Northern rock python

| Northern rock python | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Northern rock python ( Python sebae ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Python sebae | ||||||||||||

| ( Gmelin , 1788) |

The northern rock python ( Python sebae ), also known as rock python for short , belongs to the family of pythons (Pythonidae) and is part of the genus of actual pythons ( python ). It differs from the southern rock python by its scaling and patterning features . With secured lengths of over five meters, the northern rock python is one of the largest snakes in the world. Its distribution area extends in Africa south of the Sahara from the west coast to the east coast and south to the north of Angola. Here he lives in a multitude of tropical and subtropical landscapes not too far away from water. It is very adaptable and, as a cultural follower, also colonizes agricultural areas and settlements.

The diet consists of a large number of different vertebrates. In areas with high mammalian populations, large individuals relatively often prey on small antelopes , which can rarely weigh more than 30 kilograms. The python kills its prey by strangling .

description

Physique and teeth

Juvenile animals are quite slim, but with increasing age they become stronger and stronger. In large adult northern rock pythons, the cylindrical body flattens slightly. The broad, triangular, slightly flattened, large head is clearly set off from the neck. The snout is rounded on the top towards the tip. Her nostrils sit at an angle between the top of the head and the side of the head. The tapering prehensile tail makes up between 9 and 14% of the total length in females and between 11 and 16% of the total length in males.

The bit consists of thin, elongated teeth that are continuously pointed and curved towards the throat and become increasingly smaller from the tip of the mouth to the throat. At the front of the upper oral cavity is the intermaxillary bone with two small teeth. The upper jaw bones each have 13 to 16 teeth. Towards the middle of the upper oral cavity, the palatine bone lies parallel to the maxillary bones in front and the wing bone further back . The former has 6 to 7 teeth and the other 8 to 9 teeth. The lower jaws each have 13 to 17 teeth.

Scaling

The top of the head is characteristically covered by large scales: the nasalia (nasal shields) are separated from each other by a pair of square internasalia (intermediate nasal shields) . The subsequent distinctively formed pair of prefrontalia (forehead shields) is separated from the large pair of frontalia (forehead shields) behind it by a series of less, irregular shields . The latter pair can occasionally be partially or completely fused. The Supraoculare (over eye shield) is large and separated in two parts. On the side between the eye and the nostril there are at least three to four Lorealia (rein shields) of different sizes and two Präocularia (forehead shields), of which the lower one is small and irregular in shape. Postocularia (posterior eye shields) exist two to four on both sides. The rostral (nose plate) has, as with most other pythons also two deep Labialgruben . Of the 13 to 16 supralabials (shields of the upper lip), the second and third are provided with fine labial pits. The 19 to 25 infralabialia (lower lip shields ) become increasingly smaller towards the tip of the snout. The two foremost and the three to four rearmost bear fine labial pits. The number of ventralia (belly shields) varies depending on the origin of the individuals between 265 and 283, the number of dorsal rows of scales in the middle of the body between 76 and 98. From the cloaca to the tip of the tail there are 62 to 76 paired subcaudalia (underside shields of the tail). The anal (anal shield) can be undivided or divided.

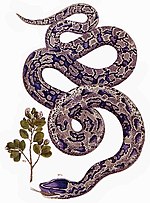

coloring

The basic color ranges from yellow, beige, light brown to gray. Large, irregular brown saddle marks, which vary in appearance from individual to individual, run on the back. They have black edges and are separated from the basic color by a wide, light recess. On the flank side, the saddle spots partially have longitudinal connections to each other and thus enclose numerous large, extensive, light areas on the back. On the flanks, alternating with the back pattern, brown, rectangular spots with a lightened center run. In the back of the body, the flank spots become increasingly thinner and often merge with the saddle spots. In most animals, a long, light brown strip-shaped recess remains free between the dark pattern on the upper side of the tail. The ventral side is grayish to yellowish and has dark spots.

