Buchenwald main process

The main Buchenwald trial was a war crimes trial by the US Army in the US zone of occupation in Germany at the military court in Dachau . It took place from April 11, 1947 to August 14, 1947 in the Dachau internment camp , where the Dachau concentration camp was located until the end of April 1945 . In this trial 31 people were charged with war crimes in connection with the Buchenwald concentration camp and its subcamps . The trial ended with 31 convictions. Officially, the case was named United States of America vs. Josias Prince to Waldeck et al. - Case 000-50-9 called. The main Buchenwald trial was followed by 24 secondary proceedings with 31 defendants. The main Buchenwald trial was part of the Dachau trials that took place from 1945 to 1948.

prehistory

"The pigs in the SS stables received better feed than what the prisoners were fed."

When American troops penetrated further into the territory of the German Reich in the final phase of the Second World War , they were unprepared, sometimes in the middle of fighting, confronted with traces of the atrocities in the concentration camps . Caring for the mostly emaciated and seriously ill “ Muselmen ” as well as burying the prisoners who died on the death marches by exhaustion or shooting , presented the United States Army with a difficult task. Even before the Buchenwald concentration camp was liberated on April 11, 1945, American soldiers had taken photographs after the capture of the Buchenwald sub-camp in Ohrdruf , which illustrate the horrific circumstances surrounding the evacuation of this camp. As early as April 12, 1945, the Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces, Dwight D. Eisenhower, visited the Ohrdruf satellite camp of the Buchenwald concentration camp and asked American and British politicians, representatives of the United Nations and the US press to visit the camp because of the appalling conditions in the camp. On April 16, 1945, 1,000 citizens from Weimar had to inspect the remaining traces of the mass deaths in the Buchenwald concentration camp on the orders of the American commandant; Elsewhere, residents had to bury the dead from the evacuation marches.

Against this background, American investigators quickly began investigations to determine who was responsible for these crimes as part of the War Crimes Program , a US program to create legal norms and a judicial apparatus to prosecute German war crimes. The perpetrators were soon caught and interned, including Hermann Pister , the last commandant of the Buchenwald concentration camp , who was arrested by American soldiers in Munich in June 1945. The commandant's staff were interned in the Bad Aibling prisoner of war camp and interrogated by the Counter Intelligence Corps shortly after the end of the war in 1945 . At least 450 former Buchenwald prisoners were questioned as witnesses, including Hermann Brill , and two truckloads of files from the camp commandant's office were secured. On July 1, 1945, the American military evacuated Thuringia and handed it over to the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SMAD) on the basis of the London EAC protocol . After preliminary investigations against more than 6,000 suspects , around 250 suspects had been interned by autumn 1945. However, witnesses could often no longer be identified or incriminating photos could not be assigned to photographers; in addition, suspects had fled.

Since the Soviet Union had the most victims in the Buchenwald concentration camp in relation to the other affected nations (around 15,000), other suspects were probably staying in the Soviet occupation zone or were in custody there and the camp was now also in the Soviet occupation zone, the American military government in Germany considered leaving the process to the Soviet Union. On November 9, 1945, the Deputy Military Governor Lucius D. Clay submitted the proposal to the head of the Soviet military administration in Germany, Vasily Danilowitsch Sokolowski , that the Buchenwald case be handed over to the Soviet government. After lengthy negotiations and only hesitant inspections of the investigation files, the Soviet side only expressed interest in the proceedings regarding the mass killing in Gardelegen , where almost 1,000 prisoners from an evacuation transport were burned alive in the locked Isenschnibber barn . After the 22 accused and the investigation material had been transferred to the Soviet military authorities, the same procedure was agreed for the accused in the Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora concentration camps , formerly Buchenwald satellite camps and from October 1944 an independent concentration camp. However, the transfer of the internees agreed for September 3, 1946 and the extensive evidence relating to Buchenwald and Mittelbau did not materialize because no representatives of the Soviet military administration appeared at the agreed meeting point at the zone border. After 14 hours of waiting, the prisoners and the evidence were taken back to the Dachau internment camp . The Soviets may not take up this offer because they used the concentration camp as “special camp number 2” after the takeover and therefore feared a lawsuit.

