Busman band

The Busmann Chapel was a side chapel of the Sophienkirche in Dresden , which was added around 1400. At that time the Sophienkirche was still part of the Dresden Franciscan Monastery . The rich patrician Busmann family donated the extension as a family and funeral chapel. The sculptural decoration of the chapel was the earliest documented in Dresden. The busts of the donors on console stones are the first surviving pictorial representations of Dresden citizens.

The Busmannkapelle, like the church , was destroyed in the bombing of Dresden in February 1945. Since 1994 there have been plans to reconstruct the chapel in a modern form at its original location and to use it as a memorial to the destroyed Sophienkirche. The first construction work for the Busmann Chapel Memorial began in 2009.

The Busmann family

The Busmann band was donated by the Busmann family and named after them. The Busmann family was one of the most important and exceptionally wealthy patrician families in Dresden in the 14th and 15th centuries. Lorenz Busmann's name appears for the first time in a document in 1362; here he is referred to as an "honorable man". Busmann joined the city council in 1387 and was mayor of Dresden four times (1392, 1400, 1403, 1406) . He died in 1406 or early 1407. Lorenz Busmann lived in a house on Webergasse until his death and left five sons. He and his wife donated the chapel.

Another Lorenz Busmann died in 1440 and found his final resting place in the Busmann Chapel. Johannes Busmann's wife, Elisabeth, who died in 1478, was also buried in the chapel. Other well-known family members are Heinrich Busmann, who followed Duke Albrecht to the promised land in 1476 and died on the trip, as well as Martin Busmann, who still supported the Franciscan monastery in 1486.

history

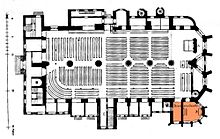

As early as 1351 a new monastery church was built for the Franciscan monastery in Dresden, which was first mentioned in 1272 . In the south choir of the two-aisled hall church , an unknown master builder probably created the so-called Busmann Chapel between 1398 and 1406. It served the Busmann family as a chapel and burial place. Until 1552 the chapel had an altar with a representation of the Holy Sepulcher .

After the Reformation , the monastery was profaned and used, among other things, as an armory and storage facility for food. After the Sophienkirche was consecrated again as a place of worship , the chapel was set up as an entrance hall around 1600. Around 1720 the Sophienkirche received a new Silbermann organ , which found its place in the gallery above the south choir. During this time, a ceiling was put in halfway up the windows of the Busmann Chapel and the upper room was used as a bellows chamber for the organ.

Probably as early as 1720, but certainly from 1737, the chapel served the court preacher as a sacristy - the Sophienkirche received the status of a Protestant court church in 1737. From September 17, 1737, private communions were held in the chapel . For this she was given access through the south wall of the Sophienkirche. From the castle chapel , which was dissolved in 1737 , the Busmann Chapel received the altar from Wolf Caspar von Klengel and a baptismal font from Hans Walther II .

It is controversial whether the chapel was actually divided with a wall from 1737 to 1864, as can be seen in a floor plan before 1864: "In the baroque floor plans, this partition is provided and according to the plans of Cornelius Gurlitt it was also drawn in". In contrast, the partition wall is not mentioned in contemporary literature.

As early as 1824 the chapel was repainted and provided with stucco in the neo-Gothic style . In 1864 the great renovation of the Sophienkirche took place under Christian Friedrich Arnold . The chapel received tracery windows and the organ of the Sophienkirche got its new place on the north west gallery, so that the ceiling of the chapel, which was drawn in in 1737, could be removed. The busmann band was now one-room again. On the west wall, a gallery was built on the posts of the bellows chamber, which was accessible "from a staircase leading to the gallery in the side corridor". At the same time the entrance to the chapel was relocated. While direct access from the outside was previously possible, the chapel could now only be entered via the widened entrance from 1737 in the south wall and an entrance from the newly created corridors of the side aisle from 1864. The wooden floor of the chapel was replaced by stone slabs and the chapel was repainted. In 1875, Arnold improved the vault and added tracery and jambs of the windows. From 1875 to 1910 the Nosseni epitaph was placed in the chapel .

