Education in the United States: Difference between revisions

| Line 393: | Line 393: | ||

* [http://www.high-schools.com/ High Schools Directory] |

* [http://www.high-schools.com/ High Schools Directory] |

||

* [http://www.heartland.org/Article.cfm?artId=10211 The Heartland Institutes' School Reform Issue Suite] |

* [http://www.heartland.org/Article.cfm?artId=10211 The Heartland Institutes' School Reform Issue Suite] |

||

* [http://www.independent529plan.org] |

* [http://www.independent529plan.org Independent 529 Plan] |

||

[[Category:Education in the United States|*]] |

[[Category:Education in the United States|*]] |

||

Revision as of 14:57, 1 May 2007

| |

| U.S. Department of Education | |

|---|---|

| Secretary Deputy Secretary | Margaret Spellings Raymond Simon |

| National education budget (2007) | |

| Budget | $1.14 trillion (public and private, all levels)[1] |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | English; some Spanish |

| System type | Federal, state, private |

| Established Activated | October 17, 1979 May 4, 1980 |

| Literacy (2003) | |

| Total | 97 |

| Male | 97 |

| Female | 97 |

| Enrollment | |

| Total | 76.6 million |

| Primary | 37.9 million1 |

| Secondary | 16.4 million |

| Post secondary | 17.5 million 2 |

| Attainment | |

| Secondary diploma | 85% |

| Post-secondary diploma | 27% |

| 1Includes kindergarten 2Includes graduate school | |

Education in the United States is provided mainly by government, with control and funding coming from three levels: federal, state, and local. At the elementary and secondary school levels, curricula, funding, teaching, and other policies are set through locally elected school boards with jurisdiction over school districts. School districts are usually separate from other local jurisdictions, with independent officials and budgets. Educational standards and standardized testing decisions are usually made by state governments.

People are required to attend school until the age of 16-18 depending on the state. Many more states now require people to attend school until the age of 18. Some states have exemptions for those 14-18. Students may attend public, private, or home schools. In most public and private schools, education is divided into three levels: elementary school, junior high school, and senior high school. Grade levels in each vary from area to area.

The United Nations assigned an Education Index of 99.9 to the United States, ranking it number 1 in the world, a position it shares with about 20 other nations.[1] 76.6 million students were enrolled in K16 study. Of these, 72 percent aged 12 to 17 were judged academically "on track" for their age (enrolled in school at or above grade level). Of those enrolled in compulsory education, 5.2 million (10.4 percent) were attending private schools. Among the country's adult population, over 85 percent have completed high school and 27 percent have received a bachelor's degree or higher. The average salary for college graduates is $45,400, exceeding the national average by more than $10,000, according to a 2002 study by the U.S. Census Bureau.[2]

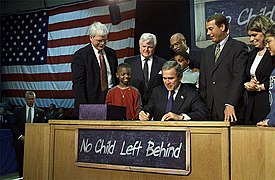

The country has a reading literacy rate at 98% of the population over age 15,[3] while ranking below average in science and mathematics understanding.[4] The poor performance has pushed public and private efforts such as the No Child Left Behind Act. In addition, the ratio of college-educated adults entering the workforce to general population (33%) is slightly below the mean of other developed countries (35%)[5] and rate of participation of the labor force in continuing education is high.[6] However, a recent study showed that "A slightly higher proportion of American adults qualify as scientifically literate than European or Japanese adults". [2]

School grades

The U.S. uses ordinal numbers for naming grades, unlike Canada, Australia, and England where cardinal numbers are preferred. Thus, when asked what grade they are in, typical American children are more likely to say "first grade" rather than "Grade 1". Typical ages and grade groupings in public and private schools may be found through the U.S. Department of Education. [7] Many different variations exist across the country.

Grading scale

Questions about grading scales surface on ISED-L, the Independent School Educators List, from time to time. Although grading scales usually differ from school to school, the grade scale which seems to be most common is this one:

| A | B | C | D | E or F | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | |||||

| 100-96 | 95-92 | 91-90 | 89-87 | 86-82 | 81-80 | 79-76 | 75-72 | 71-70 | 69-66 | 65-62 | 61-60 | Below 60 |

Preschool

| Post Doctorate | PD |

| Doctorate | Q4 |

| Q3 | |

| Master's degree | G2 |

| G1 | |

| Bachelor's degree | T4 |

| T3 | |

| T2 | |

| T1 | |

| High School Ages 14-18 |

H12 (senior) |

| H11 (junior) | |

| H10 (sophomore) | |

| H9 (freshman) | |

| Middle School Ages 11-14 |

M8 |

| M7 | |

| M6 | |

| Elementary School Ages 6-11 |

E5 |

| E4 | |

| E3 | |

| E2 | |

| E1 | |

| Kindergarten Ages 5-6 |

K |

| Pre-Kindergarten Ages <5 |

P/P0 |

| Post-secondary | |

| K-12 | |

| Preschool | |

There are no mandatory public preschool/prekindergarten or crèche programs in the United States. The federal government funds the Head Start preschool program for children of low-income families, but most families are on their own with regard to finding a preschool or childcare.

In the large cities, there are sometimes upper-class preschools catering to the children of the wealthy. Because some upper-class families see these schools as the first step toward the Ivy League, there are even counselors who specialize in assisting parents and their toddlers through the preschool admissions process.[8]

Elementary and secondary education

Schooling is compulsory for all people in the United States, but the age range for which school attendance is required varies from state to state. Most people begin elementary education with first grade (usually five to seven years old) and finish secondary education with twelfth grade (usually eighteen years old). Mandatory education starts with first grade. In some cases, people may be promoted beyond the next regular grade. Some states allow students to leave school at age 16 or 17 with parental permission, before finishing secondary school; other states require students to stay in school until age 18.[9]

Most parents send their children to either a public or private institution. According to government data, one-tenth of students are enrolled in private schools. Approximately 85% of students enter the public schools,[2] largely because they are "free" (tax burdens by school districts vary from area to area). Most students attend school for around six hours per day, and usually anywhere from 175 to 185 days per year. Most schools have a summer break period for about two and half months from June through August. This break is much longer than in many other nations. Originally, "summer vacation," as it is colloquially called, allowed students to participate in the harvest period during the summer. However, this is now relatively unnecessary and remains largely by tradition; it also has immense popular support.

