Jakob Boehme

Jakob Böhme , contemporary Jacob Böhme , (* 1575 in Alt-Seidenberg near Görlitz ; † November 17, 1624 in Görlitz) was a German mystic , philosopher and Christian theosophist . Hegel called him the “first German philosopher” because he was the first to write philosophical works in German.

Life

Jakob Böhme was born as the fourth child of an owning farming family. Father Jakob was a parish clerk and magistrate. Because of his weak constitution, the boy was apprenticed to a shoemaker. After years of traveling , Jakob Böhme settled in his hometown of Görlitz as a shoemaker in 1599, acquired citizenship and bought a shoe bank on the Untermarkt. In the same year he married Katharina Kuntzschmann and bought a house on the Töpferberg. His wife bore him four sons between 1600 and 1606. During this time he had at least three mystical experiences , which he did not initially make public.

In 1612 he recorded his thoughts in handwriting in a work later called Aurora or Dawn in the Rise - astonishing work for a simple shoemaker who had never studied. All the seeds of his later thinking are found in this work. Böhme himself gave it the name Morgenrot (the title Aurora , by which it was later known, is the Latin translation of this name).

Böhme had no intention of publishing this work and only gave it to his friends to read. But the manuscript was copied and distributed without his knowledge. The then main pastor of the Görlitz Peter and Paul Church , Gregor Richter , to whose congregation Böhme belonged at the time, saw a copy. Richter considered the work heretical and took action against Böhme at the city council. Thereupon Böhme was briefly arrested and banned from writing. After a few years of silence, in 1618 he was persuaded by friends to write again and now with the self-assurance of someone called. In the meantime he had familiarized himself with the work of Paracelsus and with the philosophy of Neoplatonism , and his talent for writing had developed fruitfully. His second work The Description of the Three Principles of Divine Essence (De tribus principiis) appeared in 1619. Together with his wife, he began to operate a yarn trade.

After the publication of Weg zu Christo (1624) and some other writings, Richter became active again and prepared another indictment. Despite Richter's death on August 24, Böhme was increasingly exposed to hostility from the community. He dealt with his critics in the Theosophical Letters , which aroused great interest in his growing following. While still on his deathbed, Böhme had to face a faith interrogation. Richter's successor initially refused the "heretic" a Christian burial, which was eventually carried out. The agitated residents defiled his grave in the Görlitz Nikolaikirchhof .

Contemporary environment

The philosophy of Böhme is characterized by an idealistic pantheism , which is strongly occupied with materialistic elements. His worldview corresponds to the early bourgeois views. Böhme was shaped by the turmoil of the time, such as the aftermath of the Reformation and the Peasants 'War , the solidification of Protestantism and the Counter-Reformation , which had been gaining ground since the 1660s, and the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War. In a narrower sense, it was Protestantism, persisted in rites and dogmas, which determined large areas of intellectual and practical life in Germany, against which Boehme's teaching was directed.

It was an expression of the petty-bourgeois opposition, which also parts of the Lower Lusatian-Silesian nobility joined. The main intellectual sources to which this direction was based, was that of Nicholas of Cusa inaugurated pantheism of this nature influenced philosophical doctrine of Paracelsus and the Neo-Platonism and the Kabbala oriented mysticism of Agrippa of Nettesheim . The main representatives of this trend are Sebastian Franck , Valentin Weigel and Böhme, whose teaching represents its culmination and conclusion.

Böhme and his followers were dissatisfied with official Lutheranism and strongly oriented towards the teaching of Kaspar Schwenckfeld (1489–1561). Schwenckfeld wanted - a suggestion that was frequently encountered in opposition mysticism and based on early Christian ideals - Christianity without a church as a special hierarchically structured form of organization, because as a result, the closeness of man to the divine idea is dependent on his position within the hierarchy. Rather, he advocated a direct relationship of every person to the divine message.

If the external factors of Boehme's life are also known, then this cannot be said of his intellectual development and his relations to the contemporary theoretical mainstreams, since there is no information about them. Apart from the Bible, he did not quote other works, nor did he name authors. However, one can indirectly infer his direct sources from his writings. As a result, he knew the natural-philosophical, astrological, alchemical and religious-mystical literature of his time. He himself stated that he “read the writings of many great masters” without having found the spiritual peace he was striving for.

