Camber Castle

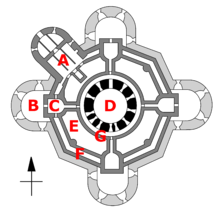

Camber Castle , formerly also called Winchelsea Castle , is a ruined castle near Rye in the English administrative division of East Sussex . King Henry VIII had the fortress built between 1512 and 1514 to protect the Sussex coast against feared French attacks. The first defensive structure on the site was a small, circular gun turret from which one could monitor the anchorage of Camber and the entrance to the port of Rye. In 1539, growing tensions with France led King Henry to reconsider his plans for coastal protection. In the following year Camber Castle was rebuilt and expanded under the direction of the Moravian engineer Stephan von Haschenperg . The result, however, was viewed as unsatisfactory, so in 1542 and 1543 further, very elaborate work was carried out to rectify the problems. The result was a large ring fortress with a central donjon , surrounded by four round bastions and an entrance bastion made of stones and bricks .

The completed castle was initially equipped with 28 bronze and iron cannons and a garrison of 28 men, who were commanded by a captain . The fortress may have been in full operation in 1545 when a French fleet attacked the English south coast, but its military use was short-lived. Camber's anchorage and the surrounding harbors began to boom and were no longer usable for shipping. The coastline shifted further seaward, so that the fort was soon far inland. In addition, the fortress was overtaken by newer military constructions in Europe before it was even completed, and a peace with France later in the 16th century reduced the need for coastal fortresses. The fortress was used until 1637 and then the order of King I. Charles closed. When the English Civil War broke out in 1642, it was largely razed by parliamentary troops so that the royalists could not use it.

The ruins became a popular picnic spot in the 18th and 19th centuries and were also painted by William Turner . Plans to convert the fortress into a Martello Tower or a clubhouse for the local golf club were not realized. The property was used during the Second World War , presumably as an advance warning post. Archaeological interest in the fort increased after the war and in 1967 it was placed under state protection. In 1977 the property was sold to private individuals. Today it is managed by English Heritage, and after an extensive conservation program, it is again open to the public between 1968 and 1994. The fortress is an unusual example of an unchanged Device Fort and is listed as a historical building of the first degree.

history

16th and 17th centuries

First tower, 1512–1514

Camber Castle was built about halfway between the ports of Rye and Winchelsea (about a mile from both ports) on the south coast of England and guarded a maritime area called The Camber at the mouths of the Brede , Rother and Tillingham rivers . The two cities were part of the Cinque Ports , a strategic chain of seaports responsible for providing ships for the royal navy, although Winchelsea's port was in ruins until the 16th century, which limited its usability, and the port of Rye soon faced similar problems. The Camber estuary was also affected in the late Middle Ages, even if this process had created an important new anchorage for ships.

The first attachment in Camber was probably shortly after 1486 by Sir Richard Guildford , the Master General of the Ordnance , built by King Henry VII. The basic rule Higham in Kent had received as payment for the construction of a defensive tower to protect the anchorage. However, there is no evidence that Guildford actually built such a tower to this day, and King Henry VII did not invest much in coastal protection until the end of his reign. Many castles across England were in bad shape at the time and were often considered outdated and too expensive to maintain.

Henry VIII was crowned king in 1509 and followed a more aggressive policy towards neighboring France than his father. Tensions increased in 1512 and Henry VIII ordered the construction of a gun turret and a new bridge in Camber. The work was carried out under the direction of Edward Guildford , Richard's son, at a cost of £ 1309 over the next two years. The resulting round stone tower was 20 meters in diameter and 9.1 meters high, filling the pebble strip of Kevill Point and controlling The Camber and Rye Harbor. This fortress probably only offered relatively limited facilities and living quarters and was probably not permanently occupied by a garrison.

Although it was a flat-topped gun turret to accommodate heavy cannons, the turret initially lacked artillery and was therefore unable to protect Rye from the enemy attacks from the sea that were carried out against the coast in the 1520s. After many letters that Guildford wrote to the Lord Chancellor , Cardinal Thomas Wolsey , around 1536 some cannons in the form of steel field snakes finally arrived. Premonitions of another colmation by The Camber that would eventually render it unusable as an anchorage surfaced in the mid-1530s.

