The Pale Rider

The Schimmelreiter is a novella by Theodor Storm from the literary era of realism . The work published in April 1888 is Storm's best-known short story and is one of his late works.

The novella, at the center of which is the fictional dikemaster Hauke Haien, is based on a legend that Storm dealt with for decades. However, he did not begin to write the novella until July 1886 and finished his work on it in February 1888, a few months before his death. The novella first appeared in April 1888 in the magazine Deutsche Rundschau , Vol. 55.

content

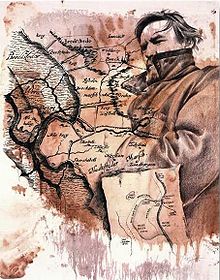

The novella Der Schimmelreiter is about the life story of Hauke Haien, which the schoolmaster of a village tells a rider in an inn. The dykes in North Friesland, the setting for the story, play an important role in Hauke's life. In the end, Hauke dies a tragic death with his wife and child.

Hauke Haien, the son of a surveyor and smallholder, prefers to deal with his father's work instead of meeting people of the same age. He watches his father and helps him measure and calculate pieces of land. He learns with the help of a Dutch Grammar Dutch , a Dutch edition of Euclid be able to read works that has the Father. He seems to be fascinated by the sea and the dikes. He often sits on the dike until late at night and watches the waves crash against the dam. He is thinking about how to improve protection against storm surges by making the dikes flatter towards the sea.

When the local dikemaster Tede Volkerts dismisses one of his servants , Hauke applies for the position and is accepted. But even here he helps the dikemaker more with arithmetic and planning than in the stables, which the dikemaker likes a lot, but makes him unpopular with Ole Peters, the foreman. Since Hauke can also arouse the interest of Elke, the daughter of the dikemaster, the conflict between Hauke Haien and Ole Peters intensifies.

At the North Frisian Winter Festival, Hauke wins the Boßeln and thus experiences first social recognition. Then he decides to have Elke made a ring and to propose to her at a relative's wedding. But Elke refuses for the time being, because she wants to wait until the father gives up his office. The plan is that Hauke, who now leads the office unofficially, should then apply as his successor through the wedding that was announced at the right time.

Within a short time, Hauke and Elke's fathers died. Hauke inherits his father's house and land. When it comes to reassigning the position of dikemaster, the conflict between Hauke and Ole germinates again. Traditionally, only those who own enough land can become dikers. This does not apply to Knecht Hauke, which is why one of the older dyke representatives should be promoted. Opposite the dikemaster who assigned the place of the local reeve to, Elke, however, took the floor and said that she was already with Hauke engaged and through a wedding Hauke will get the land of her father and that enough have land. This is how Hauke becomes Deichgraf.

Their dikemaster appears eerie to the villagers through his horse: a noble-looking white horse that , sick and depraved, he bought and nursed from a dodgy traveler. The mold, the residents mutually confirm, is said to be the revived horse skeleton from the abandoned Hallig Jeverssand, which disappeared when the mold was bought. Often the animal is associated with the devil and even referred to as the devil himself.

Hauke is now putting the new shape of the dike into practice, which he planned as a child. Some people are against it. But Hauke prevailed with the approval of the dichgrave. In front of a part of the old dike he has a new one built, a new Koog is created and thus more arable land for the farmers. When the workers want to bury a dog, as it is an old custom to build something “living” into the dike, he saves it, and so many see a curse on this dike. The fact that Hauke Haien already owns large pieces of land in the new Koog, partly through planning, partly by chance, and therefore benefits greatly from the construction of the dykes himself, is also met with discontent.