Think

Nature as a teacher

In his writing Aurora or Dawn in the Rise , Böhme explains that his true teacher is “the whole of nature”: “There is indeed good and bad in nature. Because all things come from God, evil must also come from God [...] The bitter quality is also in God, but [...] as an everlasting force, a triumphant source of joy, "which the sky, the stars, the Elements and makes the creatures mobile.

He studied all of its philosophy, astrology and theology from all of nature and its “standing birth” and not from people and through people. Nevertheless, the influence of "many high masters" is unmistakable, especially that of Paracelsus , Valentin Weigel and Kaspar von Schwenckfeld . Above all, Weigel's epistemology, which leads from the divine idea to man, - learning is to know oneself; let man learn the world, he himself is the world; Although all supernatural knowledge comes from the divine idea, it does not come without man, but in, with, from and through man - forms the theoretical background of Bohemian creativity.

Boehme's thoughts are not always obvious at first glance in his writings, but are intertwined with his mystical, fantastic, and in part with alchemical speculations. Böhme, who never went to university and had to acquire all of his knowledge himself, did not have an exact scientific language that operated on abstract terms. In spite of all the disadvantages that arise from this, the popular features emerged in his expressive and lifelike imagery, which brought him into unusually sharp, self-pronounced contrast to the current school and book scholarship. This was also due to the fact that his personal goal was not only philosophical-theoretical, but also prophetic-practical.

Key points of his thinking

Boehme's thoughts circle

- the pantheistic equation of nature and God,

- the derivation of both the principles of good and evil in nature "as an everlasting force" which "makes creatures mobile" (Aurora) from God,

- about the thought that the contradiction is present as a necessary moment in all phenomena of reality, admittedly without using the term itself, and thus about the dialectic of the qualities of the "angry" and the loving God in the creation of the world,

- about the importance of the feminine principle of wisdom (Sophia) for real knowledge and

- about the freedom of mankind that arises from the inner relation to the primordial ground.

pantheism

The principles of light and darkness that reveal themselves from the essence of God in nature and its creatures are omnipresent in life. Therefore, as formulated in The Way in Christ , “Heaven and Hell [...] are present everywhere. It is just an objection of the will either in God's love or in anger ”.

In Böhme one finds the same pantheistic motif again, even if not as a result of direct connection, which arose when considering the history of the matter-form problem (see hylemorphism ), with the central figures Averroes and Giordano Bruno , and through the gradual one The inclusion of “divine” reality in the conception of the material was characterized until finally, with Bruno, the matter in the first place sets the form out of itself.

The gap that Böhme thus opened to the official doctrine of Christianity could not be bridged despite all the assurances of orthodoxy and led to hostility against him.

Böhme felt with all severity the contradiction contained in traditional scholastic cosmology between the pure spirituality of the divine imagination and the “material”, “earthly” reality that it should have created. In no script can he find an answer to the tormenting question of which matter or force probably produced grass, herbs, trees, earth and stones. With this, the problem of creation was raised again by Böhme and thus, from his point of view, the question of the relationship between the spiritual and the material was raised anew.

God and Lucifer

If his social circumstances and the status of individual scientific research at the time are taken into account, it becomes understandable that his answers have a mystical character; at the same time they show dialectical moments. He went back to the idea of Lucifer, whose exaltation had aroused anger, "grimness" in God. That is why man does not find “divine” rest in nature, but rather “raging and tearing, burning and stabbing and a very reluctant being”, nothing “because vain grimness” (in: 1, Volume 2, 185, 171, 91 ). This "grimness" is not to be understood morally one-sidedly, but to be seen in connection with his doctrine of quality. Böhme contrasted Grimm as bad quality with good quality. Both are the aggregation of three special qualities or “source spirits”, whose opposing behaviors determine what happens in the world. Böhme does not see God as a pure spirit, rather this needs an "eternal nature" in order to be able to become a living spirit in the first place. The whole of nature stands in great longing, always willing to give birth to the divine power. She is the body of God and has all the strength as well as the whole birth. For Böhme "grimness" ( three principles of divine nature ) is the prerequisite for life and "mobility": "[A] uch would be neither color nor virtue, everything would be nothing". So duality is the engine of creation. In the Theosophical Letters it says: "Heaven is in hell and hell is in heaven". The dark side of this dynamic is, as Böhme explains in Vom Dreiffach Leben des Menschen (The Threefold Life of Man) , a “dispute in man and about man”: “There are two seekers in the soul, one always seeks earthly being, one is God's addiction and seeks heaven ". While nature remains “a fire”, “freedom is a light” and the goal of “another longing and desire for another being and life that is not animal and perishable”. In his book Vom Preten Böhme emphasizes that people have free will in their choice of kingdom: "People do what they want". Böhme gives a different answer to the old question of where and how evil came into creation than the church dogmatists, who assume a fundamental separation of the spiritual and worldly realms: Evil is a potential accompaniment of the natural force that emerges from God, which, however, is only realized through human decision-making. Böhme writes programmatically:

