Cliff (coin)

Cliff is a name for angular coins or medals . Cliffs were made from a variety of metals and were often used as siege and emergency coins . Since the 17th century, silver or gold commemorative coins were often minted as cliffs; today they play a major role in the collectible coin market .

etymology

In Scandinavia, the square coins first produced there around 1460 under King Christian I of Denmark, Norway and Sweden are known as clipping . The word refers to the then common method of making coins and is derived from the Swedish klippa ("cut", "scissors", "snap off"). The term later came into international use in numismatics , so cliffs are also called klippe in English .

history

Square coins (square, triangular, polygonal or irregularly shaped) are already known in great variety from ancient times . They were made independently in several cultures; sometimes as the sole form for a long period of time, in other cases together with round coins. The production under difficult conditions such as time pressure and a lack of tools or personnel meant that emergency coins and siege coins were often made as cliffs in Europe, which was shaken by armed conflicts in the 16th and 17th centuries. A particularly large number of cliffs have survived from these two centuries. It is noteworthy that despite the adverse circumstances, such as a current threat from enemy troops, the coins were almost always made from the precious metals common in coinage at the time. If necessary, courtly silver dishes were cut up for this purpose - as was the case in 1610 during the siege of Jülich . There are, however, early examples of making siege coins from base metals such as tin or lead, and in the 20th century iron or zinc was often used for emergency coins.

The technique of minting coins can be easily reconstructed by examining the archaeological finds for the material composition and for traces of processing for ancient coins. The Roman historian and writer Gaius Plinius Secundus left details on metalworking in antiquity in books 33 and 34 of his Naturalis historia around AD 77. Other ancient authors commented on coin weights and the types of precious metals to be used. It was only since the Middle Ages that there have been significant written records about the production of coins themselves.

Minting coins was still a craft in Europe during the early modern period. Until the first mechanization of the work processes, the coin metal was cast in pieces, the Zaine . These were first leveled in the coin by the custodian and struck to the dimensions and thickness intended for the coins. Then, the shot master cut the planchets with the Benehmschere from the metal, which are leveled by the process again with hammer blows needed. Alternatively, the planes were punched out of the zain that had been cut to the correct thickness using a suitable tool. Finally the master setter received the prepared flans and stamped them on them. The cutting of the teeth or plates into square, rectangular or diamond-shaped planes could be done more quickly and thus left less residue to be remelted. Such a development from round to square coins, to make work easier, is assumed to be the impetus for the extensive minting of cliffs in Salzburg in the 16th and 17th centuries.

In the case of the roller minting mechanisms introduced into coinage in the middle of the 16th century , the Zaine could be put into the machine as such. Here, the material was brought to the exact desired thickness with two counter-rotating rollers and several coin images were pressed in at the same time (four to six large and / or up to 19 small images). The finished coins only had to be ejected from the processed zain. The pocket work introduced in the 17th century only had two dies - for the front and back of the coins - which simultaneously stamped a series of coin images between the zaines in one work step.

A disadvantage of these minting machines was that the dies for circular coins had to have an oval shape because the rotating rollers applied the image to the teeth in a distorted manner. Their advantage with regard to the production of cliffs was that, apart from the production of the dies , any desired shape of the coins could be produced with a similar effort. However, the blanks were not only deformed with regard to the undesired distortion of the image side, but also bent as they passed through the rollers. As a result, the coins produced could no longer be stacked properly. Since this deficiency could not be remedied by adapting the die, the roll embossing machines were soon abandoned and machines were introduced in which the coins could be struck with a punch that hit it vertically. The next new tool in coin production, the clip mechanism , could only be used for small coins. This solved the problem of the deformation of the planets. The general introduction of spindle mechanisms at the end of the 17th century ultimately made the shape and size of the coins insignificant. With regard to everyday coins, it turned out that the production of cliffs no longer offered enough advantages over round coins to outweigh the practical disadvantages of using the coins.

But since the 16th century, cliffs came into circulation more often as coins on special occasions. In contrast to the first cliffs with small denominations such as the Swedish Fyrk , which were intended for circulation , they were often coins made of silver or gold with high denominations. Examples of such cliffs are the Salzburg cliffs to commemorate the suppression of the revolt of the Salzburg citizens against their archbishop in 1523. Likewise numerous editions to celebrate the Peace of Westphalia (Free Imperial Cities of Münster and Nuremberg); also of anniversaries of the Reformation ( Free Imperial City of Nuremberg ) or of births, baptisms, days of death and state visits (Electorate of Saxony).

Beyond the coinage, cliffs were often chosen as the shape of shooting and school rewards in the 17th and 18th centuries. The corresponding pieces form the own genre of the shooting cliffs in numismatics . These medals could have their origin in the silver cliffs minted in 1678 in the Electorate of Saxony for the opening of the Dresden Schützenhaus. In Saxony, even more silver cliffs were issued on the occasion of shooting competitions in the following decades. In addition, gold and silver cliffs were still minted in many states, often as commemorative coins with high face values, which also stood out due to their design, which deviated from the usual coins.

From the beginning of the 18th century, economic motives for the manufacture of cliffs were decisive in several cases. The lack of silver and gold and the need to process copper, which was available in large quantities, in the Kingdom of Sweden and the Russian Empire led to the production of copper coins in considerable dimensions, which were nevertheless legal tender.

The role of the cliff as a war and occupation coin extended well into the 20th century. In 1915, under German occupation during the First World War, square brass cliffs were issued in the Belgian city of Ghent ; later coins for the same occasion were round. During the Second World War , the square coins of the German occupying power in the Netherlands were made from zinc. Cliffs intended for normal money transactions are not common in recent times, but they still exist; for example in the Netherlands Antilles and in Chile. These are often currency coins with the smallest face value of a country, made from an inexpensive alloy, and in a different shape to avoid confusion.

In most cases, the cliffs minted today are commemorative coins . The choice of the unusual shape is made with a view to the collector's market. Cliffs still have a proportionately greater importance in the case of medals ; here the unusual shape appears attractive. However, one of the original motivation for producing angular coins, the simplification of coin production, no longer exists. With modern tools, using other than round flutes can be problematic.

Examples

Ancient: Greek, Roman and Indian cliffs

Ancient Greece

The founding of the Greek coinage is the Lydians of the seventh century BC. Attributed to BC, from there coins spread first to Ionia and further over the entire Greek sphere of influence. The round shape was preferred and the cliffs, handed down in great variety from the Greek-Bactrian Kingdom and the Indo-Greek Kingdom, are a specialty. They come from the easternmost region of the Greek sphere of influence, which extended into what is now Afghanistan and India, and from the last two centuries before Greece was integrated into the Roman Empire. These coins took their shape from Indian coins, and in contrast to the round coins of the homeland, the flans were not cast, but rather cut out of metal plates in squares. The shape of the coins represents one of the adaptations of the Greeks to the culture of the conquered areas, as evidenced by coins.

The silver drachm shown with a weight of around 2.4 g and an edge length of 15 mm is of particular interest because of its bilingual inscriptions. On one side it bears a picture of an elephant with a rope around its belly, to which bells are attached, and a Greek inscription. The other side shows a zebu and a lettering in Kharoshthi . This bilingual design of the coins was retained by the rulers of Bactria for almost a century. The coins differ in the animals or symbols shown and can be assigned to a ruler with the help of the wording of the inscriptions. In many cases the reign of a Bactrian ruler, or even his existence, can only be proven with the help of coin finds. The bilingualism of the inscriptions was not limited to the Indo-Greek Kingdom. Coins minted in Judea with Greek inscription on one side and Hebrew inscription on the other side.

