Ancient Greek potters

The potters ( ancient Greek κεραμεύς kerameus ) of Greek antiquity exercised one of the oldest professions of mankind and managed to greatly enrich it in terms of technology and artistry .

Working method

Greek potters of antiquity only worked by hand, on the rotating pottery wheel , and with the help of male and female molds and models . Specializing in certain product groups is very likely. The work of the potter encompassed much more than the actual production of vessels and other products from clay. The work began with the clay mining, continued with the clay preparation and led through the fire to the sale of the products. Also the painting , which was common for some of the ceramics , especially from the Sub-Mycenaean period towards the end of the 11th century BC. Until about the end of the Classical period towards the end of the 4th century BC. Was mostly part of the pottery.

The first Greek potters are likely to have been wandering potters. In the course of the archaic period at the latest , however, they settled down and pottery quarters emerged in many places, which mostly also took up other professions that had similar working methods or material requirements, such as ore caster or tanner.

The working techniques of the potters had to be reconstructed by researchers and are still not completely clear in all details. The pioneers of this direction of experimental archeology which owned Heidelberger Classical archaeologist Roland Hampe together with the ceramist Adam Winter , being based ethnoarchäologischer studies in Mediterranean beheld surviving techniques before final downfall.

Archaic and classic

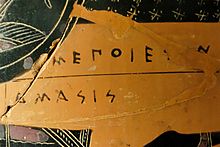

In addition to the vessels themselves, antique potters have been used since around the 7th century BC. When the first signed vases were made on Euboea . The first known signature comes from a crater made by the potter Aristonothos . The signature mostly had the addition epoíesen ἐποίησεν ‚hat made ' after the name , at the beginning also in the form m'epoíesen , made me . A little later the first signatures followed in West Greece, then more and more in East Greece. In the early 6th century BC A number of Boeotian figure vases were signed. It is noticeable that the center of painted ceramics of the 7th and 6th centuries, Corinth , has only a few pottery signatures to show. Thericles is known from written records for his outstanding works, none of which have survived. During the 6th century BC Chr. The predominance of skill and economic success changed to Athens. In proportion to their success, the Attic potters of the black-figure style also became more willing to sign . Important potters included Sophilus , Nearchus , Exekias , Amasis and Andokides . Nikosthenes held a special position , who had run a workshop with his successor Pamphaios that can be traced for at least two generations. Especially under Nikosthenes, she showed a particularly great willingness to experiment, which had to do with a production geared towards export - especially to Etruria . For example, Nikosthenes adapted Etruscan forms to be even more attractive for the local market, and in doing so created the Nikosthenic amphora, which is only intended for export . There were also many signing potters among the minor masters ; these signatures were not infrequently used as part of the decoration.

|

|

|

|

Nicosthenic amphora (left), Louvre, Paris F 111, and Etruscan Bucchero model (right), Villa Giulia, Rome

|

||

With the change from the black-figure to the red-figure style in the last third of the 6th century BC. A somewhat longer lasting structural change in the workshops also seemed to have reached its climax. For a long time, potters and vase painters were likely to be identical people, but individual work steps were increasingly taken over by specialists or, at least in phases, individual work was carried out in series production by specific employees. Unfortunately, as in almost all areas, there is no written record here and archeology is solely dependent on stylistic observations. Probably by the change from the 6th to the 5th century at the latest, it was normal for a potter to employ several vase painters in his workshop. It is also possible that the vases were painted by younger employees of the company. The other way around, it was apparently just as possible for vase painters to work for different potters. The vase painter Oltos began in the workshop of Nikosthenes and the Pamphaios and then worked for the potters Hischylos , Tleson , Chelis , Kachrylion and Euxitheos . There are also very close collaborations between potters and vase painters, such as Duris and Python , Hieron and Makron or Brygos and Brygos painters . Another possibility is the collaboration of several potters, since the construction of a kiln and the fire was a complicated, risky affair. In addition, it is very likely that part of the training of young ceramists was not only vase painting, but also the actual pottery. Since it can be assumed that more than just representative painted pieces were offered, the production of the smaller pieces, the pieces with a varnish coating or the serially produced pieces painted with less care was left to apprentices or unskilled workers. What, however, in the course of the 6th century BC. A specialization of the workshops in pottery for bowls and similar open vase forms and closed vessels was ascertainable. A further specialization of the latter potters in specialists for lekyths , pitchers or amphorae is quite possible.