"[...], but if you want to talk about God what God is: you have to diligently consider the forces in nature, plus the whole of creation, heaven and earth, both stars and elements, and creatures, [...]"

In Aurora , Böhme explains that in connection with the quality of the “angry God” there is “hell, in addition to eternal enmity and the pit of murder, and such a creature [has] become the devil”, who in The Three Principles of the Divine Being was formerly “holier Angel "is represented, who in the" poor man [s] "through his" infectious poison [...] lets the fire of anger flare up and extinguish "the blissful light in the animal spirit". Like a murderer, Lucifer wanted to “bring everything under his power”, but the “fire of wrath of God in nature” does not “reach down to the innermost core of the heart, which is the Son of God, much less into the hidden holiness of Spirit ”that is permeated with love. Since Lucifer did not remain in love and extinguished it, his rule did not extend deeper ( Aurora ). The conflict between the two, the world of light and fear, "lasts as long as earthly life lasts" ( On the Incarnation of Christ ).

The concept of quality at Böhme

Böhme distinguishes between three phases in his conception of God and creation: In the first (and again in the third) section all forces rest as pure ideas, motionless and undivided in harmony of eternity: Böhme describes the way to Christ ("To the decision") in the text God as "in himself natureless, both affect and creatureless", without inclination, neither for good nor for evil. He [is] an “unground”, the “nothing and everything”, neither “light nor darkness, neither love nor anger, but the Eternal One”. Accordingly, he formulates in Aurora : "All forces in the father are in one another like one force, and all forces exist in the father in an inexplicable light and clarity." From this unity, Böhme explains the development to duality with the help of the qualities in a three-step reminiscent of the stages of dialectic.

Böhme's formulation of the term “quality” showed his considerable dialectical thinking ability. For him it meant agility, namely "to torment and do something". For him, “torment” as a driving movement was a basic quality of being. In his work De tribus principiis he then only used Grimm, overcoming the pair of terms “good and bad”, as the starting point for movement in reality. One can clearly find the idea of the existence of contradiction in things worked out: Everything "pushes, squeezes and enemies (itself) and therefore there is an aversion in the creature, and therefore every body is ourselves with itself" (in: 1, volume 3, preface, section 13).

The opposition between individual qualities is the prerequisite for the creation of the world: The “whole divinity in its innermost, most initial birth has a terrible sharpness at its core, in that the bitter quality [= second principle] is even a dark and cold contraction, like that Winter […] and the bitter quality [= first principle] is a raging and cutting bitter spring; because it divides and disperses the hard and bitter quality and makes the mobility. And between these two qualities the heat [= third principle] is born from its hard, fierce rubbing, tearing and raging, which rises as a fierce kindling. Such ascension is fixed in the harsh quality that becomes a body ”. If there were no other quality in this body that could erase the grimness, there would be constant enmity in it.

Böhme formulated the inseparable connection of the principle of contradiction that works in nature as follows:

- “For if there were no nature there would be no glory and power, much less majesty, and no spirit either; but a stillness without being, an eternal nothing without splendor and shine ”(in: 1, Volume 4, Chapter XIV, Section 37).

Sophia as the feminine side of the spirit

All of Boehme's works are pervaded by the endeavor to supplement the rationalistic thinking, which he regards as too one-sided and outwardly, with the powers of knowledge of heart, body and soul. He understands this as the feminine side of divine wisdom:

- "Every spirit is raw and does not know each other: now every spirit desires a body, both for food and bliss [...] The virgin of wisdom surrounded the soul spirit first of all with heavenly being, with heavenly divine flesh, and the holy Spirit gave the heavenly tincture. ”(Jacob Boheme: Forty Questions from the Souls. Question 4, paras. 1 and 6).

