The wolf boy

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| German title | The Wolf Boy / The Wild Child (GDR) |

| Original title | L'Enfant sauvage |

| Country of production | France |

| original language | French |

| Publishing year | 1970 |

| length | 81 minutes |

| Age rating | FSK 12 |

| Rod | |

| Director | François Truffaut |

| script | François Truffaut Jean Gruault |

| production |

Marcel Berbert for Les Films du Carrosse / Les Productions Artistes Associés |

| music |

Antonio Vivaldi (conducted by Antoine Duhamel ) |

| camera | Néstor Almendros |

| cut | Agnes Guillemot |

| occupation | |

| |

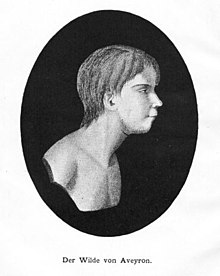

The wolf boy (original title: L'Enfant sauvage ) is a 1970 film by François Truffaut . The film is set in France around 1800. It shows the life story of the wolf boy Victor von Aveyron based on the documentary report Mémoire et rapport sur Victor l'Aveyron by the doctor Jean Itard . The Wolf Boy was shot in a documentary-like style in black and white and is one of the director's key works. Truffaut, who himself played the role of Dr. Itard plays, here combines two of his core themes: children and education. The film, shot on a small budget, received a number of awards and received an unexpectedly large response in France and the USA beyond cinéast circles. His subject matter hit the nerve of the times during the student unrest at that time and formed the basis for Truffaut's reputation as an “educational director”. In 2003 the film was included in the film canon created by the Federal Agency for Civic Education for work in schools.

action

In the summer of 1798, in the forest near Caune in the canton of St. Sernin in southern France, a woman discovers a little naked boy who moves like an animal through undergrowth and bushes and climbs trees. He is caught, tied up and brought to the village by men from the village. The news spreads quickly. The young Parisian doctor Dr. Itard reads a report about the boy in the newspaper. He is intrigued by the thought of examining the boy to determine the level of intelligence and the nature of thoughts of a child who grew up in total isolation without any human education . The boy is meanwhile being held captive in a barn and is used for general amusement in the village. After several attempts to escape, he was put in a prison cell in Rodez. The village doctor obtained permission from the Ministry of the Interior to take the boy to Paris to the national institute for the deaf and dumb.

After an investigation, Professor Pinel, the director of the institute, comes to the conclusion that there is nothing to distinguish the boy from other children in appearance. However, it has scars all over its body and does not react to sounds or visual stimuli, unless they have something to do with food intake. He does not recognize his reflection either. A noticeable scar on his neck suggests that Itard and Pinel concluded that the boy was abandoned by his parents when they were around three years old after they cut his throat, which he survived.

The boy is admitted to the institution. Dr. Itard takes over the care and begins to write down all the experiences he has with the boy. The boy takes on the role of a nerd among all the other deaf-mutes and he is regularly beaten by the other boys. One of the keepers shows it to groups of visitors from Paris for a fee. Dr. Itard does not believe in this kind of display and he regrets that the boy was torn out of his familiar surroundings, nature, simply out of sensation and curiosity. He fears that the boy will perish. Prof. Pinel thinks the boy is an idiot and wants to send him to the insane asylum in Bicêtre . He thinks he is inferior to all the other children in the institute. He even stands among the animals. Dr. Itard, on the other hand, considers the boy to be educable. It was only because of the external circumstances, the years of isolation. In his opinion, the child was abandoned not because he was demented, but because he was illegitimate. Itard takes the boy to Batignolles in the country to look after him with his housekeeper Mme. Guérin, for which she receives 150 francs a year.

After an initial reluctance, the boy gradually learns a few simple steps, such as eating his soup with a spoon or dressing himself. Apart from instinctive defense reactions, he shows no recognizable emotional impulses. On the neighboring Lemeri family farm, the boy occasionally plays with the family's son, who is a few years younger. He learns to drink milk from a bowl, set the table and express himself through gestures. Dr. Itard tries to introduce the boy to objects and language through play. The boy learns more quickly about games that have to do with food intake; when it comes to other objects, he is reluctant and appears listless and listless. Dr. Itard begins to reward the boy for learning success with food or drink.

The boy mostly does not react to speech, but shows a certain impulse with words that contain the sound "o". This is how the boy got his name Victor (in French the emphasis is on the long "o"). From now on, Dr. Itard and Mme. Guérin Victor to introduce onomatopoeic to the language. First they try water (French “eau”), later with milk (French “lait”). The only visible success is a "lait" beeped in a high voice, Victor's first utterance that does not consist of a grunt or squeak.

Dr. Itard does not know whether the few successes and advances are actual learning successes or whether the boy may only remember the things that lead him to success, the food intake. Itard now lets Victor do simpler things: drums, peas peeled off or wood sawed, which he clearly enjoys. Mme. Guérin discovers that Victor has a pronounced sense of order and that things that are elsewhere than the day before are put back in their original place. Victor now learns to assign objects such as hammer, book or comb to their abstract images, but he is not able to assign the objects to the written terms. Progress is sparse. Victor gets angry more and more often and he lashes out as soon as he fails to complete a task. However, if he can play casually, he is happy and exuberant.

After seven months, Prof. Pinel's opinion has now prevailed in Paris. Itard turns to the ministry, but initially has no success there. He now begins not only to reward Victor, but also to punish him for wrongdoing. It is particularly hard for Victor to be locked in the chamber. As a result of the punishment, Itard realizes that Victor is crying for the first time, which Itard records as another success. The successes are stagnating. Itard is discouraged and disappointed and he regrets having taken Victor into his home. A letter from the ministry arrives from Paris: Dr. Itard's academic work deserves recognition and government protection, and further progress is expected. Over time, Itard managed to get Victor to bring a wide variety of objects on demand. Victor even makes a chalk holder out of string and a bone of his own accord.

