Tarnowo School

As the school of Tarnowo ( Bulgarian Търновска художествена школа Tarnowska chudoschestwena schkola ) is the art-historical period in Bulgaria during the time of the Second Bulgarian Empire (1185-1396). It is closely related to its rise and fall.

Even though the Second Bulgarian Empire was shaken by wars, revolts, and the strivings for power of individual feudal rulers, architecture , art and literature , music and spiritual life experienced a brisk development. With the restoration of the Bulgarian Empire in 1185, the influence of Byzantium in Bulgarian art came to an end and the art of the First Bulgarian Empire (679-1018) continued. The art school of Tarnowo developed not only in the court schools around the new capital of the empire - Tarnowo , whose name they also bear. The main difference to Byzantine art consists in the richness of the decorative tendencies of the Tarnow School, in which it was decisive.

With the fall of Vidin after the Ottoman victory in the battle of Nicopolis in 1396, the Second Bulgarian Empire and with it his art perished. The cultural achievements that had manifested themselves in all areas in the 14th century contributed to the Bulgarian part of European civilization.

history

In the middle of the 12th century the Bulgarian tsars managed to regain their old political and military strength, which was culturally consolidated through the building of numerous churches , monasteries and palaces throughout the empire. Tarnowo was one of the most important pilgrimage sites on the Balkan Peninsula in the Middle Ages . At that time, according to contemporaries, Tarnowo was a new Jerusalem , Rome and Constantinople at the same time . Numerous relics of saints, including those of Saint Sava of Serbia , Saint Demetrios of Thessaloniki , Saint Petka , or that of Saint Ivan Rilski were buried here in specially built buildings. The Tarnowo painting school and book decoration also reached a high point in the 13th to 14th centuries. Their representatives exceeded the traditional rules of traditional icon painting and thus created the most important independent school of Eastern church art.

After the advance of the Ottoman Turks, Bulgarian scribes, architects, painters and builders emigrated from the areas of Tarnowo, Widin and Dobruja to the surrounding countries and influenced the cultural development there considerably, for example in Serbia , Wallachia , Moldova , Transylvania and Russia . Today only a few masterpieces (buildings, icons, manuscripts) of this cultural bloom of Bulgarian culture have survived the centuries-long rule of the Ottoman Turks. Many of them are abroad.

architecture

Architectural witnesses from the time of the Second Bulgarian Empire are numerous fortresses and palaces, monasteries and churches. In Vidin there is the Baba Wida fortress , which was renewed again and again in the following centuries due to its strategic location. On the northern slope of the Rhodope Mountains on the road that led to the Batschkowo monastery and the Aegean Sea, Tsar Ivan Assen II had the Asenova fortress built, from which only the two-story court chapel has survived today. The oldest part of Rila Monastery , the Chreljo Tower, is named after its builder from 1355. Parts of the Shumen fortress were also rebuilt at this time.

The capital Tarnowo experienced a special design. The city, located on the Jantra River , extended over three plateaus enclosed by it: Trapesiza , Tsarevets and Sweta Gora (from the Bulgarian Holy Mountain), where the numerous monasteries were located.

Sacred architecture

The heyday of architecture during the Second Bulgarian Empire led to the construction of over 25 churches in its capital Tarnowo alone. On the Mesemvria peninsula (now Nessebar ) in the Black Sea , only ten of the original 40 churches have survived . On the small territory of Melnik there were 64 churches and 10 chapels within the fortress wall. The large number of churches, which were often only the size of chapels, is characteristic of the Bulgarian Middle Ages. They were foundations of private piety, not parish churches in the usual sense.

The architects of the Ternow School took over from Byzantium a smaller, mostly single-nave type of church, the vaults and arches of which lead to the dome . Examples of cross -domed churches are the Nikolauskirche in Melnik , the Pantokratorkirche and Johannes-Aleiturgetos-Kirche in Nessebar as well as the 40-Martyrer-Kirche in Tarnowo. However, they remained in contrast to the Byzantine art in the decorative tendencies in sacral architecture determinative (colorful, decorated with glazed ceramics exposed brickwork , blind niches and -arkaden). The outer walls are structured by blind arches and magnificent ornaments, which show a typical rhythmic alternation of red and white stones, bricks or even ceramics.

Another example is the Tsar's Church of the Holy Forty Martyrs in Tarnowo, which was built during the reign of Tsar Ivan Assen II and was artistically decorated. The reason for its construction was the Tsar's victory over Byzantium in 1230 in the Battle of Klokotnitsa . He had a victory column built in which glorified his victories and the greatness of his empire.

