Battle for Guadalcanal

| date | August 7, 1942 to February 9, 1943 |

|---|---|

| place | Guadalcanal , Solomon Islands |

| output | American victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Robert L. Ghormley USN |

Hyakutake Haruyoshi |

| Troop strength | |

| approx. 75,000 soldiers and seamen 3 battleships 4 aircraft carriers 16 cruisers 39 destroyer transport ships |

approx. 50,000 soldiers and seamen 2 battleships 5 aircraft carriers 11 cruisers 29 destroyer transport ships |

| losses | |

|

2 aircraft carriers |

2 battleships |

The Battle of Guadalcanal was one of the turning points of World War II in the Pacific theater . The American code name was Operation Watchtower . For the first time, US forces went on the offensive against Japan , which had occupied much of the western Pacific since December 1941 . From August 1942 to February 1943, the island of Guadalcanal was the focus of very fierce fighting on land, sea and in the air. The supply routes to Guadalcanal were also fiercely contested. Both sides lost aircraft carriers , several cruisers and numerous smaller ships. In the course of the conflict over Guadalcanal around 50 ships on both sides were sunk by air raids and in sea battles , so that the waters around Lunga were given the name Ironbottom Sound (Eisengrundsund). On the American side, at the end of the conflict, the number of sailors killed at sea exceeded the number of soldiers killed in months of tough jungle fighting.

In the numerous aerial battles, Japan also lost most of its remaining pilots trained before the war. Their replacement, withdrawn from schools prematurely, fell out quicker and had to be replaced in turn. The flying level of the Japanese pilots has steadily declined since then and ultimately led to the kamikaze , the only remaining means of resistance.

prehistory

As early as the beginning of May 1942, the Japanese armed forces managed to establish a base on the island of Tulagi , north of Guadalcanal, as part of Operation MO . In early summer the Japanese expanded their territory to include Guadalcanal itself and began to build a small air force base near Honiara , called Lunga Point , after the river delta of the same name in the vicinity. With this airfield, the Japanese would have gained control of the southern Solomon Islands . The Australian supply routes and New Guinea could be reached from here.

As the US High Command (JCS: Joint Chiefs of Staff ) became known in the early summer of 1942 that the Japanese on Guadalcanal built an airfield, it decided, at the instigation of Admiral Ernest King , the commander in chief of the US Navy that the counter-offensive Allies in Guadalcanal should begin. The island gained by establishing a airfield strategic importance as Japanese long-range bombers of the type Mitsubishi G4M would have been able by sea between the United States and Australia attack.

landing

Guadalcanal

The American landing

On the night of August 7, 1942, Task Force 61 under Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher brought about 19,000 American marines into position to attack and occupy the island of Guadalcanal and the smaller Tulagi, a little to the north.

The landing fleet, Task Group 61.2, consisting of 13 large troop transports , six large supply units and four smaller transport destroyers , was accompanied by eight cruisers , including three Australian destroyers, 15 destroyers and five fast minesweepers . This force was led by Rear Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner .

Further out at sea was Task Group 61.1, which comprised three aircraft carriers USS Saratoga , USS Enterprise and USS Wasp , with a total of around 250 aircraft, as well as the battleship USS North Carolina , six cruisers, 16 destroyers and five supply tankers. They were all under the command of Rear Adm . Leigh Noyes .

The long Battle of Guadalcanal began shortly after 6 a.m. with the heavy cruiser Quincy bombarding Japanese positions near Lunga Point .

The 1st Marine Division of the US Marines under Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift landed at about 9 a.m. on Red Beach , a small, gray-sand beach near the Tenaru River. Because of their numerical superiority, the Marines encountered little resistance here. The Japanese defenders suffered heavy losses and had little success. On August 9, most of the 19,000 Marines were brought ashore.

On the afternoon of the following day, the Americans were in possession of the almost completed airfield . The surviving Japanese units had withdrawn far into the interior of the island and left a lot of valuable equipment to the conquerors, which in the following years would prove to be very useful for the new owners.

A typical approach for landing operations at the time was the haphazard approach of supplies . The unloading of the ships took place so quickly that after a relatively short time the beaches around Lunga Point were full of material that could not be transported inland quickly enough. Japanese air strikes hardly interfered with this endeavor. But when the transport ships withdrew on August 9, not one of them had been completely unloaded. As a result, supply bottlenecks occurred over the next few weeks when the Japanese attempted to recapture the strategically important airfield with air and sea attacks.

Likewise, not all supplies and soldiers could be brought ashore, since Admiral Fletcher did not want to lead a sea battle with inferior forces and therefore left his fleet only two days near the landing zone. Vandergrift had the transport fleet retreat one day later.

Japanese counterattacks

The Japanese reaction to the landing was quick but unsuccessful. In Rabaul , the nearest Japanese base, Vice Admiral Mikawa Gunichi assembled a small auxiliary force and shipped them to Guadalcanal. One of the transporters was sunk by the American submarine S-38 during the night . 300 men died and the troop transport turned back.

Meanwhile, Japanese planes took off from Rabaul in search of the American aircraft carriers. Since they could not find them, they appeared over the invasion fleet in the early afternoon of August 7th. 27 bombers and some Zero fighter planes bombed the landing forces and ships from great heights. All machines were lost to American fighter planes launched by the porters, or they landed on the way back. They had done almost no damage.

The Japanese plane attacks continued the next day. The Japanese again attacked the landing fleet with torpedoes. The ships were meanwhile relatively well protected in a sound . A torpedo hit a destroyer in the bow and a falling bomber hit a transport ship, which sank as a result. The Japanese Air Force lost half of the machines used by anti-aircraft fire from the ships.

Tulagi, Gavutu and Tanambogo

At around 8 o'clock, allied marines landed in the southwest of the small island of Tulagi north of Guadalcanal. They formed a front line across the small island and tried to push the Japanese to the east. A light cruiser and two destroyers fired at the Japanese with their artillery. The 500 Japanese stationed on the island also belonged to a marine infantry unit . On the evening of August 7th, the Americans had pushed the decimated Japanese back to the northeast of the island. During the night the Japanese made some attempts to escape, but when American reinforcements came in from Guadalcanal, the island was quickly taken. It was a few days before the last Japanese defenders could be defeated. The fighting took the lives of 45 American Marines and almost all of the Japanese.

Tulagi was set up in support of the fighting on Guadalcanal as a port of refuge for damaged ships and a base for seaplanes and torpedo boats .

The two islands of Gavutu and Tanambogo a few miles to the east were as fiercely contested as Tulagi. There the Japanese maintained a seaplane station that the Australians captured in May. After all the machines had been destroyed by American carrier aircraft, the only option left for the pilots, the ground crew and some marines was to continue fighting as infantrymen.

Both islands were bombed before landing, but the Japanese were still able to offer considerable resistance on Gavutu. The fighting continued throughout the day and the following night. Only after reinforcements arrived for the Americans on the morning of August 8, the island could be taken.

The attack on Tanambogo on the afternoon of August 7th was a failure, so the island was still in Japanese hands the next day. Heavy bombing of Navy ships then enabled the Americans to take the island. But just like on Tulagi, it took days for a few Japanese to break the fighting spirit. 70 Marines lost their lives and only a few Japanese were captured.