However, Itard is still unsure of the boy's motivation and he decides to punish the boy for no reason. Victor solves a simple task correctly, but is still locked in the chamber, whereupon he fights vehemently and cries. For Dr. Itard, this is proof that Victor has now developed a sense of justice. Nine months after Victor's arrival in Batignolles, Victor climbs out of the window and flees, but returns very soon. Outwardly, Victor lets himself be led upstairs indifferently. Itard decides to resume classes.

History of origin

First plans and work on the script

In 1964, Truffaut read in Le Monde about the book Les enfants sauvages - mythe et réalité by Lucien Malson , a professor of social psychology at the Center National de Pédagogie, who examined 52 cases of so-called wolf children who grew up in isolation, without any human contact . One such case was the case of Victor de Aveyron . Two reports from 1801 and 1806 are documented in Malson's book, in which the doctor Jean Itard describes his long- term attempts at teaching and bringing up a child who was taken to the wilderness. The first report was intended for the Acadèmie de Médicine and caused a sensation beyond the country's borders. The second report was addressed to the Ministry of the Interior and was linked to a request to continue the maintenance payment for Victor's foster mother Madame Guérin.

Truffaut was fascinated by the case and got ten copies of the book. He decided to make a film of the story. In the fall of 1964, Truffaut asked his co-writer for Jules and Jim (1962), Jean Gruault, to help with a script based on Jean Itard's notes. In January 1965 Gruault's first rough draft of a framework was ready. He obtained additional material on the subject, such as a work by Condillac from 1754 on dealing with the deaf, and he read specialist articles on autistic children. In November 1965 the script comprised 243 pages, which Truffaut annotated and returned to Gruault. By the end of 1966, the script had grown to just under 400 pages, which would have been equivalent to a three-hour film. Truffaut asked his friend Jacques Rivette for help. Rivette suggested in the fall of 1967 that the story should be focused entirely on the two main characters and that any distracting side strands should be radically shortened. Another nine months later, in the summer of 1968, the 151-page final version of the script was finally available.

Truffaut then met with a doctor who was performing experiments with the tuning fork on deaf children, as well as with other people who cared for deaf or autistic children. He even came across the case of a child whose behavior was very similar to that of Dr. Itard had described.

financing

In December 1966, Truffaut was busy with the preparations for his first and only English language film Fahrenheit 451 , he concluded a cooperation model between his own production company Les Films du Carrosse and the French subsidiary of United Artists Les Productions Artistes Associés . The aim was the joint production of the planned film The Bride Wore Black . As a result of this cooperation, the follow-up film Robbed Kisses was to be coproduced by Carosse and Artistes Associés .

In the fall of 1967 - neither of these two films was in theaters at the time - Truffaut concluded a further agreement with UA / Artists Associés for the production of the films The Secret of the False Bride and The Wolf Boy . United Artists co-produced both films in the hope of being able to compensate for the alleged loss of the second film with the expected profits from the first. The screenplay for Der Wolfsjunge was found to be "too documentary". In addition, Truffaut wanted to shoot in black and white , which in the late 1960s was also not considered to have an impact on the public. United Artists contributed two million francs to the project, ultimately with the aim of not losing Truffaut. UA took over the worldwide exploitation of the film.

In fact, The Secret of the False Bride turned into Truffaut's biggest financial failure to date, while The Wolf Boy , contrary to expectations, turned out to be a profit. But even before Der Wolfsjunge came into the cinemas, Truffaut decided to forego working with United Artist in the future due to hesitation.

Casting the roles

In order to find a suitable actor for the wolf boy, Truffaut and his assistant director Suzanne Schiffman interviewed and photographed around 2500 children in and around Marseille . Five of them were allowed to go to Paris for test shoots. At the beginning of March 1969, twelve-year-old Jean-Pierre Cargol was finally found. Cargol came from Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer , a small town near Marseille. Truffaut described the boy in a letter to his friend and colleague Helen Scott as a beautiful gypsy child with a very animal profile, which is ideal for the role due to his dark complexion and wiry figure.

In order to introduce the inexperienced boy to the difficult role, Truffaut developed a special technique: he worked with comparisons. He made Jean-Pierre look “like a dog”, move his head “like a horse” or look amazed like Harpo Marx with wide eyes . According to Truffaut, only outbursts of anger were a problem, because Jean-Pierre was a "very gentle, very happy and very balanced child."

For a long time Truffaut was undecided who should play the doctor Jean Itard. He thought of a television actor or a journalist, at least it shouldn't be a well-known movie actor. He was also looking for an unknown actor, but at some point he decided to take on the role himself. Truffaut had previously only appeared in small roles as an actor. This is one of the reasons why he kept his decision to himself until shortly before filming began and was then the first to initiate Suzanne Schiffman. He wrote to Gruault: “Please excuse me if I have hidden from you that I am playing the role of Dr. Play Itard myself, but I wanted to keep this a secret until the last moment. I hope my amateurish performance will not disappoint you. "

Truffaut saw this decision primarily as a pragmatic one. As a director, he had the task of leading and guiding the inexperienced actor Jean-Pierre Cargol. At the same time, the actor who played Dr. Itard was given the task of directing and teaching Victor the Wolf Boy. Truffaut combined both and thus avoided the intermediate level of a third person. Gruault agreed with him in this decision: "You see Itard almost exclusively in his professional activity, and it is very similar to that of the director."

