Solunt

Solunt ( Greek Σολοῦς Solus , Latin Soluntum , Italian Solunto ) was an ancient city in Sicily in the municipality of Santa Flavia on the north coast, about 15 km east of Palermo . The place is a popular destination for tourists. The city, preserved today as ruins, was founded in the 4th century BC. Chr. By Carthaginians founded. At the end of the 4th century BC Greek soldiers were settled there in the 3rd century BC. Chr. The city came under Roman rule . Excavations mainly took place in the 19th century and in the middle of the 20th century. Around half of the urban area has so far been exposed and is relatively well preserved. The remains represent a good example of an ancient city where Hellenistic , Roman and Punic traditions mixed together.

Location and dates

Solunt is located on the north coast of Sicily, 18 kilometers east of Palermo and on the eastern slope of the 374 meter high Monte Catalfano, where it forms a plateau. The city is therefore close to the sea. Because of its altitude, it was easy to defend. It was once about 10 hectares in size, about half of the urban area has been excavated.

Surname

The city appears in the ancient sources under different names. In Thucydides it is called Σολοῦς (Solus). On coins and in Diodorus it is referred to as Σολοῦντνος (Soluntos). The Phoenician name of the city is passed down as Kfra on coins, which means Kafara village.

history

The Phoenicians founded, according to Thucydides in the 8th-7th Century BC The city. They had established several trading posts in the west of Sicily, including Motye and Panormus (Palermo). It was probably initially a question of smaller ports that did not pose a threat to the Greeks who were spreading across Sicily. In the 6th century BC The Phoenicians in the east of the Mediterranean area became part of the Persian Empire . The western Phoenicians (called Punians by the Romans ) became independent and Carthage in particular developed into an important city, which from an unspecified point in time gained control over the Phoenician places in Sicily. These places therefore became a threat to the Greeks of Sicily. The first violent clashes between Greeks and Carthaginians took place in the 6th century BC. Occupied.

The location of Solunt at this time was uncertain for a long time, but it is not identical with the later city, as no archaic remains have been found there so far . More recent excavations have uncovered Punic tombs on the Solanto hill south of the city. The archaic city is believed to be in this area today.

In 409 BC The Carthaginians attacked Sicily and were able to take several Greek cities such as Akragas and Gela . After a brief peace, the Carthaginians besieged in 398 BC. BC Syracuse , but the local tyrant Dionysius I was able to repel them, recapture large parts of the lost territory and even invade Punic areas. 397/396 BC BC Dionysius I also destroyed Solunt. A few decades later, in the middle of the 4th century BC. BC, the city was rebuilt at its current location. The Carthaginians settled there in 307 BC. BC veterans of Agathocles who had driven them from Africa .

During the First Punic War , Solunt was in 254 BC. BC Roman . Especially in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC The city seems to have experienced its heyday and was equipped with numerous typical buildings of a Hellenistic- Roman city. The theater and a new stoa were added in the 2nd century BC. Built in BC. At around the same time, the large Zeus / Baal statue was also consecrated in a local temple. In the 1st century BC Thermal baths were built; From this century, artistically high-ranking wall paintings come from a private house.

The city's bloom is in contrast to other places in Sicily. In pre-Roman times, Sicily was permanently involved in wars. Located on a mountain, a city was easy to defend, but the supply of goods of any kind was very difficult. Obviously, in peacetime it was much more convenient to live in the valleys. Many Greek settlements that had been founded on mountains were therefore abandoned during the long Roman peace period. This happened mainly in the 1st century BC. Chr. Solunt is an exception; At that time it was still inhabited by wealthy citizens, as the rich furnishings of various residential buildings testify to. In Cicero , the city as the capital of Civitas mentioned at the time when Verres v in the years 73-71. Was governor of Sicily.

