Teletext

Under teletext , in Germany Teletext called, refers to a form of communication to disseminate messages, texts and pictorial representations for analog transmission in the blanking interval of the television signal of a television broadcast and from which the user desired information for display on the screen of a television can choose. With today's digital ( DVB ) transmission, the digital teletext signal is embedded directly as an additional stream in the MPEG-TS container. DVB receivers can modulate these back into the blanking interval of an analog signal for display on old TV sets.

Transmission and Practice

An analog television picture according to the Central European television standard has 625 picture lines. Of these, only 576 lines are used for the transmission of a picture content, the rest being the blanking interval during which the television set prepares to receive the next picture. In the early 1970s, British television technicians from the BBC came up with the idea of broadcasting additional information in this unused area. This resulted in the first specification of the U. K. Teletext Standard in 1974 . Its text data are organized on a page-by-page basis and offer space for 25 lines of 40 characters each (23 lines can be freely edited, the others are reserved for headers and footers). The pages can be designed with 96 different letters, numbers and special characters as well as 128 graphic characters. This corresponds to the state of the art at the time of the introduction of teletext. The background can usually be switched between opaque (for better readability) and transparent (for following the program). Each table is assigned a language that is coded in 3 bits and basically covers all Western European languages by means of character replacement according to ISO 646 . In addition, there was teletext with Cyrillic script in the Soviet Union and Arabic script in the Middle East .

Older televisions build each page individually from the data stream, which can lead to long waiting times. Since not all pages are coded simultaneously in the blanking interval , these devices have to wait until the requested page is broadcast. In spite of the small volume of data in the early days of the teletext system, the page memories commonly used in television sets were too expensive from the manufacturer's point of view. In older devices, individual pages could be determined which should be saved in the page memory and were therefore available more quickly. In the case of simple decoders, this was always the current next page by default and often magazine pages 100, 200, 300 ... However, as the prices for memory chips have fallen sharply these days , current devices usually have a memory with a size of ten to more than 2000 pages ( marketed under terms such as MegaText or TOP-Text ), from which the desired page can be called up.

Although Teletext can only have page numbers from 100–899 ( coding see below), a memory of more than 800 pages makes sense: These memories can also store the sub-pages of individual panels (ie complete "scrolling pages").

Although the teletext is always transmitted with the current television picture, recording the text with the program with analog video recorders (VHS) was usually hardly possible due to the insufficient bandwidth , S-VHS or professional systems (e.g. Betacam SP ) required. Programs recorded with the PC under Windows in .wtv format contain the entire teletext data of the respective channel at the time of recording.

Lines 7–15, 20–21 in the 1st field and 320–328, 333–334 in the 2nd field are used for transmission.

Character sets

The character sets defined in ETSI EN 300 706 of the teletext standard used in Europe are described on the Teletext character sets (ETSI EN 300 706) page .

addressing

The individual pages or panels are selected using a three-digit code . The first digit of the page number, the so-called magazine, is coded with 3 bits and can only have the values 1–8 (0 is interpreted as 8), the second and third digits are coded with 4 bits, which means that hexadecimal numbers are also possible. which cannot be called up with normal televisions. However, addresses such as 1F6 or 8AA are sometimes used for test pages, control pages for the TOP text, or fee-based teletext offers .

The pages are transferred one after the other in an endless loop , the so-called carousel; Since only a small amount of data fits into each individual blanking interval, it takes a while after a page has been selected before it is sent again. The main page 100 (and often also the other magazine pages 200, 300, ...) are very often fed into the carousel, so that this page is displayed very quickly. The selected page is saved in the receiver so that it can be viewed in peace. Sub-panels of scrolling pages are repeated at a fixed time interval (i.e. more frequently in the case of extensive text offers). Today's televisions have enough memory in which many (typically 10 to 2000) or all pages, sometimes even sub-pages, can be stored at the same time. These are then immediately available when selected. Only after changing channels does it still take some time (one to two minutes) until the pages of the new channel are saved.

Page occupancy

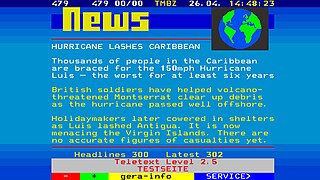

The content of the teletext is mostly program-related additional information, the television program or news . Many private broadcasters also send advertisements , mainly for telephone hotlines that are subject to a charge, competitions or erotic offers. Occasional experiments were also carried out with interactive teletext pages, where a caller could, for example, post classifieds via a touch-tone telephone , but the importance of these offers has declined due to the Internet. By contrast, SMS -based interactive offers (SMS chat , including classified ads) are now quite widespread among German private broadcasters.