Roman Empire

In the early days of the Roman Empire , financial obligations or assets were expressed in “pieces of cattle”, the term pecunia (“money” or “property”) is derived from pecus (“cattle”). The first metal currency were the aera rudi or aera infecti ("raw ore", "unprocessed ore", singular aes rude , aes infectum ), cast bars or irregularly shaped metal chunks of copper or bronze weighing between 2 g and 2.5 kg.

From around 320 BC. BC the metal bars were provided with representations on both sides, even with these aera signati their weight corresponded to the monetary value they embodied. The depicted "Aes signatum" with the trident dates from approx. 260 BC. Chr. And weighs about 1,150 g with a dimension of 8.8 × 18.3 cm. On the back, the piece bears a caduceus with two rings on top. The upper ring is open and is formed by two serpentines facing each other. Like the trident, the Hermes staff is also wrapped in a ribbon with a bow.

The further development of the aes signatum was the aes grave . It was cast like its predecessors, but it was round in shape and for the first time had a face value, expressed as a number or as a number of raised spheres on the surface. Only the aera gravi corresponded in practical terms to today's concept of coin. Although many of these metal bars or early coins are formally regarded as cliffs, the pieces are usually not referred to as cliffs, but rather by numismatists using their Latin names, e.g. B. "Aes signatum" addressed.

India from ancient times to today

On the Indian subcontinent there has been at least since the 5th century BC. BC coins. In the northern Indian region of Malwa , in the vicinity of today's city of Ujjain , square cliffs were created even before our era. The metals used were already diverse at that time, bronze, copper, silver and gold were used.

Until the present day, regardless of the influences of invasions by the Greeks, Arabs, Persians and Europeans, there have been cliffs in many Indian states. In some regions they were the norm and round coins the exception. In Indian coinage, local coinage traditions often developed that retained their preferred shapes and motifs for generations or even centuries, and in individual cases withstood the settlement of a region by another people. The characteristics of the early Indian coins were adopted by the Greek conquerors, namely the representations of Indian deities and the square shape, otherwise unknown in the Greek sphere of influence. After the decline of Greek culture, coins remained square under the rule that followed.

These spatially limited traditions meant that in larger empires, such as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, the empires of the Maurya , Kuschana and Gupta, or the Mughal Empire, numerous different types of coin circulated. Many of the more than 600 Indian princely states had mint sovereignty in their national territory. Cliffs have been shaped in great variety by these principalities. Some states only spent cliffs at all.

The British colonial rulers also adapted to the tradition of square coins, with some issues. Cliffs were circulating in British India until independence from India and Pakistan in 1947. Until shortly before the end of the 20th century, Pakistan minted square cliffs as circulation coins. The same was true for Burma (now Myanmar), which was spun off from British India in 1937, and just a few years ago Indian coins valued at 2 rupees were 11-sided.

Cliffs

The collapse of the great empires - in India the Gupta empire , in Europe the Greek and Roman empires - had a direct impact on the volume of trade and indirectly on coin production. The number and variety of coins decreased significantly here and there. However, cliffs are also known from this period in India as well as from Europe. The usual shape of the coins was round, but there are examples of cliffs from the Byzantine Empire , and pennies were also made as cliffs in Bavaria.

Most of the siege or war cliffs were spent in connection with the wars of the 16th and 17th centuries. During the first Turkish siege of Vienna in 1529, several cliffs were issued; In the Schmalkaldic War there were at least four warring parties who issued emergency cliffs. In the Thirty Years' War with its large troop movements, the largest number of the war cliffs known today arose. The main reason for this was not the material need of the people in the besieged cities and fortresses, but from the Schmalkaldic War and especially during the Thirty Years' War the need to pay the mostly hired mercenaries for their war services. A distinction can be made in that some war cliffs were issued by military commanders, such as 1610 and 1621–1622 in Jülich . Other coins, however, were initiated by the princes, without direct connection with acts of war, in order to rehabilitate the state treasury burdened by a war. The Jülich cliffs from 1543 are an example of this .

Kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden in the 15th and 16th centuries

The first Scandinavian Klippinge appeared in the middle of the 15th century. But it was only in connection with the Swedish War of Liberation between 1519 and 1523 that King Christian II of Denmark, Norway and Sweden as well as his opponent Gustav I. Wasa issued large quantities of Klippinge . The Klippinge Christians came in four denominations, 14 pennings made of silver, 6 pennings made of bad silver, and copper coins of 4 and 3 pennings. Christian II was given the nickname Kong Klipping ("King Klipping") because of the large number of cliffs he published . Subsequent kings also published Klippinge, according to Christian III. of Denmark and Norway from 1534 to 1535. During the Three Crowns War from 1563 to 1570, both Frederick II of Denmark and Norway and Erik XIV of Sweden made klippinge with a metal content below their nominal value.

Prince Archbishopric of Salzburg in the 16th and 17th centuries

The Prince Archbishopric of Salzburg was a state in the Holy Roman Empire from the middle of the 14th century until the secularization of 1803 as the secular domain of the Prince Archbishop of Salzburg . Prince Archbishop Leonhard von Keutschach (r. 1495–1519) led the economically depressed country to an economic boom, which was also due to the gold and silver mining in the country. The coinage was reformed by him, and Salzburg's new prosperity was also reflected in coin production. From 1512 a large number of different coins were minted in Salzburg. When a new prince archbishop took office, the coin series were provided with the portrait of the new ruler. To this end, commemorative coins were issued on numerous occasions; mostly round coins, as well as cliffs.

During an unusually long period of around 200 years in Europe, cliffs were formed in the Prince Archbishopric of Salzburg; predominantly gold and silver cliffs with higher denominations. Some of the coins minted in Salzburg are among the greatest numismatic rarities, some only exist as unique pieces in important museum collections. In 1687, a gold cliff weighing 175 g was minted for 50 ducats, other rarities are specimens, incorrect mintings with the wrong weight (e.g. 1/4 thaler on a blank for 1 thaler), " hermaphrodites ", these are coins in front - and on the reverse bears imprints of stamps from various issues, or coins that should only be minted in a few pieces from the start.

Duchy of Jülich 1543–1622

The Duchy of Jülich was located in the Rhineland, northwest of Cologne, and was of considerable strategic importance because of its location near the Netherlands. In the course of history there were three major sieges of the city, namely 1543, 1610 and 1621–1622. Cliffs were released on the occasion of all three sieges. The Jülich emergency cliffs from 1543 are still war coins that were made without any direct connection to the siege in order to be able to pay the troops their wages. Only the cliffs of 1610 and 1621/1622 were siege coins in the true sense, issued by the respective fortress commanders.

The Jülich emergency cliffs from 1543 are, even more so than the editions from 1610 and 1622, the greatest rarities in numismatics . The originally low edition also contributes to this, as does the fact that most of the cliffs have been melted down and used up as silver.

