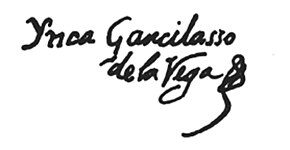

Inca Garcilaso de la Vega

El Inca Garcilaso de la Vega ("El Inca"; * April 12, 1539 in Cuzco , Peru , as Gómez Suárez de Figueroa ; † April 23, 1616 in Córdoba (Spain) ) was a Peruvian writer and recognized chronicler of the history of the Inca as well as the conquest of Peru by the Spaniards .

life and work

Origin and youth

El Inca Garcilaso de la Vega was the son of the Spanish conquistador Capitán Sebastián Garcilaso de la Vega y Vargas (approx. 1500–1559) and a niece of the Inca ruler Huayna Cápac ( Wayna Qhapaq ), called Isabel Suárez Yupanqui , née Chimpu Ocllo ( Uqllu ). Gómez 'father came from the noble, extreme Ricohombre family of Suárez de Figueroa and was a nephew of the then very famous poet Garcilaso de la Vega († 1536). His father's relatives included other well-known Renaissance poets such as Jorge Manrique († 1479) and the Marquis of Santillana († 1458). The boy grew up in the house of a Spanish friend in Cuzco with his two younger siblings, Garcilaso and Leonor, with his mother, was raised bilingual in Quechua and Spanish and enjoyed together with other descendants of the Inca rulers and the leading conquistadors in the former Inca capital excellent training. On his mother's side, his grandfather Huallpa Túpac Yupanqui (1481–1533), as a full brother of the Inca, held a prominent position in the imperial administration, and a great-uncle and various former Inca officers frequented the house of the Palla ("noblewoman") Chimpu Ocllo and mediated the children her knowledge. His uncle Francisco Huallpa Túpac Yupanqui, his mother's younger brother, also lived in the house and was later in contact with Inca Garcilaso when he was already living in Spain.

In 1542 they moved to their own house in the central Plaza Cusipata while their father was active in the city government. The 9-year-old Gómez experienced the turmoil of the civil war (1544–1548) when the house was besieged for days by enemy conquistadors in the absence of his father and the family threatened with death. After the restoration of order by the royal appointed President of the Audiencia , Don Pedro de la Gasca , Sebastián Garcilaso de la Vega separated from his Indian partner, to whom he was not officially married like practically all conquistadors, and married the Spanish Luisa Martel de los Ríos, with whom he had more children. This corresponded to the policy of the Spanish Council of India at that time, which was characterized by strict moral concepts and the pro-racism of the blood purity ideology prevailing in Spain and wanted to put an end to the irregular connections between the Spanish ruling class and Indian women. According to official doctrine, the mixing of Spaniards and indigenous people was seen as a danger to the future development of the colony. El Inca Garcilaso de la Vega criticizes this behavior of his father, which he had to witness when he was about 12 years old, later in the VI. Book of his Comentarios (1609) quite open.

Emigration and early work

After his father's death in 1560, when he was just under 20, he traveled to Spain , as his father had bequeathed him money on the condition that he should study in Spain. Once there and well received by his father's relatives - especially in Montilla in the house of his uncle Alonso de Vargas y Figueroa († 1570), who became a father figure to him after arriving in 1561 - he tried to assert certain privileges at court which, in his opinion, belonged to him as the eldest son and - in his opinion - heir to a Spanish nobleman who belonged to the first generation of conquistadors and who had even been governor ( corregidor ) of Cuzco from 1554 to 1556 . However, he was refused because of his alleged involvement in the anti-crown rebellion of Gonzalo Pizarro . In any case, only the younger half-siblings born in wedlock could inherit the paternal inheritance.

After initial disappointment, he applied for a return trip to the Viceroyalty of Peru in 1563 , but kept postponing his departure until a son was born to him and his own mother had married another Spaniard in distant Peru. In the end he never returned to America. From 1564 he hired himself as a soldier, took part in the suppression of the Morisk uprising (1568–1571) in the Sierra Nevada under Juan de Austria and was promoted to royal captain . He did not continue his military career but moved to Montilla and began to write - financially secured by his uncle, who bequeathed his house to him. He initially worked on translations and wrote various smaller poetic works, but apparently from the beginning he was concerned with the idea of documenting the memories of the lost Inca empire for posterity. Meanwhile his mother had died in 1571. For reasons that have never become quite clear and are probably related to the identity crisis triggered by his origin and the move to a completely alien world, he changed his name several times and finally called himself El Inca Garcilaso de la Vega , taking the name of his father combined with the title designation, which expressed his noble parentage on his mother's side. He did this although he had initially fought to be recognized as the full heir of his father, knowing full well that the presumptuous title "Inca" was not his (it was only allowed to call himself Inka, whoever came directly from the male line Ruling dynasty). In the opinion of Remedios Mataix, the well-known poet's name and the exotic title secured him the necessary attention within a society that was foreign to him and at the same time gave him the outsider role that made his literary existence as a reporter from a world completely unknown to the Spaniards possible.