The negotiations on the competence of the Buchenwald proceedings, which were not conducted publicly, were followed by international criticism due to the considerable delays. In particular, the United Nations War Crimes Commission , a commission of allied states to prosecute war crimes committed by the Axis Powers , demanded that the Buchenwald Trial be carried out before an international court of law in early 1946. After the Soviet military authorities showed no interest, the French and Belgian judicial authorities announced the desire to conduct the proceedings. This was rejected by the American side, referring to the immense translation work that should have been done. The lead investigator of the US Army now forced the start of the process. At the end of December 1946, preparations for the trial were completed.

Indictment and Legal Basis

Most accused were members of the former camp staff, but also the Higher SS and Police Leader (HSSPF) Josias zu Waldeck and Pyrmont , who was responsible for the Buchenwald concentration camp. In addition, the camp commandant Hermann Pister and members of the command staff as well as the widow of the first camp commandant, Ilse Koch , were indicted. Three camp doctors and the senior SS medical officer also had to answer in court. Finally there were block and command leaders as well as three prison functionaries and a civilian employee in the dock.

The legal basis of the procedure was formed by the “Legal and Penal Administration”, which came into force in March 1947, based on the military government decrees . The Control Council Law no. 10 were convicted of 20 December 1945 on the basis of those for war crimes , crimes against peace or crimes against humanity were accused played no significant role in this process.

The indictment, served on the defendants in early March 1947, comprised two main charges, which were brought together under the title "Violation of the customs and laws of war". The complaint contained war crimes committed against non-German civilians and prisoners of war in Buchenwald and the satellite camps from September 1, 1939 to May 8, 1945. Initially only crimes against citizens of the Allies or their allied states were prosecuted; Crimes committed by German perpetrators against German victims went unpunished for a long time and were usually only tried in German courts later.

The accused were also charged with a common approach ( common design ) and thus accused of approving participation in a system of killings, mistreatment and inhuman neglect. Therefore, the prosecution had to prove that “ each of the accused was aware of this system, that he knew what was happening to the inmates, and they had to prove to everyone that he was in his place of administration, the organization of the Camp supported the functioning of this system through its behavior, its activity, and its functioning ”. If this evidence was provided, the individual sentencing varied according to the type and extent of this participation. This legal institution was not familiar in the European legal tradition.

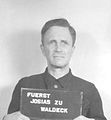

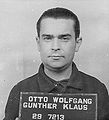

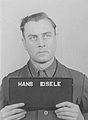

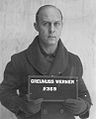

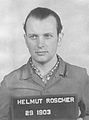

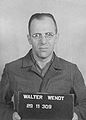

The defendants in photos taken by the US Army in April 1947

Process execution and pronouncement of judgment

"We want to prove in this process that these 31 people were participants in the execution of a joint plan through which members of different nations were exposed to killing, starvation and mistreatment."

After the composition of the military tribunal was established on April 1, 1947, the main Buchenwald trial began on April 11, 1947, exactly two years after the liberation of Buchenwald. The defendants were also imprisoned on the former site of the Dachau concentration camp, where the trial took place. Major General Charles Kiel took over the chairmanship of the military tribunal, which consisted of eight American officers, and Attorney General William D. Denson took over the prosecution. The language of the court was English, and interpreters provided the translation into German . International press reporters were present during the proceedings. American or German lawyers were available to assist the defendants . After the opening speech and the reading of the indictment, all of the defendants pleaded “not guilty”. The hearing of the witnesses and the viewing of the evidence were followed by the statements of the defendants, which were followed by cross-examination .

Six of the defendants were accused of having committed crimes in connection with death marches or in the course of evacuating the camp. The camp doctors and medical staff were charged with mistreatment, neglect, selection and, in some cases, killing of inmates. The commandant's staff was accused of having been primarily responsible for the catastrophic conditions in the camp and thereby creating the system of killings, mistreatment and inhuman neglect. The three prison functionaries, namely a camp elder , an inmate doctor and a senior inmate nurse, were accused of mistreating inmates. The defendants played down the crimes, invoked an imperative to order or denied having been at the scene at the time of the crime. Three defendants in particular were the focus of the national and international public:

- Josias Prince zu Waldeck and Pyrmont was accused of having been primarily responsible for the evacuation of the Buchenwald concentration camp and the resulting deaths due to his function as Higher SS and Police Leader for Military District IX. He stated that he visited Buchenwald about thirty times and entered the protective custody camp a maximum of eight times. In addition, in his opinion, the camp processes and thus the prisoners were outside his area of competence. He also denied knowledge of pseudomedical human experiments that were carried out in the Buchenwald concentration camp. The court was able to prove to Josias zu Waldeck and Pyrmont that on March 31, 1945 he had relocated his office from Kassel to Weimar, where he received an order from the Reichsführer of the SS Himmler to forward the evacuation order from Buchenwald to camp commandant Pister. After forwarding this order to Pister, he supported Pister with the implementation at least organizationally and was thus involved in the crime.