Parents may also choose to educate their own children at home; 1.7% of children are educated in this manner.[2] Proponents of home education invoke parental responsibility and the classical liberal arguments for personal freedom from government intrusion. Few proponents advocate that homeschooling should be the dominant educational policy. Most homeschooling advocates are wary of the established educational institutions for various reasons. Some are religious conservatives who see nonreligious education as contrary to their moral or religious systems. Others feel that they can more effectively tailor a curriculum to suit an individual student’s academic strengths and weaknesses, especially those with singular needs or disabilities. Still others feel that the negative social pressures of schools (such as bullying, drugs, crime, and other school-related problems) are detrimental to a child’s proper development. Parents often form groups to help each other in the homeschooling process, and may even assign classes to different parents, similar to public and private schools.

Opposition to homeschooling comes from varied sources, including teachers' organizations and school districts. The National Education Association, the largest labor union in the United States, has been particularly vocal in the past.[10] Opponents' stated concerns fall into several broad categories, including fears of poor academic quality, loss of income for the schools, and religious or social extremism, or lack of socialization with others. At this time, over half of states have oversight into monitoring or measuring the academic progress of home schooled students, with all but ten requiring some form of notification to the state.[11]

Elementary school

Elementary school, also known as grade school or grammar school, is a school of the first six grades (sometimes, first eight grades), where basic subjects are taught. Sometimes it includes kindergarten as well. Elementary school provides a common daily routine for all students except the most disadvantaged (those having singular needs or disabilities). Students do not choose a course structure and often remain in one or two classrooms throughout the school day, with the exceptions of physical education ("P.E." or "gym"), music, and/or art classes.

Typically, curriculum within public elementary education is determined by individual school districts. The school district selects curriculum guides and textbooks that are reflective of a state's learning standards and benchmarks for a given grade level.[3] Learning Standards are the goals by which states and school districts must meet AYP or adequate yearly progress as mandatated by No Child Left Behind. This description of school governance is simplistic at best, however, and school systems vary widely not only in the way curricular decisions are made but in how teaching and learning takes place. Some states and/or school districts impose more top-down mandates than others. In many schools, teachers play a significant role in curriculum design and there are few top-down mandates. Curricular decisions within private schools are made differently than in public schools and in most cases without consideration for NCLB.

Public Elementary School teachers typically instruct between twenty and thirty students of diverse learning needs. A typical classroom will include children with identified special needs as listed in Individuals with Disabilities Act IDEA to those that are cognitively, athletically or artistically gifted. At times an individual school district identifies areas of need within the curriculum. Teachers and advisory administrators form committees to develop supplemental materials to support learning for diverse learners and identify enrichment for textbooks. Many school districts post information about the curriculum and supplemental materials on websites for public access. [4] Teachers receive a book to give to the students for each subject and brief overviews of what they are expected to teach.[12] In general, a student learns basic arithmetic and sometimes rudimentary algebra in mathematics, English proficiency (such as basic grammar, spelling, and vocabulary), and fundamentals of other subjects. Learning standards are identified for all areas of curriculum by individual States, including those for math, social studies, science, physical development, the fine arts as well as reading. [5] While the concept of State Learning standards has been around for some time, No Child Left Behind has mandated standards exist at the State level.

Elementary School teachers are trained with emphases on human cognitive and psychological development and the principles of curriculum development and instruction earning either a Bachelors or Masters Degree in Early Childhood and Elementary Education. The teaching of social studies and science are often underdeveloped in some elementary school programs and some attribute this to the fact that elementary school teachers are trained as generalists. However, teachers attribute this to the priority placed on developing reading, writing and math proficiency in the elementary grades and the amount of time needed to do so. Reading, writing and math proficiency greatly affect performance in social studies, science and other content areas. Certification standards for teachers are determined by individual States, with individual colleges and universities determining the rigor of the college education provided for future teachers. Some states require content area tests as well as instructional skills tests to be certified as a teacher within that state.[6] Social studies may include key events, documents, understandings, and concepts in American and world history and geography and, in some programs, state or local history and geography; science varies widely. Most States have predetermined the number of minutes that will be taught within a given content area. As No Child Left Behind focuses on reading and math as primary targets for improvement, other instructional areas have received less attention. [7] There is much discussion within educational circles about the justification and impact of singularly focusing on reading and math as tested areas for improvement. [8]

Junior and senior high school

Junior high school is any school intermediate between elementary school and senior high school. It usually includes grades seven and eight, and sometimes six or nine. The term "Middle School" has supplanted "Junior High School" in the last twenty years because educators no longer wanted intermediate education to be based on a high school model, believing it to be inappropriate. In some locations, intermediate school includes grade nine only, allowing students to adjust to a high school environment. However, the goal of middle schools in recent years has been to address the unique educational and developmental needs of early adolescents, therefore middle schools have attempted to create a learning environment that is different from elementary school and different from high school. At this time, students begin to enroll in class schedules where they take classes from several teachers in a given day, unlike in elementary school where most classes are taught by the same teacher. The classes are usually a strict set of science, math, English, and social science courses, interspersed with a reading and/or technology class. Many schools now require a world language course. Every grade from kindergarten through ninth grade usually includes a mandatory physical education (P.E.) class. Student-chosen courses, known as electives, are generally limited to only one or two classes. Starting in ninth grade, grades become part of a student’s official transcript. Future employers or colleges may want to see steady improvement in grades and a good attendance record on the official transcript. Therefore, students are encouraged to take much more responsibility for their education.

Senior high school is a school attended after middle school or junior high school. High school is often used instead of senior high school and distinguished from junior high school.

Basic curricular structure

Generally, at the secondary school level, students take a broad variety of classes without special emphasis in any particular subject. Curricula vary widely in quality and rigidity; for example, some states consider 70 (on a 100-point scale) to be a passing grade, while others consider it to be as low as 60 or as high as 75.

The following are the typical minimum course sequences that one must take in order to obtain a high school diploma; they are not indicative of the necessary minimum courses or course rigor required for attending college in the United States:

- Science (usually three years minimum, including biology, chemistry, physics)

- Mathematics (usually three years minimum, including algebra, geometry, algebra II, and/or precalculus/trigonometry)

- English (four years)

- Social Science (various history, government, and economics courses, always including American history)

- Physical education (at least one year)

Many states require a "health" course in which students learn about anatomy, nutrition, first aid, sexuality, and birth control. Anti-drug use programs are also usually part of health courses. Foreign language and some form of art education are also a mandatory part of the curriculum in some schools.