In the two important supporting roles of Professor Pinel and Madame Guérin, Truffaut wanted them to be laid out as soberly as possible in order to focus the audience's emotions entirely on Victor. He hired two experienced theater actors: Jean Dasté, the director of the Comédie de Saint-Étienne and Françoise Seigner, a member of the Comédie-Française .

In order to save costs, Truffaut resorted to his own employees for other supporting roles, as in earlier films. For the Lemeri family, for example, he filled the production manager Claude Miller with his wife and baby as well as the son of his assistant. Truffaut's own eight- and ten-year-old daughters Eva and Laura got their first little film roles.

Filming and post production

Truffaut decided to shoot the film in black and white to underline the documentary claim. He chose Néstor Almendros for the camera work, and he was very impressed by his work on Éric Rohmer's film My Night at Maud . At that time, the Spaniard Almendros was already an internationally experienced and sought-after cameraman. Truffaut and Almendros looked at each other during the preparation time some thematically related films: Arthur Penn's The Miracle Worker on a blind and deaf and dumb girl, or Diary of a Country Priest by Robert Bresson . The time with Monika von Ingmar Bergman was on the program as well as some silent films . It was the first time they worked together and seven more films were to follow.

Truffaut chose Aubiat in the Puy-de-Dôme department in the French Massif Central as the filming location . There was a country house there that, with a few changes, became the house of Dr. Itard could be repurposed. Filming began on July 2, 1969 in the forest of Saint-Pardoux near Montluçon . In the first week only scenes were shot in the forest. The shooting went smoothly and made good progress. Truffaut found himself at home in his dual role as director and leading actor. Suzanne Schiffman replaced him as assistant director as soon as he was in front of the camera, she was also his lighting double during rehearsals. From the end of August, filming continued for a week in Paris at the Institute for the Deaf. After a total of 50 days of shooting, the team finally split up. Jean-Pierre Cargol received an 8 mm camera as a present from the crew.

Truffaut had decided to use contemporary music from the 18th century for Der Wolfsjunge and he chose two pieces by Vivaldi : The Concerto Pour Mandolin and The Concerto Pour Flautino . He asked the film composer Antoine Duhamel, with whom he had already worked on the two previous films, to record the pieces for him. As he recalled in an interview in 2007, Duhamel remembered working together on the two previous films as rather exhausting, as Truffaut was not very interested in post-production. However, Duhamel's work on Der Wolfsjunge was much easier due to the pre-selection of the music. Before the film was released in February 1970, Truffaut made another film with a table and bed , his fourth in two years.

Film analysis

Staging and dramaturgy

The film consists of three parts: the capture of Victor and his time in the village, the time in the deaf institute and the time with Dr. Itard in the country. The first two parts, which deal with the conflicts between civilization and nature (symbolized by the boy), cover about a third of the total film duration of around 80 minutes. The long months of learning thus take less than an hour in the film. Truffaut opted for this radical restriction, even though he already had a much more extensive draft script in order to strike a balance between the few successes and the actually much more numerous failures.

In the film, Dr. Itard new experiences and insights in the same ritual on paper at his desk and keeps them for posterity. Truffaut stuck to this model very closely and it ultimately determines the pace of the film. Truffaut's narrative voice, always quoting Itard's original documents, provides the transitions. Truffaut uses long settings and cuts very economically and with little effect. In this way, the successes and the setbacks are literally felt by the viewer.

Truffaut wanted Der Wolfsjunge , which he made in the form of a documentary, to be understood as an homage to classic cinema, and therefore shot in very fine-grain black and white, which was intended to be reminiscent of the early days of cinema and convey a semblance of objectivity. For some image transitions, especially for fading in and out by Victor, Truffaut used an iris diaphragm typical of the silent film of the 1920s , as he did in 1960 in Shoot at the Pianist and later in The Woman Next Door (1981). On the one hand, he shows the central role of Victor and, on the other hand, the isolation and confinement of Victor in his own world. In addition, the use of this stylistic device, which comes from the silent film , obviously fits in with a film that is, among other things, about learning to speak.

Use of music

An important aspect that illustrates the contrasts between the two worlds is the use of music. There is no background music in The Wolf Boy . The entire nine-minute opening sequence of the film is completely without music. The scenes that take place in the forest or in the village are only underlaid with sounds of nature and the twittering of birds. Music first played when Dr. Itard reads about the boy in the newspaper. The artificial music of the human world here contrasts with the natural music of the various kinds of noises in the forest.

Music is used in those scenes where something happens to Victor or where decisions are made about Victor. Truffaut only uses two pieces by Antonio Vivaldi : the concerto for mandolin and the concerto for flute .

The flute concerto is used in those scenes in which a progression of the plot or a further stage on Victor's path to becoming “human” can be recognized, but it also appears in those scenes in which the opposites of the two worlds are emphasized. The mandolin concerto, on the other hand, is always used when the action stagnates or setbacks are suffered.

When music starts playing for the first time, Dr. Itard wanted to take the boy in and to “educate” him, that is, to introduce him to human society. Truffaut uses the flute concert for this, which is also used in four similar scenes: the village doctor washes the boy's face in prison and exposes the people under the "wild" shell - the first step towards becoming physically human. Then later the two punishment scenes in which Victor cries for the first time and where he rebels against the unjust treatment. In both cases, Victor climbs a further step to "being human". Finally, the motif appears at the end of the film when Victor returns, after the boy has made a decision on his own for the first time. Scenes in which the contrast between Victor's free world and the artificial world of humans comes to light are also highlighted with the flute concert: Victor looks blankly in the mirror, he stands at the window and drinks water, he plays with a candle, and he plays in the garden at night when the moon is full, and Dr. Itard watched through the closed window.