The head is drawn in high contrast. On the sides of the head of most animals, a light stripe runs diagonally backwards from below the nose to the second shield of the upper lip. Behind it, between the nose and the eye, there is a broad, dark spot. Then two white ribbons run below the eye to the upper lip and enclose a dark triangle in the middle. Behind the eye to the corner of the mouth there is a dark brown stripe that is typically wider than the diameter of the eye. The top of the head has an arrowhead-shaped, brown pattern that runs from the nose over the eyes to the nape of the neck and has a light point in the middle. The lower lip usually has dark spots. The rest of the underside of the head is white, only behind the throat do strong dark spots adjoin the underside of the neck. The black pupil is clearly visible in the brownish iris.

length

Northern rock pythons reach an average total length between 2.7 and 4.6 meters. This is confirmed by a study in southeast Nigeria, where the average head-to-torso length of 39 adult males averaged 2.47 meters. The 51 adult females examined were significantly larger with an average head-to-torso length of 4.15 meters. The largest of them was about five meters long. There is no reliable information on the maximum body length of this species. According to Villiers (1950), an individual with a total length of 9.8 meters is said to have been shot in Bingerville on the Ivory Coast in 1932 . According to Branch (1984) and Spawls et al. (2002) it is a dubious, implausible tradition. In addition, there are other unproven information about animals over 7 meters long. Massively overstretched hides were repeatedly held to be length records. In 1927 Loveridge measured a 9.1 meter long skin in East Africa. Although this skin was probably stretched by more than a quarter, it could originally have belonged to a northern rock python with a total length of over 6.5 meters. The longest northern rock python that has apparently been seriously measured to date comes from Uganda and, according to Pitman (1974), had a total length of 5.5 meters (18 ft).

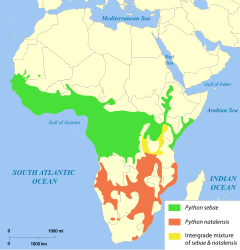

Distribution area

The distribution area of the Northern Rock Python extends south of the Sahara from the West African coast to the east over 6600 kilometers almost to the so-called horn of the east coast. In West Africa the species has been found in South Mauritania , Senegal , Gambia , Guinea-Bissau , Guinea , Sierra Leone , Liberia , the Ivory Coast , South Mali , Burkina Faso , Ghana , Togo , Benin , South Niger and Nigeria . In Central Africa, she is at home in southern Chad , Cameroon , the Central African Republic , Equatorial Guinea , Gabon , the Republic of the Congo , the Democratic Republic of the Congo and northern Angola . In the east, this python can be found in South Sudan , Ethiopia , Somalia , Kenya , Uganda , Rwanda , Burundi and Tanzania .

It is believed that the southern rock python once spread northward along the western and eastern valleys of the Great African Rift Valley in areas dominated by the northern rock python. In Kenya, 40 kilometers northwest of Mwingi , the areas of the two species still overlap . Relic populations are also present in Burundi and in the east of the Kivu Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In Tanzania there is an extensive overlap of the ranges of the two species to about 900 kilometers. In Angola, previous studies indicate a complete spatial separation of the two species.

habitat

The northern rock python inhabits a variety of different habitats in the tropics and subtropics , including mangrove forest , scrubland, permanently flooded swamp forest , secondary swamp forest, dense and loosened dry forest, grassland and sand plains. As a cultural follower, he often inhabits cassava , pineapple, sweet potato and oil palm plantations and fields. Quite often he also settles relatively inconspicuously in suburban settlements. A precondition for the settlement of all habitats is always proximity to water. He mostly lives in areas along permanent ponds, lakes, streams, rivers and sometimes brackish water . In southern Mauritania, however, it also lives in wetlands, where waters can dry out completely every year and then only patches of bank vegetation are available as retreats. Very humid areas are avoided by this snake. This species can hardly be found in the rainforest. In Rwanda, the species reaches altitudes of more than 1350 meters above sea level and in Uganda it has even been detected at 2250 meters above sea level. In Kenya and northern Tanzania, where the distribution of the northern and southern rock pythons overlap, the northern species is primarily present at lower altitudes.