The potter was generally the owner of the workshop and thus the manager of the business. In contrast to the perception today, in which the vase painting is the most obvious detail, at least in the painted vases, in antiquity the appreciation was more for the creator of the vessels. In several cases there are careers in which vase painters later became respected potters, the " pioneers " Euphronios and Euthymides are particularly well known . How this career took place, whether the activity as a vase painter was part of the training and later a parental workshop was taken over, whether the workshop was acquired or whether it was different, must remain speculation.

Despite a number of preserved potters' signatures, signing remained the exception; with the few potters, of whom there are a particularly large number of signatures, there were mostly special reasons. With Nikosthenes, for example, the visibility for export, with the creators of plastic vessels, Charinos and Sotades , probably out of pride in their craft. Another form of craftsmanship's pride was the representation of processes in the pottery, which kept occurring. Various vase production processes were also shown on the Pinakes by Penteskouphia . About 100 potters are known for their signatures for attic. In comparison, there are only about 40 vase painters who have signed their works. This also speaks for the importance of the potters compared to the vase painters. In the 5th century BC The signatures became noticeably fewer in the 4th century BC. They are very rare now.

In contrast to the vase paintings by anonymous vase painters, the works of anonymous potters or even unsigned works by well-known potters have been relatively little studied to this day. Pioneering work was done by Hansjörg Bloesch , who, with his work, forms of Attic bowls from Exekias to the end of the Strict Style, laid the foundations for the attribution of vases to potters. As with the vase painters, who, if they are not known by name, have often received an emergency name after a well-known potter for whom they worked, potters today are often given an emergency name that is based on a vase painter with whom they worked more often . So named Adrienne Lezzi-Faulty the M-pottery after the Mannheim Painter , the S Potter after Shuvalov Painter .

For southern Italy - Magna Graecia - it can be assumed even more than in Attica that the work in the pottery workshops was similar to a manufacture. In contrast to Athens, where many smaller individual craftsmen were responsible for the pottery industry, there were probably mostly larger companies in which many craftsmen worked together.

Hellenism and Roman Empire

|

|

|

|

One- handled head haros of the potter Likinnios with signature mark ; 1st century BC Chr .; J. Paul Getty Museum , Malibu 83.AE.40

|

||

With the advent of Hellenism , much of the foundations of pottery changed. Instead of painted vases, ceramic decorated with a relief, which was made in molds, was now fashionable. This also changed the structure and workflow in the workshops. Signatures change over time from a personal signature for a work to a brand name, to a factory mark , whereby the owner of the workshop stands for the entire product range. A particularly well-known representative of this was the Athenian Ariston , in whose pottery both relief bowls and clay lamps were made from the matrix.

The focus of production shifted, although Athens continued to be a ceramic production center, at least regionally. But potteries from Pergamon, for example, had taken over the Mediterranean-wide sales market with their relief ceramics (" Megarian cups "). Obviously, these newly created states, with their fresh dynamism, coped better with the changed market conditions than the old production centers.

In Roman times the number of signatures increased significantly and a very large number of names are known. The owners of the pottery signed in the genitive, the potters, often Greek slaves, in the nominative.

Social position

As is the case with most crafts, there are almost no written reports from ancient authors on the potters. The little information is largely limited to ancient Athens . At least at times, the economic conditions for potters were very good here. The Attic comedy suggests that there was a certain class ranking among the various specialists in individual ceramic products, with the lowest tier being occupied by the lamp potters.

While Homer Töpfer still calls Demiourgoi , “ those who work for the common good”, the Attic sources from old and middle comedy allow a rather disdainful look at the banahmi (literally: “stove stool”). However, these traditions are in most cases determined by wealthy aristocrats, so that there was obviously a discrepancy in self-image and the perception by the elite, if a changed view of the commoners did not lead to the different assessments. Was the vase painter full citizens of Athens, so he was as Demiourgos the tax bracket of Theten to, in the rare cases of both existing, modest land ownership tax bracket of zeugitae . A high proportion of metics is also very likely . The increasing role of the money economy during the 6th century BC BC and the economic successes of Attic potters, especially towards the end of it, led, if not to growing social recognition, then at least to growing self-confidence of the potters and vase painters. This was reflected in a series of consecration gifts donated by potters to the Athens Acropolis , including the potter and vase painter Euphronios, who calls himself kerameus ("potter") in the inscription that has survived . Vase painters also donated particularly finely decorated ceramic vessels to the Acropolis.