- “This is my virgin, whom I had lost in Adam because she became an earthly woman. Now I have found my dear virgin out of my body again. Now I will never leave them from me. The body is the soul's mirror and dwelling house, and is also a cause that the pure soul changes the spirit, as after the lust of the body or the spirit of this world. ”(Jacob Boehme: Forty Questions from the Souls. Question 7, para . 14).

In The Three Principles of Divine Essence , Sophia appears as a pearl-adorned virgin. Böhme explains in dialogue form, following the example of the biblical "Song of Songs", the tension in people between the "youth" as the "spirit that he inherited from nature from the world" and the "chaste virgin", the “spirit so blown into him from God”. The young man desired her as his bride, but she replied: “You are my bridegroom and my companion, but you do not have my jewelry […] my mind is always constant; but you have an unstable mind and your strength is fragile. Live in my courtyards; but I will not give you my pearl; because you are dark and it is light and beautiful ”. In her earthly marriage, "the noble Sophia [...] lost her pearl" ( The Way to Christ ) and became a woman who was also ruled by the spirit of this world. But the virgin, to whom he was always longing, has “promised not to leave [him] in no need: she wants to come to [him] to the aid of the virgin son, [...] he will probably come back into Bring Paradeis ”.

The idea of freedom in Böhme

The idea of freedom, which became decisive for classical German philosophy, found its justification for the first time in Böhme. Since the human being as a physical, mental and spiritual being is himself part of the eternal, divine or unground, he can also establish a reference to it in himself. Since the unground or the divine is unconditional, eternally free will and the origin of all things, the more he discovers this in himself, the more freer he becomes. So he can only relativize personally or socially determined things in and around himself and prefer the meaning of the whole, and thus also desire himself as a whole and free being:

- “First of all is eternal freedom, it has the will, and is itself the will. Now every will has an addiction to do or desire something, and in it he sees himself: he sees in himself in eternity what he himself is; he makes himself the mirror of his equals, then he looks at what he is: so he now finds nothing more than himself, and desires himself. "(in: Forty questions from the souls. Question 1, para. 13, The first figure).

In his work On Prayer , Böhme writes, “Man [has] free will, he [may] enjoy himself in a work on earth, whatever he [will]. Everything [stand] in God's miracle, man [do] what he [will] ”. In De signatura rerum he explains the connections between free decision-making and knowledge of nature. Because without them “a person could not understand the other”: “That is why the signature is the greatest understanding in which the person not only learns to know himself, but he may also learn to recognize the essence of all beings in it [...]. The whole outer world is a designation of the inner spiritual world […]. The essence of all beings is a struggling force, because the kingdom of God stands in the force, including the outer world ”. That is why everyone should learn to understand “how a life is ruined, how good becomes bad and bad becomes good when the will is turned around”, and get to know “what qualities reign in him. Man [must] be fighting against himself, if he wants to become a heavenly citizen "He should resist the four seductive" elements of the dark world "(pride, avarice, envy, anger) and consider," that God himself was his purpose in him, that he wanted to save him and introduce him into his kingdom ”( From six theosophical points ). He must “be born again if he wants to see the kingdom of God again” ( On the Incarnation of Christ ). This kingdom in its trinity “Father, Son and Holy Spirit” is “of eternal freedom and [remain] eternally freedom” ( From prayer ).

Aftermath

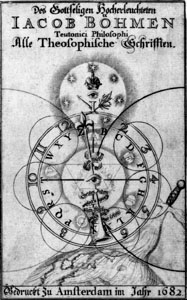

In 1682, Boehme's theosophical writings were published together for the first time.