Further process

The airfield at Lunga, captured on August 8 by the American Marines, was named Henderson Field shortly afterwards in honor of a naval pilot who died in the Battle of Midway . On August 12, the first aircraft was able to use the repaired runway. The first Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters and Douglas SBD Dauntless dive fighters of the Marines followed on August 23 .

“The Battle of Guadalcanal raged around this Henderson Field for half a year. All conceivable combat operations on land, sea and in the air were fought out here with bitterness, raging on the island, above it, all around. The history of the struggles between people knows enough examples of bloody battles for any place, for some Austerlitz or Douaumont, names that suddenly emerge from anonymity and soon revert to their old insignificance as soon as the last victim is buried. But even more insignificant and unknown were those few square meters of Henderson Field, a piece of rotting earth on an island full of horror that has long since fallen into the wilderness again. ( Raymond Cartier ) "

(Henderson Field did not succumb to the wilderness; it has become Honiara International Commercial Airport.)

Major General Alexander Archer Vandegrift commanded the 1st Marine Division in the extremely tough and bloody ground fighting around Guadalcanal. The battle for Guadalcanal was described as " fighting in a confined space ".

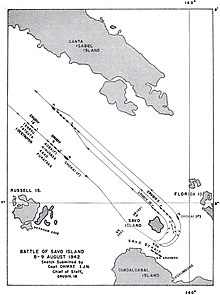

Naval Battle of Savo Island (August 8/9, 1942)

On the evening of August 8, Admiral Fletcher, concerned about his own previous aircraft losses and possible Japanese attacks using land-based aircraft, withdrew his carrier group from the Solomon Islands. The failure of the air support forced Turner to cancel the unloading of supplies and also to withdraw. Turner planned to take advantage of the night and pull out his vans on August 9th.

In the meantime, Mikawa had planned a counterstrike and the 6th Cruiser Division under Rear Admiral Gotō Aritomo, stationed in Kavieng , had pulled together with the ships of the 8th Fleet available to him in Rabaul. On the evening of August 7, Goto's four heavy cruisers met with Mikawa's three cruisers and a destroyer at Cape St. George and set off for Guadalcanal. Driving around Bougainville to the north, where they were spotted by an American submarine and Australian reconnaissance aircraft, they passed the so-called Slot , the strait of the sea between the Solomon Islands, on the afternoon of August 8th . Mikawa had previously had his reconnaissance planes clear up the situation near Guadalcanal and located two American groups of ships near Guadalcanal and Tulagi, which he planned to attack one after the other that night.

The commander of the Allied Cover Group Task Force 62.2, Rear Admiral Victor Crutchley , had divided his forces into three groups: a southern group of three cruisers and two destroyers between Lunga Point and Savo Island , an equally strong northern group between Florida Island and Savo Island and an eastern group from two cruisers and two destroyers between Florida Island and Guadalcanal. Two radar-equipped destroyers patrolled west and north of Savo Island, and seven other destroyers were split between the two landing points as close-range support. Crutchley himself attended a conference called by Turner that evening and was unable to take command at the critical time.

Despite American precautions, Mikawa managed to invade the sound undetected. At around 1:45 a.m. his ships opened fire and severely damaged two cruisers from the southern group. Then they turned to the north and attacked the northern group, sinking two cruisers and seriously damaging one. Although Mikawa was urged by some members of his staff to attack the anchored transport ships, he decided to retreat around 2:20 a.m., for various reasons such as the risk of a fight with the American carriers and the high ammunition consumption. Although he was later criticized for this decision, he had achieved a convincing victory. A total of four Allied heavy cruisers were sunk and one badly damaged, while the Japanese lost one heavy cruiser on the return march to an American submarine and otherwise had only minor damage.

The battle of Savo Island and the withdrawal of the American porters meant that the Marines on Guadalcanal were left with insufficient supplies. The Americans became overly cautious and in the following time only carried out supply trips during the day and with strong air support, which did not improve the supply situation.

Battle of Tenaru (August 21, 1942)

On August 21, the 28th Japanese Infantry Regiment advanced on the Tenaru coastal strip against the American marines who had dug in between the Lunga and Tenaru rivers. Locals warned the Americans so they could prepare for the attack. Many Japanese had already fallen when the US 1st Marine Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Lenard B. Creswell counterattacked and trapped the attackers. 15 Japanese surrendered, 800 fell. Colonel Ichiki Kiyonao took his own life in the seppuku ritual .

The following fighting went ahead: Colonel Ichiki led an elite unit which had already gained combat experience in China and which underestimated the Americans in terms of both morale and troop strength. Ichiki reckoned with 2000 US soldiers, in fact there were already 15,000 marines on the island.

He initially put 900 of his 2100 soldiers who had already landed on standby and did not consider it necessary to wait for the remaining 1200 soldiers in his regiment, whose ships had not yet arrived at Guadalcanal.

American fighting strength was judged to be extremely weak and insignificant.

Ichiki's soldiers were spiritual warriors who acted according to the Bushidō Code and were believed to have supernatural powers.

To the west of the Tenaru River, the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Marine Division dug into the fence. Scouts reported a larger deployment of the Japanese, as large troop movements were observed from the east.

Some US patrols were already in contact with the enemy and engaged in minor firefights with the approaching Japanese.

The Tenaru River fans out together with the Lunga and Ilu Rivers and the river known by the locals as " Alligator Creek " to form a confusing delta landscape with meandering river arms, tidal lagoons and sand dunes.

The first of a total of four waves of Japanese attack attacked the expanded US positions at 01:30 a.m. with about 100 soldiers with their side guns attached. Ichiki's "shock troop regiment " was prepared for such operations through intensive hand-to-hand combat training. The first group got stuck in the barbed wire barrage of the Americans and overcame the obstacle with Bangalore detonators, but were held down by machine guns and 37 mm cannons.

On the broken line, bitter close-range fighting developed. Some American outposts could be overwhelmed.

From the east side of the river, Japanese machine guns successfully fought US machine gun nests and thus threatened their flanks for some time.

A reserve company of marines was able to push back the broken-in Japanese shock troops. A second stronger wave of around 150 to 200 soldiers, which advanced at 2:30 a.m., was also repulsed. Japanese officers asked Ichiki for an orderly retreat, but this was strictly refused.

Lieutenant Colonel Edwin A. Pollock, commander of the 2nd Battalion, reported on a large number of Japanese dead who were literally piled up on the dune area.

While the US Marines recorded 34 dead and 75 wounded, the Japanese probably had more than 700.

While the Japanese attackers rearranged themselves, they smeared the American positions with heavy mortar fire, which was answered with artillery counter attacks from grenade launchers and 75-mm field guns on the eastern disposal areas of the Japanese army.

The last wave of Japanese attacks started around 5:00 a.m., with soldiers wading through the surf and attempting to take the western bank of the river from the beach side. Here Ichiki suffered what is probably the heaviest loss of his operation.

In the next few hours, confusing firefights developed at the shortest possible distance, which were conducted with mutual success. Despite heavy losses, Ichiki's soldiers were able to hold the eastern bank of the river. Lieutenant Colonel Cresswell decided to counterattack from the south and east across the " Alligator Creek " to take advantage of the weak phase of the Japanese and to enclose them in a limited space. Fighter planes taking off from Henderson Field prevented the Japanese from retreating, and five M3 Stuart tanks were sent into the coconut forest to destroy the Japanese there. Vandegrift later wrote that "the back of the tanks looked like a meat grinder" because the Japanese could not or would not evade.