During the renovation of the Sophienkirche in 1910, a new two-room crypt was created under the Busmann Chapel , which replaced the old crypt of the church under the altar area. Crypts were found at a depth of 4.5 meters in which, in addition to remains of bones, women's costumes from the 15th century and the costumes of the Franciscans had been preserved. Since only members of the Busmann family found their final resting place in the chapel, the clothes found can be assigned to the Busmann family. The burial of male family members in the costume of the Minorites shows that numerous members of the family were closely associated with the monastery as lay brothers. The new crypt was designed by Hans Erlwein and painted by Paul Rößler . It was only accessible from the Busmann Chapel and contained, among other things, the artistic coffins of the Wettins .

In February 1945 the Busmann band burned down like the rest of the church. The vaults collapsed in 1946. Some architectural fragments of the chapel were salvaged before the Busmann Chapel, like the rest of the church, was demolished from 1962 to 1963.

Room description

The bus man's band was a high, five meters wide and eight meters long room. It had a six-part star vault that was created when the church was vaulted in the second half of the 15th century. "The network of the vault is particularly original to the east, finely structured and provided with small round keystones at the intersections". The interior of the chapel was decorated with stucco in the neo-Gothic style.

In the east there was a small choir made up of an irregular octagon. "Six buttresses counteracted the thrust of the vault, which was covered with a hipped gable roof ." Between the pillars were five high pointed arched windows .

In the corners of the choir there were rounds of services that divided the walls and developed from the fillets of the window frames. The ribs of the vault, in turn, emanated from the circular services. Designed console stones were attached halfway up the services. The console busts of Mayor Lorenz Busmann and his wife flanked the altar placed in front of the second window from the east. In front of the altar chairs were set up in several rows with the baptismal font in the middle.

On the west side of the chapel, halfway up the window, there were "four very peculiar ... pillars imitating a wooden construction in stone", the posts of the former bellows chamber floor. The supports were used around 1864 for a built-in balcony-like gallery , which carried a balustrade with Gothic tracery.

In 1824 the slug panes in the chapel were replaced by wider window panes. During the renovation under Arnold in 1864, the chapel received tracery windows , with four windows having two lanes and the southernmost three-lane. Although the tracery was repaired in 1875, Cornelius Gurlitt noted as early as 1900 that the tracery windows were no longer preserved.

The entrance to the chapel was through an arched portal in the southwest of the chapel, above which there was a small window. During the renovations from 1864, the portal was walled up. Since then, access to the chapel has been via a large passage from the nave and a smaller one from the aisle-like corridors created in 1864.

Furnishing

The sculptural decoration of the chapel is the earliest that has been recorded in Dresden. It can be proven that it was the altar with the depiction of the Holy Sepulcher, which was located in the chapel until 1552, the figure of a kneeling woman and variously designed console stones. While the altar and the female figure were destroyed in 1945, four console stones have been preserved. Fritz Löffler described the altar and the console busts as "the earliest sculptures of importance that Dresden has to show". Other furnishings, such as a successor altar and the baptismal font, came from the old castle chapel .

altar

Altar with the Holy Sepulcher

The age and the artist of the first altar in the Busmannkapelle are unknown. The time of origin is estimated at the beginning of the 15th century. While Albert von Eye suspected an echo of the older Saxon sculpture in the sculpture group, Gurlitt saw a parallel to the Swabian-Bohemian school and an inner relationship with the Holy Sepulcher in Schwäbisch Gmünd from 1410 as given.

After the secularization of the Franciscan monastery and thus the church, the altar passed from the Busmann Chapel into the possession of the Bartholomew Hospital in 1552 and was installed in the Hospital Church of St. Bartholomew . When the hospital was demolished in 1839, the piece came into the possession of the Royal Saxon Antiquities Association , which stored it in the palace in the Great Garden . Here the altar, of which only parts had been preserved around 1900 , was destroyed in the bombing of Dresden in February 1945.

The altar was made of sandstone and consisted of an altar table with the representation of the Holy Sepulcher on a base plate and a top. Without the top, the altar table was 105 centimeters high, 173 centimeters wide and 126 centimeters deep.

Holy grave

Four rectangular pillars carried a heavily profiled plate, which had a pointed round arch frieze on the lower profile. The bows had noses and ended in lilies . The actual tumba on which Jesus lay was adorned with a tracery frieze. A total of four guards stood between the stone pillars on the narrow sides and in front of the grave.

