Java rhinoceros

| Java rhinoceros | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Java rhinoceros in London Zoo (kept 1874 to 1885) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Rhinoceros sondaicus | ||||||||||||

| Desmarest , 1822 |

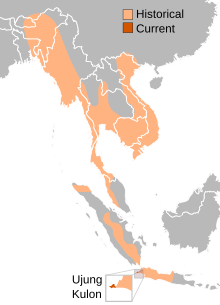

The Java rhinoceros ( Rhinoceros sondaicus ) is a single-horned rhinoceros native to Asia . It is closely related to the Indian rhinoceros ( Rhinoceros unicornis ) and is the rarest representative of the rhinos and thus one of the rarest large mammals . The species is only found in the west of the island of Java , in the Ujung Kulon National Park , with around 63 to 67 individuals. Originally, however, it was widespread in large parts of Southeast Asia and sometimes lived sympatheticallywith the other Asian rhino species. As an inhabitant of the tropical rainforest, the Java rhinoceros prefers soft plant food, but it continues to live mainly solitary. A dedicated conservation program is intended to help save the Java rhinoceros from extinction.

features

The Java rhinoceros is slightly smaller than an Indian rhinoceros and reaches a head-torso length of 3.0 to 3.4 m plus a 50 cm long tail with a shoulder height between 140 and 170 cm. The weight varies between 0.9 and 1.8 t and is more or less comparable to that of the African black rhinoceros ( Diceros bicornis ). The heaviest Java rhinoceros weighed to date weighed 2.3 t. However, the information on weight is generally very uncertain, as only a few specimens could be measured precisely so far. There is no significant difference in size between bulls and cows in this species, but cows may be slightly larger.

The skin is gray to gray-brown and appears black when wet. The skin folds, which resemble those of the Indian rhinoceros, are characteristic. Two larger vertical folds encircle the torso and are located behind the front legs and in front of the rear legs. There are further horizontal folds on the upper limbs . The typical neck folds are smaller than those of its relative, the Indian rhinoceros, but they continue on the back and form a kind of saddle between the neck and shoulder. In the folds there are partly pink pigments . The mosaic-like pattern of pentagonal or hexagonal segments separated by small grooves, with which the entire skin is covered, is very striking. The Java rhinoceros is largely hairless. Hair is only found on the ears, eyelids and the end of the tail. Adult animals sometimes have a small hair fluff on their back as a remnant of the somewhat thicker hair in the youth phase. Also to be emphasized is the pointed upper lip, often drawn far forward, which is very mobile and occurs in all Asian rhinoceros and the black rhinoceros. It is used to tear off the plant food.

The single horn, which is located on the nose, has a predominantly conical shape and is gray-brown in color. Like all rhinoceros horns, this is made of keratin , which gives it a high level of strength and can therefore grow for a lifetime. In contrast to the horn of the Indian rhinoceros, it is much smaller and only becomes 20 cm long. The longest horn ever found measured 27 cm, the length of the horn is influenced, as with all rhino species, by constant rubbing against trees and active use in foraging for food. However, the horns of bulls are longer than those of cows, in which it is sometimes only a small bump or not at all.

The skull of the Java rhinoceros is relatively short and quite wide at 50 to 60 cm. The wide spreading cheekbones give it a wedge-shaped outline. The nasal region is not as long and rounded as that of the Indian rhinoceros. The back of the head is wide and square and leads to a very high posture of the head. In contrast to the African rhinos, the Asiatic ones still have incisors . An adult Javan rhino has the following dental formula . The upper incisors stand vertically in the jaw and are very flat. The lower ones, however, are directed forward. Here the outer incisor is shaped like a dagger and clearly enlarged. Sometimes the first premolars in the upper jaw are reduced. The molars are low to moderately high and have distinct enamel folds .

distribution

Despite its name, the Java rhinoceros did not originally live exclusively on the island of Java . Together with the Sumatran rhinoceros it once inhabited the mainland of Southeast Asia from Bangladesh via Myanmar , Thailand , Laos and Cambodia to Vietnam and was also found on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra . According to new knowledge, it also lived in the south of the Chinese Empire until the 16th century .