behavior

The northern rock python is predominantly ground-dwelling and can move around here fairly quickly even as a large adult animal. As a good climber, he also regularly spends time in trees to hunt or avoid predators. In particular, young and subadult Northern Rock Pythons with a total length of less than 1.8 meters can often be found in trees and shrubs. Adult animals are considered to be less likely to climb. Adult pythons with a total length of over 2.5 meters are good swimmers and often spend long periods in the water. So far, there is no knowledge about the occurrence of young animals in water. On Lake Victoria , these pythons occasionally cover considerable distances, swimming freely between islands and the mainland. Furthermore, they are probably able to swim several kilometers even in the sea. This explains , for example, the occurrence on the coastal Chula Island of the Bajuni Islands in southern Somalia. In Uganda, the water is used especially during the hot days of the dry season to cool the body in the shallow water, only with the nostrils sticking out of the water surface. Rivers and streams are also used by this snake to enter populated areas in search of prey. The water is the starting point for looking for food and a protective hiding place when you retreat.

In areas such as southeast Nigeria, where the climate is subject to seasonal fluctuations, the species shows a variable activity pattern over the year. Activity maxima are observed during the dry season in January and during the last phase of the rainy season from August to September. In the equatorial countries of Kenya and Uganda, these pythons are described as predominantly crepuscular and nocturnal, although they are occasionally observed during the day while sunbathing or foraging. A more detailed investigation in the somewhat more northerly south-east Nigeria has shown that Northern Rock Pythons are mainly diurnal in areas remote from humans. Most of the animals are observed here in the afternoon between 3:00 p.m. and 5:30 p.m. In heavily forested areas, especially along streams and rivers, the species is most active from early morning to midday. In contrast, northern rock pythons near human settlements and urban areas are predominantly crepuscular and nocturnal with activity maxima during dusk.

During the inactive phases, this snake looks for hiding places in dense bushes, in bank vegetation, in the water, on trees, in crevices, in hollow tree trunks and abandoned caves of warthogs, aardvarks or porcupines. The python usually curls up in a ball, with its head resting on top.

So far, data on action areas and habitat changes have only been collected from one individual in southwest Cameroon. It was a female with a head-torso length of 2.4 meters and a mass of 3.7 kilograms, observed for a year by means of a tracking device. This animal moved primarily in a core area of 2.4 hectares , usually did not move further than 10 meters from bodies of water and changed frequently and repeatedly between several different habitats. It has been spotted in the forest, by and in the water, on farmland and in heavily populated areas, for example under an actively used wooden bridge.

nutrition

Juvenile Northern Rock Pythons often wander far and wide in search of prey and often climb trees to reach nests. With increasing size, the species tends to hunt more and more, with the prey often hiding on the edge of wild animal trails or well camouflaged on the banks of water. Like all giant snakes, the northern rock python then bites its prey and suffocates it by entwining itself.

The prey spectrum consists of a large number of different vertebrates, including mainly mammals and birds, to a small extent also reptiles and amphibians. The size of the prey correlates with the size of the python. A study in southern Nigeria has shown that pythons with a total length of less than 1.5 meters eat mice , redshank squirrels , sun squirrels and fruit bats in natural habitats . Gorse cats , monkey cats , giant hamster rats , cane rats and duikers have been detected in individuals under 2.5 meters . Animals with a total length of over 2.5 meters also preyed on the prey of the individuals under 2.5 meters in length, but also crocodiles and Nile monitors .

Furthermore, eating the way several species of frogs, various birds like African darters , cormorants , red-billed weaver , African Jacana , African dwarf ducks , Helmperlhühner , weaver birds , Felsenrebhühner , pelicans and Egyptian Geese and mammals such as spring hares , porcupines , representatives Real pigs , including young warthogs , Hussar monkeys , West African colobus monkeys and Ethiopian green monkeys . In areas with high mammalian populations, large northern rock pythons are also significant predators of antelopes, which in individuals with a total length of 4.5 meters can sometimes even weigh over 30 kilograms. These include Thomson's gazelles , young impala , bushbuck , sitatunga and reedbuck, as well as kobs and waterbuck fawns .

