History of the city of Speyer

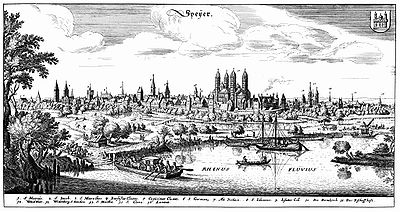

The history of the city of Speyer begins in 10 BC. With the establishment of a Roman camp . The name Spira , from which the current name Speyer finally developed, appears for the first time in 614. Speyer gained fame primarily through the Reichstag and the Imperial Cathedral .

Timetable

- 10 BC BC: The first Roman military camp Noviomagus , settlement of the Germanic Nemeters on the left bank of the Rhine, civil settlement in front of the military camp

- around 83: Noviomagus civil settlement becomes capital in the territory of the Nemeter (Civitas Nemetum)

- 346: Jesse is mentioned as a bishop for Speyer .

- 496/506: Franconian settlement, first mention of the name Spira

- around 800: Beginning of the Carolingian cathedral construction

- 838: first of a total of 50 court and imperial days in Speyer

- 946: Market and coin law

- 969: Emperor Otto the Great's immunity privilege ; Bishop becomes city lord, construction of the city wall begins

- 1030: Emperor Konrad II lays the foundation stone for the Speyer Cathedral .

- 1047: Emperor Heinrich III. transfers the body of Saint Guido from Pomposa to Speyer.

- 1076: King Heinrich IV sets out from Speyer to do penance to Canossa .

- 1084: The first Jewish community settles in Speyer

- 1111: The great freedom letter of Heinrich V.

- 1193: Emperor Heinrich VI. concludes a contract with his prisoner Richard the Lionheart at the Reichstag in Speyer (March 21, 193 - March 25, 193) about the ransom of 100,000 silver marks to be paid.

- 1226: Speyer becomes a member of the Rhenish Association of Cities

- 1230: first Speyer town charter

- 1294: The bishop loses most of his previous rights and the city of Speyer is from now on a free imperial city .

- 1526: The Reichstag in Speyer negotiates Luther's teachings.

- 1527: Speyer becomes the seat of the Imperial Chamber Court (until 1689)

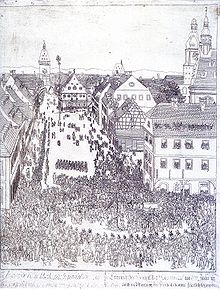

- 1529: At the Reichstag in Speyer on April 19, the evangelical imperial estates "protest" against the resolutions hostile to the Reformation ( Speyer Protestation )

- 1544: Great Jewish privilege granted by Emperor Karl V.

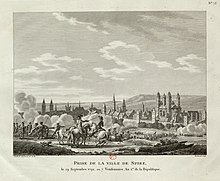

- 1689: The city is almost completely destroyed by French troops under General Mélac during the War of the Palatinate Succession

- 1792: Speyer is conquered by French revolutionary troops and remains under French rule until 1814. It becomes the seat of a sub-prefecture in the Donnersberg department .

- 1816: The city becomes the district capital of the Palatinate and is the seat of the government of the Bavarian Rhine District, later the Bavarian Palatinate

- 1918: French occupation (until 1930)

- 1923/24: establishment of the autonomous government of the Palatinate by separatists; Assassination attempt on its president Franz Josef Heinz

- 1936: occupation of the Rhineland; Speyer becomes a garrison town again

- 1938: opening of the first permanent bridge over the Rhine ; Pogrom Night : National Socialists set the synagogue on fire

- 1945: Rhine bridge blown up by German troops. American troops occupy the city, which are soon relieved by the French army

- 1947: Foundation of the German University for Administrative Sciences

- 1956: New Rhine Bridge; first town twinning with Spalding (Great Britain), 1959 with Chartres (France)

- 1969: The Speyer district is merged with the Ludwigshafen district

- 1990: The city celebrates its 2000th anniversary.

- 2011: The city celebrates 900 years of civil liberty.

Celts, Romans and Teutons

The time before the Romans

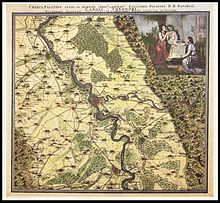

Of great importance for the development of Speyer was its convenient location on the Rhine , a central central European traffic artery. The immediate proximity to the river on the flood-proof high bank was an advantage, as was the nearby confluence of the Neckar valley into the Rhine plain, which established the connection to the southeast towards the Danube, and the proximity of the Kaiserslautern Basin, which conveyed traffic to the west and southwest . The existence of five Rhine ferries in the immediate vicinity of the city in the Middle Ages also indicates the importance of Speyer as a traffic junction .

Numerous finds from the Neolithic , Bronze Age , Hallstatt and Latène Age suggest that the Rhine bank terraces in Speyer, in particular the lower terrace tongue in the immediate vicinity of the river, have always been interesting places to settle. At least five settlements from the Bronze Age can be identified: in Speyer-Nord , on Roßsprung, in the area of the town hall, on Rosensteiner Hang and in the Vogelgesang residential area.

One of the most famous finds from this time (around 1,500 BC) is the " Golden Hat ", which was found 10 km northwest of Speyer, near Schifferstadt , and is now kept in the Palatinate History Museum in Speyer. In the second century BC, the area of Speyer was the settlement area of the Celtic Mediomatrics, who built a small fortified settlement (oppidum) south of the Speyerbach estuary .

Around 70 BC BC Suebi crossed the Upper Rhine under Ariovistus in association with other Germanic tribes, including the Nemeters , and invaded Gaul. Speyer may have been captured by the Nemeters. With the help of the Romans, Ariovistus became 58 BC. BC ( Gallic War ) repulsed across the Rhine. The Nemeters are first mentioned in Caesars De Bello Gallico . However, it is not clear whether Nemeters stayed in the Speyer area at this time or were only settled there a few years later (approx. 10 BC). The Roman name of Speyer from this time on was initially Noviomagus Nemetum, then Civitas Nemetum. Archaeological Germanic finds in Speyer exist from the last decade of the 1st century BC. A Celtic grave in Johannesstrasse from the period between 50 and 20 BC is therefore an interesting find. As Celtic graves are the exception in the Palatinate and Upper Rhine during this period.

The Romans on the Rhine

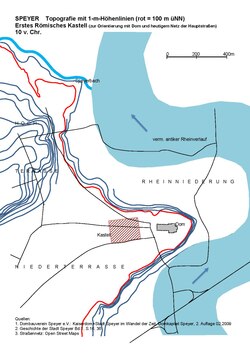

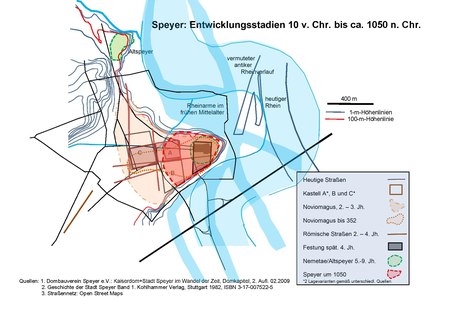

After the subjugation of Gaul by the Romans in 50 BC. BC, the Rhine became part of the border of the Roman Empire , even if the area was still outside the military scene . 15 BC The Romans conquered the area of the Celtic Raetians and Vindeliker between the Alps and the Danube, but attempts to subdue areas on the right bank of the Rhine failed for the time being. At the instigation of Emperor Tiberius, Drusus had castles built for legions and auxiliary troops from the Alps to the North Sea along the Rhine . One of these camps and forts was Speyer, which was located on the Roman Rheintalstrasse around 10 BC. It was probably built for a 500-strong infantry force. The Romans also used the favorable location of the Hochgestade in the immediate vicinity of the Rhine. This first fort was located in the eastern area of today's Maximilianstrasse, roughly between Kleiner Pfaffengasse and Großer Himmelsgasse. The southern fortification ditch could be dug along the Kleine Pfaffengasse.