Ringburg, 1539-1540

In 1539 the fear of an invasion by France and Spain grew and King Henry ordered the protection of the English coasts to be improved. A number of device forts were erected across England. They should carry cannons that could attack enemy ships when they approached the coast, preventing any enemy landing. As part of this work, Camber Castle was significantly upgraded at a cost of £ 5660.

The first phase of this work was carried out from 1539 to autumn 1540. the Moravian engineer Stefan von Haschenperg was responsible for the construction of the fort. He was very well paid for his work on this and other similar projects such as Calshot Castle , Hurst Castle , Sandgate Castle and Sandown Castle with an annual salary of £ 75. Philip Chute , John Fletcher and William Oxenbridge , all well-known local greats, served as commissioners for the project; Oxenbridge became the paymaster. Before the work was finished, more cannons were sent to Camber Castle and presumably installed in temporary batteries around the castle grounds.

Initially, the old tower was converted into a stronger keep that could carry cannons on its roof, and a gatehouse was added to it; four "Rührertürme" - so called because of their shape - and a curtain wall formed outside the castle and ramparts were built around the wall. Towards the end of this work phase, the castle went into an insane construction site, probably because of the pressure from the king himself. The curtain wall was raised, the gatehouse converted into an entrance bastion, a new network of underground passages installed and outer works added around the bastions. At the end of 1540 the castle was occupied by a garrison of 17 men and equipped with artillery. Chute was appointed captain.

The result was a ring fortress that von Haschenperg had hoped would combine the best of Italian architecture, be able to carry heavy cannons, but display a low profile that would protect it from enemy artillery fire. Various shortcomings soon became apparent. The fort's construction was defensive, which meant that the cannons could not be easily aimed at enemy ships, which was the original purpose of building a fort in Camber. The entrance structure to the fortress ensured that some areas of the lake were in the shade of fire, and the high water table probably caused serious problems with moisture on the ground floor. In addition, the construction of Camber Castle was different from that of other coastal fortresses across the region, considered unusual and contrary to the king's general intention to have a chain of forts built.

Revised ring castle, 1542–1543

Because of problems with the original construction, work on the castle began again in the summer of 1542, long after the initial fears of invasion had ended. They lasted until August 1543. The decision to fix the problems at the castle was probably made by King Henry himself. Oxenbridge seems to have continued to be paymaster and also took over the role of project manager, whereby von Haschenperg almost up to despite the difficulties with his earlier work remained in his role as civil engineer at the end of the project. The cost of this second phase was significantly higher than the first, around £ 10,000.

The construction differed significantly from that of Haschenberg's first castle. The donjon and the "stirrer towers" were raised and the level of the ceilings raised, the curtain wall reinforced, the old bastions completely removed and instead four new, larger bastions added, while the old outer works around the castle were demolished. The flat roof of the donjon was converted into a sloping roof and the cannons that supported it were relocated to the outer bastions. Although the castle had become a little smaller, the new construction offered much more living space for the garrison.

In practice, the new construction also ignored the trend towards acute-angled bastions that was prevalent in Europe; the round towers created large areas in the shadow of fire around the castle, into which the cannons could not fire; the high walls offered a greater target for enemy fire, the internal layout was complicated and it was difficult to move around the fort. Indeed, the historian Peter Harrington describes the final construction of the fortress as "more archaic than its predecessor". Chute's role was expanded to include custodian and captain of Camber Castle, custodian of the waters of Camber and puddler in January 1544, for which he received two shillings a day. Von Haschenperg left England in 1544 in disgrace and disgrace; he was faced with allegations that he was "a man who pretends to know more than he actually has".

Most of the building blocks required for the two phases of construction came from the dissolution of the Winchelsea monastery and the nearby Fairlight and Hastings quarries . Better quality stones were bought from Mersham in Hampshire and from various suppliers in Normandy . The wood came from Udimore , Appledore and Knell ; the latter two tree felling actions were carried out directly by the Camber Castle project team. Chalk was sourced from Dover to make lime , and at least 16,000 bricks were initially purchased to make the necessary furnaces ; probably over 500,000 more bricks were fired as the work on site progressed. Steel, iron and tiles were purchased locally in Sussex, along with 10 tonne cranes for the site's quay.

use

The castle was no longer needed when it was completed, as newer military constructions in Europe no longer used round bastions, but instead used pointed bastions, as in the later star-shaped forts. Nevertheless, Camber Castle was used as an artillery fort for the remainder of the century, from 1540 with a garrison of 24 men under the command of Chute and from 1542 a garrison of 28 men and a captain. Even if the castle was equipped with loopholes for handguns from the beginning , its weal and woe depended to a decisive extent on archers when attacked from the land side. 1568 were z. B. 140 longbows and 560 arrows stored there, presumably for the local militia in times of war. Polearms were stored in the castle in considerable quantities, also for the militia.