The siege cliffs of 1610 were partly made of cut silver dishes and had values from one to 20 thalers. There was also a gold coin worth 40 thalers. The coins from 1621 appeared with a face value of 2 stüber up to one thaler, the value levels up to 20 stüber were also issued as cliffs. Unlike the cliffs of 1547 and 1610, they had value stamps in all corners to make it difficult to trim the coins afterwards.

Gotha 1567

After the brothers Johann Friedrich II. Of Saxony , Johann Wilhelm and Johann Friedrich III. Having ruled the duchy of Saxony, inherited from their father, for eleven years, the older brothers agreed in 1565 to partition Saxony. Johann Friedrich II received Coburg and Eisenach, and Johann Wilhelm Weimar. Johann Friedrich II. Moved into his residence in Gotha and continued to demand for himself the Saxon electoral dignity, which his father was forced to give up. He took the friend of his knights and adventurers Wilhelm von Grumbach with him, although this since November 1563 because of breach of the peace under imperial ban had stood, and the Emperor Charles V had forbidden him to take Wilhelm with him. Wilhelm influenced Johann Friedrich and promised him, supported by a fortune teller and court official, that he could regain the electoral dignity without armed conflict. In May 1566 the Reichstag decided to confirm the eight over Wilhelm von Grumbach and to enforce it, on December 12, 1566 Johann Friedrich was ostracized. August of Saxony, commissioned with the execution of the Reich , besieged the city of Gotha and Grimmenstein Castle with almost 10,000 soldiers from December 30, 1566. The siege lasted until the city surrendered on April 11, 1567, and on April 18, Wilhelm von Grumbach and others involved in the disputes later known as Grumbach's Handel were executed on the market square in Gotha. Johann Friedrich II spent the last 29 years of his life in imprisonment .

During the siege of Gotha, emergency cliffs were made of gold and silver in several variants in the city to supply the population . The cliffs show on the front the Saxon coat of arms with course swords, the lettering "H HF GK" for "Duke Hans Friedrich Geborener Kurfürst" and the full or two-digit year 1567. There are similar cliffs that bear the year 1547 and on which instead of “H HF GK” just “H HF K”. However, these are war cliffs of Elector Johann Friedrich I from the Schmalkaldic War . There are also the cliffs from 1567 with an inscription on the back relating to the Duke's capture. It is believed, however, that these inscriptions were subsequently applied to existing coins.

The use of the coat of arms with Kurschwertern and Duke Johann Friedrich II., In contrast to his father, the title of "Born Elector" on the cliffs from 1567, which he is not entitled to, can also be understood as a propaganda measure. In the same year, Elector August von Sachsen responded with a separate edition for the same occasion. He had a commemorative coin struck in Dresden for the capture of Gotha with a demonstratively large Kurschild. The Latin inscription translates as “Finally the good thing wins”, and the inscription on the reverse “When the city of Gotha was conquered in 1567, the punishment of the outlawed besieged enemies of the empire was carried out and the rest were put to flight, August, Duke to Saxony and Elector, make (this coin). "

Breda 1577

During the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648) between the Protestant northern Netherlands and Spain, the rule of Breda changed at least six times; the city was repeatedly under siege. The first siege of Breda took place as early as 1577. On November 4, 1576, mercenaries in the Spanish service who had been unpaid for months plundered the city of Antwerp . The attacks lasted three days, claimed 8,000 to 10,000 lives, mostly civilians, and resulted in the destruction of a third of Antwerp's residential buildings. The sack of Antwerp was later referred to as the Spanish Fury . Only a few days later, on November 8th, 1576, Holland, Zealand and the southern provinces joined forces in the Ghent pacification to drive the Spanish troops off Dutch soil. At the beginning of 1577 the garrison in Breda consisted of 112 men of Spanish light cavalry under the commandant Antonio d'Avila and three companies of German mercenaries in Spanish service under Colonel Freundsperg (often Fronsberg in Dutch texts ). D'Avila left Breda on January 7th, 1577 with 50 cavalrymen, the highest-ranking Spanish officer in the fortress was Lieutenant Juan de Cembrano. In March he and his soldiers left the fortress, which was then under the command of Colonel Freundsperg.

The marauders of Antwerp fled after their deed, pursued by Dutch troops under Count Philipp von Hohenlohe-Neuenstein and the Antwerp city commander Frédéric Perrenot von Champagney. They were expelled one by one from Bergen-op-Zoom, Wouw and Steenbergen and Karl Fugger, one of their leaders, was captured. In the summer of 1577 the mercenaries were under the command of Colonel Freundsperg in Breda. The ring drawn around the city by the Dutch troops under Count Hohenlohe became increasingly narrow, at the same time the Dutch tried to persuade the German troops to leave the city through negotiations and bribery. The Germans received money on August 11 and 15, but the bribe had no effect. On August 22nd, the garrison was reinforced with three German companies from Antwerp. This worsened the already tense financial situation of the Breda citizens, who had to provide for the food, accommodation and pay of the foreign soldiers and who were constantly confronted with excessive financial demands by the Germans.

On August 24th, the citizens of Breda were instructed to bring silver to the town hall for the production of emergency coins. At the same time it was decreed that the silver cliffs made from it were to be accepted as a means of payment . Since this measure was not sufficient, from September 4, 1577 cliffs were made of tin and lead, the acceptance of these coins was ordered. During a few weeks, emergency coins were therefore issued as at least five different types.

After tough negotiations between the troops of Count von Hohenlohe and Colonel Freundsperg, Breda paid the German occupiers a further 3,900 Karlsgulden as wages for ten days on October 3, 1577 , and the troops left Breda the following day. In the period from July 16 to October 4, the city of Breda paid the Germans 31,119 guilders and 8 stüber, far more than the construction of the Breda emergency cliffs had provided. Even after the siege there were costs; a gift made by goldsmiths from the citizens of Breda to the Duchess of Nassau, wife of Wilhelm I, cost 3,000 guilders. A Rittmeister at Wilhelm's court received a collection of emergency cliffs, consisting of 4 silver cliffs for 20 rooms (or one guilder), 8 silver cliffs for 10 rooms, 7 tin cliffs for 3 rooms and 10 made of tin for one room.

Cliffs in peacetime from the 16th to 19th centuries

Free Imperial City of Nuremberg 1578–1717

From 1562 to 1613 silver coins for three cruisers were minted in the Free Imperial City of Nuremberg, with the city coat of arms on the front and the imperial orb in a diamond on the back. These coins were also issued as triangular cliffs in 1578 and 1584.

A square gold cliff of three ducats from 1648 showed the Nuremberg city arms with a Latin text on the front and a lamb standing on an open Bible on the back. The coin commemorated the Peace of Westphalia . On the front it bears a Latin inscription with partly larger embossed letters as a chronogram : "EST VBI DVX IESVS PAX VICTO MARTE GVBERNAT", the sum of the letters that can represent a Roman numeral results in the year 1648.

Another three ducat coin followed in 1650, with the German inscription "Gedächtnis des Friedensvollendungsschluss in Nürnberg 1650" on the obverse, and praying hands over the globe on the reverse. This coin was issued on the occasion of the Nuremberg Execution Day , there are also pieces of four ducats. It was not uncommon for particularly high denominations to be crafted as cliffs, and the unusual shape was often used for coins issued on a special occasion.