The Japanese resistance ended at around 5:00 p.m. Nevertheless, US patrols that combed the battle area were still partially shot at by wounded opponents, for this reason all the Japanese lying on the ground were either shot or bayonet stabbed. Only 15 wounded or fainted Japanese could be captured. The Tenaru River victory had a powerful psychological impact on US war morale, as it was proven that the Japanese army could also be defeated in a land battle.

Based on the experience of the Battle of the Tenaru River, the US doctrine on the treatment of the Japanese wounded, who from then on were often killed for safety reasons, changed.

Japanese wounded, who were to be treated by US medics, sometimes detonated a hand grenade when the enemy was close enough.

“The next morning, bodies were lying around everywhere. They had a rule, the Japanese, which was worse than the one we had to fight to the death. When they found they were losing, they put a hand grenade against their head or stomach. We saw all these bodies in this goddamn place. We went and got tractors and drove over the dead bodies first before doing anything else. We had to do that, they were lying on their stomachs and had a hand grenade or something like that. "

Around 45 marines killed in action were compared to around 700 fallen Japanese soldiers. Admiral Tanaka Raizō stressed that the tragedy of the Tenaru River shows the futility of the Japanese bamboo spear tactics.

Cartier describes the Japanese attack on the Tenaru coastline:

“But a native scout had betrayed the approach of the Japanese regiment. Some Japanese soldiers killed in an ambush were also found too well fed to be among the troops already present here. So the attack came upon the well-prepared Americans, who soon saw the swamp of the Delta littered with the corpses of their enemies. The first battalion of the 1st Marine Infantry Regiment, under Lieutenant Colonel Crestwell, counterattacked and trapped the attackers in a coconut forest. For the first time the Japanese found themselves facing an opponent who was still able to teach them a lesson in fighting spirit and aggressive spirit. The light American tanks drove against the flexible trunks of the coconut trees until snipers and frightened natives fell to the ground from their tops. The Japanese, who tried to save themselves in the sea, got caught in the enemy fire in the middle of the surf. Only fifteen surrendered, eight hundred fell. Colonel Ichiki put an end to his misfortune with suicide. "

Sea Battle of the Eastern Solomon Islands (August 24-25, 1942)

While the Battle of Tenaru was still ongoing, there were further Japanese reinforcements on the way from Truk to Guadalcanal, including 1,600 men from the 28th Infantry Regiment and 500 marines. The convoy of three slow transport ships was protected by a fleet of 13 warships. In support of the landing planned for August 24, another fleet of over 30 warships ran out of Truk on August 21, including the three carriers Shōkaku , Zuikaku and Ryūjō . The Americans were able to oppose them with the two carriers Enterprise and Saratoga . In the subsequent carrier battle , which took place on August 24th and 25th, the Americans were able to sink the light carrier Ryūjō and thus secure their naval supremacy. The troop carriers, one of which was sunk, had to be diverted to the Shortland Islands by the Japanese .

The Japanese troop replenishment, mainly from Rabaul, was subsequently handled instead of transport ships mostly overnight with fast warships along the so-called slot , the strait between the Solomon Islands ( Tokyo Express ). Between August 29 and September 4, around 5000 men of the Japanese 35th Infantry Brigade under General Kawaguchi Kiyotake and the 4th Aoba Regiment reached Guadalcanal in this way . Kawaguchi was appointed commander in chief of all Japanese troops on Guadalcanal.

Battle of Bloody Ridge (September 12-14, 1942)

On September 7th, Kawaguchi announced the plan to attack Henderson Field to his commanders. This provided for a division of the troops into three groups, which should reach the American defense area on separate routes and strike together in a surprising night attack. The main force of three battalions with 3,000 men under Kawaguchi was to attack from the south and the other two groups from the west and east. Around 250 men were left to guard the landing point near Taivu.

After the Marines were informed of the presence of Japanese troops at Taivu by local scouts, the commander of the 1st Marine Raider Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Merritt A. Edson, organized a raid on September 8 , in which the Japanese main supply base participated after the guards left behind had been driven out the village of Tasimboko was tracked down and the supplies and communications equipment stored there destroyed. From the size of the camp and the documents captured, the Americans concluded that there were at least 3,000 Japanese soldiers who were believed to have set out to attack Henderson Field. Upon his return to Henderson Field, Edson, along with Vandegrift's operations officer Colonel Gerald C. Thomas, correctly predicted the main Japanese attack on a roughly one kilometer long, previously undefended coral bank near the Lunga River in the south of the area to be defended. Edson's battalion was accordingly transferred to this sector on September 11th.

On the night of September 12-13, a battalion of Kawaguchi's forces attacked Edson's raider near Lunga Ridge, forcing a company to retreat. The following night, Kawaguchi's entire group was attacked, supported by light artillery. The Japanese command post was only 2 miles from Henderson Field. Although the raiders had to back off at several points, they withstood the night-long attacks. The attacks by the other two Japanese groups also failed. On September 14th, Kawaguchi broke off the fight after losing 850 dead and led the remainder of his troops in a five-day march west to the Matanikau River. The Lunga Ridge was from now on called Edson's Ridge , due to the high losses also called Bloody Ridge .

On September 15, Hyakutake learned of Kawaguchi's defeat in Rabaul and passed the report on to the Japanese high command. In a crisis meeting, the army and naval command determined that the battle of Guadalcanal could develop into a decisive battle of the war. Hyakutake realized that he could not conduct offensive operations on Guadalcanal and New Guinea at the same time, and he decided, with the consent of Headquarters, to withdraw the troops on the Kokoda Track just 50 kilometers from Port Moresby until the situation on Guadalcanal was clarified. At the same time he prepared the dispatch of further troops to Guadalcanal. Two Japanese army divisions, the 2nd and the 38th , were transported from the Dutch East Indies to Rabaul from September 13th and were to be brought to Guadalcanal by means of the Tokyo Express in preparation for a new offensive planned for mid-October.

On September 15, the US carrier Wasp was torpedoed by the Japanese submarine I-19 south of Guadalcanal and sank a short time later. The Saratoga had already suffered a similar fate at the beginning of September , but was able to return to Pearl Harbor for repairs.

Operations on the Matanikau River (September 23 to October 9, 1942)

On September 18, 1942, after the arrival of the 7th US Marine Infantry Regiment, Vandegrift decided to undertake a counter-offensive with about 3000 soldiers against the 2000 Japanese buried near the Matanikau River. The Japanese defensive positions were reinforced by natural terrain difficulties such as towering hills, fields of sharp-edged elephant grass and ravines that stretch down to the coast.

On September 23, Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. Puller led the 7th Marine Regiment northwest of Henderson Field towards the mouth of the Matanikau, while Lieutenant Colonel Griffith of the 1st Marine Raider Battalion marched upstream against a Japanese bridge position. Lieutenant Colonel David McDougal, meanwhile, took up position on the east bank of the river. Griffith's operation was unsuccessful despite heavy artillery fire at the bridge and he had to withdraw downstream. To end the stalemate, Puller dispatched three companies under the command of Major Otho Rogers to land in Higgins boats behind the enemy . Rogers fell during this maneuver and his group was trapped on all sides by the enemy on an elephant grass hill.