A decline can be observed in the 1st century AD. During this time there were hardly any large new buildings worth mentioning. After all, the thermal baths were renovated and maybe even new ones were built near the agora. There is no evidence of further larger new buildings. The city is mentioned by Pliny , Ptolemy and in the Antonini Itinerarium in the 1st, 2nd and the beginning of the 3rd century AD. The town also has a Latin dedicatory inscription by the citizens to Fulvia Plautilla , the wife of Emperor Caracalla . After that the city was abandoned. Armin Wiegand suspects an earthquake or a landslide as the cause.

A few Greek inscriptions with the names of wealthy citizens come from the city. From Antallos, son of Asklapos, from the Ornichoi family, we learn that he paid for the paving of the main street from his own means. Another Greek inscription names " Sextus Peducaeus ", who lived from 76 to 75 BC. Was governor in Sicily.

The city minted its own coins , including numerous silver coins . The coins from the Punic period, which in the 5th century BC Started , bore the Punic inscription Kfra , sometimes with the Greek name Σολοντινον. In Roman times it became Σολοντινων. There were mainly didrachms (Zweierdrachme, drachma worth two drachmas) and oboli marked (coin worth one-sixth of a drachma) of silver. The bronze emissions consisted of hemilitrons (half of a litra; litra was a unit of coin and value mainly used in the Greek colonies) and tetras (a quarter of a litra). A second phase of coinage dates from the 4th to about the middle of the 3rd century BC. Primarily silver coins were produced. Hercules was a frequent motif ; maritime motifs like the hippocampus were also very popular. The last phase of coin production extended into Roman times. Preferred motifs were Poseidon , Athene and perhaps Ares . Coins from Solunt were found in many places in Sicily and prove the prosperity of this community.

Excavations

Solunt was identified using ancient sources by the Dominican brother Tommaso Fazello , who published the first printed history of Sicily in 1558. The first excavations took place in 1825 by Domenico Lo Faso Pietrasanta , who published his results in 1841. He excavated a sanctuary and discovered several statues. Systematic excavations were carried out by Francesco Saverio Cavallari since 1856 , after the first chair in archeology had been established at the University of Palermo . A first city map was published in 1875.

Cavalleri's excavations were continued by Antonio Salinas , who also published the first somewhat more detailed reports. Modest excavations were only carried out again in 1920 by Ettore Gábrici, who only uncovered a few rooms within the city. Vincenzo Tusa has been digging since 1951 . He found the theater in 1963, the Casa di Leda in 1953 and the Casa di Arpocrate around 1970 . One reason for the increased excavation was the tourist potential that was seen in the ruins. Complete results of these excavations have not yet been published. Some of the artifacts found (especially coins) are in Palermo in the Regional Archaeological Museum (Museo Archeologico Regionale “Antonio Salinas”), while others are on display in a local museum.

Research by the German Archaeological Institute in Rome had been carried out in the city since 1964 . The architecture of the Agora was recorded under Helmut Schläger , but the results could never be published because of Schläger's early death. Armin Wiegand has been investigating the theater since 1988 and published a study on the building. Markus Wolf dedicated himself to the agora and the houses of the city with a special focus on the Gimnasio . A monograph was published on each. In 2014 Alberto Sposito published an architectural study in which he presented all the excavated buildings and presented an inventory of the remains.

General

The city is located on the eastern slope of Monte Catalfano. There are 60 meters between the highest and lowest point. Solunt is regularly laid out in the form of a chess board according to the Hippodamian system , without taking the uneven terrain into account. The insulae are numbered with modern Roman numerals.

Only the access to the city in the southeast is adapted to the steep terrain. The road winds up the mountain and ends in the so-called Via dell'Agora, the most important street in the city, via which one reaches the agora in the north. It runs roughly at ground level, while the stepped hillside roads that lead from it overcome great differences in altitude. To the west and east there are further main roads at ground level; the eastern one is now called Via degli Ulivi. The western and highest main street is Via degli Artigiani. The main streets are approx. 6 meters wide, the secondary streets 3 meters. The parceling results in blocks of houses measuring around 40 × 80 meters. The blocks each have an alley about one meter wide in the middle that divides them into two parts. Most of the houses had workshops and shops facing the street, especially along Via dell'Agora.