Its predominant habitat is dense tropical rainforest in lower elevations. The proximity of water and the presence of mud holes are the prerequisites for the occurrence of the species. The rhinoceros species originally inhabited forests in both low and highlands. In addition to forest areas, other types of vegetation such as mangrove forests in coastal regions or bush landscapes in volcanic mountain regions are tolerated. Overall, however, areas with consistently dense vegetation tend to be avoided, preferring instead, mosaic-like, diverse habitats that also contain open spaces. However, dense forests are needed to seek protection from solar radiation .

Today the Java rhinoceros has been extinguished almost everywhere and has only survived on Java, where it lives in a residual population in the Ujung Kulon National Park on the western tip of the island. Until recently, there was a very small population in mainland Asia in southern Vietnam. WWF experts suspect that fewer than ten specimens of this subspecies lived in a small rainforest north of Saigon , but that this group has since become extinct. The WWF has now announced the extermination of the Java rhinoceros in Vietnam.

Way of life

Territorial behavior

The Java rhinoceros is a nocturnal loner. Bulls and cows only come together for a short time during the mating season , but younger animals sometimes form small groups for a short time. The bulls' territories can be 12 to 20 km² and only overlap marginally. In contrast, the cows' territories are significantly smaller with 3 to 14 km² and overlap at the edges. The areas are marked with urine splashes , also with scratch marks and kinked saplings . Dung is also used as a marker, but unlike other rhinoceros species, the Java rhinoceros does not scratch its feet to distribute the feces on the surrounding bushes. Rather, it carries parts of the waste several meters and distributes it as a visible mark on scratch marks. Furthermore, there are no piled up piles of excrement.

It is unknown whether there will be territorial battles between individuals. If there is a fight, the horn is not used. This is more likely to be used to obtain food. However, the long, sharp incisors of the lower jaw make dangerous weapons that can cause deep wounds. Furthermore, the Java rhinoceros hardly ever uses vocalizations to communicate with conspecifics and is considered to be the "most silent" of all rhino species. Only a snort as a warning and loud whistling, with which it obviously draws attention to its presence, are known. The intra-species communication takes place mainly through the secretions.

Diet

The diet of the Java rhinoceros consists mainly of leaves , fruits , twigs and shoots ( browsing ). The food spectrum includes several hundred different types of plants, 40% of which are more preferred. These include nettles ( Laportea stimulans ), legumes ( Desmodium umbellatum ) and figs ( Ficus septica ). The Java rhinoceros prefer to eat because of the better quality of food available in places that are free of shade, such as in areas with lower vegetation, in small clearings or aisles that have been cut by fallen trees. When eating, the horn is often used to pull plants out.

The Java rhinoceros very often looks for mud holes, which it sometimes deepens with the help of its hooves or horn. These baths are important for thermoregulation and removal of parasites . It is unclear whether this rhinoceros species also affects salt licks, as is the case with the others. In today's distribution area in Ujung Kulon National Park such do not occur. However, the rhinos there occasionally drink sea water.

Reproduction

Little is known about the reproduction of the Java rhinoceros. The gestation period is probably between 16 and 19 months. After that, the cow gives birth to a single calf, but birth has not yet been observed, neither in captivity nor in the wild. The calf is suckled for about a year and stays with the mother for two more years. It is believed that an animal lives around 35 to 40 years old, but the longest zoo was only around 20 years old.

Interaction with other animal species

The Java rhino has no natural enemies. On Java, however, there is a close relationship between the Banteng , the water buffalo and the Java rhinoceros. This can be concluded from the use of the same paths. Sometimes new paths are created, which all three animal species then use. To what extent there is an ecological relationship with the elephant, as with the other rhinoceros species, is unclear, since the Asian elephant became extinct on Java during the Holocene . The original range of the Java rhinoceros was much larger. Attacks on other large animals have occasionally been noted.