The mandolin concert can be heard for the first time when Mme. Guérin Victor after his arrival at Dr. Itards cuts his nails and bathes him. All the games that Dr. Itard undertakes with Victor, as well as Itard's unpleasant trip to the ministry in Paris, are underlaid with this piece. The boy flees the doctor's house twice. The mandolin concert can be heard in both scenes. In the first case the doctor finds him on the tree in the garden, in the second time Victor finally returns some time later on his own initiative. In none of these scenes is there actually any progress in the learning process.

Themes and motifs

Differences between story and film

Truffaut put The Wolf Boy in the form of a documentary , but made adjustments for various reasons. He shortened the plot and, apart from the exposure , he masked out almost all elements that are not related to the relationship between the two main characters. In addition, he made adjustments for dramaturgical reasons. The reduction of reality to a small excerpt also serves to alienate the dramaturgy. This gives Truffaut the opportunity to set his own accents based on the original recordings and, above all, to incorporate autobiographical references .

The private life of Dr. Itard doesn't play a role in the film, other than knowing that he lives alone in a big house with his housekeeper. Not much is known about the historical Jean Itard's private life. He finished his medical studies in 1796 at the age of 25 and then turned to surgery . Soon after, he began studying hearing processes. In 1799 he worked at the National Institute for the Deaf, later the Imperial Deaf-Mute Institute in Paris, where he became chief physician in 1800. In 1821 he became a member of the Académie de Médicine. Due to his educational work with Victor as well as numerous treatises on language education and instruction for the deaf, Itard is regarded as a forerunner of deaf education and education for the mentally handicapped.

The film begins - as you can read in the opening credits - in the summer of 1798 with Victor's discovery in the forest and ends nine months after Dr. Itard Victor took in, that is, about one to two years later at the most, with Truffaut deliberately omitting further dates. The historic savage of Aveyron was first sighted and captured in the forest near Saint-Sernin-sur-Rance in the Aveyron department in the spring of 1797 . He was able to flee twice after a short time until he was brought to Rodez in January 1800. In Rodez, the boy was extensively observed and examined by the naturalist Bonnaterre. Those first three years are greatly shortened in the film and Bonnaterre is not mentioned at all.

The historical Victor is described as a "repulsive creature" who only wore a tattered shirt when it was picked up. In the film, however, the boy is naked. In addition, Truffaut explicitly cast the role of the boy with a “beautiful” boy - a dramaturgical necessity in order to steer the audience's sympathy.

In the institution for the deaf and dumb in Paris, to which the boy was transferred in 1799, the majority of doctors thought the boy was an incurable lunatic. Only Dr. Itard disagreed. In the film, the scientific controversy is entirely due to the two people Prof. Pinel and Dr. Itard reduced. Other doctors only appear as accessories.

Dr. Itard's 1801 report to the Acadèmie de Médicine reports on Victor's progress in the first year under Itard's care. The second report from 1806 to the Ministry of the Interior shows that after this point in time the development slowed down significantly and finally stagnated. Truffaut uses elements from both reports for the film, whereby it remains open whether the film ends before or after the first report is sent. The reports themselves are not mentioned in the film, it is only shown that Dr. Itard meticulously documented every detail.

Truffaut puts the positive developments in the foreground in contrast to the setbacks and brings together all the successes in these first nine months. Thus the film ends with the last hopeful moment in Victor's development. Truffaut changes individual elements for dramaturgical reasons. So he refrains from recording a documented episode in which Dr. Itard holds Victor upside down out of the fourth floor window as a punishment, and Victor cries for the first time. Instead, the rather harmless locking in the chamber is shown as a method of punishment in the film.

The Itard household actually consisted not only of the doctor and Madame Guérin, but initially also of their husband. Victor regularly set the table for four people. After Monsieur Guérin died, Victor was unable to grasp the changed situation on his own and continued to cover for four people. Victor was looked after by Madame Guérin until the end of his life and from the age of 18 he lived in an outbuilding of the institution for the deaf in Paris, where he died in 1828 at the age of 40. In these more than 20 years he made no further progress.

Contemporary history

With the 18th century, the Age of Enlightenment came to an end in France . The ideas of the Enlightenment were widespread among the people, but have already been called into question again in some cases. In 1755, Jean-Jacques Rousseau postulated in his treatise on the origin and foundations of inequality among human beings, the “ noble savage ” as the ideal of the natural man unspoiled by civilization. Seven years later, Rousseau presented his main work of educational theory with Émile or on education. Also in the middle of the 18th century, the Swedish scientist Carl von Linné coined the term homo ferus , which he described as a wild person who could not speak, who was unable to walk upright, and who behaved like an animal. When Victor was found at the end of the 18th century, intellectuals were still keen to pass on their ideas about "education". Dr. Itard took - in contrast to many of his colleagues - the view that it was possible to introduce a "savage" through education into civilization.

This shows an interesting parallel between the time around 1800, in which the film is set, and the year in which the film was released. The year 1970 was marked by ongoing student unrest and a broad social discussion about human interaction. There were heated discussions about bourgeois values and ideals, about exploitation and the balance of power. The educational system had been recognized as a major evil in the existing social system. Here, too, “education” and “upbringing” were recognized as the key to civilized coexistence, so that the film touched on a topic that was extremely topical at the time, despite the historical material.