It is uncertain when exactly the city received its Hippodamian city map. Below the theater are the remains of a Punic house that did not follow this plan. This may indicate that the first foundation was rather irregular. Armin Wiegand suspects that Solunt was born with the arrival of Greek soldiers in 307 BC. Was reorganized.

Although the general character of the city is Hellenistic-Roman, there are also many Punic elements. Punic traditions were followed, especially in the religious field. The city did not have a temple in the classical Hellenistic-Roman style, but there were three sanctuaries that are Punic in style. In one of them there was a larger than life statue of Zeus from the Hellenistic period . In another sanctuary, a statue from around 300 BC came. BC to days, which in turn is stylistically clearly a Punic work. Punic traditions were also followed in burial customs with the preference for body burial.

Some houses had small chapels with typically Punic steles . Other Punic elements are the use of Opus africanum in architecture. The walls consisted of a series of pillars as supports, while the spaces in between are filled with loose stones. The round ends of the cisterns are also typically Punic. For the floors in many houses, Opus signinum , a floor plaster , was used that was developed in Carthage in the third century BC and only later gained a foothold in the Roman Empire.

Public facilities

City walls

Due to its favorable location on a steep mountain slope, the city did not need a continuous city wall. There are steep cliffs in the south and west. In the north, the slope has slipped over time and carried away parts of the city. So it remains unclear whether a full-length wall ever stood there. Only the east and north-west sides of the city certainly once had a wall with towers.

Especially on the southeast side of the city, where the only road winds up the mountain, there are remains of defensive structures along the road. For example, the remains of a tower can be made out. There have not yet been any excavations there. Other remains can be found in the far northwest of the city, on the edge of the abyss into which parts of the city once slipped. There are remains of the wall and the remains of a rectangular tower and a large cistern may also have been part of a defensive structure. Next to it an ancient road leads to the highest point of the mountain. Excavations in 1875 in the far east of the city, from where there was a good view of the sea, brought to light an altar and other structures. Perhaps the port of the city should be controlled from here.

Thermal baths

The remains of the thermal baths are in the very south of the city. The small building consists of four larger rooms and a few smaller side rooms. In the far south was an open courtyard, next to it the frigidarium , which was once decorated with a geometric mosaic . The mosaic has completely disappeared today. Further north is the tepidarium with an apse to the west. This is followed by the caldarium and the laconicum . The tepidarium and the caldarium were owned by hypocausts .

In an adjoining room there is a staircase and in a small passage room behind the caldarium there is a colored mosaic with the image of a vase. Remains of Doric columns attest to the more elaborate architectural ornamentation. Parts of the bath on the east side have disappeared because they slid down the steep mountain slope. The thermal baths were built in the first century BC. Built in BC. The geometric mosaic dates back to the first century AD, when the building was partially renovated.

Agora

The agora is an elongated square and was the central place of festivals, meetings and markets in the city. There seems to have been a gate or door at the southern entrance. The remains of a stone threshold and a large six-armed star in the stone pavement were found. The west side occupies a stoa that belongs to the wing risalitstoen type . The building is around 68.70 meters long and 20.30 meters wide. There are two side wings. The whole front is taken up by a portico . Behind it are nine exedra . The Doric columns of the portico have largely disappeared, but numerous components are still preserved. These include ledges made of tufa , which are decorated with lion heads and stylistically dating back to the second century BC. Are to be dated. The second floor was divided by half-columns, between which there was a diamond lattice decoration. This is also attested to on the second floor of the skene of the theater and on the second floor of the peristyle of many private houses. It is a decorative element that is particularly popular in the western Mediterranean. In the northernmost exedra, two Greek inscriptions on two statue plinths name Apollonios and Ariston (father and son), whose statues were obviously there. A first stoa was probably found in the fourth or third century BC. When the city was founded. The preserved remains, however, date from the second century BC.

At the Agora Stoa behind the closed Buleuterion , where the advice of the city met. The room had five rows of seats and seated around 100 people. The function cannot be recognized with certainty. In older literature, the building is also referred to as an Odeon . More recent literature, on the other hand, speaks more of a Buleuterion. Markus Wolf suspects both functions in one building. South of the Buleuterion is a walled area of 31.40 × 12.30 meters, the function of which is unclear. Maybe it was a sacred district.