This Roman military post became the impetus for city building. Partly at the instigation or with the permission of the Romans, the Germanic Nemeters had settled under Emperor Augustus in the area of the Vorderpfalz ; Germanic tribes had also settled in the neighboring regions of what is now Rheinhessen and Alsace: the Vangionen and the Triboker . The finds in Speyer indicate that not only Romans were stationed there. Sometimes it was either Germanic soldiers from a regular auxiliary unit or a tumultuous contingent under their own leadership. The existence of the first fort was short-lived. Finds indicate that two more forts, each slightly offset from the first, were built in the period that followed. The second was built up to about 10 AD immediately south of the first, whereby the north wall in the Kleine Pfaffengasse roughly coincided with the south wall of the first fort. Remains of the second fort were found during excavations in the area of the Judenhof. The south of the fort presumably bordered the upper edge of the high bank, where the Rhine flowed directly past at that time. There was a system of moats to the west and north. The new construction of the second fort corresponds to the reorganization of the Rhine line after the Roman defeat in the Varus Battle .

In the area of this second camp, an extensive civilian settlement ( vicus ) arose , one of the germ cells of ancient Speyer. On both sides of the western arterial road, with the approval of the Romans, traders, craftsmen, soldiers' families and the entertainment industry settled down. About 3000 m² of this settlement were examined during the construction work for the foundation hospital. The settlement presumably extended from Herdstrasse to Zeppelinstrasse. It experienced its first heyday in the 2nd century. The settlement area was around 25 hectares. Another smaller settlement area from this period can be found at the opposite eastern end of the fort in the area of the cathedral hill.

From 30 AD, representative buildings in a U-shaped arrangement were built in the settlement on the south side of the street in the area of the foundation hospital, presumably a market forum, which underlines the growing importance of the early Roman Speyer. From this it is in turn concluded that a market right (ius nundinarum) already existed for the vicus . The salary of the troops was an essential basis for economic development. Intensive trade connections served a large part of their supply of everyday goods and reached as far as central Italy, the Rhone, southern Gaul and Spain. Speyer was also a stage stop on the important Rheinuferstraße.

Around the same time, the second fort was replaced by a third one - a little inland, between the middle Maximilianstrasse and Ludwigstrasse. The reason for this could have been flood problems, but also a lack of space or simply the need for renewal. According to the findings so far, this last fort seems to have been considerably larger than its predecessor. According to the finds, this fort existed at least until the withdrawal of the auxiliary troops in 74 after the conquest of the areas on the right bank of the Rhine.

After the conquest of the areas on the right bank of the Rhine, Speyer was no longer of military importance as a border town. From 83 Speyer belonged to the province of Germania superior . After the military withdrew, the fort was abandoned, the civilian settlement was given the right to self-government and, due to its supra-regional importance in the Nemeter area, became the seat of the Civitas Nemetum regional authority . Civitates were self-governing corporations under " peregrine " law, the structure of which was based heavily on the structure of Roman cities. The Civitas administrative offices on the Rhine had the legal status of vicus ; but there are milestones where Speyer is also referred to as “ colonia ”. The Civitas Nemetum comprised the area of what is now the Vorderpfalz and Northern Alsace. How far areas of the Palatinate Forest belonged is not known. Vicus and civitas formed a unit, and all residents were considered “cives” or “incolae” of the civitas. As the seat of a regional administrative center, a small-town representative city emerged. Due to the triangular shape of the terrace tongue, the settlement could only expand to the west and, with an area of no more than 25 hectares, approximated the later Salian city limits with the city wall. In the old town of Speyer today, practically no building work below street level is possible without encountering remnants of that time. The numerous finds - among them z. B. the oldest preserved and still closed wine bottle in Germany, the so-called Roman wine from Speyer - can also be viewed in the Palatinate History Museum.

Around 150 the city appeared under the Celtic name Noviomagus (Neufeld) in the world map of the Greek Ptolemy ; the same name is in the Itinerarium Antonini , a travel guide of Antonius from the time of Caracalla (211-217) and on the Tabula Peutingeriana , a road map from the 3rd century. It can also be found on distance columns along Rheinuferstraße. Two new traffic axes can be identified from this time. A six to eight meter wide, 700 m long east-west axis from the period between 80 and 100 AD, laid out as a boulevard like a Decumanus , began at the cathedral hill and led over Kleine Pfaffengasse to Königsplatz and in a straight line further west. It was lined with rows of colonnades along its entire length .

Another east-west street, the old Vicus Street, continued to exist and is occupied immediately north of the foundation hospital.

Furthermore, a north-south axis was created, for example from Hagedorngasse in the north, over the Kaufhof area, to the old Vicus-Strasse in the south. The fort has largely been over-planned. The area of the former third fort was obviously used to erect representative buildings that correspond to the importance of the city. Massive remains of the wall and other finds of special quality that were discovered in the area of Königsplatz indicate that a forum area with a temple stood there. The dimensions of the Jupiter column found in the courtyard indicate a size that is comparable to the famous Jupiter column from Mainz. Due to numerous other finds of pillars and altars, it can be assumed that the Jupiter cult was given a special rank in Speyer. The centrally located district in the Königsplatz area was the administrative and business center. The discovery of a parapet stone with a corresponding inscription proves that there was also an amphitheater , as was common in cities of this size and importance.

In 2013, Roman graves were discovered during excavations on the Marienheim site, which belong to a burial ground from the 1st to 5th centuries in the area of today's western Ludwigstrasse (suburban area). The 120 grave sites included 4 stone sarcophagi, 48 body burials and about 70 cremation graves with rich grave goods.

Speyer at the time of the Great Migration

The storms of the Migration Period did not spare Roman Speyer either. Initially, the flourishing development of Speyer continued after the Danube border collapsed between 166 and 170 and despite the increasing Germanic invasions across the Limes . For a time the Romans were able to repel the Alamanni , who appeared from 213 onwards. From 260 onwards the constant attacks of the Alamanni on the Limes could no longer be repulsed, the Roman imperial border had to be withdrawn to the Rhine, and Speyer became a border town again ( Limesfall ). People fleeing across the Rhine had to be taken into Speyer. Initially, this did not lead to any serious changes for Noviomagus. However, the Alemanni managed to cross the Rhine again and again, mostly in winter when it was frozen over, and around 275 the city was almost completely destroyed. Numerous skeleton finds and traces of fire testify to the extent of the destruction. Nothing is known about the fate of the population. From 286, under Emperor Diocletian , the northern provinces and the administration were reorganized; the civil and military administrations were separated. Infrastructure and localities were rebuilt. Noviomagus flourished again, whereby the settlement development was concentrated only between Domhügel and Heydenreichstraße while maintaining the Roman main street.

Another destruction by invading Alemanni under their prince Chnodomar took place around 352, who conquered the entire left bank of the Rhine. As part of the reconquest campaigns under Constantinus II and Julian from 355 onwards, Civitas Nemetum was wrested from the Alemanni again. The Alemanni incursions continued, however, the situation remained unsafe and the settlement was not rebuilt. Rather, Emperor Valentinian I began to fortify the left bank of the Rhine. Small units with their own names were stationed for border defense. Speyer became a garrison location again in 369 at the latest. For Nemetae , as Speyer was now called, the "Vindices" are listed in a troop manual (Notitia dignitatum). A mighty fortress with 2.5 m thick defensive walls was built in the area of the cathedral hill. The northern wall ran parallel to the north side of the later cathedral. The course of the southern wall at the foot of the slope of the terrace tongue is probably related to the construction of a Rhine port, which took place at the same time. The edge corresponds to the south side of the museum, in front of which the remains of ships were found underground during its expansion. This resulted in a north-south extension of around 230 m for the fortress. The east-west extension could not yet be determined exactly, but it should have been about the length of the cathedral. This area offered enough space for the civilian population in times of need. Findings in the fortress area suggest that there was an early Christian community. For the year 346, Jesse is named as the first Speyer bishop, so that Speyer is occupied as a bishopric from this point in time . The grave finds just outside the fortress indicate that the rural population was still pagan. Even if the settlement was not rebuilt, there was enough confidence in security that many settlers returned to the area. Obviously some of the Alemanni remained with the approval of the Romans.

In 406, Suebi , Vandals and Sarmatian Alans put pressure from advancing Huns across the Rhine and overran Speyer on their way into inner Gaul (see Rhine crossing from 406 ). A richly decorated princely grave in Altlußheim on the right bank of the Rhine , about 4 km from Speyer, testifies to the presence of Alano- Sarmatians , Huns and East Germans .

This did not mean the end of Roman life in the region, but with it the Romanesque population began to withdraw from the area on the left bank of the Rhine (Vorderpfalz and Northern Alsace). This process was presumably faster in the country than in the cities and it can be assumed that Speyer lost much of its importance. The Romans tried to hold the Rhine border by assigning the defense of Germanic peoples as federates . The Franks were supposed to take over this task for the province of Upper Germany (Germania prima) , but they did not prevent such incursions as 406. Even the brief settlement of the Burgundians in 413 in the Worms area did not bring the desired security and the Roman order remained fragile.

