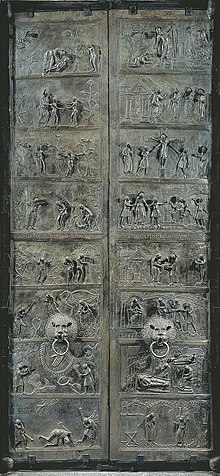

Bernward door

The Bernwardstür is a two-winged bronze door in the west portal of Hildesheim Cathedral, dated around 1015 . Her rich biblical decoration of figures, which juxtaposes scenes from Genesis with the life of Jesus Christ , is considered to be the first picture cycle of German sculpture . After the restoration, the door wings in an anteroom point outwards again and thus presented the porta salutis , the door to salvation , to the arriving person . For reasons of conservation, the gate leaves are only opened on special occasions. The door that takes its name after its client, Bishop Bernward von Hildesheim(983-1022), is considered to be one of the major works of Ottonian art .

Work history

The door, together with the Christ column, is part of Bishop Bernwards’s efforts to give his episcopal city a cultural hegemony through artistic excellence as part of the renewal of the Roman Empire aimed at by the Saxon emperors. A Latin inscription on the central transverse frame, which was still engraved during Bernward's lifetime , shows the year 1015 as the terminus ante quem for the manufacture of the doors:

“AN [NO] DOM [INICE] INC [ARNATIONIS] M XV B [ERNVARDVS] EP [ISCOPVS] DIVE MEM [ORIE] HAS VALVAS FVSILES IN FACIE [M] ANGELICI TE [M] PLI OB MONIM [EN] T [VM ] SVI FEC [IT] SVSPENDI "

"In the year of the Lord 1015, Bishop Bernward - blessed memory - had these cast door leaves hung on the facade of the angel's temple in his memory."

The "angel temple" mentioned in the inscription is identified by some of the researchers with Bernwards Church of the Holy Sepulcher, St. Michael . According to these, the doors were originally there on the southern side aisle (possibly separated into two portals) or in the cloister or in a no longer existing Westwerk hooked and came first in the cathedral when Bishop Godehard his, of Wolf Here written biography ( Vita Godehardi ) According to In 1035 he created a west entrance and had the door of his predecessor Bernward hung here. The excavation findings (building research ) from 2006 now seem to rule out that Saint Michael once had a westwork. For the installation of the door, the south side is more likely to be considered anyway, where remains of the foundations of a vestibule have been excavated next to the western stair tower . The latest research in the history of cults now also shows the “templum angelicum” as a liturgical formula for a dedicated St. Michael’s patronage. Other researchers assumed that the Bernward door was intended for Hildesheim Cathedral from the start, although the westwork with vestibule was not laid out by Bishop Godehard until 1035. They assume that Bernward built a western building here, the appearance of which cannot be clearly reconstructed today. Either Bernward had the previous west choir and the crypt underneath demolished in order to make space for a representative vestibule, in whose portal the Bernward door could be inserted, or he had the west choir and the door in the portal of a chapel, which was at the front of the Apse was added to hang up. However, only a few remains of the foundations speak for the assumption of a Bernwardin western building on the cathedral , which also hardly allows detailed statements about its exact shape. There are no written sources for Bernward's construction work on the cathedral. Such a location of the doors in the west building would have had to be changed again soon anyway, as the cathedral was already extensively rebuilt under Bernward's successors Godehard, Azelin and Hezilo . The radical rebuilding of the western parts in the years 1842–1850 did the rest. Most recently, the westwork was largely rebuilt after severe bomb damage in the Second World War . The underlying, not undisputed plan by Wilhelm Fricke was not based on the presumed state of construction at the time of Bernwards, but on the westwork of Minden Cathedral and the presumed appearance of the Hildesheim western front under Bishop Hezilo (construction period 1054-1061).

The door wings escaped the bombing raid on Hildesheim on March 22, 1945 only because they had been removed from the furnishings almost three years earlier on the initiative of the cathedral chapter, together with numerous other works of art. At that time, the heavy door leaves, lying on their long sides and clamped in a stable wooden frame, had to be pulled by two horse and carts on a trolley to the so-called Kehrwiederwall in the southeast of the old town, where they survived the war in an underground passage. In the course of the extensive renovation of the cathedral from 2010 to 2014, the Bernward door was repositioned, back from the western outer wall to its original place in the eastern end wall of the western paradise. Since then, the two door leaves have been self-supporting again, so turn by themselves using the historic bronze pivot.

