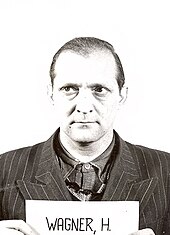

Horst Wagner (diplomat)

Horst Wagner (born May 17, 1906 in Posen , † March 13, 1977 in Hamburg ) was a German diplomat in the Third Reich . He was best known as the head of the "Inland II" department responsible for "Jewish affairs" in the Foreign Office and as a liaison between the National Socialist Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler . In these functions, Wagner was jointly responsible for the deportation of Jews and war crimes . He was one of the organizers of the propagandistic rejection of an initiative known as Feldscher-Aktion from May 1943 to save thousands of Jewish children and is considered to be the initiator of the conference of Jewish advisors in Krummhübel in April 1944. He evaded criminal prosecution initially by fleeing to South America and later by systematically Delaying the pending criminal proceedings against him.

Live and act

Youth, Education, and Early Years

Wagner's father, Johannes, came from a family of officers and was a military officer in Poznan when his son Horst was born. After attending a secondary school in Berlin-Steglitz , which he left in 1923 without a high school diploma , he began a traineeship at the Berlin export company Neuhof und Jonas , which he finished after only six months. After he was subsequently awarded the university entrance qualification by an examination commission of the Reich Ministry of Education, Wagner studied history and international law at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin . He also took a few courses at the German Political College . According to his own information, Wagner studied with interruptions at the German University for Physical Education from 1925 and obtained a diploma there in 1929, which his biographer Sebastian Weitkamp exposed as a fake . He also stated in an interrogation after 1945 that in 1936/1937 he had tried to do his doctorate with a "Professor Dofi" (probably Emil Dovifat ), which, however, was not temporarily possible.

From 1930 to 1936 Wagner drew with the name Horst M. Wagner as a sports journalist and freelancer for various publishers and newspapers, including for Ullstein , the Berliner Tageblatt and Wolffs Telegraphenbüro . In this position he made numerous trips abroad to report on sporting competitions and international sporting relations. In an interrogation in 1947, he stated that at the time he was “probably one of the best-known names in the sports press”, which was denied by other journalists. In addition, even though he was only a third-rate tennis player, Wagner “made himself available as a tennis partner for a fee”. He met his future wife Irmgard at the Rot-Weiß Berlin tennis club ; they married in Cottbus in 1935 .

In 1931, Wagner was also employed by the Reich Committee for Physical Exercise for nine months, where he was responsible for editing yearbooks and sports badges. Around 1935 Wagner - who spoke French, English and at least some basic Spanish - also worked for a few months in the “Civil Air Protection” department of the Reich Aviation Ministry as a lecturer and interpreter for foreign newspapers.

Career in the diplomatic service of the NS state

From the beginning of 1936 Wagner tried to get a job in the Foreign Office, where he was put on the list of candidates. As an alternative, he applied to the Ribbentrop Office, the Foreign Office of the NSDAP , where he initially claimed to have been rejected - allegedly because he did not belong to either the party or a party organization and because his father was the head of a Berlin Masonic lodge .

In the run-up to the 1936 Olympic Games , Wagner was then offered by the head of the England department in the Ribbentrop office , Karlfried Graf Dürckheim , to look after prominent English guests during the games. After accepting this offer, he joined the Ribbentrop office on May 1, 1936 as an international sports attaché. Since he had successfully looked after well-known English personalities such as Lord Beaverbrook during the Olympic Games , Wagner continued to work as a companion for English guests in the office. Later he was employed in the England Department and in Main Department VI, which is responsible for press and archive work. In his Nuremberg interrogation on June 19, 1947, Wagner stated that he had been commissioned in 1937 to "found the German-English booklet and to lead it as chief editor", a bilingual magazine of the Ribbentrop office in cooperation with the British Embassy in Berlin , which, according to Wagner, "was published by me in the German publishing house and intended for Germany". Six issues of this magazine have appeared. His biographer Sebastian Weitkamp only mentions in this context that Wagner tried to take over the management of the German-English Society in mid-1937 . But this attempt failed.

After Ribbentrop was appointed Reich Foreign Minister on February 4, 1938, Wagner followed him to the Foreign Office in February 1938, where he initially worked as a research assistant in the protocol department under Alexander von Dörnberg . His tasks there included the preparation of state receptions, thanksgiving, invitations, gift matters, and congratulatory telegrams. In 1939 Wagner was assigned to the personal staff of the Reich Foreign Minister. In this position he was appointed Legation Councilor in 1940 , and in 1943 as Legation Councilor. From 1940 to 1945 Wagner was also entrusted with the management of the Wiesenhof Stud, which was part of the Foreign Office. As part of this activity, one of his tasks in the occupied part of France was to procure riding horses for the Reich Foreign Minister and to bring them to the stud.