Parasites

Numerous parasites can attack the Java rhinoceros. The best known are ticks of the genus Amblyomma . Furthermore, endoparasites such as flatworms (including Anoplocephalidae ), suction worms (including Paramphistomidae ), roundworms and hookworms occur. Recent evidence includes protozoa (including Balantidium and Entamoeba ) that are dangerous to animal health.

Systematics

|

Internal systematics of the recent representatives of the genus Rhinoceros according to Fernando a. a. 2006

|

The Java rhinoceros belongs to the genus Rhinoceros , which also includes the Indian rhinoceros ( Rhinoceros unicornis ). Both species separated in the Middle Miocene , about 11.7 million years ago. The sister taxon is Dicerorhinus with the Sumatran rhinoceros ( Dicerorhinus sumatrensis ). The division into these two genera had already occurred in the late Oligocene 26 million years ago.

There are three recent subspecies of the Java rhinoceros, of which probably only one still exists. Extinct R. s. inermis , the subspecies found in Bangladesh, Assam and Myanmar. The second subspecies, R. s. annamiticus , was long thought to be extinct - in the Vietnam War the defoliant Agent Orange and land mines seemed to have destroyed the subspecies. In the 1990s it was discovered that some specimens of this subspecies had survived in the area of Cat Tien National Park , where an animal was killed by hunters in 1988. The population in the only 40 km² large protected area was estimated to consist of less than ten animals, and their continued survival was considered unlikely. It was noteworthy that the animals were relatively small with 110 to 130 cm shoulder height and a weight of around 800 kg. In addition to the further destruction of habitat by road construction, another specimen was killed in 2010 in the national park by poachers for the illegal trade in horns. Experts now assume that this population has died out. The only subspecies still alive today, R. s. sondaicus was originally widespread on the Malay Peninsula as well as on Java and Sumatra. Today it only occurs in the Ujung Kulon National Park on the western tip of Java Island.

The anatomically described subspecies could at least be used for R. s. sondaicus and R. s. annamiticus can also be confirmed with the help of molecular genetic studies. The samples for this were obtained using remains of skin and hair, heaps of dung and horns. There is therefore a genetic difference between the two subspecies of 0.5% (the difference between Java and Indian rhinoceros is 2.4 to 2.7%), which suggests that the separation into the two subspecies took place a maximum of 2 million years ago . It was also found that R. s. sondaicus occurs with at least three different haplotypes . Haplogroup I and II live from this in the Ujung Kulon National Park, while group III comes from a museum piece with unclear information about its origin. The genetic diversity of the Java rhinoceros is possibly due to its originally highly fragmented habitat, distributed over the Southeast Asian mainland and numerous islands of the Sunda Shelf . The two haplogroups of the Ujung Kulon National Park, which are equivalent in percentage terms, probably go back to a relatively recent repopulation of the area in West Java, which was completely devastated during the Krakatau volcanic eruption in 1883.

Tribal history

The genus Rhinoceros was first recorded for the Pliocene and emerged from the Miocene Gaindatherium or the Punjabitherium or is closely related to these. An early representative was Rhinoceros sivalensis , which is possibly the ancestor of the Indian rhinoceros . The Java rhinoceros, on the other hand, is attributed by some scientists to Rhinoceros fusuiensis from the Old Pleistocene of southern China . The Java rhinoceros can be found for the first time around the same period; in the Pleistocene it lived in some areas at the same time as the Indian rhinoceros and the Chinese rhinoceros ( Rhinoceros sinensis ). At least two fossil subspecies of the Java rhinoceros are associated with R. s. sivasondaicus and R. s. guthi proven. Some teeth from the Sanhe Cave near Chongzuo in the southern Chinese province of Guangxi , which are interpreted as the remains of the Java rhinoceros, belong to the Old Pleistocene . Another early discovery point is one of the Irrawaddy terraces near the village of Pauk in the Magwe Division (Myanmar). Java is an important find area, where the Java rhinoceros has been found in the Middle Pleistocene Kedung-Brubus fauna together with the Indian rhinoceros . The originally wide distribution of the Java rhinoceros is indicated by the fact that it was still to be found on Borneo in the Young Pleistocene. It was only after the end of the last ice age with increasing hunting and poaching that the Java rhinoceros was pushed back to its current refuge on the western tip of Java.