Manufacturing and technical characteristics

The door leaves were each cast from one piece. In view of the dimensions (left 472.0 × 125.0 cm, right 472.0 × 114.5 cm, maximum thickness approx. 3.5–4.5 cm) and the enormous weight (approx. 1.85 t each) of the Door leaf, this was a great technical achievement for those times. The raw material used for casting was gunmetal , which consists primarily of copper (over 80%) and approximately equal parts of lead , tin and zinc . However, the previous material analyzes could not clarify from which ore deposit the metals used originate; the hut on Rammelsberg near Goslar , which was already occupied at the time , is out of the question.

Like its predecessors in Aachen and Mainz, the Bernward door was manufactured using the lost wax process, which placed the highest demands on the workers in the foundry workshop, as the mold could only be used once. The individual scenes of the picture cycle were scraped out of massive wax or tallow panels by the modellers and only then put together, supported by an iron frame ; this probably also caused the slight irregularities in the banding that divides the individual representations. The door pullers in the form of grumpy lion heads with a grace ring were not soldered on afterwards , but were already present on the wax mold. Technical analyzes have shown that the clay mold was filled with bronze standing on the long side so that the liquid metal could spread out well. Additional castings or overlay on the doors show that cracks had formed in the metal when it cooled down. The cold raw casting of the door leaf was probably still quite coarse, covered with metal ridges at the point of the drainage and exhaust air ducts in the clay mold and still had to be reworked to a large extent by chasing .

Style and composition

Overall concept

The Bernward door has the shape of an antique frame panel door; In contrast to the Roman originals, this design in Hildesheim is not due to the design, but rather a quote reminding of the ancient tradition. In addition, due to the narrow width and the flat relief, the effect of the frames is greatly reduced in favor of the figure scenes, so that they look more like the picture strips of a contemporary manuscript - such as in the Gospels of Echternach .

Composition of the scenes

The composition of the individual scenes is as simple as it is effective. In contrast to the scenic representations of Carolingian art , the artists dispensed with richly designed backgrounds that simulate spatiality . The scenarios, consisting of plants (mainly on the left wing) and architecture (mainly on the right wing), are executed in bas-relief and limited to a minimum. They are only found where they are necessary to understand the presentation or for compositional reasons. Instead, large open spaces bring out the outlines of the few figures that move in them particularly well - Alexander von Reitzenstein therefore called the empty pictorial spaces the “field of activity of corresponding gestures”. Through their movements and expressive gestures, each person is related to another, hardly a single figure would be conceivable as a single piece without its counterpart, otherwise it would lose its meaning.

characters

As is usual in medieval art, the figures do not have individual physiognomies , rather they are stylized types that are partially repeated. The disproportionately large, oval faces are characteristic of Ottonian sculpture. Oversized, almond-shaped eyes sit in shallow eye sockets, which are closed on the forehead by a sharp-edged brow arch. The hair consists of parallel strands and is combed to the middle part. Nonetheless, the facial expressions are sometimes very expressive and work well together with the gestures. Particularly noticeable in this context is the figure of Cain from the fratricide scene, who looks up to God's hand in the sky with fearful, wide eyes and holds his cloak in front of his body to protect himself.

A special feature of the figures on the Bernward door is their relief style: the figures do not emerge evenly from the surface, but rather 'lean' out of it, so that in the flat side view they almost give the impression of a “rose trellis with nodding heads”. A particularly significant example of this is the figure of Mary with the baby Jesus in the scene of the Adoration of the Magi: while the lower body is still worked as a bas-relief, the upper body and Christ protrude further and further upwards; Finally, the shoulder and head of Maria are three-dimensional. This unusual relief style is definitely intentional in terms of design and cannot be attributed to reasons of casting technique.