While most of the Germanic peoples who came across the Rhine moved further west, from 450 onwards a gradual land seizure in the form of court formations can be observed, also in the area around Speyer. At least three such branches can be detected on Woogbach and Roßsprung, one to two km northwest of the fortress (cathedral hill). From 454 the Romans gave up their attempts to hold the Rhine border; the Speyer troops were incorporated into the Roman field army. The influx of Germanic peoples increased. The Upper Rhine area became Alemannic. Due to their influence, the decline of the Romanesque way of life in the Speyer - Strasbourg area took place more quickly than between Worms and Cologne. Speyer no longer fully participated in the last Roman prosperity on the Rhine in the 5th century.

Around 475, the Winternheim settlement was built 2 km south-west of the fortress and 500 m south-west of what later became the German pen, directly on the upper edge of the lower terrace (today's Vogelgesang residential area). It initially consisted of a single courtyard and was later extended to the west. Since it is assumed that the entire left Upper Rhine region was in Alemannic hands at the time, it was surprising to find that the North Sea Germans, i.e. Saxons, can be assigned to them. Based on similar finds further north, it can be assumed that other tribes besides Alemanni also settled in the area. Winternheim, probably a weaving village, existed until the 12th century and had a parish church in St. Ulrich. After his abandonment, the village became a desert , which finally disappeared from the surface in the 15th century, while the last traces of the church disappeared after the 16th century. Remnants of the village came to light in 1978 when building land was opened up and were excavated on an area of 30,000 m 2 by 1981 . In 1983 the parish church with a cemetery was excavated west of the Closweg.

In the 5th century the village of Altspeyer , also called Villa Spira , developed on the area between Bahnhofstrasse, Hirschgraben / Petschengasse and the Nonnenbach , which later became the suburb of Altspeyer. Due to the settlement and construction activity in the 18th – 20th Apart from numerous graves, little is known about it.

The fortress on the cathedral hill still existed around 500, but it cannot be determined what proportion the Romanesque population still had. The transition of the name Nemetae to Spira indicates that Latin was soon no longer spoken.

Emperors, bishops and citizens - the way to the city

A newbeginning

In a battle in 496/497 near Zülpich and another battle in 506, the Franks under Clovis defeated the Alamanni and Speyer became part of the Frankish kingdom. With that Speyer got again connection to the Gallic-Roman culture. As part of the reorganization of the administration, Romanised officials and bishops from southern Gaul came to the Rhine. The Franconians also largely followed their predecessors in terms of the administrative structure, for example in setting up the districts. The new Speyergau corresponded roughly to the civitas Nemetum.

In addition to an orderly administration, the expansion of the Frankish Empire to the east also brought Speyer out of isolation economically, and old and new trade relations were resumed. Christianity, oppressed under the Alamanni, could flourish again. The settlement activity increased again under Frankish rule. At least some of the branches that emerged near Speyer around 500 (Altspeyer, Winternheim, Marrenheim, Heiligenstein , Mechtersheim , Otterstadt and Waldsee) were probably of Franconian origin. Similar settlements can also be found in the immediate vicinity of Mainz and Trier.

For the first time, instead of Noviomagus, the name Spira, introduced by the Alemanni, is mentioned in the “Notitia Galliarum” from the 6th century. Thus the city took over the name of the suburb Altspeyer, which can already be deduced in 496/509. In this context, another bishop, Hilderich von Speyer , is named in the files of the Paris Council of 614, who took part in the National Council of the Franconian Empire reunited by Chlothar II . The re-establishment of the diocese of Speyer is assumed for the middle of the 5th century. The Rhenish dioceses were characterized by the fact that, in contrast to the Gau division, they extended on both sides of the Rhine. The first churches and monasteries in Speyer emerged in the 6th and 7th centuries. The establishment of the diocese of Speyer must also have been linked to the construction of a cathedral for the bishop, which is also supported by the appearance of the patrons, Maria and Stephan since 662/664. The earliest detectable site is St. German south of the city. With a length of 19.7 m, a ship's breadth of 8.9 m and a transept of 15.5 m, St. German was generously dimensioned for its time, although its function is not exactly clear. Another early church was St. Stephan in the area of today's state archives, also outside the former city wall. For a time this was considered to be the predecessor of the cathedral and served as the burial place of the bishops. There is also evidence of a church of St. Maximus, but its location is not known.

With the emergence of the bishopric and the construction of a fortified bishop's palace , Speyer began to develop as a center of spiritual and secular power. The Frankish King Sigibert III. assured the Speyer Church under Bishop Principius around 650 tithes of all proceeds from the royal estates in Speyergau; in addition, she was exempt from taxation by the count. Principius successor Dagobert I was 664/66 of the still underage King Childeric II. The immunity granted. A number of sources of income were associated with this, such as the Heerbann and the " Stopha ". These privileges were confirmed to Bishop Freido on June 25, 782 by Charlemagne during the Saxon Wars .

In the period that followed, the transfer of privileges was a means of kings and emperors to create loyal pillars across the country for the regional nobility. With the increasing power of the bishops, the emerging bourgeoisie in Speyer soon found itself in a tense relationship between the nobility of Speyergau, the church and the emperor. The resulting disputes were to shape the emancipation history of the city for almost six centuries.

The Carolingians built a royal palace in Speyer and Charlemagne stayed several times in the city. Ludwig the Pious held court in Speyer in 838. This marked the beginning of a series of 50 Imperial Diets held in Speyer by 1570 .

Bishops as city lords

The town's lord was a Gaugraf on behalf of the king, but rights were transferred to the bishop as early as the sixth and seventh centuries, for example by the Frankish king Childerich II , which led to a gradual shift in power. Under the Carolingians , Speyer was not of great political importance. The kings only spent a short time in the city; B. Charlemagne at the end of August 774, Lothar I in the summer of 841 or Ludwig the German in February 842. The prosperity and power of the Speyer Church, on the other hand, increased further in the 8th and 9th centuries. She owned numerous goods in the entire Speyergau as well as in the vicinity of the city. Within a radius of 8 km around the city, the bishop even had a closed belt of possessions.

In the literature there are references to several cathedral structures . Accordingly, the Frankish king Dagobert I had a first cathedral built for the bishops of Speyer around 636. St. Stephan was rebuilt either inside or as a whole at the end of the 8th century. 782 speaks of a cathedral church with the traditional name Church of St. Mary or St. Stephen . In 846, Bishop Gebehard (846–880) consecrated a second cathedral. In 858 there is talk of a cathedral, the Cathedral of the Holy Virgin Mary, which stands in the city of Speyer , the Church of St. Mary built in the city of Speyer, or the aforementioned Holy Cathedral . In 865 the name was built in honor of St. Mary, and consecrated in 891 in honor of St. Mary . In further writings 853/54 the Speyer Cathedral is mentioned . Therefore, the construction of a Carolingian cathedral in Speyer is assumed for this period. The location includes a. Sections in the former and now poorly accessible Roman street grid as well as under the western half of today's cathedral are in question. No remains have been found so far.

With the division of the empire ( Treaty of Verdun 843) after the death of Ludwig the Pious , Speyer was now in the East Franconian part, which one of the three sons, Ludwig the German , took over. In the following years Speyer bishops took part in numerous synods and conducted negotiations in Paris and Rome on behalf of the emperor. In 891 Bishop Gebhard I received a gift from King Arnulf for the cathedral monastery. In 911 the East Franconian line of the Carolingians ended for lack of heir to the throne and the Franconian Duke Konrad I was elected king.

During his reign in 913, a violent dispute between Bishop Einhard I and Gaugraf Werner is documented for the first time . The bishop was part of Konrad I, who, with the support of the bishops, was in dispute with oppositional dukes. Gaugraf Werner, ancestor of the Salier family , who gladly expanded his possessions at the expense of the church, blinded the bishop, presumably because of the division of sovereign rights in Speyer. The bishop did not recover from it and died in 918. Conrad I was followed in 919 by the Saxons Heinrich I and 936 Otto the Great .