Day in, day out, he observes his dike by riding down it with his white horse. The new dike can withstand the storms, but the old dike, which continues to run to the right and left of the new Kooges and represents the foremost front to the sea, seems dilapidated and dug through by mice. In view of the appeasement by Ole Peters and the already grumbling workers, Hauke does not carry out any extensive construction work on the dike, but confines himself to patchwork with great remorse. Years later, when a storm flood of the century broke in and the old dike threatened to collapse, they wanted to break through the new dyke constructed by Hauke by order of the authorized representative, Ole Peters, who hoped that the power of the water would be in the new, uninhabited one Pour Koog and thus the old dike will be saved. Hauke confronts the workers shortly before the breakthrough and prevents the completion of this work, shortly afterwards the old dike finally breaks. When Elke and her daughter Wienke, who is mentally handicapped, drove out towards the dike that night out of fear for Hauke, he had to watch as the masses of water shooting through the dyke into the old Koog buried woman and child among themselves. In his desperation he throws himself and his horse into the raging waters that flood the land and cries: “Lord God, take me; spare the others! "

This ends the schoolmaster's story. He indicates that others would tell the story differently. At the time, all the inhabitants of the village were convinced that the horse skeleton was back on the Hallig after Hauke and his horse's death. He also mentions that the new dyke built by Hauke Haien can still withstand the floods, although the story told is said to have happened almost a hundred years ago.

Genus and form

Generic question - criteria for amendments

Theodor Storm himself subtitled his Schimmelreiter as a novella . This can also be proven by a few rudimentary criteria. The frame construction typical of the novel is noticeable right from the start, which Storm artistically doubles up on the narrators “newspaper reader”, “traveler” and “schoolmaster”. The entire structure confirms Storm's own claim that the novella should correspond to the drama. Whether the falcon - according to Heyse's common falcon theory - is the mold here or rather the dike is controversial. It is clear that the core of the conflict in the novella can neither be limited to the topic of the culture-creating struggle of man against nature nor to the problem of insurmountable superstitions in the actually enlightened modern age.

The narrative is assigned to literary realism . According to Christian Begemann, the Schimmelreiter not only shows how interpretations of reality that have apparently become obsolete can serve to question their self-confidence in the midst of an epoch that believes in science. Similar to Fontane's ballad Die Brück 'am Tay (1880), Begemann sees the Schimmelreiter as a return of the mythical in a seemingly rationalized world that demonstrates its endangerment, instability and literal bottomlessness. In the case of the Schimmelreiter, this is taken to extremes when Hauke Haien, as a technology-minded scout, becomes a revenant himself .

From the reflective treatment of the legendary material, Storm specifically stimulates the genre question here - in a very modern way, since it was a constitutive part of the genre, not only since Goethe's definition of the novella as an "unheard-of, occurrence" to show a clear reference to reality.

Structure of the novella

The work is structured in three narrative levels. First, a narrator reports on how he once heard about a story. Then a frame narration is constructed. In this context, a traveler tells how he makes his way to the city on horseback in storms and rain from a visit to relatives. During the ride on the dike , he perceives a dark figure on a white horse that passes by. It is the gray rider who throws himself into a hole with his horse . The traveler finally sees the lights of an inn in the distance, stops there and reports on his experience. The guests present are disturbed by his words, and an old schoolmaster begins - as an internal narrator and on the third level - to tell the story of Hauke Haien. The internal action is interrupted again at certain points to increase the tension by the internal frame, which, in contrast to the external, also closes again.

The narrative structure

The three-stage narrative structure in the Schimmelreiter offers both insights into the credibility of the novella and the associated interpretative approaches. The story is started by a first narrator who has neither a name nor certain character traits. He tells from memory of a story he found in a magazine. This transcript is also a memory - but from another narrator. This narrator is a (also) nameless dike traveler who sees the “Schimmelreiter” and lets the third and final narrator tell him the story. This last narrator is a schoolmaster who both knows about the legend of the white horse rider and has compiled the "real" facts related to it. But even its facts seem to be based for the most part on oral tradition, whereby the credibility leaves a lot to be desired and the story must be understood more as a "story about the storytelling" than a testimony about real events. Nonetheless, the choice of three male narrators is a sign that greater emphasis is being placed on the confirmed, written narrative and that the “female voice” is being neglected in favor of this fact-based male perspective. This “feminine connotation” voice is “[the] only hinted superstitious story”, which creates a complex narrative structure. The masculine narrative style represents an enlightened view in which progress and science play an important role. But the schoolmaster's enlightened attitude is also inadequate, because he cannot completely deny the existence of the Schimmelreiter for himself, as he is only brought to his narrative by mentioning the legendary figure. The great value that the schoolmaster places on knowledge and education about emotions (and in case of doubt also about money) creates a sympathy and similarity to Hauke Haien. Even more, Hauke could be seen as the ideal image of the schoolmaster, since Hauke is not only described with better physical characteristics, but was also able to assert his ambitions.

interpretation

Hauke's character

Hauke Haien's character is ambivalent. On the one hand he is intelligent, determined and mostly loving, on the other hand he can be aggressive, ruthless, indifferent and hateful.