Truffaut dealt with these questions neither in a scientific nor in an abstract way, but only let the wolf cub serve as a projection surface or a metaphor . Truffaut raised these questions and the viewer reflected on the real or supposed values of civilization based on the person of Victor, without expecting answers, since he had to know that Victor cannot give them. Truffaut thus evaded a historical classification, so that the film radiated topicality and authenticity despite the historical material . Even today, the questions raised here regarding generation conflicts, upbringing, school and society as well as social interaction, isolation or loneliness seem timeless.

Drawing of the figures and symbolism

Truffaut lets the adults act deliberately sober and emotionless in order to focus the audience on the boy's development without distraction or sympathy and to sensitize him to the hoped-for expressions of feeling Victor. Dr. Itard and Prof. Pinel dispute their dispute about Victor's condition and prospects exclusively on a scientific level. When exchanging the clearly differing opinions, no emotions whatsoever were discernible in either. The interest of Dr. Itards to Victor seems to be purely scientific at first. Only at the moment when Victor shows the first tentative emotions does Itard himself allow some, as he becomes impatient with the boy and finally wants to give up.

Finally, Mme. Guérin takes on her job with commitment, but also largely without emotion. Only in a few cases does she reveal her feelings: once when she accuses the doctor of overwhelming the boy, and then when Victor comes back at the end of the film and she takes him in her arms. This point in time, nine months after the start of the educational process, is also symbolic. Victor has now arrived in his new life, virtually (after a nine-month "pregnancy") he was born again, with Itard as father and Mme. Guérin as mother.

Truffaut had favorite subjects in his films that he kept coming back to. The subjects “books” and “reading” (as a synonym and basis for “education”) were part of it and he built them into many films. In Fahrenheit 451 , the film he was making when he began work on the script for The Wolf Boy , the theme was central. Many of the games that Dr. Itard thinks up for Victor are about letters and words. Itard keeps coming back to it, including in the two “punishment scenes”. In the second of these scenes, when Itard decides to unjustifiably punish Victor, he has Victor bring him a book and a key, two things Itard carefully selects from all previously used items. The combination of these two terms symbolically shows Truffaut's credo: books are the key to education and human development. The symbol of the key also runs through the entire film.

The obviously irreconcilable contrasts between the world of the boy and the world of humans are symbolized by Truffaut in a variety of ways. Right at the beginning, Victor's explicit nudity and the voluminous robes of the people in the village face each other. This is followed by the long shot of the institute's garden, which is fenced in by high walls and designed by human hands, as a symbol of the tamed nature in comparison to the free, wild nature outside in the forest.

Further symbols stand for these opposites: Mirrors appear several times in the film, most impressively in the scene, as Victor looks blankly into the mirror, in which Prof. Pinel and Dr. Mirror itard. A recurring symbol for the “artificial” world is the candle in contrast to the moon, which Victor, playing outside at night, looks at. Windows are or will be opened in some key scenes, symbolizing the balance between nature and culture. In two important scenes, however, windows are closed and thus symbolize the distance between the people standing behind them (once Prof. Pinel in conversation with Dr. Itard, once Dr. Itard alone) from nature.

The vital water, which is available “outside” in streams or as rain in abundance, is given “inside” by the doctor in small doses as a reward. After all, the intact Lemeri family, with whom Victor clearly feels at home, symbolizes the closeness to nature, while the Itard household, which is more abstractly composed of landlord, housekeeper and foundling, exudes a clear artificiality.

Autobiographical references

For Truffaut, a co-founder of the auteur theory , it was a matter of course to incorporate autobiographical references into all of his films. The Wolf Boy is dedicated to Jean-Pierre Léaud , whom Truffaut discovered in 1959 for his first work You Kissed and You Beat him, promoted him and made him a star. Truffaut became a kind of surrogate father for Léaud, he felt a certain degree of responsibility for him and was ultimately proud of his "work". Léaud owed his status and education to cinema.

Truffaut's own childhood was shattered. His mother never recognized him as a legitimate child, and he grew up with relatives, tolerated rather than loved, for most of his childhood. He often came into conflict with the law, and in the end he only learned from his own research that his supposed father, with whom he had a better relationship than his mother, was just his stepfather. At the age of 15, Truffaut was accepted by André Bazin , editor of the Cahiers du cinéma , and treated like a son. Bazin was devoted to you kissing and slapping him .

The relationship between Dr. Itard / Victor superficially reflects the Truffaut / Léaud relationship. However, some statements by Truffaut give rise to the assumption that the Bazin / Truffaut ratio was the model for the layout of the figures. Truffaut is so well-known that he prefers to make autobiographical references less in films based on his own models, i.e. the obviously autobiographical films, than rather hidden in his films based on someone else's model. In this way, he said, he felt more free to make statements about himself.

Truffaut was self-taught when it came to filmmaking . He understood this to mean that he only ever learned what seemed useful to him and what attracted him. This idea of only learning what one can need in further life therefore corresponds to his ideal upbringing, which he tries to pass on in The Wolf Boy . Dr. Itard is just as self-taught when it comes to upbringing as Truffaut is when it comes to filmmaking. Itard approaches the task scientifically and documents all of his results. He himself goes through a permanent learning process.

With this in mind, Truffaut's role in the film is very complex. He is known as Dr. Itard is Victor's surrogate father (and by dedication to Jean-Pierre Léaud), he is also Victor himself, who was led by Dr. Itard, who in turn stands for André Bazin, is brought up. In his role as a scientist he documents as accurately as possible and as a writer as vividly as possible, Victor's developmental steps. As a counterpart to this in real life, Truffaut is the scriptwriter who dramaturgically shortens and processes Itard's original, and finally the director who fills this script with life.

Reception and aftermath

Reactions to the premiere

Truffaut himself did not believe in the success of The Wolf Boy . He found the film too strict and sober for the general public. The premiere took place on February 26, 1970 in Paris.