Master question

In contrast to the market portal of Mainz Cathedral , for example, there is no master's name for the Hildesheim Bernward door. This has led to the fact that the older research tried to determine a changing number of different masters on the basis of stylistic analyzes of the individual image fields. However, Rainer Kahsnitz has meanwhile questioned these ascriptions, since the differences in the processing of the reliefs are so minor that they are more due to technical necessities than to different artistic conceptions. It is possible that only a single master was involved in the manufacture of the Bernward door, who had a small group of journeymen and assistants under him.

iconography

The Bernwardstür contains the oldest monumental cycle of pictures in German sculpture. It follows a salvation history and typological image program . The 16 fields show scenes from the Old Testament (on the left door) and the New Testament (on the right door). On the left, descending from above, the story of the increasing distance of humans from God is shown ( creation , the fall of man , fratricide ), on the right, ascending from below, the redemptive work of Christ, from the proclamation and birth through the passion story to the resurrection . The narrative method of depicting several successive parts of a Bible story in one and the same picture field corresponds to the practice of contemporary book illumination . As a result, Adam appears twice in the scene of his awakening by the Creator, and the apple even five times in the scene of the fall.

The depictions of the right wing of the door, where Jesus' birth and childhood are immediately followed by passion and resurrection, are thematically supplemented by the picture narration of his public life on the Christ column, which, also donated by Bernward, was in the east choir of St. Michael until the 18th century was standing.

In addition to the chronological reading, the opposing image fields can also be placed in a typological relationship ( concordantia veteris et novi testamenti ). The interpretations are mainly based on the theological writings of the Church Fathers , especially Augustine :

| Left wing (Genesis) | Right Wing (Life of Jesus Christ) | Typological context |

|---|---|---|

| God brings Adam to life, Adam pays homage (?) To God the Father | Noli me tangere / Ascension of Christ | The awakening Adam foreshadows the resurrected Christ. |

| Bringing Adam and Eve together | Women at the grave | Adam and Eve as a couple correspond to Christ and the women at the grave, who are figuratively interpreted as "Brides of Christ". |

| Fall of Man | Crucifixion of Christ | The fall of man is the starting point of the original sin , which is blotted out through Christ's sacrificial death on the cross ( 1 Cor 15:22 EU ). |

| Interrogation and judgment of Adam and Eve | Christ before Pilate / Herod | While the condemnation of the first parents heralds the beginning of the godless, sinful and painful world, the condemnation of Christ heralds the imminent redemption through the sacrifice on the cross. Adam and Eve reject their own guilt, Christ takes on the guilt of others. |

| Expulsion from Paradise | Offering in the temple | While Adam and Eve are driven out of the “house of God” because of their sinfulness, Christ opens up the return to Paradise for his followers through the offering in the temple. |

| Earth life Adam and Eve | Adoration of the Magi | Mary as the "new Eve", who outweighs Eve's disobedience in the fall of man through her own obedience to God. |

| Sacrifice of Cain and Abel | Birth of Christ | The lamb that Abel offers to God is a reminder of God's incarnation in Christ and his divine untouchedness. |

| Cain's fratricide | Annunciation | The righteous Abel, who was slain, points to Christ through his blood, which God received at his incarnation. |

Role models and aftermath

For the design of the Hildesheim doors as a frame panel door based on the Roman model and for the choice of material, various suggestions come into question. Outstanding examples of monumental bronze castings were found in the doors of the Aachen Palatine Chapel (around 800) and the market portal of the Mainz Cathedral , the doors of which Archbishop Willigis had made around 1009 by the foundryman Berenger. However, these doors - with the exception of the door puller in the form of lion heads on the Aachen Wolfstür - had no figurative decoration. As his biographer Thangmar reports in Vita Bernwardi , Bishop Bernward lived during his stay in Rome in 1001/02, first in the hostel of the schola Francorum at the Vatican and then in the imperial palace on the Palatine . This gave him the opportunity to study the monumental bronze gate at the entrance to the Constantinian St. Peter's Basilica . He may also have seen the late antique wooden doors of Santa Sabina , dating from around 430, with their cycle of reliefs in which scenes from the Old and New Testaments are typologically contrasted. The late antique doors of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan are also possible models.