In inhabited areas of southern Nigeria, northern rock pythons with a total length of less than 2 meters prefer to feed on rats, while those over 2 meters primarily feed on chickens and individuals with a total length of over 3 meters rarely also on dogs and goats. Pythons that hunt in inhabited areas usually achieve a smaller maximum overall length than animals in pristine areas because of this prey offer.

Reproduction

Due to the large distribution area, the breeding time of the northern rock python is evidently subject to geographical variation. At the level of the equator around Lake Victoria , these pythons reproduce throughout the year due to the low seasonal climate fluctuations, while from the north-western countries of Cameroon and Gambia a mating season is reported that is limited to the cool winter months.

In the Gambia, groups of up to 6 animals have been observed that huddled close together during the day and crawled over each other. It was not possible to determine what kind of gender distribution it was. According to captivity observations, northern male rock pythons engage in commentary fights during this time, with the opponents lifting their heads, clasping each other's necks and trying to push the opponent to the ground. This can also lead to extensive wrapping of the body with squeezing and scratching with the aid of the anal spurs.

In captivity, the gestation period lasts between 30 and 120 days. In order to lay eggs, which correlates with the rainy season in Togo, for example, the female looks for a shady, protected hiding place near a body of water. Often abandoned mammalian caves, old termite mounds and deep crevices are used for this purpose. In the absence of such nesting sites, bushes, dense grass and piles of leaves are occasionally accepted.

The clutch size is strongly dependent on the size and constitution of the female and usually comprises between 30 and 50 whitish eggs. A clutch of 73 eggs is known from Cameroon, and a very large female in the London Zoo is said to have laid around 100 eggs in 1861. The clutches of eggs measuring an average of 90 × 60 millimeters and weighing around 150 grams are formed into a heap by the female, surrounded, protected from nest predators and only left sporadically to drink. The loop arrangement regulates moisture and heat. Whether northern rock pythons are capable of muscle tremors and thereby influence the incubation temperature is controversial. There are some indications that the species, unlike the southern rock python, is capable of this.

In Kenya the breeding season lasts around 60 days, in Uganda 90 days and in Togo 70 to 100 days are reported. Eggs that have been artificially incubated at a constant temperature of 28 to 32 ° C and a relative humidity of 90 to 100% take 50 to 75 days and those at lower temperatures up to 100 days to hatch. The hatchlings usually measure 50 to 65 centimeters, weigh 75 to 140 grams and are lighter and more clearly patterned than adults. In a clutch on Lake Tanganyika in Tanzania, the young remained for several days at the nesting site in an abandoned pangolin nest after hatching, while the mother left the nest a day later. In pairs or small groups, the young animals warmed themselves extensively in the sun no further than four meters from the cave. After the first molt after about six days, the first young animals then left the nest.

In captivity, sexual maturity is reached at three to five years and a total length between two and three meters. In southeast Nigeria, sexual maturity occurred when the average head-torso length was 1.70 meters.

Age and life expectancy

Information on the average and maximum ages of individuals living in the wild is unknown. Northern rock pythons regularly live to be 20 to 25 years old in captivity. In the San Diego Zoo a copy 27 years, 4 months and 20 days lived.

Danger

In some countries of its distribution area, the northern rock python is caught and processed for leather production. Certain tribes also use the species as a source of food. There is also, at least in Nigeria, a commercial trade in meat and an international trade in offal for traditional medicine. Live Northern Rock Pythons are also exported in small quantities. In Togo, for example, reptile farms have become established. Pregnant females from nature are captured here, housed in enclosures until they are laid and then released again. The eggs obtained in this way are artificially hatched and the hatched young animals are sold.