With the help of air support, the combat group finally succeeded in liberating and flying out. The standstill between the two parties lasted 10 days before the Americans decided to resume the operation. The excavation work had meanwhile been completed, so that six battalions were ready for action on October 7, 1942.

On the other hand, General Hyakutake ordered Colonel Nakaguma with the 4th Infantry Regiment to counterattack, which was foiled by Colonel Edson's forces. The Americans succeeded in pushing into the flanks of the Japanese and ultimately driving them back to the western side of the river.

On October 8, the Japanese repeated their attack efforts in the midst of a heavy tropical rain, involved the Americans in bitter hand-to-hand fighting, but were again unable to cross the lines.

On October 9, 1942, Colonel Whaling secured the contested bridge after a month of unsuccessful effort. The marines under Whaling, Puller and Lieutenant Colonel Herman Hanneken were able to march across the secured bridge to the other side of the river, but found no more signs of Japanese infantrymen.

Another major Japanese attack was launched on October 12, 1942. Three combat groups were to attack the American troops concentrically on the Matanikau River. The operation on the Matanikau River was a total failure. While crossing the floodplain, the Japanese tanks were shot down and the mounted infantry were fought down with machine guns. The troops did not make any progress around Mount Austen in a labyrinth of rocks, man-thick lianas, hard giant trees and ravines.

Unobserved, the Japanese had withdrawn into two forest ravines, where they could defend the sea side, but were unprotected against an approach from the interior. The ravines in question were covered with heavy artillery fire, fleeing Japanese at the exits were struck down by US machine gunmen . About 690 Japanese were killed in the ravines. Around 120 US soldiers lost their lives during the Matanikau operation.

The loss of the Matanikau positions was viewed by the Tokyo High Command as a bad omen for the upcoming October offensive.

Sea Battle of Cape Esperance (October 11-12, 1942)

At the end of September and beginning of October 1942, the first units of the 2nd Japanese Division were brought to Guadalcanal by the Tokyo Express. The Japanese navy promised to support the army's operations not only by conviviality, but also by renewed air strikes and ship bombing of Henderson Field. At the same time, the Americans decided to strengthen their forces on Guadalcanal by sending additional army units. On October 8, the 164th Infantry Regiment of the Americal Division of New Caledonia set sail, accompanied by Task Force 64 under Rear Admiral Norman Scott , consisting of four cruisers and five destroyers.

On the night of October 11, the Japanese had planned a larger Tokyo Express convoy consisting of two aircraft mother ships and six destroyers. In another operation, three heavy cruisers and two destroyers under Rear Admiral Goto were to bombard Henderson Field.

Shortly before midnight, Scott's fleet spotted Gotō's ships on their radar screens just before they entered the strait between Savo Island and Guadalcanal. The Americans opened fire on the unsuspecting Japanese and were able to sink a cruiser and destroyer before the Japanese withdrew. Gotō was fatally wounded in the battle. Because of this battle, the Japanese supply convoy managed to carry out its mission undetected and to return unmolested. The American convoy also reached the island safely the next day.

Bombardment of Henderson Field (October 13-16, 1942)

Despite their defeat at Cape Esperance, the Japanese continued their preparations for the major offensive planned for late October. In a departure from their usual nightly supply trips with fast warships, they dispatched a fleet of six transport ships on October 13th, which were escorted by eight destroyers and had around 4,500 men from two infantry regiments, some marines, two batteries of heavy artillery and an armored company on board . To eliminate the threat posed by the Cactus Air Force aircraft , Admiral Yamamoto von Truk dispatched the two battleships Kongo and Haruna with an escort of a light cruiser and nine destroyers to bomb Henderson Field with their heavy artillery.

The battleships attacked Henderson Field on the night of October 14th, firing their 14-inch guns using frag grenades for over an hour . The almost 1,000 shells severely damaged the airfield, destroyed 48 of the 90 CAF aircraft, resulted in the loss of almost all aviation fuel supplies and killed 41 men, including six pilots. Immediately after the bombardment, the fleet began its return journey to Truk. Despite the severe damage to the airfield, emergency teams were able to make it usable for aircraft again within a few hours. Seventeen SBDs and 20 Wildcats were flown in from Espiritu Santo and Army and Navy transport machines began to shuttle large amounts of aviation fuel to Guadalcanal.

Having become aware of the large Japanese convoy, the Americans tried desperately to attack it with the aircraft that were left to them before it arrived. With the help of fuel reserves stored in the jungle, they attacked the convoy twice without success in the course of October 14. The convoy reached Tassafaronga at midnight on October 14 and began unloading. That night, as well as the following, Japanese heavy cruisers again fired at Henderson Field and destroyed several other aircraft, but were unable to significantly damage the airfield. For the whole of October 15, CAF aircraft attacked the transporters at low altitude and sank three of the ships. The remaining transport ships made their way back during the night after they had unloaded all the troops and around two thirds of the supplies and equipment.

Battle of Henderson Field (October 23-26, 1942)

Between October 1 and 17, the Japanese succeeded in bringing about 15,000 men to Guadalcanal, giving Hyakutake a total of 20,000 men for his planned offensive. After losing their positions east of the Matanikau, an attack along the coast seemed futile to the Japanese, which is why Hyakutake decided to attack the fence from the south. The 2nd Division under Lieutenant General Maruyama Masao , reinforced by troops from the 38th Division, was to carry out this task. The remaining troops, about 2900 men under Major General Sumiyoshi Tadashi, were supposed to attack the coastal strip as a diversion. The date of the attack was set for October 22nd and later postponed to the 23rd. Colonel Tsuji Masanobu , who had been sent by Japanese headquarters to get a personal impression of the situation, was also involved in the planning and management of the operation .

On October 12, a Japanese engineering company began to cut a 15-mile (15-mile) path through the jungle for Maruyama's troops, which ran through extremely difficult terrain. Around October 16, the division began its march into the staging area. After Hyakutake learned on October 23 that Maruyama's forces had not yet reached their designated positions, he postponed the attack again until the evening of October 24. Sumiyoshi was informed of the delay, but due to communication problems, his troops began their diversionary attack at the mouth of the Matanikau on October 23, which the Americans repulsed with relative ease.

Raymond Cartier on the Battle of the Matanikau River:

“The Navy was getting impatient. She declared that she could not leave her ships at sea indefinitely. When the army announced that it was not ready to attack on October 18, the navy responded with accusations. But when Maruyama declared that the twenty-third still seemed too early to him, they threatened to withdraw from the agreements made and to give up the company. Hyakutake lost his nerve. He ordered Maruyama to attack under whatever circumstances and let the Matanikau operation continue. In an attempt to cross the river over the alluvial land at its mouth, the Japanese tanks were shot down one after the other, the mounted men mowed down. As hard as the leather necks were, they felt sick at the sight of the crocodiles of Matanikau crawling around on the sandbanks between the corpses of fallen Japanese. When Colonel Oka's detachment crossed the Nippon Bridge, they got stuck in the jungle and could not make the sweeping movement that had been prescribed for them. Their commanding officer was blamed. "

During the night of October 24-25 and the following night, Maruyama's forces carried out continued frontal attacks on American positions to the south of the site, led by forces of the 1st Battalion of the 7th Marines under Lieutenant Colonel Puller and 3rd Marines. Battalion of the 164th Infantry under Lieutenant Colonel Robert Hall were defended. Almost without exception, the attacks were stuck in defensive fire from rifles, machine guns, mortars, artillery and anti-tank guns. Smaller Japanese groups that had broken into the fence were eliminated by the Americans over the next few days. More than 1,500 of Maruyama's men died in the attacks, while the Americans only had about 60 dead. Further Japanese attacks on Matanikau on October 26th were also repulsed with heavy losses for the Japanese. At 8:00 a.m. on October 26, Hyakutake ordered the futile attacks to cease. About half of Maruyama's remaining troops marched back west to Matanikau, the 230th regiment under Colonel Shōji Toshishige moved to a position east of the Lunga fence. The total casualties of the Japanese during the operation amounted to around 3,000 men.