Hauke is withdrawn from a young age and spends the days alone on the dike. One of his pastimes is shooting sandpipers with stones. This senseless pastime not only reveals Hauke's aggressiveness, but also his need to demonstrate superiority. This behavior culminates in the fact that he strangles old Trin 'Jans' angora cat in a rage. He shows a "destructive nature behavior" and he has the need to prove himself to be the stronger. According to Jost Hermand , Hauke develops into what he really is: "A closed and lonely violent nature". In order to reduce his aggression, Hauke throws himself into work from now on and his work efforts also have a combative character: he wants to dominate nature through the new dike and thus demonstrate his superiority to himself and his fellow men. Because of his rational, idiosyncratic and self-confident manner, he is unpopular with the villagers. Hauke sees only himself called to the dikemaster and regards the others as a threat:

“A series of faces passed before his inward gaze, and they all looked at him with evil eyes; Then he felt a grudge against these people: he stretched out his arms as if he were reaching for them, because they wanted to urge him from the office to which he was the only one called. - And the thoughts did not leave him; they were there again and again, and so in his young heart grew not only honesty and love but also ambition and hatred. But he locked these two deep inside himself; even Elke doesn't know anything about it. "

The relationship between Hauke and the villagers is made even worse by Hauke's purchase of the white horse and the associated superstitious fears of his fellow men. They encounter Hauke more and more with suspicion, fear and defiance, which in turn makes Hauke harder and more stubborn, especially with regard to the dike work. Tragically, he does not defy the other villagers any more than the flood disaster could have prevented: After proposing a thorough repair and reinforcement in the style of the new dike due to damage to the old dike, he encountered broad opposition - especially from Ole Peters. During a further inspection of the dike in question, he allows himself to be guided by these objections in his reassessment and agrees to a minor repair measure. At this point, however, the dike later breaks.

Hauke's wife Elke and his daughter Wienke know him as a nice, caring and loving man. But he is not exclusively hostile to the villagers either: He helps his servant Iven up and asks about his condition after he was knocked over by Hauke's white horse. He is also loving and nurturing his gray horse, which Hauke bought out of pity. Hauke also defies the superstition of the villagers and thus saves the life of a dog.

Animals as companions of the devil

The animals in Storm's novella play an important role. Nature acts as evil and the animals serve as symbols. The white angora cat of old Trin 'Jans is the first sign of the demonic: He envies Hauke his prey, which is why he strangles the cat and commits his first offense against nature. Then the witch-like Trin 'Jans curses him. Rats and otters, which snatch the old woman's ducks, are known to be devil animals that damage livestock and surround Hauke even in his youth. Once more the demonic re-enters Hauke's life through the purchase of the white horse. The initially gaunt animal with the fiery eyes is scary to everyone in the village, except Hauke, because he is the only one who can ride the untamed white horse. His second offense against nature is the unredeemed dike sacrifice, which at the same time violates the usual custom of the villagers. Hauke wrests nature's rightful sacrifice, which he later has to atone for with his own life. Another mistake Hauke makes is taking the Trin 'Jans into his home because they bring the fur of their white Angora cat with them. The animals, the refused dog sacrifice and Trin 'Jans are all in his immediate vicinity and represent emblems of the devil. The white color of the male, gray horse and black-headed gull are also striking. Since black animals would have been too obvious in the story, the white color stands as a symbol of calamity. All of Hauke's animal companions are not completely tamed and therefore put Hauke's existence in a threatening light.

