Mark Castle

| Mark Castle | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Castle Hill Mark |

||

| Alternative name (s): | House Mark | |

| Creation time : | at or before 1198 | |

| Castle type : | Niederungsburg, moth | |

| Conservation status: | Burgstall | |

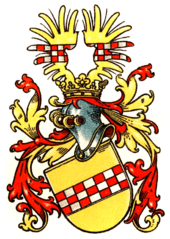

| Standing position : | Sovereign Castle, Count's Seat ( Von der Mark House ) | |

| Construction: | Quarry stone | |

| Place: | Hamm | |

| Geographical location | 51 ° 40 '56 " N , 7 ° 50' 48" E | |

|

|

||

The Mark Castle is an abandoned medieval fortification in Mark ( Hamm-Uentrop district ) in North Rhine-Westphalia .

It was owned by the Counts of Berg-Altena since 1198 at the latest . As the first count , Adolf I of the Mark made the castle his seat and named himself after it comes de Marca (also: comes be Marka ) or modern Graf von der Mark . Since April 3, 1990, the area known today as "Burghügel Mark" has been categorized as a ground monument. Almost nothing is left of the structures of the former tower hill castle ( Motte ).

history

When exactly the history of Burg Mark begins is uncertain. It is unlikely that a large moth was present as early as the 12th century . On the one hand, the erection of a large fortification in the immediate vicinity of the headquarters of the Werl-Hövel line would have been problematic for political reasons. On the other hand, archaeological investigations have so far not uncovered any finds from the 12th century. The actual castle was probably built around 1200. The property at that time was probably a courtyard that was surrounded by a moat .

Rabodo von der Mark and Friedrich von Altena

Friedrich von Berg-Altena is considered to be the builder of the castle complex . The later castle hill belonged to the possessions of Oberhof Mark, the Schultenhof , on whose grounds the Pankratius Church has stood since around 1000 AD . It is very likely that this was first consecrated to another saint, such as Saint Martin. Pankratius was one of the patron saints of the Berg-Altena-Mark family; Pankratius worship was probably only established by these in the region. Accordingly, the Pankratius Church later became the house church of the Counts von der Mark and their castle complex.

Friedrich acquired the Oberhof, the church and the associated possessions (including the castle hill) between 1170 and 1198. The circumstances under which he came into the possession of the former Oberhof Mark and the associated goods is not fully understood. Different versions of this story exist. All sources largely agree that the site was owned by a certain Rabodo von der Mark until around 1170. However, there is already disagreement when it comes to making statements about the person of Rabodo. Some authors say that Rabodo was one of the noble lords of Rüdenberg . After that, the von Rüdenberg family still owned the Oberhof in the Mark in the middle of the 12th century. Towards the middle of the twelfth century, the brothers Conrad and Rabodo shared their paternal estates (probably 1166). The Oberhof Mark fell to the Rabodo. From this time on he used the nickname von der Mark , first mentioned in the Bredelar's deed of foundation from 1170. According to Reinhold Stirnberg, Rabodo von der Mark and the nobleman Rabodo von Rüdenberg are two different people, both of whom were witnesses in a Cologne document from 1169 should have occurred. The nobleman is said to have died as early as 1170, Rabodo before the Mark at the latest in 1178. The historical context speaks against this variant. The Oberhof Mark in the village of Mark near Hamm was the oldest property of the noblemen of Rüdenberg, their allod . There is no evidence that the noblemen von Rüdenberg lost this property before 1170. In addition, it is not possible to make plausible how the Oberhof would have come into the possession of a Rabodo von der Mark who happened to have the same (rare) name as the heir of the Rüdenberg family. Why the Oberhof changed hands in 1170 is easy to understand. Since 1167 Philipp I von Heinsberg was Archbishop of Cologne. Since taking office, he continued his predecessor's policy of increasing power, but intensified their primarily territorial expansion by buying up the castles of his vassals and giving them back as fiefdoms. Philip remained a fiefdom of the emperor and the vassals also ultimately held their territories as imperial fiefdoms, but the direct bond with the archbishop had become stronger through the purchase and rejection. When the emperor died, the continued territorial cohesion of the archdiocese would no longer have been dependent solely on the confirmation of the fiefs by the new emperor. According to Schroeder, Rabodo sold the farm to Philipp von Heinsberg in 1169 due to an acute lack of money. In this way, the Oberhof Mark became the property of the archbishop and Rabodo his vassal. Philipp von Heinsberg has always done similar business. For example, he also bought Nienbrügge from its owner at the time, Arnold von Altena . And Jutta, the daughter of Ludwig V of Thuringia, also sold Neuwindeck Castle to Philipp and was given it as a loan immediately afterwards. It was in keeping with Philip's very common business practice to lend the acquired property to its original owner. In this respect, too, it is plausible that Rabodo von der Mark, the seller of Oberhof Mark, must be identical with Rabodo, nobleman von Rüdenberg, heir to the House of Rüdenberg and Oberhof Mark. Rabodo only parted with the longstanding family property because he knew that he would get it back as a fief.

Philipp von Heinsberg bought the Oberhof Mark from Rabodo von der Mark, nobleman von Rüdenberg, for 400 Marks, whereupon Rabodo received the estate as a fief and became Philip's vassal. In a document dated June 19, 1178, Pope Alexander III confirmed . At the request of Philipp von Heinsberg of the Cologne church, all their possessions, including Burg Mag: Burg Marcha with the entire allod, the free property of Rabodo von der Mark . On March 7, 1184 Pope Lucius III repeated this . The Cologne church was granted Mark Castle with the entire allod of Rabodo and its accessories and servants .

However, only a short time after the sale, probably in 1170, Rabodo von der Mark died. With that the line of those von Rüdenberg died out in the male line; Stirnberg also names the date of death of the nobleman as 1170.

There are various answers to the question of how the Oberhof got to Friedrich. The first is that the sales contract was not worth the paper it was on, and Rabodo sold the property again, this time to Friedrich. This variant should be completely excluded. Philipp von Heinsberg, who was meticulously careful to make the nobles dependent on themselves and to exercise control over their possessions, would never have accepted such real estate fraud at his expense. According to another account, Rabodo only sold his feudal right to Friedrich von Altena - with the consent of the liege lord (in a modification of this assumption, this happened in 1178, which assumes a somewhat longer life span for Rabodo.) The third version is that the archbishop himself Friedrich has enfeoffed the Oberhof. Since Rabodo died shortly after the estate was sold, the Oberhof fell back relatively quickly to the Archbishop of Cologne. Since the male line of the von Rüdenberg family had died out, it was obvious that Philip looked for another feudal man and vassal. Friedrich acquired the Oberhof Mark possibly in the course of Rabodo's year of death 1170, according to another account only at a later date; at the latest, however, in 1198, since the property passed to his son Adolf after his death. And according to a fourth variant, Friedrich von Berg-Altena acquired the property in 1198 through the mediation of his drosten Ludolf von Boenen, optionally from Rabodo, which is excluded, since he was long dead at this late point in time, from Philipp von Heinsberg or from Archbishop Adolf von Altena of Cologne reigned from 1193 to 1205 . If one assumes an early date of birth of Count Adolf (see Adolf I. von der Mark # year of birth ), Adolf I could also have acquired the facility himself, although this is not really plausible during his father's lifetime, since he was the acting count von Altena was the owner of the family property.

It is therefore questionable whether the Archbishop of Cologne only consented to a transfer of the feudal right from Rabodo to Friedrich or whether he enfeoffed Friedrich himself with the Brandenburg goods. What is certain is that Friedrich could count on the archbishop's benevolence. During the feud between Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa and the Saxon Duke Heinrich the Lion , Friedrich von Berg-Altena supported the Emperor and the Archbishop of Cologne. As a result of the dispute, Barbarossa withdrew the rule of the Duke of Saxony over the tribal duchy of Saxony and gave parts of it into the hands of the Archbishop of Cologne, who from now on ruled over the newly created Duchy of Westphalia as Duke of Westphalia . The enfeoffment of Friedrich von Berg-Altena with the Brandenburg area is thus a reward for the loyal service that Friedrich had rendered to the Archbishop of Cologne.