Garcilaso owned a chapel that his uncle had procured for him, and in 1579 received minor ordinations as a cleric . Another church career was out of the question due to his illegitimate origins. His first literary work was a translation from Italian of the Dialoghi d'amore des León Hebreo , which was published in Madrid in 1590. The work dedicated to King Philip II was the first printed book by a Peruvian author in Spain. Garcilaso used the work on this almost encyclopedic work of Renaissance Neoplatonism to practice elegance and style and to deepen his general knowledge. After the death of his aunt, he settled in Córdoba in 1591 and gained access to the local humanist circles. He bought a well-stocked library and read and commented on the works in it extensively. El Inca Garcilaso spoke Latin well, studied historical works by Plutarch and Julius Caesar as well as the contemporary chronicles of the discovery and conquest of America and read the Italian poets popular at the time, such as Ariost or Boccaccio . As the first book dealing with the New World, Garcilaso published a chronicle of Hernando de Soto's voyages of discovery in Florida ( La Florida del Inca ) in 1605 , for which he compiled the reports of various informants. In the description of the voyages of discovery through Inca Garcilaso, some interpreters recognize covert attacks on the politics of Spain in Peru, in whose conquest Hernando de Soto, together with Francisco Pizarro and the author's father, also took part.

Working as a historian

His main work, the "Truthful Commentaries on the Incas" ( Comentarios Reales de los Incas ), announced and prepared since 1586 but only published in Lisbon in 1609 , he wrote from the memory of the oral traditions known to him from his family and education supplemented by information that he obtained from relatives and acquaintances living in Peru. His aim was to use the history of the Inca to bring the Andean reality closer to the Spanish reader from their mythical origins to the victory of Atahualpa ( Atawallpa ) over his half-brother Huáscar ( Waskar ). The book ends with the defeat of the Inca Huáscar, who was legitimate from Garcilaso's point of view, and the subsequent bloodbath that Atahualpa caused among the relatives and supporters of his rival to the throne on the eve of the conquest of the empire by the Spaniards and from which Garcilaso's mother had only narrowly escaped. The place of publication of the work is explained by the dedication to the Duchess of Bragança , Princess Catherine of Portugal (1540–1614), a granddaughter of King Manuel I of Portugal .

Around 1612/13 he completed the second part of the Comentarios, the “General History of Peru” ( Historia General del Perú ), in which the events of the conquest of Peru by Francisco Pizarro , the civil wars between the conquistadors and the fate of the descendants of the Inca rulers up to Execution of the last Inca king Túpac Amaru (1572) are described. This work was published posthumously in Córdoba in 1617, the year after his death. Some interpreters see the first part of his comments as a homage by the Incas to his mother and her family, while in the second part he deals with his father's role in the turmoil and disputes after the Conquista and tries to explain and justify his behavior (Don Sebastián Garcilaso had a reputation for disloyalty, as he is said to have changed his party often; among Peruvians he was nicknamed "the faithful for three hours"). Based on this interpretation, some consider the first part of his main work as an indictment against the unfaithful father, which presents itself as a protest by the Inca against the robbery of his homeland, while in the second part a reconciliation with the father takes place, which with the incas Garcilaso in his new Spanish homeland.

He devoted the last years of his life to the revision of a poetry banned by the Inquisition by his ancestor Garci Sánchez de Badajoz († 1526), whose family history and genealogy he had already written down in 1596 at the suggestion of a friend. The controversial work, the Liçiones de Job apropiadas a las pasiones de amor , was a parodic travesty of the biblical Book of Job ; and El Inca - as a cleric himself in the ecclesiastical service - tries to repackage the most intrusive passages into a form acceptable to church censorship.

The Inca Garcilaso de la Vega died on April 23, 1616 at the age of 77. He was buried in a side chapel donated by him in the Cathedral of Córdoba and had his epitaph provided with a grave inscription he wrote himself.

At the time of the uprising of José Gabriel Condorcanqui in the eighteenth century, the publication of the Comentarios Reales in Lima by Charles III. prohibited due to their "dangerous content". The book was not reprinted on the American continent for the first time until 1918, although individual copies were in circulation beforehand.

A peculiarity in the biography and work of Garcilaso, which distinguishes him from other chroniclers of the colonization of America, is that he has traced his Spanish roots back to the society of his father's origin and became part of an "old" culture that applies to him as well alien "new" had to appear as for the original discoverer the "New World" itself. As the only American-born writer of mestizo origin, he emigrated in the opposite direction and did not stay in colonial society and become part of it, but in the "old world" moved out. Although he is regarded as the mestizo par excellence in South American historiography , he can therefore hardly be regarded as a typical representative of Latin American mestizaje and compared with those Indian, mestizo or Creole authors who have always been part of colonial society and who never firsthand know the reality of continental Spain could take. With Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, therefore, there is less mixing than actual comparison of the Inca / Andean with the Hispanic / Occidental culture, without eliminating the contrasts in a new cultural context such as the Mestizaje . Nostalgia and homesickness for what has been lost, be it the lost culture of the Inca or the loss of the original homeland, are therefore more in the foreground in Garcilaso's work than with the historians living in the Creole environment.