- Hans Merbach was charged with being the head of the evacuation train from Buchenwald, responsible for the more than 2,000 deaths on this transport. In addition, it was proven that he himself carried out or ordered mistreatment and killings of prisoners in the context of the evacuation of the Buchenwald concentration camp. In his testimony in court, Merbach denied having mistreated or killed prisoners. In addition, when the evacuation transport stopped several times, he tried in vain to get food for the prisoners. According to his statement, over 400 prisoners fled during the evacuation transport, between 400 and 480 prisoners died of natural causes and about 15 prisoners were shot trying to escape. The responsibility for the routing of the train and the associated three-week journey time was the responsibility of the Deutsche Reichsbahn .

- The only female accused, Ilse Koch , wife of the camp commandant at the time, who did not hold an official position in the Buchenwald concentration camp, received special attention . She was accused of ordering the mistreatment of inmates and of beating one inmate herself. She also had objects such as book covers and lampshades made from tattooed prisoner skin . Koch stated that he never entered the protective custody camp or hit an inmate. She had no function in Buchenwald concentration camp or was even authorized to issue instructions. She stated that she only lived there as the wife and mother of three children in the living quarters of the SS teams and that she only reported prisoners to the commandant twice for misconduct without considering the consequences. She vehemently denied possessing or ordering items made of tattooed prisoner skin. Ilse Koch could not be proven to be guilty of any objects made from what was supposed to be human skin. However, the court proved to her that she had at least caused severe punishment by reporting prisoners. She was also found to have mistreated a prisoner.

On August 12, 1947, the defendants were given the last word and the opportunity to ask for mitigating circumstances.

Photos of the procedure

Eugen Kogon , a former Buchenwald prisoner, as a witness for the prosecution on April 16, 1947

The 31 judgments in detail

The verdict was announced on August 14, 1947. 22 death sentences were pronounced, as well as five life and four term imprisonment. An illustrated overview of the convicted including their life data also contains the list of the accused in the Buchenwald main trial .

| Defendant | rank | function | judgment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Josias to Waldeck and Pyrmont | SS-Obergruppenführer | Higher SS and Police Leader in Military District IX | Life sentence, converted to 20 years imprisonment on June 8, 1948 |

| Otto Barnewald | SS-Sturmbannführer | Head of Site Administration | Death penalty, later commuted to life imprisonment |

| August Bender | SS-Sturmbannführer | Camp doctor | Ten years imprisonment, later commuted to three years imprisonment |

| Anton Bergmeier | SS-Oberscharführer | Arrest guard in the bunker | Death penalty, later commuted to life imprisonment |

| Arthur Dietzsch | Function prisoner | Kapo and inmate attendant in Block 46 | 15 years imprisonment |

| Hans Eisele | SS-Hauptsturmführer | Camp doctor | Death penalty, later commuted to ten years in prison |

| Werner Greunuss | SS-Untersturmführer | Camp doctor in the Ohrdruf subcamp | Life sentence, later converted to 20 years imprisonment |

| Philipp Grimm | SS-Obersturmführer | Labor leader | Death penalty, later commuted to life imprisonment |

| Hermann Grossmann | SS-Obersturmführer | Camp manager of the subcamps of Buchenwald Wernigerode and Bochumer Verein | Death penalty, executed November 19, 1948 |

| Hermann Hackmann | SS-Hauptsturmführer | Adjutant to the first camp commandant Karl Koch | Death penalty, later commuted to life imprisonment |

| Gustav Heigel | SS-Hauptscharführer | Command leader and head of the arrest block | Death penalty, later commuted to life imprisonment |

| Hermann Helbig | SS-Hauptscharführer | Command leader in the crematorium | Death penalty, executed November 19, 1948 |

| Edwin Katzenellenbogen | Function prisoner | Inmate doctor | Life sentence, later commuted to 15 years |

