History of Indiana: Difference between revisions

→Early development: convert to short ref |

cleaning up refs |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

===Founding=== |

===Founding=== |

||

In February 1815, the [[United States House of Representatives]] began debate on granting Indiana Territory statehood. In early 1816, the Territory approved a [[census]] and Pennington was named to be the [[enumerator|census enumerator]]. The population of the territory was found to be 63,897,<ref>Haymond, p. 181</ref> above the limit required for statehood that was stated in the Northwest Ordinance. On [[May 13]], [[1816]], the Enabling Act was passed and the state was granted permission to form a government subject to the approval of [[United States Congress|Congress]].<ref>Funk, p. 42</ref> A constitutional convention met in 1816 in [[Corydon, Indiana|Corydon]]. The [[Constitution of Indiana|state's first constitution]] was drawn up on June 10, and elections were held in August to fill the offices of the new state government. In November of that year the constitution was approved by Congress and the territorial government was dissolved, ending the existence of the Indiana Territory and replacing it with the State of Indiana.<ref>Funk, p. 35</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.centerforhistory.org/indiana_history_main3.html|publisher=Indiana Center For History|title=''Indiana History Chapter three''|accessdate=2008-05-17}}</ref> |

In February 1815, the [[United States House of Representatives]] began debate on granting Indiana Territory statehood. In early 1816, the Territory approved a [[census]] and Pennington was named to be the [[enumerator|census enumerator]]. The population of the territory was found to be 63,897,<ref>Haymond, p. 181</ref> above the limit required for statehood that was stated in the Northwest Ordinance. On [[May 13]], [[1816]], the Enabling Act was passed and the state was granted permission to form a government subject to the approval of [[United States Congress|Congress]].<ref>Funk, p. 42</ref> A constitutional convention met in 1816 in [[Corydon, Indiana|Corydon]]. The [[Constitution of Indiana|state's first constitution]] was drawn up on June 10, and elections were held in August to fill the offices of the new state government. In November of that year the constitution was approved by Congress and the territorial government was dissolved, ending the existence of the Indiana Territory and replacing it with the State of Indiana.<ref>Funk, p. 35</ref><ref name =ihc3>{{cite web|url=http://www.centerforhistory.org/indiana_history_main3.html|publisher=Indiana Center For History|title=''Indiana History Chapter three''|accessdate=2008-05-17}}</ref> |

||

Jennings and his supporters were able to take control of the convention and Jennings was elected president of the convention. Other notables at the convention included Dennis Pennington, [[Davis Floyd]], and [[William Hendricks]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.in.gov/history/6117.htm|title= ''List of Delegates at first Constitutional Convention''|publisher=In.gov|author=Indiana Historical Bureau|accessdate=2008-05-18}}</ref> Pennington and Jennings were at the forefront of the effort to prevent slavery from entering Indiana and sought to create a constitutional ban on it. Pennington was quoted as saying "Let us be on our guard when our convention men are chosen that they be men opposed to slavery". They succeeded in their goal and a ban was placed in the new constitution.<ref>Henderson, p. 193</ref> That same year Indiana statehood was approved by Congress. Jonathan Jennings, whose motto was "No slavery in Indiana", was elected governor of the state defeating Thomas Posey 5,211 to 3,934 votes.<ref name = w163>Woollen, p. 163</ref> Jennings served two terms as governor and then went on to represent the state in congress for another 18 years. Upon election, Jennings declared Indiana a free state.<ref name = w163/> The abolitionists won their final victory in the 1820 [[Indiana Supreme Court]] case of [[Polly v. Lasselle]] that freed all the remaining slaves in the state.<ref>Dunn, pp. 346—348</ref> |

Jennings and his supporters were able to take control of the convention and Jennings was elected president of the convention. Other notables at the convention included Dennis Pennington, [[Davis Floyd]], and [[William Hendricks]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.in.gov/history/6117.htm|title= ''List of Delegates at first Constitutional Convention''|publisher=In.gov|author=Indiana Historical Bureau|accessdate=2008-05-18}}</ref> Pennington and Jennings were at the forefront of the effort to prevent slavery from entering Indiana and sought to create a constitutional ban on it. Pennington was quoted as saying "Let us be on our guard when our convention men are chosen that they be men opposed to slavery". They succeeded in their goal and a ban was placed in the new constitution.<ref>Henderson, p. 193</ref> That same year Indiana statehood was approved by Congress. Jonathan Jennings, whose motto was "No slavery in Indiana", was elected governor of the state defeating Thomas Posey 5,211 to 3,934 votes.<ref name = w163>Woollen, p. 163</ref> Jennings served two terms as governor and then went on to represent the state in congress for another 18 years. Upon election, Jennings declared Indiana a free state.<ref name = w163/> The abolitionists won their final victory in the 1820 [[Indiana Supreme Court]] case of [[Polly v. Lasselle]] that freed all the remaining slaves in the state.<ref>Dunn, pp. 346—348</ref> |

||

| Line 135: | Line 135: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

The [[National Road]] was connected to Indianapolis in 1829, connecting Indiana to the [[Eastern United States]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.centerforhistory.org/indiana_history_main4.html|publisher=Indiana Center For History|title=Indiana History Chapter Four|accessdate=2008-05-17}}</ref> It was also about this time that citizens of Indiana became known as [[Hoosier]]s and the state took on the motto "Crossroads of America".<ref group=n>The origin of the word Hoosier is unknown</ref> In 1832, construction began on the [[Wabash and Erie Canal]], a project connecting the waterways of the Great Lakes to the Ohio River. The canal system was soon made obsolete by [[Rail transport in the United States|railroads]]. These developments in transportation served to economically connect Indiana to the Northern [[East Coast of the United States|East Coast]], rather than relying solely on the natural waterways which connected Indiana to Mississippi River and [[Gulf Coast of the United States|Gulf Coast states]].<ref>Nevins, pp. 206, 227</ref><ref group=n>Map on page Nevins, p. 209 shows that as of 1859, no Railroad crossed the Mississippi or Ohio Rivers.</ref> |

The [[National Road]] was connected to Indianapolis in 1829, connecting Indiana to the [[Eastern United States]].<ref name = inh4>{{cite web|url=http://www.centerforhistory.org/indiana_history_main4.html|publisher=Indiana Center For History|title=Indiana History Chapter Four|accessdate=2008-05-17}}</ref> It was also about this time that citizens of Indiana became known as [[Hoosier]]s and the state took on the motto "Crossroads of America".<ref group=n>The origin of the word Hoosier is unknown</ref> In 1832, construction began on the [[Wabash and Erie Canal]], a project connecting the waterways of the Great Lakes to the Ohio River. The canal system was soon made obsolete by [[Rail transport in the United States|railroads]]. These developments in transportation served to economically connect Indiana to the Northern [[East Coast of the United States|East Coast]], rather than relying solely on the natural waterways which connected Indiana to Mississippi River and [[Gulf Coast of the United States|Gulf Coast states]].<ref>Nevins, pp. 206, 227</ref><ref group=n>Map on page Nevins, p. 209 shows that as of 1859, no Railroad crossed the Mississippi or Ohio Rivers.</ref> |

||

In 1831, construction on the third [[Indiana Statehouse|state capitol building]] began. This building, designed by the firm of [[Ithiel Town]] and [[Alexander Jackson Davis]], had a design inspired by the [[Greece|Greek]] [[Parthenon]] and opened in 1841. It was first statehouse that was built and used exclusively by the state government.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.in.gov/idoa/2550.htm|title=''The State House Story''|publisher=IN.gov|author=Indiana Historical Bureau|accessdate=2008-05-17}}</ref> |

In 1831, construction on the third [[Indiana Statehouse|state capitol building]] began. This building, designed by the firm of [[Ithiel Town]] and [[Alexander Jackson Davis]], had a design inspired by the [[Greece|Greek]] [[Parthenon]] and opened in 1841. It was first statehouse that was built and used exclusively by the state government.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.in.gov/idoa/2550.htm|title=''The State House Story''|publisher=IN.gov|author=Indiana Historical Bureau|accessdate=2008-05-17}}</ref> |

||

| Line 163: | Line 163: | ||

In 1832, the state began construction on the [[Wabash and Erie Canal]]. The canal was started at [[Lake Erie]], passed through Fort Wayne, and connected to the [[Wabash River]]. This new canal made water transport possible from New Orleans to Lake Erie on a internal route rather than sailing around the whole of the Eastern United States and entering through Canada. Other canal projects were started, but all were abandoned before completion due to the states foundering credit after the devaluation of the bonds.<ref>Dunn, p. 429</ref> |