Boehme's aftermath was evident in Germany and especially in the Netherlands and England, where the supporters of his ideas were called "Behmenists" , as well as in Sweden, Finland ( Lars Ulstadius , Peter Schaefer , Jakob Eriksson, Erik Eriksson, Jaakko Kärmäki and Jaakko Wallenberg ) and Russia. He found enthusiastic followers among the Quakers who carried his thoughts to America. Through Friedrich Christoph Oetinger , Böhme gained influence on Pietism in southwest Germany and through this on Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling . In 1809 Schelling donated Boehme's works to the Catholic theosophist Franz von Baader , which make an epoch in Baader's thought; Baader had been planning its own edition for years. Schelling also made Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel more familiar with Boehme's world of thought. In Boehme's speculations, Hegel praised the dialectical approaches contained in them, despite their “barbaric” language. He called him the "first German philosopher" because he was the first to write in German. Even Newton's theory of gravitation was associated with Boehme's “dialectic”. Böhme also influenced the early romantic poets and philosophers, especially Novalis , whose pantheistic nature symbolism is clearly inspired by Böhme. The romantic painter Philipp Otto Runge got to know Boehme's works through Novalis and was inspired by him for his daily cycle .

The French philosopher and mystic Louis Claude de Saint-Martin discovered Böhme for France. He was so enthusiastic about Böhme that at the age of almost fifty he learned German in order to be able to read his writings in the original. In doing so, he also brought about a Bohemian renaissance in Germany for the master who had since been forgotten there.

In his lectures on the philosophy of the Renaissance , the philosopher Ernst Bloch convincingly paid tribute to the "philosophus teutonicus" Jakob Böhme and placed him next to Paracelsus.

The depth phenomenology , which was founded by José Sánchez de Murillo , relies mainly on Jakob Böhme.

The sculptor Johannes Pfuhl created the bronze statue of the scholar, which was unveiled in the city park of Görlitz in 1898 .

The Evangelical Church in Germany commemorates Jakob Böhme with a day of remembrance in the Evangelical Name Calendar on November 17th .

On August 26, 2017 was in the Dresden chapel the exhibition ALL IN ALL. The world of thought of the mystical philosopher Jacob Böhme opens. The former sacred space is intended to represent "a walk-in building of ideas in which the ideas of the mystical philosopher Jacob Böhme can be clearly grasped".

Works (selection)

- 1612: Aurora (the dawn in the rise)

- 1619: De tribus principiis (description of the three principles of divine nature)

- 1620: De triplici vita hominis (Of the threefold life of man)

- 1620: Psychologica vera (Forty Questions of the Soul)

- 1620: De incarnatione verbi (Of the Incarnation of Jesus Christ)

- 1620: Sex puncta theosophica (Of six theosophical points)

- 1620: Sex puncta mystica (Brief explanation of the six mystical points)

- 1620: Mysterium pansophicum (thorough report of the earthly and heavenly Mysterio)

- 1620: Informatorium novissimorum (lessons from the last days to P. Kaym)

- 1621: Christosophia (The way in Christ)

- 1621: Libri apologetici (protective writings against Balthasar Tilken)

- 1621: Antistifelius (concerns about Esaiä Stiefel's book)

- 1622: In the same of the error of the sects Esaiä and Zechiel Meths

- 1622: De signatura rerum (Of the birth and the designation of all beings)

- 1623: Mysterium Magnum (explanation of the first book of Moses)

- 1623: De electione gratiae (Of the grace election)

- 1623: De testamentis Christi (Of Christ's Testaments)

- 1624: Quaestiones theosophicae (Contemplation of Divine Revelation)

- 1624: Tabulae principorium (tablets from the Dreyen Pricipien Divine Revelation)

- 1624: Apologia contra Gregorium Richter (protective speech against judges)

- 1624: Libellus apologeticus (Written responsibility to EE Rath zu Görlitz)

- 1624: Clavis (key, that is an explanation of the most distinguished points and words used in these scriptures)

- 1618–1624: Epistolae theosophicae (Theosophical Send Letters)

- 1682: editions of works

Modern editions of works

- Jacob Böhme: Complete Writings. 11 volumes, facsimile of the 1730 edition, ed. by Will-Erich Peuckert . Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1955–1989, ISBN 978-3-7728-0061-0 .

- Jacob Böhme: The originals. 2 volumes, published on behalf of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences . by Werner Buddecke. Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1963–1966, ISBN 978-3-7728-0073-3 .

Literature (selection)

Primary literature

- Werner Buddecke, Matthias Wenzel (ed.): Jacob Böhme: Directory of manuscripts and early copies. Municipal collections for history and culture, Görlitz 2000, ISBN 3-00-006753-1 .