| Josef Kestel | SS-Hauptscharführer | Block and command leaders | Death penalty, executed November 19, 1948 |

| Ilse Koch | Wife of the former camp commandant Karl Koch | Life sentence, later commuted to four years | |

| Richard Koehler | SS-Unterscharführer | Command leader and supervisor of an evacuation transport | Death penalty, executed November 26, 1948 |

| Hubert Krautwurst | SS-Hauptscharführer | Head of the nursery and sewage treatment plant | Death penalty, executed November 26, 1948 |

| Hans Merbach | SS-Obersturmführer | Second protective custody camp leader and leader of an evacuation transport | Death penalty, executed January 14, 1949 |

| Peter Merker | SS-Oberscharführer | Head of the Gustloff-Werke sub-camp | Death penalty, later commuted to 20 years imprisonment |

| Wolfgang Otto | Staff Scharführer of the Waffen SS | Head of the commandant's office | Twenty years imprisonment, later commuted to ten years imprisonment |

| Hermann Pister | SS-Oberführer | Camp commandant | Death penalty, before execution of the sentence on September 28, 1948 died in custody |

| Emil Pleissner | SS-Hauptscharführer | Command leader in the crematorium | Death penalty, executed November 26, 1948 |

| Guido Reimer | SS-Obersturmführer | Commander of the SS-Sturmbann | Death penalty, later commuted to life imprisonment |

| Helmut Roscher | SS-Oberscharführer | Report leader | Death penalty, later commuted to life imprisonment |

| Hans Schmidt | SS-Hauptsturmführer | Adjutant to camp commandant Pister | Death penalty, executed June 7, 1951 |

| Max Schobert | SS-Sturmbannführer | First protective custody camp leader | Death penalty, executed November 19, 1948 |

| Albert Schwartz | SS-Sturmbannführer | Labor leader | Death penalty, later commuted to life imprisonment |

| Walter Wendt | civilian | Head of HR at Erla Maschinenwerke in Leipzig | 15 years imprisonment, later commuted to five years imprisonment |

| Friedrich Karl Wilhelm | SS-Untersturmführer | Senior SS medical officer | Death penalty, executed November 26, 1948 |

| Hans Wolf | Function prisoner | Camp elder in the Tröglitz subcamp | Death penalty, executed November 19, 1948 |

| Franz Zinecker | SS-Obersturmführer | Labor Service Leader | lifelong prison sentence |

Enforcement of judgments

After the verdict was announced, the convicts were transferred to the Landsberg war crimes prison . Nine of the pronounced death sentences were carried out there on November 19 and 26, 1948 by hanging. Hermann Pister died of a heart attack at the end of September 1948 before the execution of the sentence.

- For Merbach's pardon , his wife, his colleagues from Gothaer Versicherung , residents of his hometown, friends and two American lawyers, as well as former witnesses , campaigned for Merbach's pardon . Nevertheless, Merbach's request for a pardon was not granted, as he had at least proven to have committed murders, even if he was possibly not primarily responsible for the catastrophic conditions of the evacuation transport. Merbach was executed on January 14, 1949.

- The death sentence against Hans Schmidt was upheld even after several review proceedings and finally received nationwide attention. In the Federal Republic of Germany, a campaign to abolish the death penalty began in 1950 , in which high-ranking representatives from society and politics took part. Justice Minister Thomas Dehler asked Federal President Theodor Heuss to submit appeals for clemency to General Thomas T. Handy for Hans Schmidt and Georg Schallermair , who was sentenced to death in a secondary trial to the main Dachau trial . Handy, who had converted eleven death sentences into prison sentences, rejected this request, in Schmidt's case on the following grounds:

“Admittedly, Hans Schmidt was an adjutant in the Buchenwald concentration camp for about three years. [...] He had all the executions of inmates under himself; among them were several hundred prisoners of war who were killed by a special unit, the so-called Kommando 99 . These executions took place in what used to be a horse stable, which was supposed to give the appearance of a hospital pharmacy. When the unsuspecting victims were placed against a wall, apparently to measure their height, they were shot in the back of the head with a powerful air pistol hidden in the wall. Sometimes up to thirty victims were killed in this way. Other executions supervised by Schmidt took place in the camp crematorium; the victims were hung from hooks on the wall and slowly strangled to death. In this case I cannot find any reason for mercy. "

- Schmidt and Schallermair were hung with Oswald Pohl and four other not pardoned delinquents on June 7, 1951 in Landsberg. They were the last death sentences carried out there.