The mold comes from a legend from Germanic mythology, in which the animal was once sacred and was associated with Frô (Freyr) and Wodan (Odin). The god Fro owned prophetic white horses that served as a consultant and Wodan rode a white horse to hunt. Only later did the animal have a pagan negative connotation due to Christianization and associated with the wild hunter, Hel, the ruler of the underworld or the devil himself. With the purchase of this demonic being, also acquired from a strange and strangely devilishly laughing man, Hauke attracts the attention of the superstitious village community. Holander writes: “Schimmel - Teufel - Tod, that is the superstitious association Storm builds on in order to give his gray horse the necessary ghostly traits. Based on this it is easy to let the rider himself appear in an aura of evil and ruin. "

backgrounds

Possible origin of the legend on the Vistula

Ghost stories from Schleswig-Holstein have fascinated Storm since his youth. He was inspired by this to write his own stories and planned to publish them one day in a collection entitled New Ghost Book . This publication did not occur during Storm's lifetime; the collection was first published in 1991. The Schimmelreiter is not included in this collection. In a letter to a friend, Storm writes that although this saga fits other stories due to its character, it unfortunately "does not belong to our fatherland " .

Storm writes in the introduction to his novella:

“What I intend to report was made known to me more than half a century ago in the house of my great-grandmother, old Mrs. Senator Feddersen, while I was sitting at her armchair, reading a magazine bound in blue cardboard; I can no longer remember whether from Leipzig or Pappe's Hamburg readings . "

In fact, in 1838 the Hamburger Pappe-Verlag published an edition containing a reprint of the Danzig steamboat from April 14, 1838. That reprint also included the story The Ghostly Rider. A travel adventure . The setting of this story, which shows striking parallels, is not on the North Sea , but on the Vistula . This would explain why Storm did not want to include his novella The Schimmelreiter in his collection of New Ghost Stories. The legend often attributed to the novella that the white horse rider can be seen on a white horse whenever there is danger on the dike, is not found in Storm, but only in the story of 1838.

The characters in the novella and their historical models

Details about the life of the dyke jury are not found in the story of The Güttlander dyke jury . Storm took up the motif of this story, but he created the multitude of characters and their different characteristics himself. He based his actors on people who actually existed.

The template for the personality of Hauke Haien, the main character in Der Schimmelreiter , was in many ways the loner Hans Momsen from Fahretoft in North Friesland (1735-1811), who was a farmer, mechanic and mathematician. As an autodidact , he achieved astonishing achievements. He knew how to make sea clocks , telescopes and also organs . The reference to the historical person Momsen is also clear in the fact that Storm mentions his name (written Hans Mommsen ) in his novella.

Storm's novella also reflects the ideas of the dike construction financier Jean Henri Desmercières , who works in North Friesland, with regard to new dike profiles. Desmercières is considered to be the builder of the Sophien-Magdalenen-Kooges , the Desmerciereskooges and the Elisabeth-Sophien-Kooges . The Iwersen-Schmidt family of dikers is another role model for the person of Hauke Haiens. The disabled daughter of the dikemaster Johann Iversen Schmidt (the Younger) (1844–1917) seems to be the model for Hauke's daughter Wienke in the novella.

The British historian Harold James compares Hauke Haien's pursuits and philosophy of life with that of Alfred Krupps .

Landscape background

The Hattstedtermarsch and the Hattstedter Neue Koog form the scenic background for the novella. The Große Wehle north of the Hattstedtermarsch, the former Schimmelreiterkrug inn in Sterdebüll and the Harmelfshallig are considered to be models for the settings of the novella. The dikemaster's homestead in the novella seems to be a copy of the dikeman's yard Johann Iwersen-Schmidt (1798–1875). Similarities can also be found in other people and things.

A report of the storm surge on October 7, 1756 with 600 deaths in the North Sea served Storm as a further inspiration.

The nature reserve Hauke-Haien-Koog in North Friesland is named after the main character of the novella .

Film adaptations

Production from 1934

Director: Hans Deppe and Curt Oertel

Actors: Mathias Wieman , Marianne Hoppe , Hans Deppe . Music by Winfried Zillig.

