José Rizal

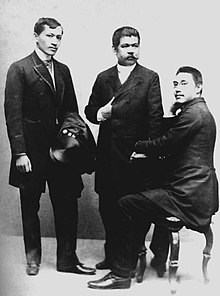

José Protacio Mercado Rizal y Alonso Realonda (born June 19, 1861 in Calamba City on Luzon , † December 30, 1896 in Manila ) was a Filipino writer , doctor and critic of colonialism . In the Philippines he is revered as a national hero ( pambansang bayani ) and his memory is officially celebrated on December 30th ( Rizal Day ), the anniversary of his execution by the Spanish colonial regime.

He was a reformer who wanted to give the Philippines - at least for a transitional period - the status of a largely independent Spanish overseas province. He owes his fame in the Southeast Asian world not only to his novels, but also to his non-violent resistance against the arbitrary rule of the Spanish colonial power, which has been proclaimed in numerous essays.

Origin and youth

Rizal was the seventh of eleven children of the married couple Francisco Rizal Mercado and Teodora Alonso and was born in Calamba City in the province of Laguna . Rizal came from a multi-ethnic family. Its founder was a Chinese from Fujian named Domingo Lam-co, who immigrated to the Philippines at the end of the 17th century, married an Inés de la Rosa and opened a business. Due to a decree of the Governor General, Lam-co had to choose a Spanish surname and chose “Mercado”, which meant “market” and referred to his professional activity. Rizal's mother Teodora was the daughter of the granddaughter Lam-cos (Brígida de Quintos) and a Filipino delegate to the Spanish Cortes (Lorenzo Alberto Alonso).

José Rizal kept the family name Mercado until he attended school in Manila. When his brother Paciano, who was ten years his senior, was targeted by the Spanish prosecuting authorities because of his connections to the Filipino priest José Burgos, who was executed for alleged incitement to riot , he recommended the younger brother to choose "Rizal" (green rice stalk) as his family name in order to avoid attracting attention to attract the authorities.

Studies and stays abroad

Rizal traveled to Manila in 1872 to attend the Ateneo Municipal de Manila high school, which he graduated with a bachelor's degree in 1877, supported by Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista . During his school days he took part in literary competitions, wrote poems, short sketches and prose pieces and received several awards. He continued his education at the Ateneo, and at the same time enrolled at the University of Santo Tomás for the subjects of literature and philosophy. When he learned that his mother was blind, he decided to study medicine, but interrupted his studies to leave for Europe in 1882 . He finished his medical studies at the Universidad Central de Madrid in 1884 and a year later a second degree at the Philosophical Faculty of the same university. Rizal was admitted to the Freemasons ' Union in 1884 , his lodge was the Acacia Lodge No. 9 in Madrid . After graduating, he specialized in the Paris eye clinic of the then famous ophthalmologist Louis de Wecker and went from there to Heidelberg , where he continued his specialist training in 1886 at the university eye clinic of the ophthalmologist Otto Becker . In Wilhelmsfeld near Heidelberg he lived for a few weeks with the family of Pastor Karl Ullmer, who encouraged him to translate Schiller's freedom drama Wilhelm Tell into his mother tongue - the Tagalog . A memorial was later erected for Rizal in Wilhelmsfeld, while Heidelberg commemorates his stay with various commemorative signs and a street name.

From Spain, Rizal made numerous trips to Germany , Belgium , England , France , Italy , Switzerland , Austria-Hungary , and later to Japan and through the USA . He was friends with one of the best experts in the Philippines, Ferdinand Blumentritt in Litoměřice , Bohemia , where a memorial commemorates his visit. During an extended stay in London he worked in the library of the British Museum and was particularly supported by his host , Reinhold Rost , the chief librarian of the India Office Library , who was used the Spanish royal family for his Filipino friend. In 1887 Rizal became a member of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory . When he returned to the Philippines in 1892, he and his colleagues there founded a reformist secret society called La Liga Filipina .

Works and Heritage

Rizal's books, especially his most famous work Noli me tangere (Don't touch me), which was printed and published in Berlin in 1887, criticized the arbitrariness of the colonial regime and the illegal abuse of power by Spanish priests and monks. In Noli me tángere , corruption, land grabbing and the sexual abuse of native women by Spanish monks are portrayed or hinted at. His second and more dramatic work El Filibusterismo ( The Rebellion ), which builds on the first and was printed in Ghent (Belgium) in 1891 , is about the preparation for a violent coup and its failure, but also about the everyday repression by the Guardia Civil and last but not least, the unconsequential rebellion of the students against the teaching pedagogy common in clerical schools and universities. The education and knowledge of the locals were considered a danger to the monastic orders, which monopolized the educational system. Rizal's works were indexed as soon as they were published and their possession made a criminal offense. In the attribution of his novel El Filibusterismo , Rizal had also erected a literary memorial to the members of the innocently executed GOMBURZA group , which his opponents accused him of as an indirect call for revolution.