To the north of the theater are the remains of a high school . The not well-preserved building had a large courtyard, which was surrounded by columns except on the west side. There were two cisterns under the floor. The remains of a large cistern are also located at the agora. It is about 25 × 10 meters in size, has nine rows of pillars and was therefore once roofed. The roof probably covered a free space near the agora. In the north-east of the agora are the very poorly preserved remains of another imperial bath. It can only be recognized by the floors, rising masonry has not been preserved.

theatre

Part of the agora was a theater that was uncovered in 1953 and then completely in 1958. It was probably made in the second century BC. Erected when all of Sicily flourished under Roman rule. In the north it was built over an older residential building. So there seems to have been no previous theater at this point. The theater is built into the slope of Monte Catalfano. Not much has been preserved from its rows of seats. Some stones in the middle part form a modern reconstruction. There used to be a total of around 20 rows of seats.

Only parts of the foundation walls of the Skene have been found. It can partly be reconstructed with components lying around. The building once had an area of about 21.60 × 6.60 m and was two-story. At each end there was a wing ( Paraskenion ). As can be seen from the preserved components, the stage building was divided by doors and Doric columns. On an upper floor, the facade had Ionic columns . Two caryatids may have decorated the base. There were probably parapets with rhombuses on the upper floor. Two construction phases can only be distinguished in the Orchestra . The theater was likely to work until the end of town.

temple

The remains of various temples are in Solunt. None of them follow classical Greek or Roman models. They are more in the Punic tradition, although it is often difficult to find exact parallels in the details.

Behind the Buleuterion and the theater is a temple complex with five shrines, four of which are arranged in pairs; the northern pair is very poorly preserved. In between there is a central shrine. Some shrines have niches at the western end that once housed statues, three statues were found in.

In the southernmost shrine was a larger than life statue depicting either Zeus or Baal. It is now in the Archaeological Museum of Palermo. The statue, discovered by Domenico Lo Faso Pietrasanta in 1826, is 1.65 meters tall and made from local tuff. It's a rough, provincial work by an artist who wasn't untalented. The statue is usually dated to the second half of the second century BC and proves that wealthy citizens who were able to commission and finance such an image still lived in the city at this time.

In the northern shrines there might have been a statue of Hermes and an archaic-looking seated statue depicting Astarte , Tanit or Artemis . This double shrine was also discovered by Domenico Lo Faso Pietrasanta in 1826 and is about 10.40 × 8.60 meters in size. It consists of two cellae with benches on three sides and a courtyard. The whereabouts of the Hermes statue from the southern cella is unknown.

The statue of the goddess from the northern cella also ended up in the Archaeological Museum of Palermo. The figure made of local limestone is badly damaged and shows a goddess seated on a throne flanked by two sphinxes . The seemingly archaic style initially led to the statue being dated to the 6th century BC. It was assumed that the statue adorned a temple in the archaic city and that it was transferred to the new settlement after its destruction. However, recent research has shown that the statue was built in the second half of the fourth or first half of the third century BC. Dated and follows Punic patterns in style and design.

At the entrance to the Agora, on the western side of Via dell'Agora, there is another sanctuary (Insula VIII). It is a large house with an inner courtyard and three rooms on the street front, in the southern part there are still three high, pillar-like altars. The middle room with a large entrance on the street side has stone benches on all sides and has been interpreted as a waiting room. The function of the third, northernmost room cannot be determined with certainty.

Houses

There are two types of houses. Large houses, especially in the city center, had a two-story peristyle . Rather on the outskirts of the city were smaller residential buildings that had no peristyle, but at least had a courtyard. Due to the hillside location of many houses, up to three floors are often preserved.