Electives

Many secondary schools offer a wide variety of elective courses, although the availability of such courses depends upon each particular school's financial resources and desired curriculum emphases.

Common types of electives include:

- Visual arts (drawing, sculpture, painting, photography, film)

- Performing Arts (drama, band, chorus, orchestra, dance)

- Technology education ("Shop"; woodworking, metalworking, automobile repair, robotics)

- Computers (word processing, programming, graphic design)

- Athletics (cross country, football, baseball, basketball, track and field, swimming, gymnastics, water polo, soccer)

- Publishing (journalism/student newspaper, yearbook, literary magazine)

- Foreign languages (French, German, and Spanish are common; Chinese, Latin, Greek and Japanese are less common)[13]

Additional options for gifted students

Not all schools require the same rigor of course work. Students perform to their highest possible potential when they are given less free time, such as free periods and open classes. This causes for a break in the mental process and puts the students at a disadvantage when it comes to test taking. (Dr. Harvey 2002). Most senior high, junior high, and elementary schools offer "honors" or "gifted" classes for motivated and gifted students, where the quality of education is usually higher and more demanding. There are also magnet schools that may have competitive entrance requirements.[14]

If funds are available, a high school may provide Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate courses, which are special forms of honors classes. AP or IB courses are usually taken during the 11th or 12th grade of high school, either as a replacement for a typical required course (e.g., taking AP U.S. History as a replacement for standard U.S. History), a continuation of a subject (e.g., taking AP Biology in the 12th grade even though one already took Biology in the 9th grade), or a completely new field of study (e.g., AP Economics or AP Computer Science).

Most post-secondary institutions take AP or IB exam results into consideration in the admissions process. Because AP and IB courses are intended to be the equivalent of the first year of college courses, post-secondary institutions may grant unit credit which enables students to graduate early. Other institutions use examinations for placement purposes only: students are exempted from introductory course work but may not receive credit towards a concentration, degree, or core requirement. Institutions vary in the selection of examinations they accept and the scores they require to grant credit or placement, with more elite institutions tending to accept fewer examinations and requiring higher scoring. The lack of AP, IB, and other advanced courses in impoverished inner-city high schools is often seen as a major cause of the greatly differing levels of post-secondary education these graduates go on to receive, compared with both public and private schools in wealthier neighborhoods.

Also, in states with well-developed community college systems, there are often mechanisms by which gifted students may seek permission from their school district to attend community college courses full time during the summer, and during weekends and evenings during the school year. The units earned this way can often be transferred to one's university, and can facilitate early graduation. Early college entrance programs are a step further, with students enrolling as freshmen at a younger-than-traditional age.

Extracurricular activities

A major characteristic of American schools is the high priority given to sports, clubs and activities by the community, the parents, the schools and the students themselves. Many elementary, junior high, and senior high students participate in extracurricular activity. Extracurricular activity is educational activities not falling within the scope of the regular curriculum but under the supervision of the school. These activities can extend to large amounts of time outside the normal school day; home-schooled students, however, are not normally allowed to participate. Student participation in sports programs, drill teams, bands, and spirit groups can amount to hours of practices and performances. Most states have organizations which develop rules for competition between groups. These organizations are usually forced to implement time limits on hours practiced as a prerequisite for participation. Many schools also have non-varsity sports teams, however these are usually afforded less resources and attention. The idea of having sports teams associated with high schools is relatively unique to the United States in comparison with other countries.

Sports programs and their related games, especially football and/or basketball, are major events for American students and for larger schools can be a major source of funds for school districts. Schools may sell "spirit" shirts to wear to games; school stadiums and gymnasiums are often filled to capacity, even for non-sporting competitions.

High school athletic competitions often generate intense interest in the community. Inner city schools serving poor students are heavily scouted by college and even professional coaches, with national attention given to which colleges outstanding high school students choose to attend. State high school championship tournaments football and basketball attract high levels of public interest.

In addition to sports, numerous non-athletic extracurricular activities are available in American schools, both public and private. Activities include musical groups, marching bands, student government, school newspapers, science fairs, debate teams, and clubs focused on an academic area, such as the Spanish Club.

Standardized testing

Under the No Child Left Behind Act, all American states must test students in public schools statewide to ensure that they are achieving the desired level of minimum education,[15] such as on the Regents Examinations in New York or the Pennsylvania System of School Assessment (PSSA); students being educated at home or in private schools are not included. The Act also requires that students and schools show "adequate yearly progress." This means they must show some improvement each year.

Although these tests may have revealed the results of student learning, they may have little value to help strengthen the students' academic weakness. For example, in most states, the results of the testing would not be known until six months later. At that time, the students have been promoted to the next grade or entering a new school. The students are not given a chance to review the questions and their own answers but their percentile of the test results are compared with their own peers. To address this situation many school districts have implemented MAP. Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) tests are state-aligned computerized adaptive assessments that measure the instructional level of each student's growth over time.[9]

This research based testing allows elementary school teachers to have on going access to student progress. Teachers using this system can identify strengths and weaknessess of individual students and remediate where necessary. When a student fails to make adequate yearly progress, No Child Left Behind mandates remediation through summer school and/or tutoring be made available to a given student.

During high school, students (usually in 11th grade) may take one or more standardized tests depending on their postsecondary education preferences and their local graduation requirements. In theory, these tests evaluate the overall level of knowledge and learning aptitude of the students. The SAT and ACT are the most common standardized tests that students take when applying to college. A student may take the SAT, ACT, or both depending upon the college the student plans to apply to for admission. Most competitive schools also require two or three SAT Subject Tests, (formerly known as SAT IIs), which are shorter exams that focus strictly on a particular subject matter. However, all these tests serve little to no purpose for students who do not move on to postsecondary education, so they can usually be skipped without affecting one's ability to graduate.

Education of students with special needs

In the United States, education for children identified with disabilities is structured to adhere as closely as possible to the same experience received by their typically developing peers. This is perhaps one one of the more unique concepts of education within the United States of America. Within the Federal law, all children are entitled to a free and appropriate public education, FAPE, as mandated in the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 IDEA. Blind and deaf students usually have separate classes in which they spend most of their day, but may sit in on normal classes with guides or interpreters.

People identified with special needs such as borderline mental retardation are required to attend the same amount of time as other students. Federal law requires that states ensure that all school districts provide services to meet the individual needs of students with disabilities IDEA. Students must be placed in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE). This means that school districts must meet with the parents to develop an Individualized Educational Plan that determines best placement for their child. School districts that fail to provide an appropriate placement for children identified with special needs can be taken to due process wherein parents may legally and formally submit their grievances and demand appropriate services for their child.

