Holy grave (Speyer)

The Holy grave Speyer (probably (due to the characteristic of the Templars design Templar rotunda) and "the Knights Templar Church") was one in Speyer suburban Old Speyer nearby church, which after 1148 by two rich Speyerer citizens as a structural replica of the Holy Sepulcher to Jerusalem built has been.

history

Rise of the monastery

At Christmas 1148, Bernhard von Clairvaux called King Konrad III in a speech in the Speyer Cathedral . and to march the princes, knights and squires present to the Holy Land. Around the same time, two wealthy Speyer citizens went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to visit the tomb of Jesus Christ . After their return, out of gratitude for the successful pilgrimage, they began to build a “church and burial place based on the model of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem” on Diebsbrücke in the far north of the suburb of Altspeyer. In addition to the church, they also founded a convent for women, which took over the completion of the church after their death. The church is reported to have attracted large numbers of visitors even before its completion. After its completion the pilgrims came and testified that the church in Speyer was exactly like that in Jerusalem. Apparently the nuns were doing very badly, with the result that the buildings fell into disrepair and the foundation's income fell. Therefore, the Speyer bishop Konrad III. With the approval of the cathedral chapter and the citizenship in 1207, the monastery and its possessions were transferred to the monastery of the Brothers of the Holy Sepulcher in Denkendorf near Stuttgart . In return, the local provost Konrad had to take care of the nuns and, after their death or resettlement, was allowed to found a "Convention of the Brothers of the Holy Sepulcher " in the former nunnery , which was under the control of the Speyer bishop. This convention received extensive grants shortly after its establishment. So were the brothers in 1214 by King Friedrich II. The rights of patronage to Kirchheimbolanden with the associated decade and the villages Bischheim, Morschheim, Rittersheim, Orbis and Altenbolanden. Because of this donation, the priest for the parish there came from among the brothers. In 1228 the brothers were exempted from taxes, duties and services by Emperor Friedrich.

1335 gave counts of Sponheim an already existing within the Celtic ring wall on the Donnerberg preferred James Chapel the Prior Heinrich from Saint grave convent Speyer to where a "real Kloster" from Eremiten order of St. Paul ( Pauliner to start). The chapel was attached to the parish of Kirchheimbolanden, which belonged to the Speyer convent, and in 1371 was ceded to the Pauline hermits who founded the St. Jakob monastery there .

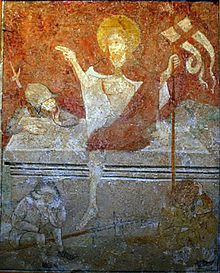

In 1295, Count Rudolf von Neuffen gave the Speyer Holy Sepulcher Monastery church patronage in Güglingen , which was ceded to Württemberg in 1541. The very old Marienkirche Eibensbach belonged to the parish of Güglingen , where the monastery founded a chaplain in 1457. Around the same time this church was painted. Among other things, a splendid image of the Holy Sepulcher with the risen Jesus sitting on it has been preserved. It should have been made on behalf of the Speyer Holy Sepulcher Monastery and corresponds to the image that was to be found on its seal.

From 1449 until the Reformation, the monastery also owned the church set for the parish of Gundelsheim as a gift from Count Ludwig I of Württemberg .

Consequences of the Reformation

The prior Nikolaus Speicher converted to Protestantism with the three other brothers in 1565, to the delight of the city council. This met with displeasure with the Speyer Bishop Marquard , so that the monastery was visited on January 14, 1567 by the vicar general of Bishop Stephan Rumelius and a notary. As a result, two brothers said they had been seduced by the prior and renounced Protestantism. Only the prior insisted on his change. In order to remove the prior of his office, the bishop wrote to Cardinal Otto zu Augsburg , who appealed to the Pope for his removal from office. In 1574 Johann Lucae became prior of the convent.