The body of Jesus was 118 centimeters long. His head - the face with sunken cheeks and closed eyes - was on a pillow and his hands were crossed on his torso. The only clothing of the figure was a loincloth . Gurlitt described the Jesus figure as one of the “most noble creations of German sculpture”. The figure was partly colored, so the curls of Jesus were painted black and the chest wound still showed traces of red paint around 1900.

Behind Jesus were three depictions of women 63 centimeters high, wearing headscarves and wide cloaks. All three held ointment cans in their hands. At the head and at the feet of the Jesus figure stood on the narrow sides an angel with long wings, who waved a censer.

A kneeling female figure that was preserved until 1945 and was 72 centimeters high may also have belonged to the grave. Gurlitt saw in her a donor figure who was originally placed to the left of the grave and whose male counterpart had been lost around 1900. Otto Wanckel referred to her as a Magdalene figure who belonged to a crucifixion group above the Holy Sepulcher; an interpretation that Fritz Löffler called "the more likely".

Predella

The 35 centimeter high predella of the altarpiece on it was also preserved around 1900 and had the coat of arms of the Busmann family on the side. The predella was painted with tempera and showed a figure of the Savior and six apostles on each side. The figures had disproportionately large heads and awkwardly oval halos, so that the work was classified as the work of a "craft artist". The shrine above it around 1900 did not belong to the original altar, but, according to Gurlitt, possibly came from the Dreikönigskirche .

Altar of the palace chapel

In 1737 and 1738 the Busmann Chapel received the altar of the secularized palace chapel. It dates from 1662 and "is undoubtedly the work of the chief architect Wolf Caspar Klengel ". In 1659 Klengel had examined which Saxon gemstones were still available and which marble quarries were still productive. The efforts of Elector Friedrich August I to use more native stones were evident on the altar, the main decoration of which was various Saxon types of stone. The four column shafts made of green rock were an exception. According to legend, they were carved from a block of marble that Duke Albrecht had brought to Saxony from the Holy Land in 1476 and that was given to him there as a remnant of the temple in Jerusalem .

The altar table had a top of red marble with white veins, supported by heavy pilasters made of black marble. Between the pilasters was an arch architecture made of serpentine and fields of red marble.

The altarpiece had two pillars on each pedestal made of red stone. Its base was made of red limestone, an intermediate link decorated with foliage made of alabaster from Weissensee and the 97 centimeter high shafts made of green, possibly Jerusalem breccia . Above it were composite capitals , which were also made from Weißensee alabaster. A heavily cranked entablature made of Crottendorfer marble closed the altar in a round arch. Between the pillars was a simple, empty plate made of red stone, in front of which a crucifix later stood.

After the bombing of Dresden, the altar was already measured after the end of the war in 1945 and the structure of the altar, presumably largely undamaged at the time, was recovered. The altar table and cafeteria remained in the bus man's chapel, where they were severely damaged when the vaults collapsed. They are no longer preserved today. The crucifix was recovered, but its current location is unknown.

The altar structure was probably damaged when it was moved. His remains are currently stored in the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments in Saxony. In addition to the four columns, the intermediate links and composite capitals made of alabaster, large parts of the cranked entablature and individual end and connection plates have been preserved. The pedestals and the plate between the columns have not been preserved. It is believed that, contrary to what Cornelius Gurlitt said, it was not made of red marble. On the one hand, the surface of the plate would have been unusually large. On the other hand, the missing remains, in contrast to the otherwise largely preserved structure, suggest that the slab was only bricked and plastered or a marbling was painted on . The altar is to be reconstructed on the basis of the measurements made in 1945 and then installed in the new castle chapel that is currently being built.

Baptismal font

In 1737 the Busmannkapelle received the baptismal font of the castle chapel, which was secularized in the same year. It was a sandstone work by Hans Walther II from 1558. The baptismal font was decorated with colored stones, including jasper , various types of marble and serpentine , in 1602 , and it was possible that it was only at that time that the column decoration on the chalice was given. The baptismal font is said to have been changed again in 1606. It was badly damaged in the bombing of Dresden in February 1945. The reconstruction of the baptismal font from numerous preserved fragments took place in 1988 and 1989 by the Dresden sculptor's workshop Hempel and the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments in Saxony . The fragmentary baptismal font is now in the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments of Saxony in Dresden.