Some children with developmental delays and other disabilities are placed in self contained classrooms. These special education classrooms are provided for children who do not benefit educationally, socially or emotionally from a standard classroom placement. These classes, commonly known as special education or special ed, are taught by teachers with training in adapting curriculum to meet the needs of children identified with special needs. Depending on the degree and severity of mental impairment, social/emotional or physical disabilities, students with special needs may participate in regular education classes with typically developing peers classes as much as the child might benefit from such a placement. When a child with special needs is placed in a regular classroom for all or part of his educational experience, Special Education Teachers are responsible for providing adaptive supports and modifications to allow for the child to learn within that environment. This educational setting is known as inclusion. All adaptations and modifications should be relevant to the child's disability and appropriate to the identified disability. The level of inclusion that is provided varies greatly within different school districts. Children receiving Special Education services are entitled by law to an annual review of yearly progress as well as an evaluation every three years to determine the needs for continued services. Parents who have specific desires for their child's education must act as advocates to assure their child's best interests are being met.

In order to more clearly determine students as disabled, the federal government defined thirteen categories of disabilities. These included autism, deaf-blindness, deafness, hearing impairment, mental retardation, multiple disabilities, orthopedic impairment, other health impairment, serious emotional disturbance, specific learning disability, speech or language impairment, traumatic brain injury, and visual impairment. Sometimes these students are able to attend special sessions during the day to supplement regular class time; here they often receive extra instruction or perform easier work. The goal of these programs, however, is to try to bring everyone up to the same standard and provide equal opportunity to those students who are challenged. The federal government supports the standards developed in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004.[16] The law mandates that schools must accommodate students with disabilities as defined by the act, and specifies methods for funding the sometimes large costs of providing them with the necessary facilities. Larger districts are often able to provide more adequate and quality care for those with special needs.

Public and Private schools

Unlike most other industrialized countries, the United States does not have a centralized educational system on the national scale.[17] Thus, K-12 students in most areas have a choice between free tax-funded public schools, or (usually) privately-funded, private schools.

Public school systems are supported by a combination of local, state, and federal government funding. Because a large portion of school revenues come from local property taxes, public schools vary widely in the resources they have available per student. Class size also varies significantly from one district to another. Generally, schools in more affluent areas are more highly regarded; it is this fact that is often blamed for what some perceive as lack of social mobility in America. Curriculum decisions in public schools are made largely at the local and state levels; the federal government has limited influence. In most districts a locally elected school board runs schools. The school board appoints an official called the superintendent of schools to manage the schools in the district. The largest public school system in the United States is in New York City, where more than one million students are taught in 1,200 separate public schools. Because of its immense size - there are more students in the system than residents in eight US states - the New York City public school system is nationally influential in determining standards and materials like text books.

All public school systems are required to provide an education free of charge to everyone of school age in their districts. Admission to individual public schools is usually based on residency. To compensate for differences in school quality based on geography, large cities often have "magnet schools" that provide enrollment to a specified number of non-resident students in addition to serving all resident students. This special enrollment is usually decided by lottery with equal numbers of boys and girls chosen. Some magnet schools cater to gifted students or to students with special interests, such as the sciences or performing arts.[14] Admission to some of these schools is highly competitive and based on an application process.

Private schools in the United States include parochial schools (affiliated with religious denominations), non-profit independent schools, and for-profit private schools. Private schools charge varying rates depending on geographic location, the school's expenses, and the availability of funding from sources, other than tuition. For example, some churches partially subsidize private schools for their members. Some people have argued that when their child attends a private school, they should be able to take the funds that the public school no longer needs and apply that money towards private school tuition in the form of vouchers; this is the basis of the school choice movement.

Private schools have various missions: Some cater to college-bound students seeking a competitive edge in the college admissions process; others are for gifted students, students with learning disabilities or other special needs, or students with specific religious affiliations. Some cater to families seeking a small school, with a nurturing, supportive environment. Unlike public school systems, private schools have no legal obligation to accept any interested student. Admission to some private schools is highly selective. Private schools also have the ability to permanently expel persistently unruly students, a disciplinary option not always legally available to public school systems. Private schools offer the advantages of smaller classes, under twenty students in a typical elementary classroom, for example; a higher teacher/student ratio across the school day, greater individualized attention and in the more competitive schools, expert college placement services. Unless specifically designed to do so, private schools usually cannot offer the services required by students with serious or multiple learning, emotional, or behavioral issues. Although reputed to pay lower salaries than public school systems, private schools often attract teachers by offering high-quality professional development opportunities, including tuition grants for advanced degrees. This investment in faculty development helps maintain the high quality program that elite private schools claim to offer.

The United States Department of Education released a statement recently detailing the average cost per pupil in public and private schools, and found that the average public school cost was approximately USD$7,200 per student while the average private school cost per pupil was just USD$3,500. The Department of Education also stated that less than 25% of private schools are considered "elite," costing more than $10,000 a year. In contrast, private schools in East Asia average around USD$1,400 per year.[citation needed]

College and University

Post-secondary education in the United States is known as college or university and commonly consists of four years of study at an institution of higher learning. Like high school, the four undergraduate grades are commonly called freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior years (alternately called first year, second year, etc.). Students traditionally apply to receive admission into college, with varying difficulties of entrance. Schools differ in their competitiveness and reputation; generally, the most prestigious schools are private, rather than public. Admissions criteria involve the rigor and grades earned in high school courses taken, the students GPA, class ranking, and standardized test scores (Such as the SAT or the ACT tests). Most colleges also consider more subjective factors such as a commitment to extracurricular activities, a personal essay, and an interview. While numerical factors rarely ever are absolute required values, each college usually has a rough threshold below which admission is unlikely.

Once admitted, students engage in undergraduate study, which consists of satisfying university and class requirements to achieve a bachelor's degree in a field of concentration known as a major. (Some students enroll in double majors or "minor" in another field of study.) The most common method consists of four years of study leading to a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.), a Bachelor of Science (B.S.), or sometimes (but rarely) another bachelor's degree such as Bachelor of Fine Arts (B.F.A.), Bachelor of Social Work (B.S.W.), Bachelor of Engineering (B.Eng.,) or Bachelor of Philosophy (B.Phil.) Five-Year Professional Architecture programs offer the Bachelor of Architecture Degree (B.Arch.)