In 1173 Friedrich's father Eberhard I divided the inheritance among his sons, who both called themselves Counts of Altena. The year 1173, often referred to as the year he was born, is actually the year in which Frederick's reign began as Count von Altena. In 1180 Eberhard I died as a lay brother in Altenberg Monastery. At this point at the latest, there must have been a conflict between the brothers Friedrich and Arnold. A bitter dispute broke out over the father's inheritance ( Altenaische inheritance ), which dragged on for years and finally ended in an inheritance that was previously unique and precisely regulated for each individual property. Friedrich is said to have been the trigger for the dispute. The extraordinary nature of this process suggests, however, that the inheritance dispute actually goes back to the work of Philip von Heinsberg, who wanted to prevent the emergence of a large territorial rule in foreign ownership in the vicinity of his new territory. The lengthy dispute must have been concluded by the year Friedrich died (1198 or 1199) at the latest, since otherwise his son Adolf I von der Mark would certainly not have been able to inherit his inheritance as easily as he then did.

Adolf I. von der Mark

Friedrich married Alveradis von Krieckenbeck, daughter of Count Rainer, before 1198/99. His sons were Count Adolf I. von der Mark and Friedrich.

Adolf von der Mark is considered by many historians to be younger than he can actually be on closer inspection of the documents. The year 1194 is often mentioned as the year of his birth because Adolf von der Mark was first mentioned in a document in this year. The document from 1194 shows, however, that Adolf appears as a witness to a legal transaction by his father this year; so he must have already come of age at this point in time. Other indications also indicate that Count Adolf was actually born at a much earlier point in time, possibly around 1181 or 1182 (see the article on Count Adolf I. von der Mark).

From 1181/1182, the presumed year of birth of Count Adolf, the construction of Mark Castle by Adolf's father Friedrich von Berg-Altena would be plausible. Around this time the Altenaische inheritance was completed, which also meant that Friedrich's ancestral castle Altena had become worthless to him. Friedrich's brother Arnold von Altena had inherited half of the castle and later sold his share to the Archbishop of Cologne, in whom Friedrich found an uncomfortable co-administrator. Friedrich could no longer manage Altena Castle alone, which made switching to an alternative location that was his sole possession attractive. Furthermore, Burg Mark was intended for his son Adolf, who would later succeed him as Count von Altena. The castle hill in the Mark also offered itself due to its strategic location. Since he rose in the immediate vicinity of Nienbrügge , which Friedrich's brother Arnold had made his ancestral castle and residence after moving out of Altena Castle, the construction of a castle on this site hindered the territorial expansion of the Altenaisch-Isenberg family branch (Arnold and his son Friedrich von Isenberg ), who was in constant competition with the Altenaisch-Mark family branch of the Berg family (Friedrich von Berg-Altena and Adolf von der Mark).

It is therefore plausible that Mark Castle was not built by Rabodo von Rüdenberg or Count Adolf von der Mark, as some sources claim, but at the instigation of Friedrich. Generally the year 1198 is given for the start of construction. An earlier date cannot be proven, either from sources or from archaeological evidence, although the political situation suggests it. In any case, the castle complex on the large hill in the Mark was built before 1200. As early as 1202, Count Adolf called himself "Count Adolf von der Mark" after his new property.

In some sources there is talk of Friedrich having a castle of Rabodo or the Oberhof Mark expanded or rebuilt into Castle Mark. However, this does not coincide with the archaeological excavations of 1973/1975. Older construction stages than Friedrich's castle could not be ascertained on the castle hill. If there was a castle of Rabodo, you should look for it elsewhere. The Oberhof Mark was also not at this location. Rather, it was called Schultenhof near the Pankratius Church, which was built on its site. If the hill was built at all, it was with a smaller homestead, which at best was surrounded by a moat.

The money for the construction of Mark Castle came from the sale of the Wiseberg parcel near Nienbrügge , which Friedrich's father Eberhard had bought for his son, to the Archbishop of Cologne, Philipp von Heinsberg, a few years earlier (Friedrich may have had the opportunity to hand over the meadow to the Cologne Archbishop also bought the feudal right to Oberhof Mark). Adolf von Altena , the new Archbishop of Cologne from 1193 , gave this parcel back to Friedrich von Altena, just as he returned many of the goods that Philipp von Heinsberg had bought in order to protect the nobles of the region, some of whom were closely related to him, to support. The city of Hamm was later built on the said parcel. Adolf von der Mark had already considered founding a town in the corner between Lippe and Ahse before 1226; a document from 1213 suggests that he may have tried to give the village of Mark town rights. However, this location was far too close to the possessions of Friedrich's relatives, the Counts of Hövel , and their residence in Nienbrügge; the attempt to found a city at this location would have been stopped immediately from Nienbrügge. It was not until Friedrich von Isenberg, the last Count of Hövel, who was entangled in the murder of Cologne Archbishop Engelbert I in 1226, that Adolf von der Mark was able to extend his rule into this area and the Altean lands south of the Lippe Unite possessions under his rule.

In 1226 Count Adolf I von der Mark founded the city of Hamm and gave the citizens of Nienbrügge, which he destroyed as a punishment for the murder, a new home there. He had a fortified count's seat built in the city, the Stadtburg Hamm . Together with its Altenaischen possessions and that of its newly built Blankenstein Fortress, Hamm formed the cornerstone for the later rule of Adolf, which was ultimately to develop into the Grafschaft Mark . In the city of Hamm the knightly servants of the count, the castle men, initially dominated. They lived at Burg Mark and in the city, partly also on their farms outside the city. Burg Mark had a crew of twelve knightly castle men, which was a great deal; Altena Castle only had five and Blankenstein Castle six. Hamm became together with the castle through this prominent position the Vorot of the County of Mark. The Burgmannen in Mark had civil rights in Hamm and thus also the right to elect a council. They lived on their property and were exempt from taxes.

In 1243 the feud (" Isenberger Wirren ") between Adolf von der Mark and Friedrich's son Dietrich von Altena-Isenberg ended , who was able to claim the goods north of the Lippe, including Bockum and Hövel . Dietrich founded the County of Limburg , while Adolf von der Mark brought the County of Mark into being.

County mark

The nearby parish church of St. Pankratius posed a security risk for the castle. There was a risk that attackers would first take possession of the church and use its high keep to bombard the castle. For this reason, Count Engelbert I. von der Mark, in the course of the dispute with the bishops of Münster in 1251, ordered the church tower to be demolished and replaced with a less tall structure. To compensate, Engelbert left the Schmehausen estate to the Church of the Mark.

The castle was first mentioned in writing as castrum in the years 1256 and 1265. During these years, documents relating to Welver Monastery were issued at the castle. The maintenance of the building was the responsibility of the lord of the castle. In contrast, the residents of the associated office were obliged to carry out the earthworks, such as cleaning the trenches (documented for the year 1599). A document from 1575 shows that those obliged to carry out the necessary work occasionally had to be warned. During the work, the lord of the castle was obliged to feed the workers. To clean the trenches, barges were used with which the workers drove over the trenches.

Until 1391, Mark Castle was the headquarters of the Counts of the Mark . In the 13th century there was a strong team of around 10 to 15 castle men. From this number it can be deduced that no special apartments have been built for them on the outer bailey; there was no room for so many houses there. It can therefore be assumed that they lived together with the lord of the castle in the main castle and did not run an independent household there. They were given orders by the Count personally or by his deputy, the Drosten. The castle men formed a cooperative that had its own seal (a low castle wall with a tower on an ornate ground, on it a pole with a flag on which the coat of arms of the castle lord was included) and had defined rights and duties. In 1393, Count Dietrich II confirmed all rights of the castle team. Above all, this includes the privilege of not being subject to any jurisdiction other than that of the sovereign himself or that of his deputy. Disputes between the castle men or between castle men and their master were heard in the castle court, which was held by all comrades outside the castle in front of the tree courtyard or on the outer bailey in front of the chapel.

Duchy of Cleves

In 1391, after the union with the county of Kleve , the counts moved their residence to the Lower Rhine . After the relocation and the associated reduced use, no new buildings were built. Conversation was also neglected. In 1437, under Count Gerhard von der Mark zu Hamm, Hamm became a royal seat again for a short time (until 1461), but he chose the city castle of Hamm as his residence. Finally, in 1507, the Burgmannen also left Haus Mark to settle on their estates.