On March 13, 949, Salierduke Konrad and Count des Speyergaus ( Konrad the Red ), son of Count Werner and son-in-law of Emperor Otto, transferred important rights and goods to the Speyer Bishop Reginbald , which were associated with significant income. These included the right to coins , half a duty, market supervision and market taxes, the salt pfennig and the compulsory pfennig and a tax on wine that was only levied on foreigners. This decisively strengthened the position of the Speyer bishop, because three years earlier he had half the right to mint, half the right to customs, jurisdiction over thieves, trade sovereignty in the city and the like. get various taxes transferred. The son's atonement for his father's crime against Bishop Einhard is seen as the background to this important transmission. Thus the city of Speyer and its suburbs were exempt from counts or other public courts, apart from that of the episcopal bailiff. An important milestone in the direction of becoming a town in the award document of 949 was that its content was made known to the clergy and the townspeople. With this handover the actual rule of the city of the bishops began. With this strong economic base of the bishops, to which the Rhine ferries belonged, there was hardly anything left in favor of separating the episcopal city from the market and merchant settlement.

The increase in power of the Speyer bishops did not end there. Otto the Great also relied on the support of the bishops (Ottonian imperial church policy). During his Italian campaign, in which the Speyer Bishop Otger also took part, in October 969 he granted the Episcopal Church the privilege of immunity , its own jurisdiction and control over coins and customs . With this, the counts left the city as a power factor and Speyer finally fell under the protection, control and rule of the bishops. With the right to mint, Speyer developed into one of the most important mints in the empire by the 12th century.

Bishop Balderich (970–986), one of the most learned men of his time, founded the cathedral school in Speyer, based on the St. Gallen model , which was to become one of the most important in the empire. Under the Salian and Staufer emperors, the Speyer bishops and students of the cathedral school increasingly assumed the role of governors and functionaries of the empire. Speyer seemed to take on the character of a royal city or imperial country city .

The first walling of the still small urban area is occupied for 969 and was done at the instigation of the bishop. This beginning of the Speyer city fortifications was supposed to protect the city above all from the Hungarian invasions that took place around this time. The urban area ranged from the Episcopal Church to today's Dreifaltigkeitskirche and Webergasse. The walled area was still relatively small and is estimated to be between 8 and 14 hectares. The bishop was not only responsible for the walled city (civitas), but also the immediate neighborhood (“circuitus” or “marcha”) with the suburb directly adjacent (market and merchant settlement) and the village of Altspeyer. Thus Speyer was not yet a closed urban settlement.

The 10th century, after a period of stagnation, was accompanied by an increase in population and economic activity. The city's convenient location (Rhine, Rhine crossings, highways) favored economic development. This went hand in hand with significant steps towards becoming a city. Merchants settled in the suburbs (documented for the first time in 946) and a port with an adjoining market area (wood market, fish market) developed in the area of the Speyerbach estuary. The Ottonian road system is completely disappearing. The urban structure of today's Speyer and the actual city development, the process of which took over 200 years, goes back to this time. During this time the most glamorous section of the Speyer town history began, which would last until the 15th century. The history of the city was also the history of the empire. Even if two well-known quotes about Speyer from the 10th and 11th centuries are not to be taken literally, they still reflect the development of the city. A pupil of the cathedral school (973–981) and later Speyer bishop (1004–1031), the poet Walter von Speyer , described Speyer as “vaccina” (Kühstadt) in a dedication for his teacher and predecessor, Bishop Balderich (970–986) . Ottonian Speyer was still very much rural. In 980 the bishop in Speyer recruited twenty armed horsemen for Emperor Otto's Italian campaign. For example, Worms provided forty, Mainz and Strasbourg a hundred each.

About 150 years later, on the occasion of the burial of Emperor Heinrich V in Speyer Cathedral in 1125, the English monk Ordericus Vitalis wrote about Speyer from the metropolis Germaniae (capital of Germany). This expresses the political importance of the city at that time, but the concept of “metropolis” at that time cannot be compared with today's term “capital”.

The Salier, cathedral building and city extensions

On September 4, 1024 , Salier Konrad II , who came from Speyergau , was elected king of Germany near Oppenheim am Rhein. The Salians are considered to be the second founders of Speyer; with them the city moved into the center of imperial politics and became the spiritual center of the Salian kingdom. With the election of Konrad II began the targeted promotion of the city and church, which was continued by the Hohenstaufen. When Konrad II and his wife Gisela were not on the road, they mostly lived in Limburg an der Haardt and were often in Speyer. The town clerk Christoph Lehmann (1568–1638) wrote in the "Chronica der Freyen Reichs Statt Speyer": "Because Conrad lived a lot and often in Speyer in the royal palatio, they called Cunradum the Speyer."

In the meantime, crowned emperor in 1027, he laid the foundation stone for the Speyer Cathedral in Speyer, on the site of the former bishop's church , on the tip of the lower terrace closest to the Rhine. The construction work began in 1030, according to other research results in 1027. Speyer, together with Goslar, became the most important place of Salian founding activity .

The cathedral was to serve as a burial place for his dynasty and "the expression of imperial power and dignity sculpted in stone". and was the largest church in Christendom at the time. Konrad had experienced builders brought to the city and a. the Speyer Bishop Reginald from St. Gallen, Bishop Benno von Osnabrück and Bishop Otto von Bamberg . The cathedral construction, which lasted for several decades, gave the decisive impetus for the further development of the city; the arrival of numerous craftsmen, artists and traders brought an economic boom.

Other important buildings and extensions were built together with the cathedral. Immediately at the northeast corner, the royal and bishop's palace was added, which was probably completed in 1044/45. Since the Carolingian era it was customary for the bishops to expand their residence in such a way that it could also serve the residence of the kings. The Palatinate was a 74 m long, 16 m wide, three-story building with a floor height of 6 m, had its own chapel and a connecting passage to the cathedral. The dimensions and elaborate architectural structure were unparalleled for secular buildings in the Salier period. With the city wall running to the north, the cathedral and the Palatinate formed the Freithof . On the south side of the cathedral a square cloister , the two-story cathedral monastery building and the cloister building of the cathedral chapter were built . Overall, the cathedral, the Palatinate and the other additions made up a representative building complex that was unparalleled in the empire.

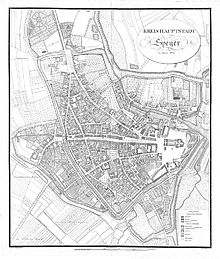

The extensive and long-term construction activity led to the expansion of the city. Overall, it was given a largely new orientation, and the characteristic floor plan was created with the three streets spreading fan-like from the cathedral to the west. After the course of the stream was covered, the middle one was gradually extended to 650 m and a width of up to 50 m, to the Via Triumphalis between the cathedral and the old gate that was later built . Even if the parallel Korngasse later rejuvenated a section, this east-west axis, today's Maximilianstrasse , still shapes the cityscape today. The unusual width of the street can still be seen on the old gate and between the cathedral and the old coin. During this time the city was expanded to approx. 50 hectares with a new walling, which was completed around 1080. The suburb of Altspeyer and the attached Jewish quarter also had its own wall at this time.

The monastery of St. Johannes Evangelist / St. Guido on the Weidenberg, presumably old Salian property, was started under Emperor Konrad II . In the Salian period, the St. Germansstift on the Germansberg and, under Bishop Sigibodo , the Trinity / All Saints Monastery not far from the cathedral.

Konrad II died on June 4, 1039 and was buried in the cathedral, which was still under construction, which under his son, the young Heinrich III. was continued. He, too, was very fond of the city, often visited "his beloved Speyer" and endowed the cathedral 1043-1046 with the magnificent Golden Gospels of Henry III ( Codex Aureus Escorialiensis , today in Madrid), one probably in the monastery Echternach incurred Gospels . In this it says u. a .: " Spira fit insignis Heinrici munere regis (Speyer is awarded and enhanced by the promotional work of King Heinrich)". In 1046 Heinrich III. from his coronation as emperor in Italy relics to Speyer, a. a. the bones of the blessed Guido von Pomposa , which were solemnly buried in 1047 in the still young St. Johannes Stift on the Weidenberg (later St. Guido Stift). After Goslar and Regensburg Speyer was under Heinrich III. and under Henry V the most preferred palatinate in the empire. Henry III. was buried after his death on October 28, 1056 in the presence of Pope Viktor II in the still unfinished cathedral.

His widow, Agnes von Poitou , who continued the reign for her six-year-old son, Henry IV , was favored by the city and the early Salian cathedral, as was Henry IV himself later, who confirmed the privilege of immunity.