The two-storey peristyle courtyards are typical of the houses in Solunt, but such peristyle are also known from other parts of northern Sicily. They come from the years shortly after 300 BC. In other parts of the Greek world they appeared later, so that northern Sicily played a special role in the development of residential architecture. The different floors of the houses were often used for very different functions. The shops on the lowest floor of the houses in the center of the city were mostly not connected to the rest of the house, but were used as support structures for the floors above. The first floor often contained the peristyle and other living and state rooms, while the second floor contained utility rooms such as stables and kitchens. The facades of the richer residential buildings were decorated with pilasters and half-columns . Almost all houses had a cistern that was used to collect rainwater for the water supply.

The houses and most of the buildings in the city are made of two types of stone, on the one hand dolomite , a hard, gray stone from the city mountain Monte Catalfano. In addition, a calcareous sandstone was used for building, which came from nearby quarries. Clay mortar was used as a binding agent. Various masonry techniques were used. The most popular was the "ladder masonry". Small, well-hewn sandstone blocks were placed next to large dolomite blocks and the spaces between them were filled with smaller stones. The walls were always double-shelled. Quarry stone masonry was often used, especially for the lower parts . In this masonry technique, dolomite stones of different sizes were put together. Well-hewn stone blocks were used, especially for facades. The technique of Opus africanum was also used in older buildings . The stones were placed between individual pillars. The roofs of the houses were covered with simple terracotta roof tiles.

high school

The grammar school (Italian Ginnasio ) was not a public building, even if the name suggests it (Insula V). During the excavations around 1865, a Greek inscription with a dedication for a high school student was found there. The inscription should not come from the house. The high school is a large residential building with a two-story peristyle . In the 19th century, six columns of the peristyle were erected again and various parts were added.

The house was probably built as early as the third century BC. It was inhabited until the beginning of the third century AD. Several phases of renovation could be determined. The house is on Via dell'Agora, the main street of the city, and thus had a privileged location. There were four shops facing the street, each with two rooms, which were probably sublet.

The Ginnasio is on a steep slope; accordingly, the main floor with the peristyle and various smaller rooms is also the first floor. It also had an entrance through a side street. A second floor has been preserved. It is located at the top of the slope and can be reached by stairs from the peristyle. A separate monograph is dedicated to this house, which primarily examines the architecture of the house.

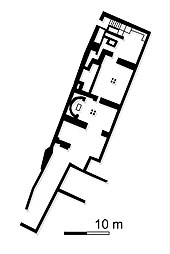

Leda's house

The name of the Casa di Leda (House of Leda; Insula VII) is derived from wall paintings on which Leda is depicted. The house, which is also directly on Via dell'Agora, was excavated by Vincenzo Tusa in 1963. The building is approximately 26.70 × 19.50 meters and has a floor area of approximately 520 m². On the street side there were again four shops, the facade of which has been completely lost. The two outer shutters were wider than the two middle ones. All of them were probably upstairs. Remnants of stairs and various fixtures such as benches have been preserved.

The entrance to the house is in the south on Via Ippoamo da Mileto, a side street. The center of the Casa di Leda was the once two-storey peristyle with four by four Ionic columns, only one of which has been partially preserved. This part of the house is 5.65 meters above the level of the shops. On the east side of the peristyle there is a cistern along the entire length of the courtyard. In the middle is a basin decorated with a geometric mosaic, in which rainwater was collected and from there directed into the cistern. The whole peristyle is decorated with a simple mosaic.

In the center on the west side is the triclinium with relatively well-preserved and high-standing wall paintings on the walls. The dating of these wall paintings is controversial. They were initially dated to the end of the first century AD and therefore belonged to the fourth style . The more recent research prefers a classification in the first century BC. And an assignment to the second style . The wall paintings consist of fields with individual figures in the center, including the depiction of Leda with the swan. The wall painting replaced an original First Style decoration . Wall paintings have also been preserved in other rooms. The floors were partly decorated with geometric mosaics. In a room south of the peristyle there was a mosaic with the oldest representation of an astrolabe and a technical feature. The individual lines in the drawing are separated by strips of lead. The excavator of the house suspects that it is a work from Alexandria . Numerous statues have been found in the house. In a larger room that was accessible from a side street, Via Ippodamo da Mileto , stone feed troughs indicate that the room was used as a stable.