Initially the fort was armed with between 26 and 28 guns, e.g. B. bronze small cannons, field snakes , small field snakes and a falcon, as well as steel guns, z. B. Portpieces (large naval cannons) and "Bases" (large cannons). After 1568 the number of cannons was reduced to nine or ten for the rest of the century, e.g. B. cannons, small cannons, field snakes and small field snakes. Bronze cannons could fire faster, up to eight times an hour, and were safer to use than their iron counterparts. It is not known how far the fort's cannons could fire; Researchers in the 16th and 17th centuries stated that e.g. B. a field snake had a range of 1600-2743 meters.

In July 1545 the French raided nearby Seaford and so the castle could have been used in attacks against the French fleet. But soon Schlick began to block the entrance to The Camber , which prevented its use as an anchorage. In 1548 complaints were made about the situation to Parliament , and in 1573 the Rye authorities expressed concern that The Camber might be irreparably damaged. By the end of this century, exploiting the marshes and dropping ballast from passing ships had hastened this natural process and ruined the anchorage. The surrounding region also lost its strategic importance: cities like Winchelsea and Rye were on the decline, peace had been made with France in 1558 and military interest turned to the threat posed by the Spanish in south-west England.

From 1553 the castle was occupied by a garrison of 26-27 men, 17 of them fusiliers ; they were led by a captain, a role that Thomas Wilford took on in 1570. As the century progressed, the castle became more and more difficult to maintain. In 1568 the gun platforms were reported to be in ruins and the cost of repairs was estimated at £ 60; however, it is not clear whether the repairs were carried out. Tensions between England and Spain rose and in 1584 Queen Elizabeth I invested £ 171 in repairs to the castle because fear of an invasion of England was renewed. The Anglo-Spanish War broke out the following year and in 1588, the year of the Spanish Armada , a Jesuit priest named Father Darbysher and Roger Walton , a spy on the Spaniards' payroll, planned to hand the fort over to invading forces of French and Spanish soldiers even if their betrayal never bore fruit.

In 1593 there was another crisis with Spain and bronze guns that the English fleet needed were not available in sufficient numbers. Bronze guns were therefore collected from the forts on the English south coast, including Camber Castle. The number of guns in the castle remained about the same, but the large bronze field snakes and the smaller cannons were removed and replaced by smaller, iron field snakes, "sakers" and "minions". In 1594 another report to the Queen stated that £ 95 would be needed for repairs to the fortifications.

17th to 19th century

Closure and English Civil War

At the beginning of the 17th century, some changes were made to Camber Castle. In 1610 Peter Temple was appointed captain of the castle and between 1610 and 1614 the garrison was reduced to 14 soldiers, four of whom were fusiliers. The reason was either an attempt to save costs or to change the gun types on the castle. The northern and southern bastions were filled in around 1613 and 1615 and formed fixed gun platforms. A wall of earth called The Rampire was raised against the south corner of the castle. These fixed platforms cost housing less of which a smaller garrison needed, but they were cheaper to maintain. Longbows were no longer needed for the craft of war, as archery declined in England; they were replaced by arquebuses and muskets , 46 of which were stored in the castle in 1614.

Sir John Temple became captain in 1615 and was replaced by Robert Bacon in 1618 . The fortress was now both outdated and too far from the retreating sea to be of any military use. In 1623 it was proposed to close the castle and King Charles I was informed of the dilapidated condition of the fortress, which at that time was demonstrably already about 3 km away from the sea. The towns in the area campaigned for the castle to continue to be used, but Charles I ordered its destruction in 1636. The garrison, led by Captain Thomas Porter , left the castle the following year, followed by the artillery.