From 1450 until the end of the 16th century, House Mark was constantly under pledge . The dukes of Kleve pledged the castle to various pledge holders who tried to earn as much money as possible by leasing the individual pieces of land. The creditors were obliged to maintain the castle (documented, for example, for 1525 and 1599). In practice, however, the pledges were only interested in making as much money as possible and gradually let the building fall into disrepair.

In 1464, Johann I , Duke of Kleve and Count von der Mark, a member of the Torck family , commissioned Lubert Torck (see also the article on Haus Nordherringen and the von Torck family ) to preserve the Mark. Torck was supposed to keep and feed eight defensive men on the premises. The sovereign paid a sum of 12 Rhenish guilders for each man as maintenance.

In 1507 Mark Castle passed to Heinrich Knippink, droste of the Hamm office and judge of Hamm . In 1524/25 he was followed by Evert (Eberhard) von der Recke as pledge holder, then, in 1566 or later, his son Johann, who was married to Anna Overlacker in childless marriage and is still attested on the property in 1578. After him, his nephew Dietrich Overlacker, bailiff of Altena and Iserlohn, held the lien, which was ultimately worth 9075 Reichstaler.

In the 16th century there was no longer a castle garrison because the duke wanted to save maintenance costs. Only in the event of armed conflict should a crew be moved there to protect against attack and devastation (documented for the years 1599 and 1601). In 1595 a site inspection showed the poor condition of the castle. The long stable in the outer bailey was in ruins and overturned by a strong storm. At the chapel, the masonry had moved over a foot from below to under the roof. The long needle on the main castle was also badly dilapidated. Since the roof showed severe damage and it could rain through, the shelling was rotten both above and below. The wooden stairs in front of the house were unusable. The battlement on the curtain wall was completely dilapidated. The gates and bridges were in a similar condition. The conclusion of the visit was that it was impossible for the lien holder to preserve the fabric of the building. He was certainly not able to settle his servants here or manage the area properly.

Shortly before 1600, the last Count von der Mark owed the Reck family so much that he had to leave the castle to them for a sum of 1,500 Reichstalers. This was intended to compensate for any arrears in salary, clothing and other capital.

In 1601, Dietrich Overlacker transferred the lien to his sister Margarete, born with the approval of Duke Johann Wilhelm von Kleve. Overlacker, the widow of Engelhard Spiegel at Desenberg Castle near Warburg; the deposit at that time was 9075 thalers. Margarete in turn left the pledge to her daughter Dorothea, wife of Jobst von Landsberg zu Erwitte . From then on, his descendants became owners of the Mark house without living in it, which the increasingly dilapidated castle house offered little incentive to do. The Lords of Landsberg first tried to repair the castle. They mended the walls, made the rooms habitable, put in new windows and the like. However, the work was interrupted after 1609 by constant armed conflicts, including the Jülich-Klevische Succession dispute and the Thirty Years War . Jobst von Landsberg reported in 1669 that House Mark would have been repaired had it not been repeatedly occupied by enemy garrisons, including Spanish and Dutch.

Instead of the interest of 9075 Reichstalers, the barons of Landsberg had the usufruct of the house of Mark. However, they did not exercise it themselves, but had leased the estate (at least from 1622) for 500 Reichstaler annually.

Brandenburg

Like the entire Duchy of Kleve including the County of Mark, the castle came under Brandenburg rule after the death of the last Count von der Mark in 1609.

From 1616 it served as a prison (probably the vault in the hall). The story of a hammer citizen has been handed down, who was arrested in the Münsterland and brought to the prison in Wolbeck Castle , where he was supposed to be tortured. After his wife turned to the Brandenburg Elector Georg Wilhelm , he ordered from Kleve on February 22, 1616 that a captain with the necessary number of soldiers invade the parish of Heessen, take nine or ten wealthy farmers hostage and take them to the Burg Mark should bring them to use as leverage in the negotiations for the release of the prisoner. Georg Wilhelm instructed the soldiers to treat the prisoners as one would treat the Hammer Bürger in Wolbeck.

On January 7, 1617, Elector Georg Wilhelm ordered the repeal of the Mark Castle pledge. But the Thirty Years War began the following year, so that this matter could no longer be finally settled.

During the Thirty Years War, Mark Castle fell into disrepair due to looting. Although the building no longer had any real military significance, it was occupied several times by rival troops. Between 1622 and 1624 House Mark passed into the hands of various occupiers who were responsible for the renewed destruction of the landsberg repairs. After the intruders withdrew, the Landsbergers made further improvements. Nevertheless, the tenant had to report in 1631: The walls on Burgplatz have broken out and are in disrepair, rooms have been destroyed, wood and lead have been arrested. The kitchen and the other rooms, including the count's make-up, were also completely destroyed by breaking out large stones. The gatekeeper's house has been demolished, the Bauhaus and the stable are pretty dilapidated, fences, forecourt and chapel, walls and walkways have been put down. Another report, a few months later, noted: the kitchen and rooms there were all destroyed, stairs and doors smashed, the glass windows removed and destroyed. Boards, beams and containers broken off and burned, as well as the church door. The sheepfold has broken, the beams, fences, posts and trees have been cut down and burned. In 1632 the Hessian-Imperial war shook the region. The Bavarian Field Marshal Graf von Wahl attempted that year to ruin the Sergeant General Luttersheim and his regiment. He deployed ten companies of foot soldiers who made sure that his opponent did not receive any wood or other goods deliveries. As a result, all the wooden parts of the castle including the boards and doors were gradually burned. After this massive destruction, it was no longer possible to preserve the building.

Regardless of this, the outer bailey initially remained as a commercial enterprise. After the end of the war (1648), the Brandenburg authorities tried to generate income from Haus Mark and the associated goods despite the pledge. The income exceeded the usual interest on the pledge, so the electoral councilors Moßfeld and Ludowici demanded an explanation from the pledge holder or his administrator in 1682 as to how much the electoral rentkeeping was going to pay annually. In the event that payments are not made or are too low, public leasing has been promised.

However, even after the redemption of the House of Mark, no funds were made available for the maintenance of the buildings. All the more so as the kings of Prussia and their representatives used to stay at Renteihof in Hamm on their travels to the western provinces.

In 1684 the government took the position that the leases and other income not only covered the interest and the entire pledged capital, but that a total surplus of 3,082 Reichstalers had been achieved. As a result, she moved the estate and in 1686 had her local landlord put it up for lease. The barons of Landsberg disputed the accuracy of this account and tried repeatedly to claim 4,650 Reichstalers for their part. A related idea was finally rejected in Berlin in 1791 (sic!).

In 1688 House Mark still owned 369 1/2 acres, 23 rods and 180 Schuh hammsches Maß (including wood).

After the 17th century, the castle chapel, built under Adolf I and consecrated to Saint Anthony, served the Reformed as an emergency church.

With the increasing decline of the castle complex, the population and later also the government began to use the main castle more and more often as a quarry; there was a shortage of bricks in this area. In 1772 General Karl Friedrich von Wolffersdorff had the remains of the building demolished in order to use the stones to build the barracks at Hammer Westentor (which no longer existed). A total of 130 truckloads of stones were carried away. In 1774 the barracks could be completed.

In 1777 Burg Mark was given a long lease as a domain estate. The first owner was the Amtsrat Then Bergh.

In 1803 some vaults still existed, which, as relevant finds show, even served as a forger's workshop (local three-penny pieces) in the first half of the 18th century. Like the foundations of the castle, they were almost completely removed this year.

In 1819 the land was sold by the state to the major and domain rent master Vorster, who in 1824 also acquired the neighboring Kentrop monastery .

Prussia and the Federal Republic of Germany

From 1819 to 1935 (alternative information: 1938) the property was privately owned and is now owned by the city of Hamm. After the wars of liberation, Domainrentmeister and Major a. D. Johann Vorster the area. He also acquired Kentrop House in 1824 . In 1851 the fiscal rights were replaced with 14,100 thalers. Johann Vorster's daughter-in-law, widow of Premier Lieutenant Wilhelm Vorster and later wife Ferdinand Graevemeyers , sold both properties to the owner of Haus Caldenhof , Richard Loeb († 1906). His son Otto Loeb († 1923) bequeathed Haus Mark to his granddaughter Gerda Brockmann , born in 1918, on the basis of the law on the dissolution of family estates ( Fideikommiß ) . Black. This eventually sold it to the city of Hamm.