In 1832, the state began construction on the [[Wabash and Erie Canal]]. The canal was started at [[Lake Erie]], passed through Fort Wayne, and connected to the [[Wabash River]]. This new canal made water transport possible from New Orleans to Lake Erie on a internal route rather than sailing around the whole of the Eastern United States and entering through Canada. Other canal projects were started, but all were abandoned before completion due to the states foundering credit after the devaluation of the bonds.<ref>Dunn, p. 429</ref> |

||

The first railroad in Indiana was built in [[Shelbyville, Indiana|Shelbyville]] in the late 1830s. The first major line was completed in 1847, connecting [[Madison, Indiana| Madison]] with Indianapolis. By the 1850s, the railroad began to become popular in Indiana. The railroad brought major changes to Indiana and enhanced the states economic growth.<ref |

The first railroad in Indiana was built in [[Shelbyville, Indiana|Shelbyville]] in the late 1830s. The first major line was completed in 1847, connecting [[Madison, Indiana| Madison]] with Indianapolis. By the 1850s, the railroad began to become popular in Indiana. The railroad brought major changes to Indiana and enhanced the states economic growth.<ref name = inh4/> Although Indiana's natural waterways connected it to the South via cities such as St. Louis and New Orleans, the new rail lines ran East-West, and connected Indiana with the economies of the northern states.<ref>Nevins, pp. 195-196.</ref> As late as mid-1859, no rail line yet bridged the Ohio or Mississippi rivers.<ref>Nevins, pp. 209</ref> Because of an increased demand on the states resources and the embargo against the [[Confederate States of America|Confederacy]], the rail system was mostly completed by the end of the [[American Civil War]]. |

||

==Civil War== |

==Civil War== |

||

| Line 238: | Line 238: | ||

{{see also|Indiana Klan}} |

{{see also|Indiana Klan}} |

||

The war-time economy provided a boom to Indiana's industry and agriculture, which led to more [[urbanization]] throughout the 1920s. By 1925 Indiana had passed a great milestone: more workers were employed in industry than in agriculture. Indiana's greatest industries were [[steel]] production, [[iron]], automobiles, and railroad cars.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.centerforhistory.org/indiana_history_main9.html|publisher= Indiana Center for History|title= Indiana History Chapter Nine|accessdate=2008-05-17}}</ref> |

The war-time economy provided a boom to Indiana's industry and agriculture, which led to more [[urbanization]] throughout the 1920s. By 1925 Indiana had passed a great milestone: more workers were employed in industry than in agriculture. Indiana's greatest industries were [[steel]] production, [[iron]], automobiles, and railroad cars.<ref name = ihc9>{{cite web|url=http://www.centerforhistory.org/indiana_history_main9.html|publisher= Indiana Center for History|title= Indiana History Chapter Nine|accessdate=2008-05-17}}</ref> |

||

Scandal erupted across the state in 1925 when it was discovered that over half the seats in the General Assembly were controlled by the [[Klu Klux Klan]]. During the 1925 General Assembly session [[Grand Dragon]] [[D. C. Stephenson]] boasted "I am the law in Indiana." Stephenson was convicted for the [[homicide|murder]] of [[Madge Oberholtzer]] that year and sentenced to [[life in prison]]. After Governor [[Edward Jackson]], who Stephenson helped elect, refused to pardon him, Stephenson began to name many of his co-conspirators leading to a string of arrests and indictments against leading Hoosiers including the governor, mayor of Indianapolis, the attorney general, and many others. The crackdown effectively rendered the Klan powerless.<ref>Lutholtz, p. 43,83}</ref> |

Scandal erupted across the state in 1925 when it was discovered that over half the seats in the General Assembly were controlled by the [[Klu Klux Klan]]. During the 1925 General Assembly session [[Grand Dragon]] [[D. C. Stephenson]] boasted "I am the law in Indiana." Stephenson was convicted for the [[homicide|murder]] of [[Madge Oberholtzer]] that year and sentenced to [[life in prison]]. After Governor [[Edward Jackson]], who Stephenson helped elect, refused to pardon him, Stephenson began to name many of his co-conspirators leading to a string of arrests and indictments against leading Hoosiers including the governor, mayor of Indianapolis, the attorney general, and many others. The crackdown effectively rendered the Klan powerless.<ref>Lutholtz, p. 43,83}</ref> |

||

| Line 246: | Line 246: | ||

During the 1930s, Indiana, like the rest of the nation, became caught up in the [[Great Depression]]. The economic downturn had a wide-ranging negative impact on Indiana. Much of the movement toward urbanization in the 1920s was lost. The situation was aggravated by the [[Dust Bowl]] which caused an influx of immigrants from the west. The administration of Governor [[Paul V. McNutt]] struggled to build from scratch a state funded welfare system to help the overwhelmed private charities. During his administration, spending and taxes were both cut drastically in response to the depression and the state government was completely reorganized. McNutt also ended prohibition in the state and enacted the state's first income tax. On several occasions, he declared martial law to put an end to worker strikes.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.countyhistory.com/doc.gov/037.htm|title= Paul V. McNutt|publisher=County History Preservation Society|author=Ronald Branson|accessdate=2008-05-24}}</ref> |

During the 1930s, Indiana, like the rest of the nation, became caught up in the [[Great Depression]]. The economic downturn had a wide-ranging negative impact on Indiana. Much of the movement toward urbanization in the 1920s was lost. The situation was aggravated by the [[Dust Bowl]] which caused an influx of immigrants from the west. The administration of Governor [[Paul V. McNutt]] struggled to build from scratch a state funded welfare system to help the overwhelmed private charities. During his administration, spending and taxes were both cut drastically in response to the depression and the state government was completely reorganized. McNutt also ended prohibition in the state and enacted the state's first income tax. On several occasions, he declared martial law to put an end to worker strikes.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.countyhistory.com/doc.gov/037.htm|title= Paul V. McNutt|publisher=County History Preservation Society|author=Ronald Branson|accessdate=2008-05-24}}</ref> |

||

During the Great Depression, [[unemployment]] exceeded 25% statewide. [[Southern Indiana]] was particularly hard hit where unemployment topped 50% during the worst years. The [[Works Progress Administration]] (WPA) began its operations in Indiana in July 1935. By October of that year, 74,708 Hoosiers were employed by the agency. In 1940, there were still 64,700 working for agency. The majority of these workers were employed to improve the state's roads, bridges, flood control projects, water treatment plants, some indexed libraries, and even create murals for post offices—every community had a project to work on.<ref |

During the Great Depression, [[unemployment]] exceeded 25% statewide. [[Southern Indiana]] was particularly hard hit where unemployment topped 50% during the worst years. The [[Works Progress Administration]] (WPA) began its operations in Indiana in July 1935. By October of that year, 74,708 Hoosiers were employed by the agency. In 1940, there were still 64,700 working for agency. The majority of these workers were employed to improve the state's roads, bridges, flood control projects, water treatment plants, some indexed libraries, and even create murals for post offices—every community had a project to work on.<ref name = ihc9/> |

||

During the 1930s many of Indiana's prominent businesses collapsed, several railroads went bankrupt, and numerous banks folded.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.indianahistory.org/ihs_press/web_publications/railroad/keenan.html|title= ''The Fight for Survival: The Cincinnati & Lake Erie and the Great Depression''|author=Keenan, Jack |publisher=Indiana Historical Society|accessdate=2008-05-23}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.indianahistory.org/hbr/business_pdf/star_bank_eastern.pdf|title=''Star Bank, National Association, Eastern Indiana''|publisher=Indiana Historical Society|accessdate=2008-05-21|format=PDF}}</ref> Manufacturing came to an abrupt halt or was severely cut back due the dwindling demand for products. The depression continued to negatively affect Indiana until World War II, and the effects continued to be felt for many years thereafter. |