As far as the composition of the image fields and the figures in the left door is concerned, Franz Dibelius for the first time noticed clear parallels to depictions in the illumination from the court workshop of Charles the Bald . Some scenes of the Hildesheim doors, e.g. B. the creation of Adam or the earthly life of the first parents are compositionally almost identical to the paintings of the so-called Moutier-Grandval Bible (London, British Library, Ms Add. 10546). Significantly, this late Carolingian manuscript, created around 840, comes from Tours , where Bernward traveled in 1006, only to return to Hildesheim a year later with precious relics for the silver Bernwards crucifix . Close parallels can also be seen with other important magnificent manuscripts of the 9th century. a. to the even older, dating from around 800 Alcuin -Bible ( Bamberg State Library , Msc.Bibl.1) and 877 in the Corbie Abbey created Bible of San Paolo fuori le mura (Rome, Abbazia di San Paolo fuori le mura). That Bernward brought a copy of one of the famous French Bibles with him from his travels has not been proven, but it is probable. The ivory in the cover of the Stammheim Missal , on which Alcuin presented a book to St. Martin as the patron of his monastery, could have come from a Touronic Bible in Bernward's possession. Rudolf Wesenberg also drew frescoes in San Paolo fuori le mura and Alt-St. That were iconographically and stylistically comparable, but only survived in traces . Peter , who Bernward might have seen during his trip to Rome.

A number of other medieval bronze doors were built in the succession of the Bernwardstür, but they have no recognizable connection with Hildesheim. The technique of full casting did not prevail either, because the most important ore doors - such as the bronze door of the Augsburg Cathedral (11th century), the doors of San Zeno Maggiore in Verona (12th / 13th century) and the St. Sophia Cathedral in Veliky Novgorod ( 1152–54) - have a wooden frame on which the bronze reliefs are attached. For the west portal of the Pauluskirche in Worms , the sculptor Lorenz Gedon created a detailed replica of the Bernward door in 1881; In contrast to the original, however, this is made of cast iron , and for reasons of space, the two uppermost image fields are missing on both wings.

Liturgical meaning

According to the Hildesheim Cathedral Ordinarium of 1473, “on Ash Wednesday Vespers in the medium monasterii, the bishop scattered the ashes and expelled the public penitents through the south-western church door. Then he left the cathedral barefoot with the clergy through the large bronze doors, only to return through them after having walked around the building. ”The reference to the rite of expulsion of penitents in Lent appears, based on the model of expulsion of the first parents from paradise already created in the image program itself. "The images of the left wing with the creation of man, the fall of man and the story of Cain and Abel correspond to the breviary reading (Gn 1-5,5) on the Sunday Septuagesima and the following week, with which the pre-Lent begins." Door presumably already at its original location of the instruction of the penitents, who had to stay in the anteroom ( "paradise" ) of the church building during Lent .

Notes and individual references

- ^ Hans Jantzen : Ottonian art . 2nd Edition. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1959, p. 115 .

- ↑ Drescher 1993, pp. 339-342.

- ^ Translation from Wesenberg 1955, p. 65, note 146.

- ^ So for the first time Dibelius 1907, pp. 78–80. A summary of the previous hypotheses on the original installation location of doors is provided by Wesenberg 1955, pp. 174–181. Most recently, Bernhard Bruns ( Die Bernwardstür - Door to the Church . Bernward, Hildesheim 1992, ISBN 3-87065-725-1 , p. 129-136 . ) tries to locate the former location of the door to Saint Michael through symbolic interpretations.

- ^ Tschan, Francis J. Saint Bernward of Hildesheim. 3rd album. Publications in Mediaeval Studies, 13. Notre Dame, Ind .: University of Notre Dame, 1952, fig. 252–255.

- ^ Gallistl 2015

- ↑ Kahsnitz (1993, pp. 503–504) referred in this context to the assumption that the western building of Hildesheim Cathedral was once dedicated to the Archangel Michael , which can also be proven for a large number of other Ottonian and early Romanesque western works. In this way the assumption of the already original destination for the cathedral would be compatible with the inscription on the door itself. This was also the result of Kruse, who in the course of the building archaeological investigations of St. Michael in 2006, due to the nature of the foundations there, did not find any indications for the installation of the doors (Karl Bernhard Kruse: Zum Phantom der Westhalle in St. Michaelis, Hildesheim . In: Christiane Segers-Glocke (Hrsg.): St. Michaelis in Hildesheim - Research results on the architectural archaeological investigation in 2006 (= workbooks on the preservation of monuments in Lower Saxony 34) . Hameln 2008, ISBN 978-3-8271-8034-6 , S. 144-159 . ). A St. Michael's patronage in the west gallery of Hildesheim Cathedral can only be documented in the late Middle Ages. A west gallery only existed there since 1035 (Gallistl 2007/2008, p. 75)

- ↑ Werner Jacobsen, Uwe Lobbedey, Andreas Kleine-Tebbe: The Hildesheim Cathedral at the time of Bernwards . In: Michael Brandt, Arne Eggebrecht (ed.): Bernward von Hildesheim and the age of the Ottonians: exh. Cat. Cathedral and Diocesan Museum Hildesheim, Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum 1993 . tape 1 . Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3-8053-1567-8 , p. 299-311, here p. 307 .