House of Masks

The House of Masks ( Casa delle Maschere , Insula XI) was partially exposed in 1868–1869. It stands at the highest point in the city. The center was the atrium . This was followed to the east by a peristyle. On the east side of the house was a kind of veranda with a view over the city to the sea. In one room of the house there were well-preserved wall paintings in the so-called second style of the first century BC. These paintings of the decoration system also called architectural style show painted wall coverings made of stone slabs. There are painted garlands above, from which theatrical masks hang down. The paintings are now in the Museo Archeologico Regionale Antonino Salinas .

House of Harpocrates

The Casa di Arpocate (House of Harpocrates, Insula VI) got its name from a bronze statue of the Egyptian god Harpocrates found there . The building is about 20.30 / 60 × 17.50 / 21.80 meters in size and thus covers an area of about 404 m². It was uncovered by Vincenzo Tusa around 1970. This house was also built with different levels due to its location on the slope of the mountain. The main entrance was in the north and could be entered from the side street Via Ippodamo da Mileto . The entrance led into a vestibule and from there into a peristyle courtyard with four Doric columns in the basement and four more on a second, reconstructable floor. At 7.30 × 10.10 m, the peristyle is quite small compared to those in other houses in the city. The courtyard was once two-story. Opposite the entrance is the exedra, the main room of the house, which is decorated with a geometric mosaic. The mosaic shows a circle with a meander as a frame. The walls have remains of wall paintings. There is a cistern in a room west of the peristyle. On the east side of the peristyle a staircase to the second floor has been preserved.

House of Garlands

The Casa delle Ghirlande (Insula X) is in the very north of the city, north of the agora and thus beyond most of the other excavated buildings. It has a peristyle courtyard from which additional rooms were accessed. Parts of the building are lost and have fallen victim to erosion. When it was found, the house had well-preserved murals in the late ( Augustan ) Second Style with a row of candelabras with garlands on light backgrounds. In another room there were remains of other paintings in the second style. In this case, marble siding is painted on the wall. These paintings have also faded a lot. Some floors have simple black and white mosaics. In the house there was also a small decorated altar with the symbol of the Punic goddess Tanit . It again proves the mixture of Punic and Roman culture within one house.

Courtyard house

The Casa a Cortile (Insula VII) is a comparatively small house and follows a slightly different plan than the large peristyle houses. This residential building measures around 12/14 × 19.50 meters and takes up around 250 m². The entrance is in the south, on the side street Via Ippodamo da Mileto. From there you get to a large entrance room. To the left is a stable, the stone feed troughs of which have been preserved. To the north of the entrance room is a small courtyard with a single Doric column in the middle. There are more rooms around this courtyard. This house, too, was once two-storeyed, which is particularly evident from the remains of the columns. Despite the limited space in the house, they did not want to do without a column and the prestige that goes with it.

Others

Few buildings can be described as purely commercial. Housing and handicrafts certainly took place everywhere in the city and in the same neighborhoods. Especially in the north-west there were many rather smaller residential buildings, in which perhaps craftsmen lived. The excavator Tusa described the area as a "craft district". Parts of stone flour mills have been found in various houses . In Insula 13 at the highest point in the city are the remains of a building with an open courtyard. There are four rooms to the west of this courtyard. One of them had an oven.

The necropolis

Parts of the necropolis were found during excavations at the foot of Monte Catalfani, very close to today's Santa Flavia train station . The tombs are typically Punic. While cremation predominated among the Greeks, there were mainly body burials. They are burial chambers carved into the rock, which can be entered via a staircase. Long, rectangular niches on the walls and in the floor were intended for the burial of the corpses. Some of the graves date back to the fourth and third centuries BC. Numerous Tanagra figures are particularly noteworthy.