During the 1930s many of Indiana's prominent businesses collapsed, several railroads went bankrupt, and numerous banks folded.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.indianahistory.org/ihs_press/web_publications/railroad/keenan.html|title= ''The Fight for Survival: The Cincinnati & Lake Erie and the Great Depression''|author=Keenan, Jack |publisher=Indiana Historical Society|accessdate=2008-05-23}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.indianahistory.org/hbr/business_pdf/star_bank_eastern.pdf|title=''Star Bank, National Association, Eastern Indiana''|publisher=Indiana Historical Society|accessdate=2008-05-21|format=PDF}}</ref> Manufacturing came to an abrupt halt or was severely cut back due the dwindling demand for products. The depression continued to negatively affect Indiana until World War II, and the effects continued to be felt for many years thereafter. |

||

Revision as of 04:16, 12 October 2008

The history of Indiana is an examination of the history, social activity, and development of the inhabitants and institutions within the borders of modern Indiana, a U.S. state in the Midwest. Indiana was inhabited by migratory tribes of Native Americans possibly as early as 8000 BCE. These tribes succeeded one another in dominance for several thousand years. The region entered recorded history when the first Europeans came to Indiana and claimed the territory for Kingdom of France during the 1670s. At the conclusion of the French and Indian War and one hundred years of French rule, the region came under the control of the Kingdom of Great Britain. British control was short-lived, as the region was transferred to the newly formed United States at the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War only twenty years later.

At the time the United States took possession of the Northwest Territory, there were only two permanent European settlements in the region that would later become Indiana. The United States Congress immediately set to work to develop the Northwest. In 1800, the Indiana Territory was established and steadily settled until it was admitted to the Union in 1816 as the nineteenth state. Following statehood, the new government set out on an ambitious plan to transform Indiana from a wilderness frontier into a developed, well populated, and thriving state. The state's founders initiated a program that led to the construction of roads, canals, railroads, and state funded public schools. During the 1850s, the state's population grew to exceed one million and the ambitious program of the state founders was finally realized.

Indiana became politically influential and played an important role in the affairs of the nation during the American Civil War. As the first western state to mobilize for the war, Indiana's soldiers were present in almost every engagement during the war. After the Civil War, Indiana remained important nationally as it became a critical swing state in U.S. Presidential elections, and decided control of the federal government for three decades. During the early 20th century, Indiana developed into a strong manufacturing state, then experienced setbacks during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The state also saw many developments with the construction of Indianapolis Motor Speedway, the takeoff of the auto industry in the state, substantial urban growth, and two major United States wars. Economic recovery began during World War II and the state continued to enjoy substantial growth. During the second half the of the 20th century, Indiana became a leader in the pharmaceutical industry due to the many innovations of companies like Eli Lilly.

Early civilizations

Following the retreat of the last glacial period, Indiana was dominated by Spruce and pine forests, and was home to animals such as mastodon, caribou, and Saber-toothed cat.[1] Southern Indiana remained undamaged by glaciers, leaving plants and animals which could sustain human communities.[2] Indiana's earliest known inhabitants were Paleo-Indians. Evidence exists that humans were in Indiana as early as the Archaic stage (8000–6000 BCE).[3] Hunting camps of the nomadic Clovis culture have been found in Indiana.[4] Carbon dating of artifacts found in Wyandotte Caves shows that humans mined flint there as early 2000 BCE.[5] These nomads may have enjoyed the large supply of freshwater mussels in Indiana's streams, and could have started the shell mounds found throughout southern Indiana.[5]

The Early Woodland period in Indiana is generally dated between 1000 BCE and 200 CE. The society of this time is known as the Adena culture, named for the estate in Ohio where it was first discovered.[6] The Adena culture is noted for domesticating some plants and for using pottery—large cultural advances over the Clovis culture. The Early Woodland period also saw the introduction of early burial mounds, and some of the oldest mounds in Indiana, including the oldest in Mounds State Park, date from this era.[7]

Humans of the Middle Woodland period, of the Hopewell culture, may have been in Indiana as early as 200 BCE. The Hopewells were the first culture to create permanent settlements in Indiana. Around 1 CE, the Hopewells mastered agriculture and grew crops of sunflowers and squash, beginning their development into an agrarian civilization. Around 200 CE, the Hopewells began to construct mounds that are believed to have been used for ceremonial and burial purposes. Most modern knowledge of the Hopewells has come from the excavation of these mounds. The artifacts in the mounds show the Hopewells in Indiana were connected by trade to many other native tribes as far away as Central America.[8] At sometime around 400 CE, the Hopewell culture went into decline for unknown reasons and disappeared completely by 500 CE.[9]

The Late Woodland era is generally marked around 600 CE until the arrival of Europeans. This is considered a period of rapid cultural change. One of the new developments—which has yet to be explained—is the arrival of masons who built a number of large, stone forts, many of which overlook the Ohio River. Romantic legend credits these forts to the arrival of Welsh Indians, centuries before Christopher Columbus arrived in the Caribbean.[10] Most cultural development, however, is credited to the arrival of the Mississippians.[11]

Mississippians

Evidence suggests that after the collapse of the Hopewells, Indiana had a low population until the rise of the Mississippian culture around 900. The Ohio River Valley was very heavily populated by the Mississippians from about 1100 to 1450. The Mississippian settlements, like the Hopewells before them, were also known for their ceremonial mounds, many of the mounds are still visible. The Mississippian mounds were constructed on a grander scale than the mounds built by the Hopewells. The Mississippians were agrarian and were responsible for the domestication of maize. The bow and arrow and copper working were also perfected during the Mississippians' years of prevalence.[12]

Mississippian society was highly developed, with cities being home to as many as thirty-thousand inhabitants. Mississippian cities were typically near rivers and included a large central mound, several smaller mounds, an open courtyard, and the city was usually enclosed by walls. A major settlement known as Angel Mounds is east of present day Evansville.[13] Mississippian houses were generally square, with plastered walls and thatched roofs.[14] The Mississippians disappeared in the mid-fifteenth century for reasons that remain unclear. Their disappearance in Indiana occurred about two-hundred years before the Europeans first entered what would become modern Indiana. Mississippian culture marked the high point of native development in Indiana.[12]

It was also during this period that the American Bison began a periodic East-West trek through Indiana, crossing at the Falls of the Ohio and over the Wabash River near Vincennes.[15] These herds not only became important to civilizations in Southern Indiana, but also wore a well-established Buffalo Trace that would later be used by pioneers moving West.

European contact

Sometime before 1600, a major war broke out in eastern North America that later became known as the Beaver Wars. The five Iroquois tribes confederated to battle against their neighbors. The Iroquois were opposed by a confederation of primarily Algonquin tribes including the Shawnee, Miami, Wea, Pottawatomie, and the Illinois.[16] These tribes were significantly less advanced than the Mississippian culture that preceded them. The tribes were semi-nomadic, returned to the use of stone tools, and did not follow the large scale construction and agrarian ways of their Mississippian predecessors. The war continued for at least a century as the Iroquois' sought to dominate the fur trade, a goal they achieved for several decades. In the course of the war, the Iroquois drove their neighboring tribes to the south and west.[17][18] The war caused several tribes, including the Shawnee, to migrate into Indiana where they attempted to resettle in land belonging to the Miami. The Iroquois gained the upper hand after they were supplied with firearms by the Dutch in New Netherlands and later by the English. With their new found superior arms the Iroquois subjugated at least thirty other tribes and nearly destroyed others in northern Indiana.[19]

When the first Europeans entered Indiana, the region was in the final years of the conflict. The French attempted to trade with the Algonquian tribes in Indiana, including selling them firearms. This brought on the wrath of the Iroquois who destroyed a French outpost in Indiana in retaliation. Appalled by the Iroquois, the French continued to supply the western tribes with firearms and openly allied with the Algonquian tribes.[20][21] A major battle, and a turning point in the conflict, occurred near modern South Bend, where the Miami and their allies repulsed a large Iroquois force in an ambush.[22] With the firearms they received from the French the odds had evened, and the war eventually ended with the Great Peace of Montreal in 1701. Both of the Indian confederacies were left exhausted having suffered very heavy casualties and much of Ohio, Michigan and Indiana was left depopulated as many of the tribes had fled to the west.[23]