Until the 1930s, the outer bailey was still partially occupied by farm buildings.

In 1973 and 1975 excavations took place, during which only extensive destruction of the archaeological findings could be determined. This means that one of the largest moths in Westphalia is permanently withdrawn from further research.

Oberhof Mark

The Oberhof Mark in the peasantry of the same name and all of the lower courtyards belonging to him belonged to the castle . The owner of House Mark was therefore entitled to the upper ownership of the common Mark, in which these farms were entitled. That gave him the right to dispose of the trademark reason.

All animals kept at Burg Mark had the right to use pasture. Furthermore, the lords of the castle had fishing rights in the Geithebach (up to the village of Schmehausen) and in the Lippe. Nobody else was allowed to fish or hunt ducks in these waters (documented for 1599). The lords of the castle were also responsible for free pigeon breeding. It is reported that in 1567 a hammer citizen who disregarded the prohibition to shoot pigeons had his rifle removed as a punishment. The owners of the House of Mark also had the right to hunt, not only for the court seeds, but in the whole of Hamm .

location

The remains of the Mark Tower Castle (also called House Mark) are today in the urban area of Hamm ; the village of Mark was incorporated into Hamm in 1939. The castle site is located in the flat valley of the Ahse , to the north of the confluence of the Geithe brook into the Ahse, the course of which is now canalized.

The castle hill, on which the outer bailey of Mark Castle was once located, is accessed from the northeast via a 200-meter-long dam over which a pedestrian and cycle path runs. This reaches a little north of the village and the parish church of St. Pankratius in the Mark the Hamm-Soest (Soester Strasse) road, which follows the edge of the valley on this section.

Historical appearance

With a total length of 200 meters, Mark Castle was one of the largest moths in Westphalia. The Counts von der Mark designed it in two parts. In addition to the main castle , there was a bailey, which was connected to the Hamm - Soest road in a north-easterly direction via a 200-meter-long dam . This path was the only access to the castle. It was blocked by a barrier at the outer moat. A bridge led across the moat to the inner wall. That was where the front gate stood. Behind it a second bridge crossed the inner ditch up to the main gate, a mighty stone building. Like the foremost gate, this was specially secured by a drawbridge .

The main and outer bailey were surrounded by a moat (now filled in) , which was lined with a flat earth wall. This was later planted with hops and vegetables and sown with grain. The division of the site was achieved by a trench in which the two ring trenches converged. Both parts were surrounded by a wall with a battlement .

In the vicinity of Hamm and the Mark there are no quarries from which building material for the walls could have been taken. Nevertheless, the buildings have dimensions that are also unusual in view of the time of construction. The facades were presumably whitewashed, a further reinforcement of the apparently impressive overall impression of the castle.

Information about older construction stages is obtained from a total of eight cards. Before the Second World War, these were summarized in the Arnsberg land registry office in a 61 × 54 centimeter, eight-sheet atlas with outlines of the tenants of the Hoggravial House of Mark . Sheet 1 to 7 was drawn on March 15, 1688 by the local mathematicus Kuyper, while sheet 8 was made in 1751 by the engineer Meinicke.

In addition, an inspection report from 1595 is to be used as an important testimony to the building design.

According to the recording from 1688 and the description from around 1600, reproduced by both Lappe and von Flume, the castle grounds were surrounded by a wide ring moat and two high ramparts, likewise bordered by moats. All the trenches were connected to each other and were fed by the Ahse and Geithe. The barrier still existing in 1688, the two drawbridges and the stone gate have disappeared from the map from 1751.

Main castle

The mound of earth of the main castle is about seven meters high and had a diameter of 50 to 60 meters.

It is a so-called ring - mantle castle . Weir systems of this type are characterized by the fact that the hill foot of the main castle is surrounded by a wall. The buildings leaned against the curtain wall inside. The dominant building of the main castle was a two-story, tower-like hall ( donjon ) with a floor area of 18.2 × 9.7 m (58 feet long, 31 feet wide) in the southwest of the complex (the residential building). During the aforementioned tour of the castle in 1595, this building was referred to as the Langhe Sadel or our G. F. and Mr. Sadell .

After this description was Palas basement of a vaulted basement, which had, however, been necessary even at this time of renewal: The muihrmeister but beduncken can be, weilln under this sattell a high Reisiger stable and therefore a high gewelffte (vault) tolerate wanted shalt muighen That such a blasting underwelbet with XM (= 10,000) brick and 6 foihr clacks ... In translation this means that the hall had a high, arched basement or cellar, which should be arched with 10,000 bricks. There is also talk of a more wooden bustard (wooden staircase) in front of the palace. External stairs and galleries made of wood connected the two floors of the palace, which rose above the vaulted basement. Uff this overstepping room there are terrible old wooden parts, the rest of the things are pasier, the galleries as well as the whole house baker, that is to say, Johan von der Reck tend to live in, is (are) completely through and must never dock, put in front, hang up pans become…

The plan from 1688 shows, in addition to the palace, the surrounding wall with battlements and two towers embedded in it, of which the eastern one includes a gatehouse . These buildings of the main castle can no longer be seen on another plan from 1751; so they probably fell victim to the demolition work of the 18th century. At that time only remnants of the curtain wall and the eastern tower existed. The western keep has completely disappeared.

The gatehouse was in the east tower, a 12 × 9.5 m building on the east side of the main castle. During the excavations, a large excavation pit was discovered here, which used to be the entrance to the main castle. According to the width of the excavation pits, the ring wall was about 1.5 to 2.0 meters wide. The wall had been placed in the top of the hill. In the course of the construction work, it was partially filled in from the outside.

Wooden buildings were no longer detectable during the archaeological excavations, so the statements about the structure of the main castle are incomplete.

Outer bailey

The outer bailey has an irregular oval floor plan and measures around 140 × 100 m. It was two meters above the site and joined the main castle to the northeast. Both plants were connected by a wooden bridge. The piles of this bridge were found during the archaeological excavations.

In contrast to the multi-storey, seven-meter-high main castle, the outer bailey only reached a height of two meters. The outer bailey was also enclosed by a wall.

Little is known about the late medieval development. The older map names some of the buildings, but it is not particularly accurate geodetically. A gate with a drawbridge can be seen on the outer bailey. A two-part farm building is to the south of the facility, the long stable 102 feet long and 24 feet wide. It was built of bricks and used the south wall of the castle as a wall.

A chapel is drawn to the north of it, probably the Antonius Chapel, founded in 1442, which is one of the few buildings in Mark Castle that is documented for 1595. She was 49 feet long and 24 feet high. A chapel already existed here in medieval contexts so that the defenders were not forced to visit the neighboring parish church in times of war and thus expose themselves to the risk of capture. The chapel is still shown on the map from 1688; it can no longer be found on the one from 1751.

Between the stable and the castle chapel stood the farm buildings (the tenant's house, barn, stables, etc.), to which the former accommodation of the castle men had been expanded over time. In 1751 only the “long stable” and two other farm buildings were left on the outer bailey.

To the south of a tower, an entrance led over the divorce ditch to the main castle, which was also called the Upper Palatinate because of its elevated position .

A second tower is embedded in the curtain wall.

The more recent development is clearly evident in the plans from 1688 and 1751. On the map from 1751, farm buildings can be seen on the southern edge of the outer bailey. The inner strength was already filled up.

The stone fountain on the outer bailey, which can still be visited there today, has been proven to date back to the 19th century, but the exact time of its origin is unclear.

The area north-west of the outer bailey was called the old garden in 1751 , in contrast to the large garden in the northern part of the bailey. The same area appears on the older map as the Great Garden is so anizto plucked . It should therefore have been the medieval kitchen garden of the castle.

The description from 1595 mentions the Vorburgtor, indt four-sided with stone ; a long stable, built of bricks and placed on the south wall of the outer bailey, 102 feet long, 24 feet wide, but already overturned; further north of it is the chapel, 47 feet long by 24 feet high.

Ditches and moats

The main moat is surrounded by an outer wall . A narrow, mostly double ditch runs around this, which borders a path on the south side. The double moat is apparently not a moat. Rather, it is reminiscent of the drainage ditches that run between the paddocks. On the older map the double ditch is mentioned under the signature 14: the other whale around the house over which a footpath goes .

