section of Prussian school and university history in a town on the Rhine . In: Journal of the Aachen History Association . 81, pp. 173-212 (1971).

- Willy Weyres : The Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule in Aachen . In: Eduard Trier (Ed.): Art of the 19th century in the Rhineland. Profane buildings and urban planning . Volume 2, Düsseldorf 1980.

- Ingeborg Schild , Reinhard Dauber : Buildings of the Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen (= Rheinische Kunststätten . Issue 400). Neuss 1994.

- Hermann-Josef Diepers: "It is sweet and honorable to die for the fatherland" . In: OASE e. V. (Ed.): "... far removed from all politics ...". RWTH - a reader . Aachen 1995, pp. 81-97.

- Klaus Ricking: The spirit moves matter - Mens agitat molem. 125 years of RWTH Aachen history . Wissenschaftsverlag Mainz, Mainz 1995, ISBN 978-3-930911-99-8 ( digitized version ).

- Roland Rappmann: The beginnings of RWTH Aachen University in pictures and documents. Exhibitions in the university library on the occasion of the 125th anniversary of the Technical University of Aachen . Aachen 1996.

- Miriam Wolf: The main building of the RWTH Aachen. An architectural historical analysis . Aachen 2007 ( digitized version ).

Web links

- Entry on the main building of RWTH Aache in the database " KuLaDig " of the Rhineland Regional Association

- Information on the history and founding of the RWTH on the website of the university archive [not available: May 29, 2017]

Remarks

- ↑ Arthur Weichold: The destroyed historical buildings of the Technical University of Dresden . In: Kurt Koloc (ed.): 125 years of the Dresden University of Technology. Festschrift . Berlin 1953, p. 241.

- ↑ See the commemorative publication The Jubilation Celebration of the Union of the Rhineland with the Crown of Prussia .

- ↑ Complete copy of the names on denkmalprojekt.org , accessed on May 29, 2017.

- ↑ Hermann-Josef Diepers: "It is sweet and honorable to die for the fatherland" . In: OASE e. V. (Ed.): "... far removed from all politics ...". RWTH - a reader . Aachen 1995, pp. 81-97, here: p. 88.

- ↑ For information on RWTH during the First World War, see the online presentation First World War on the pages of the university archive. There, the names of the fallen students are provided on the memorial plaque with links to biographical information or to the photographs preserved in the university archive. For the culture of remembrance of the connections see the note from Johanna Zigan: The First World War. Catalyst for the acceptance of engineering sciences using the example of RWTH Aachen . Master's thesis Aachen 2007, p. 78 ( digital copy [PDF; 3.3 MB]).

- ↑ Hermann-Josef Diepers: "It is sweet and honorable to die for the fatherland" . P. 82.

- ↑ Hermann-Josef Diepers: "It is sweet and honorable to die for the fatherland" . P. 81f.

- ↑ Hermann-Josef Diepers: "It is sweet and honorable to die for the fatherland" . P. 81f.

- ↑ For the following discussion in this Senate meeting, see the minutes of the Senate meeting on June 1, 1989 in: Hochschularchiv, File 11139, pp. 26–31.

- ↑ Cf. the address by Walten Eilender of July 27, 1953 on the occasion of the handover of the memorial (sculptor Akkermann) for the students of the TH who died in the two world wars in: Hochschularchiv, file 1189.

- ↑ Hermann-Josef Diepers: "It is sweet and honorable to die for the fatherland" . P. 96.

- ↑ Hermann-Josef Diepers: "It is sweet and honorable to die for the fatherland" . P. 97.

- ↑ Helen Rabenau, Till Spieker: "When it was true for the fatherland the blade was at hand but it was to the last gear". Why the saying above Aula I is problematic . In: Kármán of October 29, 2008.

- ^ Ferdinand Esser: The polytechnic school in Aachen . In: Journal of Construction . 21st year, 1871, p. 12.

Coordinates: 50 ° 46 ′ 39.6 " N , 6 ° 4 ′ 40.7" E