- Ilse Koch, whose life sentence was converted into four years imprisonment, was released from Landsberg in October 1949. One reason was the birth of her fourth child in prison on October 29, 1947. Immediately after his release from Landsberg, Koch was released from the Federal German police arrested and sentenced on January 15, 1951 by the Augsburg Regional Court to life imprisonment for inciting murder and severe physical abuse of German prisoners. After their mercy petitions was not granted, Koch died on September 2, 1967 in the women's prison Aichach by suicide .

The other death sentences and prison sentences have been successively reduced in review proceedings or as a result of appeals for clemency. By the mid-1950s, almost all prisoners convicted in the Buchenwald main trial were released from Landsberg, at least on probation, because of good conduct or for health reasons; So did Josias Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont, whose discharge took place at the beginning of December 1950 for health reasons.

Valuations and effects

In the main Buchenwald trial, as in the other Allied war crimes trials, the constitutional punishment and atonement of Nazi crimes were initially in the foreground. In addition, the population should also be informed about the Nazi crimes and the criminal nature of the acts of violence made clear. Furthermore, these processes should set in motion a collective reflection process in the German population in order to establish a constitutional and democratic culture in post-war Germany and thus in society.

The symbolic process location Dachau, the collective shock of the news and pictures of the violent crimes in the concentration camps reached in the early postwar period in Germany within the meaning of Reeducation initially quite an effect, which can be seen from the numerous contemporary media publications. Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler were soon identified as those primarily responsible for the horrors of the concentration camps ; this shifting of guilt harbored the risk of a subordinate judiciary of the lower classes. This assumption was also promoted by the legal construct of "common design", which is barely comprehensible in Germany , the approving participation in a criminal system that assumed a criminal offense from the outset even without individual evidence of the crime. The American military courts therefore tried to prove that the accused had committed crimes in the Dachau concentration camp trials, which they succeeded in the majority of the cases.

The initial shock of the atrocities in the concentration camps was followed by solidarity from large sections of the German population with the prisoners in Landsberg in the course of the collective displacement. In the course of the Cold War - the Western Allies wanted West Germany as an alliance partner - the successive softening of the sentences and thus the early release of the prisoners from Landsberg began after review procedures. The punishment of the crimes committed in the concentration camps was thus often reduced to absurdity .

Buchenwald secondary processes

The main Buchenwald trial was followed by 24 subsidiary trials with 31 other defendants, which took place between August 27 and December 3, 1947. In addition to 28 SS members, three prison functionaries were charged. The secondary proceedings were based on the same legal principles as the Buchenwald main process and proceeded in a similar form. In contrast to the main proceedings, the secondary proceedings, in which mostly only one or two accused lower-ranking SS members were tried, lasted only one to four days. The mistreatment and killing of Allied prisoners who were committed in the sub-camps, especially on the death marches, were negotiated. In many respects, the proceedings against "Alfred Berger et al." Were an exception, as the subject of the proceedings was the executions by " Kommando 99 ". In addition, this last subsidiary trial was directed against six members of the Buchenwald concentration camp and was carried out from November 25 to December 3, 1947. A total of six death sentences, four life sentences, 15 early prison sentences and six acquittals were passed in the secondary trials . After the verdict was announced, the convicts were transferred to the Landsberg war crimes prison . Of the death sentences pronounced, only that against Adam Ankenbrand was carried out on November 19, 1948 by hanging in the Landsberg War Crimes Prison. As with those convicted of the main trial, the other death sentences and prison terms were reduced in review procedures or as a result of requests for clemency, and the prisoners were released from prison by the mid-1950s.

Two secondary proceedings deserve special attention: on the one hand, the proceedings against Victor Hantscharenko, a former Red Army soldier who was taken prisoner by Germany in 1942. After internment in a POW camp and work assignments in Estonia, Hantscharenko was transferred to the Buchenwald concentration camp in May 1944, where he was assigned to the guard as a Ukrainian SS member. He was accused by witnesses of killing twelve prisoners on the last evacuation transport that left Buchenwald on April 10, 1945. Hantscharenko denied these allegations and alleged that at the time he was accompanying another evacuation transport and, as a Ukrainian SS member, also wore a different uniform than that described by witnesses. The court paid no attention to this evidence, possibly also due to the fact that Hantscharenko only knew Russian. He was sentenced to life imprisonment, attempted suicide and was only paroled in late October 1954.