The font is 115 centimeters high and has a maximum diameter of 88 centimeters. The base is divided by four pilasters connected by arches. In the arches there are putti in mourning clothes. The belly of the chalice-like baptismal font is divided into four double hermen , between which there are flower garlands with putti and birds. Above it is a continuous row of diamond blocks in different types of marble.

The chalice is divided four times by two Ionic columns, between which there were both serpentine niches and four gilded alabaster reliefs . They showed the flood with Noah's ark , the walk through the Red Sea , the baptism of Jesus and the blessing of children . While the baptismal font is made of red marble, the baptismal lid was decorated with lions' grimaces , tendrils and a meandering edge made of wood. The baptismal lid, which had the resting lamb of God as a gilded end , has not been preserved. Gurlitt saw the foot, relief and baptismal lid as Walther's work, while he classified the other parts as additions from the period after 1600.

Console stones

The console-like structural members were in the corners of the choir. They protruded into the room halfway up the window. Gurlitt suggested that the consoles originally carried statues. The console stones had a different design. They were designed as the upper body of a woman, a man, a winged person, foliage and an eagle. Robert Bruck suspected in 1912 that further console stones were attached to empty choir corners around 1900. Analogous to the eagle (symbol of the apostle John ) and the human being (symbol of Matthew ), Bruck assumed that the missing stones represented a lion (symbol for Mark ) and a bull (symbol for Luke ). These were possibly knocked off with the services when the wall to the nave broke through around 1701. Bruck also mentioned another seven console stones that were found during excavations around 1910: four showed foliage, one a head with foliage, one a pelican with its young and another a representation of animals. None of these seven stones has survived.

The stone of the eagle was still there around 1912 but was lost. Four console stones have been preserved: two busts and the console with the winged person made of fine-grain (labiatus) sandstone, which were recovered in 1945, and the foliage console made of coarse-grained Elbe sandstone , which was only recovered in the 1960s when the chapel was demolished. All four came to the Dresden City Museum , where restorers freed them from overpainting and examined them. A total of eight different layers of paint were found, including three layers of gray in lime color .

Of particular importance are the console busts of the man and the woman, which "represent creations that are noteworthy for medieval sculpture in Dresden, since they clearly show that the artist created portraits". They are also the earliest surviving portraits of Dresden citizens. The bust of the man bears the house brand of the Busmann family, so that it is certain that the portrayed are the donor Lorenz Busmann and his wife, whose name is unknown.

Fritz Löffler saw similarities in the busts with works from the Parler School, such as the bust of Matthias von Arras or the head of the tumba Ottokar II. Přemysl , and described them as the “most precious figural work” of the chapel.

Busmann Chapel Memorial

The Dresden city council decided in 1994 that a memorial should be built for the Sophienkirche. A basic requirement of the tender was that preserved architectural fragments of the Busmann Chapel should be included in the design of the memorial. These included:

- 40 service workpieces

- 6 rib beginners

- 23 soffit arch pieces

- 1 sill piece

- 21 pieces of clothing

- Tracery remains of the windows from 1864

- 3 corbels (west gallery)

- 4 console stones (Mrs. Busmann, Lorenz Busmann, angel, foliage)

To protect the original pieces, they should be presented in a closed room and "with the site-specific presentation of the preserved architectural parts [...] the history of the Sophienkirche with the Busmann Chapel should be continued."

In the architectural competition advertised in 1995, a design by the Dresden architects Gustavs und Lungwitz, which provides for a spatial reproduction of the busmann's band at the original location, won out of twelve applications. The building sculpture should be enclosed in a glass showcase. “The buttresses of the Franciscan Church are erected as stylized steles to illustrate the connection between the Busmann Chapel and the Sophienkirche”, according to the design of the architects' office. The cost of the memorial is 2.6 million euros. The construction of the first four steles began on February 13, 2009.

literature

- Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912.

- Wiebke Fastenrath: To the former bus man band in Dresden . In: State Office for the Preservation of Monuments (ed.): Preservation of monuments in Saxony. Notices from the State Office for Monument Preservation Saxony . State Office for Monument Preservation, Dresden 1996, pp. 5–15.

- Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1. CC Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900 - full text in the offer of the SLUB

- Fritz Löffler: Console figures in the Busmann Chapel of the former Franciscan Church in Dresden . In: Journal of the German Association for Art History . Volume XXII, Issue 3/4, Berlin 1968, pp. 139–147.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Fritz Löffler: Console figures in the Busmann Chapel of the former Franciscan Church in Dresden . In: Journal of the German Association for Art History . Volume XXII, Issue 3/4, Berlin 1968, p. 139.

- ^ Wiebke Fastenrath: To the former Busmann band in Dresden . In: State Office for the Preservation of Monuments (ed.): Preservation of monuments in Saxony. Notices from the State Office for Monument Preservation Saxony . State Office for Monument Preservation, Dresden 1996, p. 5.

- ^ Wiebke Fastenrath: To the former Busmann band in Dresden . In: State Office for the Preservation of Monuments (ed.): Preservation of monuments in Saxony. Notices from the State Office for Monument Preservation Saxony . State Office for Monument Preservation, Dresden 1996, p. 10.

- ^ A b Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 23.

- ^ Wiebke Fastenrath: To the former Busmann band in Dresden . In: State Office for the Preservation of Monuments (ed.): Preservation of monuments in Saxony. Notices from the State Office for Monument Preservation Saxony . State Office for Monument Preservation, Dresden 1996, p. 15.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 35.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 7.

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1. CC Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900, pp. 81 and 85.

- ^ Wiebke Fastenrath: To the former Busmann band in Dresden . In: State Office for the Preservation of Monuments (ed.): Preservation of monuments in Saxony. Notices from the State Office for Monument Preservation Saxony . State Office for Monument Preservation, Dresden 1996, p. 7.

- ↑ a b c Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, part 1. CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, p. 81.

- ↑ a b Fritz Löffler: The old Dresden. History of his buildings . E. A. Seemann, Leipzig 1999, p. 23.

- ^ A b Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 9.

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1. CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ a b c d Fritz Löffler: Console figures in the Busmann Chapel of the former Franciscan Church in Dresden . In: Journal of the German Association for Art History . Volume XXII, Issue 3/4, Berlin 1968, p. 140.

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, part 1. CC Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900, p. 86.

- ↑ a b Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, part 1. CC Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900, p. 87.

- ↑ Otto Wanckel: Guide through the Museum of the Royal Saxon. Alterthumsverein in the Palais des Königl. Large garden in Dresden . Royal Saxon Antiquities Association, Dresden 1895, p. 118.

- ^ Anton Weck: The Chur-Princely Saxon widely-called Residentz- and Haupt-Vestung Dresden description and presentation . Froberger, Nuremberg 1679, p. 200.

- ↑ a b Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1. CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, p. 154.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 24.

- ↑ Lt. Gurlitt. Bruck called the clothing monk's robes. Cf. Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 23.

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1. CC Meinhold & Söhne, Dresden 1900, p. 152.

- ^ A b Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 8.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Fritz Löffler: Console figures in the Busmann Chapel of the former Franciscan Church in Dresden . In: Journal of the German Association for Art History . Volume XXII, Issue 3/4, Berlin 1968, p. 144.

- ^ Fritz Löffler: Console figures in the Busmann Chapel of the former Franciscan Church in Dresden . In: Journal of the German Association for Art History . Volume XXII, Issue 3/4, Berlin 1968, p. 145.

- ↑ List after Wiebke Fastenrath: To the former Busmannkapelle in Dresden . In: State Office for the Preservation of Monuments (ed.): Preservation of monuments in Saxony. Notices from the State Office for Monument Preservation Saxony . State Office for Monument Preservation, Dresden 1996, p. 11.

- ^ Wiebke Fastenrath: To the former Busmann band in Dresden . In: State Office for the Preservation of Monuments (ed.): Preservation of monuments in Saxony. Notices from the State Office for Monument Preservation Saxony . State Office for Monument Preservation, Dresden 1996, p. 11.

- ↑ Quoted from busmannkapelle.de

- ↑ Thilo Alexe: Remains of the Sophienkirchengruft discovered . In: Sächsische Zeitung, October 15, 2009, p. 15.

Coordinates: 51 ° 3 ′ 4.7 " N , 13 ° 44 ′ 5.7" E