The political relations between the Speyer bishops and the empire were further intensified. In the dispute between the emperors and the popes ( investiture dispute ), they were among the most loyal partisans of Henry IV and Henry V, z. B. Heinrich I von Scharfenberg (1067-1072), Rüdiger Huzmann (1073-1090), Johannes I, Count in Kraichgau (1090-1104) and Bruno von Saarbrücken (1107-1123). It was Bishop Rüdiger who brought the letter of deposition to Pope Gregor VII in 1076 and Bishop Bruno, as Chancellor of Henry V, negotiated the Worms Concordat with Pope Calixt II .

Heinrich IV set out from Speyer for Canossa in December 1076 , accompanied by Bishop Hutzmann. Because of his partisanship for the emperor, the bishop was banned by the pope until the end of his life in 1090 .

At the cathedral, static problems soon had to be overcome and the foundation secured against flooding from the nearby Rhine. In 1080, at the instigation of Henry IV, work began on the late Salian cathedral building (Speyer II), which gave the city a second growth spurt. Up until the completion in 1102, architectural history was written in Speyer: The central nave, which was raised to its present height, was vaulted for the first time at a height of 33 m. The cathedral was the largest church building of its time and, with its monumentality, symbolized imperial power and Christianity. After Conrad II was buried in it, the cathedral became the church of the Holy Sepulcher for seven other emperors and kings. After the destruction of Cluny Abbey , the cathedral is still the largest Romanesque building today .

At the beginning of the following century, a further expansion of the Speyer city wall became necessary and in the period between 1200 and 1230 the stacking area (fish market) was included in the walling. An indication of the increasing population can also be seen in the establishment of new parish churches; in the second half of the 12th century St. Bartholomäus, St. Jakob and St. Peter were created. The increasing residential density within the walls and the associated urbanity represented a departure from the rural location and a further important step in urban development. This may also be expressed in the fact that from the end of the 11th century "Spira" was the sole name of the City is used. Until then, the city was either called "civitas Spira vel Nemeta" or even just "Nemetum" in documents.

Konrad II and his successors equipped the cathedral monastery with goods and bailiwick rights that formed the basis for a successful economy. This included the area of Bruchsal and the associated Lusshardt forest , widely scattered property on the upper Neckar, in the northern Black Forest, in today's Palatinate and in Kraichgau . In a further distance, the bishopric got goods in the Hunsrück , the nearby England and the Hessian mountains. Heinrich IV gave the church of Speyer little by little possessions in the Wetterau , in the Remstal , in the Nahegau , in Saxony and gave it the counties of Lutramsforst (southern Palatinate) and Forchheim . In fact, the entire Speyergau came into the possession of the church.

In a document in connection with the settlement of Jews in 1084, the population of Speyer was the first to speak of “cives” as citizens, and in the following years an independent municipal law developed. This right is mentioned in another document from Henry IV from 1101 as “ius civile” or “ius civium”. In 1084, a Rhine port in the area of the Speyerbach estuary is also mentioned for the first time. At that time, Speyer was the third largest storage area and the largest wine transhipment point on the Upper Rhine. Cloth, fabrics, wine, spices, grain, fruit, millstones, ceramics and weapons were traded. The slave market also flourished from ancient times to the 11th century.

Bishop Hutzmann's successor in 1090 was Heinrich IV's nephew and confidante, Johannes Graf im Kraichgau. In his time until 1114, the diocese received further goods from the emperor in the Rastatt area . Heinrich IV died in Liège in 1106 and was buried by his son, Heinrich V, on August 14, 1111 in the royal choir of the Speyer Cathedral. Until then, Henry IV had been in the unconsecrated Afra chapel.

The Jewish community of Speyer

In 1084, at the instigation of Bishop Rüdiger Huzmann , one of the first Jewish communities in the Holy Roman Empire settled in Speyer. Speyer, together with Worms and Mainz, belonged to the so-called ShUM cities and soon developed into one of the most important centers of Ashkenazi Jewry .

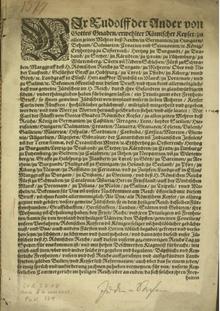

The great letter of freedom of 1111

On the day of his father's burial in Speyer Cathedral, August 14, 1111, Heinrich V granted the city further privileges. The Great Letter of Freedom was the first city in Germany to grant its citizens personal freedoms, and the granting of these citizens' privileges marked the beginning of the development of the Free Imperial City.

The solemn introduction read: According to the fact that we have resolved to exalt ourselves before other cities by divine grace and assistance of the city in the memory of our ancestors and because of the steadfast loyalty of their citizens to us, we have decided to use their rights from imperial power on the advice of ours Fasten princes . Together with his picture, the letter was affixed in gold letters above the cathedral portal, where it was lost in the course of the later damage to the cathedral.

The privilege freed the people of Speyer from the oppressive inheritance tax and granted them a say in the case of coin deterioration. In addition, the accommodation and transport obligation (on the Rhine) was lifted and the citizens were no longer forced to buy the ban wine. They could no longer be tried in extra-urban courts and were exempt from market and trade taxes, as well as city duties. These privileges, which were also due to immigrants, created the prerequisites for a personally free population with a uniform legal status, e.g. B. Ownership Guarantee. This letter became a model for other cities in the empire. What became clear for the first time with these privileges was the developing interest of the empire in strengthening the bourgeoisie as a counterweight to episcopal power.

In 1116, Bishop Bruno of Saarbrücken sided with the nobles who opposed Heinrich V in connection with the investiture controversy under the leadership of his brother, Archbishop Adalbert of Mainz . Speyer, loyal to the Salians and Staufers in its partisanship, then drove the bishop out of the city. It was the first time that a documented political act by the citizens of Speyer was manifested.

Heinrich V, who succeeded in negotiating a compromise in the investiture dispute with Pope Calixtus II , died childless in Utrecht in 1125 and was buried as the last Salic emperor in the Speyer Cathedral.

Staufer

In the subsequent dispute over the royal crown, the Welf Lothar III, protected by Archbishop Adalbert von Mainz , prevailed . who was crowned king on September 13, 1125. In this case, too, the Speyer people held on to the Staufer antagonist, who later became Konrad III, and again a Speyer bishop, Siegfried II von Wolfsölden (1127–1146), was chased out of the city because he had held on to the Guelph. Speyer took in the Hohenstaufen and they made the city, as described in the imperial chronicle , their "houbetstat", their most important base. In 1128 King Lothar and Archbishop Adalbert besieged Speyer, which must have been completely walled at that time, but in the course of which it had to surrender to starvation. This dispute underscored Speyer's military and political importance.

Lothar III. stayed in Speyer twice, 1135 and 1136, for a long time. After his death in 1138 the Hohenstaufen came with Konrad III. to power. This continued the policy of the Salians in Speyer, which u. a. in the further existence of the common Palatinate with the bishops and the important function of the cathedral school as Reich Chancellery was expressed. The emperors could still be sure of the support of the Speyer bishops, who held the highest imperial offices. The cathedral school developed into the "Diplomatic School of the Reich" and many clergymen of the cathedral monastery were in the service of the Reich Chancellery.

The sermons of Bernhard von Clairvaux at Christmas 1146 in Speyer Cathedral moved Conrad III, who was staying at a Reichstag in Speyer, to take part in the Second Crusade . Four sandstone plates with brass writing in the nave of the cathedral commemorate this event.

Under his nephew, Friedrich Barbarossa , Heinrich V's privilege of 1111 was confirmed and extended in 1182. It is the oldest document in the Speyer city archive. In contrast to the Speyer people, the residents of the bishopric outside the city walls remained subjects of the bishop and were subject to the laws of serfdom and inheritance law until modern times . Barbarossa, who considered the Speyer Cathedral to be his last resting place, did not return from the Third Crusade in 1190 . His second wife, Empress Beatrix of Burgundy , and his little daughter Agnes were buried in the cathedral in 1184. Beatrix had brought the Free County of Burgundy (Franche-Comté) into the marriage as a dowry .