In 1700 a whole series of square gold cliffs were minted in ducat currency in Nuremberg. The front of the coins bore a flying dove over three coats of arms, and on the reverse a depiction of a lamb with a waving flag over a globe; they were made in denominations of 1/16 ducats to three ducats. In addition, there were round gold coins with the same motif, some with a later minting year, also 1/32 ducats, and silver cliffs. This edition was intended to mark the 50th anniversary of the Nuremberg Execution Day. The cliff to a ducat was minted two more times in the middle of the 18th century. Ducats with the same allegorical representation, the “Lamb of God on the Globe”, existed in Nuremberg from 1632 to 1806. Because of their motif, they are called “lamb ducats” or “lamb linducats”, other names are “peace wish ducats” and after the issue according to the custom of giving them away at the turn of the year, "New Year's Ducat".

Apart from the mentioned re-mintings, the gold cliff from 1717 with a value of 2 ducats was the last Nuremberg coin made as a cliff . This issue pays tribute to Martin Luther and the 200th anniversary of the Reformation, the front shows a hand over a candlestick and the inscription on the back reads "Martinus Lutherus Theologiae Doctor". This lettering is also a chronogram which, when resolved, gives the year 1717.

Japan in the 16th to 19th centuries

The first coins reached Japan in the first centuries after Christ from China of the Han Dynasty . However, it is believed that these coins were not yet considered a currency in Japan, but were considered precious gifts because of their precious metal content. The first coins made in Japan date from the late seventh century, they were round coins made of copper with a square hole in the center. A short time later, round coins made of a 95 percent silver alloy with a round hole in the middle followed.

In the 14th century, Japan's foreign trade was carried out in Chinese coins. Archaeologists found 8 million coins weighing 28 tons in a Chinese ship that sank off Korea in 1323 and was en route to Japan. Nevertheless, there was also coin production in Japan for internal trade; the coins produced were initially only copies of Chinese coins. In the centuries that followed, rice repeatedly replaced coins as currency because the quality of the coins was poor and people did not trust the currency system. Taxes were still levied on rice in the early 17th century. From the end of the 16th century, a regulated coinage developed in Japan. With a few exceptions, only a few types of coins have been produced since then. Until the middle of the 19th century, the most common execution was the round coin with a square hole, after which there were rectangular cliffs made of silver or gold. Due to the differences in the inscriptions, from which the names of the rulers and the years of minting emerge, a great variety has arisen. In the case of the silver and gold cliffs, designs were often retained over generations; a cliff into a bu was made unchanged from 1736 to 1818. With the beginning of the Meiji period in 1868, the production of cliffs in Japan ended.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, local authorities could get permission to mint their own coins for use within their jurisdiction. Such coins were often cliffs if they were emergency coins , also made of lead or iron. In 1784, the Sendai region was given permission to mint coins for five years to counter the economic consequences of a famine in northern Japan. Because of the large numbers that were minted, these copper cliffs came into circulation at 1 month outside the region.

Electorate of Saxony

One of the first cliffs in the Electorate of Saxony , which was issued as a shooting jewel, was a golden memorial cliff, which was also minted as a round coin, as imperial guilder at 21 groschen (1584) . Later, in the 16th and 17th centuries, a large number of silver cliffs were issued to honor special occasions. There were also commemorative round coins ; these were often issued parallel to the cliffs in the same design and with the same nominal values. In the second half of the 17th century, the memorial cliffs of Saxony included some editions that referred to shooting competitions. These issues are to be seen in connection with the inclination of the Saxon electors for shooting sports and with the shooting cliffs popular in the 17th and 18th centuries , which were not coins but medals. Some of these commemorative coins for shooting competitions indicate with their inscriptions that they were intended as winners' prizes.

The following table lists examples of Saxon silver cliffs with the occasions for their issue:

| year | Face value | material | Reason for issue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1614 | 1 thaler, 2 thaler | silver | Baptism of August, son of Elector Johann Georg I. |

| 1615 | 1 thaler, 2 thaler | silver | Baptism of Christian, son of Elector Johann Georg I. |

| 1630 | 1 thaler, 2 thaler | silver | Marriage of Maria Elisabeth, daughter of Elector Johann Georg I, with Friedrich III. from Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf |

| 1662 | 1 thaler | silver | Wedding of Erdmuth Sophie, daughter of Elector Johann Georg II. , With Christian Ernst von Brandenburg-Bayreuth |

| 1669 | 1 thaler | silver | Birth of Johann Georg IV., Grandson of Elector Johann Georg II. |

| 1676 | 3 thalers | silver | Bird shooting in Dresden, was also awarded as a prize |

| 1678 | 1 thaler | silver | Inauguration of the new shooting range in Dresden (front: bust of the elector, back: inscription) |

| 1678 | 1 thaler | silver | "Hercules shooting" for the inauguration of the Schützenhaus in Dresden (coat of arms on the front, Hercules on the back) |

| 1679 | 1 thaler | silver | Shooting on the occasion of the peace of Nijmegen |

| 1693 | 1 thaler | silver | Award of the British Order of the Garter to the Elector Johann Georg IV. |

| 1697 | 1 thaler | silver | Rifle shooting at the carnival |

| 1728 | 1 thaler | silver | State visit by King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia |

Kingdom of Sweden 1624–1768

The Kingdom of Sweden manufactured square or rectangular copper coins between 1624 and 1768. The background was the lack of silver and gold, and the country's wealth of copper. First the Fyrk , minted from silver since 1575 , with 1/4 ore the smallest coin at the time, was minted as a cliff for two years, in 1624 and 1625. Further circulation coins with small face values followed in the following years; at the same time cliffs of silver or gold were minted.

The copper plate coins issued in high denominations from 1644 on were designed as bullion coins , despite the low value of the material , and had the same face values as silver and gold coins. This led to formats of around 7.5 × 7.5 cm to around 27 × 68 cm. Regardless of their weight and unwieldiness, the coins were legal tender, used both in international trade and in trade within Sweden and Finland. The Swedish Copper Cliffs are coveted collectibles, and some of the higher levels are only available as unique items in museums. The largest coin ever issued is the 10 Daler plate coin, made in 1644 and 1645.

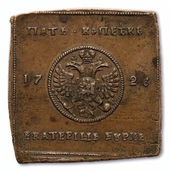

Russian Empire 1725–1727

The Russian Tsarina Catherine I had a number of roughly square-shaped copper coins struck from 1725 to 1727 in denominations of one kopeck to one ruble . The copper content of the coins corresponded to their face value, so that the higher denominations were large and heavy. The Swedish copper cliffs from 1702 apparently served as a model for the design of the coins. As with many Russian coins from the 18th and 19th centuries, there are nowodeli from the copper cliffs ( new strikes ; singular Nowodel , Russian "new production"), these are replicas for collectors' purposes that were made with the original stamps in Russian mints. Novodeli are difficult to distinguish from the original coins , but unlike counterfeits they have a value among coin collectors .

California Territorial Coins 1849–1882

In the 19th century, the US states were prohibited from minting their own coins. However, the prohibition did not extend to private individuals or their companies, provided that the design of the coins prevented confusion with government coins. The remoteness of many regions of the United States often resulted in an inadequate supply of the coins needed to keep the trade going. In some states or territories of the USA, including California, coins were produced and put into circulation outside of state control. These coins are now known as territorial gold , pioneer gold or private gold and are coveted by American coin collectors because of their rarity.