Figaro praised the director beforehand :

"He does not play. He himself is the man who passes on the help that was given to him before. He recites the texts of Jean Itard and speaks the words that may have been so popular at the time. But at the same time Itard and Truffaut take Itard in. Perhaps never before has a historical role been interpreted so profoundly. "

After the premiere, the critics and the audience reacted very positively to the film. Le Monde wrote that in some kind of creatively inspired enthusiasm, Truffaut had successfully created an extremely noble work that was arguably the most confusing experience of his career. Truffaut is not only the cinéast who captures the movements of the heart and the poet who knows how to express nature and the fairytale of reality. By telling Dr. Itard himself plays, he forego an intermediary who directs the little boy. Truffaut is therefore at the same time father, teacher, doctor and researcher. Torn between enthusiasm and discouragement, between certainty and doubt, Itard would pursue his task. In the end, the film achieves all its meaning, its beauty. Because after an escape, Victor comes back to Itard. Although Victor can still neither speak nor understand, he is now able to express his emotions. His rebellion shows his understanding of how to differentiate between justice and injustice. When Itard says to him at the end: “You are no longer a savage if you are also not yet human”, then be sure that the advance to this point, to this exchange of familiarity, the experiences made were worth the experiment - just as much how it was worth the sufferings for Truffaut himself to rediscover his own childhood in his maturity by thinking about people with depth, lyricism and seriousness.

One week after the premiere, the culture magazine Télérama read about the film:

“'The Wolf Boy' is an unfinished film. One can be amazed that Truffaut created the most picturesque episodes from the memory of Dr. Itard left out, as did the rough episodes from puberty. However, it made the film stronger, denser, and truer. In the end it had to remain unfinished, like any upbringing. Dr. Itard had achieved his goal after a very surprising experience: in response to an injustice, the child bit the doctor. This act was ultimately the proof that the child had reached the height of the moral people. "

Effects of the film in France

Within a few weeks, 200,000 people saw the film in France and around 150 newspaper articles on the film appeared within six months. Truffaut received countless letters, mostly from students or teachers, all of which he answered personally. Truffaut became a sought-after interviewee and earned a reputation for being an educational director, which he thoroughly enjoyed.

The television journalist Pierre Dumayet invited Truffaut to his discussion program “L'Invité du dimanche”, where on October 29, 1969, he was given the opportunity to talk about many of the subjects of his heart, about upbringing, about childhood and about books, during prime time on French television to discuss. Dumayet opened the show with the words: "When you come out of this film, you are proud to be able to read." This is followed by other television appearances and a one-hour television documentary on the occasion of Truffaut's 10th anniversary as a director, some of which was shot in Aubiat .

The newspaper Le Nouvel Observateur writes in a detailed article about Truffaut: “Has the young wolf of the Nouvelle Vague now at thirty-eight become an unassailable director? No: Rather, he has become a person among people. ”In an interview, Truffaut affirmed that his films were a criticism of the French way of bringing up children. This became clear to him on his travels. He was amazed when he realized that the happiness of the children has nothing to do with the financial situation of their parents or in their country. While in poor Turkey the child is sacred, in Japan, as he said, relationships between children and parents are lousy and shabby.

Truffaut was now more than ever a public figure. In June 1970 he was given the opportunity to host RTL's midday magazine for a week . In quick succession he took up various topics that are close to his heart, for example the arms trade and censorship on television. He wanted to break taboos and some of the ideas he introduced were rejected by those responsible. Truffaut saw himself as an uncompromising, so sovereign and lonely man, his previous reputation as a rather shy person was gone.

Truffaut continued to advocate children's rights throughout the 1970s . He supported various associations such as the Perce-Neige founded by Lino Ventura or the association for the promotion of deaf children . He also supported other schools and centers that looked after children with behavioral problems or mentally disabled children. Truffaut donated generous amounts of money to all these institutions and he represented the interests of the affected children in public as often as he could.

Reactions abroad

Truffaut spent a lot of time and energy accompanying his films abroad and promoting them there. For The Wolf Boy , he visited over a dozen countries in Europe, plus Japan , Israel and Persia . But Truffaut knew that the success of a film in the United States is crucial for a director's reputation. For the American market, he recorded his own interim texts in English, so that only the few dialogues had to be subtitled and the film was therefore also accessible to children.

On September 10, 1970, The Wolf Boy was shown at the opening of the eighth New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center . Truffaut himself presented his film and it became the undisputed star of the festival. The New Haven Register wrote: “ L'Enfant Sauvage received rousing applause at the opening , and the sight of Truffaut's fragile and shy figure in the Philharmonic Hall's box of honor was one of those memorable moments in the spotlight that filled the hall with magic until the Headlights extinguished again. "

The film was soon released in American cinemas. In a short time, the debate about The Wild Child , the American distribution title, left cineastes and conquered magazines, newspapers and universities. The New York Times published a two-page portrait of Truffaut, extensively recognizing his acting skills and merits as a director. In the university cities, the success of the film touching a social phenomenon is even more evident. Many universities include the film in their programs for lectures on education.

The wolf boy grossed around $ 210,000 in the United States. He has received numerous awards from associations of critics and writers and from church organizations. Truffaut became one of the favorite European directors of American intellectuals, alongside Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini , particularly through Der Wolfsjunge . In the eyes of some critics, Truffaut became "the new Renoir" due to the success of his three "smaller films", Stolen Kisses , The Wolf Boy and Table and Bed . The New York press chief of United Artists wrote to Truffaut soon after the premiere of The Wolf Boy that he was well on the way to stepping out of the niche of an elite culture in major American cities and reaching a wider educated audience.