The successor to Barbarossa was his son, Heinrich VI. , whose reign was marked by the confrontation with the church, opposition princes and the breakaway Sicily. In December 1192, the English King Richard the Lionheart , who in the autumn of 1190 in Sicily a against Emperor Henry VI. directed support contract with the illegitimate ruler Tankred, captured on the way back from the 3rd crusade near Vienna and on March 25, 1193 at the Reichstag in Speyer to Heinrich VI. to hand over. On the opening day of the Reichstag (March 22, 193), there was a memorable rhetorical argument between the emperor and his prisoner, which ended unexpectedly in the reconciliation gesture of an embrace. In spite of all this, the emperor enforced his demands and the Speyer Treaty stipulated a ransom of 100,000 silver marks (around 23 tons of silver). It was presumably at this Reichstag that he granted the city the right and freedom to elect a council of twelve citizens from among its number. The document has not been preserved, but this right was confirmed in January 1198 by Philipp von Schwaben in a contract with the city of Speyer. With the obvious consent of the bishop, Philip legitimized the council constitution, which also prevailed in Lübeck , Utrecht and Strasbourg at the turn of the century . This privilege represented a further important step towards becoming a town and underlined the emperor's interest in strengthening the bourgeoisie. It is particularly noteworthy that the twelve councils were not appointed by the bishop and did not have to take an oath on him. If the election of the councils was not already in practice, this privilege represents the hour of birth of the Speyer city council. Heinrich VI. died in Messina in 1197 at the age of 32 and was buried in the Cathedral of Palermo .

Henry VI. three-year-old son could not take over the inheritance, whereupon a fight between the Staufers and Welfen for the rule of the king broke out ( German throne dispute ). In the aforementioned contract of January 1198, Speyer again sided with the Staufers and concluded a mutual aid alliance with their candidate, Philipp von Schwaben , the youngest brother of Heinrich VI. In the same year, the Staufer party elected Philip as king, while the supporters of the Guelphs elected Otto IV of Braunschweig . In the spring of 1199, pro-Hohenstaufen princes gathered in Speyer and on May 28th wrote a protest note denying the Pope the right to participate in the German election, let alone declare it lawful and Innocent III. called for no further violations of the rights of the empire in Italy. The princes threatened to come to Rome to enforce Philip's coronation as emperor. Unimpressed by this, Otto IV received from Innocent 1201 the approval of his coronation with the promise to cede territories in Italy to the church ( Neusser Oath ). In the same year Otto besieged Speyer, where his opponent, King Philip, was staying. In 1205 Philip held a court day in the city. The power struggle tended in favor of Philip, who, however, fell victim to a murder in Bamberg in 1208 in which the Imperial Chancellor and Speyer Bishop, Konrad von Scharfenberg (1200 to 1224), was personally present. Otto IV, now generally recognized as king, tried in December 1208 to get Speyer out of the Hohenstaufen camp with an extensive confirmation of privileges. On March 22, 1209 he renewed the Neuss oath of 1201 to the Pope in the Treaty of Speyer , which he never kept.

From 1207 important offices of the city were occupied by citizens and since then the council has kept its own seal . With these privileges Speyer continued to occupy a pioneering position in the empire. In the further course of the 13th century, the role of the city council strengthened and from the middle of the century the city council developed into a city court.

Frederick II , the son of Henry VI, managed to wrest power from Otto IV when he was of legal age. In 1213 he had the body of his murdered uncle, Philipp von Schwaben, transferred to the cathedral during a court day in Speyer. Under Frederick's reign, the cathedral school became the Reich's diplomatic school. The Speyer bishop Konrad von Scharfenberg accompanied him to Rome in 1220 for the imperial coronation. A first time for this year Hospital of the Teutonic Order is in Speyer. In 1221 the Franciscan Caesarius von Speyer began his mission in Germany.

The 13th century in Speyer was to be marked by the dispute over the rights of the city rulers. At the beginning of the 13th century there were increasing signs of an increasingly independent city council and that the council constitution took on institutional forms. In 1220 the city council is registered as universitas consiliariorum , in 1224 as consiliarii Spirensis cum universo eorum collegio , in 1226 and 1227 the first contracts in its own name, e.g. B. with Strasbourg. Eventually, jurisdiction passed from the church to the city. During the contest for the throne of Frederick II, the cities were encouraged to pursue a more independent policy. Around the mid-twenties, Speyer formed a city league with the cities of Mainz, Worms, Bingen, Frankfurt, Gelnhausen and Friedberg. However, this was banned on the court day of the new regent Duke Ludwig of Bavaria in November 1226, mainly at the instigation of the clergy princes. With the consent of the bishop, the council issued the first Speyer town charter in 1230, which dealt with violations of the town's peace. Two mayors were named for the first time. In 1237 the city council appeared as an independently acting institution under the name Consules et universi cives Spirenses .

In the 13th century, many orders founded monasteries in Speyer: In 1207, the Denkendorf Monastery took over the Holy Sepulcher Monastery near the Thieves Bridge in the suburb of Altspeyer, which had been administered by a women's convent . In 1212 Cistercians from Eusserthal established a branch on the site of today's Wittelsbacher Hof , after the Cistercians from Maulbronn Monastery had received the Maulbronner Hof on Johannesstrasse a few decades earlier . In 1228 the penitents from St. Leon settled in the city, who were later affiliated to the Dominican order at their own request; her St. Magdalena monastery is the oldest in Speyer today. A Franciscan monastery was built on today's Ludwigstrasse by 1230, in 1230 German rulers took over a religious house with a hospital on the site of today's consistory, and in 1262 the Dominicans came , to whom today's Ludwigskirche on Korngasse goes back. Around the middle of the century, Augustinian hermits began building a monastery on the site of today's district and city savings bank (former Siebertsplatz, now Willy-Brandt-Platz). In 1294 the Carmelites completed a monastery at today's Postplatz. In 1299 Clarissen came from Oggersheim to Speyer, who expanded a courtyard in the area of today's St. Klara-Kloster-Weg to the St. Klara-Kloster . Many monasteries maintained courtyards in the cities as bases for trade; in Speyer alone there were 19 monastery courtyards, twelve of which belonged to Cistercian abbeys.

The city expanded again due to strong influx: in 1232 the suburb of Hasenpfuhl was first mentioned. At the end of the century, the first mint in Speyer was created on the site of the old town department store Alte Münze today .

In the escalating dispute between the emperor and the church, Speyer again took sides in 1239 for Friedrich II, who was banned for the second time, and his eleven-year-old son Konrad. This led to open hostility with the bishops Konrad V. von Eberstein and from 1245 with Heinrich von Leiningen as well as with the Speyer clergy, who represented the Pope. In 1247 Frederick II ordered the clergy to be expelled from Speyer; however, it is not known whether this succeeded. The papal-minded clergy could no longer feel safe in Speyer. This was the first time that tensions between the city and the church emerged, which became apparent with the growing independence of the city council from the beginning of the 13th century. Despite the political independence, the sources of income remained almost entirely in the hands of the bishop, which is why the city council had no means of directing the city's fortunes.

In a certificate from July 1245, Friedrich II granted Speyer the privilege of a fortnightly autumn fair, which was to be spread in numerous cities. Trade fairs held an excellent position in the economic life of the Middle Ages and were a core part of the economy of that time. Friedrich justified this policy with the general benefit of promoting the exchange of goods. The Speyer autumn fair from Simon and Judas was important for the Electoral Palatinate , the diocese and for the Neckar area to Heilbronn. For this purpose, the city issued invitations to all cities and those involved in action in the empire, in which, as an encouragement, the tariff was reduced by half for the participants. Exceptions were Utrecht , Cologne , Trier and Worms , important trading partners of Speyer, with whom special regulations existed. What is remarkable about this invitation is that the city arbitrarily took the right to lower the tariffs. Today's Speyer autumn fair goes back to this fair. In long-distance trade, Speyer remained completely oriented towards Frankfurt , which could also be reached by water.

The Speyer Cathedral Chapter

The old cathedral chapter (capitulum) of the prince-bishopric was an ecclesiastical body with around 30 clergy and various duties towards the church. The economic basis of the cathedral chapter were foundations and donations, such as B. the Zehnthof in Esslingen . The chapter essentially supported the bishop in the administration of the diocese, but represented an independent institution with its own statutes and rules and was not subject to episcopal control. It elected the bishop and represented him in his absence. Over time, the chapter was consistently occupied by the nobility and in 1484 the Pope even determined that only the nobility may be admitted as members. The cathedral chapter owned goods that were also not under the control of the bishop. Heinrich III, who presented several foundations in 1041 and 1046, even did so on the condition that the bishop is excluded from the administration. Every canon or canon (canonicus capitularis) was entitled to a benefice or an income and was obliged to live near the cathedral. The chapter was headed by the provost (praepositus), the highest office after the bishop. From the end of the 12th century, the leadership went to the cathedral dean (decanus).