Unlike in the British model, degrees in law and medicine are not offered at the undergraduate level and are completed as graduate study after earning a bachelor's degree. Neither field specifies or prefers any undergraduate major, though medicine has set prerequisite courses that must be taken before enrollment.

Some students choose to attend a community college for two years prior to further study at another college or university. In most states, community colleges are operated either by a division of the state university or by local special districts subject to guidance from a state agency. Community colleges may award Associate of Arts (AA) or Associate of Science (AS) degree after two years. Those seeking to continue their education may transfer to a four-year college or university (after applying through a similar admissions process as those applying directly to the four-year institution, see articulation). Some community colleges have automatic enrollment agreements with a local four-year college, where the community college provides the first two years of study and the university provides the remaining years of study, sometimes all on one campus. The community college awards the associate's degree, and the university awards the bachelor's and master's degrees.

Graduate study, conducted after obtaining an initial degree and sometimes after several years of professional work, leads to a more advanced degree such as a master's degree, which could be a Master of Arts (MA), Master of Science (MS), Master of Business Administration (MBA), or other less common master's degrees such as Master of Education (MEd), and Master of Fine Arts (MFA). After additional years of study and sometimes in conjunction with the completion of a master's degree, students may earn a Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) or other doctoral degree, such as Doctor of Arts, Doctor of Education, Doctor of Theology, Doctor of Medicine, Doctor of Pharmacy, Doctor of Physical Therapy, or Doctor of Jurisprudence. Some programs, such as medicine, have formal apprenticeship procedures post-graduation like residency and internship which must be completed after graduation and before one is considered to be fully trained. Other professional programs like law and business have no formal apprenticeship requirements after graduation (although law school graduates must take the bar exam in order to legally practice law in nearly all states).

Entrance into graduate programs usually depends upon a student's undergraduate academic performance or professional experience as well as their score on a standardized entrance exam like the Graduate Record Examination (GRE-graduate schools in general), the Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT), or the Law School Admissions Test (LSAT). Many graduate and law schools do not require experience after earning a bachelor's degree to enter their programs; however, business school candidates are usually required to gain a few years of professional work experience before applying. Only 8.9 percent of students ever receive postgraduate degrees, and most, after obtaining their bachelor's degree, proceed directly into the workforce.[18]

Cost

The vast majority of students (up to 70 percent) lack the financial resources to pay tuition up front and must rely on student loans and scholarships from their university, the federal government, or a private lender. All but a few charity institutions charge all students tuition, although scholarships (both merit-based and need-based) are widely available. Generally, private universities charge much higher tuition than their public counterparts, which rely on state funds to make up the difference. Because each state supports its own university system with state taxes, most public universities charge much higher rates for out-of-state students. Private universities are generally considered to be of higher quality than public universities, although there are many exceptions.

Annual undergraduate tuition varies widely from state to state, and many additional fees apply. A typical year's tuition at a public university (for residents of the state) is about $5,000. Tuition for public school students from outside the state is generally comparable to private school prices, although students can generally get state residency after their first year. Private schools are typically much higher, although prices vary widely from "no-frills" private schools to highly specialized technical institutes. Depending upon the type of school and program, annual graduate program tuition can vary from $15,000 to as high as $40,000. Note that these prices do not include living expenses (rent, room/board, etc.) or additional fees that schools add on such as "activities fees" or health insurance. These fees, especially room and board, can range from $6,000 to $12,000 per academic year (assuming a single student without children).[19]

College costs are rising at the same time that state appropriations for aid are shrinking. This has led to debate over funding at both the state and local levels. From 2002 to 2004 alone, tuition rates at public schools increased by just over 14 percent, largely due to dwindling state funding. A more moderate increase of 6 percent occurred over the same period for private schools.[19]

Private colleges and universities have also sought out different measures to help students and parents combat the rising costs of a college education. Many schools participate in college savings plans. In one case, private colleges and universities from across the country joined together to form Tuition Plan Consortium, the not-for-profit organization that sponsors Independent 529 Plan. The first private college-sponsored 529 plan, Independent 529 Plan allows families to buy tuition before their children are enrolled in college and avoid years of tuition inflation. In addition, each participating school offers a “discount,” so tuition is pre-paid at less than the current price.

The status ladder

American college and university faculty, staff, alumni, students, and applicants monitor rankings produced by magazines such as U.S. News and World Report, Academic Ranking of World Universities, test preparation services such as The Princeton Review or another university itself such as the Top American Research Universities by the University of Florida's TheCenter.[20] These rankings are based on factors like brand recognition, selectivity in admissions, generosity of alumni donors, and volume of faculty research.

In terms of brand recognition, the United States' best known university is Harvard. Seemingly, Harvard alumni often gain prominence in American business, education, and society; for this reason, it has become entrenched in popular mind as America's 'top' school. Various Hollywood movies depict Harvard as the ultimate example of the academic "ivory tower," (e.g., Legally Blonde, Soul Man, The Paper Chase, etc).

In the popular mind, approximately twenty-five institutions compose the "top tier" of American higher learning. However, this "ladder" is not absolute. Most would cite the eight universities that compose the Ivy League and a small number of elite, private research universities (e.g. (alphabetical order), Caltech, Duke, Johns Hopkins, MIT, Northwestern, Stanford, University of Chicago, Washington University in St. Louis, etc.)[21][22]

A small percentage of students who apply to these Ivy League schools gain admission.[23] Many Americans would also cite the "Little Ivies," a handful of elite liberal arts college known for their high-quality instruction. These include (alphabetical order) Amherst, Swarthmore, Williams, Wesleyan, etc. Others would cite all-female institutions such as Smithand Wellesley, former members of the "Seven Sisters."

This ladder also includes top public universities (sometimes referred to as "Public Ivies"), such as (alphabetical order) University of California, Berkeley, University of Michigan, University of Virginia and University of Washington. These universities actually perform better than various private universities in many measurements of graduate education and research quality.[24] Among engineering and medical schools, Ivy League universities are outranked by multiple public and other private universities.[25]

Each state in the United States maintains its own public university system, which is always non-profit. The State University of New York and the California State University are the largest public higher education systems in the United States; SUNY is the largest system that includes community colleges, while CSU is the largest without. Most areas also have private institutions which may be for-profit or non-profit. Unlike many other nations, there are no public universities at the national level outside of the military service academies. Many states have two separate state university systems. The faculty of the more prestigious system are expected to conduct advanced cutting-edge research in addition to teaching (the naming convention usually runs "University of ___" for the upper tier, e.g. the University of California), while the less prestigious is focused on quality of teaching and producing the next generation of teachers (usually named "___ State University," e.g., California State University). The second-tier university systems are often the descendants of 19th-century normal schools. Note that Texas has six (6) separate state university systems: the University of Texas System, the Texas Tech University System, the Texas A&M University System, the University of Houston System, the University of North Texas System, and the Texas State University System.