"Liaison leader" between Ribbentrop and Himmler

Wagner joined the NSDAP in 1937 ( membership number 5,387,042) after he had been admitted to the SS the year before , where he rose to SS-Standartenführer on January 1, 1944 . While Wagner stated to his best man and his wife as a motivation for his service in the Foreign Office that it had always been his ideal to become a diplomat, his biographer Weitkamp sees him more as an opportunist, who with his connection to Ribbentrop under all circumstances and with wanted to seize his last professional opportunity with the greatest adaptive behavior. He tried to compensate for his lack of professional qualifications with reliable allegiance to the Nazi ideology and hoped that his "membership of a Nazi organization, especially the emerging SS, would give himself a significant career boost".

Until the end of the war, Wagner acted as head of the “Inland II” group of the Foreign Office, in which four, and from late summer 1944 five, presentations were combined. The tasks of these lectures ranged from the recruiting of ethnic German "volunteers" for the Waffen SS in Southeast Europe to the integration of selected SD agents and Jewish officers in diplomatic missions to the diplomatic safeguarding of the preparation and implementation of anti-Jewish measures in Southeast Europe, from 1944 mainly in Hungary . In addition, in April / May 1943 he was initially appointed by Ribbentrop as liaison officer of the Foreign Office to the SS and then, in return, appointed by Himmler as his sole liaison officer to the Foreign Office. Wagner's liaison activities based on this double assignment consisted primarily in the mutual communication and coordination of the wishes and suggestions of Himmler and Ribbentrop as well as in the implementation of the foreign policy and anti-Jewish measures agreed between the two heads of department.

"Feldscher-Aktion" 1943 and conference of the "Judenreferenten" in Krummhübel 1944

When the Swiss envoy Peter Anton Feldscher asked the Foreign Office on May 12, 1943, on behalf of the British government, whether there was a willingness to allow 5,000 Jewish children from the German territory to travel to Palestine , Wagner let Eberhard, the Foreign Office's Jewish advisor, report to him Von Thadden worked out a propagandistic rejection of this rescue attempt, which was known in official jargon as Feldscher-Aktion , for the Inland II group, which he himself supported and approved by various department heads of the Foreign Office .

According to the verdict of the Wilhelmstrasse Trial of April 11, 1949, Wagner signed a memorandum dated June 25, 1943 and written by Thadden, which served as the basis for the later propaganda rejection. After that:

"England [...] declare its willingness to allow the Jews to enter England instead of Palestine, and should prove this willingness by a corresponding resolution of the House of Commons; it was to be expected that the English would not comply with these demands, and then the responsibility would rest on them; but should England unexpectedly agree, then this process can be evaluated propagandistically and give Germany the opportunity to propose the exchange of Jews for interned Germans. "

At the end of 1943, Ribbentrop commissioned Wagner to set up a central anti-Jewish propaganda center in the Foreign Office, which was initially founded as “Information Center X” and then functioned as “Information Center XIV (Anti-Jewish Foreign Action)”. SS-Hauptsturmführer Heinz Ballensiefen and SS-Untersturmführer Georg Heuchert worked as representatives of the Reich Security Main Office . Wagner appointed Rudolf Schleier , who had previously worked at the German embassy in Paris, as his representative for the management of this “information center”, which was to “centrally manage anti-Jewish propaganda abroad”, among other things by means of a central collection and distribution of anti-Jewish texts, the Establishment of a “Jewish and Anti-Jewish Archive of the Foreign Office” and the planning of corresponding conferences.

In January 1944, Wagner proposed that a working conference should be called in which the Jewish advisors of the foreign missions of the Foreign Office and the " Aryanization advisers " of the SS should take part in order to improve their cooperation, because, according to Wagner, the

"Necessity of increased work, especially in the field of foreign information regarding the Jewish question."

He asked Ribbentrop's approval of his proposal, which he gave, so that

"Wagner can therefore be considered the initiator of the conference, which pursued the goals of coordinating and optimizing the work of the 'Aryanization consultants' with the propaganda campaigns and of establishing the new unit as an auxiliary instrument between the SS and the AA."

The conference took place on April 3rd and 4th in the Lower Silesian town of Krummhübel as a prelude to an “anti-Jewish action point” or “anti-Jewish foreign action”. Franz Alfred Six demanded the "physical elimination of the Eastern Jews", as Thadden recorded. Other well-known participants in the campaign were Harald Leithe-Jasper , Adolf Mahr , Gustav Richter , Heinz Ballensiefen , Hans-Otto Meissner as consul in Italy, Peter Klassen , Paris and Hans Hagemeyer .