Well-known American filmmakers congratulated him on his success, including Stanley Kubrick , David O. Selznick and Gene Wilder . Truffaut has been friends with Alfred Hitchcock since the famous interview in 1962. Hitchcock wrote to him: “I checked out L'Enfant sauvage and thought it was great. Please get me an autograph of the actor who plays the doctor. He is wonderful. I want this autograph for Alma Hitchcock. The tears stood in her eyes. "

The German premiere of Der Wolfsjunge took place on April 8, 1971, and in the same month it was shown in GDR cinemas. The DEFA synchronization, praised as "careful" by Wolf Donner , was used in both German states.

Truffaut and Cargol's experience as an actor

For the two main actors this was their first experience as an actor. Truffaut made the filming great fun and he only had positive experiences:

“An actor's gaze in front of the film camera is extremely fascinating because it reflects pleasure and frustration at the same time. Pleasure, as the feminine side that is in every man (and especially in every actor) is satisfied by his role as an object. And frustration, because there is always a more or less pronounced virile trait that wants to rebel against this being an object. "

Truffaut had this first leading role later followed by two more in his own films: 1973 in The American Night and 1978 in The Green Room , in this film, as a reminiscence of The Wolf Boy , he takes in a deaf-mute boy. However, Truffaut's greatest international success as an actor was to have in 1977 in a supporting role in Steven Spielberg's film Close Encounters of the Third Kind . The character of the French linguist Lacombe was clearly different from Truffaut's role as Dr. Itard inspired in The Wolf Boy .

Jean-Pierre Cargol shouldn't have a long film career. In a letter from May 1970 he promised to become the first “gypsy director”. But nothing came of it. There was only one more film appearance to follow for him: in 1974 he had a supporting role in Duel in Vaccares .

Awards

The wolf boy was not only unexpectedly well received by critics and audiences, he also won several awards as a result. At the sixth International Film Festival in Tehran , the film won the special jury award. In France, The Wolf Boy won the Prix Méliès for best film in 1971 . The prize was awarded by the Union of French Cinema Critics ( Association Française de la Critique de Cinéma ).

The Film Society of Lincoln Center selected The Wolf Boy as the opening film for the eighth New York Film Festival in September 1970 (no prizes are awarded at this festival). The National Board of Review , a highly respected New York organization of filmmakers and film scholars, named The Wolf Boy Best Foreign Film and François Truffaut Best Director in 1971.

At the Laurel Awards , the film came third in the category of Best Foreign Film . Finally, Nestor Almendros won the NSFC Award from the US National Society of Film Critics Awards for his camera work. In addition, the film won several other awards from critics and writers' associations as well as from church organizations.

Retrospective review

In the retrospective criticism, Der Wolfsjunge is seen mostly positively. The Lexicon of International Films writes : "A human and artistically impressive document of belief in a certain ability to develop in every human being."

The Metzler Filmlexikon writes: “Only in a suitable social environment, that is how the morality of L'enfant sauvage could be described, can the natural disposition of humans develop and unfold. The director who made Dr. Itard himself portrayed, through the role, as he later admitted, became aware of his own father role towards the actor Jean-Pierre Léaud: he dedicated this film to him. "

In their Truffaut biography, published in 1996, De Baecque and Toubiana come to the conclusion: “The educational vocation of Truffaut and his cinema has never been clearer than in“ L'Enfant sauvage ”, an equally optimistic and desperate work. An optimistic film in that it completely trusts learning about culture; desperate, however, because it is precisely this educational process that repeatedly exposes society as a hideout for child molesters and cowards. "

In 2003 the Federal Agency for Civic Education, in cooperation with numerous filmmakers, created a film canon with a total of 35 films from eight decades for work in schools. The Wolf Boy is one of five French-language films.

literature

- Antoine de Baecque, Serge Toubiana: François Truffaut - biography. Editions Gallimard, Paris 1996, German 2004, Egmont vgs Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, ISBN 3-8025-3417-4 .

- Julie F. Codell: Playing Doctor: Francois Truffaut's L'Enfant sauvage and the Auteur / Autobiographer as Impersonator . In: Biography, University of Hawai'i Press Series, Volume 29, Number 1, Winter 2006, pp. 101-122

- Georgiana Colvile: Children Being Filmed by Truffaut . French Review. 63.3 (1990), pp. 444-451

- Frieda Grafe: Alpha and Omega - François Truffaut's film The Wolf Boy . First published in: Süddeutsche Zeitung on May 24, 1971; in: Schriften, 3rd volume , Brinkmann & Bose Verlag, Berlin 2003. ISBN 3-922660-82-7 . Pp. 78-80.

- Friedrich Koch : The wild child. The story of a failed dressage. Europäische Verlagsanstalt, Hamburg 1997, page 133 ff. ISBN 978-3-434-50410-8 .

- Friedrich Koch: Victor von Aveyron, Kaspar Hauser and Nell. A movie viewing. In: Pedagogy No. 6/1995, pp. 54 ff.

- Dieter Krusche, Jürgen Labenski : Reclam's film guide. 7th edition, Reclam, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-15-010205-7 , pp. 184f.

- Lucien Malson (ed.): The wild children . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1972

- Burkhard Voiges: The wolf boy . In: Alfred Holighaus (Ed.): The film canon - 35 films that you must know . Series of publications by the Federal Agency for Civic Education Volume 448, Bertz + Fischer, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-86505-160-X .

- Birgitt Werner: The education of the savage from Aveyron. An experiment on the threshold of modernity . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-631-52207-X .

- Willi Winkler : The Films by François Truffaut . Heyne, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-453-86080-2 .

