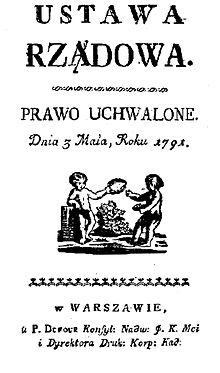

Constitution of May 3, 1791

The constitution of May 3, 1791 ( Polish Konstytucja trzeciego maja , Lithuanian Gegužės trečiosios konstitucija ) was adopted on May 3, 1791 by the Sejm , the parliamentary assembly of Poland-Lithuania (see also Rzeczpospolita ), in the Warsaw Royal Castle . According to Norman Davies , it is considered "the first [constitution] of its kind in Europe" to be passed by a parliament . Other sources refer to it as the second oldest modern constitution in Europe after the one published in 1755Constitution of Corsica or as the third oldest modern constitution in the western world after the constitution of the United States of America passed on September 17, 1787 .

In terms of content, the constitution was based on the ideas of the Enlightenment , the declaration of human and civil rights and the reform discourses that have been taking place in Poland itself since the 16th century. In memory of the constitution and its historical significance, May 3rd is the most important national holiday in Poland , alongside November 11th, Independence Day commemorating the regaining of state sovereignty in 1918 .

prehistory

After a long period of political, economic and cultural prosperity, Poland-Lithuania had been embroiled in several political and military conflicts with its expansionist neighboring states from the 17th century onwards, against which it had to wage numerous grueling defensive wars. The defeats and devastation as well as internal political conflicts between the political currents and institutions drove the country to the brink of ruin. These disputes included:

- several Russian-Polish wars ( 1609–1618 , 1632–1634 , 1654–1667 , 1792 and 1794 )

- several wars against the Ottoman Empire ( 1620–1621 , 1633–1634 , 1672–1676 , 1683–1699 - culminating in the Second Turkish Siege of Vienna in 1683)

- an uprising in the Ukraine under Hetman Bohdan Chmielnicki from 1648 - the end result was a weakening of Poland through the secession of eastern Ukraine under the Zaporozhian Cossacks in favor of Russia in 1654

- several Swedish-Polish wars ( 1600–1629 , 1655–1660 and 1700–1721 ) - mostly dynastic conflicts of the Wasa

- the War of the Polish Succession 1733–1735 / 38;

- the Seven Years War 1756–1763;

- numerous uprisings by the Cossacks and countless raids and raids by the Crimean Tatars 1666–1671

- internal quarrels through aristocratic confederations in the course of the 17th / 18th centuries Century

Especially as a result of the wars, Poland-Lithuania had lost its supremacy in Central Eastern Europe . This was passed to Russia under the Romanovs and to Brandenburg-Prussia under the Hohenzollern .

The electoral monarchy Poland-Lithuania increasingly became a "plaything" of different interests both internally and externally and slowly fell into decadence , agony and political anarchy . The signs of general decline manifested themselves in the permanent blockade of parliament by means of the Liberum Veto , the formation of noble alliances (so-called confederations) against the interests of the state and the king, when, for example, the magnates curtailed their rights to golden freedom by the king saw.

Careful reform efforts by King Stanisław August Poniatowski , who in 1764 after the death of August III. was elected king, led to the intervention of Russia, who bowed to Stanisław August, against which the Confederation of Bar , an armed group of opposition country nobles against both the king and Russia, was formed.

Their military defeat resulted in the First Partition of Poland in 1772 . In the shrunken state, these events ultimately led to a strengthening of the reform camp around the Enlightenmentists Hugo Kołłątaj , Stanisław Staszic and Ignacy Potocki , so that serious internal reforms became possible.

Constitution

During the four-year Sejm (1788–1792), opponents of a close relationship with Russia prevailed. This created a viable majority in order to enforce the state's ability to act again through domestic political reforms. In terms of foreign policy, Prussia's benevolent attitude was positive. The internal and external political constellations made reforms possible, which culminated in the drafting and approval of the constitution by the Sejm. It was proclaimed on May 3, 1791 by the king.

The Constitution

Basics

The Polish constitution of 1791 took up central aspects of the French Enlightenment , but also older internal Polish reform discussions. The principle of popular sovereignty goes back to Jean-Jacques Rousseau , who in 1772 did not finish his reflections on the government of Poland and its proposed reform until after the First Partition . The Sejm was declared to be the embodiment of the “omnipotence of the nation”. With the introduction of the “Landbotenkammer”, the wealthy bourgeoisie received a political say for the first time alongside the nobility. This right was still denied to the peasants. After all, they benefited from the general equality of rights that previously only applied to the nobility and religious institutions. The constitution adopted the principle of the separation of powers ( judiciary , executive and legislative ) from Montesquieu . The government was subjected to parliament. In the Sejm itself, the majority principle was to apply from now on. The liberum veto of the nobility, which in the past had often led to the blockade of Polish domestic and foreign policy, was limited to a few cases. The negative experiences with the electoral monarchy led to the introduction of the hereditary monarchy under the Wettins (Elector Friedrich August III , however, rejected the crown). The influence of the kings within the parliamentary - constitutional monarchy was very limited. According to the constitution, the rights of the king focused on the external representation of the state.