For the German, Austrian and Swiss full programs ( Das Erste , ZDF , RTL , Sat.1 , ProSieben , VOX , Kabel eins , RTL II , ORF eins , ORF 2 , ORF III , ORF SPORT + , SRF 1 , SRF Zwei , SRF info and 3+ ) results in the following breakdown of the content:

- Page 100 is the start page

- Page 101 ff. News ( Swiss radio and television : Page 110 ff.)

- Page 200 ff. Sports (Swiss radio and television: Page 180 ff.)

- Page 300 ff. TV program

- Page 333 Name of the program currently being broadcast (transparent)

In addition, depending on the broadcaster (especially in the public service), other news on special topics is offered on other pages, e.g. B. Science, health, nature, economics, stock prices and prominews. In addition, there is information accompanying the program for reading, tips, arrival and departure times at airports, congestion forecasts, world clock, in the third programs also traffic news, etc.

Pages can consist of several sub-pages that are transmitted and displayed one after the other. Such pages can be recognized by markings such as 1/2 (first of two subpages).

Almost every teletext service sends a test image with the available character set and a display of letters in double height, flashing text and hidden information (puzzle button) as well as another page, the clock cracker test page, which is displayed correctly if the clock frequency is correct of the decoder is synchronous with the television picture. If the clock cracker is not displayed correctly, the decoder is running too fast or too slow and has to be readjusted.

Some stations also broadcast subtitles for the hearing impaired on certain programs via teletext. These then contain the dialogues of the people and describe important noises. The subtitles can usually be found on pages 777 (ZDF, ORF, SRF), 149 (private broadcasters) or 150 (Das Erste undIII).

- Use of teletext for program information

Most teletext services offer a program preview for the next few days, some also for several channels. Many broadcasters have a board that shows what is currently being broadcast and what is coming next. A small text field is shown in the picture so that you can continue to follow the current TV program. Table 333 is usually used for this on German-speaking channels. Because the teletext is constantly updated by an editorial office, program changes usually appear immediately there.

Even at sporting events such as B. football matches, the current results are shown in a corner of the screen without obscuring the rest of the picture.

Ease of use improvements

TOP (Table Of Pages)

The TOP text system ( Table Of Pages ) was introduced in Germany to make it easier to use . Via data on special control pages, the individual panels are divided into categories, so-called blocks for a higher hierarchical level (e.g. news, sport, program) and groups below (e.g. domestic / international, football / tennis). Abbreviations can be assigned to the pages, which are displayed in color in a 25th line and which can be selected with four colored buttons on the remote control. In addition, information is transmitted which pages exist and which have sub-pages, with the help of which the decoder generates line 25 or z. B. can also indicate that a selected page does not exist.

FLOF (Full Level One Facilities)

With the FLOF system ( Full Level One Facilities ), also called FasText , the 25th line with the names, representation and numbers of the jump destinations can be transmitted separately with each page. This gives the editors the opportunity to create these references on up to four pages themselves and to direct the reader to e.g. B. to manage related topics (or advertising pages, etc.). There is no information on which pages exist or have subpages at FLOF. Also, unlike TOP, the information belonging to the respective page is only displayed in the 25th line when the selected page is found, and not when the page number is entered as with TOP.

Most decoders now support both and use almost all teletext services of one of the systems - in Germany most of the TOP, in other countries more often FLOF.

Level 1.5

With level 1.5 character substitutions are introduced. A kind of list of replacements is transmitted for each page, with one character being replaced by another character at a certain point on the original page. A decoder that only supports level 1 ignores the replacements and only displays the content of the original page.

In addition to the existing 96 text and 128 graphic characters (G0 or G1 character set), 80 new text and 92 additional graphic characters are available as “replacement characters” (G2 and G3 character set). Character combinations are also possible in which one of the 96 previous text characters is overlaid with one of 16 diacritical characters .

Level 2.5 (HiText)

Another downward compatible extension of the teletext standard with the designation Level 2.5 or HiText allows u. a. the free definition of 16 colors, extended special characters and formatting as well as the free definition of your own characters, which enables higher-resolution graphics. However, this extension is only offered by a few teletext services and is not supported by decoders of many simple devices. Usually HiText is only used for your own station logo. The disadvantage is that the downward compatibility requires the transfer of the graphic in both resolutions and thus increases the data requirement.

providers

Current users of HiText in the German-speaking area are

- ZDF

- BR television

- 3 sat

- Phoenix

- Thuringian media education center of the TLM in Gera (colored backgrounds, graphic extensions with G3 characters and test pages 460 to 499)

The ARD , the NDR , the SWR , arte and ProSieben have carried out tests or the time was limited. BR television introduced it in 1999 as the first institution within ARD, but according to its own information it ended in 2005 and finally reintroduced in 2011.