Naval Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands (October 26, 1942)

At the same time as Maruyama's troops were taking up their attack positions, a Japanese carrier fleet took up position in the southern Solomon Islands to prevent the enemy naval forces from interfering with the impending land fighting. The American carrier groups, under the aggressive leadership of the newly appointed Commander Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, were indeed on the march and it was clear that a battle would ensue.

On the morning of October 26, the battle began with the exchange of several attack waves from the carrier fleets. Two of the four Japanese porters, the Shōkaku and the Zuihō , suffered severe damage, which made longer repairs in the Japanese home port necessary. The Americans who sent the Enterprise and the Hornet into battle suffered irreparable damage to the Hornet , which had to be abandoned. The Enterprise was also damaged, but after a brief repair in Nouméa was able to intervene in the fighting again in November. For the Japanese, the high losses of well-trained flight crews turned out to be a disadvantage in the further course, which made it necessary to return the two other porters Zuikaku and Jun'yō to Japan. In addition, they did not succeed in destroying Halsey's fleet with their superior forces, as would have been necessary, according to the state of the ground fighting, in order to turn the battle for Guadalcanal.

Land fighting in November (November 1st to 18th, 1942)

To take advantage of his victory in the Battle of Henderson Field, Vandegrift sent six battalions of marines led by Merrit Edson, later reinforced by an Army battalion, to operations west of the Matanikau. Their aim was to attack the headquarters of the 17th Army at Kokumbona, west of Point Cruz. The area was defended by the Japanese 4th Infantry Regiment, which was severely weakened by previous battles, tropical diseases and malnutrition.

The American offensive, supported by ships and aircraft, including B-17 bombers, began on November 1 and led to the destruction of the Japanese forces by November 3, so that the way to Kokumbona appeared to be open. However, the offensive was interrupted by Vandegrift on November 4th and the troops were ordered back to the fencing, as Japanese landings had been observed the day before at Koli Point in the east of the Lunga area, where a large number of Japanese troops were heading after the battle of Henderson Field . The American casualties in the Matanikau offensive up to this point amounted to 71 casualties, the Japanese around 400.

On November 4, four American battalions, under the overall command of Marines Brigadier General William H. Rupertus, were marched to Koli Point. The main part of Colonel Shōji's 230th Regiment had now arrived there, and they were bombed in their positions by US ships and aircraft. From November 5, the Americans began an encirclement operation that was to destroy Shōji's troops for good. Hyakutakes had meanwhile received orders to return to Kokumbona. The Japanese managed to find a loophole and break out of their grip between November 9th and 11th. Any survivors who stayed behind were killed by the Americans when the cauldron was closed. In total, the operation cost the Americans 40 dead and 120 wounded, while they found around 450 Japanese dead. On the way back, Shōji's men lost another 500 men to attacks by the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson, who had previously served as guardians for the later abandoned construction of an airfield at Aola Bay. When Shōji's troops had finally reached their own lines west of the Manatikau, they had melted down to 700-800 men from once more than 3000 due to constant attacks, hunger and disease.

The fighting at Point Cruz was resumed by the Americans around November 10th, but the Japanese managed to hold their lines with the help of reinforcements that had meanwhile arrived.

Naval Battles of Guadalcanal (November 13-15, 1942)

After their defeat in the Battle of Henderson Field, the Japanese army planned to resume the offensive with further reinforcements in November. For this purpose, the Navy provided eleven large transport ships, which were supposed to bring the rest of the 38th Division, around 7,000 men, including supplies and equipment, from Rabaul to Guadalcanal. Yamamoto also provided for Henderson Field to be bombarded again by battleships, this time Hiei and Kirishima . The fleet with the two battleships was commanded by Vice Admiral Abe Hiroaki .

Around the same time, the Americans sent a larger supply convoy called Task Force 67 under Rear Admiral Turner to Guadalcanal, which was accompanied by two task groups under Daniel Callaghan and Norman Scott. The convoy was attacked by Japanese planes, but was partially unloaded on November 12th. After being warned about the Japanese bombing group by aerial reconnaissance, the Americans gathered all available warships, including two heavy and three light cruisers and eight destroyers, to confront the Japanese south of Savo Island at night. At around 1:25 a.m., the Japanese ships were identified on the radar and came into view some time later. The Japanese were disadvantaged by the fact that their formation was mixed up after the journey through a rain shower and the two battleships had loaded fragmentation grenades rather than armor-piercing grenades. At about 1:48 a.m. both sides opened the battle at close range. In a confused battle that lasted about 40 minutes, some of which was conducted at close range, most American ships were badly damaged or sunk and both Callaghan and Scott were killed by direct hits on bridges. The Japanese lost two destroyers and the following day air strikes from Henderson Field and the Enterprise the damaged battleship Hiei . The planned attack on Henderson Field was prevented as the Japanese withdrew.

Yamamoto then had the transport ships, which should have landed on November 13th, wait another day to pass through the slot and sent another fleet under Kondō Nobutake to bomb Henderson Field on November 15th. On the night of November 14, a fleet of cruisers attacked Henderson Field below Mikawa, but caused no major damage. The next day, the Japanese troop convoy, which was escorted by a destroyer group under Tanaka Raizo , was attacked several times by US aircraft on its way through the slot and six of the ships were sunk. Most of the soldiers were taken up by the accompanying destroyers, around 450 drowned. One of Mikawa's heavy cruisers had previously been sunk by the aircraft on their return journey and one was badly damaged. Four transport ships and four destroyers continued their voyage to Guadalcanal, the rest returned to the Shortlands.

On the night of November 14th, Kondo's fleet, which had now united with Abes, headed for Guadalcanal through the Indispensable Strait . During the day, Halsey had parked the two battleships Washington and South Dakota along with four destroyers from the Enterprise's carrier group and transferred command of this Task Force 64 to Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee . The fleet was patrolling Savo Island when at around 10:55 p.m. Kondō's fleet, consisting of Kirishima , two heavy and two light cruisers and nine destroyers, appeared on the radar screens. At 11:17 p.m., the American battleships opened fire. Two American destroyers were sunk a short time later and one was badly damaged. After the South Dakota was badly damaged and turned, the Washington managed to cover the Kirishima with several salvos, so that it had to be sunk in the early morning when the Japanese withdrew.