Current condition

Mark Castle is now an important monument of Westphalian regional and cultural history. The castle hill and its surroundings are designed as a recreational area. The current condition of the facility essentially corresponds to that shown in the original cadastre from 1828. Bomb craters and excavation of the moats to set up a fish farm are recent changes in the area.

The current facility is a park that is enclosed by the former moats of the main castle (Motte) and the economic or outer castle. An approximately oval moat surrounds both parts of the castle. The smaller, circular main castle is also cut from the oval by another, partially filled in trench. The area of the outer bailey is today about 2 m above the surrounding meadow landscape. The platform of the truncated cone-shaped main castle hill is a good 7 m above the surrounding area. The castle complex can therefore be assigned to the type of moth and is considered the largest and best-preserved moth in Westphalia . Around the oval moat there is still a heavily sanded wall remnant that rises about half a meter above the surrounding area.

The area of the outer bailey is overgrown with trees. Here is a historic well shaft that was reconstructed with the help of the remains of a well found in the city of Hamm. A wooden pavilion is available for hikers and cyclists; the surrounding, paved area can also be used as a barbecue area. Almost nothing is left of the medieval buildings.

A wooden bridge and the adjoining wooden staircase lead up to the former inner courtyard of the main castle. The wreath of a circular wall and a tower drawn with a compass can be seen there. The space between the walls is covered with trees.

According to the results of the excavations in 1973 and 1975, in the jubilee year 1976, when Hamm celebrated its 750th anniversary, the approximate location of the building, interpreted as a palace (possibly also a donjon ), was indicated by masonry in the ground on the motte . Next to it there is a memorial stone that was built up in 1976. A memorial plaque was also erected.

In 2009, the Hamm-Uentrop district council redesigned the entrance area and the stairs of the Motte with the help of sponsorship money. New information boards inform visitors to the park about the historic site.

Further development of use

The castle hill is only available to a very limited extent as an event area. In principle, only those activities are possible that do not endanger the property of the castle hill as a ground monument. For larger events, there is also a lack of the necessary infrastructure (electricity, water and sewage pipes as well as toilet facilities), which would have to be replaced by appropriate mobile solutions. However, since the city administration fears the occurrence of ground damage, for example in the context of the delivery of the required systems by trucks, no approval is usually given.

The use of the castle hill is accordingly limited to traditional events. This includes the annual open monument day , the ecumenical service of the Hamm-Mark shooting club and graduation ceremonies. The castle hill is used as a park and crossed by various cycling and hiking trails.

Incidentally, the area was paid little attention to the city and Hammer citizens for a long time. The remote location of the castle hill and the lack of lighting in the area in the shade of tall trees have repeatedly led to safety and cleanliness problems in the past. Particularly noteworthy here are nightly vandalism and uncontrolled waste.

In 2007, the citizens' interest group Burg Graf Adolf von der Mark was formed, which encouraged further use of the castle hill area. Your original idea of building a reconstruction of Mark Castle on the site soon had to be abandoned. The lack of knowledge about the medieval state of construction of the castle forbids an exact reconstruction; moreover, such use would contradict the land monument property of the castle hill, which the community of interests also intended to protect.

On June 27, 2008, the community of citizens' interests was transferred to the "Burg Mark" Hamm eV association. The purpose of the association is the redesign and upgrading of the ground monument and the park around the castle hill, the promotion of historical awareness (city history and founding of the city of Hamm), the maintenance of the ground monument "Burghügel Mark" and the promotion of the cultural and social coexistence of the citizens of the city Hamm.

The development association under its founders and chairmen Uwe Richert and André Wolter opened a dialogue between the citizens of Hammer and the city of Hamm about the future use of the castle hill. As a result, design measures were carried out on the castle hill for the first time in years. The city succeeded in finding sponsors , namely the Hamm-Uentrop district council under district chairman Björn Pförtzsch, who financed the renovation of the stairs between the outer and main castle and further information boards. The construction work was carried out in autumn 2009.

In February 2010, the old poplar trees from the castle hill had to be removed from the point of view of road safety. Legislative requirements to ensure a suitable replacement, but also the intense debate that followed in the local press, gave an opportunity to discuss the further design of the castle hill in a wider circle. In May 2010, the Burghügel Mark working group, consisting of politicians and administrative employees, local homebuilders, representatives of the Marker and Ostenfeldmarker associations, the Burg Mark development association, the Mark pedigree breeding association and interested citizens met. A joint maintenance and design concept for the castle hill area was developed in several meetings.

On September 2, 2010, the Uentrop district council passed the draft resolution "Burghügel design concept". This forms the basis for taking the castle hill adequately into account in future budget discussions. This has already been done in the past for the Hamm Kurpark .

The area in the entrance to the outer bailey, on which the riding school “Ute's small farm” operated by Ute Maßjosthusmann was located, was also included in the planning. Since then it has been trying to move to another area. The stable building, which is in a poor structural condition, is to be removed and the entrance area to the outer bailey is to be redesigned to a large extent.

The Friends' Association of Burg Mark would like to erect a memorial to the town's founder, Count Adolf I. von der Mark, on the castle hill. The planned sculpture finds a historical model in the Nagelgrafen , a sculpture by the artist Leopold Fleischhacker , which, like other nail figures in other cities, served to acquire donations for war invalids and the relatives of war victims and to increase the acceptance of the war among the population during the First World War .

As a specific measure on the part of the city, it was decided to plant new trees to replace the poplar trees that had been removed. This was partially implemented in spring 2011. Of the more than 80 planned trees, twenty-three have actually been planted so far.

Archaeological research

In the 1930s, ground interventions took place, during which a bronze spur could be secured on the main castle.

In 1973 and 1975 Uwe Lobbedey carried out extensive, well-documented excavations at Mark Castle. He had set himself the task of locating the known components (ring wall, tower and hall) and looking for traces of any further interior development.

Lobbedey also examined the question of whether several construction stages can be distinguished. He was thinking above all of the former Oberhof Mark or a possible castle complex owned by Rabodo von der Mark. As is well known, the Counts von der Mark later expanded and enlarged the facility considerably.

The excavations carried out by Lobbedey resulted in the total loss of the building fabric. The former buildings have been broken out with the foundations. The resulting disturbances can be seen as evidence of the earlier buildings, but do not provide any information that goes significantly beyond what is already known from the plans.

The deep-reaching modern earth movements have permanently destroyed all indications of construction phases or usage horizons.

The mound of the main castle

The embankment of the truncated conical hill of the main castle consists of yellowish-brown or yellow sand. There are also layers enriched with charcoal or humus intermediate horizons. There are no finds to be recorded that would prove the existence of an older building (i.e. the Oberhof Mark or the property of Rabodo von der Mark). The existing subsoil consists of silty alluvial clay; the sandy filling material of the hill must have been brought from elsewhere. The sand heap was largely disturbed. Where this is not the case, it is about 40 cm below today's surface, which is in the middle area at about 66.00 m above sea level. On the eastern edge of the hill, the foot of the discharge was cut at a depth of 60.50 m above sea level. In this eastern section, the foot of the hill merges into the moat without a step. It was not possible to determine exactly where the bottom sole was. At a depth of 58.20 m above sea level (about 3.10 m below ground level) it had not yet been reached. The moat is filled with a gray, peat-like mass. The filling is cut off towards the hill. There is a 6-7 m wide excavation there. It appears to be a partial restoration of the moat, which in turn is filled with clay, sand and rubble.

The curtain wall

Like all the foundations of the castle, the masonry of the curtain wall was broken off in the 17th and 18th centuries. Only a small remnant of the foundation remains on the north side of the wall. This consists of one or two layers of flat, bonded, green marl quarry stones, which have been connected by hard, whitish lime mortar mixed with fine sand. The excavation pit is around 2.50 m wide and filled with earth and rubble. The lower edge of the excavation pit is at a height of about 62.5 m above sea level, i.e. a good 3.40 m below the surface of the hill. About 1 m outside the foundation, a small pit was cut in the depth of the foundation floor, filled with slightly humus stone and some charcoal. This presumably dates back to the time of the construction work (around 1198). In the western section, their width is 1.70 to 1.80 m.