Furthermore, there were negotiations against Heinrich Buuck, who admitted in court that he had killed prisoners on orders during the evacuation march from the Sonneberg concentration camp external command. The confessed Buuck, clearly identified by witnesses, was considerably less gifted. Nevertheless, he was sentenced to death. However, the death sentence was later commuted to a prison term, also with reference to Buuck's considerable inability to defend himself, due to which he would not have been able to defy his superior's orders to kill. Buuck was granted emergency orders in the review process, so that he was paroled from Landsberg in 1954.

The 24 proceedings and 31 judgments in detail

| Procedure | Defendant | rank | function | judgment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States vs Wilhelm Hinderer et al. - Case 000-Buchenwald-2 | Wilhelm Hinderer | SS man | Use in the Schönebeck subcamp | acquittal |

| Josef Postl | SS man | Use in the Schönebeck subcamp | acquittal | |

| United States vs. Ernst Emil Jackobs - Case 000-Buchenwald-3 | Ernst-Emil Jackobs | SS-Hauptscharführer | Command leader in the Gustloff Works II | 15 years imprisonment |

| United States vs. Alfred Andreas Hoffmann- Case 000-Buchenwald-4 | Alfred Andreas Hofmann | SS-Obersturmführer | Command leader in the Sonneberg concentration camp external command | 5 years imprisonment |

| United States vs Josef Mueller - Case 000-Buchenwald-5 | Josef Mueller | Function prisoner | Kapo in command of the crematorium | Death penalty, later commuted to life imprisonment |

| United States vs Erich Weyrauch - Case 000-Buchenwald-6 | Karl Erich Weyrauch | SS-Oberscharführer | Command leader in the Kassel satellite camp | Ten years imprisonment, later commuted to four years imprisonment |

| United States vs Heinz Blume - Case 000-Buchenwald-7 | Heinz Blume | SS-Oberscharführer | Command leader in the Meuselwitz subcamp | Death penalty, later commuted to three years in prison |

| United States v. Victor Hantscharenko - Case 000-Buchenwald-8 | Victor Hancharenko | Ukrainian SS man | Guard company of the Buchenwald concentration camp | Lifelong prison sentence |

| United States vs Heinrich Buuck - Case 000-Buchenwald-9 | Heinrich Buuck | SS man | Deployment in the concentration camp outside command Sonneberg | Death penalty, later commuted to 15 years' imprisonment |

| United States vs. Ignaz Seitz - Case 000-Buchenwald-11 | Ignaz Seitz | SS storm man | Use in the Leau satellite camp | ten years imprisonment |

| Johannes Volk | SS-Oberscharführer | Use in the Leau satellite camp | ten years imprisonment | |

| United States vs Alfons Kunikowski - Case 000-Buchenwald-13 | Alfons Kunikowski | Function prisoner | Camp elder in the Buchenwald subcamp Laura | seven years imprisonment |

| United States vs. Max Paul Emil Vogel- Case 000-Buchenwald-14 | Emil Vogel | SS member, rank unknown | Use in the Buchenwald sub-camp in Bochum | four years imprisonment |

| United States vs. Adam Ankenbrand - Case 000-Buchenwald-17 | Adam Ankenbrand | SS-Unterscharführer | Use in the Buchenwald subcamp in Schlieben | Death penalty, executed November 19, 1948 |

| United States vs. Friedrich Demmer - Case 000-Buchenwald-20 | Friedrich Demmer | SS-Unterscharführer | Use in the Buchenwald sub-warehouse in Arolsen | ten years imprisonment |

| United States vs Johann Singer- Case 000-Buchenwald-23 | Johann Singer | SS member, rank unknown | Buchenwald Concentration Camp Guard | acquittal |

| United States vs August Giese - Case 000-Buchenwald-25 | August Giese | SS member, rank unknown | Command leader in the Buchenwald satellite camp Laura | four years imprisonment |

| United States vs Paul Mueller - Case 000-Buchenwald-26 | Paul Muller | Function prisoner | Kapo in the Buchenwald subcamp in Bochum | 15 years imprisonment |