Prospective students applying to attend one of the five military academies require, with limited exceptions, nomination by a member of Congress. Like acceptance to "top tier" universities, competition for these limited nominations is intense and must be accompanied by superior scholastic achievement and evidence of "leadership potential."

Aside from these aforementioned schools, academic reputations vary widely among the 'middle-tier' of American schools, (and even among academic departments within each of these schools.) Most public and private institutions fall into this 'middle' range. Some institutions feature honors colleges or other rigorous programs that challenge academically exceptional students, who might otherwise attend a 'top-tier' college.[26][27][28][29] Aware of the status attached to the perception of the college that they attend, students often apply to a range of schools. Some apply to a relatively prestigious school with a low acceptance rate, gambling on the chance of acceptance, and also apply to a "safety school,"[30] to which they will certainly gain admission.

Low status institutions include community colleges. These are primarily two-year public institutions, which individual states usually require to accept all local residents who seek admission, and offer associate's degrees or vocational certificate programs. Many community colleges have relationships with four-year state universities and colleges or even private universities which enable their students to transfer relatively smoothly to these universities for a four-year degree after completing a two-year program at the community college.

Regardless of perceived prestige, many institutions feature (at least one) distinguished academic department, and most Americans attend one of the 2,400 four-year colleges and universities or 1,700 two-year colleges not included among the twenty-five or so 'top-tier' institutions.[31] For this reason (among others,) America's higher education status ladder remains highly controversial, and certainly not beyond reproach. For example, prestigious Reed College famously refuses to participate in institutional rankings, insisting that one cannot quantify the qualitative. Similarly, Bard College president Leon Botstein said of U.S. News' annual rankings; "it is the most successful journalistic scam I have seen in my entire adult lifetime -- corrupt, intellectually bankrupt and revolting."

Contemporary education issues

Major educational issues in the United States center on curriculum, funding, and control. Of critical importance, because of its enormous implications on education and funding, is the No Child Left Behind Act.[15]

Curriculum issues

Curriculum in the United States varies widely from district to district. Not only do schools offer an incredible range of topics and quality, but private schools may include religious classes as mandatory for attendance (this also begets the problem of government funding vouchers; see below). This has produced camps of argument over the standardization of curriculum and to what degree. Some feel that schools should be nationalized and the curriculum changed to a national standard.[citation needed] These same groups often are advocates of standardized testing, which is mandated by the No Child Left Behind Act. Aside from who controls the curriculum, groups argue over the teaching of the English language, evolution, and sex education.[citation needed]

A large issue facing the curriculum today is the use of the English language in teaching. English is spoken by over 95% of the nation, and there is a strong national tradition of upholding English as the de facto official language. Some 9.7 million children aged 5 to 17 primarily speak a language other than English at home. Of those, about 1.3 million children speak English "not well" or "not at all."[32] While a few, mostly Hispanic, groups want bilingual education, the majority of school districts are attempting to use English as a Second Language (ESL) course to teach Spanish-speaking students English. In addition, many feel there are threats to the "integrity" of the language itself. For example, there has been discussion about whether to classify as a "second language" the dialect called African American Vernacular English (known colloquially as Ebonics, a portmanteau of "ebony" and "phonics"). While it is not taught in any American schools, debate continues over its place in education.

In 1999 the School Board of the state of Kansas caused controversy when it decided to eliminate testing of evolution in its state assessment tests.[33] This caused outrage among scientists and average citizens alike, but was widely supported in Kansas.[citation needed] However, intense media coverage and the national spotlight persuaded the board to eventually overturn the decision. As of 2005, such controversies have not abated. Not surprisingly, scientific observers stress the importance of evolution in the curriculum and some dislike the idea of intelligent design or creationist ideas being taught since it brings religions, like Islam and Christianity, into disscussion. Some fundamentalist religious and "family values" groups, on the other hand, stress the need to teach creationism in the public schools. While a majority of United States citizens approve of teaching evolution, many also also support teaching intelligent design and/or creationism in public schools. Support for evolution was also found to be greater among the more educated.[34]

Today, sex education ("sex ed") in the United States is highly controversial. Many schools attempt to avoid the study as much as possible, confining it to a unit in health classes. There are few specifically sex education classes in existence. Also, because President Bush has called for abstinence-only sex education and has the power to withhold funding,[35] many schools are backing away from instructing students in the use of birth control or contraceptives.

However, according to a 2004 survey, a majority of the 1001 parent groups polled wants complete sex education in the schools. The American people are heavily divided over the issue. Many agreed with the statement "Sex education in school makes it easier for me to talk to my child about sexual issues," while a proportion disagreed with the statement that their children were being exposed to "subjects I don't think my child should be discussing." Also, only 10 percent believed that their children's sexual education class forced them to discuss sexual issues "too early." On the other hand, 49 percent of the respondents (the largest group) were only "somewhat confident" that the values taught in their children's sex ed classes were similar to those taught at home, and 23 percent were less confident still. (The margin of error was plus or minus 4.7 percent.)[36]

There is constant debate over which subjects should receive the most focus, with astronomy and geography among those cited as not being taught enough in schools.[37][38][39][40]

Funding

Funding for schools in the United States is complex. One current controversy stems much from the No Child Left Behind Act. The Act gives the Department of Education the right to withhold funding if it believes a school, district, or even a state is not complying and is making no effort to comply. However, federal funding accounts for little of the overall funding schools receive. The vast majority comes from the state government and from local property taxes. Various groups, many of whom are teachers, constantly push for more funding. They point to many different situations, such as the fact that in many schools, teachers, especially those at the elementary level, must supplement their supplies with purchases of their own.[41]

Property taxes as a primary source of funding for public education have become highly controversial, for a number of reasons. First, if a state's population and land values escalating rapidly, many longtime residents may find themselves paying property taxes much higher than anticipated. In response to this phenomenon, California's citizens passed Proposition 13 in 1978, which severely restricted the ability of the Legislature to expand the state's educational system to keep up with growth.