The sand filling outside the curtain wall was mixed up with scattered bits of mortar several times. About 40 - 60 cm above the lower edge of the foundation, the approximate, horizontal border between the pure sand and the mortar mixed could be located. The find indicates that the top layer of mound outside was only heaped up after the foundations had been built.

At a further intersection one can find such a layer interspersed with lumps of mortar on the inside of the wall ring. Its lower edge is 1.60 m above the base of the foundation.

Otherwise there is no evidence of palisades or other additional fortifications.

The hall

In the northwestern part of the hill palace, Lobbedey has uncovered deep excavation pits of a larger structure. Some of these pits only came to light after the 1.10 to 1.70 m deep, secondarily dug up earth layer had been removed. In the near-surface layers they are filled with humus soil and building rubble, in the lower-lying areas they are mostly filled with sterile sand that has slipped into the mound. The lower edge could be located in two places. For the east-west section it was determined at 63.46 m above sea level, at a second point at 63.53 m above sea level, i.e. 2.40 m below the current hill surface. At a third intersection, the only masonry that remained in its original position was discovered. It is a single-sided wall made of rubble stones (green marl and limestone) and red and yellow bricks, built to the north and east against the mound, bent at right angles. These are connected by light-colored mortar and are around 35 - 60 cm thick. To the west, loamy and humus soil and rubble were filled in to a depth of 64.28 m above sea level. This angular brickwork was apparently the side wall of a basement entrance.

The eastern tower

Most recently, Lobbedey tried to locate the tower that was marked on the maps from the 17th and 18th centuries with the help of several sand cuts. These studies proved to be particularly problematic. The soil is difficult to penetrate at this point, as it consists of thick layers of layers of loamy and humus soil or rubble. This fact indicates that stone material was removed from the castle from here. Several backfilled pits were possibly search trenches for the detection of foundation masonry. Lobbedey was also able to record that the outer edge of the mound had been largely eroded here. It was not possible to conclusively clarify whether this was intended to produce sand or whether it was used to fill the moat. Only a deep excavation pit was clearly visible, the lower edge of which had not yet been reached at a depth of 63.03 m above sea level, i.e. about 3 m below the surface of the hill. It should be the north wall of the tower we are looking for.

reconstruction

On the map from 1751 the curtain wall forms an exact circle. Whether this corresponds to the actual conditions on site cannot be verified, as there is no excavated clue on the south side. There are, however, four sites of the circular wall that make an almost exactly circular course of the wall more than likely. An older fortification system, no matter what type, is not recognizable without this circular wall.

The approximately 2.40 m deep excavation pit in the northwestern part of the hill area corresponds to the long needle of the description from 1595, the dimensions of which are given as 58 feet in length and 31 feet in width, which corresponds to about 18.20 and 9.70 m. As far as these dimensions are exactly correct, the hall and the curtain wall were separated by a space - albeit not particularly large. The only remaining masonry is that of the cellar entrance. With its help, the alignment of the wall can be determined.

One problem has not yet been resolved. In the section leading to the west, a turn of the excavation pit to the northeast in the direction of a second, clearly recognizable excavation pit could not be determined. This can only be explained by the fact that the front wall of the hall was less solid than the side walls. That would be conceivable, but only if the high vault , which the description from 1595 mentions and which was to be vaulted under with bricks, is reconstructed as a barrel vault and perhaps also if a large opening on the western face is assumed.

The age of the palace cannot be determined with the help of archeology. From the description from 1595 it is clear that there were no internal staircases even then. It can therefore be assumed that it had a relatively ancient architectural style, i.e. that it probably came from the time the castle was built in the late 12th / early 13th century. The lining of the cellar entrance is interspersed with bricks. So it was probably added later.

According to the drawing from 1688, there was a second, square tower roughly opposite the eastern tower, which had been saddled onto the curtain wall. If the representation is correct, this tower should be found south of the Palas. However, there is a suspicion that the drawing may be inaccurate. The apparent second tower would then be nothing but the hall itself. A residential tower at this point would be completely superfluous. The hall offers enough living space. In addition, a wall tower that has a stronger fortification than the east tower would be pointless at this point. This side is protected by Ahse and marsh meadows; an enemy was not to be expected from this direction. It is therefore more likely that the palace or the remainder of the palace that was still in existence at the time was not shown on the map with the necessary accuracy.

According to the map from 1751, the east tower was about 12 m long and 9.5 m wide. These dimensions can only be combined with the discovery of an excavation pit at the appropriate point if one assumes that the east tower was located further within the wall ring than indicated on the drawing from 1751. According to the map from 1688, access to the castle is south of the tower through the curtain wall. A comparison example with the castle of Rheda shows that this arrangement could have been created later. The east tower was then probably the original gate tower.

Lobbedey has succeeded in capturing the essential elements of the main castle with the curtain wall, gate tower and hall. Neither the written records nor the finds tell of other buildings. For a residential castle, the development was therefore relatively sparse. However, this should be seen in connection with extensive development in the outer bailey. The sources from the 16th - 18th centuries can of course no longer give a real impression of this, as the farm buildings were largely made of wood and were burned down or otherwise destroyed in earlier centuries. It is also conceivable that there were smaller buildings on the main castle that could not be recorded due to the limitation of the excavation areas or because of the profound disturbances. There is nothing to prevent the assumption that the main buildings date from the time the castle was built; However, this assumption is not archaeologically proven with certainty. A number of modifications were made later.

The following considerations can be made about this: The castle was probably built in one go and immediately expanded in stone. The scope of the archaeological investigations is not sufficient to rule out a previous building in the same place with complete certainty. However, the height of the mound is relatively low, even in direct comparison to smaller moths. A previous building should have been recorded. The broken fragments show that the main castle was actually used in the 13th to 15th centuries. Lobbedey was unable to secure older fragments. Thus the assumption is best justified that the castle was built shortly after 1198 by Friedrich von Altena or his son Adolf I. von der Mark in one go. Lobbedey has not found an Oberhof Mark or a castle belonging to Rabodo. If they did exist, they could have been elsewhere. It is also noteworthy that the main castle differs from the usual type of smaller, but often higher mounds due to its large area, and also by the fact that instead of the usual, central tower, which was at the same time residential and defensive construction, these functions on a circular wall, Gate tower and hall are distributed.

Comparative examples can hardly be used as these early castles were either destroyed or extensively rebuilt. The Rhenish moths Nörvenich and perhaps Heinsberg were of a comparable size . The moth in Leiden in the Netherlands has a circular wall of similar diameter. Excavations have revealed the existence of a gate tower there, but no further internal buildings. Rheda Castle is probably most closely related to Mark Castle. It is located on an artificial hill that is slightly larger in size and has an irregular oval shape. Rheda Castle is built in the Ems valley and, like Mark Castle, can only be reached via a dam. The shape and size of the outer bailey are also comparable to Haus Mark. The oldest surviving component is the gate tower with a well-known double chapel from the third decade of the 13th century. The battlements on the level of the chapel show that there was a circular wall. Images show that the castle had a mighty, roughly square residential tower, the so-called Templar Tower. Like the east tower of Mark Castle, this was also on the periphery of the castle hill. It was canceled after 1718. The expansion of Rheda Castle in this form is dated to the first half of the 13th century.

Finds

Individual finds from the main castle

The excavations have not produced any really valuable finds, as the castle was abandoned as planned and has gradually crumbled. In the excavation pits of the masonry and the dug up layers, medieval finds were discovered alongside modern material. This makes it difficult to establish an exact chronology.

The remains of clay pots were mainly found in the graves . Mostly it was local pottery (gray ceramic). To a lesser extent, imports from the Rhineland were also represented, fast stoneware and Siegburg stoneware from the 13th to 15th centuries. Among them was characteristic Siegburg stoneware from the 13th century in the form of shards of stoneware-like hard-fired goods, gray with a brown clay glaze . However, Siegburg stoneware from the 14th and 15th centuries was also discovered. In addition, there were jugs (including a piece of the rim), a corrugated base, stand knobs and bowls.

Glazed and painted earthenware and modern stoneware originate from a later phase of use of the moth in the 16th century. Most of the finds, however, date from the time of horticultural use and the demolition work in the 17th to 19th centuries.