Decline of the monastery

In 1585 the provost of Denkendorf sold the convent and the associated goods to the city, which used it as a hospital . In 1630 the Bishop of Constance , as the owner of the Propstei Denkendorf, demanded the evacuation of the hospital. Apparently he wanted to revive the convent, but it did not happen. When the Spaniards destroyed Altspeyer that year, the monastery buildings were probably also destroyed and then at least partially rebuilt as a military hospital with the exception of the striking rotunda, which remained in ruins. This "Lazareth at the Wormser Thore" was finally set on fire after the end of the town fire in 1689 , as were other buildings not affected by the fire, including the Guidostift .

The monastery as a hospital building

After the residents returned to Speyer, the monastery properties were handed over to the citizens' hospital and the buildings were at least partially rebuilt and used as a hospital. After the outbreak of the French Revolution, imperial troops came from Schwetzingen to Speyer on August 2, 1792 and used all the monasteries as accommodation or as a hospital. The hospital building “am Wormserthore”, as the Holy Sepulcher Monastery was now called, was also converted. It was now a field bakery, in which the 8 field bakers and their families were also housed and had to be supplied by the only unused monastery, the nearby Klarakloster. The troop core withdrew to France just a few days later, so that only 3,000 men from Mainz and Hungary remained in Speyer. On Sunday, September 30th, 1792, around noon, French troops under General Custine came to Speyer and conquered the city a little later. To what extent the hospital building was affected is unclear, but since it was right outside the gates, it was probably captured very early. How it was used afterwards is unclear.

During their ten-day presence, the troops emptied or destroyed the Austrian provisions stores , set all ships on fire and tore down parts of the city wall and filled the trenches. After a 10-day stay, the French left Speyer and moved to their camp near Edesheim and Rußdorf. The troops advanced to Mainz on October 18 and took over the fortress . Shortly afterwards, French troops again came to Speyer and erected the first freedom tree on November 13th . On November 25th, the old administration was dissolved, the councilor Petersen was appointed mayor and another tree of freedom was erected.

For the residents of the city, the burdens caused by billeting increased, and the raw behavior of the soldiers was also a great burden. In addition, the soldiers confiscated signs and locked the shops. Nothing is known about the use of the hospital building; it may have served as a powder magazine. As Prussian and Austrian troops drew closer, the Republicans began to drive away everything they could transport and set fire to the hay and straw stacks on March 31, Easter Sunday 1793. The powder magazine at the Wormser Tor was also supposed to be set on fire, which put the St. Klara Monastery in danger, which, however, was banned by the attention of the gatekeeper who had smashed the bottom of the barrel and threw the barrels into the Nonnenbach. Around three o'clock Austrian troops with about 7,000 men entered Speyer, which was reinforced on April 2 by 5,000 soldiers from Hessen-Darmstadt with their landgrave. They were followed by other troops and prisoners over the next few days. The artillery was housed at the St. Klara monastery not far from the hospital building, which is why 50 field blacksmiths and wagons were housed in the monastery. On May 21st, order seemed to be restored, because the old city council was reinstated and the revolutionary order was abolished. The monasteries, except for the Klarakloster, which in return made bandages for the military hospitals, continued to serve as military quarters, hospital or prison for prisoners of war.

Ultimately, the peace turned out to be deceptive, as on December 28, 1793 it was heard everywhere in the city that the German troops were withdrawing after their defeat at Salmbach . As a result of this news, many citizens and also many clergy fled along the Rhine. In the evening, when the French had already conquered Speyer, the imperial reserve artillery and 2000 people with countless carts crossed the Rhine near Mannheim. On May 22nd, 1794, German troops finally crossed the Rhine and on May 25th drove the French out of Speyer, making Speyer German for a short time. But on July 14th, Speyer was conquered again by French troops, who pursued the defeated Austro-Prussian troops. Speyer was finally part of the French Republic. The hospital house fell into disrepair and was probably demolished by the French in 1811 for the construction of the Wormser Heerstraße. It can also be demolished around 1830, as a drawing by the district archive manager Peter Gayer of the ruins from 1830 has been preserved. Since the draftsman was in Speyer as early as 1816 and also drew churches that had already been demolished at the time, the drawing does not prove that the church was still standing. A later demolition is very unlikely, since the Mühlkanal has been running through the area of the former church since it was straightened in 1840/50. A petrol station was later built on the site.