The ruins today

Until 2009, the Parco Archeologico di Solunto , the archaeological site, was closed, which is why visitors had to make do with a tour of the antiquarium. Various settlements and relics are depicted there; there is a description of the architecture and information about the way of life of the city dwellers, such as: B. Burial of the dead, pottery making, fishing. Access to the excavation site has been open to visitors since 2009. In 2014 the Archaeological Park of Solunt had around 10,000 visitors. The nearest train station, Santa Flavia-Solunto-Porticello, on the Palermo-Termini Imerese line , is around 2 km from the park. Like all ruins, maintaining the city is a major conservation challenge. Many paintings that were found in the mid-20th century have faded today. The paintings of the Second Style, discovered in the 19th century, on the other hand, are much better preserved, as they were first protected by the excavation house, then removed from the wall and taken to a museum. The preservation of the stone is also difficult because the local building block is very crumbly.

literature

- Aldina Cutroni-Tusa, Antonella Italia, Daniela Lima, Vincenzo Tusa: Solunto , Itinerari XV, Roma 1994 ISBN 88-240-0310-9

- Alberto Sposito : Solunto: paesaggio, città, architettura. "L'Erma" di Bretschneider, Rome 2014 ISBN 978-88-913089-9-3 .

- Armin Wiegand: The Solunt Theater. Zabern, Mainz 1997 ISBN 978-38-053203-5-1

- Markus Wolf: The houses of Solunt and the Hellenistic residential architecture. Zabern, Mainz 2003, ISBN 3-8053-3267-X .

- Markus Wolf: The Agora of Solunt: Public buildings and public spaces of Hellenism in the Greek west. Zabern, Mainz 2013, ISBN 978-3-89500-726-2 .

- Konrat Ziegler : Solus. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume III A, 1, Stuttgart 1927, Col. 983-985.

Individual evidence

- ^ Ziegler: Solus , in: Paulys Realencyclopädie, 983

- ↑ Thucydides, Peloponnesian War 6,2,6.

- ↑ Wolf: The Houses of Solunt , 1.

- ↑ Chiara Blasetti Fantauzzi, Salvatore DevinCenzo: The Phoenician colonization in Sicily and Sardinia and the problem of the emergence of power in Carthage. In: Kölner and Bonner Archaeologica 2, 2012, p. 18.

- ↑ Diodor , Bibliothéke historiké 14,48,4–5; 14.78.7.

- ↑ Roger Wilson JA : Ciceroan Sicily. In: Christopher John Smith, John Serrati (eds.): Sicily from Aeneas to Augustus. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2000, ISBN 0-7486-1367-6 , p. 137.

- ↑ Wolf: The Agora of Solunt , 45.

- ^ Alba Maria Gabriella Calascibetta, Laura Di Leonardo: Un nuovo documento epigrafico da Solunto. In: Carmine Ampolo (ed.): Sicilia occidentale. Studi, rassegne, ricerche. Pisa 2012, pp. 37-48.

- ↑ Cutroni-Tusam in: Cutroni-Tusa, Italia, Lima, Tusa: Solunto , pp 16-21

- ↑ Wolf: The Houses of Solunt , 2.

- ^ Domenico Lo Faso Pietrasanta: Le antichità della Sicilia. Volume 5: Antichità di Catana - Palermo . 1842, pp. 57-67, plates 38-41.

- ^ Wiegand: The theater of Solunt .

- ↑ Wolf: The Agora of Solunt .

- ↑ Wolf: The houses of Solunt .

- ^ Sposito: Solunto .

- ^ Wiegand: Das Theater von Solunt , p. 29.

- ^ Roger JA Wilson: Hellenistic Sicily, 270-100 BC. In: Jonathan RW Prag, Josephine Crawley (Ed.): The Hellenistic West: Rethinking the Ancient Mediterranean. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2013, ISBN 978-1-107-03242-2 , pp. 114-116.

- ↑ Italia, in: A. Cutroni Tisa, A. Italia, D. Lima, V. Tusa: Solunto , pp. 36-39

- ↑ Sposito: Solunto , 101–110

- ↑ Italia, in: Cutroni Tisa, Italia, Lima, Tusa: Solunto, p 70; Image of the star: Parco archeologico di Solunto

- ↑ A monograph is dedicated to the Stoa: Wolf: The Agora of Solunt ; on the diamond grids: Wiegand: Das Theater von Solunt , p. 53.