Another issue is that many parents of private school and homeschooled children have taken issue with the idea of paying for an education their children are not receiving. However, tax proponents point out that every person pays property taxes for public education, not just parents of school-age children. Indeed, without it schools would not have enough money to remain open. Still, parents of students who go to private schools want to use this money instead to fund their children's private education. This is the foundation of the school voucher movement. School voucher programs were proposed by free-market advocates seeking competition in education, led by economist Milton Friedman. Herbst (2005) describes the evolution of voucher programs.

One of the biggest debates in funding public schools is funding by local taxes or state taxes. The federal government supplies around 8.5% of the public school system funds, according to a 2005 report by the National Center for Education Statistics. The remaining split between state and local governments averages 48.7 percent from states and 42.8 percent from local sources. However, the division varies widely. In Hawaii local funds make up only 1.7 percent, while state sources account for nearly 90.1 percent.[42]

At the college and university level, funding becomes an issue due to the sheer complexity of gaining it. Some of the reason for the confusion at the college/university level in the United States is that student loan funding is split in half; half is managed by the Department of Education directly, called the Federal Direct Student Loan Program (FDSLP). The other half is managed by commercial entities such as banks, credit unions, and financial services firms such as Sallie Mae, under the Federal Family Education Loan Program (FFELP). Some schools accept only FFELP loans; others accept only FDSLP. Still others accept both, and a few schools will not accept either, in which case students must seek out private alternatives for student loans.

Charter Schools

Herbst (2006) explains the charter-school movement was born in 1990. Charter schools have spread rapidly in the United States, based on the promise to create less bureaucratic schools that vest "management authority in a group of community members, parents, teachers, and students" to allow for the "expression of diverse teaching philosophies and cultural and social life styles" (Herbst p. 107). Herbst ultimately maintains that charter schools have produced mixed results. Recent studies confirm that charter-school students do not out-perform their public-school counterparts. Herbst concludes that federal intervention in public and private education has only increased since the 1990s. The federal government's involvement culminated in the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, which extends federal oversight of state schools and grants parents the choice of removing their children from persistently failing schools.

Control

There is some debate about where control for education actually lies. Education is not mentioned in the constitution of the United States. In the current situation, the state and national governments have a power-sharing arrangement, with the states exercising most of the control. Like other arrangements between the two, the federal government uses the threat of decreased funding to enforce laws pertaining to education.[17] Furthermore, within each state there are different types of control. Some states have a statewide school system, while others delegate power to county, city or township-level school boards. However, under the Bush administration, initiatives such as the No Child Left Behind Act have attempted to assert more central control in a heavily decentralized system.

The U.S. federal government exercises its control through the U.S. Department of Education. School accreditation decisions are made by voluntary regional associations. Schools in the 50 states and the District of Columbia teach in English, while schools in the territory of Puerto Rico teach in Spanish. Nonprofit private schools are widespread, are largely independent of the government, and include secular as well as parochial schools.

Competitiveness

The national results in international comparisons have often been below the average of developed countries. In OECD's Programme for International Student Assessment 2003, 15 year olds ranked 24th of 38 in mathematics, 19th of 38 in science, 12th of 38 in reading, and 26th of 38 in problem solving.[43] In addition, many business leaders have expressed concerns that the quality of education given in the US system is generally below acceptable standards, and should be adapted in order to conform to the needs of an evolving world. Bill Gates has famously stated that the American high school is "obsolete".[44]

History

In the subject of teaching in the United States, many other countries criticize the fact that American students learn very little about the world outside America. This has long been the subject of a section on Australian ABC comedy The Chasers War on Everything called "Firth in the U.S.A". Charles Firth attempted to pass off well-known historical world landmarks as Australian, such as the Leaning Tower of Pisa and Mount Rushmore. All those interviewed believed him.

See also

- Educational attainment in the United States

- Education in Colonial America

- Public education

- Outcome-based education

- Universities in the United States

- Lists of school districts in the United States

- Lists of high schools in the United States

- Category:Lists of schools

- Scouting in the United States

- College Board examinations

- ACT examination

- Kingswood Regional High School

Bibliography

- John E. Chubb and Terry M. Moe. Politics, Markets and America's Schools (1990)

- Kosar, Kevin R. Failing Grades: The Federal Politics of Education Standards. Rienner, 2005. 259 pp.

- E. Wayne Ross et al eds. Defending Public Schools. (Praeger, 2004), 4 vol: Volume: 1: Education Under the Security State (2004) online version; Volume: 2: Teaching for a Democratic Society (2004) online version; Volume: 3: Curriculum Continuity and Change in the 21st Century (2004) online version; Volume: 4: The Nature and Limits of Standards-Based Reform and Assessment (2004) online version

- Tyack, David. Seeking Common Ground: Public Schools in a Diverse Society. Harvard U. Pr., 2003. 237 pp.

History

for more detailed bibliography see History of Education in the United States: Bibliography

- James D. Anderson, The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935 (University of North Carolina Press, 1988).

- Axtell, J. The school upon a hill: Education and society in colonial New England. Yale University Press. (1974).

- Maurice R. Berube; American School Reform: Progressive, Equity, and Excellence Movements, 1883-1993. 1994. online version

- Brint, S., & Karabel, J. The Diverted Dream: Community colleges and the promise of educational opportunity in America, 1900–1985. Oxford University Press. (1989).

- Button, H. Warren and Provenzo, Eugene F., Jr. History of Education and Culture in America. Prentice-Hall, 1983. 379 pp.

- Cremin, Lawrence A. The transformation of the school: Progressivism in American education, 1876–1957. (1961).

- Cremin, Lawrence A. American Education: The Colonial Experience, 1607–1783. (1970); American Education: The National Experience, 1783–1876. (1980); American Education: The Metropolitan Experience, 1876-1980 (1990); standard 3 vol detailed scholarly history

- Curti, M. E. The social ideas of American educators, with new chapter on the last twenty-five years. (1959).

- Dorn, Sherman. Creating the Dropout: An Institutional and Social History of School Failure. Praeger, 1996. 167 pp.

- Herbst, Juergen. The once and future school: Three hundred and fifty years of American secondary education. (1996).

- Herbst, Juergen. School Choice and School Governance: A Historical Study of the United States and Germany 2006. ISBN 1-4039-7302-4.