architecture

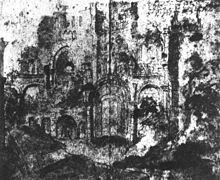

Several old drawings show that this very important Romanesque church, like the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, consisted of a so-called Templar rotunda , i.e. a rotunda typical for churches of the Templar order , to which convent buildings were attached. On a woodcut from the year 1550 from Sebastian Munster's Cosmographia , the rotunda can be seen on the far right edge, but is covered by another church. It can be seen a bit better on a copper engraving from Frans Hogenberg's Civitates Orbis Terrarum from 1537 and a similar cityscape from 1600. The building can no longer be seen on the view of the city by Matthäus Merian from 1637 , where a building located there is referred to as a hospital. The complex can be seen very well in Philipp Stürmer's picture The Free Imperial City of Speyer before its destruction in the Palatine War of Succession in 1689 . Also on the woodcut The Speyerer Bannersträger from Jacob Kallenberg's Wapen. Of the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation , the church is easy to recognize.

Floor plan of the monastery

According to a map from the Palatinate Atlas from 1967, which shows Speyer in 1525, the monastery was located directly in front of the wall of the suburb of Altspeyer, on the right side of the street leading from the Wormser Tor to the Thief Gate, one north of the Wormser Tor to secure the over the Nonnenbach leading thief thief built gate system. The monastery consisted of the conspicuous rotunda on the road near the Wormser Tor, to which a square building with an inner courtyard, probably a cloister, was attached in the northeast. On the north wall of this building was a rectangular building that extended over the entire north wall. There was also another rectangular building on the east wall of the square building, which stretched south to the cemetery. This cemetery was located south of the monastery building in front of the city wall, which, as can be seen on the map from 1730, runs from the Wormser Tor to the southwest.

literature

- Paul Warmbrunn: The former monastery of the Holy Sepulcher in Speyer . In: Barbara Schuttpelz and Paul Roland (eds.): Festschrift for Jürgen Keddigkeit for his 65th birthday (= Kaiserslauterer Jahrbuch für Pfalzische Geschichte und Volkskunde ). tape 12 . Kaiserslautern 2012, ISBN 978-3-9810838-7-3 , p. 11-30 .

- Franz Xaver Remling : Documented history of the former abbeys and monasteries in what is now Rhine Bavaria . tape 2 . Christmann, Neustadt an der Haardt 1836, p. 169–173 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- Christoph Lehmann, Johann Melchior Fuchs: Chronica of the Freyen Reichs city Speier . Oehrling, 1698, p. 503–504 ( full text in Google Book Search).

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Franz Joseph Mone: History and description of Speyer . Oswald, 1817, p. 91 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- ^ A b c d Franz Xaver Remling: Documented history of the former abbeys and monasteries in what is now Rhine Bavaria . tape 2 . Christmann, Neustadt an der Haardt 1836 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Franz Xaver Remling : Documented history of the former abbeys and monasteries in what is now Rhine Bavaria , Volume 2, p. 171, Neustadt, 1836; (Digital scan)

- ↑ Regest of the deed of gift

- ^ Regest of the sales deed

- ^ Website on Eibensbach and the Kaplanei Foundation

- ↑ Website about the paintings in the Marienkirche Eibensbach

- ^ Franz Xaver Remling: Documentary history of the former abbeys and monasteries in what is now Rhine Bavaria , Volume 2, p. 171, footnote 9, Neustadt, 1836; (Digital scan)

- ^ Franz Xaver Remling: Documented history of the former abbeys and monasteries in what is now Rhine Bavaria , Volume 2, p. 171, Neustadt, 1836; (Digital scan)

- ^ Franz Xaver Remling: Documentary history of the former abbeys and monasteries in what is now Rhine Bavaria , Volume 2, p. 173, Neustadt, 1836; (Digital scan)

- ↑ a b Robert Plötz, Peter Rückert (Ed.): Jakobuskult im Rheinland . Gunter Narr Verlag, Neustadt an der Haardt 2004, ISBN 978-3-8233-6038-4 , p. 108–109 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

Coordinates: 49 ° 19 ′ 38.9 " N , 8 ° 25 ′ 47.1" E