Visual arts

Frescoes

Despite the comparatively few frescoes that have survived today , they can be assigned to a Tarnowo school according to certain characteristics . Painting achieved greater independence in the frescoes in the church of Bojana (1259), the monastery church in Zemen (1354) or the cave churches of Iwanowo . The painting in the church of Bojana, executed in pure fresco technique ( fresco buono ), is one of the best preserved from this period in Southeast Europe and has Renaissance-like features. The frescoes in the rock churches near the village of Iwanowo (shortly after 1232, donated by Tsar Iwan Assen II. ) Prepared the ground for the artistic renaissance among paleologists at the end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th century. The frescoes in St. John's Church in Zemen are interspersed with pre-iconoclastic elements. The iconographic fidelity to tradition is combined with realistic features , especially in the pictures of the donors . The emotional is expressed more strongly. Many researchers compare the style with the Italian painting of the early Renaissance or the Trecento .

For the first time, tempera was used in wall painting by the Tarnowo Art School, which then quickly spread to the rest of the Orthodox world.

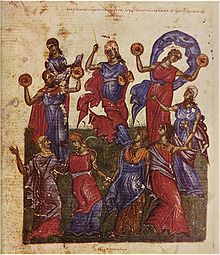

Book illumination

These stylistic features were also carried over into book illumination, which flourished for the last time in the reign of Tsar Ivan Alexander (1331–1371). In the literature school established near Tarnowo, numerous manuscripts , chronicles and codices with miniatures were produced. From the masterpieces created in the courtly scriptoria , a number of splendid, illuminated manuscripts have been preserved. Among the most famous works are the codices of the Manasses Chronicle, commissioned by Tsar Ivan Alexander (around 1345, now in the Vatican), the Ivan Alexander Gospel , also known as the Tetra Gospel (around 1356, now in London in British Museum), the Tomić Psalter (around 1360, now in Moscow) and the Sofia Psalter , which is the only one in Bulgaria.

Icons

The tradition of icon design from the First Bulgarian Empire was also continued in the Tarnowo School, which it perfected. Examples such as the "Mother of God Eleusa" (13th century) from Nessebar, which today belongs to the icon collection of the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Sofia , or the icon of St. Ivan Rilski (14th century), which is now in the monastery, bear witness to this Rila is located. It already shows a stronger realism with a tendency towards freer design, which has its parallel in the frescoes of the Boyana Church.

Another example of the superiority of the Tarnow painting school was shown by the large-format icons, which, with their immediacy and clarity, achieve a fascinating effect on the viewer. The icon of the "Mother of God with the Evangelist John", which is now also kept in the crypt of the Sofia Cathedral and is also known as the Poganowo Icon , was created around 1395. It is double-sided and has a size of 93 × 61 cm. It represents a crucifixion and is characteristically kept in a balanced blue color.

However, the external shape of the icons was not tied to a specific material or the principle of panel painting that is common today . The famous ceramic icons from the Preslav school were also popular during the Tarnow period. The icons, which were created on a wooden base, were almost always made using a similar technique. While icons for domestic use usually have a portrait format of 30 × 35 cm, those for church rooms and there in particular for the iconostasis can take on larger dimensions.

However, Bulgarian icon painting reached its peak during the period of the Bulgarian revival .

Literature and language

Bulgarian literature experienced its second heyday during the Tarnovo School. In the spirit of early humanism , in literature, as in theology, there was a return to the origins. Linguistic, orthographic and stylistic reforms were carried out, which resulted in revision of the liturgical texts.

The appreciation of historiographical works is also characteristic of this epoch , such as the chronicles of the leading Byzantine historians (including Konstantin Manasses, Johannes Zonaras), which were enriched with events from Bulgarian history. Translators were found all over the country, but especially in the monasteries around Tarnowo and on Holy Mount Athos .

The most important ecclesiastical authors came from the college for scribes and clergy in Kilifarewo monastery near Tarnowo, founded by the Tarnow Patriarch Theodosios during the time of Tsar Ivan Alexander . Among them was Konstantin von Kostenez, the man who 300 years earlier recommended the vocal teaching system as a Western teacher and who became the founder of the Serbian literary school of Rasava. Among many famous students, the later Metropolitan of Moscow Kiprian , the later Metropolitan of Kiev and Lithuania Grigorij Camblak and the last Bulgarian Patriarch Euthymios , who revised the Central Bulgarian language , the so-called orthography of Tarnowo, stand out. The grammatical rules established by the Tarnowo orthography became the basis of Church Slavonic in the neighboring countries.

After the conquest of Bulgaria by the Ottoman Turks and the monks and scholars fleeing from them in large numbers, the achievements of Bulgarian literature became the basis for further development in the areas of today's states of Romania , Moldova and Serbia , so that one of a "second South Slav Influence ”on Ukraine and Russia.