The Indian Nations that are more commonly associated with Indiana, like the Miami and Pottawatomie, returned to Indiana in the late 17th century following the war.[24][25] Other tribes, like the Delaware, were pushed westward by European colonists. The Miami invited the Delaware to settle on the White River in about 1770.[26] [n 1] The Shawnee arrived even later.[27] These four nations were later to be participants in the Sixty Years' War, a struggle between Native Nations and White Nations for control of the Great Lakes region. The first known deaths of Europeans by Indians in Indiana occurred in 1752, when five French fur traders were attacked and killed by some Piankeshaw Indians near the Vermillion River.[28]

Colonial rule

The first Europeans entered Indiana in the 1670s and added the region to New France. The quickest route connecting the New France districts of Canada and Louisiana ran through Indiana, and the Terre Haute highlands were once considered the border between the two districts.[29] This made the Indiana region a vital part of French holdings for communications and trade. This also made Indiana important for the British to control if they were to halt French expansion.[30] Only one permanent European settlement, Vincennes, was established in Indiana during European rule, but the territory was inhabited by numerous native tribes.[31]

France

French fur traders from Canada were the first Europeans to enter Indiana.[32] The first European outpost within modern Indiana was Tassinong, a French trading post established in 1673 near the Kankakee River.[n 2] French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle came to the area in 1679, claiming it for the King Louis the XIV of France. La Salle came to explore a portage between the St. Joseph and Kankakee rivers,[33] and Father Ribourde, who travelled with La Salle, marked trees along the way that would survive long enough to be photographed.[34] In 1681, La Salle negotiated a treaty between the Illinois and Miami nations in common defense against the Iroquois.[35]

A further exploration of Indiana led to an important trade route being established using the Maumee and Wabash rivers to connect Canada and Louisiana. The French established a series of forts and outposts in Indiana to defend against the westward expansion of the British colonies and to encourage trade with the native tribes. The tribes benefited from the trade with the French, and were able to procure metal tools, cooking utensils, and other utilitarian items in exchange for animal pelts. The French built Fort Miamis in the Miami town of Kekionga (modern Fort Wayne, Indiana). France assigned Jean Baptiste Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes, as the first agent to the Miami at Kekionga.[36]

In 1717, François-Marie Picoté de Belestre[n 3] established the post of Ouiatenon (modern Lafayette, Indiana) to discourage the Wea from moving into the British sphere of influence.[37] In 1732, François-Marie Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes established a similar post near the Piankeshaw in the town that still bears his name. Although these forts were garrisoned by men sent from New France, there was no official attempted to form permanent settlements in Indiana. Vincennes was the only outpost to maintain a permanent European presence until the modern day.[38]

Jesuit priests accompanied many of the French soldiers into Indiana. In an attempt to convert the natives to Christianity. The Jesuits conducted missionary works, lived among the natives, and accompanied them on hunts and migrations. Gabriel Marest was teaching among the Kaskaskia as early as 1712. The missionaries came to have great influence among the natives and played an important role in keeping the native tribes allied with the French.[39]

The first European war to affect what would become Indiana began in 1689. King William's War had little impact on the region, but some of the native tribes took part in minor raiding near the British colonies. The second conflict to occur was Queen Anne's War and lasted from 1740 to 1748. Although no battles occurred in the region during the second conflict, the French convinced many of the regions Native American tribes to join in raids against the British colonies. The conclusion of Queen Anne's war saw French control of Canada compromised, and that would lead to Canada's fall to Britain in the next conflict.[40]

During the French and Indian War, the British challenged the French control in the region again. Although no pitched battles occurred in Indiana, the native tribes still supported the French.[41] At the beginning of the war, the tribes sent large groups of warriors to support the French in resisting the British advance and to take part in raiding on the British colonies. The British initially had several setbacks in their attempt to campaign westward because of the native resistance, but they were eventually able to overcome the natives.[42] Using Fort Pitt as a forward base, Robert Rogers drove deep into the frontier and captured Fort Detroit. Robert's Rangers moved south from Detroit and captured many of the key French outposts in Indiana including Fort Miamis and Fort Vincennes.[43] As the war progressed, the French lost control of Canada after the fall of Montreal and were no longer able to support the hinterland and much of the territory was captured by the British, including all of Indiana. The French were entirely forced out of Indiana by 1761.[44] Following the French expulsion, the native tribes under Chief Pontiac confederated in an attempt to rebel against the British, without French assistance. While Pontiac was besieging Fort Detroit other tribes in Indiana rose up against the British forcing them to surrender Fort Miamis and Fort Ouiatenon.[45] In 1763, while Pontiac was still resisting the British, the French signed the Treaty of Paris which gave control of all of Indiana to the British.[46]

Great Britain

When the British gained ownership of Indiana, the entire region was in the middle of Pontiac's Rebellion. Over the next year, British officials negotiated with the various tribes until Chief Pontiac had lost most of his allies. Finally on July 25, 1766 Pontiac made peace with British. As a concession to Pontiac, Great Britain issued a proclamation that territory west of the Appalachian Mountains was to be reserved for Native Americans.[47] Despite the treaty, Pontiac was still considered a threat to the British, but after he was murdered on April 20, 1769, the region saw several years of peace.[48]

After establishing peace with the natives, many of the remote trading posts and forts were abandoned by the British. Fort Miamis was still maintained for several years because it was considered to be "of great importance", but even it was eventually abandoned.[49] The Jesuit priests were expelled and no provisional government was established; the British hoped that the French residents would leave. Many did leave, but the British gradually became more accommodating to the French residents who remained and carried on the vital trade with the native Native Americans.[50]

In 1768 a treaty was negotiated between the several of the British colonies and the Iroqois. The Iroquois sold their claim the northwest to the colonies as part of the treaty, and the company created to hold that claim was named the Indiana Land Company, the first recorded use of the word Indiana. The claim was disputed by Virginia, who had already laid claim to the land.[51] In 1773, the territory of Indiana was given to the Province of Quebec to appease its French population. The Quebec Act was listed as one of the Intolerable Acts that the Thirteen Colonies cited as a reason for the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. The thirteen colonies thought themselves entitled to the territory for their support during the war, rather than it being awarded to the enemy the colonies had been fighting.[52]

Although the United States gained official possession of the region following the war, British influence on its Native American allies remained strong in northern Indiana, especially around Fort Detroit. This waned considerably after the Northwest Indian War and the ratification of the Jay Treaty, but the British were not fully expelled from the area until the conclusion of the War of 1812.[53]

United States

After the outbreak of the American Revolution, George Rogers Clark was sent from Virginia to enforce its claim to much of the land in the northwest.[54] In July 1778, Clark and about 175 men crossed the Ohio River and took control of Kaskaskia, Vincennes, and several other villages in British territory. The occupation was accomplished without firing a shot because Clark carried letters from the French ambassador stating French support of the Americans. This made most of the French and Native American inhabitants unwilling to take up arms on behalf of the British.[55]

The fort at Vincennes, renamed Fort Sackville by the British, had been abandoned years earlier and there was no garrison to defend the post. Captain Leonard Helm became the first American commandant at Vincennes. To counter Clark's advance, the British under Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton reoccupied Vincennes with a small force. In February 1779, Clark arrived at Vincennes in a surprise winter expedition and retook the town, capturing Hamilton in the process. This winter expedition secured most of southern Indiana for the United States.[56]

In 1780, emulating Clark's success at Vincennes, French officer Augustin de La Balme organized a militia force of French residents to capture Fort Detroit. While marching to Detroit, the force stopped to sack Kekionga. The delay proved fatal when the expedition met the warriors of the Miami tribe under Miami Chief Little Turtle along the Eel River, and the entire force was killed or captured. Clark again organized an assault on Fort Detroit in 1781, but it was aborted when Chief Joseph Brant captured a significant part of Clark's army at a battle known as Lochry's Defeat, near present-day Aurora, Indiana.[57]