Crimes against American prisoners of war and the French general Mesny

According to a report in the Berliner Zeitung , Stasi documents from the 1970s were found in 2010 that put a considerable burden on Wagner: According to this, he had been involved in war crimes against American prisoners of war by arranging for them to be sentenced to death in violation of international law at Ribbentrop's request. Wagner noted for Ribbentrop on December 31, 1944:

"In connection with the conviction of 15 German prisoners of war by American courts-martial for their actions against fellow prisoners, the Fuehrer approved the proposal of Mr. RAM (Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop) to bring about the immediate sentence of a corresponding number of American prisoners of war to the death penalty."

According to Wagner's report, ten US soldiers were sentenced to death between December 28 and 30, 1944, and another death sentence was pending. Three days later, Ribbentrop's wish was completely fulfilled, thanks to the efforts of the officers responsible, who had even interrupted their Christmas vacation for the war crime. Wagner asked Ribbentrop for a commendation on January 3, 1945:

"In the conviction of American prisoners of war brought about on the instructions of Mr. RAM [...], various gentlemen [...] earned special merits [.]"

Ribbentrop suggested that those responsible should be uttered "occasionally [...] some words of appreciation [...] in the name of Mr. RAM orally in a suitable manner".

As the personal liaison of Himmler and Ribbentrop, Wagner was involved in the planning for the murder of the French general Gustave Mesny , who was a prisoner of war in Germany . The murder of a French general was requested by Adolf Hitler after the German General Fritz von Brodowski , one of those responsible for the Oradour massacre , was shot dead by the FFI in an attempt to escape while in French captivity under unexplained circumstances . In cooperation between the Reich Security Main Office , the head of the prisoner-of-war system and the Foreign Office, Mesny was selected as the victim and shot by SS men during a transport when a car broke down. On behalf of Ribbentrop, Wagner and the legal department of the Foreign Office ensured that the crime was planned in such a way that it could be concealed under international law if necessary.

post war period

At the end of the Second World War , Wagner and several other diplomats were arrested by American troops in Bad Gastein, Austria, and taken to a prison in Salzburg by collective transport . Due to the system of automatic arrest for functionaries from party and state, he was "transferred to the American occupation zone " and finally " brought to Nuremberg after an odyssey through allied camps on August 28, 1946 ". According to the historian Ernst Piper , Wagner met Emilie Edelmann, who had been arrested as an “important witness in the trial against the SS Race and Settlement Main Office ”, and with whom he had a love affair until 1954, while in Nuremberg imprisonment . Their daughter, the writer Gisela Heidenreich , presented the story of Wagner as a Nazi perpetrator and lover of her mother in a mixture of real traces and literary representation.

Since archaeological finds after the war revealed the proportion of senior officials of the Foreign Office and in particular of Wagner's "Inland II" department in the persecution measures against European Jews, charges were to be brought against him in the Wilhelmstrasse trial . When the list of accused was expanded to include members of other agencies based on Wilhelmstrasse, Wagner's name was deleted. Instead he was now brought as a witness and questioned by Robert Kempner . In the first place he was questioned about the murder of General Mesny and blamed Himmler, Hitler and Ribbentrop. Interrogated about his role as head of the Inland II group in the persecution of the Jews, "he characterized himself as a postman who only delivered messages".

Wagner took the witness stand at the Wilhelmstrasse trial on March 3, 1948. Based on his precise knowledge of the incident, Kempner hoped that Wagner would give a reliable testimony against the defendant Karl Ritter , ambassador for special use at the Foreign Office. In contrast to Wagner, Ritter was charged with participating in the plans for the murder of Mesny, as he was responsible for “monitoring the execution of the murder assignment”. But Wagner turned out to be worthless as a witness for the prosecution. In contrast, Ritter's defense attorney, Erich Schmidt-Leichner, succeeded in “portraying Wagner as actually responsible”.