The increasing drought of the continually expanding Sahel zone is increasingly restricting the range of the northern rock python. In addition, there is the ongoing restructuring and destruction of habitats by humans. Due to the steadily growing oil industry of southern Nigeria, for example, the mangrove forests, which are preferred by the northern rock python, are exploited. Blasting, the construction of canals, roads and pipelines limit and destroy this habitat on an ongoing basis. Although this python is highly adaptable and can inhabit many human-altered areas, its population is declining in some countries.

The Northern Rock Python is listed as endangered in the Washington Convention on the Protection of Species in Appendix II and is therefore subject to trade restrictions.

Systematics

The northern rock python was given its scientific name Python sebae in honor of the German-Dutch natural history collector Albert Seba .

The relationships between the great African pythons: Python sebae ( Gmelin 1789), Python natalensis ( Smith 1840) and Python saxuloides (Miller & Smith 1979) were unexplained for a long time. There was a lack of specimen copies for the individual species, especially from places where they occur in sympatry or parapatry . Therefore, in the 20th century, these pythons were largely recognized only as a monotypic species and were listed under the name Python sebae . On the basis of a large collection of data, in 1984 Broadley differentiated rock pythons with northern and southern distribution areas, primarily on the basis of the fragmentation strength of the top shields and the pattern on the head side. Because of possible hybridizations in areas of overlap, he assigned the two groups only subspecies status and named the northern form Python sebae sebae and the southern form Python sebae natalensis . Python saxuloides turned out to be a slightly different Kenyan population from Python sebae natalensis and was equated with the latter. In 1999, Broadley assigned species status to the two subspecies, as new, more precise data from areas with extensive sympatry in Burundi, Kenya and Tanzania indicated no hybridization. In 2002, however, there were reports of mixed race near the Tanzanian city of Morogoro . Nevertheless, the division into two separate types is still applicable due to the current data situation. Further evidence of hybridization would have to follow or a genetic analysis would have to be negative in order to reverse the species status.

Among the real pythons , the northern and southern rock pythons are most closely related to the tiger python, which is native to South and Southeast Asia . This is the result of a recent molecular genetic study that includes the northern rock python and the tiger python.

Northern rock python and human

Behavior towards people

Wild Northern Rock Pythons avoid confrontation with humans. If a person gets too close to them, they usually try to escape into hiding or into the water. When disturbed, especially when cornered, certain animals quickly defend themselves and bite violently and repeatedly with their long front teeth, resulting in deep, infectious wounds. However, some individuals also let people come very close to them and only freeze or slowly crawl away. There are few reports that the northern rock python attacked and killed humans in the wild. However, there is no reliable evidence of this.

Cultural

Already in ancient times, attention was paid to the northern rock python. The ancient Greeks knew for several centuries BC Of giant snakes in Nubia , considered them typical of the fauna there and believed that some of them would even eat elephants. Ptolemy II , who lived from 282 to 246 BC. BC was the second Ptolemaic king of Egypt , commissioned a group of around 100 men of hunters, riders, slingshots , trumpeters and archers to catch one of the largest of these snakes and bring it alive to his widely famous menagerie . In southern Nubia, where the northern rock python was still widespread at that time, the men are said to have succeeded after several attempts to catch an extremely well-fortified individual with a total length of supposedly over 13 meters and bring it to the king. This "beast" was then fed and tamed in the menagerie and was considered Ptolemy II's most extraordinary and famous animal. The northern rock python was also repeatedly the subject in mosaics . In the Nile mosaic of Palestrina , which dates from around 200 BC BC, a large python, which is winding around a rock, and a second, which is just preying a bird on the banks of the Nile , are shown. Another mosaic from the former Roman Carthage , made between the second and fourth centuries AD, shows a python fighting an elephant.

In the ancient Roman Empire , snakes were often displayed during circus games. The partially tamed northern rock pythons were also considered attractive.

