Pero Tafur

Pero Tafur (* around 1410 in Córdoba ; † before 1490) was an early Castilian travelogue. He was already a confidante of King Juan II before 1435. In his service he undertook a journey from 1435 to 1439, during which he got to know the entire Mediterranean and Black Sea region , but also parts of Central Europe. On the Sinai he met the Venetian merchant and explorer Niccolo di Conti . He traveled to Italy , then via Palestine and Egypt to Constantinople . From there he traveled around the Black Sea, to Greece , again to Italy, and finally to the countries north of the Alps . He returned to Spain via Italy. Apparently he carried numerous recommendations with him, because the trip, which he said he was going on on his own, brought him into contact with high-ranking personalities. He justified his trip with wanting to see some parts of the world, so you could call it a private educational trip . On his return he married (before 1452) Doña Juana de Horozco. She gave birth to a son who died before his father and three daughters. He and his son were councilors in 1479.

origin

Tafur was a descendant of Pedro Ruiz Tafur , who led the troops of the Castilian king to victory over the Moors near Córdoba. His father was Juan Díaz Tafur, a nobleman who was born in Cordoba.

Itinerary

In 1435 Pero Tafur embarked with at least two squires in San Lucar de Barrameda . First he supported his master Don Enrique de Guzman, Count of Niebla , in his unsuccessful attack on the Muslim Gibraltar . Enrique was killed and Pero Tafur led his troops back to San Lucar. He sailed to Genoa in a convoy of three vessels , visited Ceuta and the Muslim city of Malaga . After a heavy storm in the Golfe du Lion , his ship reached Nice at Christmas 1435, while the other two ships drifted far out. When he tried to draw his bills of exchange in Genoa, the traders there refused to accept them. He got into an argument, but was able to take action against the traders through influential friends. At the end of December he witnessed the uprising against the Duke of Milan, with the help of the condottiere Niccolo Piccinino he got on a ship in Portovenere , which enabled him to continue his journey via Pisa and Florence to Bologna .

Here he met the exiled Pope Eugene IV , who blessed him. Although he got to Venice, there was no pilgrimage to the Holy Land , so he visited other parts of Italy while waiting. He spent Lent in Rome. From there he traveled to Viterbo , Perugia and Assisi . Through a trick he obtained the support of the pious Guid 'Antonio da Montefeltro in Gubbio , who made the pilgrimage to the east possible for him, which he started on the Ascension of Christ in 1436.

In Jerusalem he visited numerous pilgrimage sites, traveled to Bethlehem , then via Jericho to the Jordan and the Dead Sea . In Jerusalem, disguised as a Muslim, he entered the Omar Mosque in violation of the prohibition . Then he wanted to go to St. Catherine's Monastery on Sinai, but a caravan had just left, so he was advised to sail to Cairo via Cyprus . In Damiette he was suspected of espionage, but was able to escape. But now he had to hide his identity from time to time. He described the behavior of the crocodile (“cocatriz”) from his own experience, but he only knew the hippopotamus from hearsay.

In Cairo, he made friends with the Sultan's chief translator, a Jew who had fled from Seville . Tafur claimed to come from there as well. Through him, his very generous host, he received an audience with the Sultan. After visiting the pyramids, he traveled on towards Sinai, a 15-day journey under the most difficult conditions. Tafur consulted with the prior as he planned to travel on to India. He advised him to wait for the arrival of a caravan with which Nicolo de 'Conti was traveling. When he met him he claimed to be Italian. It was only when de 'Conti remained skeptical that he confessed his true origin. The Italian urgently advised the Castilian against the trip and reported on his own undertakings. Tafur traveled on to Alexandria to return to Cyprus soon. He tolerated the climate better than the desert heat, so that in view of the friendly reception he was inclined to take on an office there.