A wooden bowl and two fragments of a trough or hand mill that was used to produce flour could also be recovered from the graves.

There were no finds in the filling, with the exception of a single edge fragment. The 12th century piece is not very characteristic; it could have got here secondary in the filler material.

A disc pommel sword from the 13th and 14th centuries belongs to the old inventory of the Gustav Lübcke Museum. It may come from Burg Mark.

A bronze spur from the 13th century must have belonged to a knight. The spur certifies the wealth and position of the castle residents; most of the spores were made of iron.

A heavily corroded iron spur comes from the early days of the plant. The find comes from the outer foot of the curtain wall in the soil discharge.

Gun finds are typical for castles. These include an iron arrowhead and the iron tip of a crossbow bolt. The arrowhead and the heavier point of the crossbow bolt as well as a fitting of a box and large wrought iron nails with a broad head are to be regarded as medieval.

A small fragment in the shape of a three-leaved crab is made of whitish sandstone. The approach is designed like a handle. This and the small size of the piece suggest less of an architectural fragment than of an object of daily use like a mortar.

The fragment of a sundial, made without great skill, is made of slate. The character of the digits allows them to be dated to the 16th or 17th century. Finally, the remains of the building material that were found in the excavation pits should be mentioned: light, yellowish or brownish sandstone, light gray limestone and green marlstone from the hair strand. Two architectural fragments are also made from this material, possibly from the first phase of the castle's construction. It is a piece of a window mullion and two matching fragments of a garment. This fragment is reddened by fire on part of the old surface.

Red and yellow bricks can be assigned to the more recent construction periods and repair work. Slate and hollow tiles ( monk and nun ) were found as roofing features .

An oak beam, which was recovered from the infill of the moat, presumably comes from a bridge construction. Its cross-section is 30 × 43 cm, its length 160 cm. On the narrow side, a 7 cm deep recess can be seen to accommodate an obliquely overlapping wood.

However, no statements can be made about the (interior) equipment of the buildings. Only part of the window mullion and part of a sandstone drapery are preserved. Brick is obviously one of the building materials used. This can also be found on other castles (such as the Isenburg) from 1200 onwards. The buildings were covered with tiles and slate.

Most of the finds date between 1200 and 1300. This confirms the assumption that the castle was mainly used in the 13th century.

The size of the castle and the bronze spur are consistent proof of the importance of the Counts of the Mark.

The bridge to the main castle

In September 1975, as part of the redesign of the facilities, the moats were dredged and the filled-in part of the moats between the main and outer bailey was restored. In the area where the bridge was suspected, the excavator encountered a large number of driven piles, some of which were located under the floor of a modern cellar. Thanks to municipal emergency services and volunteers, the findings were uncovered and measured.

When the investigation began, the remainder of a bridge pillar was discovered on the eastern edge of the new moat, which is narrower than the original. He rested on a beam grate, which consisted of 23 cm wide and 21 or 15 cm thick oak beams, which were linked together by cross beams in a carpenter-friendly manner. Under and between these beams were round piles about 80 cm in length, as well as split piles driven vertically into the ground. The width of the pile grid was 1.36 m, the length of the piece that was preserved was 1.70 m. Driving piles were found in the ground up to 2.80 m north of the demolition edge; the length can therefore be up to 4.60 m. Unprocessed rubble stones had been packed between the grating. The quarry stone masonry above, made of green marl stones, was connected by very hard, lime-rich, probably hydraulic mortar. The upper part of the masonry, which was probably above the water level, was built with ocher-colored, sandy mortar. At the base, the masonry was 1.20 m wide and tapered towards the top.

The pile grid of the pillar was already set in the existing, up to 40 cm thick mud deposits of the moats. So it cannot belong to the original system.

The tightly packed driven piles cannot all come from the same time either. All the piles, with one exception, were driven vertically. These were sharpened oak planks with a roughly square cross-section and a diameter of 20 to 35 cm (mostly around 25-30 cm). The majority of the piles are in two rows that are 2.50 m apart, which must have been the width of the bridge. The roadway leads directly to the gate tower, but not exactly in the middle, if the reconstruction of the tower can be accurate in this detail.

To the north of the bridge, two further pairs of piles were measured at a distance of about 1 m from each other. They could belong to a footbridge that led past the tower to the main castle. Such a footbridge is shown on the map from 1688, but south of the tower. It is uncertain whether this is due to a mistake in the drawing or to another fact that has not been archaeologically determined.

The mud deposits of the moats did not reveal any medieval stratigraphy in the area of the bridge, with the exception mentioned, the overlay by the pillar. Also in the lowest layers were, in addition to the medieval ceramic remains, more modern goods from the 16th and 17th centuries. According to this, the moat was desludged by the end of the Middle Ages.

Individual finds from the bridge area

Among the few ceramic finds, the bottom part of a glazed medieval jug is particularly noteworthy, as glazed pottery from this period is rare in this room. The hard-fired sherd, with fine sand, is dark blue-gray in the break, yellowish light gray on the inside, but light gray on the outside and covered with light green glaze. The vessel was made on the turntable and was without a doubt imported. It could be from the 13th or 14th century.

The fragment of a turned wooden bowl will also belong to this period. The inside is roughly worked and not smoothed. The piece may not have been completed.

Among the metal finds is an engraved late Gothic tin plate.

A lead weight in the form of a truncated pyramid with rounded corners and an eyelet at the top cannot be dated. It weighs 118.5 g, which is roughly half the weight of the mark (one mark in Cologne = 8 ounces = 233.779 g).

In addition, some iron objects (door cocks, boat hooks) were recovered, including part of a chain that was in the flooded hole of a drawn pile.

Finds in the outer bailey

A few meters to the east of the bridge, a well made of rubble stones with a diameter of 1.13 m was found. Its upper part was built with newer bricks; A large, round sandstone plate served as a lid. This fountain was obviously still in use in the 19th century. But its origin could still be in the Middle Ages.

In the south-west corner of the outer bailey, a finding was cut while laying an electric cable, which was then examined further in a further small exploratory incision. It was found that it is a stake group. There are three 20 to 24 cm thick oak posts that were rammed into the natural, sandy soil. The subsoil was at a depth of about 57.60 m above sea level, i.e. roughly at the level of the bottom of the main castle. Due to the action of organic substances, the sandy soil was colored greenish-blue and covered by a 40 cm thick, peaty layer. Numerous remains of leaves and twigs could be seen in this area. Thanks to this finding, there is no doubt that the piles originally stood in the moat of the outer bailey. Horizontally and slightly obliquely downwards, several remains of beams lay on the peat layer. T. were marked by strong traces of fire. They must have been caused by a fallen or burned beam above the driven piles. The diameter of the piles is less than that of most of the main bridge piles. Therefore, the construction can only have been a smaller bar. The findings are not sufficient to decide whether he has crossed the moat as a bridge. It would also be conceivable that it only led a little way into the moat and served daily business operations, possibly for washing dishes. The discovery of large quantities of broken glass indicates such a function. Some of the vessels were found in numerous juxtaposed shards. Above the horizon of the remains of the beam was another layer of loamy, dark-gray grave mud, about 40 cm thick and a bit more sandy. The two muddy fillings were covered by a 20 cm thick layer of yellow clay that contained a lot of charcoal and T. was reddened by fire. In the same stratigraphic situation as this layer, there was an up to one meter thick bed of rubble stones (green marlstone) with sandy loam in a limited area. With some certainty it is the debris from buildings, which is partly made of stone and partly of clay framework and has been poured into the moats. Further filling soil was deposited on top in two distinct layers.

Above all from the two lower, peaty and muddy fillings of the graves, but also from all other layers, rich ceramic finds could be recovered. Modern ceramics come from the top, humus-rich filling layer. Siegburg stoneware from the 14th century, including a cup, a large jug and a small jug, was found in the lower layer of the filling floor, i.e. still above the overburden layer. Fire and demolition of the outer bailey building (s) must have taken place beforehand. Indeed, the ceramic finds from the two layers of the Gräftenschlamm and the stone and fire rubble layers are noticeably older. No differences can be seen, but there is one exception: only in the bottom layer on the sole of the valley were shards of stoneware-like hard-fired goods in dark gray or yellow and a purple-brown or olive-gray surface. They belonged to jugs with an egg-shaped belly, a cylindrical neck, a wavy base and a collar rim; Siegburg stoneware from the middle of the second half of the 13th century. At the same time, a slightly different form of stoneware belongs: the shard is gray when broken, light brown or olive-gray on the surface, sometimes with spots of reddish-brown glaze. Small and large jugs with a cylindrical neck decorated with fine rotating grooves and a simply tapering, unprofiled rim and a wave base were found. The vessel wall is either short and bulbous or elongated in an ovoid shape. The upper part of the vessel wall is partially enlivened by ridges.