Around Christmas 1947, Wagner was transferred to the Nuremberg-Langwasser internment camp , which also detained people who were later to be transferred to the German judiciary. For such cases of anticipated lawsuits that the Americans no longer wanted to conduct under their own direction, they set up a transition department called the Special Projects Division within the framework of their investigative authority, the Office of Chief of Counsel For War Crimes (OCCWC) , with which they were still outstanding Wanted to transfer proceedings into German jurisdiction. Wagner was listed among those who are likely to be accused in the future in the “highest group A”. In July 1948, a report by the "Special Projects Division" stated that Wagner and Thadden had made themselves a criminal offense during the deportations of Jews from Slovakia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania and the Netherlands because they "fully approved the SS measures" would have. On August 11, 1948, the OMGUS authorized the German courts to exercise jurisdiction in the criminal case against Franz Rademacher , Wagner, von Thadden and Karl Klingenfuß . Wagner fled "from the weakly guarded camp" on August 25, 1948, got to Italy and finally to South America via one of the rat lines .

In 1952 Wagner returned to Italy under a false name as a correspondent for Argentine newspapers. After his exposure, he was tried there; an Italian appellate court ruled in 1958 not to extradite him to Germany. At the end of 1958 he came to Germany voluntarily. A preliminary judicial investigation began in Essen. Wagner was imprisoned for around 15 months until the Hamm Higher Regional Court released him on bail in March 1960 . The indictment of the Essen public prosecutor's office (AZ 29 Ks 4/67) is dated February 22, 1967. The first day of the main hearing was scheduled for May 20, 1968 at the Essen regional court ; he was charged with complicity in the murder of 356,624 Jews. A trial against Wagner, initially defended by Ernst Achenbach , did not materialize: after a postponement of the proceedings was unsuccessful, Achenbach resigned as a "calculated emergency brake" on May 8, 1968 and Wagner's new legal representatives, Hans Laternser and Fritz Steinacker, had to settle in work in the files. After Laternser's sudden death, Fritz Steinacker, who was still involved in another Nazi case, took over the 20 volumes of files and 20,000 documents alone. New reports of sickness - confirmed, among other things, by reports from the Hamburg psychiatrist Hans Bürger-Prinz - delayed the proceedings until it was temporarily suspended in 1974 due to the defendant's inability to stand trial. It came to an end with Wagner's death on March 13, 1977. The Nuremberg Prosecutor Robert Kempner, who was involved as a joint plaintiff in these proceedings against Wagner, wrote in retrospect to the then Federal Minister of Justice Hans-Jochen Vogel in 1978 :

"This file is almost a textbook on how a procedure can be put off after years of input and then end up with a medical certificate."

literature

- Eckart Conze , Norbert Frei , Peter Hayes , Moshe Zimmermann : The Office and the Past. German diplomats in the Third Reich and in the Federal Republic. Karl Blessing Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-89667-430-2 (also series of publications, vol. 1117, the Federal Agency for Civic Education . Bonn 2011).

- Hans-Jürgen Döscher : The Foreign Office in the Third Reich. Diplomacy in the shadow of the “final solution”. Siedler, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-88680-256-6 , pp. 262–305 (paperback edition: SS and Foreign Office in the Third Reich. Diplomacy in the shadow of the “final solution”. Ullstein 1991, ISBN 3-548-33149- 1 , Simultaneously Hamburg, Univ., Diss., 1985).

- Gisela Heidenreich : Seven years of eternity. A German love. Droemer Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-426-27381-4 .

- Gisela Heidenreich: Beloved perpetrator. A diplomat in the service of the “Final Solution”. Droemer Verlag, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-426-27432-3 .

- Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats. Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the “Final Solution”. JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, ISBN 978-3-8012-4178-0 .

- Johannes Hürter (Red.): Biographical Handbook of the German Foreign Service 1871–1945. 5. T – Z, supplements. Published by the Foreign Office, Historical Service. Volume 5: Bernd Isphording, Gerhard Keiper, Martin Kröger: Schöningh, Paderborn et al. 2014, ISBN 978-3-506-71844-0 , p. 154 f.

Web links

- Literature by and about Horst Wagner in the catalog of the German National Library

- Institute for Contemporary History : Archive - Find aids online. Inventory Behm, Hans-Ulrich. Signature ED 411. On the holdings: files for the preliminary investigation against the former Legation Councilor in the Foreign Ministry of the Inland II Department, Horst Wagner (PDF; 127 kB), plus materials and additional documents in the area, for example the investigation into the "Mesny case", the murder of the French general Gustave Marie Maurice Mesny in January 1945. See also IfZ signature Ge 01.07 and Ge 01.02 for further holdings on Horst Wagner and Mesny.

- Institute for Contemporary History : Witness literature online. Wagner, Horst. ZS – 1574 (PDF; 16.3 MB). Minutes of some of Wagner's interrogations from 1946/1947 at the IFZ

- War crimes. Pain not measurable . In: Der Spiegel . No. 42 , 1972, p. 55-57 ( Online - Oct. 9, 1972 ).