Research history

For a long time the Java rhinoceros, unlike the Indian rhinoceros, which achieved a certain fame with the woodcut by Albrecht Dürer in 1515, was unknown in Europe. A first encounter probably took place in Java in 1630 when the Dutch doctor Jacob de Bondt (1592–1631) was chasing a rhinoceros that had disrupted his party and later found it trapped between several trees. It was not until much later, in 1787, that two rhinos were shot on the same island and brought to the Netherlands, where the Dutch anatomist Petrus Campen studied them. Although he noticed differences to the Indian rhinoceros, he died before his work was completed and published.

In 1822, the French naturalist Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) examined a rhinoceros from Java, which had been hunted there by Pierre-Médard Diard (1794-1863) and which he had sent to Paris. However, Cuvier was only able to publish his report later. It was reserved for the French zoologist Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest (1784–1838) to describe the Java rhinoceros as Rhinoceros sondaicus for the first time in the same year . The animal he used to describe was shot by the naturalist Alfred Duvaucel (1793-1824) on Sumatra.

Several scientific names have been used for the Java rhinoceros over time:

- Rhinoceros sondaicus Desmarest, 1822.

- Rhinoceros javanicus Geoffroy-St. Hilaire & F. Cuvier. 1824.

- Rhinoceros camperis Griffith, (1826?) 1827.

- Rhinoceros javanus Cuvier, 1829.

- Rhinoceros camperii Jardine, 1836.

- Rhinoceros inermis Lesson, 1838.

- Rhinoceros floweri Gray, 1868.

- Rhinoceros nasalis Gray, 1868.

- Rhinoceros frontalis von Martens, 1876 (Lapsus for R. nasalis)

- Rhinoceros annamiticus Heude, 1892.

Threat and protection

The main reason for the acute endangerment of the Java rhinoceros is the demand from East Asia for horns, which according to popular belief there are supposed to have a healing effect in traditional Chinese medicine in a crushed state . Other important reasons are the destruction of the habitat by extensive agriculture and the expansion of human settlements.

Originally the Java rhinoceros lived in many local populations. For the 18th and 19th centuries, numerous hunts and killings of innumerable individuals, especially by the colonial powers of the time, have been attested and documented in what is now the former Dutch East Indies . This was supported by the government of the time, which financially rewarded every animal shot in order to make space for agriculture. The Krakatau eruption in 1883 may also have had an impact on the then dwindling populations. It was not until 1910 that the Java rhinoceros was placed under protection, which, however, only slightly curbed the now illegal killing. On the extreme western tip of Java, the Ujung Kulon National Park was established in 1921 to further protect the Java rhinoceros. The last animal outside the protected area was killed in 1934. Until the early 2000s, only a small group of around 40 animals survived, including only four or five cows of childbearing age. The exact number of animals was unknown.

To protect the remaining Java rhinos from poaching and in addition to study purposes, camera traps were set up in the Ujung Kulon National Park by the WWF and other organizations to record the rhinos and thus give them the opportunity to observe them. The system goes back to the early 1990s. This observation system, which initially comprised around three dozen cameras at strategically important locations for the Java rhino, runs around the clock. With the help of these camera traps, it was possible for the first time in 2010 in the national park to film two cows, each with a young calf, for 30 days. The number of remaining individuals was estimated at 29 to 47, so experts assumed that there would be around 35 to 44 rhinos remaining in the Ujung Kulon National Park in 2011. Investigations In 2014 with a total of more than 140 camera traps, there were at least 58 identifiable rhinos, possibly even 61, which suggests that the population size had increased slightly in the past. By 2019 the number had increased to 63 to 67 animals. The aim now is to stabilize and rebuild this last surviving group, which is highly prone to natural disasters and disease. To this end, the Javan Rhino Study and Conservation Area began to be set up within the Ujung Kulon National Park in 2011 . The 4,000 hectare area is located near the Gunung Hoinje ridge to the east of the national park and has been surrounded by electric fences . Additional water points and salt licks were also set up. The plan is to resettle a group of Java rhinos, to observe and examine them in a targeted manner and to relocate them to a new protected area in the longer term in order to establish a new population that increases the survival chance for the species.