Other minor skirmishes occurred in Indiana, including the battle at Petit Fort in 1780.[58] At the end of the war in 1783, Britain ceded the entire trans-Allegheny region to the United States, including Indiana, in the peace treaty negotiated in Paris.[59]

Clark's militia was under the authority of the State of Virginia, and although a continental flag was flown over Fort Sackville, the area was governed as Virginian territory until the state gifted it to the United States federal government in 1784.[60] Clark was awarded large tracts of land in southern Indiana for his services in the war and today Clark County is named in his honor.[61]

Indiana Territory

The Northwest Territory was formed by the Congress of the Confederation on July 13, 1787, and included all land between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River, the Great Lakes and the Ohio River. This single territory became the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and eastern Minnesota. The act established an administration to oversee the territory and had the land surveyed in accordance with The Land Ordinance of 1785.[62] At the time the territory was created, there where only two American settlements in what would become Indiana, Vincennes and Clark's Grant. The entire population of the northwest was under 5,000 Europeans. The Native American population was estimated to be near 20,000, but may have been as high as 75,000.[63]

In 1785, the Northwest Indian War began. In an attempt to end the native rebellion, the Miami town of Kekionga was attacked unsuccessfully by General Josiah Harmar and Northwest Territory Governor Arthur St. Clair. St. Clair's defeat is the worst defeat of the U.S. army by Native Americans in history leaving almost the entire army dead or captured.[64] The defeat led to the appointment of General "Mad Anthony" Wayne who organized the Legion of the United States and defeated a Native American force at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. In 1795 the Treaty of Greenville was signed and a small part of eastern Indiana was opened for settlement. Fort Miamis at Kekionga was occupied by the United States, who rebuilt it as Fort Wayne. After the treaty, the powerful Miami nation considered themselves allies with the United States.[65] Native Americans were victorious in 31 of the 37 recorded incidents involving white settlers during the 18th century.[66]

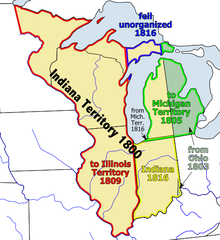

On July 4, 1800, the Indiana Territory was established out of Northwest Territory in preparation for Ohio's statehood.[67] The Indiana Land Company, who still held claim to Indiana, had been dissolved by a United States Supreme Court decision in 1798. The name Indiana meant "Land of the Indians", and referred to the fact that most of the area north of the Ohio River was still inhabited by Native Americans. (Kentucky, South of the Ohio River, had been a traditional hunting ground for tribes that resided north of the river, and early American settlers in Kentucky referred to the North bank as the land of the Indians.) Although the company's claim was extinguished, Congress used their name for the new territory.[51] The Indiana Territory contained present day Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and part of Minnesota.[68] Those areas were separated out in 1805 and 1809. The first Governor of the Territory was William Henry Harrison, who served from 1800 until 1813. Harrison County was named in honor of Harrison, who later become the ninth President of The United States. Harrison was succeeded by Thomas Posey in who served from 1813 until 1816.[69]

The first capital was established in Vincennes where it remained for thirteen years. After the territory was reorganized in 1809, the legislature made plans to move the capital to Corydon to be more centralized with the population. Corydon was established in 1808 on land donated by William Henry Harrison. The new capitol building was finished in 1813 and the government relocated.[70][71]

As the population of the territory grew, so did the people's exercise of their freedoms. In 1809, the territory was granted permission to fully elect its own legislature for the first time.[72] Prior to that time, the legislature had been appointed by Governor Harrison. Slavery in Indiana was the major issue in the territory at the time and the anti-slavery party won a strong majority in the first election.[73] Governor Harrison found himself at odds with and overruled by the new legislature which proceeded to overturn the indenturing and pro-slavery laws he had enacted. Slavery remained the defining issue in the state for the decades to follow.[74][75]

War of 1812

The first major event in the territory was the resumption of hostilities with the Indians. There are 58 recorded incidents between Native Americans and the United States in Indiana during the 19th century, and 43 of these are Indian victories, and eight of the American victories only involved burning deserted villages.[76]

Unhappy with their treatment since the peace of 1795, the native tribes, let by the Shawnee Chief Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa, rose up against the Americans. Tecumseh's War started in 1811 when General William Henry Harrison led his army to rebuff the aggressive movements of Tecumseh's confederation.[77] The war continued until the Battle of Tippecanoe which firmly ending the Native American uprising and allowed the Americans to take full control of all of Indiana. The Battle earned Harrison national fame, and the nickname "Old Tippecanoe".[78]

The war between Tecumseh and Harrison merged with the War of 1812 when the remnants of Indian Confederation allied with the British in Canada. The Battle of Fort Harrison is considered to be the United States' first land victory during the war.[79] Other battles that occurred in the modern state of Indiana include the Siege of Fort Wayne, the Pigeon Roost Massacre and the Battle of the Mississinewa. The Treaty of Ghent, signed in 1814, ended the War and relieved American settlers from their fears of the nearby British and their Indian allies.[80] For the first time, the United States had firm control over the Indiana Territory.

Statehood

In 1812, Jonathan Jennings defeated Harrison's chosen candidate and became the territory's representative to Congress.[81] Jennings used his position there to speed up Indiana's path to statehood by immediately introducing legislation to grant Indiana statehood, even though the population of the entire territory was under 25,000. Jennings did so against the wishes of incoming governor Thomas Posey. No action was taken on the legislation at the time though because of the outbreak of the War of 1812.[82]

Posey had created a rift in the politics of the territory by refusing to reside in the capitol of Corydon, but instead living in Jeffersonville to be closer to his doctor.[83][n 4] He further complicated matters by being a supporter of slavery, much to the chagrin of opponents like Jennings, Dennis Pennington, and others who dominated the Territorial Legislature and who sought to use the bid for statehood to permanently end slavery in the territory.[84]

Founding

In February 1815, the United States House of Representatives began debate on granting Indiana Territory statehood. In early 1816, the Territory approved a census and Pennington was named to be the census enumerator. The population of the territory was found to be 63,897,[85] above the limit required for statehood that was stated in the Northwest Ordinance. On May 13, 1816, the Enabling Act was passed and the state was granted permission to form a government subject to the approval of Congress.[86] A constitutional convention met in 1816 in Corydon. The state's first constitution was drawn up on June 10, and elections were held in August to fill the offices of the new state government. In November of that year the constitution was approved by Congress and the territorial government was dissolved, ending the existence of the Indiana Territory and replacing it with the State of Indiana.[87][88]

Jennings and his supporters were able to take control of the convention and Jennings was elected president of the convention. Other notables at the convention included Dennis Pennington, Davis Floyd, and William Hendricks.[89] Pennington and Jennings were at the forefront of the effort to prevent slavery from entering Indiana and sought to create a constitutional ban on it. Pennington was quoted as saying "Let us be on our guard when our convention men are chosen that they be men opposed to slavery". They succeeded in their goal and a ban was placed in the new constitution.[90] That same year Indiana statehood was approved by Congress. Jonathan Jennings, whose motto was "No slavery in Indiana", was elected governor of the state defeating Thomas Posey 5,211 to 3,934 votes.[91] Jennings served two terms as governor and then went on to represent the state in congress for another 18 years. Upon election, Jennings declared Indiana a free state.[91] The abolitionists won their final victory in the 1820 Indiana Supreme Court case of Polly v. Lasselle that freed all the remaining slaves in the state.[92]

As the northern tribal lands gradually opened to white settlement, Indiana's population rapidly increased and the center of population shifted continually northward.[93] Indianapolis was selected to be the site of the new state capital in 1820 because of its central position within the state. Jeremiah Sullivan, a justice of the Indiana Supreme Court, invented the name Indianapolis by joining Indiana with polis, the Greek word for city; literally, Indianapolis means "Indiana City".[94] The city was founded on the White River under the incorrect assumption that the river could serve as a major transportation artery; however, the waterway was too sandy for trade. In 1825, Corydon was finally replaced as the seat of government in favor of Indianapolis. At the time, Indianapolis was in the wilds and 60 miles (97 km) from the nearest settlement. The government established itself in the Marion County Courthouse as the second state capital.[93]