The Holy Roman Catholic Faith was declared the national religion while at the same time guaranteeing freedom of religion for other denominations. Conversions to these were considered apostasy and were forbidden.

Content (excerpts)

- The ruling national religion is and remains the holy Roman Catholic faith with all its rights. The transition from the ruling faith to any other confession is forbidden with the penalties of apostasy. But since this very holy faith commands us to love our neighbor; so we owe it to all people, of whatever creed they may be, to give rest in their faith and the protection of the government. That is why we are hereby ensuring, in accordance with our state decisions, the freedom of all religious customs and beliefs in the Polish lands. (I. Article)

- All violence in human society arises from the will of the nation. (Beginning of Article V)

- The executive power should neither issue nor declare any laws, impose no duties or taxes, under whatever name it may be, make no government bonds, change the division of treasure income made by the Reichstag, declare no wars, no peace, no treaty and none be able to definitively conclude diplomatic acts. It should only be at liberty to engage in temporary negotiations with the foreign courts, to remedy the same temporary and common needs for the security and tranquility of the country; but she is obliged to report on this to the next Reichstag assembly. (Extract from Article VII)

- It seems to our prudence to regulate the succession to the throne on the Polish throne according to the following law: We therefore stipulate that ... the ... reigning Elector of Saxony will reign as king in Poland. The eldest son of the ruling king is to succeed his father on the throne. (Extract from Article VII)

- The judicial power can neither be exercised by the legislative nor by the king [note: the executive power] , but by the magistrates founded and elected to this end. (Beginning of Article VIII)

The above translation passages are taken from: KHL Pölitz, The European Constitutions since 1789, 3rd volume , FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1833.

consequences

The constitution of May 3rd was seen by the neighboring countries of Poland, not least because of the simultaneous events in France , as a threat to their absolutist form of rule and after the Confederation of Targowica and the intervention of Russia, which culminated in the Russo-Polish War of 1792 , repealed by the Kingdom of Prussia under Friedrich Wilhelm II. and the Russian Empire under Catherine II as part of the Second Partition of Poland in 1793. On the occasion of the centenary of the constitution, the history painter Jan Matejko created the painting “The Constitution of May 3, 1791” in 1891 in order to capture the spirit of Europe's first modern constitution.

References

See also

literature

- Georg-Christoph von Unruh : The Polish constitution of May 3, 1791 in the context of the constitutional development of the European states. In: The state . Volume 13, No. 2, 1974, pp. 185-208, JSTOR 43640585 .

- Stanisław Grodziski: The Constitution of May 3, 1791 - the first Polish constitution. In: From Politics and Contemporary History . (APuZ). Volume 37, No. 30/31, 1987, pp. 40-46.

- Helmut Reinalter , Peter Leisching (ed.): The Polish constitution of May 3, 1791 against the background of the European Enlightenment (= series of publications by the International Research Center for Democratic Movements in Central Europe 1770–1850. 23). Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1997, ISBN 3-631-30509-5 .

- Jan Kusber : From project to myth - The Polish May Constitution 1791. In: Journal for historical science . Volume 52, No. 8, 2004, pp. 685-699.

- Israel Bartal : Four-year fair. In: Dan Diner (ed.): Encyclopedia of Jewish history and culture. Volume 6: Ta-Z. Metzler, Stuttgart et al. 2015, ISBN 978-3-476-02506-7 , pp. 288-290.

Web links

- The constitutional text in excerpts (Polish, English and German)

- Text of the constitution of May 3rd in German translation

- Article at www.deutschlandundeuropa.de

Footnotes

- ^ Norman Davies : Europe. A history . Oxford University Press, Oxford et al. 1996, ISBN 0-19-820171-0 , pp. 699 .

- ^ Albert P. Blaustein : Constitutions of the world . Fred B. Rothman, Littletown CO 1993, ISBN 0-8377-0362-X , pp. 15 .

- ↑ Sandra Lapointe, Jan Wolenski, Mathieu Marion, Wioletta Miskiewicz (ed.): The Golden Age of Polish Philosophy. Kazimierz Twardowski's philosophical legacy (= Logic, epistemology, and the unity of science. 16). Springer, Dordrecht et al. 2009, ISBN 978-90-481-2400-8 , p. 4.

- ↑ https://www. britica.com/place/Poland/The-First-Partition

- ↑ Manfred Alexander : Small history of Poland (= Federal Center for Political Education. Series of publications. Vol. 537). Federal Agency for Civic Education, Bonn 2005, ISBN 3-89331-662-0 , p. 158.

Remarks

- ↑ The title of the “first” constitution is not without controversy in the specialist literature and is determined by the question of how the constitution is ultimately defined. Many authors apply different standards here. A constitutional document that is older than both the American and the Polish constitution can be found in Corsica, for example. See: Dorothy Carrington: The Corsican constitution of Pasquale Paoli (1755–1769). In: The English Historical Review . Volume 88, No. 348, 1973, pp. 481-503, JSTOR 564654 .