In the mid-19th century, California's population grew rapidly, partly because of the gold rush . American and foreign coins were used in trade, but their numbers were too few to meet demand. At first, gold dust was used as a means of payment, but the prospectors received too little for their gold. Goldsmiths began to make round and octagonal pieces of gold with a face value of 0.25 to 1 dollar at the latest in 1852. The minting of this "little" Californian gold was prohibited by a federal law of 1864 that was not enforced in California until 1883. Around 25,000 of these coins still exist today in 500 variants, which are differentiated by coin collectors. In the years from 1871 in particular, the gold content was significantly lower than the face value of the gold pieces, and the gold pieces were already forged in the 19th century, so in 1890 a forger's workshop was opened in New York.

Gold pieces with denominations of more than one dollar, up to 50 dollars, have been in the making since August 1849 in the company of New York gold inspector John Little Moffat , who had set up a private gold testing office in San Francisco earlier that year. Other companies followed, always under the supervision of the US Treasury. Moffat had signed a contract with the Treasury at the end of 1850, with which he was assigned the duties of a state gold inspector. From January 1, 1851, Moffat minted his coins as the "Provisional Mint of the USA", but his products were not official coins. In February 1852 Moffat left his company to do business in connection with diving bells. Under new management, his company became the - though still private - "United States Assay Office of Gold". This operated until December 1853, after which a state mint was established in San Francisco. Territorial gold was minted until 1855 and, with a few exceptions, the “large” coins were distinguished by the fact that their gold content was equivalent to their face value. Territory coins were also issued in other US territories with significant gold production, but the octagonal cliffs were characteristic of California.

Cliffs in the 20th century

Belgium under German occupation during the First World War

With the onset of World War I, the population in Belgium began hoarding metal money, including small 5, 10 and 25 centime nickel coins, which were then withdrawn from circulation. In addition, the German occupying forces confiscated the cash holdings from banks, for example in Liège. As a first measure to secure the circulation of money, the Belgian National Bank printed banknotes of low denominations, down to one and two Belgian francs. Because the Belgian National Bank had brought its fit banknotes and gold reserves to London, the German occupying power lifted their issuance privilege and transferred it to the “Société générale” bank, whose banknotes were valid currency. In addition to the banknotes from this bank, as early as August 12, 1914, just under a week after the German invasion, 485 Belgian municipalities issued emergency money in paper form to supply the population and to cover the high financial burdens of the municipalities caused by the war.

The city of Ghent was occupied on October 12, 1914. On November 7, 1914, the city council of Ghent decided to issue emergency money notes to the value of 1.6 million Belgian francs with a face value of 5, 20 and 100 francs, which were to be redeemed at the municipality from January 1, 1916. The issuance of these first 1.6 million francs had only been able to satisfy the city treasury's increased need for money for a short time due to the necessary support for refugees and the unemployed. By the end of 1915, almost 20 million francs were issued in eight tranches, now notes of 50 centimes and two francs, as well as, on the basis of a council resolution of April 19, 1915, “war coins” made of brass-coated iron at 50 centimes , 1 Franc and 2 Franc with the currency indication “Stad-Cent” and the inscription “Ville de Gand”. The 50 centimes and 2 francs coins were square cliffs. With the first issue of emergency money in the form of coins , the city council, with a view to coin collectors and the value of the coins as souvenirs, assumed that the guarantee of return stamped on the coins would often not be used after a certain date.

On March 12, 1917, the city council decided to continue spending emergency money in its ongoing financial crisis. Now there were also round coins for 5 francs. In 1917, the currency denominations were "Francs" and "Francs" and the repayment guarantee was in French and Dutch. Due to a ban imposed by the German "civil administration" during the minting of the coins, in 1918 the coins only had the currency indication "Frank" and a Dutch text. On February 18, 1918, the city council decided to issue 200,000 francs in coins of 0.25 francs and a further 100,000 francs in coins of 0.10 francs. Eight days later, the German authorities banned the use of metal. The coins were issued in the form of round cardboard disks . By the end of the war, the city of Ghent had circulated around 46 million francs of emergency money, including around 1.5 million coins worth almost 3.5 million francs. This made it the most productive municipality, ahead of the city of Ostend, which issued emergency money for 16 million francs.

Another issue of "coins" without the character of a means of payment took place in 1920, when coins made of a copper alloy with face values of one and two francs were sold for charitable purposes. It was a cliff to a franc with the stated year of issue 1915; however, the war coins for a franc were round. It is possible that these cliffs were minted as early as 1915 and banned by the occupying forces because, unlike the other coins, they were made of copper. The coin from 1920 for 2 francs, on the other hand, was round and struck as the year of issue in 1918. The previous 2 franc coins were cliffs, with the year 1915 only.

Kingdom of the Netherlands and Dutch colonies

From 1913 to 1940, the five cents circulation coin in the Netherlands was minted as a square cliff made of a copper-nickel alloy. In the years 1941 to 1943, square zinc cliffs also followed under the German occupation, which were very simple in design and can thus be recognized as emergency coins . In various Dutch colonies and overseas territories, currency coins were repeatedly issued as cliffs in the 20th century; the five cents coins issued on Curacao in 1943 and 1948 had the same design as the coins struck in the motherland from 1913–1940. The coins of the Netherlands Antilles at five cents, which appeared between 1957 and 1970, were also designed. In 1971 the design was replaced with a more modern one, while maintaining the shape. In 1976 and 1977, two octagonal gold bullion coins with a face value of 200 guilders followed, and from 1989 a square currency coin at 50 cents, which was similar to its predecessors at five cents. With these last three issues, the cliffs on the Dutch Antilles have left the realm of everyday money and have become collector's coins, because since the minting year 1993, the coins at 50 cents have only been issued with complete sets of coins in several years , i.e. only produced for the collector's market .

Argentine Republic 1993

On January 1, 1993, the Argentine Peso at 100 Centavos was introduced as the new currency . The 1 Centavo coin with the minting year 1992 is made of aluminum-bronze and exists in two variants. The minting for the year 1992, for the first issue, was octagonal; From the minting year 1993, round coins were made. This coin is a low-value coin in circulation and as such an object of everyday use without reference to the collector's market.

Republic of Chile to date

The Republic of Chile has been issuing eight- or ten-sided circulation coins in small and medium denominations for many years and to this day. In the ascending order of denominations, the embossing metal and the shapes are chosen in such a way that it is difficult to mix up the coins in everyday life. The one and five peso coins are octagonal, but the one peso coins are made of aluminum and the five peso coins are made of an aluminum-bronze alloy, the decagonal coin of 50 peso differs from the coins of 10 and 100 peso by Shape and weight.

Republic of Armenia since 2000

The Republic of Armenia is an example of a country that today issues large numbers of unusually shaped or colored commemorative coins, including cliffs . The state, founded in 1991, has been issuing commemorative coins made of gold or silver since 1994; the first cliff was an octagonal silver cliff "New Millennium" in 2000 with a depiction of St. George with a face value of 2,000 dram. One of the last editions in 2012 was, as the fourth cliff in the “Artists” series, a rectangular silver cliff in the format 28 × 40 mm, with a face value of 100 dram , with which the Soviet film director Sergei Parajanov is to be honored. At least two more cliffs are planned for 2013.