In some West African cultures there was a cult of snakes before colonization . In particular, the northern rock python and the ball python were considered sacred, kept in snake temples and venerated. In ceremonies, the northern rock python was given numerous gifts and satisfied with the sacrifice of a chicken or lamb. This python was so important in Nigeria, for example, that one of the first contracts between English invaders and tribal leaders regulated the protection of these snakes. To this day, this species is idolized in many parts of its range. In South Sudan, for example, the Dinka , Shilluk and Bari people believe that certain individual animals are carriers of the souls of the deceased. These pythons enjoy the utmost respect there, are given offerings and prayers are made to them to avert misery, disease, drought and famine. There is a widespread belief in some local societies that after killing a Northern Rock Python, rain will stop falling. Some groups, including those who only idolize individuals, kill Northern Rock Pythons for food and traditional medicine. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example, they are hunted with spears or caught with snare traps at the entrance to their hiding places. The meat is said to be tasty, similar to cod , and python fat is said to have miraculous healing properties for curing numerous diseases.

swell

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n B. Lanza, A. Nistri: Somali Boidae (genus Eryx Daudin 1803) and Pythonidae (genus Python Daudin 1803) (Reptilia Serpentes) . Tropical Zoology 18, 2005, pp. 67-136, online, pdf .

- ↑ a b c d e f J. G. Walls: The Living Pythons . TFH Publications, 1998, ISBN 0-7938-0467-1 , pp. 142-146, 166-171.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i D. G. Broadley: A review of geographical variation in the African Python, Python sebae (Gemelin) . British Journal of Herpetology 6, 1984, pp 359-367.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t C. RS Pitman: A guide to the snakes of Uganda . Codicote Wheldon & Wesley, Ltd, 1974, ISBN 0-85486-020-7 , pp. 67-71.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j L. Luiselli, G. C Akani, EA Eniang, E. Politano: Comparative ecology and ecological modeling of sympatric Pythons, Python regius and Python sebae . In: RW Henderson and R. Powell (Eds.): Biology of the Boas and Pythons . Eagle Mountain Publishing Company, Eagle Mountain 2007, ISBN 978-0-9720154-3-1 , pp. 89-100.

- ^ A. Villiers: Les serpents de l'ouest africain . Institut Français d'Afrique Noire, Dakar 1950. Quoted in: B. Lanza, A. Nistri: Somali Boidae (genus Eryx Daudin 1803) and Pythonidae (genus Python Daudin 1803) (Reptilia Serpentes) . Tropical Zoology 18, 2005, p. 103.

- ^ A b W. R. Branch: Pythons and people: predators and prey . African Wildlife 38, No. 8, 1984, pp. 236-237, 240-241. Quoted in: B. Lanza, A. Nistri: Somali Boidae (genus Eryx Daudin 1803) and Pythonidae (genus Python Daudin 1803) (Reptilia Serpentes) . Tropical Zoology 18, 2005, p. 103.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l S. Spawls, K. Howell, R. Drewes, J. Ashe: A Field Guide to the Reptiles of East Africa . Academic Press 2002, pp. 305-310, ISBN 0-12-656470-1 .

- ^ A. Loveridge: Blind snakes and pythons of East Africa . Bulletin of the Antivenine Institute of America 3, 1929, pp. 14-19. Quoted in: WR Branch, WD Haacke: A Fatal Attack on a Young Boy by an African Rock Python Python sebae . Journal of Herpetology 14, No. 3, 1980, p. 306.

- ^ WR Branch, WD Haacke: A Fatal Attack on a Young Boy by an African Rock Python Python sebae . Journal of Herpetology 14, No. 3, 1980, pp. 305-307.

- ↑ a b J. M. Padial: On the presence of Python sebae Gmelin, 1788 (Ophidia: Pythonidae) in Mauritania . Herpetological Bulletin 84, pp. 30-31, 2003.

- ↑ a b c D. G. Broadley: The Southern African Python, Python natalensis A. Smith 1840, is a valid species . African Herpetological News 29, 1999, pp. 31-32.

- ↑ a b c D. P. Lawson: Python sebae (African Rock Python). Habitat use and home range . Herpetological Review 35, No. 2, 2004, pp. 180-181.