- ^ Karl Bernhard Kruse: The Hildesheim Cathedral. From the imperial chapel and the Carolingian cathedral churches to their destruction in 1945. Excavations and construction studies on the cathedral hill from 1988 to 1999 . Hahnsche Buchhandlung, Hannover 2000, ISBN 3-7752-5644-X , p. 109-113 .

- ↑ Werner Jacobsen, Uwe Lobbedey, Andreas Kleine-Tebbe: The Hildesheim Cathedral at the time of Bernwards . In: Michael Brandt, Arne Eggebrecht (ed.): Bernward von Hildesheim and the age of the Ottonians: exh. Cat. Cathedral and Diocesan Museum Hildesheim, Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum 1993 . tape 1 . Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3-8053-1567-8 , p. 299-311, here pp. 307-309 .

- ↑ Ulrich Knapp: Destruction and reconstruction of the Hildesheim cathedral . In: Ulrich Knapp (Ed.): The Hildesheim Cathedral. Destruction and rebuilding . Michael Imhof, Petersberg 1999, ISBN 3-932526-48-1 , p. 29–92, here pp. 65–71 .

- ↑ Ulrich Knapp: Destruction and reconstruction of the Hildesheim cathedral . In: Ulrich Knapp (Ed.): The Hildesheim Cathedral. Destruction and rebuilding . Michael Imhof, Petersberg 1999, ISBN 3-932526-48-1 , p. 29–92, here pp. 30–31 .

- ↑ https://www.dom-hildesheim.de/de/content/neue-standorte-f%C3%BCr-die-domkunstwerke

- ↑ http://www.schmiedeaachen.de/aktuelles/bernwardt%C3%BCr

- ↑ Drescher 1993, p. 339.

- ↑ Drescher 1993, p. 349.

- ↑ Drescher 1993, pp. 340-342.

- ↑ Dibelius 1907, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Alexander von Reitzenstein: The way of the German sculpture from the early to the late Middle Ages . Self-published by Helene von Reitzenstein, Eggstätt 1994, p. 23 .

- ^ Hermann Beenken : Romanesque sculpture in Germany . Klinckhardt & Biermann, Leipzig 1924, p. 8 .

- ↑ Wilhelm Messerer: The relief in the Middle Ages . Gebrüder Mann, Berlin 1959, p. 19 .

- ↑ Drescher 1993, p. 340.

- ↑ See, inter alia, Adolph Goldschmidt : The German bronze doors of the early Middle Ages . Publishing house of the art history seminar of the university, Marburg ad Lahn 1926 .; Wesenberg 1955.

- ↑ Kahsnitz 1993, p. 512.

- ↑ Drescher 1993, p. 342.

- ^ According to Gallistl 1990. Reference is made separately below to the relevant sources.

- ^ Augustine of Hippo : De civitate Dei, XIII, 23. (PDF, 5.65MB) In: Documenta Catholica Omnia. Cooperatorum Veritatis Societas, 2006, accessed June 30, 2008 (Latin).

- ↑ Petrus Chrysologus : Sermones, LXXX. (PDF, 3.27MB) In: Documenta Catholica Omnia. Cooperatorum Veritatis Societas, 2006, accessed June 30, 2008 (Latin).

- ^ Irenaeus of Lyons : Adversus haereses, V, 19.1. In: Christian Classics Etheral Library. 2006, accessed on June 30, 2008 (english, translation, from, the, latin, from, philip, schaff).

- ^ Irenaeus of Lyons: Adversus haereses, V, 14,1. In: Christian Classics Etheral Library. 2006, accessed on June 30, 2008 (english, translation, from, the, latin, from, philip, schaff).

- ↑ Dibelius 1907, pp. 122–132.

- ↑ The Löwen door pullers of the Mainz market portal are ingredients of the 13th century.