Production from 1977

Director: Alfred Weidenmann

Actors: Lina Carstens , Anita Ekström , Gert Fröbe , Werner Hinz , John Phillip Law , Vera Tschechowa , Richard Lauffen . The music was written by Hans-Martin Majewski .

This film differs partly from the book. Many scenes in the novella are not included in the film or are modified, for example the death of Tede Volkerts and Hauke's daughter Wienke. The film was shot in Ockholm, among others . The main motif of the exterior shots was the Ockholmer Peterswarf . As in the book and in reality, she is also the dikemaster's court in the film.

Production from 1984

Director: Klaus Gendries

Actors: Sylvester Groth , Hansjürgen Hürrig , Fred Düren and others

This television film was a co-production between the GDR and the People's Republic of Poland . The scenes set on the North Sea were filmed on the Baltic coast of the two countries. The film was shown for the first time on GDR television on December 26, 1984 and had its German premiere on September 7, 1985 in Husum .

Stage versions

The Pale Rider. Twenty-two scenes and an interlude after Theodor Storm. Music by Wilfried Hiller . Libretto by Andreas KW Meyer . World premiere in Kiel 1998.

The Pale Rider. Editing: John von Düffel . First performance in Hamburg 2008.

The Pale Rider. Directed by Christian Schmidt, music by Friedrich Bassarek; "Theater am Rand", Zollbrücke (Märkisch-Oderland); Premiere 2017

First edition

Theodor Storm: The Schimmelreiter. Novella. Paetel Berlin, 1888, 222 pp. (W./G.² 49) ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

Secondary literature

- Paul Barz : The real Schimmelreiter. The story of a landscape and its poet Theodor Storm. Hamburg 2000.

- Andreas Blödorn: Telling stories: Storm's “Schimmelreiter”. In: Der Deutschunterricht LVII.2 (2005), pp. 8-17.

- Gerd Eversberg : Space and time in Storm's novella "Der Schimmelreiter". In: Schriften der Theodor-Storm-Gesellschaft , 58, 2009, pp. 15–23.

- Gerd Eversberg: The real Schimmelreiter. This is how (he) Storm found his Hauke Haien. Heath 2010.

- Gerd Eversberg: (Ed.): The Schimmelreiter. Novella by Theodor Storm. Historical-critical edition. Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-503-15506-4 .

- Theodor Storm: The Schimmelreiter. An annotated reading edition. Edited and explained by Gerd Eversberg. With the etchings by Alexander Eckener . Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-503-15572-9 . The volume contains the historical background of the novella.

- Regina Fasold: Theodor Storm. Metzler Collection, Vol. 304. Stuttgart 1997, pp. 152-167.

- Reimer Kay Holander : The Schimmelreiter - Poetry and Reality. Commentary and documentation on the novella "Der Schimmelreiter" by Theodor Storm. New, improved and updated edition. Bredstedt 2003.

- Karl Ernst Laage: The original ending of Storm's "Schimmelreiter-Novelle". In: Euphorion , 73, 1979, pp. 451-457, and in Schriften der Theodor-Storm-Gesellschaft , 30, 1981, pp. 57-67.

- Karl Ernst Laage (Ed.): Theodor Storm. The Pale Rider. Text, genesis, sources, locations, recording and criticism. 13th revised edition. Heath 2009.

- Jean Lefebvre: nothing but ghosts? The functions of the dike rider in the framework of the "Schimmelreiter". In: Schriften der Theodor-Storm-Gesellschaft , 58, 2009, pp. 7–13.

- Martin Lowsky: Theodor Storm: The Schimmelreiter. King's Explanations and Materials (Vol. 192). Hollfeld 2008.

- Albert Meier: “How does a horse get to Jevershallig?” The subversion of realism in Theodor Storm's “Der Schimmelreiter”. In: Hans Krah, Claus-Michael Ort (ed.): World designs in literature and media. Fantastic realities - realistic imaginations. Festschrift for Marianne Wünsch. Kiel 2002, pp. 167-179.

- Christian Neumann: Another story about the Schimmelreiter. The subtext of Storm's dyke novella from a literary psychological perspective. In: Writings of the Theodor Storm Society , 56, 2007, pp. 129–148.