There are currently no Java rhinos in captivity anywhere in the world . The last animal died in Adelaide Zoo ( Australia ) in 1907 and was designated as an Indian rhinoceros during its lifetime. Therefore, the population on Java represents the world's maximum population. In 1965 the Java rhinoceros was filmed for the first time. Helmut Barth and Eugen Schuhmacher made camera recordings of a mother rhino with her young in the Ujung Kulon National Park for their film The Last Paradises .

In October 2011, the International Rhinoceros Foundation and WWF officially declared the Vietnamese subspecies Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus to be extinct after the last known specimen was found dead in Cat Tien National Park in April 2010 . The Myanmar subspecies, Rhinoceros sondaicus inermis , is also considered extinct. The last remaining copies are now only available on Java. The IUCN counts the Java rhinoceros as one of the hundred most critically endangered species due to these circumstances.

literature

- Colin P. Groves and David M. Leslie: Rhinoceros sondaicus (Perissodactyla: Rhinocerotidae). In: Mammalian Species. 43 (887), 2011, pp. 190-208.

- Andries Hoogerwerf: Udjung Kulon: The Land of the Last Javan Rhinoceros. With Local and General Data on the most Important Faunal Species and their Preservation in Indonesia. EJ Brill, Leiden 1970, ISBN 90-04-00963-9 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d H. JV Sody: The Javanese rhinoceros - historical and biological. In: Journal of Mammals. 24, 1959, pp. 109-240.

- ↑ a b c d e Nico van Strien: Javan rhinoceros. In: R. Fulconis: Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6. Info Pack, London, 2005, pp. 75-79.

- ↑ a b Colin P. Groves: The Rhinos - Tribal History and Kinship. In: Anonymous (ed.): The rhinos: Encounter with primeval colossi. Fürth, 1997, pp. 14-32.

- ↑ Colin P. Groves: Species characters in rhinoceros horns. In: Journal of Mammals. 36 (4), 1971, pp. 238-252 (248f).

- ↑ a b Adhi Rachmat Sudrajat Hariyadi, Ridwan Setiawan, Daryan, Asep Yayus3, Hendra Purnama: Preliminary behavior observations of the Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus) based on video trap surveys in Ujung Kulon National Park. In: Pachyderm. 47, 2010, pp. 93-99. ( online ).

- ^ A b Colin P. Groves and David M. Leslie: Rhinoceros sondaicus (Perissodactyla: Rhinocerotidae). In: Mammalian Species. 43 (887), 2011, pp. 190-208.

- ↑ Friedrich E. Zeuner: The relationships between skull shape and way of life in recent and fossil rhinos. In: Reports of the Natural Research Society in Freiburg. 34, 1934, pp. 21-80.

- ↑ a b c R. Schenkel and L. Schenkel-Hulliger: The Javan rhinoceros (Rh. Sondaicus Desm.) In Udjung Kulon Nature Reserve: its ecology and behavior: Field study 1967 and 1968. In: Acta Tropica. 26 (2), 1969, pp. 97-13.

- ↑ a b Mark Szotek: Down to 50, conservationists fight to save Javan Rhino from extinction. In: The Rhino Print. 9 (winter), 2011, pp. 12-14. ( PDF ).

- ↑ a b Kees Rookmaaker u. a .: New literature in the Rhino Resource Center. In: Electronic Newsletter of the Rhino Resource Center. 24 (August), 2011, pp. 1-15. ( PDF ).

- ↑ WWF: Black Day for Species Protection. Rhinoceros extinct in Vietnam. ( online ).

- ^ Sarah Brooks, Peter van Coeverden de Groot, Simon Mahood and Barney Long: Extinction of the Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus) from Vietnam. WWF Report VN, 2011, pp. 1–45 ( PDF ).

- ↑ a b c d Rudolf Schenkel and Ernst M. Lang: The behavior of the rhinos. Handbuch für Zoologie 8 (46), 1969, pp. 1-56.