Early development

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 2,632 | — | |

| 1810 | 24,520 | 831.6% | |

| 1820 | 147,178 | 500.2% | |

| 1830 | 343,031 | 133.1% | |

| 1840 | 685,866 | 99.9% | |

| 1850 | 988,416 | 44.1% | |

| 1860 | 1,350,428 | 36.6% | |

| [95] | |||

The National Road was connected to Indianapolis in 1829, connecting Indiana to the Eastern United States.[96] It was also about this time that citizens of Indiana became known as Hoosiers and the state took on the motto "Crossroads of America".[n 5] In 1832, construction began on the Wabash and Erie Canal, a project connecting the waterways of the Great Lakes to the Ohio River. The canal system was soon made obsolete by railroads. These developments in transportation served to economically connect Indiana to the Northern East Coast, rather than relying solely on the natural waterways which connected Indiana to Mississippi River and Gulf Coast states.[97][n 6]

In 1831, construction on the third state capitol building began. This building, designed by the firm of Ithiel Town and Alexander Jackson Davis, had a design inspired by the Greek Parthenon and opened in 1841. It was first statehouse that was built and used exclusively by the state government.[98]

The state suffered from financial difficulties during its first three decades. Jonathan Jennings attempted to begin a period of internal improvements. Among his projects, the Indiana Canal Company was reestablished to build a canal around the Falls of the Ohio. The Panic of 1819 caused the state's only two banks to fold, hurting Indiana's credit halting the projects and hampered the start of any new projects until the 1830s, after the repair of the state's finances during the terms of William Hendricks and Noah Noble. Beginning in 1831, large scale plans for statewide improvements were set into motion. Overspending on the internal improvements led to a large deficit that had to be funded by state bonds through the newly created Bank of Indiana and sale of over nine million acres (36,000 km²) of public land. By 1841 the debt had become unmanageable.[99] Having burrowed over $13 million, the equivalent to the state's first fifteen years of tax revenue, the government was unable to even pay interest on the debt.[100] The state narrowly avoided bankruptcy by negotiating the transfer of the public works to to the state's creditors in exchange for a 50% reduction in the state's debt.[101][n 7] The internal improvements began under Jennings paid off as the state began to experience rapid population growth that slowly remedied the state's funding problems. The improvements led to a fourfold increase in land value, and an even larger increase in farm produce.[102]

During the 1840s, Indiana completed the process of removing the Native American tribes. The Potawatomi were relocated to Kansas in 1838. Those who did not leave voluntarily were forced to travel to Kansas in what came to be called the Potawatomi Trail of Death, leaving only the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians in the Indiana area.[103] The majority of the Miami tribe was removed in 1846, although many members of the tribe were permitted to remain in the state on lands they held privately under the terms of the 1818 Treaty of St. Mary's.[104] The other tribes were convinced to leave the state voluntarily. The Shawnee migrated westward to settle in Missouri, and the Lenape migrated into Canada. The other minor tribes in the state, including the Wea, moved westward, mostly to Kansas.

By the 1850s, Indiana had undergone major changes: what was once a frontier with sparse population had become a developing state with several cities. In 1816, Indiana's population was around 65,000, and in less than 50 years, it had increased to more than one million inhabitants.[105]

Because of the rapidly changing state, the constitution on 1816 began to be criticized.[106][n 8] Opponents claimed the constitution had to many appointed positions, the terms established were inadequate, and some of the clauses were too easily manipulated by the political parties that did not exist when then constitution was wrote.[107] The first constitution had not been put to a vote by the general public, and following the great population growth in the state, it was seen as inadequate. A constitutional convention was called in January 1851 to create a new one. The new constitution was approved by the convention on February 10, 1851, and submitted for a vote to the electorate that year. It was approved and has since been the official constitution.[108]

Higher education

For a list of institutions, see Category:Universities and colleges in Indiana.

The earliest institutions of education in Indiana were missions, established by French Jesuit priests to convert local Native American nations. The Jefferson Academy was founded in 1801 as a public university for the Indiana Territory, and was reincorporated as Vincennes University in 1806, the first in the state.[109]

Indiana was the first state to have state funded public schools. The 1816 constitution required that Indiana's state legislature create a "general system of education, ascending in a regular gradation, from township schools to a state university, wherein tuition shall be gratis, and equally open to all". It took some time for the legislature to fulfill its promise, partly because of a debate regarding whether the Territory of Indiana's public university should be adopted as the State of Indiana's public university, or whether a new public university should be founded in Bloomington to replace the territorial university.[110] The state government chartered Indiana University in 1820 as the State Seminary. Construction began in 1822; the first professor was hired in 1823; classes were offered in 1824. The 1820s also saw the start of free public township schools. During the administration of William Hendricks a plot of ground was set aside in each township for the construction of a schoolhouse.[111]

Other state colleges were established as the state grew. Some were private institutions, such as Wabash College, established in 1832.[112] The University of Notre Dame received a charter from the Indiana General Assembly in 1844, but was based on the campus of a Potawatomi mission established a decade earlier.[113] Other schools were publicly owned, such as Indiana State University, established in Terre Haute in 1865 as a state normal school. Purdue University was founded in 1869 as a school of science and agriculture. Ball State University was founded as a normal school in the early 1900s and gifted to the state in 1918.[114]

Transportation

In the early 19th century, most transportation of goods in Indiana was done by river. Most of the state's estuaries drained into the Ohio River, ultimately meeting up with the Mississippi River, where goods were transported and sold in New Orleans.[115][116]

The first road in the region was called Buffalo Trace, an old bison trail that ran from the Falls of the Ohio to Vincennes.[117] After the capitol was relocated to Corydon, several local roads were created to connect the new capitol to the Ohio River at Mauckport and to New Albany. The first major road in the state was the National Road, a project funded by the federal government. The road entered Indiana in 1829 connecting Richmond, Indianapolis, and Terre Haute with the eastern states and eventually Illinois and Missouri in the west.[118] The state adopted the advanced methods used to build the national road on a statewide basis and began to build a new road network that was usable year-round. In the 1830s a North-South road was built, the Michigan Road, connected Michigan and Kentucky and passed through Indianapolis in the middle.[119] These two new roads were roughly perpendicular within the state and served as the foundation for a road system to encompass all of Indiana.

In 1832, the state began construction on the Wabash and Erie Canal. The canal was started at Lake Erie, passed through Fort Wayne, and connected to the Wabash River. This new canal made water transport possible from New Orleans to Lake Erie on a internal route rather than sailing around the whole of the Eastern United States and entering through Canada. Other canal projects were started, but all were abandoned before completion due to the states foundering credit after the devaluation of the bonds.[120]

The first railroad in Indiana was built in Shelbyville in the late 1830s. The first major line was completed in 1847, connecting Madison with Indianapolis. By the 1850s, the railroad began to become popular in Indiana. The railroad brought major changes to Indiana and enhanced the states economic growth.[96] Although Indiana's natural waterways connected it to the South via cities such as St. Louis and New Orleans, the new rail lines ran East-West, and connected Indiana with the economies of the northern states.[121] As late as mid-1859, no rail line yet bridged the Ohio or Mississippi rivers.[122] Because of an increased demand on the states resources and the embargo against the Confederacy, the rail system was mostly completed by the end of the American Civil War.