Towards the end of the 6th century BC The economic situation of the potters seemed to have been particularly good and potters showed a high level of self-confidence. In the course of the reforms of Kleisthenes , processes that had been going on for a while were fueled even further. The pottery district of Athens, the Kerameikos named after the potters , became a field of experimentation for technically skilled but also commercially inclined craftsmen. During this early phase of democracy, various artisans apparently achieved a certain level of prosperity so that they could consecrate significant votive offerings to the gods on the Acropolis . Above all, representatives of the pioneer group showed themselves on vase pictures or in annotated inscriptions. Euthymides, Euphronios and Smikros will be shown at the symposium , there are also pictures with inscriptions showing vase painters as athletes in the palaestra . A picture by the antiphon painter also shows a vase painter who reveals himself to be a citizen through a walking stick leaning against the wall and an athlete through Strigilis and Aryballos on the wall. To what extent this was a dream in aristocratic spheres or corresponded to reality is unclear.

The potters Kittos and Bakchios were unusual in their prestige . The brothers, sons of the no less well-known potter Bakchios , had made Panathenaic price amphoras in Athens and later emigrated to Ephesus , where they had become citizens because of their skills. The grave stele has been handed down from the father, on which he is praised for his craft skills and the victories in craft competitions. Nothing is known about these competitions. A great deal of mobility can also be seen in vase painters in particular, but also in some cases in potters. Especially in the course of military, social or economic problems, ceramists repeatedly left their ancestral home and settled elsewhere in the Greek world, where they introduced their local knowledge and skills. Greek ceramists are known in Etruria, Attic craftsmen in Boeotia, Lower Italian ceramists who came from Attica or Eastern Greece, and similar constellations.

Outside Attica, it is even more difficult to assess one's social position than in Athens. In Laconia, for example, the vase painters were probably Periöks or craftsmen who had moved there. The ceramists in Boeotia were apparently somewhat more respected than in Athens. It is also difficult to make assessments for craftsmen from the pre-Homer era, as there are no written evidence and there are hardly any archaeological finds that would allow such conclusions to be drawn. Probably still in Homeric times and, analogously, in earlier times, potters, who were also vase painters at the time, were traveling craftsmen who offered their services in different places. In Athens, as in Corinth, pottery quarters may already have emerged in Geometric times - the Athenian Kerameikos is famous, who also remained a cemetery and thus an important buyer of grave vases up to the classical period. The workplace of the potters and thus the vase painters was thus on the edge or outside of the cities, where the danger of the kilns causing fires was far lower.

Today's view of potters as artists corresponds to modern viewing habits and values. In the 6th and 5th centuries BC However, this concept of the artist did not yet exist; no distinction was made between “high art” and handicrafts . The "artists" were technites . The ancient vase painters therefore saw themselves as artisans who worked under the protection of Athena Ergane . Your current classification as an artisan is therefore the most appropriate.

literature

- Ingeborg Scheibler : Greek pottery art. Manufacture, trade and use of the antique clay pots (= Beck's archaeological library ). CH Beck, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-406-09544-5 .

- Wolfgang Schiering : The Greek clay pots. Shape, purpose and change of form (= Gebr. Mann-Studio-series ). 2nd, significantly changed and expanded edition. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-7861-1325-4 .

- Toby Schreiber: Athenian Vase Construction. A Potter's Analysis. J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu 1999, ISBN 0-89236-465-3 ; ISBN 0-89236-466-1 ( digitized version ).

- Ingeborg Scheibler: potter. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 12/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01482-7 , Sp. 650-652.

- John Boardman : The History of Greek Vases. Potters, Painters and Pictures. Thames & Hudson, London 2001, ISBN 0-500-28593-4 .

- John H. Oakley : The Greek Vase. Art of the storyteller. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 2013, ISBN 978-1-60606-147-3 .

On experimental archeology and ethno-archeology

- Roland Hampe , Adam Winter : With the potters in Crete, Messenia and Cyprus . Zabern, Mainz 1962. Reprint 1976, ISBN 3-8053-0254-1 .

- Roland Hampe, Adam Winter: Among the potters and brick makers in southern Italy, Sicily and Greece . Zabern, Mainz 1965

- Adam Winter: The antique gloss ceramic. Practical experiments (= ceramic research . Volume 3). Zabern, Mainz 1978, ISBN 3-8053-0333-5 .