- ↑ H. Pratiknyo: The diet of the Javan rhino. In: Voice of Nature. 93, 1991, pp. 12-13.

- ↑ a b Adhi Rachmat Sudrajat Hariyadi, A. Santoso, R. Setiawan and A. Priambudi: Automatic camera survey for monitoring reproductive pattern and behavior of Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus) in Ujung Kulon National Park, Indonesia. Proceedings of Asian Zoo and Wildlife Medicine Convention, Bogor Indonesia August 19th – 22nd 2008, pp. 1–2.

- ^ GD Van den Bergh, J. De Vos, F. Aziz, MJ Morwood: Elephantoidea in the Indonesian region: new Stegodon findings from Flores. The World of Elephants - International Congress, Rome. ( PDF ).

- ↑ R. Tiuria, A. Primawidyawan, J. Pangihuatan, J. Warsito, Adhi Rachmat Sudrajat Hariyadi, SU Handayani and BP Identification of endoparasites from faeces of Javan rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus) in Ujung Kulon National Park, Indonesia. Proceedings of Asian Zoo and Wildlife Medicine Convention Chulalongkam University, Bangkok, Thailand, October 26-29, 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ James R. Palmieri and Purnomo and Hartmann Ammaun: Parasites of the Lesser One-Horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus Desmerest). In: Journal of Parasitology. 66 (6), 1980, p. 1031.

- ↑ a b c Prithiviraj Fernando, Gert Polet, Nazir Foead, Linda S. Ng, Jennifer Pastorini and Don J. Melnick: Genetic diversity, phylogeny and conservation of the Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus). In: Conservation Genetics. 7, 2006, pp. 439-448.

- ↑ Christelle Tougard, Thomas Delefosse, Catherine Hänni and Claudine Montgelard: Phylogenetic Relationships of the Five Extant Rhinoceros Species (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla) Based on Mitochondrial Cytochrome b and 12S rRNA Genes. In: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 19, 2001, pp. 34-44.

- ^ Colin P. Groves: Why The Cat Loc (Vietnam) Rhinos Are Javan. In: Asian Rhinos. 2, 1995, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Charles Santiapillai: Javan rhinoceros in Vietnam. In: Pachyderm. 15, 1992, pp. 25-27.

- ↑ Gert Poleti, Tran Van Mui, Nguyen Xuan Dang, Bui Huu Manh and Mike Ba1tzer: The Javan Rhinos, Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus, of Cat Tien National Park, Vietnam: Current status and management implications. In: Pachyderm. 27, 1999, pp. 34-48.

- ↑ WWF: Dead Java rhinoceros in Vietnam. May 10, 2010 ( online ), accessed December 24, 2010.

- ↑ Yan Yaling, Wang Yuan, Jin Changzhu and Jim I. Mead: New remains of Rhinoceros (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla, Mammalia) associated with Gigantopithecus blacki from the Early Pleistocene Yanliang Cave, Fusui, South China. In: Quaternary International. 354, 2014, pp. 110–121, doi: 10.1016 / j.quaint.2014.01.004 .

- ^ Donald R. Prothero, Claude Guérin and Earl Manning: The history of Rhinocerotoidea. In: Donald R. Prothero and RM Schoch (Eds.): The evolution of the Perissodactyls. New-York, 1989, pp. 321-340.

- ↑ Esperanza Cerdeño: Diversity and evolutionary trends of the the family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla). In: Palaeo. 141, 1998, pp. 13-34.

- ↑ Yan Yaling, Zhang Yang, Jin Changzhu, Zhang Yingqi and Wang Yuan: The first fossil record of Rhinoceros sondaicus from the Pleistocene of China. In: Geological Review. 66 (1), 2020, pp. 198–206, doi: 10.16509 / j.georeview.2020.01.014 .

- ↑ Zin-Maung-Maung-Thein, Thaung-Htike, Takehisa Tsubamoto, Masanaru Takai, Naoko Egi and Maung-Maung: Early Pleistocene Javan rhinoceros from the Irrawaddy Formation, Myanmar. In: Asian Paleoprirnatology. 4, 2006, pp. 197-204.