Civil War

Indiana, a free state and boyhood home of Abraham Lincoln, remained a member of the Union during the American Civil War. Indiana regiments were involved in all the major engagements of the war and almost all of the engagements in the western theater. Hoosiers were present in both the first and last battles of the war. During the course of the war Indiana provided 126 infantry regiments, 26 batteries of artillery, and 13 regiments of cavalry to the cause of the Union.[123]

In the initial call to arms issued in 1861, Indiana was assigned a quota of 7,500 men—a tenth of the total amount called, to join the Union Army in putting down the rebellion.[124] So many volunteered in the first call that thousands had to be turned away. Before the war ended Indiana contributed 208,367 men to fight and serve in the war.[125] Funk 1967, p. 3–4</ref> Casualties were over 35% among these men. 24,416 lost their lives in the conflict and over 50,000 more were wounded.[125]

At the outbreak of the war, Indiana was run by a Democratic and southern sympathetic majority in the State Legislature. It was by the actions of Governor Oliver Morton, who illegally borrowed millions of dollars to finance the army, that Indiana was able to contribute so greatly to the war effort.[126] Morton suppressed the state legislature with the help of the Republican minority to prevent it from assembling during 1861 and 1862. This prevented any chance the Democrats had in interfering with the war effort or attempting to secede from the Union.[127]

Morgan's Raid

The only Civil War battle fought in Indiana occurred during Morgan's Raid. On the morning of July 9, 1863, Morgan attempted to cross the Ohio River into Indiana with his force of 2,400 cavalry. After his crossing was briefly contested he marched north to Corydon where he engaged the Harrison County branch of the Indiana Legion in the short Battle of Corydon before the militia withdrew into the town. Morgan took command of the heights south of Corydon and shot two shells from his batteries into the town, which promptly surrendered. The battle left fifteen dead, forty wounded, and 355 captured.[128]

Morgan's main body of troopers raided and camped at New Salisbury that night while detachments raided and sacked Crandall, Palmyra and the surrounding countryside. Morgan resumed his northward march, destroying much of the town of Salem. Fear gripped the capitol, and the militia began to form there to contest Morgan's advance. After Salem, however, Morgan turned east, raiding and skirmishing along this path and leaving Indiana through West Harrison on July 13, thus ending Indiana's only military confrontation in the war.[128]

Aftermath

The Civil War had a big impact on the development of Indiana. Prior to the Civil war, the population was generally in the south of the state where easy access to the Ohio River provided a convenient means to export products and agriculture to New Orleans to be sold. The war closed the Mississippi to traffic for nearly four years and led to continued disruption to it for years afterwards, forcing Indiana to find other means to export its produce. This led to a population shift to the north where the state came to rely more on the great lakes and the railroad for exports[129][130]

Before the war, New Albany was the largest city in the state mainly because of its river contacts with the South.[131] Over half of Hoosiers with over $100,000 lived in New Albany.[132] During the war, the trade with the South came to a halt, and after the war much of Indiana saw New Albany as too friendly to the South. The city never regained its stature, remaining a city of 40,000 with only its early-Victorian Mansion-Row buildings to remind itself of its boom period.[133]

Indiana's Senators Schuyler Colfax and Oliver Morton (who was elected senator after his final term as governor) were among the supporters of radical punishment on the south during the debate on Reconstruction. They had not supported Lincoln and President Andrew Johnson's plan for reintegrating the southern states. Both senators voted in favor of Johnson's impeachment, Morton was especially disappointed when they failed to remove him.[134][135] Senator Colfax was elected Vice President of the United States in 1868 and served under President Ulysses S. Grant.

Post-War era

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 1,680,637 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,978,301 | 17.7% | |

| 1890 | 2,192,404 | 10.8% | |

| 1900 | 2,516,462 | 14.8% | |

| 1910 | 2,700,876 | 7.3% | |

| 1920 | 2,930,390 | 8.5% | |

| 1930 | 3,238,503 | 10.5% | |

| [95] | |||

Indiana changed dramatically after the Civil War. Ohio River ports had been stifled by an embargo to the Confederate South, and never fully recovered leading the south into an economic decline.[136] By contrast, northern Indiana experienced an economic boom when natural gas was discovered in the 1880s, which directly contributed to the rapid growth of cities such as Gas City, Hartford City, and Muncie where a glass industry developed to utilize the cheap fuel.[137] The boom lasted until the early 1900s, when the gas supplies ran low. This began northern Indiana's industrialization and ultimately led to Indiana becoming part of the Rust Belt.[138][139]

In 1876, chemist Eli Lilly, an Union colonel during the Civil War, founded Eli Lilly and Company, a pharmaceutical company. His initial innovation of gelatin-coating for pills led to a rapid growth of the company that eventually grew into Indiana's largest corporation, and one of the largest corporations in the world.[140][n 9] Over the years, the corporation saw the development of many widely used drugs, including insulin, and becoming the first company to mass produce penicillin. The company's many advances made Indiana the leading state in production and development of medicines.[141]

Charles Conn returned to Elkhart after the Civil War and established C.G. Conn Ltd., a manufacturer of musical instruments.[142] The company's innovation in band instruments made Elkhart an important center of the music world, and it became a base of Elkhart's economy for decades. Nearby South Bend experienced continued growth following the Civil War, and became a large manufacturing city. Gary was founded in 1906 by the United States Steel Corporation as the home for its new plant.[143]

During the postwar era Indiana became a critical swing state that often decided which party controlled the Presidency. The national parties each vied for Hoosier support and a Hoosier was included in all but one election between 1880 and 1924.[144][145] Indiana Representative William Hayden English was nominated for Vice-President and ran with Winfield Scott Hancock in the 1880 election. Their ticket lost to James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur.[146] In 1884, former Indiana Governor Thomas A. Hendricks was elected Vice-President of the United States. He served until his death on November 25, 1885 under President Grover Cleveland.[147]

In 1888, Indiana Senator Benjamin Harrison, grandson of territorial Governor William Henry Harrison, was elected President of the United States and served one term. Fort Benjamin Harrison was named in his honor. He remains the only U.S. President from Indiana. Indiana Senator Charles W. Fairbanks was elected Vice-President in 1904, serving under President Theodore Roosevelt until 1913.[148] Fairbanks made another run for Vice-President with Charles Evans Hughes in 1912, but their ticket lost to Woodrow Wilson and Indiana Governor Thomas R. Marshall, who served as Vice-President from 1913 until 1921.[149]

The administration of Governor James D. Williams proposed the construction of the fourth state capitol building in 1878. The third state capitol building was razed and the new one was constructed on the same site. Two million dollars was appropriated for construction and the new building and it was completed in 1888. The building was still in use in 2008.[150]

The Panic of 1893 had a severe negative effect on the Hoosier economy when a number of factories closed and several railroads declared bankruptcy. The Pullman Strike of 1894 hurt the Chicago area and coalminers in southern Indiana declared a strike. Hard times were not limited to industry; farmers also felt a financial pinch from falling prices. The economy began to recover when war broke out in Europe creating a higher demand for American goods.[151]

Post-war Indiana saw several major criminal events. A group of brothers from Seymour, who had served in the Civil War, formed the Reno Gang, the first outlaw gang in the United States.[152] The Reno Gang, named for the brothers, terrorized Indiana and the Midwest for several years. They were responsible for the first train robbery in the United States which occurred near Seymour on October 6, 1866. Their actions inspired a host of other outlaw gangs who copied their work, beginning several decades of high-profile train robberies. Pursued by detectives from Pinkerton Detective Agency, most of the gang was captured in 1868 and lynched by vigilantes.[152] Other notorious Hoosiers also flourished in the post-war years, including Belle Gunness, an infamous "black widow" serial killer. She is believed to have killed more than twenty people, most of them men, between 1881 and her suspected murder in 1908.[153]

Twentieth century

Although industry was rapidly expanding throughout the northern part of the state, Indiana remained largely rural at the turn of the century with growing population of 2.5 million. Like much of the rest of the American Midwest, Indiana's exports and job providers remained largely agricultural until after World War I. Indiana's developing industry, backed by an educated population, low taxes, easy access to transportation, and business friendly government, led Indiana to grow into one of the leading manufacturing states by the mid-1920s.[154]

In 1907, during the administration of Governor Frank Hanly, Indiana became the first state in the Union to adopt eugenics legislation, but was until ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of Indiana in 1921.[155] A revised eugenics law was passed in 1927, and it remained in effect until 1974.[156] Hanley was also a spokesman in the temperance movement. Prohibition took effect in 1920 and northern Indiana saw some involvement with Al Capone and others in the underground bootlegging. Prohibition remained in effect until 1933.[157]

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway complex was built in 1909, inaugurating a new era in history. The automobile was a new invention and Indianapolis rivaled Detroit in auto manufacturing for several years. The speedway offered a venue for auto companies to show off their products. Europeans and American companies competed to build the fastest automobile in hopes of winning at the track. The Indianapolis 500 quickly became the standard in auto racing.[158]