Footnotes and individual references

- ^ Dieter Krusche, Jürgen Labenski: Reclams film guide. 7th edition, Reclam, Stuttgart 1987, pp. 184f.

- ^ Letter of September 6, 1969, quoted in de Baecque / Toubiana , p. 425

- ↑ statement by Truffaut in TELERAMA , quoted in de Baecque / Toubiana , p 426

- ^ Letter from Truffaut to Gruault, August 1, 1969, quoted in Voiges, p. 171

- ^ Letter from Gruault to Truffaut, August 2, 1969, quoted in de Baecque / Toubiana , p. 426

- ↑ Benoit Basirico: Interview BO: Antoine Duhamel. In: Cinezik.fr. November 3, 2010, accessed June 11, 2019 (French).

- ^ Alain Pinon: Formation autour du film… L'Enfant Sauvage de François Truffaut. In: Pistes Pédagogogiques. 2004/2005, archived from the original on January 25, 2008 ; accessed on June 11, 2019 (French).

- ↑ See “Voiges”, p. 171 ff.

-

↑ On the symbolism in The Wolf Boy, see, among others: L'enfant sauvage de François Truffaut. In: Ciné-club de Caen. Retrieved June 11, 2019 (French). Pierre Rostaing: De "L'enfant sauvage" à l'enfant philosophe. In: ac-grenoble.fr. January 10, 2005, archived from the original on September 30, 2007 ; accessed on June 11, 2019 (French).

- ↑ See Winkler , p. 116.

- ↑ Quoted from Winkler , p. 119.

- ^ Claude Mauriac in Le Figaro Littéraire , February 23, 1970; Original: “La creation de Truffaut n'est pas celle d'un acteur, bien qu'il soit aussi bon que le meilleur comédien. Il ne joue pas. Il est lui-même tel qu'il le souhaite: un homme qui aide après avoir été aidé. Disant devant nous le texte même de jean Itard, ou proférant des mots qu'il aurait pu dire, il est à la fois Itard et Truffaut, il est appliqué, il est grave comme jamais peut-être aucun interprète d'un rôle historique ne le fut. "

- ^ Yvonne Baby, in Le Monde , February 27, 1970; Original: “Truffaut, dans un élan inspiré de création totale, fait (et réussi) la plus noble et, nous semble-t-il, la plus bouleversante expérience de sa carrière. Il n'est pas seulement le cinéaste qui saisit les mouvements du coeur, le poète qui sait rendre la nature et la réalité 'féeriques', mais, jouant Itard, renonçant à utiliser un intermédiaire pour diriger son interprète, le Gitan Jean-Pierre Cargol, il devient tout ensemble et, en plus, un père, un éducateur, un médecin, un chercheur. [...] Entre l'enthousiasme et le découragement, entre la certitude et le doute, Itard poursuit sa tâche, et, dans cette dernière période, le film - qui, on le regrette, va bientôt s'achever - prend toute sa signification, sa beauté. Car, après une fugue, Victor est revenu chez lui, et quoiqu'il ne puisse tout comprendre ni ne réussisse à parler, il est devenu capable d'exprimer son affectivité et a découvert dans la révolte, “le sens du juste et de l 'injuste “. “Tu n'es plus un sauvage si tu n'es pas encore un homme”, lui dira, en finale, Itard, et il est sûr que pour en arriver à ce stade d'acquis moral, à cet échange de tendresse, de confiance, l'expérience valait d'être tentée. Comme il valait la peine pour Truffaut de retrouver l'enfance à travers sa propre maturité, de s'interroger sur l'homme avec profondeur, lyrisme, gravité. ”

- ↑ Jean Collet, Télérama, March 7, 1970; Original: «L'Enfant Sauvage est un film inachevé. On peut s'étonner que Truffaut ait supprimé les épisodes les plus pittoresques du 'mémoire', du docteur Itard, ou même les plus croustillants, comme ceux de la puberté. Le film n‚en est que plus fort, plus serré, plus vrai. Inachevé, il doit l'être comme toute éducation. Son but pourtant est atteint après une expérience où le docteur Itard peut s'émerveiller enfin: en réponse à une injustice, l'enfant a mordu le docteur. [...] Oui, cette révolte était la preuve que l'enfant accédait à la hauteur de l'homme moral. "

- ↑ Pierre Dumayet in his program "L'Invité du dimanche" on October 29, 1969

- ↑ Le Nouvel Observateur , March 2, 1970, cited in de Baecque / Doubiana , p. 437

- ↑ Interview in Le Nouvel Observateur , March 2, 1970, quoted in de Baecque / Doubiana , p. 437

- ^ Perce-Neige. Fondation d'aide aux personnes handicapées, accessed on June 11, 2019 (French).

- ↑ See De Baecque / Doubiana , p. 674

- ^ Roger Ebert : The Wild Child. In: rogerebert.com. October 16, 1970, accessed June 11, 2019 .

- ^ New Haven Register , September 20, 1970, cited in de Baecque / Doubiana , p. 443

- ↑ After De Baecque / Doubiana , p 440

- ^ Letter from Hitchcock to Truffaut, quoted in de Baecque / Doubiana , p. 444

- ↑ according to Internet Movie Database : April 23, 1971

- ↑ Wolf Donner : The dressage for humans . In: Die Zeit of May 28, 1971.

- ↑ statement by Truffaut in TELERAMA , quoted in de Baecque / Toubiana , p 427

- ↑ See de Baecque / Doubiana , p. 427.

- ↑ a b See De Baecque / Doubiana , p. 441.

Web links

- The Wild Child in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- The Wild Child at Rotten Tomatoes (English)