- Werner Buddecke: The Jakob Böhme editions. Part 1: The editions in German. Reprint [1937] Topos, Vaduz 1981, ISBN 3-289-00233-0 .

- Werner Buddecke: The Jakob Böhme editions. Part 2: The translations. Reprint [1957] Topos, Vaduz 1981, ISBN 3-289-00256-X .

Secondary literature

- Bernhard Asmuth : Jakob Böhme. 1575-1624. In: Herbert Hupka (Ed.): Great Germans from Silesia. Gräfe and Unzer, Munich 1969, pp. 19-27.

- Günther Bonheim: Interpretation of signs and natural language. An experiment on Jacob Böhme. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1992, ISBN 3-88479-717-4 (also dissertation, University of Bonn 1989).

- Paul Deussen : Jakob Böhme. About his life and his philosophy. 2nd edition, FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1911.

- Gerhard Dünnhaupt : Jacob Böhme . In: Personal bibliographies on Baroque prints. Volume 1, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1990, pp. 672-702, ISBN 3-7772-9013-0 (list of works and literature).

- Frank Ferstl: Jacob Boehme - the first German philosopher. An introduction to the philosophy of Philosophus Teutonicus. Weißensee-Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-934479-57-X .

- Andreas Gauger: Jakob Böhme and the essence of his mysticism. 2nd edition, Weißensee-Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-934479-30-8 (also dissertation, TU Dresden 1994).

- Christoph Geissmar : The eye of God. Pictures of Jakob Böhme. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, ISBN 3-447-03453-X .

- Joachim Hoffmeister: The heretical cobbler. Life and thinking of the Görlitz master Jakob Böhme. Evangelical Publishing House, Berlin 1976.

- Maik Hosang : Jacob Boehme. The first German philosopher - The Miracle of Görlitz. Senfkorn-Verlag, Görlitz 2007, ISBN 3-935330-24-3 .

- Thomas Isermann: O security, the devil is waiting for you! Jacob Böhme readings. Oettel Verlag, Görlitz 2017, ISBN 978-3-944560-37-3 .

- Richard Jecht (Ed.): Jakob Böhme. Commemorative gift of the city of Görlitz on the 300th anniversary of his death. Magistrate, Görlitz 1924.

- Alexandre Koyré : La Philosophie de Jacob Boehme. Vrin, Paris 1929 (new edition 2002, ISBN 2-7116-0445-4 ).

- Dieter Liebig: Jakob Böhme: Aurora or Morgenröthe in the rise. A comment. Series of publications by the Herrnhut Academy, Volume 1. Neisse Verlag, Dresden 2012, ISBN 978-3-86276-077-0 .

- Ina Rueth: Jacob Böhme and the plague in Görlitz . Görlitz Theater, Görlitz 2007.

- Donata Schoeller Reisch: Elevated God - deepened man. On the meaning of humility, based on Meister Eckhart and Jakob Böhme. Alber, Freiburg i. Br. 2002, ISBN 3-495-47923-6 .

- John Schulitz: Jakob Böhme and the Kabbalah. A comparative work analysis. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1992 (original dissertation, Ann Arbor 1990).

- Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden , Claudia Brink, Lucinda Martin (eds.): Alles in Allem. The world of thoughts of the mystical philosopher Jacob Böhme - thinking · context · effect (catalog). Sandstein Verlag, Dresden 2017, ISBN 978-3-95498-328-5 .

- Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Claudia Brink, Lucinda Martin (eds.): Grund und Ungrund. The cosmos of the mystical philosopher Jacob Böhme (essay volume). Sandstein-Verlag, Dresden 2017, ISBN 978-3-95498-327-8 .

- Gerhard Wehr : Jakob Böhme. With testimonials and photo documents. 8th edition, Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-499-50179-1 .

- Matthias Wenzel : The mystic and philosopher Jacob Böhme (1575-1624). His way into the world - and back to Görlitz . In: BIS - the magazine of the libraries in Saxony. Volume 1, 2008, pp. 82-85, full text on Qucosa .

- Knowledge and Science - Jacob Böhme (1575–1624). International Jacob Böhme Symposium Görlitz 2000 (= New Lausitz Magazine . - Supplement; 2). Oettel, Görlitz and Zittau 2001, ISBN 3-932693-64-7 .