When the English Civil War broke out between supporters of Charles I and those of Parliament in 1642, Camber Castle was not yet completely closed and served as a royal ammunition depot. The citizens of Rye sided with the parliamentarians, who agreed that the weapons and ammunition should be removed from the castle and brought into town for safekeeping. The parliamentarians worried that the castle would be taken by the royalists and so continued the dismantling of the castle the following year: the roofs were covered, the loopholes closed and the living quarters destroyed. Therefore, Camber Castle was not used by the royalists in the second English civil war in 1648, even if many other coastal fortresses along the English south coast were taken by them.

In ruins

After the Stuart restoration by Charles II in 1660, a report to the king described the castle as a ruin. Increasing numbers of visitors came to see the castle in the 18th and 19th centuries; the northeast corner became a popular picnic spot. In 1785, historian Francis Grose attributed the fort's demise to changes in local ports and the greatness of the Royal Navy in protecting the coast, observing that the castle's architecture “clearly reflects the low level of military architecture” in 16th century England show.

In response to the threat posed by France during the Coalition Wars, Lieutenant Colonel John Brown examined the castle in 1804 to see if the central donjon could be converted into a Martello tower , a kind of circular gun turret that was common at the time could. His proposal was not carried out, even if the defenses of the surrounding coastline were significantly improved by the government. The painter William Turner visited the castle between 1805 and 1807 in the middle of the work and later depicted it in landscape paintings and sketches of the area.

20th and 21st centuries

At the beginning of the 20th century, Camber Castle and the surrounding farmland remained in private hands and were open to the public. In 1931 a proposal was made to convert the donjon into a clubhouse for the local golf club, but the project was abandoned and the clubhouse was instead built on the nearby Castle Farm . A team of investigators from the Victoria County History Project visited the castle in 1935 and prepared an initial, albeit crude, historical analysis and report of the fort, which was published two years later.

In the 1940s, most of the remains of the castle were covered with rubble, along the beaten track that visitors had created over the years. During World War II , the castle was used by the British Army , possibly as an advance warning post equipped with anti-aircraft searchlights . In an area immediately north of the castle, the starfish and navy mockups were created to distract the incoming German bombers from the town of Rye. Trenches have been dug in the northern bastion and military training is believed to have taken place around the outskirts of the castle.

In the post-war years, the archaeological interest in the castle grew. From 1951, the Ministry of Works carried out a long-term research project on device forts ; the section on Camber Castle was written by Martin Biddle and finally published in 1982. Biddle conducted archaeological research on the castle grounds in 1962 and the following year the ruins were closed to the public to allow for more extensive archaeological excavation by the Ministry. These were initially by Martin Biddle and Allen Cork with the support of local school children and young offenders from the correctional in Dover performed.

The state adopted the directive on Camber Castle in 1967 and the following year the government began the slow process of restoring the castle with the aim of reopening it to the public; their efforts were mainly directed to the protection of the brick inner walls and the wall cores. Further excavations followed in the 1970s and early 1980s.

In 1977 the Department of National Heritage bought the castle from the private owners. The government organization English Heritage took over the management of the castle in 1984 and in 1993 a project was started to reopen the castle to the public. This included a final summary of the archaeological work of the past decades. The castle was finally reopened to the public in 1994. Since 2015, the castle has been open to visitors as part of guided tours of the Rye Harbor Nature Reserve . The property is listed as a historical building of the first degree.

Architecture and landscape

landscape

Camber Castle is now on Brede Level , a wide reclaimed plain between the modern towns of Rye and Winchelsea, about 1.5 km from the coast. The surrounding pastureland is flat, just above sea level and is characterized by numerous ranges of hills that have been formed by the retreating sea over the centuries. To the east of the fortress is Castle Water , a large gravel construction from the 20th century, which is now flooded and forms a wetland for nature conservation .

A 1.8 meter high defensive earthwork runs around the south and east sides of the castle. Originally a stone wall was probably attached to it and it served to protect the castle from the sea, which was much closer at the time. The remains of an elevated dam, which once connected the isolated castle to the mainland, now lead a little bit to the southwest from the earthworks and then run into the sand. Traces of the holes that were dug at the beginning of the 17th century to obtain the filling material for the bastions are still preserved around the outer areas of the castle.

architecture

The three-story castle itself has seen little change since its completion in 1544; it contains elements of all three construction phases from 1512–1514, 1539–1540 and 1543–1544. Today it no longer has a roof, but still rises to 18 meters and covers an area of 3000 m², almost as much as Deal Castle, the largest coastal fortress in Kent . The first tower on the site was built from fine-grained yellow sandstone , the later extensions from both yellow and gray sandstone. The finer details are made of stone imported from Caen in Normandy . Iron stone (sandstone with iron ore deposits), siltstone and brown sandstone rubble and rubble were used for the wall cores. Some of this material comes from the local cliffs.