- Krug, Edward A. The shaping of the American high school, 1880–1920. (1964); The American high school, 1920–1940. (1972). standard 2 vol scholarly history

- Lucas, C. J. American higher education: A history. (1994).

pp.; reprinted essays from History of Education Quarterly

- Parkerson, Donald H. and Parkerson, Jo Ann. Transitions in American Education: A Social History of Teaching. Routledge, 2001. 242 pp.

- Parkerson, Donald H. and Parkerson, Jo Ann. The Emergence of the Common School in the U.S. Countryside. Edwin Mellen, 1998. 192 pp.

- Peterson, Paul E. The politics of school reform, 1870–1940. (1985).

- Ravitch, Diane. Left Back: A Century of Failed School Reforms. Simon & Schuster, 2000. 555 pp.

- John L. Rury; Education and Social Change: Themes in the History of American Schooling.'; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 2002. online version

- Sanders, James W The education of an urban minority: Catholics in Chicago, 1833–1965. (1977).

- Solomon, Barbara M. In the company of educated women: A history of women and higher education in America. (1985).

- Theobald, Paul. Call School: Rural Education in the Midwest to 1918. Southern Illinois U. Pr., 1995. 246 pp.

- David B. Tyack. The One Best System: A History of American Urban Education (1974),

- Tyack, David and Cuban, Larry. Tinkering toward Utopia: A Century of Public School Reform. Harvard U. Pr., 1995. 184 pp.

- Tyack, David B., & Hansot, E. Managers of virtue: Public school leadership in America, 1820–1980. (1982).

- Veysey Lawrence R. The emergence of the American university. (1965).

- ^ "Human development indicators" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Reports. Retrieved 2006-11-07.

- ^ a b c Education. United States Census (2000). URL accessed on June 17, 2005.

- ^ A First Look at the Literacy of America’s Adults in the 21st Century, U.S. Department of Education, 2003. Accessed May 13, 2006. 2% of the population do not have minimal literacy and 14% have Below Basic prose literacy.

- ^ Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), OECD, reading literacy, science literacy and mathematics literacy all rank near the bottom of OECD-countries.

- ^ Education at Glance 2005 by OECD: Current tertiary graduation rates.

- ^ Education at Glance 2005 by OECD: Participation in continuing education and training

- ^ Structure of U.S. Education. U.S. Network for Education Information: U.S. Department of Education. URL accessed on February 19, 2005.

- ^ Educational Consultants. About.com (2005). URL accessed on August 12, 2005.

- ^ State Compulsory School Attendance Laws. Information Please Almanac. URL accessed on July 3, 2005.

- ^ Aronold, Dave. Home Schools Run By Well-Meaning Amateurs. National Education Association. URL accessed on February 19, 2005.

- ^ Home School Legal Defense Association. URL accessed February 13, 2007.

- ^ Fast Facts. National Center for Education Statistics. URL accessed on July 3, 2005.

- ^ Enrollment in foreign language courses. National Center for Education Statistics. URL accessed on January 16, 2006.

- ^ a b Klauke, Amy. Magnet schools. ERIC Clearinghouse on Educational Management. URL accessed on February 21, 2005. Cite error: The named reference "eric" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Executive Summary of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. U.S. Department of Education. URL accessed on February 16, 2006.

- ^ IDEA 2004 Resources. U.S. Department of Education. URL accessed on February 16, 2006.

- ^ a b Federal Role in Education. United States Department of Education. URL accessed on February 16, 2006. Cite error: The named reference "doe2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Educational attainment of persons 18 years old and over. National Center for Education Statistics. URL accessed on January 6, 2005.

- ^ a b Tuition Levels Rise but Many Students Pay Significantly Less than Published Rates. The College Board (2003). URL accessed on June 20, 2005.

- ^ "The Top American Research Universities" (HTML). The Center (University of Florida). Retrieved 2006-11-07.

- ^ "Who Needs Harvard?" (HTML). The Atlantic Online. Retrieved 2006-11-07.

- ^ "What's the Value of an Ivy Degree?" (HTML). The Dartmouth Review. Retrieved 2006-11-07.

- ^ Ivy League College Admissions Facts and Statistics. Admissions Consultants. URL accessed on February 18, 2005.

- ^ the Top American Research Universities by University of Florida TheCenter

- ^ http://www.usnews.com/usnews/edu/grad/rankings/eng/brief/engrank_brief.php

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CUNY_Honors_College#The_Honors_College

- ^ Schreyer Honors College

- ^ http://www.valpo.edu/christc/

- ^ http://www.baylor.edu/honors_college/splash.php

- ^ More than a 'safety school'. The Daily Targum. URL accessed on February 16, 2005.

- ^ http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0908742.html

- ^ Summary Tables on Language Use and English Ability: 2000. United States Census (2000). URL accessed on February 6, 2006.

- ^ Kansas school board's evolution ruling angers science community. CNN.com (1999). URL accessed on August 12, 2005.

- ^ Poll: Creationism Trumps Evolution. CBS News Polls (2004). URL accessed on June 20, 2005.

- ^ Abstinence Only Sex Education Program in Schools. About.com. URL accessed on February 15, 2006.

- ^ Sex Education in America - General Public/Parents Survey. NPR/Kaiser/Harvard survey (2004). URL accessed on June 17, 2005.

- ^ "http://www.astrosociety.org/education/resources/useduc03.html".

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); External link in|title= - ^ "http://genip.tamu.edu/".

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); External link in|title= - ^ "Geography Education in the United States".

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); External link in|title= - ^ "http://geography.about.com/library/misc/bldeblij1.htm".

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); External link in|title= - ^ Teachers Dig Deeper to Fill Gap in Supplies. New York Times article (2002). URL accessed on June 26, 2005.

- ^ Revenues and Expenditures for Public Elementary and Secondary Education, Table 1. National Center for Education Statistics. URL accessed on February 15, 2006.

- ^ International Outcomes of Learning in Mathematics Literacy and Problem Solving. National Center for Education Statistics. URL accessed February 18, 2005.

- ^ Gates Foundation Puts $2.3B Into Education. ABC News Online (2005). URL accessed on June 26, 2005.

External links

- U.S. Department of Education

- National Center for Education Statistics

- All About US Admissions

- National Assessment of Educational Progress

- Public education in the United States

- Social Studies issues in school textbook

- Syllabus and bibliography on history of American Education, by Carl Kaestle (2005)

- High Schools Directory

- The Heartland Institutes' School Reform Issue Suite

- Independent 529 Plan