In addition to national motifs, there are also issues in Armenia's issuing program that target the collector's market without reference to the country, such as a series of silver coins minted since 2008 with depictions of internationally known football players; including Franz Beckenbauer in 2009. The illustrated cliff from the “Artists” series was proposed and minted by the Polish mint, which also mints coins for New Zealand, Niue and Belarus as part of the international “Artists of the World” series. Almost all other special coins come from the Royal Netherlands Mint . The contact between Armenia and both mints is handled by Coin Invest Trust in Liechtenstein, which is one of the most important companies in the international trade in collector coins. The silver and gold coins of Armenia are legal tender, but are also referred to as “collector coins” by the Armenian central bank. In a 2011 questionnaire aimed at collectors and numismatists, the central bank not only asked about the preferred metal and the topics of the desired coin issues. In addition, questions are asked about the attitude of the collector towards collector coins that are decorated with embedded precious stones or colored imprints or that are embossed in unusual shapes such as polygons, squares or ovals.

A comparison of the denominations shows that the issue of the commemorative coins of Armenia, including the cliffs, is not based on the population's need for circulation coins. The aluminum course coins minted in 1994 had value levels from 10 Luma (0.1 Dram) to 10 Dram, while the special coins made of silver and gold that were issued until 2002 had value levels from 5 Dram to 100,000 Dram. The circulation coins issued since 2003 have face values of 10 to 500 dram, compared to 100 to 50,000 dram for collector coins. The Armenian Central Bank operates a shop in Yerevan under the name "Numismatist". The following table shows the circulation, face value and retail prices of some collector coins:

| coin | Year of issue | material | Edition | Face value | Selling price | factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iwan Konstantinowitsch Aiwasowski, rectangular cliff | 2006 | silver | up to 5,000 | 100 dram | - | - |

| Franz Beckenbauer, round, with colored imprint | 2009 | silver | up to 200,000 | 100 dram | 22,600 dram | 226 |

| Sergei Parajanov, rectangular cliff | 2012 | silver | up to 5,555 | 100 dram | - | - |

| 20 years of the Armenian Armed Forces, octagonal cliff | 2012 | silver | 500 | 1,000 dram | 30,000 dram | 30.0 |

| 20 years of the Armenian Armed Forces, octagonal silver cliff and round gold coin in a set (the edition refers to the minted edition, not the sets) | 2012 | Gold Silver | 500 each | 11,000 dram | 236,000 dram | 21.5 |

| 150th birthday of Stepan Aghajanian, rectangular cliff | 2013 | silver | 500 | 100 dram | 35,500 dram | 355.0 |

| Ara Beqaryan's 100th birthday, rectangular cliff | 2013 | silver | 500 | 100 dram | 35,500 dram | 355.0 |

Coins made of precious metals with high denominations are issued by many countries. One example are the gold coins worth 200 euros from the Federal Republic of Germany. In the case of investment coins of this type , the face value is in an appropriate proportion to the precious metal content of the coins. The same applies to the selling price, and the resale value fluctuates with the price of gold or silver. Investment coins can also be made as cliffs. However, the majority of the cliffs issued by Armenia in recent years cannot be found in the local central bank's sales offer and the sales prices demanded by coin dealers there and worldwide are many times their face value. An “investment” in such products, which are intensely advertised, amounts to the total loss of the investment in view of the resale value of such coins. The Republic of Armenia is just one example of a large number of countries whose coin programs are determined by the international collector's coin market. Since practical considerations in relation to the format of the collector's items do not play a role, but unusual shapes make the embossing even more attractive, modern cliffs will appear in large numbers in the future. The same applies to private issues of “commemorative coins” on special topics or occasions, which are medals without a function as a means of payment.

The same applies to certain cliff-shaped replicas. The minting of the most expensive imperial coin, the commemorative coin for the 400th anniversary of the Reformation in 1917 in the shape of a cliff, is a private piece of work. This is to be understood derogatory here for a product that simulates a special value that it does not have. The piece never existed like this.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Albert R. Frey: A dictionary of numismatic names, their official and popular designations. The American Numismatic Society, New York (NY) 1917, Lemma “Klippe”, Online PDF; 20.7 MB , entire issue, accessed August 22, 2013.

- ↑ a b c Friedrich v. Schrötter et al. (Ed.): Dictionary of coinage. 2nd unchanged edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1970, reprint 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-001227-9 (reprint of the original edition from 1930), Lemma "Klippen".

- ↑ a b c Luck, Johann Jacob: Sylloge numismatum elegantiorum: quae diuersi impp., Reges, principes, comites, respublicae diuersas ob causas from anno 1500 ad annum usq [ue] 1600 cudi fecerunt. Reppianis, Argentinae (= Strasbourg) 1620

- ↑ a b c J. PC Rüder: Attempt to describe the emergency coins that have been minted for several centuries . Johann Christian Hendel , Halle 1791.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Schrötter et al. (Ed.): Dictionary of coinage. 2nd unchanged edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1970, Reprint 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-001227-9 (reprint of the original edition from 1930), Lemma “Siege coins”.

- ↑ Christoph Weigel: Illustration of the non-profit-making main estates of which regents and their servants assigned in times of peace and war, bit on all artists and craftsmen / After every job and job, mostly drawn from life and brought into copper, also according to the origin, usability and memorable features, briefly, but thoroughly described, and presented in a completely new way. Regensburg 1698, sheet “Der Müntzer”, online DFG viewer , accessed on August 20, 2013

- ↑ a b Percy Gardner: The types of Greek coins. An archaeological essay. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1883, Online PDF; 14,180 kB , accessed on August 22, 2013.

- ↑ Lenelotte Möller and Manuel Vogel: The natural history of Gaius Plinius Secundus. 2 volumes. Marixverlag, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-86539-144-5 .

- ↑ Carl von Ernst: The art of coinage from the oldest times to the present. In: Numismatic Journal. Vol. 12, 1880, pp. 22-67, online PDF; 25.1 MB , entire volume, accessed August 22, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d Gustav Zeller: Des Erzstiftes Salzburg minting law and minting together with a list of the Salzburg coins and medals related to Salzburg. Second increased and improved edition. KK Hofbuchhandlung Heinrich Dieter, Salzburg 1883, Online PDF; 7,415 kB , accessed on August 23, 2013.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Schrötter et al. (Ed.): Dictionary of coinage. 2nd unchanged edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1970, reprint 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-001227-9 (reprint of the original edition from 1930), lemmas "Klippwerk" "," Spindelwerk "," Taschenwerk ", and" Walzenprägewerk ".

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce, George S. Cuhaj and Merna Dudley (Eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins. Seventeenth Century. 1601-1700. 4th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2008, ISBN 978-0-89689-708-3 , pp. 89-108 (chapter "Austrian States - Salzburg"), pp. 659-669 (chapter "German States - Nurnberg" ), Pp. 762–794 (chapter “German States - Saxony”).

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce, Fred J. Borgmann and Elizabeth A. Burgert (Eds.): Standard Catalog of German Coins. 1601 to present, including colonial issues. 2nd edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 1998, ISBN 0-87341-644-9 , pp. 599–609 (chapter “German States - Munster”), pp. 620–637 (chapter “German States - Nurnberg”), Pp. 810–864 (chapter “German States - Saxony”).