The old cathedral chapter represented an important economic factor in the city, as it had facilities such as wine cellars, barns, granaries, workshops, bakeries, etc., in which cathedral vicars (vicarii) carried out their activities under the supervision of the cathedral chapter. There were about 70 cathedral vicars in connection with the Speyer cathedral. Therefore, the cathedral chapter in Speyer played an important role in the struggle for power in the city.

Subordinated to the cathedral chapter and led by a cathedral chapter, the chair brotherhood , was the Speyer chair brotherhood , a community of lay people who prayed daily in the cathedral for the rulers buried here and lived in their own benefice houses.

- The library of the cathedral chapter

Three libraries were associated with the cathedral: the cathedral library with the liturgical books as part of the cathedral treasury, e.g. B. the Speyer Gospels (Codex Aureus Spirensis), the Palatinate Library of the Bishop (from approx. 1381 in Udenheim) and the Library of the Cathedral Chapter, the largest of the three libraries. In his praise of Speyer (Pulcherrimae Spirae summique in ea templi enchromata) in 1531, Melanchthon's pupil, Theodor Reysmann , noted that this library is located in a room that adjoins the assembly room of the cathedral chapter on the upper floor of the east wing of the cloister and that whose main entrance was secured by an iron door (Enchromata, lines 785-810). Another access to the library was possible through a door in the cloister, which led to a spiral staircase, which in turn led directly into the library ( Hern d (octor) Balthasar Feldman Vic (arius) is approved, he can have a key to the snail, so now in the Creutzgang hienuff in the Liberej ). From the minutes of the cathedral chapter of February 11, 1503 it emerges that books were lost and in future no lending should be allowed without the knowledge and consent of the chapter ( item one should also renew the order of the book (s) r halves, and that further no book about the libery is to be taken, it is done then with will and my lords know about the chapter ). Some books were chained. Such requests were almost always denied.

In August 1552 troops of the Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach, Albrecht Alcibiades (1522–1557), occupied the city and looted the cathedral and the adjacent buildings. Archival material was lost and the books were brought to the nearby house of the Teutonic Order, where they were packed. Albrecht had in mind to give the books to his stepfather, the Count Palatine von Neuburg (later Elector Palatinate), who had always kept an eye on them. This did not happen because the troops had to leave the city hastily. It is not known whether all of the books were returned to the library.

One of the most important manuscripts in the library was an anthology from the 9th or 10th century with around a dozen ancient and early medieval works on geography, transport and administrative history, which was lost after 1550–1551. All known and existing copies of the Notitia Dignitatum , a unique document of the Roman imperial chancelleries and one of the very few surviving documents on late antique administration, are derived either directly or indirectly from this Codex Spirensis . The Notitia was the largest document in the Codex.

Escalating dispute between the city and the clergy

The second half of the 13th century was marked by violent disputes between the city and the bishop, and above all the monasteries , which were only exacerbated by the investiture dispute. The four Speyer collegiate monasteries, Domstift, St. German, Weidenstift and Dreifaltigkeitsstift, succeeded as "the ecclesiae Spirenses , as an alliance representing the entire priesthood of the city" to argue for power with the bishop and council and represented an important power factor in the City. They did not shy away from falsifying their own history in order to achieve their goal. The pens and the bishop did not always pull together.

It was the cathedral chapter in particular that developed into the actual adversary of the citizenship. There were always mutual threats, economic sanctions, punitive and countermeasures affecting taxes and revenues. On the one hand, the church did not want to forego income and, on the other hand, did not want to pay taxes to the city. Citizens refused to pay the church for this. For example, Bishop Beringer threatened those citizens with the ban if they did not pay their interest to the Speyer canons. The power struggle between Pope and Emperor had an impact on these conflicts from outside. While the citizenry sided with the emperor, the clergy stood with the pope. The emperor and the pope granted their partisans privileges. The city received the Speyerbach back from Friedrich II in 1242. The permission for the autumn fair in 1245 can also be seen in this light. The Popes Gregory IX. and Innocent confirmed possessions to the cathedral chapter in 1239 (church in Heiligenstein and Deidesheim) and in 1244 extensive rights. On July 30, 1246, Pope Innocent even took people and possessions of the cathedral church under his special protection. Emperor Friedrich II then ordered the clergy to be expelled from Speyer. It is not known if this was implemented.

After the deposition of Frederick II by Pope Innocent IV in 1245 and especially after Frederick's death in 1250 and the death of his successor, Conrad IV. In 1254, a period of uncertainty and unrest began that lasted until Rudolf I was elected in 1273 . In July 1254, Speyer merged with 58 other cities to form the Rhenish League of Cities and Princes , which proclaimed a general land peace for a period of ten years in order to overcome the uncertainty during the interregnum . Agreements on tariffs were also made here. Due to their strengthened position of power, the cities were able to have their good behavior towards the king and pope rewarded with confirmations of privileges, such as from William of Holland in 1254 and 1255 and Richard of Cornwall in 1258. However, the alliance dissolved again in 1257. In 1258, Speyer agreed with Worms to recognize the ambiguous election of Alfonso of Castile as German king instead of Richard of Cornwall, who was also elected. Should Alfons not accept the election, Speyer and Worms would vote for another king.

In the middle of this century it is documented for the first time that there is “public property” in Speyer in the form of municipal property. In 1259, a donation from councilor and mint house mate Ulrich Klüpfel of goods and rights in Böhl and Iggelheim created the basis for the first civic foundation, the "Spital".

In the opinion of the pens, the bishops had shown themselves to be too indulgent in the erosion of the rights of the church towards the city. This met with vehement resistance from the city's four monasteries, especially the cathedral chapter, who felt they were affected by the unmoney collection by the citizens. On April 1, 1262, Bishop Heinrich II had given the city the right to “Ungeld” (taxes on wine) for a period of five years. In return, the city council renounced the free council elections, which it had long been granted. Nevertheless, this concession by the bishop went too far for the four foundations and in 1264 they united against this agreement. The trigger for this was that the citizens of Speyers u. a. The monastery clergy had destroyed buildings and plantings and the church faced harassment. As a countermeasure, the monasteries decided that neither councilors, other citizens, nor their relatives up to the fourth generation, could become canons or brothers of the Speyer Church or receive a benefit . In spite of these threats, the payment of the cash and other taxes was still refused. In the following year there was finally an uprising of some councilors and citizens in 1264/65, who also turned against the compliance of the council to the bishop, and not only the collegiate clergy, but also the episcopal court, citizens and Jews were exposed to violence. This rebellion represented the first open and serious resistance of at least part of the Speyer citizenship against the bishop and the clergy. The leaders, along with their families and helpers, were banished from the city in December 1265, but were accepted by the Count of Leiningen . The tension between clergy and citizens continued to smolder. On November 1st, the imperial immediacy of the city of Speyer was confirmed. Speyer was seen as a shining example for other cities in terms of the freedoms it gained . Pope Clement IV, in turn, in 1268 confirmed all previously promised privileges for the Speyer Church, which also included freedom from secular taxes.

In 1273, shortly after his election , King Rudolf I of Habsburg held a court day in Speyer, where he renewed the privilege of Friedrich Barbarossa from 1182 to his citizens and campaigned unsuccessfully for the restitution of the exiled insurgents. Under Rudolf I, Speyer served as a model for the founding of cities and city surveys. B. Neutstadt (1275), Germersheim (1276), Heilbronn (1281) or Godramstein (1285). With Otto von Bruchsal , the provost of Guido pen was another Speyer Court Chancellor of the King.

In 1275 the city treasurer tried to bring the cathedral clergy to a secular court, whereupon the ban was imposed on him in 1276. However, this was of no consequence as he remained a member of the city council. In addition to the disagreements about the unmoney, there was also the serving of wine and the church's taxes on grain exports. Due to the church's refusal to pay taxes, the city imposed an export ban. On Good Friday 1277, the spokesman for the monasteries, cathedral dean Albert von Mussbach , was murdered. The murderer or murderers were not caught, possibly even covered by the city. The Pope demanded an investigation into the complaints of the Speyer church and the city extended measures against the clergy. Citizens were banned from buying wine from the church. Bakers were no longer allowed to grind their grain in church mills. In addition, the city began to build two towers next to the cathedral and the houses of the canons. In 1279, the pens complained to the Pope that the city required them to pay a purchase and sales tax, had banned citizens from buying wine in their homes and exporting wine and grain to avoid market and sales fees. On April 13, 1280, the bishop was forced to give in to the city. He swore to respect all of the city's privileges in future, which was the first time that he unconditionally recognized the city's freedoms. The city then set about securing its power by obliging knight Johannes von Lichtenstein to serve in the war against all its enemies for one year. Lichtenstein left a third of the Hohenstaufen castle Lichtenstein (Pfalz) and the Kropsburg to the city . The city's four monasteries took this as an opportunity to join forces again to defend their rights and freedoms.