The four Japanese transport ships landed at Tassafaronga around 4:00 a.m. on November 15, where they were attacked by US planes early in the morning and set on fire. About 2000 to 3000 soldiers went ashore, most of the equipment was lost. The sea battle of Guadalcanal was the last attempt by the Japanese to take control of the waters around Guadalcanal. They were no longer able to bring large numbers of troops to Guadalcanal.

Sea battle of Tassafaronga (November 30, 1942) and the Japanese decision to evacuate

The ongoing crisis on Guadalcanal prompted the Japanese to take countermeasures in November. On November 26th, the 8th Regional Army under Lieutenant General Imamura Hitoshi was set up in Rabaul, which should coordinate the actions of the 17th Army on Guadalcanal and the 18th Army in New Guinea. Due to an Allied offensive against Buna and Gona that began in New Guinea in mid-November, the priority of the fighting on Guadalcanal was downgraded by Imamura.

After the naval battles of Guadalcanal, the Japanese began to use submarines for nightly supply trips to Guadalcanal. Since these had only a very limited transport capacity, the 17th Army soon had a serious supply crisis. The destroyer fleet operating from the Shortlands under Tanaka Raizō was therefore commissioned to develop a new method for the supply trips. For this purpose, barrels loaded with supplies were used, which were to be transported by the destroyers near the beach and released there in order to be picked up by swimmers or boats. In this way, it was hoped to shorten the time-consuming process of unloading and thus to avoid air attacks. The first trip with the new method was scheduled for the night of November 30th.

Halsey had meanwhile re-formed Task Force 67 on Espiritu Santo with four heavy and one light cruisers and four destroyers and placed it under the command of Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright. On November 29th, the Americans intercepted a Japanese message announcing the Tanaka supply trip and instructed Wright to intercept the Japanese. Two other destroyers joined him on the way. Tanaka had received a warning about the Americans from a reconnaissance plane and was prepared for a battle.

The battle south of Savo Island began at around 11:15 p.m. After an unsuccessful torpedo attack by the American destroyers, the US cruisers took one of Tanaka's destroyers under fire and incapacitated it. The remaining Japanese destroyers, in turn, launched a torpedo attack on the American cruisers. They used the enemy muzzle flash to aim at their targets. Since the Americans did not make evasive movements, all four heavy cruisers received hits. One sank, the others were badly damaged. The Japanese destroyers then turned away without having carried out their supply mission.

Despite this defeat, the Americans managed to seriously disrupt further Japanese convoy journeys. On the one hand, barrels that had already been unloaded were caused to sink by air strikes, on the other hand, the Americans are now increasingly using PT speed boats to protect the waters around Guadalcanal. After three more unsuccessful destroyer voyages, the Japanese stopped their attempts. On December 12th, the Japanese Navy proposed to cancel the operation on Guadalcanal. Against the resistance of the army command, on December 31, Emperor Hirohito finally agreed to the decision of the Japanese headquarters to withdraw the remaining troops from the island and to build a new line of defense on New Georgia .

Last inland ground fighting (December 15, 1942 to January 23, 1943)

“In December, the Americans planned to capture Mount Austen, which should be completed within two weeks. Height 27, the hill known as the Galloping Horse, the Gifu position - they were all taken from the Japanese under equally difficult conditions. […] This remarkably successful [Japanese] evacuation did nothing to change the fact that the Americans had won one of the longest and most bitter battles in military history. […] The Americans lost only 1,492 deaths in the fighting, while the Japanese killed 14,800 soldiers and 9,000 were killed by disease. Midway had shown for the first time how brilliantly the Americans could do. Guadalcanal had clearly shown it a second time with its unspeakably harsh conditions and its ever new difficulties under completely different circumstances. The legend of the invincibility of the Japanese had been destroyed. "

The Japanese withdrew to the impassable mountain slopes of Mount Austen and suffered from tropical infectious diseases when the supply situation was catastrophic. The American ground offensive was limited to a few nests of resistance around Mount Austen : Height 27 “ Galloping Horse ”, “ Sea Horse ” and the “ Gifu position ”.

In his autobiographical novel " The Thin Red Line " (German translation under the title " Der tanzende Elefant ", filmed in 1998 by Terrence Malick ) James Jones describes in detail the struggles for " Galloping Horse " and " Sea Horse ", in which he himself as GI participated and in the course of which he was wounded (in his book, however, the two mountain ranges are called "the dancing elephant" and "the boiled king prawn") - including the raid troop company under Captain Charles W. Davis mentioned below (in the book "Captain Gaff") ).

The last fighting in the interior of Guadalcanal took place from December 15, 1942 to January 23, 1943. About 50,000 US soldiers fought against 20,000 Japanese soldiers who had retreated into the island's inaccessible mountains. While some 3,000 Japanese were killed in these operations, 250 Americans were killed. The focus of these battles was on the so-called Gifu position. The Japanese held their positions, which were positioned around tactically important mountain ranges such as Mount Austen, Galloping Horse and Sea Horse. While these positions were being held with the last of their strength, the main forces of the Japanese army withdrew from the island.

On the 416 m high Mount Austen (Japanese name "Bear Height", Mount Mambulu for the Solomonic inhabitants) a Japanese observation point was set up to investigate the movements of the enemy in the Lunga river delta and to direct artillery fire on Henderson Field.

Mount Austen was a group of hills densely overgrown with tropical mountain forest, in which individual rocks protruded from the vegetation and which were hardly accessible.

The supply was via a path that became known as the Maruyama Trail.

In early November 1942, under the command of Lieutenant General Tadayoshi Sano, parts of the Japanese 38th Division landed and intervened in the fighting over the Matanikau River. Another regiment under Major General Takeo Itō strengthened the defense positions around Mount Austen. Due to the sea battles only 2,000 to 3,000 soldiers were able to go ashore, the rest of the division and the heavy equipment remained outside Guadalcanal. Meanwhile, the American supply went almost undisturbed and three more regiments entered the island, including units of the 5th US Marine Infantry Regiment, the 25th US Infantry Division and the American Division .

From about December, the supply situation of the Japanese was highly tense and tropical diseases, hunger and exhaustion had the infantry - battalions losses of 50 men per day, so that approximately only 12,000 soldiers were operational.

On December 12, 1942, Japanese patrols succeeded in infiltrating the American lines and causing damage at the Henderson Field airfield. On December 14, 1942, the first gun battles between Americans and Japanese developed on the slopes of Mount Austen.

Major General Alexander M. Patch , who had been in charge of operations on the island of Vandegrift with his subordinate XIV. US Corps since the beginning of December, decided to destroy the remaining Japanese forces on the island in a large-scale operation. The 132nd US Infantry Regiment under Colonel Leroy E. Nelson was commissioned to permanently secure the mountainsides of Mount Austen.

The 3rd Battalion left its equipment in the control room and overcame some mountain slopes until it was held down by Japanese machine-gun fire.

The battalion managed to dig in during the night; it was under orders to direct artillery barrages on the Japanese-occupied mountain slopes.

Between December 20 and 23, 1942, the Japanese withdrew successively from their defense area at Mount Austen, as the armed US combat reconnaissance increased sharply.

They retreated into the trench system of Gifu Position, which was 1.4 kilometers from the top of Mount Austen and heights 27 and 31 and was secured by 45 to 50 interconnected and well camouflaged fire posts, which were arranged in a horseshoe shape. Strong mortar groups were positioned behind the trenches, which were difficult to make out in the natural vegetation.