- ↑ Gert D. van den Bergh, John de Vos, Paul Y. Sondaar and Fachroel Aziz: Pleistocene zoogeographic evolution of Java (Indonesia) and glacio-eustatic sea level fluctuations: A background for the presence of Homo. In: Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association Bulletin 14 (Chiang Mai Papers. 1, 1996, pp. 7-21.

- ^ Earl of Cranbrook and Philip J. Piper: Short communicatio: The Javan Rhinoceros Rhinoceros sondaicus in Borneo. In: The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 55 (1), 2007, pp. 217-220.

- ↑ LC Rookmaaker and PW Visser: Petrus Camper's study of the Javan Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus) and its influence on Georges Cuvier. In: Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde. 52 (2), 1982, pp. 121-136.

- ↑ Kees Rookmaaker: First sightings of Asian rhinos. In: R. Fulconis: Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6. Info Pack, London, 2005, p. 52.

- ^ LC Rookmaaker: The type locality of the Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus Desmarest, 1822). In: Journal of Mammals. 47 (6), 1982, pp. 381-382.

- ↑ RhinoResourceCenter ( Javan Rhino Scientific names ( Memento of May 17, 2008 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ Widodo Sukohati Ramono, Charles Santiapillai and Kathy MacKinnon: Conservation and management of Javan Rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus) in Indonesia. In: OA Ryder (Ed.): Rhinoceros biology and conservation: Proceedings of an international conference, San Diego, USA Zoological Society 1993, San Diego, pp. 265-273.

- ^ Nico J. van Strien and Kees Rookmaaker: The impact of the Krakatoa eruption in 1883 on the population of Rhinoceros sondaicus in Ujung Kulon, with details of rhino observations from 1857 to 1949. In: Journal of Threatened Taxa. 2 (1), 2010, pp. 633-638.

- ↑ WWF: Vietnam's last rhinos should give way to the road. May 26, 2009 ( online ), accessed February 24, 2010.

- ^ International Rhino Foundation: Annual report. White Oak, IRF, 2010, pp. 1–21 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Will Knight: Camera traps snap rare rhino calves. New Scientist October 2001, p. 1.

- ↑ WWF Indonesia: Video Camera Update - Ujung Kulon National Park. In: The Rhino Print. (Newsletter of the Asian Rhino Project) 3, 2009, p. 8.

- ↑ Adhi Rachmat Sudrajat Hariyadi: Video trap monitoring the birth of Javan rhinoceros in Ujung Kulon National Park. In: The Rhino Print. 8 (Summer), 2011, pp. 12-13.

- ↑ Adhi Rachmat Sudrajat Hariyadi, Agus Priambudi, Ridwan Setiawan, Daryan Daryan, Asep Yayus and Hendra Purnama: Estimating the population structure of Javan rhinos (Rhinoceros sondaicus) in Ujung Kulon National Park using the markrecapture method based on video and camera trap identification. In: Pachyderm. 49, 2011, pp. 90-99 ( online ).

- ^ International Rhino Foundation: Some Bright Spots for Javan Rhinos. 2014 ( online ).

- ^ A b International Rhino Foundation: State of the Rhinos. ( online ).

- ↑ Bibhab Kumar Talukdar: Asian Rhino Specialist Group report. In: Pachyderm. 49, 2011, pp. 16-19 ( online ).

- ^ Susie Ellis and Maggi Moore: Conserving the Javan rhinos. In: International Zoo News. 58 (6), 2011, pp. 403-405.

- ↑ Inadequate protection causes Javan rhino extinction in Vietnam [1] .

- ↑ IUCN information sheet on the 100 most critically endangered species, engl.

Web links

- Profile of the Java rhinoceros with a ZDF video

- Sensation: Java rhinoceros in the camera trap ( with calf ) , video from WWF on YouTube , published on September 22, 2015

- ARKive information and images (in English)

- Rhinoceros sondaicus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: Asian Rhino Specialist Group, 1996. Accessed on 24 February, 2009.