- ↑ Bernhard Gallistl: The Hildesheim bronze door and the sacred model in Bernwardin art . In: Hildesheimer Jahrbuch 64. 1993, pp. 69–86.

- ^ Adolf Bertram : The doors of St. Sabina in Rome as a model for the Bernwards doors . Kornacker, Hildesheim.

- ^ Dibelius 1907, p. 152.

- ↑ Dibelius 1907, pp. 37–41; Carl Nordenfalk. Another touronic picture Bible, in: FS Bernhard Bischoff, Stuttgart 1971, pp. 153–163.

- ↑ 1000 years of St. Michael in Hildesheim, Petersberg 2012 (Writings of the Hornemann Institute, Volume 14), p. 140, note 54.

- ↑ Wesenberg 1955, pp. 68-69; Bauer, Gerd. Notes on the Bernwards Door. In: Low German contributions to art history. 19, 1980, pp. 009-035.

- ^ The portal of St. Paulus, the reduced copy of the Hildesheim Bernward door. In: Sankt Paulus Worms. Dominican Monastery of St. Paul, Worms, archived from the original on October 24, 2008 ; Retrieved June 25, 2008 .

- ↑ Bernhard Gallistl: Meaning and use of the large crown of lights in Hildesheim Cathedral . In: Concilium medii aevi 12 (2009) p. 67 (see p. 50)

- ↑ Gallistl 2007/2008, p. 84, note 26.

literature

- Silke von Berswordt-Wallrabe: volatilization and concretion. The painting by Qiu Shihua - with regard to the Bernward door . In: Michael Brandt, Gerd Winner (Ed.): Transitions | transitions. Gotthard Graubner - Bernwardtür - Qiu Shihua , Hildesheim 2014, pp. 48–57.

- Michael Brandt: Bernwards Door - Treasures from the Hildesheim Cathedral , Verlag Schnell & Steiner GmbH, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7954-2045-1 .

- Bernhard Bruns: The Bernward door - door to the church . Bernward, Hildesheim 1992, ISBN 3-87065-725-1 .

- Aloys Butzkamm: A gateway to paradise. Art and theology on the bronze door of Hildesheim Cathedral . Bonifatius, Paderborn 2004, ISBN 3-89710-275-7 (scope: 162 pages, numerous black and white illustrations, 1 colored leaflet. - Excerpt: The work is mainly devoted to the iconographic and theological interpretation of the scenes, but offers in an introductory chapter also an overview of the current state of research and the historical background against which the Hildesheim Great Bronzes were created.).

- Franz Dibelius: The Bernward door to Hildesheim . Heitz, Strassburg 1907 (length: 152 pages, 3 black-and-white illustrations, 16 black-and-white plates. - Excerpt: Despite the old age, the work is still largely up-to-date.).

- Hans Drescher: On the technique of Bernwardin silver and bronze castings . In: Michael Brandt, Arne Eggebrecht (ed.): Bernward von Hildesheim and the age of the Ottonians: exh. Cat. Cathedral and Diocesan Museum Hildesheim, Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum 1993 . tape 1 . Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3-8053-1567-8 , p. 337–351 (Extent: 14 pages, 14 black-and-white illustrations and graphics. - Excerpt: The article primarily deals with the technical aspects, such as material science and workshop operation, Bernwardin silver and bronze casting. The Christ column and the Bernward door are in the foreground .).

- Kurd Fleige: The symbolic meaning of the tree in Romanesque art - Explained using the sculptures of the Bernward door in Hildesheim . In: the same (Ed.): Church art, capital symbolism and profane buildings: Selected essays on the history of architecture and art in Hildesheim and its surroundings . Bernward-Verlag GmbH, Hildesheim 1993, ISBN 3-87065-793-6 , p. 37–50 (14 pages, 13 black-and-white illustrations - excerpt: The essay deals with the symbolism of the tree representations shown on the door in relation to individual scenes.).

- Bernhard Gallistl: The bronze doors of Bishop Bernwards in Hildesheim Cathedral . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1990, ISBN 3-451-21983-2 (scope: 96 pages, 50 color and 9 black-and-white illustrations. - Excerpt: The work summarizes the current state of research in a condensed form, but no individual references have been made. When describing the individual scenes, the emphasis is on the theological and iconographic contexts: the completion of the creation of man and woman in Christ and his Church.).