- ↑ Wolf: The Agora of Solunt , 45

- ^ Wolf: The Agora of Solunt , 41

- ^ Wolf: The Agora of Solunt , pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Wolf: The Agora of Solunt , pp. 24-25

- ↑ Sposito: Solunto , pp. 211-219.

- ↑ Sposito: Solunto , pp. 320–322

- ↑ Wolf: The Agora of Solunt , pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Wolf: The Agora of Solunt , 26

- ^ Wiegand: Das Theater von Solunt , p. 5

- ^ Wiegand: Das Theater von Solunt , p. 20.

- ^ Wiegand: Das Theater von Solunt , p. 29.

- ^ Roger JA Wilson: Hellenistic Sicily, 270-100 BC. In: Jonathan RW Prag, Josephine Crawley (Ed.): The Hellenistic West: Rethinking the Ancient Mediterranean. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2013, ISBN 978-1-107-03242-2 , p. 115, Fig. 4.24.

- ↑ Roger Wilson JA: Ciceroan Sicily. In: Christopher John Smith, John Serrati (eds.): Sicily from Aeneas to Augustus. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2000, ISBN 0-7486-1367-6 , Fig. 11. 15.

- ^ Domenico Lo Faso Pietrasanta: Le antichità della Sicilia. Volume 5: Antichità di Catana - Palermo . 1842, plates 38–41.

- ↑ Nicola Chiarenza: On Oriental Persistence in the Hellenic Town of Soluntum: a New Hypothesis about the Statue of an Enthroned Goddess , in: L. Bombardieri, A. D'Agostino, G. Guarducci, V. Orsi and S. Valentini (eds .) SOMA 2012, Identity and Connectivity, Proceedings of the 16th Symposium on Mediterranean Archeology, Florence, Italy, 1-3 March 2012 , BAR International Series 2581 (II) 2013. Oxford 2013, ISBN 9781407312057 , pp. 945-954.

- ↑ Sposito: Solunto , pp. 197-200.

- ↑ Wolf: The Houses of Solunt , 101.

- Jump up ↑ Wolf: The Houses of Solunt , 111.

- ^ Wolf: The houses of Solunt 6-8

- ↑ Wolf: The Houses of Solunt , 53-61.

- ↑ Wolf: The Houses of Solunt , 64-69.

- ^ Sposito: Solunto , 235

- ↑ Hendrik Gerard Beyen: The Pompeian wall decoration from the second to the fourth style. Volume 1. Haag 1938, pp. 44-46; for modern restorations and reconstructions, see: Il reauro dei dipinti di Solunto .

- ↑ Wolf: The Houses of Solunt , 53-61.

- ^ Mariette De Vos: Pitture e mosaico a Solunto. In: Bulletin Antieke Beschaving. Volume 50, 1975, pp. 195-224, Figs. 24-25.

- ^ Sposito: Solunto , pp. 220-227.

- ^ Italia, in: A. Cutroni Tisa, A. Italia, D. Lima, V. Tusa: Solunto , p. 81

- ↑ Wolf: The Houses of Solunt , 68-71.

- ^ Sposito: Solunto , 191, 196, figs. 34, 16.

- ↑ Sposito: Solunto , pp. 236-250.

- ^ V. Tusa, in: A. Cutroni Tusa, A. Italia, D. Lima, V. Tusa: Solunto , pp. 162-163.

- ↑ Aumentati i visitatori nel parco archeologico di Solunto anche grazie al Jazz

- ↑ A. Sposito e AA.VV., Morgantina e Solunto. Analisi e problemi conservativi , Palermo 2001.

Web links

- Solous, Soluntum, Sicily on Arachne

- Description of the Archaeological Park of Solunto (Italian)

- Articles in Princeton encyclopedia of ancient sites (English)

Coordinates: 38 ° 5 ′ 35 ″ N , 13 ° 31 ′ 53 ″ E