- Wilhelm Ludwig Wullen: Jacob Boehme's life and teaching. Liesching, Stuttgart 1836 digitized .

Articles in reference books

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : Boehme, Jakob. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 1, Bautz, Hamm 1975. 2nd, unchanged edition Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-013-1 , Sp. 661-665.

- Dibelius: Böhme, Jakob . In: Realencyklopadie for Protestant Theology and Church (RE). 3. Edition. Volume 3, Hinrichs, Leipzig 1897, pp. 272-276.

- Werner Buddecke: Böhme, Jacob. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 2, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1955, ISBN 3-428-00183-4 , pp. 388-390 ( digitized version ).

- Julius Hamberger: Boehme, Jacob . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 3, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1876, pp. 65-72.

Radio and film

- Aurora or dawn in the rise - Hommage à Jacob Böhme , radio play by Ronald Steckel , SFB, SWR, DRS Basel 1993

- Jacob Böhme, Philosophus Teutonicus - A journey in the footsteps of the first German philosopher , radio play by Ronald Steckel , SFB, SWF 1993

- Dawn in the rise - Hommage à Jacob Böhme , film by Max Hopp , Jan Korthäuer, Ronald Steckel and Klaus Weingarten, nootheater and organization for the conversion of the cinema in 2015

- Deutschlandfunk Love and Zorn - a long night about the mystic and theosophist Jacob Böhme by Ronald Steckel, 2020

Web links

- Literature by and about Jakob Böhme in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Jakob Böhme in the German Digital Library

- Publications by and about Jakob Böhme in VD 17 .

- Digitized prints by Jakob Böhme in the catalog of the Herzog August Library

- Jakob Böhme ( memento from February 21, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) in the Biographical Lexicon of Upper Lusatia

- Aurora or dawn in the rise, web edition

- Jakob Böhme Institute Görlitz

- Contents of the information boards from Jakob Boehmes' room in the Jakob-Böhme-Haus in Zgorzelec

- Rolf Beyer: "Dawn in the rise". The mysticism of Jakob Böhme. - SWR2 Wissen, broadcast on May 8, 2009 - for reading, listening (30 min) or downloading

- Consolation text of four complexions: this is instruction in the time of contestation for a constantly sad contested hertz [… Auff Begehren written in Martio Anno 1624 by Jacob Böhmeen], Amsterdam 1661, e-book of the University Library Vienna ( eBooks on Demand )

- Knowledge, notes and news about Jacob Böhme

- Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden: All in all. The world of thoughts of the mystical philosopher Jacob Böhme Special exhibition, August 26, 2017 to November 19, 2017.

- A long night about the mystic Jacob Böhme - Liebe und Zorn by Ronald Steckel, 2020

Individual evidence

- ↑ See also Ernst Benz : Der Prophet Jakob Boehme. A study of the type of post-Reformation prophethood (= treatises of the humanities and social science class of the Academy of Sciences and Literature in Mainz. Born in 1959, No. 3).

- ^ Karl Wilhelm Schiebler (ed.): Jakob Böhme, Sämmliche Werke . tape 2 : Aurora . Johan Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig 1832, p. 21 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Lectures on the philosophy of the Renaissance, part of the Leipzig lectures 1952–56. Suhrkamp Frankfurt / M. 1972, pp. 69-84.

- ↑ Jakob Böhme in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- ↑ ALL IN ALL. The mind of the mystical philosopher Jacob Böhme. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, accessed on August 24, 2017 .

- ↑ ALL IN ALL. Press release with pictures from the exhibition. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, accessed on August 30, 2017 .

- ↑ Ronald Steckel: Aurora or Dawn in the Rise - Hommage à Jacob Böhme - A piece for voices. HörDat .

- ↑ Jacob Böhme - Philosophus Teutonicus: A journey in the footsteps of the first German philosopher , Phonostar

- ↑ Dawn in the rise - Hommage à Jacob Böhme , nootheater.de

- ↑ Deutschlandfunk Liebe und Zorn - a long night about the mystic and theosophist Jacob Böhme by Ronald Steckel , accessed on April 13, 2020

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Boehme, Jakob |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Böhme, Jacob |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Shoemaker, mystic, natural philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1575 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Alt Seidenberg near Görlitz |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 17, 1624 |

| Place of death | Goerlitz |