Outside of the German-speaking area, level 2.5 is used by France 3 (station logo, background color) and NOS text in the Netherlands (background, as well as test page 389).

Level 3.5

The teletext standard ETSI EN 300 706 defines a further level 3.5 (with colored high-resolution graphics, proportional font, etc.), which is hardly supported by decoders or services.

Further ease of use

At the decoder / television / remote control level, there are a number of functions that facilitate operation:

- changed display of color

- Larger font by doubling the line height ("half" pages)

- targeted selection of a subpage

- so-called page caching makes it possible to follow the page numbers shown in the text like a link: The system recognizes them by three consecutive digits; These can be selected using the buttons on the remote control, and the decoder selects this page number by pressing the OK button.

Individual countries

Germany

During the radio exhibition in 1977 in Berlin, teletext / videotext was presented by ARD and ZDF for the first time with a 400-page offer. With the radio exhibition in 1979, the nationwide test operation of the ARD / ZDF teletext editorial office, located at the SFB in Berlin, began under the direction of Alexander Kulpok, to whom the directors of ARD and ZDF had assigned this function. In 1980 the teletext service of the public broadcasters was brought into regular operation. Under the name ARD / ZDF-Videotext-Zentrale, this joint facility of the two public law systems continued to be located at the Sender Freies Berlin until the separation of ARD and ZDF in 2000. The term “teletext”, which often led to confusion with the Swiss Post's teletext service, was defined in the Federal Republic of Germany by the Commission for the Expansion of the Technical Communication System (KtK) chaired by Prof. Eberhard Witte (1928-2016) . Up until the year 2000, the ARD / ZDF teletext headquarters belonged to the decisive group of teletext pioneers in the European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Its head, Alexander Kulpok, was appointed EBU teletext coordinator in Geneva. Under his chairmanship, an EBU working group with representatives from Great Britain, Norway, the Netherlands and the Federal Republic u. a. in 1996 the Electronic Program Guide (EPG) - the program guide that became an integral part of all television programming. The range of subtitles for the hearing impaired initially began with the 8 p.m. Tagesschau and was continuously expanded to include sports broadcasts and feature films in international cooperation.

Regular operations from 1980 onwards gave the SFB a useful international reputation as a state broadcaster in divided Berlin. In 2000, ARD and ZDF separated to start two independent offers. Since then, the SFB has been responsible for the ARD text. After the merger of the broadcasters SFB and Ostdeutscher Rundfunk Brandenburg (ORB), most of the content is processed by Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (RBB) from Potsdam. The current political content of the ARD text is edited by the Tagesschau.de editorial team at Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR) in Hamburg.

Almost all regional and national programs now have their own teletext services. In the Federal Republic of Germany, the WDR began very soon after the introduction of teletext as a regular service.

In 2010, the teletext of ARD, ARD-Text, had the largest market share with 18.6%, ahead of ZDF, ZDF-Text, with 14.8% and that of RTL with 13.4% market share.

From August 16, 2012, a month-long International Teletext Art Festival took place on ARD's teletext.

18 editors work for the ARD text. According to the broadcaster, the operation costs around 1.7 million euros per year. With a market share of 11 percent, RTL is the provider with the highest ratings among private broadcasters.

In addition to Teletext, ARD has been delivering the new Hybrid Broadcast Broadband TV standard , or HbbTV for short, since 2008 . This system offers significantly more options than teletext, among other things, radio and Internet content can be linked to it.

Teletwitter is offered for programs such as Tatort , football matches or the Eurovision Song Contest . Using this new format, comments from Twitter are fed into the teletext after editorial approval.

In 2013, GfK counted almost 44 million different visitors in the ARD text. Every day, 12.37 million viewers use various teletext offers; in 2016 it was still accessed daily by 10.4 million users.

France

In France, a graphically elaborate standard called Antiope had been developed, but it was never widespread and was later replaced by Teletext.

United Kingdom

After attempts from 1972 onwards, Ceefax was the first teletext system in the world to be launched in the United Kingdom on September 23, 1974 , initially in black and white, before the UK Teletext Standard also made different font colors possible. Ceefax director Colin McIntyre (1924–2012) is regarded as the father of the teletext philosophy, which focuses on clarity and topicality. Ceefax was phased out in 2012 as part of the switch to digital transmission technology. Unlike in Germany, no classic teletext is transmitted via digital channels. Instead, the BBC Red Button is offered there, which is more based on an interactive, multimedia program guide.