In the period from December 25 to 29, 1942, the Japanese lines successfully withstood all enemy approaches in a frontal attack with a failed attempt to take the flanks. 53 US soldiers were killed and 129 were seriously wounded.

Another attempt was made on January 2, 1943, and the 2nd Battalion of the 132nd Infantry Regiment was able to capture Hill 27 and eliminate a mortar crew. The ammunition was running out and the soldiers had to assert themselves under difficult conditions. It was only through a change in leadership at battalion level that Lieutenant Colonel George managed to break into the Japanese lines. The losses of the 132nd Infantry Regiment rose to 115 killed and 272 wounded. A high proportion of the losses resulted from wound infections and tropical diseases.

The 1st and 3rd Battalions were so badly affected that they were taken out of action.

The Gifu position was enclosed by Americans on January 4, 1943, from the north, east and south. The irresponsible behavior of Major General Patch and the heavy losses by the US military leadership were later condemned.

The Japanese casualties were estimated at 500 casualties, although it remained unclear whether they were caused by fighting or starvation and exhaustion.

In January 1943, US operations shifted to the hilly area on the upper reaches of the Matanikau River, where heavily defended Japanese positions were on the hills "Galopping Horse" and "Sea Horse".

Major General J. Lawton Collins , commander of the 25th US Infantry Division, instructed the 35th US Infantry Regiment to take the remains of the Gifu position, remaining Japanese resistance nests on Mount Austen and the hill "Sea Horse". The 27th US Infantry Regiment was deployed against the "Galopping Horse" hill. Both regiments were supposed to unite on hill 53, which to a certain extent represented the head of the hill "Galopping Horse". The 161st US Infantry Regiment was to remain in reserve. With great effort, slopes were cut in the rainforest to ensure supplies for the front units.

The Japanese were waiting for the US offensive and began to strengthen their positions around the Matanikau River. The Japanese high command hoped to lure the US troops into ambushes and defeat them from well-developed positions in night firefights and hand-to-hand combat before they could exploit their technical superiority in firepower.

The Galopping Horse hill formation consisted of hills 54, 55 and 57, with the 270 meter high hill 53 in the middle. Col. William A. McCulloch, commander of the 27th Infantry Regiment, deployed his battalions against Hills 57, 51 and 52, which were defended by approximately 600 Japanese from the 228th Infantry Regiment under Major Haruka Nishiyama.

The American attack began early in the morning on January 10, 1943 with massive artillery fire. Near Hill 52, the American advance was halted by Japanese machine guns that could only be destroyed by air strikes. Hill 51 was taken without enemy resistance.

On January 11, 1943, Japanese machine guns and mortars held down the 3rd Battalion for a long time, due to the lack of water, the US soldiers were hardly ready for action.

Hill 53 fell the next day. The axis of rotation of the Japanese defense line was not far from Hill 53 at the "horse neck" of the hill formation "Galopping Horse" and was secured against the American advance by heavily fortified machine gun nests and mortar positions.

It was only through the deployment of a four-man volunteer squad under Captain Charles W. Davis that Hill 53 was taken into American possession. The arrival of the water supply and the news of the victory of the Davis Command spurred the US soldiers to make further efforts to proceed. This operation cost less than 100 American casualties and 170 fallen Japanese soldiers.

Between January 15 and 22, 1943, the 161st Infantry Regiment carried out cleanups against enemies who had left the area.

In the last weeks of December 1942, Colonel Robert B. McClure (35th US Infantry Regiment) was tasked with conquering the "Sea Horse" hill group, which consisted of hills 43 and 44, and the Gifu position. Several units should approach the gifu position on different routes and eliminate it.

The routes consisted of narrow paths that were actually only sufficient for small reconnaissance troops and led over a rainforest landscape that was difficult to penetrate and steep mountain slopes. The 3rd Battalion was the first to manage to approach the top of the hill at 640 meters and excavate positions. On January 11th, with the help of air support and artillery fire, Hill 43 was captured at night. The victory was announced on January 12, 1943, although 558 fallen Japanese soldiers were counted, parts of the Japanese regimental staff were able to withdraw.

On January 9, 1943, there was the second battle on Mount Austen against the last nests of resistance of the Japanese army in the remnants of the Gifu position. With the capture of the "Sea Horse" hill, the Japanese were cut off from the rest of the 17th Army. The surviving Japanese were ordered to defend their positions to the last resort. Loudspeaker calls from Americans to surrender were ignored.

On the afternoon of January 17, 1943, the final American offensive began with strong cannon fire and on January 18, the break-in took place at the weakest point of the Gifu Line. Due to heavy rain, the attack had to be stopped on January 20, 1943.

The last resistance was broken on January 22nd, 1943, when a light US tank was laboriously brought over the path to a mountainside of Mount Austen and destroyed the last bunkers of the Japanese. The total Japanese casualties at the Gifu position were estimated at 1,500 soldiers. This eliminated the resistance of the Japanese in the interior of the island.

In mid-January the Japanese began their retreat from the hill positions to the west in preparation for the evacuation of the island ( Operation Ke ). The troops were brought to New Georgia on destroyers in three stages on February 1st (approx. 5,000 men), 4th (approx. 5,000 men) and 7th (approx. 2,500 men) . This ended the months-long struggle for the island.

consequences

With their victory on Guadalcanal, the Americans were finally able to secure the sea route between Australia and America. Guadalcanal became an important starting point for the following Allied operations against the Northern Solomon Islands , eastern New Guinea and Rabaul , the Japanese main base in the South Pacific. These were carried out from June 1943 as Operation Cartwheel , which lasted until 1944.

The Battle of Guadalcanal was one of the longest and most bitter in American military history. The American casualties in the ground fighting are given as 1,492, those of the Japanese as 14,800.

The airfield that was contested at the time is now the civil airport of Honiaras , the capital of the Solomon Islands. The old name Henderson Field was only changed to Honiara International Airport in December 2003, despite protests from many American veterans .

Movies

motion pictures

- Guadalcanal - Hell in the Pacific (Guadalcanal Diary) , USA, 1943 Directed by Lewis Seiler ; Actor Anthony Quinn , Richard Jaeckel . 93 min.

- Steel wings (Flying Leathernecks) , USA 1951: Director Nicholas Ray ; Actor John Wayne , Robert Ryan . 102 min. Major Kirby (John Wayne) leads aMarines Wildcat squadron into the battle for Guadalcanal.

- Vacation Until We Wake Up (Battle Cry) , USA 1955: directed by Raoul Walsh ; Starring Van Heflin , James Whitmore , Aldo Ray . 121 min. Film adaptation of the novel Battle Cry by Leon Uris , who also wrote the screenplay. The novel is based on his own wartime experiences as a marine.

- The Thin Red Line (The Thin Red Line) , USA, 1998. Directed by Terrence Malick ; Actors Sean Penn , Nick Nolte , John Savage , John Travolta , George Clooney . 170 min. The Battle of Guadalcanal forms the background of the anti-war novel The Thin Red Line (German title: Insel der Verdammten ) by the American writer James Jones , who himself took part in the fighting. The book was filmed with the original title in 1964 by Andrew Marton and successfully filmed by Terrence Malick in 1998.