But Tafur traveled on to Rhodes , where pirates attacked his ship and sank the escort boat. The crew drowned, Tafur's ship escaped in the dark. In Rhodes he witnessed the election of the successor to the late master of the order, which he described in detail. In front of Chios his life was in danger again when he was shipwrecked and drifted for days clinging to a piece of wood on the sea. But he traveled on to Troy , then to Constantinople, which he reached in November 1437.

Emperor John VIII Palaiologos received him, but he was not particularly interested in the alleged descent of his guest from the eastern emperors. Instead, the emperor suggested that he accompany him on his trip to Western Europe in order to perhaps save Constantinople from the Turks. Tafur preferred to visit Sultan Murad II himself. Tafur describes the Ottoman as a serious, friendly man aged 40 to 45. He traveled east to Trebizond , where he was received by the local emperor John IV Comnenus . The strict Castilian did not like that the emperor had married a non-Christian woman, but above all that he had overthrown and murdered his own father. So he traveled on to Kaffa in the Crimea. The great city, which far overshadowed Seville, was dominated by Genoese who were more familiar with its beliefs. They profited from long-distance trade between Europe, Africa and Asia. At the slave market he bought two girls and a man whom he took to Castile. Tafur also visited the headquarters of the great khan, probably considering the idea of continuing to Tartary , but he followed the advice to return to Constantinople, even if the city was very impoverished and depopulated. After an extensive visit to the city, he sailed for Venice. During the passage through the Dardanelles he persuaded the captain to free some Christian slaves, but the men got into fights in which Tafur was injured. This wound only seems to have healed during the onward journey to Basel . At first he almost drowned, but he now safely reached the Venice lagoon on Ascension Day 1438.

In Venice he got into a dispute with the customs authorities, who had confiscated his goods and slaves, but he met Spanish pilgrims who helped to solve the problem. In the city he witnessed the Doge's solemn marriage to the sea , admired the state structure and the gondolas . In contrast to Constantinople, Tafur described the city as clean, so that there was no mud in the winter and no dust in the streets in summer, the paths were clad, and the houses were adorned with good brickwork. Although the hygienic conditions were bad here too, the people always carried fragrant spices and herbs with them. He also visited the arsenal , where he witnessed the construction of ships, a work that was already highly organized. Tafur's description of the city is one of the most important sources for everyday life in Venice in the first half of the 15th century.

He left his property in Venice and traveled to Ferrara , where he met the Pope and the Byzantine emperor, who, however, suffered from a severe gout attack . Tafur removed his beard, attended council meetings, traveled to Milan . He even claimed that he had spoken to Filippo Maria Visconti , who never received a foreigner. Then he traveled over the Gotthard Pass to Basel , where his injury finally healed. Then he drove down the Rhine , a passage he declared to be the most beautiful river in the world. Archbishop Dietrich II von Moers received him in Cologne . He showed him the city and introduced him to the most important men. Now he traveled to Mechelen and Brussels , where he was received by Duke Philip the Good . He also visited Ghent and Antwerp . His descriptions of Sluys and Bruges are as important as those of Venice.

As Tafur with some prelates to the Council of Basel wanted to travel, the men were at Mainz captured by a nobleman fourteen days. But Tafur managed to get into conversation with the kidnappers. When one of the servants was supposed to return his sword to him, however, there was a scandal because the sword could not be found. Tafur now threatened that a Castilian army would devastate the whole country, which was enough to bring the sword to light again.

Tafur now traveled to Prague to pay his respects to the Roman-German emperor, but he was in Breslau , where he followed him. The travelers arrived there at Christmas 1438. Albrecht II tried to persuade the Castilian to stay, but he preferred to go to Vienna in the company of a group of knights , whereupon he was extremely cold. Shortly before Vienna he separated from his companions, but was attacked almost immediately by a nobleman, and only the swift horses ensured that he escaped with his three slaves. In an inn where the leader of the robbers happened to be staying the night, he confronted him. He apologized for his robbery, but explained that as an impoverished nobleman, he had no choice but to earn a living. They even offered to rob someone else to help Tafur, who was also a poor nobleman. In Vienna he met Elisabeth, the daughter of Emperor Sigismund . From Vienna he traveled to Buda and Neustadt, where he met the future Emperor Friedrich III. met.