- Bernhard Gallistl: The Hildesheim Cathedral and its world cultural heritage. Bernward Door and Christ Column . Olms, Hildesheim 2000, ISBN 3-89366-500-5 (Extent: 145 pages, numerous black and white (detail) illustrations. - Excerpt: The work deals with the production of bronze casts for the Bernwards in Hildesheim. The focus here is on the description of the individual scenes from a theological and iconographic point of view.).

- Bernhard Gallistl: In Faciem Angelici Templi. Cult-historical remarks on the inscription and original placement of the Bernward door. In: Yearbook for History and Art in the Diocese of Hildesheim . 75./76. Volume, 2007, ISSN 0341-9975 , p. 59–92 (Excerpt: author finds the expression "(arch) angelicum templum" as a specific designation of the angelic patronage at the imperial Michael shrine of Byzantium, as well as in Chonai in Asia Minor, the central Michael pilgrimage of Christianity.).

- Bernhard Gallistl: ANGELICI TEMPLI. Cult-historical context and location of the Hildesheim bronze door , in: concilium medii aevi 18, 2015, pp. 81–97; https://cma.gbv.de/dr,cma,018,2015,a,03.pdf

- Richard Hoppe-Sailer: Color - Surface - Body - Space. Gotthard Graubner's painting in dialogue with the Hildesheim Bernward door . In: transitions | transitions. Gotthard Graubner - Bernward door - Qiu Shihua, ed. v. Michael Brandt u. Gerd Winner, Hildesheim 2014, pp. 6–15.

- Rainer Kahsnitz: bronze doors in the cathedral . In: Michael Brandt, Arne Eggebrecht (ed.): Bernward von Hildesheim and the age of the Ottonians: exh. Cat. Cathedral and Diocesan Museum Hildesheim, Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum 1993 . tape 2 . Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3-8053-1567-8 , p. 503–512 (Extent: 10 pages, 3 color tables . - Excerpt: Critical summary of the current state of research with bibliography [for the resolution of the short titles see Volume 1 of the exhibition catalog, pp. 493–522].).

- Karl Bernhard Kruse: To the phantom of the west hall in St. Michaelis, Hildesheim . In: Christiane Segers-Glocke (Hrsg.): St. Michaelis in Hildesheim - Research results on the architectural archaeological investigation in 2006 = workbooks on the preservation of monuments in Lower Saxony 34 . CW Niemeyer Buchverlage GmbH, Hameln 2008, ISBN 978-3-8271-8034-6 , p. 144–159 (Extent: 16 pages, 22 colored illustrations. - Excerpt: Presentation of the excavation results at the west choir of St. Michael.).

- Renate Maas: Bernwards Door as an Event of the Present, in: transitions | transitions. Gotthard Graubner - Bernward door - Qiu Shihua, ed. v. Michael Brandt u. Gerd Winner, Hildesheim 2014, pp. 20–29.

- Rudolf Wesenberg: Bernwardine sculpture. On Ottonian art under Bishop Bernward von Hildesheim . German Association for Art History, Berlin 1955, p. 65–116, 172–181 (190 pages, numerous black-and-white illustrations and graphics, 77 black-and-white plates - Excerpt: Older, but still fundamental work on Bernwardin sculpture, which includes a detailed critical analysis and numerous black-and-white detail shots of the In the appendix, a comprehensive catalog article deals with the technical aspects and the previous location of the door.).

- Michael Fehr: On the iconography and narrative structure of the Hildesheim bronze doors . Bochum 1978 (Extent: 184 pages, 25 drawings by the author. - Excerpt: An analysis of the narrative structure of the representations on the Hildesheim bronze doors is a still little received interpretation of the so far iconographically not clearly clarified first field of the left door leaf as a representation the creation of the first parents, i.e. of Adam and Eve.). / PDF file of the monograph

- "L'arbre & la colonne: La porte de bronze d'Hildesheim" (French) Hardcover - November 22, 2017; by Isabelle Marchesin (contributor), Herbert Leon Kessler (foreword), Editions A&J Picard; ISBN 978-2-7084-1033-6

Web links

- Brief description of the Bernward door on the website of the Diocese of Hildesheim ( Memento from December 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- Detailed recordings of all scenes

Coordinates: 52 ° 8 ′ 56 ″ N , 9 ° 56 ′ 47 ″ E