Sweden

As the first broadcaster outside the UK, SVT began teletext trial broadcasts in Sweden on March 12, 1979.

Austria

The third broadcaster in Europe with teletext was followed by ORF in Austria on January 21, 1980. Before that, on January 21, 1980, Gerhard Weis , then head of the “Public Relations, Coordination and Corporate Planning” department, read a report in the Times about the BBC's first attempts that have been running since the late 1970s. Their device could display 64 stored pages and has now been replaced by a new device with 200 possible pages. The old system was bought by the ORF and from July 9th there were “samples” every half hour during the day on FS 1 and FS 2 until the second phase started in December with an offer expanded to 200 pages. At that time there were only around 500 teletext-compatible devices. In 2014 there were more than 1,400 pages and around two thirds of the broadcasts on ORF one and ORF 2 were subtitled on page 777. The offer is used by around 1.9 million readers per week and an average of around 18.4 million pages are accessed per day.

Teletext from various private broadcasters in Austria was often criticized because it was not designed to be suitable for young people, the information was suppressed by advertising and “only represents a platform for advertisements and advertising”.

Structure of the ORF teletext

Since March 16, 2009, the ORF teletext has a new design. The regional news from the state studios can now also be called up. The ORF teletext is divided into various categories, including "Sport", "Politics", "Chronicle" and "Program Information" as well as "Culture and Show", "Multimedia", "Health", "Travel", "Games and Stars" "And" Help ". Another focus of ORF TELETEXT's content is the service information that is also offered and has been made available by cooperation partners for several years. The services range from weather information and continuously updated stock exchange and market data on departures and arrivals at airports and arrivals and departures at train stations. Traffic information or emergency service phone numbers are also listed. The ORF teletext can also be queried over the Internet.

Switzerland

The SRF teletext (then DRS and SF1, SF2) was broadcast for the first time on October 1, 1981. Half of the initially 64 pages were provided by SRG and Videopress, an association of ten newspaper publishers: Videopress was responsible for news and business, and SRG for sport and entertainment. The broadcast was from 10 a.m. until the end of TV RS broadcast. It has been broadcast in French-speaking Switzerland since 1985 and in Italian since 1986. Interactive teletext services have been offered since 1994. Swiss Teletext offered NexTView between 1997 and 2013. In 2001 an average daily number of visitors of 1.17 million was reached, in 2004 of 1.3 million. Although new media such as the Internet emerged, the record usage was during the Turin 2006 Olympics.

The teletext of Swiss television (since 2011 Swiss radio and television ) can also be queried via the Internet.

United States

In the United States, various experiments were made with teletext as early as the late 1970s. But when in 1990 a special subtitle decoder for the hearing impaired was required by law in every new television set, the manufacturers decided not to install an additional general teletext decoder. As a result, there is practically no teletext broadcast there today.

Russia

Teletext was used in the Soviet Union from the mid-1980s. However, not for private use, but for the internal exchange of messages within the state news agency TASS , since the televisions made in the Soviet Union for home use did not have a decoder for teletext.

Teletext did not gain a foothold in Russia until after the collapse of the Soviet Union , but it was nowhere near as widespread as in Western European countries. In 1994, the then Moscow local broadcaster “31 kanal” was the first broadcaster to introduce teletext. The channels Perwy kanal , TWZ and REN TV currently have teletext. On the channels Rossija 1 , Rossija K and NTW , the teletext is only used to generate subtitles for some programs. Some broadcasters, such as MTV Rossija , have now abolished teletext.

Archiving

Many providers do not maintain a complete archive of broadcast teletext content. For example, the British providers BBC and Teletext Ltd. not to routinely save every page produced. Often, pages were simply overwritten with new content in the respective system without saving the old content. For example, the BBC archives only contain a limited number of screenshots and other materials, mainly from the early days of Ceefax and the late 1990s. Additional content was retained, for example, through recordings of the program “Pages from Ceefax”, during which BBC One and BBC Two broadcast recordings from their own teletext during the nightly broadcast break.

However, many fragments of old teletext content have been preserved to this day, as parts of the teletext broadcast were also recorded in VHS recordings. However, since VHS technology only saved programs in a reduced quality, only parts of the teletext content that was also broadcast were saved. Other formats that were better suited for storing teletext content, such as S-VHS, were not as popular.

However, British programmers succeeded in reconstructing old teletext content using VHS recordings. For this purpose, the recordings were digitized, the teletext signals were extracted and several fragmented versions of the same page were compared using algorithms developed for this purpose in order to restore the original content as accurately as possible.