Handicrafts

Due to the few surviving monuments of ecclesiastical handicrafts from the Second Bulgarian Empire, only limited conclusions can be drawn about its stylistic and formal developments. In all the work that has survived, however, there is a strong bond with the tradition of handicrafts of the First Bulgarian Empire. The silver fittings of the icons from Ohrid, Tarnowo and Nessebar show iconographic and stylistic features of the art of the past epoch, even if certain mannerist traits, together with a hardening and stiffening of form, appear that characterize the entire art of Bulgaria in the late 14th century .

The small metal sculpture of the Second Bulgarian Empire is even more conservative. Her works of art - jewelry, miniature icons, seals and coins - remain completely in the continuity of ancient times, unaffected by the change in style of Byzantine palaeological art . The Bulgarian goldsmiths repeatedly resort to the traditional zoomorphic motifs and the early Christian iconography of their prototypes, such as the Mother of God Hodegetria , Christ Pantocrator and Saint Dimetrius, many of which are reproduced on seals and coins until the end of the 14th century.

music

The 14th century also brought some innovations in music. However, the Orthodox Church fundamentally rejects instrumental music in worship. Only the human voice should proclaim the praise of God. The system of Byzantine church chant was passed on to the Eastern Slavs through modifications and adaptations via Bulgaria . The name “bolgarskij raspev” (Bulgarian way of singing) still reminds us of this way of tradition. The old neum system was reformed by the Athos monk Ioan Kukuzelis , who was born in Durrës in 1302 , by creating a new notation. For his mother he created the first traditional secular song of the Bulgarians, a kind of cantata , "The Lament of the Bulgarians".

See also

Literature sources

- Assen Cilingirov: The Art of the Christian Middle Ages in Bulgaria: 4th to 18th century; Architecture, painting, sculpture, handicrafts. Beck, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-406-05724-1 .

- Gerhard Ecker: Bulgaria. Art monuments from four millennia from the Thracians to the present. DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1984.

- Gerald Knaus: Bulgaria. Beck, Munich 1997, p. 53.

- Vera P. Mutafchieva: Bulgaria. A demolition. Publishing house Anubis, Sofia 1999, ISBN 954-426-195-8 .

- Hans-Joachim Härtel, Roland Schönfeld: Cultural bloom - the school of Tarnovo. In: Bulgaria. From the Middle Ages to the present. Friedrich Pustet Verlag, Regensburg 1998, ISBN 3-7917-1540-2 , pp. 64-67.

To architecture

- Aleksandar Popow, Jordan Aleksiev: Царстващият град Търновград. Археологически проучвания. Publishing house Nauka i izkustwo, Sofia 1985.

- Margarita Koewa: 2000 godini hristianstwo. Prawoslasnite Hramowe po balgarskite Zemi. (from the Bulgarian 2000 години христианство. Православните храмове по българските земи). Akademiker Verlag Marin Drinow, Sofia 2002.

- Reinhardt Hootz: Art Monuments in Bulgaria. A picture manual. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-422-00383-5 .

- Nikolaj Ovtscharow : Tarnovgrad - the second world city after Constantinople. In: History of Bulgaria. Brief outline. Lettera Verlag, Plovdiv 2006, ISBN 954-516-584-7 .

further reading

- Donka Petkanowa: Starobălgarska literatura: IX - XVIII vek. Publishing house Sv. Kliment Ochridski, 1992

- Gerhard Podskalsky: Theological literature of the Middle Ages in Bulgaria and Serbia 815-1459. Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-45024-5 .

- Konstantin Manasses: The Slavic Manasses Chronicle. after the edition by Joan Bogdan / with e. Inlet by Johann Schröpfer. Fink, Munich 1966.

- Konstantin Manasses: fototipno izd. na Vatikanskija prepis na srednobalg. prevod. Publishing house BAN, Sofia 1963.

- Penjo Rusew: Estetika i majstorstvo na pisatelite ot Evtimievata knižovna škola. BAN, Sofia 1983.

- Emil Georgiew : Literaturata na Vtorata bălgarska dăržava.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Gerhard Podskalsky : Theological literature of the Middle Ages in Bulgaria and Serbia 815-1459. Munich, Beck, 2000, ISBN 3-406-45024-5 , p. 74.

- ↑ Graba, A. La peinture religiouse en Bulgarie., Paris, 1928, p. 95.

- ^ Gerhard Ecker: Bulgaria. Art monuments from four millennia from the Thracians to the present , DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne, 1984, p. 99.

- ^ Nikola Mawrodinow: Old Bulgarian Art. Volume II (from the Bulgarian "Старобългарско изкуство", Том II), Nauka i Izkustwo Publishing House, Sofia, 1959

- ↑ Härtel / Schönfeld: Cultural bloom - the school of Tarnovo in Bulgaria pp. 64–67.

- ↑ Representation of animal forms by means of ornaments