- ↑ a b c L. Luiselli, FM Angelici, GC Akani: Food habits of Python sebae in suburban and natural habitats . East African Wild Life Society, African Journal of Ecology 39, 2001, pp. 116-118.

- ^ A b c d M. Harris: Assessment of the Status of Seven Reptile Species in TOGO . Report to the Commission of the European Union, 2001, online, pdf

- ^ PL Sclater: Notes on the Incubation of Python sebae, as observed in the Society's Gardens . Proceedings of the scientific meetings of the Zoological Society of London 1862, pp. 365-368.

- ↑ a b c G. J. Alexander: Thermal Biology of the Southern African Python (Python natalensis): Does temperature limit its distribution? In: RW Henderson, R. Powell: Biology of the Boas and Pythons . Eagle Mountain Publishing Company, Eagle Mountain 2007, ISBN 978-0-9720154-3-1 , pp. 51-75.

- ↑ CB Stanford: Python sebae (African Rock Python). Reproduction . Herpetological Review 25, No. 3, 1994, p. 125.

- ↑ CITES: Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora : Appendices I, II and II, valid from July 1, 2008, online .

- ^ TJ Miller, HM Smith: The Lesser African Rock Python . Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 15, No. 3, 1979, pp. 70-84. Quoted in: GJ Alexander: Thermal Biology of the Southern African Python (Python natalensis): Does temperature limit its distribution? In: RW Henderson, R. Powell: Biology of the Boas and Pythons . Eagle Mountain Publishing Company, Eagle Mountain 2007, ISBN 978-0-9720154-3-1 , pp. 51-75.

- ↑ LH Rawlings, DL Rabosky, SC Donnellan, MN Hutchinson: Python phylogenetics: inference from morphology and mitochondrial DNA . Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 93, 2008, pp. 603-619, [cteg.berkeley.edu/~rabosky/Publications_files/Rawlings_etal_BJLS_2008.pdf online, pdf].

- ^ L. Bodson: A Python, Python sebae (Gmelin, 1789), for the King: The Third Century BC Herpetological Expedition to Aithiopia . Bonn zoological contributions 52, issue 3, 2004, pp. 181–191, online, pdf

- ^ A b Wolf-Eberhard Engelmann, Fritz Jürgen Obst : With a forked tongue - biology and cultural history of the snake ; Herder Verlag 1981, ISBN 3-451-19393-0 , pp. 57, 116, 214.

- ^ A b F. W. FitzSimons: Pythons and their ways . George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd, London 1930, pp. 137-139.

literature

- DG Broadley: A review of geographical variation in the African Python, Python sebae (Gemelin) . British Journal of Herpetology 6, 1984, pp 359-367.

- Benedetto Lanza , Annamaria Nistri : Somali Boidae (genus Eryx Daudin 1803) and Pythonidae (genus Python Daudin 1803) (Reptilia Serpentes) . Tropical Zoology 18, 2005, pp. 67-136, online, pdf .

- L. Luiselli, FM Angelici, GC Akani: Food habits of Python sebae in suburban and natural habitats . East African Wild Life Society, African Journal of Ecology 39, 2001, pp. 116-118.

- L. Luiselli, G. C Akani, EA Eniang, E. Politano: Comparative ecology and ecological modeling of sympatric Pythons, Python regius and Python sebae . In: RW Henderson, R. Powell (Eds.): Biology of the Boas and Pythons . Eagle Mountain Publishing Company, Eagle Mountain 2007, ISBN 978-0-9720154-3-1 , pp. 89-100.

- CRS Pitman: A guide to the snakes of Uganda . Codicote Wheldon & Wesley, Ltd, 1974, ISBN 0-85486-020-7 , pp. 67-71.

- S. Spawls, K. Howell, R. Drewes, J. Ashe: A Field Guide to the Reptiles of East Africa . Academic Press 2002, ISBN 0-12-656470-1 , pp. 305-310.