During his stay in London (1888) Rizal devoted himself to the critical commentary on the Philippine Chronicle Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas (History of the Philippine Islands) by the Spanish lawyer Antonio de Morga , published in 1609 . The annotated edition was published with a foreword by Ferdinand Blumentritt in 1890 by the Paris publisher Librería de Garnier Hermanos.

Rizal was a leading member of the propaganda movement of Filipino students in Europe and wrote political articles for their newspaper La Solidaridad . Among other things, he called for the Philippines to become a Spanish province, a Filipino representation in the Spanish parliament ( Cortes ), the replacement of Spanish priests in the Philippines by locals, freedom of speech and assembly, and equality before the law for all residents of the archipelago. In 1892 Rizal returned to the Philippines from Europe and founded the reformist Liga Filipina , which was immediately banned by the Spanish Governor General.

Rizal's novels Noli me tangere and El Filibusterismo were translated into numerous languages and, in the early 1950s, made mandatory reading in all schools and universities in the Philippines.

Sentencing and execution

Because of his political novels, his criticism of the arbitrariness of the Spanish colonial rulers published in numerous essays and because of his reform plans aimed at equitable distribution of land and parliamentary representation, Rizal was exiled by the Spanish executive powers for four years to Dapitan in the province of Zamboanga del Norte (on Mindanao ) sent. There Rizal built a school and a hospital, constructed a water supply system for the farmers and worked as an ophthalmologist, while the supervising authority allowed him to continue his scientific correspondence with his European friends. In the summer of 1896, the regime even allowed him to move to the island of Cuba, where he was supposed to work as a military doctor in the Spanish service. While he was waiting for the passage of the ship in the port of Manila, guarded by the military, the Katipunan secret society started the first actions of the Philippine Revolution in Cavite province . Although Rizal arrived in Barcelona by ship, he was brought back to Manila by return mail in a troop transport and brought before a court martial. The Spanish colonial rulers wanted to set an example and condemned him, who expressly refused to use force, for inciting rebellion to death by shooting. On December 29, 1896 - the evening before his execution - he wrote in a letter dedicated to his long-time friend Ferdinand Blumentritt: My dear brother: When you have received this letter, I will be dead. Tomorrow at 7:00 am I will be shot, but I am innocent of the crime of rebellion. I am dying with peace of mind.

On December 30, 1896, Rizal was executed at the gates of Manila (now called Rizal Park ) in Manila. On the day before his death, he had crossed out the ethnic designation “mestizo chino” (Chinese hybrid) on the confirmation of his death sentence and replaced it with “indio” (local), thus declaring himself to the people. The night before his execution he also wrote the poem “Mi último adiós” (My last farewell), which he secretly gave to his sister. The poem became an inspiration to the Filipino revolutionaries of the time, but was also recited decades later by Indonesian revolutionaries before decisive battles.

Monuments

In Rizal Park , Manila, there is a large memorial at the place where he was shot, created by the Swiss Richard Kissling , with the inscription: “ I want to show to those who deprive people the right to love of country, that we indeed know how to sacrifice ourselves for our duties and convictions; death does not matter if one dies for those one loves - for his country and for others dear to him. "(To all those who deny the people the right to love their homeland, I want to prove that we are very much ready to die for our duties and convictions. What does death mean if you die for those you love - for his country and for those who are dear to you.)

In 1972 the Philippines minted a 1 piso coin in memory of Rizal .

Furthermore, in Manila , in the Intramuros district , there is the fortress Fuerza de Santiago from Spanish colonial times, in which Rizal was imprisoned before his execution. The fortress now houses a museum in which, among other things, exhibits by and about Rizal can be seen, for example the text of the poem "Mi último adiós" in several languages, including German, and a shrine (Rizal Shrine) in honor of Rizal. The dungeon is also still there and can be visited. The Jose Rizal Memorial Protected Landscape was established in Dapitan City on April 23, 2000 ; it shows, inter alia. Replicas of the buildings designed by Rizal at the time.

December 30th is a national holiday in the Philippines in honor of Rizal.

Two universities bear the name of José Rizal, the José Rizal University in Mandaluyong City and the José Rizal Memorial State University in Dapitan City.