Tafur traveled across the Carnic Alps to Ferrara , where the Pope and the Byzantine emperor were just about to leave for Florence . He continued his journey to Venice, where he witnessed how 25 barges and 6 galleys were towed across the Tyrolean Alps to Lake Garda. After a brief visit to Florence, he sailed home. In March or April 1439 he was back in Castile.

Marriage and children

In 1452 at the latest he married Doña Juana de Horozco, with whom he had three children, namely a boy named Juan, and three girls named Elena, María and Mayor.

memories

He is said to have written down his memories of his travels from 1435 to 1439 between 1453 and 1457; he dedicated it to Don Fernando de Guzman, General of the Calatrava Order . The fact that he mentions the uprising of Ghent against Duke Philip of Burgundy in 1452/53 indicates this date of origin .

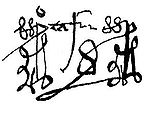

His work was first printed in Spanish in 1874; an English edition appeared in 1926 in the series The Broadway Travelers . The Spanish edition was based on the only surviving manuscript that was in the Colegio mayor de S. Bartolomé de Cuenca in Salamanca , later in the Biblioteca Patrimonial. However, it was a copy, probably of the autograph , from the early 18th century. This copy includes 911/12 folia , which apparently took over the language style, but also the spelling and punctuation of the 15th century. She also marks missing words or lines with three dots. Apparently the last page was missing because the narrative breaks off abruptly.

Works

- Hakan Kılınç: Pero Tafur Seyahatnamesi , Kitap Yayınevi, İstanbul 2016.

- Pedro Martínez García. El cara a cara con el otro la visión de lo ajeno a fines de la Edad Media y comienzos de la Edad Moderna a través del viaje , Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang 2015.

- Marcos Jimenez de la Espada (ed.): Andanças e viajes de Pero Tafur por diversas partes del mundo ávidas (1435-1439) . Ginesta, Madrid 1874. ( online )

- E. Denison Ross, Eileen Power (Ed.): Pero Tafur Travels and Adventures 1435-1439 . Routledge 1926 ( The Broadway Travelers ) ( online )

literature

- Mike Burkhardt: Strangers in late medieval Germany - the travel reports of an unknown Russian, the Castilian Pero Tafur and the Venetian Andrea de 'Franceschi in comparison. In: Concilium Medii Aevi 6 (2003), pp. 239-290. ( PDF )

Web links

- Mike Burkhardt: Strangers in Late Medieval Germany (with biography and additional literature) (PDF file; 259 kB)

- E. Denison Ross, Eileen Power (Ed.): Pero Tafur Travels and Adventures 1435-1439, Routledge, London 1926 ( Memento of May 14, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

Remarks

- ↑ Juan Ruiz: Pero Tafur , in: Archivo Biografico de España, Portugal e Iberoamerica. Nueva Serie, Munich 1986, pp. 306–326, here: p. 312. His wife's will is dated to 1490 ().

- ↑ Mike Burkhardt: Strangers in Late Medieval Germany - The travel reports of an unknown Russian, the Castilian Pero Tafur and the Venetian Andrea de 'Franceschi in comparison , in: Concilium medii aevi 6 (2003) 239-290, here: pp. 245f.

- ↑ Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Vasilʹev: Pero Tafur: A Spanish Traveler of the Fifteenth Century and his Visit to Constantinople, Trebizond, and Italy , in: Byzantion 7 (1932) 75-122, here: p. 78.

- ^ Antonio Ballesteros y Beretta: Historia de América y de los pueblos americanos , Salvat, Barcelona 1938, p. 475.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tafur, Pero |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish travel reporter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1410 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cordoba |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 1484 |