World War I

Although the majority of Hoosiers supported the Entente Powers in the early years of World War I, a significant number of German-American and Irish-Americans supported neutrality or the Central Powers. Influential Hoosiers who opposed involvement in the war included Eugene V. Debs, Senator John W. Kern, and even Vice President Thomas R. Marshall.[159] Supporters of the Alliance and military preparedness included James Whitcomb Riley and George Ade. Most of the opposition dissipated when the United States officially declared war, but some teachers lost their jobs on suspicion of disloyalty,[160] and public schools could no longer teach in German.[161][n 10]

The Indiana National Guard was federalized during the War, and many units sent to Europe. To replace the missing Guard, Governor James P. Goodrich authorized a new state militia to be formed from men ineligible for the draft, mostly because of their age. The militia was called out several times to quell riots and disturbances in 1918 and 1919. Indiana provided 130,670 troops during the war; a majority of them were drafted. Over 3,000 of these died, many from influenza and pneumonia.[162] To honor the Hoosier veterans of the war the state began construction of the Indiana World War Memorial.[163] Hoosier soldiers were involved in operations on the German and Italian fronts. Major Samuel Woodfill, a native of Jefferson County, became the most decorated soldier of any nation to fight in the war, receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor, the Croix de Guerre and admited to the Légion d'honneur by France, the Meriot di Guerra Cross from Italy, and the Cross of Prince Danilo from Montenegro, among numerous others.[164]

Twenties and the Great Depression

The war-time economy provided a boom to Indiana's industry and agriculture, which led to more urbanization throughout the 1920s. By 1925 Indiana had passed a great milestone: more workers were employed in industry than in agriculture. Indiana's greatest industries were steel production, iron, automobiles, and railroad cars.[165]

Scandal erupted across the state in 1925 when it was discovered that over half the seats in the General Assembly were controlled by the Klu Klux Klan. During the 1925 General Assembly session Grand Dragon D. C. Stephenson boasted "I am the law in Indiana." Stephenson was convicted for the murder of Madge Oberholtzer that year and sentenced to life in prison. After Governor Edward Jackson, who Stephenson helped elect, refused to pardon him, Stephenson began to name many of his co-conspirators leading to a string of arrests and indictments against leading Hoosiers including the governor, mayor of Indianapolis, the attorney general, and many others. The crackdown effectively rendered the Klan powerless.[166]

John Dillinger, a native of Indianapolis, began his streak of bank robberies in Indiana and the Midwest during the 1920s. He was captured in 1924 and served a prison sentence in the Indiana State Prison until he was paroled in 1933. Returning to crime, he was returned to prison the same year, but escaped with the help of his gang. His gang was responsible for the theft of over $300,000 and multiple murders. He was eventually killed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation on July 22, 1934 in Chicago.[167]

During the 1930s, Indiana, like the rest of the nation, became caught up in the Great Depression. The economic downturn had a wide-ranging negative impact on Indiana. Much of the movement toward urbanization in the 1920s was lost. The situation was aggravated by the Dust Bowl which caused an influx of immigrants from the west. The administration of Governor Paul V. McNutt struggled to build from scratch a state funded welfare system to help the overwhelmed private charities. During his administration, spending and taxes were both cut drastically in response to the depression and the state government was completely reorganized. McNutt also ended prohibition in the state and enacted the state's first income tax. On several occasions, he declared martial law to put an end to worker strikes.[168]

During the Great Depression, unemployment exceeded 25% statewide. Southern Indiana was particularly hard hit where unemployment topped 50% during the worst years. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) began its operations in Indiana in July 1935. By October of that year, 74,708 Hoosiers were employed by the agency. In 1940, there were still 64,700 working for agency. The majority of these workers were employed to improve the state's roads, bridges, flood control projects, water treatment plants, some indexed libraries, and even create murals for post offices—every community had a project to work on.[165]

During the 1930s many of Indiana's prominent businesses collapsed, several railroads went bankrupt, and numerous banks folded.[169][170] Manufacturing came to an abrupt halt or was severely cut back due the dwindling demand for products. The depression continued to negatively affect Indiana until World War II, and the effects continued to be felt for many years thereafter.

World War II

The regional economy began to recover going into World War II. Although the WPA continued to employ many Hoosiers, unemployment steadily declined as the depression gave way to the war-time economy.

Indiana participated in the Total War mobilization of the nations economy and resources. Domestically, the state produced munitions in an army plant near Sellersburg. The P-47 fighter-plane was manufactured in Evansville at Republic Aviation.[171] The steel produced in northern Indiana was used in tanks, battleships, and submarines. Other war related materials were produced throughout the state. Indiana's military bases were activated, with areas such as Camp Atterbury reaching historical peaks in activity. An Air Force base was constructed near Seymour, Indiana and was the location of the Freeman Field Mutiny. The mutiny led to the racial integration of the United States military.[172]

The population was generally supportive of the war efforts and many men enlisted in the army and navy voluntarily. The state contributed many young men to fight abroad, nearly 400,000 Hoosiers enlisted or were drafted into the war.[173] More than 11,783 Hoosiers died in the conflict and another 17,000 were wounded. Hoosiers served in all the major theaters of the war.[174][175] Their sacrifice was honored by additions to the World War Memorial in Indianapolis, which was not finished until 1965.[176]

Modern Indiana

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 3,427,796 | — | |

| 1950 | 3,934,224 | 14.8% | |

| 1960 | 4,662,498 | 18.5% | |

| 1970 | 5,193,669 | 11.4% | |

| 1980 | 5,490,224 | 5.7% | |

| 1990 | 5,544,159 | 1.0% | |

| 2000 | 6,080,485 | 9.7% | |

| 2007 (est.) | 6,345,289 | [95] |

The end of World War II saw Indiana returned to the pre-depression levels of production. Industry again became the major employer, a trend that accelerated into the 1960s. The urbanization during the 1950s and 1960s years led to a large growth in the state's urban centers with towns and cities like Clarksville dramatically increasing in population. The auto, steel, and pharmaceutical industries topped Indiana's major businesses. Indiana's population continued to grow during the years after the war, passing five million by the 1970 census.[177] In the 1960s, there were several significant developments in the state. During the administration of Matthew E. Welsh the state adopted its first sales tax of two percent. The new sales taxed dramatically increased revenues to the state and spawned a host of state projects. Welsh also worked with the General Assembly to pass the Indiana Civil Rights Bill.[178]

Beginning in 1970 a series of amendments to the state constitution was proposed, several were adopted and the the Indiana Court of Appeals was created and the method of selecting justices on the courts was altered.[179][n 11] Term limits were adjusted for the Governor, allowing him to serve consecutive terms. The 1973 oil crisis created a recession that hurt the automotive industry in Indiana. Companies like Delco Electronics and Delphi began a long series of downsizing that contributed to high unemployment rates in manufacturing in Anderson, Muncie, and Kokomo. The trend continued until the 1980s when the national and state economy began to recover.[180]

In 1988, Senator Dan Quayle was elected Vice-President under George H. W. Bush. He was the 5th Vice-President from Indiana, and served one term. Quayle was the third U.S. Vice-President whose hometown was on Indiana State Road 9, and the highway gained the nickname "Highway of Vice Presidents."

Central Indiana was struck by a major flood in 2008 leading to widespread damage and the evacuations of hundreds of thousands of residents, making it the costliest disaster in the history of the state.

See also

- History of Indianapolis

- Indiana Territory

- Indiana Historical Society

- Indiana Register of Historic Sites and Structures

- List of battles fought in Indiana

- List of Governors of Indiana

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Indiana

- List of Registered Historic Places in Indiana

- List of State Historic Sites in Indiana

Notes

- ^ At the negotiations at Greenville, Chief Little Turtle of the Miami Tribe asserted a Miami claim to half of Ohio, all of Indiana, and eastern parts of Illinois, including present day Chicago.

- ^ Photo available at Historical Marker Database. Retrieved on May 13, 2008.

- ^ The father of François-Marie Picoté de Belestre

- ^ According to some sources Thomas Posey refused to live in Corydon because of his ongoing quarrel with Dennis Pennington. See: Gresham, p. 22

- ^ The origin of the word Hoosier is unknown

- ^ Map on page Nevins, p. 209 shows that as of 1859, no Railroad crossed the Mississippi or Ohio Rivers.