Individual evidence

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 43.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 47, see also Hans-Jürgen Döscher: The Foreign Office in the Third Reich. Diplomacy in the shadow of the final solution. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1987, p. 265, footnote 10.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Döscher: The Foreign Office in the Third Reich. Diplomacy in the shadow of the final solution. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1987, p. 265.

- ↑ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats. Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the “Final Solution”. JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 46 and p. 445.

- ↑ a b Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats. Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the “Final Solution”. JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 49.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 41.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 53.

- ↑ a b Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 54.

- ^ Institute for Contemporary History : Testimonies online. Wagner, Horst. ZS – 1574, p. 82. (PDF; 16.3 MB)

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Döscher: The Foreign Office in the Third Reich. Diplomacy in the shadow of the final solution. Pp. 264–276, especially pp. 268 ff. (Facsimile of Wagner's personal form in the Foreign Office of October 19, 1944).

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Döscher: The Foreign Office in the Third Reich. Diplomacy in the shadow of the final solution . Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1987, 266.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Döscher: The Foreign Office in the Third Reich. Diplomacy in the shadow of the final solution. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1987, pp. 264–276, here p. 272. (Facsimile of Wagner's personal sheet in the Foreign Office of October 19, 1944).

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 53 u. P. 57 (quote).

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 106.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, pp. 120-133.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, pp. 209-230.

- ^ The judgment in the Wilhelmstrasse trial. The official wording of the decision in case no. 11 of the Nuremberg Military Tribunal against von Weizsäcker and others, with differing reasons for the judgment, corrective decisions, the basic legal provisions, a list of court officials and witnesses. Introductions by Robert MW Kempner and Carl Haensel. Alfons Bürger Verlag, Schwäbisch Gmünd 1950, p. 103; see. also Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the “final solution”. JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 218.

- ↑ Eckart Conze, Norbert Frei, Peter Hayes and Moshe Zimmermann: The office and the past. German diplomats in the Third Reich and in the Federal Republic. Munich 2010, p. 195 ff.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 275 f.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 276.

- ↑ Eckart Conze, Norbert Frei, Peter Hayes and Moshe Zimmermann: The office and the past. German diplomats in the Third Reich and in the Federal Republic. Munich 2010, p. 197 ff.

- ^ According to the list of participants in the April 1944 SS-AA conference .

- ↑ a b c d Andreas Förster: With the deferral of legal concerns ( memento from November 2, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: Berliner Zeitung , October 28, 2010, accessed on February 28, 2012.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 331.

- ↑ Volker Koop: In Hitler's hand. “Special prisoners and honorary prisoners” of the SS. Böhlau, Cologne 2010, p. 115 f.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: "Murder with a clean vest" The murder of General Maurice Mesny in January 1945. In: Timm C. Richter (Ed.): War and crime. Martin Meidenbauer Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-89975-080-2 , pp. 31-40, here pp. 31 f .; comprehensive Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, pp. 327-368, in particular pp. 358 f.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 371.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 371 u. P. 377.

- ↑ Ernst Piper: The mother's silence. Love for a mass murderer . Gisela Heidenreich researches her life story. In: Der Tagesspiegel , December 22, 2011.

- ↑ Gisela Heidenreich: Seven years of eternity. A German love. Droemer Verlag, Munich 2007; Gisela Heidenreich: Beloved perpetrator. A diplomat in the service of the “Final Solution”. Droemer Verlag, Munich 2011.

- ↑ Dirk Pöppmann: Robert Kempner and Ernst von Weizsäcker in the Wilhelmstrasse trial . For the discussion about the participation of the German functional elite in the Nazi crimes. In: Irmtrud Wojak, Susanne Meinl: In the labyrinth of guilt. Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-593-37373-4 , p. 173.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 379.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 380.

- ↑ a b Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 382.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 384.

- ^ Edith Raim: Justice between dictatorship and democracy. Reconstruction and prosecution of Nazi crimes in Germany 1945–1949. Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-486-70411-2 , p. 617.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 385 u. P. 387 f.

- ^ Biblioteca nazionale centrale Roma

- ↑ a b war crimes. Pain not measurable . In: Der Spiegel . No. 42 , 1972, p. 55-57 ( Online - Oct. 9, 1972 ).

- ^ A b c Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 433.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 438.

- ^ Sebastian Weitkamp: Brown diplomats: Horst Wagner and Eberhard von Thadden as functionaries of the "final solution". JHW Dietz, Bonn 2008, p. 439.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wagner, Horst |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German diplomat in the Third Reich |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 17, 1906 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Poses |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 13, 1977 |

| Place of death | Hamburg |