Honors

The stadium in Cuzco ( Estadio Garcilaso de la Vega ) was named after him in 1950.

A university in Lima also bears his name.

Others

The historical novel The Sword and the Moon by Laura Pariani deals with the life of Inca Garcilaso de la Vega.

expenditure

- La Florida

- La Florida del Inca. Edition by Sylvia L. Hilton (ed.), Historia 16, Madrid 1986.

- La Florida del Inca. Edition, Einf. U. Note from Sylvia L. Hilton (critical edition), Fundación Universitaria Española, Madrid 1982.

- La Florida del Inca. Historia del adelantado, Hernando de Soto, governador y capitán general del reino de la Florida, y de otros heroicos caballeros españoles e indios. Lisboa 1605. Facsimile, Extramuros Edición, Mairena del Aljarafe (Sevilla) 2008, ISBN 9788496784185 .

- The Florida of the Inca: a history of the Adelantado, Hernando de Soto, governor and captain general of the kingdom of Florida, and of other heroic Spanish and Indian cavaliers. Austin (Texas) 1951 (English).

- History of the conquest of Florida, translated from the French by Heinrich Ludewig Meier. Cell, Frankfurt, Leipzig 1753 ( digitized in the Google book search).

- Comentarios reales

- Comentarios reales de los Incas. Edition by Héctor López Martínez (ed.), Orbis Ventures, Lima 2005.

- Comentarios reales de los Incas. Edition, Einf. U. Note from Mercedes Serna (critical edition), Castalia, Madrid 2000.

- Comentarios Reales de los Incas. Edition by Carlos Araníbar (ed.), Fondo de Cultura Económica, Ciudad de México 1991, ISBN 968-16-4892-7 ; most recently: 2005, ISBN 968-16-4893-5 .

- Comentarios reales (selection). Edition and introduction by Enrique Pupo-Walker (arr.), Colección Letras Hispánicas, Cátedra, Madrid 1990.

- Royal commentaries of the Incas and General history of Peru / by Garcilaso de la Vega, El Inca (The Texas Pan American series). Trans. U. Einf. V. Harold V. Livermore. University of Texas Press, Austin 1987 (English).

- Garcilaso de la Vega: Truthful Commentaries on the Inca Empire. German v. W. Plackmeyer. 2nd edition Berlin, Rütten & Loening 1986.

- Complete digital copies of the Comentarios reales

-

Download option at Memoria Chilena :

- Part 1 ( Comentarios reales ; PDF, 163 MB)

- Part 2 ( Historia General del Perú ; PDF, 237 MB)

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Sagrario Arenas Dorado, Anna María Lauro: Suárez de Figueroa, Gómez [cronista español] (1539-1616). Short biography of the online encyclopedia MCNBiografías (Micronet, San Sebastián de los Reyes ) (span.).

- ↑ a b Cf. Remedios Mataix, author's biography.

- ↑ So suspected (inter alia) Remedios Mataix (University of Alicante) in the author biography of the Cervantes Institute linked below .

- ↑ a b Cf. Max Hernández: Memoria del bien perdido: Conflicto, identidad y nostalgia en el Inca Garcilaso de la Vega ( Memento of the original from November 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (= Colección Biblioteca Peruana de Psicoanálisis 15). 2., corr., Revised by the author. u. exp. Ed., Lima 1993, ISBN 84-89303-23-1 (first edition Madrid 1991), which presents a psychoanalytic interpretation of the figure of Inca Garcilaso de la Vega.

- ↑ Berta Ares Queixa: El Inca Garcilaso y sus “parientes” mestizos. In: Carmen de Mora, Guillermo Seres, Mercedes Serna (eds.): Humanismo, mestizaje y escritura en los Comentarios reales. Iberoamericana / Vervuert, Madrid / Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 978-8484895664 , p. 15.

- ^ Universidad Inca Garcilaso de la Vega

- ↑ Review by Henning Klüver ( Deutschlandfunk ) from July 13, 1998, accessed on January 9, 2016.

Web links

- Literature by and about Inca Garcilaso de la Vega in the catalog of the German National Library

- Literature by and about Inca Garcilaso de la Vega in the catalog of the Ibero-American Institute of Prussian Cultural Heritage, Berlin

- Author biography of Remedios Mataix in the Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes (span.)

- Books by and about the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega in the catalog of the SUB Göttingen

- Excerpt from True Commentaries on the Inca Empire (German by Wilhelm Plackmeyer, 1983) (PDF file; 1.45 MB)

- Bibliography on Inca Garcilaso de la Vega by Juan G. Gelpí, Seminario de Estudios Hispánicos, Puerto Rico (25 pages, PDF file; 151 kB)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Inca Garcilaso de la Vega |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Suarez de Figueroa, Gomez; Garcilaso de la Vega, El Inca; El Inca de la Vega; El Inca Garcilaso |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Peruvian poet and writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 12, 1539 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cuzco , Peru |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 23, 1616 |

| Place of death | Cordoba (Spain) |