| United States vs Ludwig Fisher - Case 000-Buchenwald-31 | Ludwig Fischer | SS member, rank unknown | Deployment in the Buchenwald subcamp Ohrdruf | acquittal |

| United States vs Klaus Ferdinand Huels - Case 000-Buchenwald-36 | Klaus Ferdinand Huels | SS-Stabsscharführer | Deployment in the Buchenwald subcamp Langenstein-Zwieberge | acquittal |

| United States vs Heinrich Zwickl - Case 000-Buchenwald-37 | Heinrich Zwickl | SS member, rank unknown | Deputy commander of the guards in the Buchenwald sub-camp in Zwieberge | Death penalty, likely commuted to prison |

| United States vs Adolf Wuttke - Case 000-Buchenwald-40 | Adolf Wuttke | SS-Hauptscharführer | Command leader in the Schönebeck subcamp | four years and six months imprisonment |

| United States vs Josef Schramm - Case 000-Buchenwald-41 | Josef Schramm | SS squad leader | Command leader in the Buchenwald concentration camp quarry | Lifelong prison sentence |

| United States vs Otto Krause - Case 000-Buchenwald-42 | Otto Krause | SS member, rank unknown | Use in the Buchenwald sub-camp in Magdeburg | ten years imprisonment |

| United States vs Ferdinand Lemke- Case 000-Buchenwald-49 | Ferdinand Lemke | SS-Oberscharführer | Use in Buchenwald concentration camp | acquittal |

| United States vs Werner Alfred Berger et al. - Case 000-Buchenwald-50 | Werner Alfred Berger | SS-Oberscharführer | Head of the personal effects chamber in Buchenwald concentration camp | Lifelong prison sentence |

| Helmut Friedrich Bergt | SS-Hauptscharführer | Labor service leader in Buchenwald concentration camp | acquittal | |

| Josef Bresser | SS-Unterscharführer | Head of Driver Service in Buchenwald Concentration Camp | 15 years imprisonment | |

| Horst Ernst Dittrich | SS-Hauptscharführer | Arms master in Buchenwald concentration camp | Lifelong prison sentence | |

| Wiegand Hillberger | SS-Hauptscharführer | NCO of the camp commandant's office | 20 years imprisonment | |

| Herbert Möckel | SS-Hauptscharführer | Block leaders and trainers | 20 years imprisonment |

attachment

literature

- Buchenwald main trial: Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO 407. (United States of America v. Josias Prince zu Waldeck et al. - Case 000-50-9). Review and Recommendations of the Deputy Judge Advocate for War Crimes, November 1947 Original document (PDF; English; 8.65 MB)

- Ludwig Eiber , Robert Sigl (ed.): Dachau Trials - Nazi crimes before American military courts in Dachau 1945–1948. Wallstein, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-8353-0167-2 .

- Manfred Overesch : Buchenwald and the GDR - or the search for self-legitimation. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1995, ISBN 978-3-525-01356-4 .

- Katrin Greiser: Horror of the Liberators: The US War Crimes Program. In: The Buchenwald death marches. Evacuation of the camp complex in spring 1945 and traces of memory. Wallstein, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8353-0353-9 , pp. 370-450.

- Ute Stiepani: The Dachau Trials and their significance in the context of the Allied prosecution of Nazi crimes. In: Gerd R. Ueberschär : The allied trials against war criminals and soldiers 1943–1952. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-596-13589-3 .

- Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–1948. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-593-34641-9 .

- Wolfgang Benz , Barbara Distel (ed.): The place of terror . History of the National Socialist Concentration Camps. Volume 3: Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-52963-1 .

Web links

- Buchenwald main process and secondary proceedings ( Memento from May 27, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- Landsberg War Crimes Prison

- The SS state - the executioners from the forest of the dead . In: Der Spiegel . No. 16 , 1947, pp. 5 ( online ).

- Video collection of the Robert H. Jackson Center, including film recordings from the main Buchenwald trial (contribution of the Wochenschau Welt in the film to the verdict)

Individual evidence

-

↑ Ute Stiepani: The Dachau processes and their importance in the context of the Allied prosecution of Nazi crimes. In: Gerd R. Ueberschär: The allied trials against war criminals and soldiers 1943–1952. Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 227ff.