The castle could be entered through the entrance bastion. The core of this building was erected in the second construction phase and was initially a square, one-story construction with a floor area of 15 × 10.5 meters. It was later lengthened 9 meters to the front to form a round bastion. In the third construction phase, it was extended by another floor. Most of the inner walls were destroyed, but the first floor chambers were used for administration and possibly as living quarters for the second captain. On the first floor there was a suite of higher status rooms for the captain with large windows, open fireplaces and a private lavatory , but much of that floor was destroyed. A special, German tiled stove was probably built into the living quarters of Philip Chute, the castle's first captain. It was decorated with pictures of mercenaries and Protestant German military leaders. Only fragments of the furnace have survived to this day.

In the middle of the fortress was the donjon, which had arisen from the round tower from the first building phase; 6.7 meters of the original building walls were integrated into the new building. The original tower had ten loopholes built into the 3.05 meter thick walls at ground floor level; they were closed in the course of the second construction phase. The donjon originally had a parapet on the roof, which was initially flat, but was converted into a sloping roof in the third construction phase. The ground floor was made of brick and had a brick-clad well for the water supply. The keep had two open chimneys, but they were small and not intended for cooking - in fact, the last version of the keep probably never served as living quarters. The windows on the 1st floor were added in the last phase of construction; rather than being loopholes, they had cross bars and shutters so that they could be easily secured in the event of an attack.

An underground, arched ring corridor, only 1.9 meters high, ran around the outside of the donjon and there were similar, covered radial corridors that led off into each of the bastions. These passages are destroyed today. A paved courtyard surrounded the donjon, separated it from the outer defensive structures and housed a fountain in the northwest corner. Underground passages led from the entrance bastion under the castle walls to the outside, either to enable the garrison to escape in an emergency or to attack siege troops.

The outside of the castle was protected by an octagonal wall that connected the four “agitator towers” and the bastions that formed the outer defenses of the castle. This wall was originally built in the second construction phase, but was supplemented in the last construction phase by an additional 2.4 meter thick external cladding. It was originally provided with loopholes along each section and with parapets. A two-story gallery, which provided relatively spacious living quarters for the garrison, ran around the inside of the wall. Today only the ground floor of this gallery remains. The gallery was lit through windows facing the courtyard. The "rampire" earthwork, which was raised in the early 17th century, runs through the southern and southeastern portions of the defenses, where the loopholes were bricked in when the earth was poured along the inside of the castle.

The four “stirrer towers” are two stories high, have an inner surface of 6 × 6.2 meters and 0.8 meter thick walls, flat at the front and curved at the back. Gun platforms were originally attached to them and they had loopholes on the inside of the fortress from which the occupiers could fire into the castle courtyard if necessary. The bastions, which were built around the outside of the towers in the third construction phase, are 19 meters wide on the inside, extend from their respective “stirrer towers” 12 meters to the outside and have walls 3.6 meters thick. Most of the bastions had a single internal gun room with a sturdy gun platform above, only the western bastion served as a kitchen and its interior was equipped with two round ovens and cooking facilities. The bastions were connected by a wall and parapets, which no longer exist today. The southern "Rührerturm" and its bastion are partially buried today due to the filling of the "Rampire" earthworks.

literature

- Martin Biddle , Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001, ISBN 0-904220-23-0 ( digitized ).

Individual references and comments

- ↑ a b c d e Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 1.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 4-5, 7-8, 333.

- ^ A b c Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 21.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 11, 21.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 333.

- ^ A b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 11.

- ↑ a b c d It is difficult to compare costs and prices from the 16th century with those of modern times. £ 1309 from 1512 can equate to between £ 863,000 and £ 355 million in 2013, depending on the price comparison used, 5660 from 1539 between £ 3.33 million and £ 1.08 billion and £ 10,000 from 1542 between £ 5.27m and £ 1.73bn The repair cost of £ 171 out of 1584 could be between £ 44,400 and £ 11.9m in 2013. As an example, the total expenditure for all coastal fortresses in England between 1539 and 1547 was £ 376,500, with St Mawes e.g. B. £ 5018 and Sandgate £ 5584.