- ↑ a b Ch. Gilleman: Monnaies de nécessité et bons de caisse de la ville de Gand 1914-1919. In: Revue belge de numismatique et de sigillographie , vol. 71, 1915-1919, pp. 230-250 and plate 2, online PDF; 850 kB , accessed on August 23, 2013.

- ↑ George S. Cuhaj (Ed.): 2013 Standard Catalog of World Coins 1901–2000. 40th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2012, ISBN 978-1-4402-2962-6 , p. 222 (chapter “Belgium - Ghent”), pp. 1589–1599 (“Netherlands”).

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce and Merna Dudley (Eds.): 2011 Standard Catalog of World Coins. 2001 date. 5th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2010, ISBN 978-1-4402-1160-7 .

- ↑ without author: The Bavarian Numismatic Society 1993–1995. In: Yearbook for Numismatics and Monetary History. Vol. 44, 1994, ISSN 0075-2711 , pp. 233-239, here brief mention of an individual case on pp. 235-236, online PDF; 32.1 MB , entire volume, accessed August 17, 2013.

- ↑ George Francis Hill: Historical Greek Coins. The beginnings of coinage in Asia minor seventh century BC Archibald Constable and Company, London 1906, Online PDF; 10.5 MB , accessed August 22, 2013.

- ^ Charles Francis Keary: The Morphology of Coins. Part I - The Greek Family. In: The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society. Third Series, Vol. V, 1885, pp. 165-198, Online PDF; 22.9 MB , entire volume, accessed August 22, 2013.

- ^ John H. Kroll and Nancy M. Wagoner: Dating the Earliest Coins of Athens, Corinth and Aegina. In: American Journal of Archeology. Vol. 88, 1984, ISSN 0002-9114 , pp. 325-344.

- ^ Edward James Rapson: Coins of the Graeco-Indian Sovereigns Agathocleia, Strato I Soter, and Strato II Philopator. In: George Francis Hill et al. (Ed.): Corolla numismatica. Numismatic essays in honor of Barclay V. Head. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1906, pp. 245-258, Online PDF; 27.5 MB , entire volume, accessed August 22, 2013.

- ^ Theodore Reinach: Jewish coins. Lawrence and Bullen, London 1903, pp. 25-26, Online PDF; 3,530 kB , accessed on August 22, 2013.

- ↑ John Ward: Greek Coins and their parent cities. John Murray, London 1902, p. 138, Online PDF; 27.9 MB , accessed August 22, 2013.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Schrötter et al. (Ed.): Dictionary of coinage. 2nd unchanged edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1970, reprint 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-001227-9 (reprint of the original edition from 1930), Lemma “Aes rude”.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Schrötter et al. (Ed.): Dictionary of coinage. 2nd unchanged edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1970, reprint 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-001227-9 (reprint of the original edition from 1930), Lemma “Aes signatum”.

- ^ Heinrich Dressel: Italy. Aes rude, aes signatum, aes grave. The minted coins from Etruria to Calabria (= Royal Museums in Berlin. Description of the ancient coins. Third volume. Section I). Berlin: W. Spemann 1894, pp. 1–33, addendum pp. IX-X and panels AH, online PDF; 19.8 MB , accessed August 22, 2013.

- ^ Albert R. Frey: A dictionary of numismatic names, their official and popular designations. The American Numismatic Society, New York (NY) 1917, lemmas “Aes”, “Aes Grave”, “Aes Rude”, “Aes Signatum”, online PDF; 20.7 MB , entire issue, accessed August 22, 2013.

- ↑ Gunther Kraft: Chemical-analytical characterization of Roman silver coins. Dissertation, Department of Materials and Geosciences at the Technical University of Darmstadt, Darmstadt 2005.

- ^ Charles Francis Keary: The Morphology of Coins. Part II - The Roman Family. In: The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society. Third Series, Vol. IV, 1886, pp. 41-95.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Schrötter et al. (Ed.): Dictionary of coinage. 2nd unchanged edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1970, reprint 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-001227-9 (reprint of the original edition from 1930), Lemma “Aes grave”.

- ^ Edward James Rapson: Catalog of the coins of the Andhra dynasty, the Western Ksatrapas, the Traikutaka dynasty, and the Bodhi dynasty. Trustees of the British Museum, London 1908, Online PDF; 22.9 MB , accessed August 22, 2013.

- ↑ James Gibbs: On Some Rare and Unpublished Coins of the Pathan and Mogul Dynasties of Delhi. In: The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society. Third Series, Vol. V, 1885, pp. 213–228 (including about two gold cliffs from the 14th and 16th centuries), online PDF; 22.9 MB , entire volume, accessed August 22, 2013.

- ^ Without author: Kölner Münzkabinett - Tyll Kroha. 98th auction on October 22nd and 23rd, 2012. (preliminary auction report). In: money trend Volume 44 , Issue 10, 2012 ISSN 1420-4576 , pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce, George S. Cuhaj and Merna Dudley (Eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins. Seventeenth Century. 1601-1700. 4th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2008, ISBN 978-0-89689-708-3 , pp. 940-1022 (chapter “India”).

- ↑ Chester L. Krause, Clifford Mishler and Colin R. Bruce (eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins. Eighteenth Century. 1701-1800. Third edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2002, ISBN 0-87349-469-5 , pp. 611-765 (chapter “India”).

- ^ Colin R. Bruce, George S. Cuhaj and Merna Dudley (Eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins 1801-1900. 5th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2006, ISBN 978-0-89689-373-3 , pp. 538-704 (chapter “India”).

- ↑ George S. Cuhaj (Ed.): 2013 Standard Catalog of World Coins 1901–2000. 40th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2012, ISBN 978-1-4402-2962-6 , pp. 1082–1134 (chapter “India”), pp. 1659–1664 (chapter “Pakistan”).

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce and Merna Dudley (Eds.): 2011 Standard Catalog of World Coins. 2001 date. 5th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2010, ISBN 978-1-4402-1160-7 , pp. 247-251 (chapter “India”).

- ↑ Friedrich v. Schrötter et al. (Ed.): Dictionary of coinage. 2nd unchanged edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1970, reprint 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-001227-9 (reprint of the original edition from 1930), Lemma “Klipping”.

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce, George S. Cuhaj and Merna Dudley (Eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins. Seventeenth Century. 1601-1700. 4th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2008, ISBN 978-0-89689-708-3 , pp. 89-108 (chapter “Austrian States - Salzburg”).

- ↑ a b Hartwig Neumann: The Jülich Notklippen from 1543, 1610, 1621/22. City of Jülich and Kreissparkasse Jülich, Jülich 1974.

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce, George S. Cuhaj and Merna Dudley (Eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins. Seventeenth Century. 1601-1700. 4th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2008, ISBN 978-0-89689-708-3 , pp. 564-566 (chapter “German States - Julich”).

- ↑ Robert Ball Nachf. (Ed.) - Auction catalog of the collection Bernhard Heilbrunn † Gotha. Coins from Saxony, gold coins and rarities. Catalog for auction on October 5, 1931, Berlin 1931

- ↑ Walter Haupt: Saxon coinage. Berlin 1974, pp. 275 and 279

- ^ Govert George van der Hoeven: Geschiedenis the vesting Breda. Broese & Comp., Breda 1868

- ^ A b Hans-Jörg Kellner: The coins of the free imperial city of Nuremberg. Part II: The silver coins. In: Yearbook for Numismatics and Monetary History Volume 7, 1956, ISSN 0075-2711 , pp. 139–249, online PDF; 33,380 kB , accessed on August 18, 2013.