- The Pacific , USA 2010 - 10-part miniseries from pay-TV broadcaster HBO about the Pacific campaign of the US armed forces in World War II. Like Band of Brothers , the miniseries was producedby Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks . Part 1 and Part 2 of the miniseries are about the landing and the battle for Guadalcanal.

documentation

- Victory at Sea , USA 1952/53. Miniseries in 26 30 min episodes about the naval war 1939–1945. Was u. a. known for the music. (6 DVDs)

- Battle Group: Halsey , USA 2001. Director: Wayne Weiss . Documentation about Admiral William Halsey , speaker is Miguel Ferrer . 90 min.

- Battlefield - Guadalcanal , 2004 (DVD)

- Robert D. Ballard: National Geographic - The Lost Guadalcanal Fleet , 1993 (video)

- James Bradley: Our fathers' flags

literature

- Eric Hammel: Carrier Clash. The Invasion of Guadalcanal & the Battle of the Eastern Solomons August 1942. Zenith, St. Paul (Minnesota) 2004, ISBN 0-7603-2052-7 .

- Eric Hammel, Guadalcanal: Decision at Sea. The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, Nov. 13-15, 1942. Pacifica, Pacifica 1999, ISBN 0-935553-35-5 .

- James W. Grace: The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. Night Action, November 13, 1942. Naval Institute, Annapolis 1999, ISBN 1-55750-327-3 .

- Carl K. Hixon: Guadalcanal. An American Story. Naval Institute, Annapolis 1999, ISBN 1-55750-345-1 .

- Russell Sydnor Crenshaw: South Pacific Destroyer. The Battle for the Solomons from Savo Island to Vella Gulf. Naval Institute, Annapolis 1998, ISBN 1-55750-136-X .

- John Miller: Guadalcanal. The First Offensive, the US Army in WW II. Center of Military History, Washington 1995, ISBN 0-7881-5007-3 (reprint of 1949 edition).

- Richard B. Frank: Guadalcanal. The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. Penguin, New York 1990, ISBN 0-14-016561-4 .

- John B. George: Shots Fired In Anger: A rifleman's view of the war in the Pacific , 1942-1945, including the campaign on Guadalcanal and fighting with Merrill's Marauders in the jungles of Burma. National Rifle Association, 1981, ISBN 0-935998-42-X .

- Samuel B. Griffith: The Battle for Guadalcanal . Champaign, Illinois, USA: University of Illinois Press, 1963, ISBN 0-252-06891-2 .

Web links

- NAVY page about Guadalcanal ( Memento from December 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- Extensive documentation on ibiblio.org (English)

- Diary of a Japanese veterans (English)

- "Guadalcanal: The first offensive", publication of the Center of Military History United States Army (English)

- Photos and descriptions of the theaters of war on Guadalcanal then and now (English)

- Frank O. Hough: "Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal". History of US Marine Corps Operations in World War II. (English)

- Report of a Japanese participant in the fight (German)

Individual evidence

- ^ David Kennedy: Freedom from Fear - The American People in Depression and War . Oxford 1999, pp. 549f

- ^ Raymond Cartier: The Second World War. Vol. 2 1942–1944, Lingen Verlag, Cologne 1967, p. 606.

- ↑ The Japanese thought Americans were effeminate whites, quote Ichiki: " Americans are soft, Americans will not fight, Americans believe that the nights are there for dancing ."

- ↑ a b c http://www.thetigerisdead.com/teneru.html

- ^ Samuel B. Griffith: Battle for Guadalcanal, Illinois, USA: University of Illinois Press, 1963 p. 102.

- ↑ Frank O. Hough: Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 290 in http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/I/index.html

- ↑ Michael T. Smith: Bloody Ridge, The Battle That Saved Guadalcanal. New York, 2000, pp. 58-59.

- ↑ Stanley Coleman Jersey: Hell's Islands: The Untold Story of Guadalcanal. College Station, Texas, Texas A&M University Press, 2008, p. 137.

- ↑ Michael T. Smith: Bloody Ridge, The Battle That Saved Guadalcanal. New York, 2000, pp. 62-63.

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, p. 153.

- ^ Samuel B. Griffith: Battle for Guadalcanal, Illinois, USA: University of Illinois Press, 1963 pp. 103-104.

- ↑ http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/USMC-M-Guadalcanal.html

- ^ Samuel B. Griffith: The Battle for Guadalcanal. Champaign, Illinois, USA: University of Illinois Press, 1963, p. 106.

- ^ Frank O. Hough: Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 156.

- ^ Samuel B. Griffith: Battle for Guadalcanal, Illinois, USA: University of Illinois Press, 1963 p. 107.

- ↑ http://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=9

- ^ Raymond Cartier: The Second World War. Vol. 2 1942–1944, Lingen Verlag, Cologne 1967, p. 607.

- ↑ US Marine Raiders - Commanding Officers ( July 19, 2012 memento in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/Guadalcanal/USMC-M-Guadalcanal-6.html

- ^ Raymond Cartier: The Second World War. Vol. 2 1942–1944, Lingen Verlag, Cologne 1967, p. 609.

- ^ Raymond Cartier: The Second World War. Vol. 2, 1942-1944, Lingen Verlag, Cologne 1967, pp. 615-616.

- ↑ James Jones: " The Thin Red Line ". Scribner, New York 1962, ISBN 0-385-32408-1 . (From the American by Günther Danehl: Der tanzende Elefant . S. Fischer, Frankfurt a. M. 1963, later title: Insel der Verdammten , ISBN 3-596-14188-5 .)

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , pp. 421-425.

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , pp. 428-492.

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , pp. 493-527.

- ↑ Frank O. Hough: "Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal". History of US Marine Corps Operations in World War II , p. 364 f.

- ↑ John Jr. Miller, "Guadalcanal: The First Offensive". United States Army in World War II. Online , 1949, pp. 237-238.

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , p. 530.

- ↑ John Jr. Miller, "Guadalcanal: The First Offensive". United States Army in World War II. Online , 1949, pp. 239-240.

- ^ A b John Jr. Miller: "Guadalcanal: The First Offensive". United States Army in World War II. Online , 1949, p. 237.

- ↑ John B. George: Shots Fired In Anger: A rifleman's view of the war in the Pacific, 1942-1945, including the campaign on Guadalcanal and fighting with Merrill's Marauders in the jungles of Burma. National Rifle Association, 1981, ISBN 0-935998-42-X , p. 106.

- ^ Samuel B. Griffith: The Battle for Guadalcanal. Champaign, Illinois, USA: University of Illinois Press, 1963, ISBN 0-252-06891-2 , p. 267.

- ↑ John B. George: Shots Fired In Anger: A rifleman's view of the war in the Pacific, 1942-1945, including the campaign on Guadalcanal and fighting with Merrill's Marauders in the jungles of Burma. National Rifle Association, 1981, ISBN 0-935998-42-X , p. 128.

- ^ A b Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , p. 552.

- ^ A b Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , p. 553.

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , pp. 553-554.

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , pp. 554-555.

- ^ A b Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , pp. 555-558.

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , p. 562.

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , pp. 562-563.

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , p. 564.

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , p. 565.

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , pp. 565-566.

- ^ Richard Frank: Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House, 1990, ISBN 0-394-58875-4 , pp. 566-567.

Coordinates: 9 ° 37 ′ S , 160 ° 17 ′ E