The German School Manila also bore his name for a long time.

A statue of Rizal and the bronze portraits of his contemporaries are in the Rizal Park, inaugurated in 1978 in Wilhelmsfeld , Baden-Wuerttemberg . A section of the banks of the Neckar in Heidelberg is named after Rizal. In 2014 a memorial stone was unveiled there.

reception

- 2016: Hele Sa Hiwagang Hapis (film)

Fonts

- Noli me tángere . Novela Tagala. Berlin: Berliner Buchdruckerei-Actien-Gesellschaft, 1887.

- Noli me tangere. Novel. From the Filipino Spanish by Annemarie del Cueto-Mörth, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 1987, ISBN 3-458-14585-0 .

- El Filibusterismo . Novela Filipina. Ghent: Boekdrukkerij F. Meyer-van Loo, 1891.

- The rebellion. Novel. Translated from the Filipino Spanish by Gerhard Walter Frey. MORIO Verlag, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-945424-29-2 . (Original title "El Filibusterismo")

- Sucesos de las islas Filipinas por el Doctor Antonio de Morga, obra publicada en Méjico el año de 1609, nuevamente sacada á luz y anotada por José Rizal y precedida de un prólogo del Prof. Fernando Blumentritt. Paris: Librería de Garnier Hermanos, 1890.

- Epistolario Rizalino , 5 vols. Manila: Documentos de la Biblioteca Nacional de Filipinas, 1930 - 1938.

- Escritos políticos e historícos por José Rizal , Vol. VII. Manila: Comisión Nacional del Centenario de José Rizal, 1961. Political and Historical Writings. Manila: National Historical Institute, 2000.

literature

- Bernhard Dahm : José Rizal, the national hero of the Filipinos. (= Personality and history. Volume 134). Muster-Schmidt, Göttingen / Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-7881-0134-2 .

- Donko, Wilhelm: Austria-Philippines 1521–1898 - Austrian-Filipino points of reference, relationships and encounters during the period of Spanish rule. Publisher epubli.de, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-8442-0853-5 . (On the subject of J. Rizal and his friendship with Ferdinand Blumentritt, pp. 243–292)

- Gerhard Frey: Violence or non-violence in conflict resolution: alternatives in Friedrich Schiller and José Rizal. In: Heidelberger Jahrbücher 48 (2004), pp. 333–346. ISBN 3-540-27078-7 .

- Dietrich Harth : José Rizal's struggle for life and death. Facets of a biography critical of colonialism. Heidelberg: heiBOOKS 2021, 523 pp. ISBN 978-3-948083-34-2 .

- Annette Hug : Wilhelm Tell in Manila. Roman, Heidelberg: Verlag Das Wunderhorn, 1st edition. March 17, 2016, 192 pages, ISBN 978-3884235188 .

- Kluxen, Guido: José Rizal (1861-1896), ophthalmologist and national hero of the Philippines. In: Frank Krogmann (ed.): Communications from the Julius Hirschberg Society for the History of Ophthalmology 16 (2014 [published 2018]), pp. 273-289

Web links

- Literature by and about José Rizal in the catalog of the German National Library

- Work and life

- Mi Ultimo Adiós (German)

- Works by José Rizal (Spanish, Tagalog, English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Vicente F. del Carmen: Rizal. An Encyclopedic Collection . tape 1 . Quezon City 1982, p. 3 ff .

- ↑ srjarchives.tripod.com

- ↑ Dietrich Harth: José Rizal's struggle for life and death . Heidelberg 2021, ISBN 978-3-948083-35-9 , pp. 226-241 .

- ↑ Harth 2021, pp. 109-145

- ^ O. Weise: The orientalist Dr. Reinhold Rost. His life and striving (communications from the Eisenberg History and Antiquity Research Association, 12th issue). Leipzig 1897, p. 49; 65.

- ↑ La Liga Filipina

- ↑ Harth 2021, pp. 226–241

- ↑ Harth 2021, pp. 469–472

- ^ Escritos de José Rizal tomo 11. Correspondencia epistolar entre Rizal y el profesor Fernando Blumentritt 1. Manila 1961, p. 920.

- ↑ heidelberg.de - July 14, 2014 memorial stone inaugurated on the Rizal-Ufer. Retrieved January 16, 2021 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rizal, José |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Rizal Mercado y Alonzo Realonda, José Protasio (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Filipino writer, doctor and national hero |

| BIRTH DATE | June 19, 1861 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Calamba City , Luzon |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 30, 1896 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Manila |