Related services

Various other data can also be transmitted during the blanking interval , such as VPS signal, data (e.g. channel video data ), music or videos.

With digital television, especially made possible by the DVB standard MHP , content that is more sophisticated in terms of graphics and content is possible than with teletext, which is technically outdated. At the moment, however, most broadcasters are still adopting the teletext content for their digital programs in order to relieve the editorial staff. With digital television, the program information can also be called up via the electronic program guide (EPG).

Sometimes Teletext is confused with on- screen text ( Btx) because of the name , which was also due to the fact that Btx was called Videotex in Switzerland (without the t at the end). Teletex, on the other hand, is a further developed form of telex.

literature

- Jae-Hyeon An: Remote reading on the rise. Forms, contents and functions of teletext . (= Media & Communication; Vol. 26). Lit, Münster 1997, ISBN 3-8258-3602-9 (also dissertation, University of Münster 1997).

- Michael Faatz: On the specifics of the television text. An investigation into content, forms of presentation and perspectives; shown on the basis of the MDR text and the Sat.1 text. Teiresias, Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-934305-32-6 . (= Television science; vol. 4)

- Eberhard König: The teletexts. Attempt of a constitutional classification. Beck Verlag, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-406-07630-0 . (Series of publications by the Institute for Broadcasting Law at the University of Cologne, Vol. 30)

- Maximilian v. Münch: The inclusion of general terms and conditions in television marketing. In: MMR 2006. pp. 202-206.

- Ferdinand Schmatz: The distant text and the addiction . In: Thomas Keul (ed.): Unworthy readings. What authors read secretly. SchirmerGraf, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-86555-053-8 , pp. 78-86. (first published in: Volltext, issue October 2004).

- Wieland Bosman: Private job placement through teletext? In: NZA 1986. pp. 14-16.

- Walter Fischer: Digital television and radio technology in theory and practice. MPEG baseband coding, DVB, DAB, ATSC, ISDB-T transmission technology, measurement technology . 2nd edition, Springer 2009, ISBN 978-3-540-88187-2 .

- Boris Fuchs: The short life of the bearer of hope Btx. In: German printer. No. 20/2007, pp. 41-43.

- Reiner Hochstein: Teleservices, media services and the concept of broadcasting - comments on the practical delimitation of multimedia manifestations. In: NJW 1997. pp. 2977-2981.

- Guido Schneider: Teletext remains in the niche. In: horizon . 37/2005, p. 121.

- Karsten Zunke: On the short wave. In: acquisa . Issue 02/2010, pp. 30–31.

Web links

- 40 years of Teletext - ARD, 2020

- Description of the format at BBC2 and Channel 4 - pdc.ro.nu (English)

- EN 300 706 Enhanced Teletext specification, 2003, ETSI (PDF file; 1.0 MB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bosman, NZA 1986, 14, 15.

- ↑ Fischer, p. 172.

- ↑ Professional video technology: basics, film technology, television technology, devices ... by Ulrich Schmidt, p. 231, ISBN 978-3-642-02506-8

- ↑ Zunke, acquisa issue 02/2010, p. 31.

- ↑ Schneider, HORIZONT 37/2005, p. 121.

- ↑ Chronicle of the ARD, year 1999 http://web.ard.de/ard-chronik/index/4364?year=1999

- ↑ Teletext of BR television (Bayerntext), Plate 198, accessed on August 25, 2010

- ↑ http://www.br-online.de/content/cms/Universalseite/2010/09/03/cumulus/BR-online-Publikation-ab-01-2010--203259-20100903154358.pdf

- ↑ Teletext usage is increasing. at: heise.de January 11, 2011, accessed on January 11, 2011

- ↑ Report at Digitalfernsehen.de , accessed on August 13, 2012

- ↑ What is Teletwitter actually? In: ARD.DE , accessed on February 12, 2018.

- ↑ Why teletext can't be killed. In: Wiwo online. August 23, 2014, accessed February 12, 2018.

- ↑ Why teletext is still loved today. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Welt online . August 31, 2016, accessed November 4, 2016.

- ^ Henry Steinbock: 35 years of ORF Teletext. In: ooe.ORF.at. January 16, 2015, accessed January 17, 2015 .

- ↑ ORF Customer Service - Technology ( Memento from March 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c James O Malley: The Teletext Salvagers: How VHS is bringing teletext back from the dead. In: Alphr. March 7, 2016, accessed April 11, 2016 .

- ↑ Fischer, p. 171.