- ↑ a b c d e Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 12.

- ^ A b c d Lawrence H. Officer, Samuel H. Williamson: Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present . MeasuringWorth. 2014. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 1, 9, 21.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 336.

- ^ A b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford, 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp 21, 35, 52, 336th

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 22.

- ^ A b Bernard Lowry: Discovering Fortifications: From the Tudors to the Cold War . Shire Publications, Princes Risborough 2006. ISBN 978-0-747806-51-6 . P. 12.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 12, 22.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 11, 22, 89.

- ^ Steven A. Walton: State Building Through Building for the State: Foreign and Domestic Expertise in Tudor Fortifications in Osiris . Issue 25, No. 1 (2010). Pp. 68, 71.

- ^ A b c Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 25.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 28.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 32.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 55, 56, 344.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 31, 60, 337.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 31, 60.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 32, 34, 89.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford, 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p 31

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 333, 336, 344.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 333, 336.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 11, 22, 32, 89.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 33.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 32-33.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 12, 25.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 29, 89.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 344.

- ^ A b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 338.

- ^ A b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 40.

- ^ A b Peter Harrington: The Castles of Henry VIII . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2007. ISBN 978-1-472803-80-1 . P. 22

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 34.

- ^ Steven A. Walton: State Building Through Building for the State: Foreign and Domestic Expertise in Tudor Fortifications in Osiris . Issue 25, No. 1 (2010). Pp. 71, 84.

- ↑ JR Hale: Renaissance War Studies . Hambledon Press, London 1983. ISBN 0-907628-17-6 . P. 74.

- ^ A b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 26.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 26, 28.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford, 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p 1, 35th

- ^ A b c d Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 345.

- ↑ a b c d e Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 42.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 3, 42.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 46.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 44-46.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 33, 35.

- ^ A b c Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 39.

- ↑ Some historians are unsure of Henry VIII's spending on forts like Camber Castle, e. BR Allen Brown. He said: "The whole thing was typically a waste of money."

- ^ R. Allen Brown: Castles From the Air . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989. ISBN 0-521329-32-9 . P. 71.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 35-36.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 121.

- ^ A b c d Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 35.

- ^ A b c d Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 39, 44.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 35, 345.

- ^ A b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 35, 37, 123.

- ↑ The date when the baations were backfilled cannot be determined from the documented sources, even if the archaeological finds together with the documentary sources prompted English Heritage to estimate the period 1613–1615 for this work.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 35, 37.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 40-41.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford, 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p 35, 41st

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 41.

- ^ A b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 133.

- ^ Francis Grose: The Antiquities of England and Wales . Volume 5. S. Hooper, London 1785. S. 190.

- ↑ a b c Eric Shanes: The Life and Masterwork of JMW Turner . Parkstone Press, New York 2008. ISBN 978-1-859956-81-6 . Pp. 162-163.

- ^ A b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 12-13.

- ^ A b c Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 13.

- ↑ Camber Castle . Heritage Gateway. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ↑ Camber Castle . Historic England. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d e f Artillery castle and associated earthworks at Camber . Historic England. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 14, 135.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 14.

- ^ A b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 16.

- ↑ Oliver Gillie: A flawed bastion against the Armada reopens: Camber Castle was preserved because the sea left it behind. Oliver Gillie reports . The Independent. April 2, 1994. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ↑ Camber Castle . English Heritage. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 1-2.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 9-10.

- ^ Castle Water . Wild Rye. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological and Historical Structural Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 10, 118.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 10.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 137.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 138.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 56, 60, 107.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 340-341.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 107, 340.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 117-118.

- ↑ a b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological and Historical Structural Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 51.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 111.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford, 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p 51, the 112th

- ^ A b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 113.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 60, 115.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 116.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 156.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 100.

- ^ A b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 100-102.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 121-124.

- ^ A b Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 75, 77, 105-106.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 89-90.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , pp. 89-91, 341.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 90.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 75.

Web links

Coordinates: 50 ° 55 ′ 59 ″ N , 0 ° 43 ′ 56.9 ″ E