Buchenwald Main Trial: Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO 407: (United States of America vs Josias Prince zu Waldeck et al. - Case 000-50-9), November 1947 - ↑ Dr. Peter Zenkl, the 62-year-old Czechoslovak Prime Minister as the first witness in the main Buchenwald trial in mid-April 1947, quoted from: The SS State - The Executioners from the Dead Forest . In: Der Spiegel . No. 16 , 1947, pp. 5 ( online ).

- ↑ a b Katrin Greiser: The Dachau beech forest processes - claim and reality - claim and effect. In: Ludwig Eiber, Robert Sigl (eds.): Dachau Trials - Nazi crimes before American military courts in Dachau 1945–1948. Göttingen 2007, p. 160f.

- ↑ a b c Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–1948. Frankfurt am Main 1992, pp. 111f.

- ↑ Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–1948. Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 16 ff.

- ^ From the affidavit of August Bender in Kreuzau of November 8, 1948.

- ↑ Manfred Overesch: Buchenwald and the GDR - or the search for self-legitimation. 1995, 206f.

-

↑ Manfred Overesch, 1995, pp. 207ff.

Katrin Greiser, 2007, p. 162. - ↑ Katrin Greiser, 2007, p. 163.

- ↑ Buchenwald main trial: Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO 407: (United States of America vs Josias Prince zu Waldeck et al. - Case 000-50-9), November 1947

- ↑ Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–1948. Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 36f.

- ↑ Buchenwald main trial: Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO 407: (United States of America vs Josias Prince zu Waldeck et al. - Case 000-50-9), November 1947.

- ↑ Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–1948. Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 44.

- ↑ Florian Freund: The Dachau Mauthausen Trial. In: Documentation archive of the Austrian resistance. Yearbook 2001. Vienna 2001, pp. 35–66.

- ↑ From the opening speech of the Chief Public Prosecutor William D. Denson in the Buchenwald main trial, April 11, 1947, quoted from: Der SS-Staat - Die Henker aus dem Totenwald . In: Der Spiegel . No. 16 , 1947, pp. 5 ( online ).

- ↑ Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO 407 (United States of America vs Josias Prince zu Waldeck et al. - Case 000-50-9), November 1947.

- ↑ Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO 407 (United States of America vs Josias Prince zu Waldeck et al. - Case 000-50-9), November 1947, p. 36f.

- ↑ Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO 407 (United States of America vs Josias Prince zu Waldeck et al. - Case 000-50-9), November 1947, pp. 70f.

-

↑ Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO; 407 (United States of America vs Josias Prince zu Waldeck et al. - Case 000-50-9), November 1947, p. 63f.

Buchenwald Memorial: Is it true that the SS had lampshades made from human skin in the Buchenwald concentration camp? Answer from Dr. Harry Stein - ↑ The death of Ilse Koch . In: Die Zeit , No. 35/1967.

- ↑ Deputy Judge Advocate's Office 7708 War Crimes Group European Command APO 407 (United States of America vs Josias Prince zu Waldeck et al. - Case 000-50-9), November 1947, p. 2f.

- ↑ Karin Orth: The Concentration Camp SS. dtv, Munich 2004, p. 277.

- ↑ a b Katrin Greiser, 2007, p. 165ff.

- ↑ Jens Bisky : Two classes of people. In: Berliner Zeitung , March 8, 2001

- ^ Quoted from Annette Wilmes : pardon of the Nuremberg war criminals. The declaration of cell phones in full by: Robert Sigel: In the interests of justice. The Dachau war crimes trials 1945–1948. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-593-34641-9 , pp. 179ff.

-

↑ Wolfgang Benz, Barbara Distel (ed.): The place of terror - history of the National Socialist concentration camps. Volume 2: Early camp, Dachau, Emsland camp. Beck, Nördlingen 2005, p. 393.

Landsberg War Crimes Prison - ^ Ernst Klee: Das Personenlexikon zum Third Reich: Who was what before and after 1945. Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 323.

- ↑ a b Ute Stiepani, 1999, p. 232f.

- ↑ Norbert Frei: Politics of the Past. The beginnings of the Federal Republic and the Nazi past. Munich 2003, ISBN 3-423-30720-X , pp. 133–306.

- ↑ Katrin Greiser, 2007, p. 167ff.

- ↑ Buchenwald Cases ( Memento from May 27, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ United States vs Alfred Berger et al. - Case 000-Buchenwald-50 (PDF; 4.6 MB)

- ↑ Ute Stiepani, 1999, p. 230.

- ↑ a b Katrin Greiser, 2007, p. 164f.