- ^ A b c Hans-Jörg Kellner: The coins of the free imperial city of Nuremberg. Part I: The gold coins. In: Yearbook for Numismatics and Monetary History Volume 3 and 4, 1952/53, ISSN 0075-2711 , pp. 113–159, online PDF; 26,330 kB , accessed on August 18, 2013.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Schrötter et al. (Ed.): Dictionary of coinage. 2nd unchanged edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1970, reprint 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-001227-9 (reprint of the original edition from 1930), Lemma “Lämmlein-, Lamm- oder Neujahrsdukaten”.

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce, Fred J. Borgmann and Elizabeth A. Burgert (Eds.): Standard Catalog of German Coins. 1601 to present, including colonial issues. 2nd edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 1998, ISBN 0-87341-644-9 , pp. 620-637 (chapter “German States - Nurnberg”).

- ↑ without author: directory of some very rare thalers and coins, which are to be publicly sold in July 1763 here in Gotha for cash payment to the highest bidders. Gotha 1763, p. 17

- ↑ a b Shin'ichi Sakuraki: A Brief History of Pre-modern Japanese Coinage. In: The British Museum (Ed.): Catalog of the Japanese Coin Collection (pre-Meiji) at the British Museum, with special reference to Kutsuki Masatsuna. British Museum Research Publication no. 174. The British Museum, London 2010, ISBN 978-0-86159-174-9 Online PDF; 4,740 kB , accessed on August 25, 2013.

- ↑ Chester L. Krause, Clifford Mishler and Colin R. Bruce (eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins. Eighteenth Century. 1701-1800. Third edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2002, ISBN 0-87349-469-5 , pp. 888-893 (chapter “Japan”).

- ^ Colin R. Bruce, George S. Cuhaj and Merna Dudley (Eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins 1801-1900. 5th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2006, ISBN 978-0-89689-373-3 , pp. 781-793 (chapter “Japan”).

- ↑ Friedrich v. Schrötter et al. (Ed.): Dictionary of coinage. 2nd unchanged edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1970, reprint 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-001227-9 (reprint of the original edition from 1930), Lemma “Schießprämien”.

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce, George S. Cuhaj and Merna Dudley (Eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins. Seventeenth Century. 1601-1700. 4th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2008, ISBN 978-0-89689-708-3 , pp. 762-794.

- ↑ Chester L. Krause, Clifford Mishler and Colin R. Bruce (eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins. Eighteenth Century. 1701-1800. Third edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2002, ISBN 0-87349-469-5 , pp. 502-522 (chapter “German States - Saxony”).

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce, George S. Cuhaj and Merna Dudley (Eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins. Seventeenth Century. 1601-1700. 4th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2008, ISBN 978-0-89689-708-3 , pp. 1337-1354 (chapter “Sweden”).

- ↑ Chester L. Krause, Clifford Mishler and Colin R. Bruce (eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins. Eighteenth Century. 1701-1800. Third edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2002, ISBN 0-87349-469-5 , pp. 1125–1140 (chapter “Sweden”).

- ^ Albert R. Frey: A dictionary of numismatic names, their official and popular designations. The American Numismatic Society, New York (NY) 1917, Lemma “Ruble, or Ruble”, online PDF; 20.7 MB , entire issue, accessed August 22, 2013.

- ↑ Chester L. Krause, Clifford Mishler and Colin R. Bruce (eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins. Eighteenth Century. 1701-1800. Third edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2002, ISBN 0-87349-469-5 , pp. 1055-1088 (chapter “Russia”).

- ^ Colin R. Bruce, George S. Cuhaj and Merna Dudley (Eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins 1801-1900. 5th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2006, ISBN 978-0-89689-373-3 , pp. 1127–1138 (chapter “US Territorial Gold”).

- ↑ Ole Lars Jacobsen: Het Gemeentegeld van Gent tijdens de Oorlog 1914-1918. In: Revue belge de numismatique et de sigillographie , vol. 126, 1980, pp. 210-216, Online PDF; 3,980 kB , accessed on August 23, 2013.

- ↑ George S. Cuhaj (Ed.): 2013 Standard Catalog of World Coins 1901–2000. 40th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2012, ISBN 978-1-4402-2962-6 , p. 222 (chapter “Belgium - Ghent”).

- ↑ George S. Cuhaj (Ed.): 2013 Standard Catalog of World Coins 1901–2000. 40th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2012, ISBN 978-1-4402-2962-6 , pp. 658–659 (chapter “Curacao”), pp. 1589–1599 (chapter “Netherlands”), pp. 1599– 1604 (chapter "Netherlands Antilles").

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce and Merna Dudley (Eds.): 2011 Standard Catalog of World Coins. 2001 date. 5th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2010, ISBN 978-1-4402-1160-7 , pp. 391-393 (chapter “Netherlands Antilles”).

- ↑ George S. Cuhaj (Ed.): 2013 Standard Catalog of World Coins 1901–2000. 40th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2012, ISBN 978-1-4402-2962-6 , pp. 91-100 (chapter “Argentina”).

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce and Merna Dudley (Eds.): 2011 Standard Catalog of World Coins. 2001 date. 5th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2010, ISBN 978-1-4402-1160-7 , pp. 114–115 (chapter “Chile”).

- ↑ George S. Cuhaj (Ed.): 2013 Standard Catalog of World Coins 1901–2000. 40th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2012, ISBN 978-1-4402-2962-6 , pp. 100-103 (chapter “Armenia”).

- ↑ a b c Central Bank of Armenia (ed.): Collector Coins of the Republic of Armenia 2012. Central Bank of Armenia, Yerevan 2013, online PDF; 3,410 kB , accessed on August 17, 2013.

- ↑ without author: Questionnaire for collectors and numismatists. Central Bank of Armenia, undated (Yerevan) 2011, Online PDF; 526 kB , accessed on August 17, 2013.

- ↑ Central Bank of Armenia: Investment coins . Central Bank of Armenia, accessed August 17, 2013

- ↑ a b Colin R. Bruce and Merna Dudley (Eds.): 2011 Standard Catalog of World Coins. 2001 date. 5th edition. Krause Publications, Iola (WI), USA 2010, ISBN 978-1-4402-1160-7 , pp. 18-21 (chapter “Armenia”).

- ↑ a b without author: The commemorative coins that are available for sale in the CBA "Numismatist" saloon. Central Bank of Armenia, Yerevan 2013, Online PDF; 35 kB ( Memento of the original from April 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed August 17, 2013.

- ↑ without author: Armenian collector coins issue program 2012–2013. Central Bank of Armenia, undated (Yerevan) undated (2012), Online PDF; 24 kB , accessed on August 17, 2013.

- ^ Siegfried Bauer: German Coins 1871 to 1932 ... (1976), p. 49

literature

- Albert R. Frey: A dictionary of numismatic names, their official and popular designations. The American Numismatic Society, New York (NY) 1917, Online PDF; 21,215 kB , accessed on August 22, 2013.

- Friedrich v. Schrötter et al. (Ed.): Dictionary of coinage. 2nd unchanged edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 1970, reprint 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-001227-9 (reprint of the original edition from 1930).