- Wolfgang Palaver : Hauke Haien - a scapegoat? Theodor Storms Schimmelreiter from the perspective of René Girard's theory . In: P. Tschuggnall (Hrsg.): Religion - Literature - Arts. Aspects of a comparison. Anif / Salzburg 1998, pp. 221-236.

- Irmgard Roebling : "Of human tragedy and wild natural secrets". The theme of nature and femininity in “Der Schimmelreiter”. In: Gerd Eversberg, David Jackson, Eckart Pastor (Hrsg.): Stormlektüren. Festschrift for Karl Ernst Laage on his 80th birthday . Würzburg 2000, pp. 183-214.

- Harro Segeberg: Theodor Storm's story “Der Schimmelreiter” as a criticism of time and utopia. In: Harro Segeberg: Literary technology pictures. Studies on the relationship between technology and literary history in the 19th and early 20th centuries . Tübingen 1987, pp. 55-106

- Malte Stein: dike history with dialectics. In: Malte Stein: “To kill one's loved one”. Literary psychological studies on gender and generation conflicts in Theodor Storm's narrative work . Berlin 2006, pp. 173-258.

Web links

- The Schimmelreiter in Project Gutenberg ( currently usually not available for users from Germany )

- The Schimmelreiter in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Björn Bühner: Figure lexicon for Der Schimmelreiter . In: Literature Lexicon online .

- The Schimmelreiter as a free audio book (unabridged). LibriVox

- Information on the author, work and other works by Storm from the Hamburger Bildungsserver

- 4 interpretations. ( Memento from February 12, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ) on the Storm Society website

Individual evidence

- ^ Digitized at archive.org .

- ^ Christian Begemann: Fantastic and Realism (Germany) . In: Markus May, Hans Richard Brittnacher (Ed.): Fantastic. An interdisciplinary manual . Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, pp. 100–108.

- ↑ Ulrich Kittstein: ... what about the Schimmelreiter? In: Ulrich Kittstein, Stefani Kugler (ed.): Poetic orders. On the narrative prose of German realism . Publishing house Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2007, p. 273.

- ↑ Ulrich Kittstein: ... what about the Schimmelreiter? In: Ulrich Kittstein, Stefani Kugler (ed.): Poetic orders. On the narrative prose of German realism . Publishing house Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2007, p. 280.

- ↑ Ulrich Kittstein: ... what about the Schimmelreiter? In: Ulrich Kittstein, Stefani Kugler (ed.): Poetic orders. On the narrative prose of German realism . Publishing house Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2007, p. 287.

- ↑ Winfried Freund : Theodor Storm. The Pale Rider. Splendor and misery of the citizen . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 1984. p. 68.

- ↑ Gerd Weinrich: Basics and thoughts on understanding narrative literature Theodor Storm Der Schimmelreiter . Diesertweg Verlag, 1988, p. 48

- ↑ Ulrich Kittstein: ... what about the Schimmelreiter? In: Ulrich Kittstein, Stefani Kugler (ed.): Poetic orders. On the narrative prose of German realism . Publishing house Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2007.

- ↑ Ingo Meyer: Under the spell of reality. Studies on the problem of German realism and its narrative-symbolic strategies . Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2009, pp. 428–432.

- ↑ Reimer Kay Holander: The Ghost Rider - poetry and reality . Nordfriisk Instituut, Bräist / Bredstedt 2003, p. 32 ff.

- ↑ Reimer Kay Holander: The Ghost Rider - poetry and reality . Nordfriisk Instituut, Bräist / Bredstedt 2003, p. 34.

- ^ Afterword in: Der Schimmelreiter , Hamburger Reading Booklet, Husum 2004, p. 102.

- ↑ Harold James: Krupp - German legend and global company . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62414-8 , p. 31

- ^ Gerd Eversberg: Theodor Storms "Schimmelreiter" - An exhibition in the Storm house. Husum catalogs 2. Boyens Buchverlag, Heide 2009

- ↑ Klaus Hildebrandt: Theodor Storm The Schimmelreiter . Oldenbourg Verlag, 1999, p. 100