Earthenware has also been imported. This is evidenced by two shards of yellow-toned, hard-burnt earthenware, which are covered on the inside and outside by a red-brown engobe (clay coating). They belong to a type of goods possibly manufactured in Siegburg in the late 13th and 14th centuries.

The Siegburger imported ceramics are numerically outweighed by the ball pot ceramics. It occurs almost uniformly in the mud layers of the outer bailey site. All shards are thin-walled and hard-burnt, with fine-grained sand grain and gray and porous breakage. Their surface is usually black-gray, inside and sometimes also outside light gray. The body of the vessel is built up entirely by hand, only the edge is often turned. The following vessel shapes occur: spherical pots, the most widely used vessel shape, e.g. T. in considerable dimensions, a small tripod pot with stiletto handle (Grapen) and individual feet of other tripod vessels.

The neck zone is usually not particularly pronounced in the ball pots; occasionally it is decorated with thin grooves. Only in one case does it appear grooved and strongly set off and grooved, which is remarkable because the broadening of this feature obviously expresses regional differentiation. In North German and East Westphalian ceramics, the elongated neck zone with strong grooves is characteristic of the spherical pots of the 13th century, but not in Rhenish ceramics.

There were also fragments of vessels with a wave base and a squat, egg-shaped belly. These have been reconstructed as wide-mouthed jugs with handles. With some spouts and handles it could not be decided whether they belong to the category of spherical pots, tripod pots or vessels with a corrugated base. Another common type of vessel is the bowl. A larger fragment has standing knobs and a knob-like handle. A triplet vessel is a special form of three interconnected spherical pots with feet and a handle; part of the vessel is missing.

The Siegburg ceramics can be dated more easily and thus secures the dating for the handmade ball pot ceramics; both types of pottery have ever been found together. The Siegburg ceramics of the two lower muddy layers and the overburden layer belong to the period from the middle to the end of the 13th century. The gray pot ceramic is also very uniform. Therefore, both types of goods must be assigned to the same period. The uniformity of the pottery also suggests that it is essentially the product of a single pottery, probably located in the vicinity of the castle. A fish frying pan with a brownish-green glaze on the inside may also come from this pottery , which is indicated by its identical clay texture.

Other finds from the same layer context are: shoe leather, large amounts of animal bones, parts of the bridle and an almost complete, tongue-shaped roof slate plate with three original nail holes and an inner fourth from a repair, as well as two fragments of a sandstone hand mill. It is a fragment from the edge of the bottom stone and half of the runner stone. Its top is chipped. A similar hand mill was found in the Altenberg mining desert near Müsen in the Siegen-Wittgenstein district . It also seems to date from the 13th century. A fragment from the floor stone of another, even larger mill was picked up in the excavation.

Overall, the finds from the moats of the outer bailey are likely to be of particular interest as they are approximately contemporary and dated material from the first phase of use of House Mark in the 13th century.

Individual evidence

- ↑ ( page no longer available , search in web archives: ground monument Burg Mark )

- ↑ Josef Lappe, Hamm in the Middle Ages and in the Modern Age, The Burg zur Mark in: 700 Years of the City of Hamm, Festschrift to commemorate the 700th anniversary of the city , Werl 1973

- ↑ a b The Burgraves of Stromberg

- ^ Pickertsche Sammlung ( Memento of October 3, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d e f Reinhold Stirnberg: Before the Märker came . In: Active Seniors, Magazin für Schwerte, No. 59, pp. 10–18, 2002 (PDF; 990 kB)

- ^ Johann Suibert Seibertz : Diplomatic family history of the dynasts and lords in the Duchy of Westphalia . Arnsberg 1855. pp. 192ff.

- ↑ a b Willi E. Schroeder: A home book. Two districts introduce themselves. Bockum and Hövel. 1980.

- ↑ Christoph Jacob Kremer History of the Counts of Berg.

- ↑ Ingrid Bauert-Keertman, Norbert Kattenborn, Liesedore Langhammer, Willy Timm, Herbert Zink, Hamm. Chronicle of a City, Cologne 1965.

- ^ The regests of the Archbishops of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Vol. 2. Edited by R. Knipping. Bonn 1901, No. 1103 and 1219.

- ↑ Josef Lappe, Hamm in the Middle Ages and in the Modern Era, Die Burg zur Mark in: 700 Years of the City of Hamm, Festschrift to commemorate the 700th anniversary of the city , Werl 1973, p. 52.

- ^ House Opherdicke

- ↑ a b The Homburg and the Mark Castle, district-free city of Hamm . Published by the Regional Association of Westphalia-Lippe as the font Early Castles in Westphalia 19 in 1979

- ↑ http://www.bochumer-maiabendgesellschaft.de/a-z1.htm

- ↑ Magistrate of the City of Hamm (Westphalia) (Hrsg.): 700 years city of Hamm (Westphalia). Festschrift to commemorate the 700th anniversary of the city of Hamm (Westphalia). Stein, Werl 1973 (unmodified reprint of the original edition from 1927), ISBN 3-920980-08-5

- ^ WF Prins, The Counts of the Mark and their Descendants , in: The Counts of Limburg Stirum, Part 1, Vol. 1, Münster 1976.

- ^ Harm Klueting, History of Westphalia: the land between the Rhine and Weser from the 8th to the 20th century , Paderborn 1998, ISBN 3-89710-050-9 .

- ↑ Ingrid Bauert-Keertman, Norbert Kattenborn, Liesedore Langhammer, Willy Timm, Herbert Zink, Hamm. Chronicle of a City, Cologne 1965, p. 29.

- ↑ Referring to a comment by Flebbe on Levold from Northof's Chronicle of the Counts of the Mark from 1955.

- ^ So Flebbe in a note on Levold von Northof, Chronicle of the Counts of the Mark.

- ^ Möller, Historical-Genealogical-Statistical History of the capital Hamm and the original development of the Grafschaft Mark, together with some corrections , reprint of the Hamm 1803 edition, Osnabrück 1875.

- ↑ History of Altena Castle (PDF; 84 kB)

- ^ Friedrich von Berg-Altena at genealogie-mittelalter.de

- ↑ a b c d e Uwe Lobbedey: On the building history of House Mark. The excavation on the motte in 1973 , in: Herbert Zink (Ed.): 750 years city of Hamm, Hamm 1976, pp. 39-68.

- ^ Eggenstein, in: Georg Eggenstein, Ellen Schwinzer, Zeitspuren. The beginnings of the city of Hamm , Hamm 2002, p. 79.

- ↑ Josef Lappe, Hamm in the Middle Ages and in the Modern Age, The Burg zur Mark in: 700 Years of the City of Hamm, Festschrift to commemorate the 700th anniversary of the city , Werl 1973.

- ↑ Weber, Graf Adolf I. von der Mark , in: Yearbook of the Association for Orts- und Heimatkunde in the Grafschaft Mark 35, Witten 1922, pp. 1-68, pp. 45f.

- ^ Johann Diederich von Steinen, Westphälische Geschichte, part 4, Lemgo 1760 (reprint: Münster 1964), p. 562.

- ^ Homepage of the "Burg Mark" Hamm eV association

- ↑ Contribution to the friends' association “Burg Mark” Hamm eV in Hammer local television HammTV.

- ↑ Report by the Westphalian Gazette of May 2, 2010.

- ^ Reporting by the Westphalian Gazette on July 9, 2010.

- ↑ Report on local television HammTV of 24 August of 2010.

- ↑ Reporting in Hammer local television HammTV from October 28, 2010.

literature

- Antiquities Commission for Westphalia (ed.): The Homburg and the Mark Castle, district-free city of Hamm , Münster 2002 (= early castles in Westphalia 19).