The monasteries could not expect any support from the bishop for their concerns towards the city and in 1281 renewed their alliance to defend their rights. The economic war between the city and the clergy came to a head. From the revenge of King Rudolf on October 21, 1284 it emerges that the ban on the export of grain was renewed after the clergy wanted to sell grain outside the city at higher prices. The city also banned the clergy from buying and importing wine, which the clergy wanted to use to undercut the city's price and make a profit. Citizens refused to pay the "small tithe" to the church, and construction of the two towers continued. The clergy then left the city and the bishop imposed an interdict in vain . He also dismissed the episcopal office holders and dissolved the courts, whereupon the office holders were replaced by citizens. As part of the revenge, a compromise was finally reached, but this did not resolve the conflict. The serving of wines and jurisdiction were left out. Therefore, the city decided in 1287 that council members were not allowed to hold a number of offices on the side: chamberlain , mayor , bailiff , mint master and customs officer , which excluded the bearers of the most important episcopal offices from the council.

Rudolf I died on July 15, 1291 in Speyer and was buried in the cathedral. The sculpture on his grave slab shows a lifelike image of the king, which was created shortly after his death and is considered an outstanding artistic achievement of this time.

Speyer becomes a Free Imperial City

In 1293 Speyer concluded an "eternal" alliance with the cities of Worms and Mainz to assert their rights against their bishops and the king. In September 1294, the council under the mayors Bernhoch zur Krone and Ebelin filed a solemn protest against the bishop's presumptuous approach in front of the cathedral. This protest was read out in all Speyer churches. On October 31 of the same year, Bishop Friedrich and the city council signed a treaty that met the city's long-standing demands in all essential points and laid down the end of episcopal power. Citizens were with their goods from duties and taxes, the "bitter gas" (duty to provide accommodation), from the spell of wine , the army control , collections , Prekarien exempt and other services. The bishop filled courts and offices at the suggestion of the council. In the future he was not allowed to arrest clerics or lay people without proof of guilt. A regulation should be found with regard to the sale of wine. This treaty also contained a passage that described the banishment of the rebellious citizens in 1265 as unjust and their heirs were allowed to return to the city. This ended the tense rule of the bishops and Speyer became a free imperial city , but the dispute over the special rights of the monasteries was not yet settled.

In connection with the disputes between the city and the clergy, there is one of the oldest evidence of the Carnival in Germany. In the Speyer chronicle of the town clerk Christoph Lehmann from 1612, who reports from old files, it says: “In 1296, the mischief of the Carnival started a little early / in it a number of burgers in a hiding place with the Clerisey servants carried away the worst / afterwards This is a difficult matter to be attached to the council / and the wrongdoers to be punished. ”(Clerisey Gesind means the servants of the bishop and the cathedral chapter , i.e. the clergy ). The chaplains accused a number of council members and citizens of various acts of violence, e.g. B. violent entry into the courts of cathedral clergy, into the ecclesiastical immunity area around the cathedral and physical attacks on church servants. Obviously, there is talk of assaults, which the cathedral chapter took as an occasion for a lawsuit against the council and citizens of Speyer and threatened with excommunication . However, due to the determined response from the city, the matter petered out, and it is telling that even such a threat did not deter citizens from such actions.

On February 2nd, 1298, Bishop Friedrich promised to impose an excommunication, an inhibition or an interdict only after proper summons and conviction. The pens' displeasure turned against the bishop, and they continued to oppose the loss of their privileges. Mediation by the Archbishop of Mainz did not come about until 1300. In the meantime, the city received further rights from King Adolf . According to a document from 1297, King Adolf took the citizens of Speyer and Worms under his protection. In return, the two cities agreed to support the king. The citizens were given the right to be prosecuted only in their own city. In addition, they received the diverted Speyerbach back, and in 1298 they received the income from the city's Jews. In the battle of Göllheim on July 2, 1298, a contingent from Speyer took part on the side of Adolf against Duke and Anti-King Albrecht von Habsburg . Adolf was killed in the process. Albrecht was confirmed as king shortly afterwards. In Speyer he quickly found an ally in his conflict with the Rhenish electors; as early as February 1299 he confirmed the privileges of the city, which became his preferred residence. In 1301 he officially gave the citizens the right to collect the unpaid.

Despite the mediation of the Bishop of Mainz, the disputes continued due to minor incidents. After the death of Bishop Friedrich, Sigibodo II von Lichtenberg , a partisan of King Albrecht, was elected as his successor. However, he had to assure the Speyer clergy in an "election surrender" that he would revoke the concessions to the city. In addition, a force of 60 mounted mercenaries was set up to fight against the citizens. The city denied entry and homage to the new bishop, and rather prohibited the sale of wine by and interest payments to clergy. As a result, there were armed conflicts for over seven months, and the area around Speyer and the courtyards of the church were devastated. On October 4, 1302, the warring parties concluded a treaty in which almost all of the citizens' demands were granted. It even remained with the ban on serving wine by clergy. This left the bishops only with the rights that they had already negotiated with Bishop Friedrich in 1294. Their sphere of influence was limited to the area of cathedral immunity , which is why it was also called cathedral city. There were two independent political rulers within the city walls.

Housemates and guilds

In the 14th century the generalis discordia , the dispute between the citizenry and the clergy, played only a subordinate role. In the Wittelsbach-Habsburg throne dispute, Speyer was again at the center of imperial politics. Against this background, a power struggle developed between the Münzer household members and the guilds over the occupation of the council .

The emergence of an urban leadership class was originally a side effect of the episcopal city rule. From the noble and bourgeois servants as well as experienced and wealthy citizens, an administrative patrimony arose , which was of decisive importance for the early days of urban development. Thanks to their long-standing monopoly in monetary transactions, the Münzer household had developed into a highly influential group with excellent contacts to royalty. From the 1270s onwards, the merging of the administrative patronage with merchants, the local nobility of the area and, above all, the Münzer house members, created a new leadership class, which was particularly characterized by its economic power.

The beginnings of the guild system are not documented in Speyer. When they were first mentioned at the beginning of the 14th century, they were already characterized by a high level of organization. Cloth production played a key role in Speyer, for which reason the madder dye plant was cultivated in the area . It is certain that the guild bourgeoisie had by far the largest share of the Speyer population. Properly organized professional groups in Speyer were bakers / millers, fishermen, gardeners, farmers and butchers, who make up about a third of all mentions in documents. Textile production and services (trade, wine bars, transport, market traffic) are each named with around a fifth. There was also fur and leather processing and trading, the construction industry, metal processing and, last but not least, municipal servants and supervisory staff. Some of the trades were increasingly or only represented in certain urban areas: the Lauer in the west of the Hasenpfuhlvorstadt, the Hasenpfühler around the port area on the Speyerbach, the gardeners in the Gilgenvorstadt, the fishermen in the Fischervorstadt. The guild houses of shopkeepers, shoemakers, Brontreger, old clothes and blacksmiths were grouped south, those of bakers, butchers, Salzgässer, tailors, winemakers, weavers, clothers and stonemasons north of the large Marktstrasse (today Maximilianstrasse), with a focus on the Salzgasse / Fischmarkt and Greifengasse.

Due to increasing pressure from the guilds, the council change of 1304 resulted in a contract on the future composition of the Speyer council. In the future, this should consist of 11 members of the household and 13 representatives of the guild, with each group having a mayor. By clever tactics, however, the members of the household managed to keep the council in their hands again until 1313.

King Heinrich VII held a court day in Speyer in 1309, where he performed a symbolic act: on August 29, he left the bodies of Adolf von Nassau and Albrecht von Habsburg , who had faced each other as enemies in the Battle of Göllheim in 1298 In 1309 they were solemnly buried next to each other in the cathedral. The last two kings found their resting place in the Speyer Cathedral and at the same time made it the largest collection of royal tombs in Germany. The following year, on September 1, 1310, he had his fourteen-year-old son, Johann von Luxemburg, married Elisabeth in Speyer .

In 1313 epidemics and hunger crises broke out across Europe, from which Speyer was not spared.